Summary

Background

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory condition of the airways and patients sensitized to airborne fungi such as Aspergillus fumigatus have more severe asthma. Thickening of the bronchial subepithelial layer is a contributing factor to asthma severity for which no current treatment exists. Airway epithelium acts as an initial defence barrier to inhaled spores, orchestrating an inflammatory response and contributing to subepithelial fibrosis.

Objective

We aimed to analyse the production of pro‐fibrogenic factors by airway epithelium in response to A fumigatus, in order to propose novel anti‐fibrotic strategies for fungal‐induced asthma.

Methods

We assessed the induction of key pro‐fibrogenic factors, TGF‐β1, TGF‐β2, periostin and endothelin‐1, by human airway epithelial cells and in mice exposed to A fumigatus spores or secreted fungal factors.

Results

Aspergillus fumigatus specifically caused production of endothelin‐1 by epithelial cells in vitro but not any of the other pro‐fibrogenic factors assessed. A fumigatus also induced endothelin‐1 in murine lungs, associated with extensive inflammation and airway remodelling. Using a selective endothelin‐1 receptor antagonist, we demonstrated for the first time that endothelin‐1 drives many features of airway remodelling and inflammation elicited by A fumigatus.

Conclusion

Our findings are consistent with the hypothesis that elevated endothelin‐1 levels contribute to subepithelial thickening and highlight this factor as a possible therapeutic target for difficult‐to‐treat fungal‐induced asthma.

Keywords: airway epithelium, Aspergillus fumigatus, asthma, endothelin‐1, remodelling

1. INTRODUCTION

Asthma is a chronic respiratory condition affecting approximately 300 million people world‐wide, accounting for around a quarter of a million deaths annually.1 Asthma is characterized by two main pathophysiological features, airway inflammation and airway remodelling, which together contribute to symptoms such as breathlessness, wheeze and persistent cough. Remodelling of the airways is poorly characterized, despite evidence suggesting its occurrence may proceed or occur in parallel to inflammation in childhood asthma.2, 3 Airway remodelling describes denuding of the epithelium, subepithelial fibrosis with increased extracellular matrix deposition, extensive smooth muscle hypertrophy and goblet cell hyperplasia.4, 5 Such airway remodelling contributes to the severity of exacerbations to aeroallergens such as those from house dust mite, pollen, animal dander and fungi. At present, no available therapy specifically targets the airway remodelling aspect of asthma.

Epidemiological studies have shown that severe asthma with fungal sensitization (SAFs) is associated with a high incidence of allergy to airborne fungi including Aspergillus fumigatus (A fumigatus).6 It has been estimated that as many as 28% of people with asthma are hypersensitive to A fumigatus, but disease aetiology is unclear.7 A fumigatus spores can be found at high concentrations with the average adult inhaling several hundred per day.8 With a diameter of just 2‐3 μm, A fumigatus spores may disseminate throughout the airway reaching distal alveoli.8 In healthy individuals, inhaled spores are likely cleared by alveolar macrophages, but immunocompromised patients or those with reduced lung function are more prone to retain spores in their airway which may permit spore germination and prolonged host allergen exposure.9

Airway epithelium provides a physical barrier separating underlying tissue from the external environment and provides the first line of defence to inhaled A fumigatus spores. Through its pivotal role in recruiting innate immune cells,10 and mediating an adaptive immune response,11 airway epithelium is at the interface of host‐environment interactions and as such plays a significant role in regulating airway homeostasis.12, 13 Furthermore, signalling through an epithelial‐mesenchymal trophic unit (EMTU) may enable epithelial cells to regulate fibroblast behaviour in the subepithelial layer14 so governing the extent of repair following airway damage. Previous studies have shown that airway epithelial cells respond to germinating spores and hyphae of A fumigatus via production of a number of key cytokines including IL6, IL8, GM‐CSF and TNF‐α.15, 16 In addition, we and others have established that inhalation of components of A fumigatus in vivo elicits airway inflammatory and remodelling responses through release of secreted fungal products including allergens with protease activity.17, 18 However, it remains unclear whether A fumigatus spores and/or its components induce airway epithelium to produce pro‐fibrogenic growth factors, which may in turn contribute to airway remodelling and asthma severity.

Biopsies from asthmatic lungs show an up‐regulation of a number of pro‐fibrogenic factors including Transforming growth factor (TGF) β1 and β2, levels of which correlate with subepithelial fibrosis.19, 20 Periostin, a matricellular protein and promising asthma biomarker, is also up‐regulated in asthmatic airways and serum21, 22 and endothelin‐1 (ET‐1), an important contributor to organ fibrosis, is increased in exhaled breath condensate derived from people with asthma and in lavage fluid of atopic asthmatics.23, 24, 25 Furthermore, extensive evidence suggests a role for ET‐1 in remodelling and fibrosis of the airway associated with bronchiectasis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and scleroderma lung disease, suggesting that this growth factor may be central for driving lung fibrosis in multiple settings.26 These growth factors have been shown to elicit fibrogenic effects in cultured fibroblasts27, 28, 29 and contribute to airway remodelling events in vivo following exposure to aeroallergens such as house dust mite extract and ovalbumin.30, 31, 32 However, the major pro‐fibrogenic growth factors likely to contribute to A fumigatus‐induced airway remodelling have not yet been defined. The purpose of this study was to elucidate the growth factors produced following A fumigatus inhalation that drive subepithelial fibrosis in order to identify therapeutic targets.

2. METHODS

2.1. Aspergillus fumigatus culture

Aspergillus fumigatus strain Af293 was used, originally obtained from Manchester mycology reference centre (Wythenshawe, UK) and kindly gifted by P. Bowyer (University of Manchester). A fumigatus was cultured on Sabouraud dextrose agar (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK) at 37°C for 5 days. Spores were harvested with a vigorous PBS Tween (0.05% tween 20) wash and hyphae removed using sterilized lens cloth. For in vivo studies, spores were harvested as described with a minor modification of using 0.05% tween 80. Spores were then passed through 40 μm nylon mesh and centrifuged for 5 minutes at 10 000 g at 4°C twice. The concentration of spores was adjusted to 5 × 108 spores/mL, aliquoted and frozen. Culture filtrates were produced according to our previously described protocol.18 Briefly, Erlenmeyer flasks containing 500 mL Vogel's minimal media were inoculated with 500 × 106 spores/mL and cultured for 48 hours at 37°C at 320 rpm. Resultant cultures were filtered through J cloth and sterile filtered (0.2 μm). Filtrates were dialysed overnight, freeze‐dried and stored at −80°C. Freeze‐dried aliquots were reconstituted with sterile PBS, and total protein content was determined using the BCA protein assay before use (Thermo Scientific, Loughborough, UK).

2.2. Bronchial epithelial cell culture and exposure to A fumigatus

Human primary bronchial epithelial cells (BECs) were purchased from Promocell (Heidelberg, Germany) and Lonza (Basel, Switzerland). Cells were cultured in Bronchial Epithelial Cell Growth Media supplemented with BEGM BulletKit (Lonza) in 75‐cm2 flasks until they reached 80% confluence. For experiments, BECs were used between passages 2 and 3 and seeded at 15 × 103/cm2. Monolayers were exposed to 1 × 105 spores/mL for 12 and 24 hours or 1 μg/mL A fumigatus culture filtrate for 24 hours. At the end of the study, culture supernatants were collected and levels of TGF‐β1, ET‐1, periostin and TGF‐β2 determined using DuoSet® ELISA kits performed according to manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK). For cultures involving germinating spores, cell layers were collected for analysis of gene expression, whilst supernatants were filtered through a 0.22 μm filter for ELISA.

In some experiments, in order to assess the growth of A fumigatus in the presence of epithelial cells, cultures were stained for calcofluor‐white (Sigma‐Aldrich, Poole, UK) and time‐lapse imaging performed using the Nikon Eclipse TE2000E microscope at X20 using an ORCA‐ER CCD camera (Hamamatsu, Welwyn Garden City, UK).

2.3. Murine models of A fumigatus induced airway inflammation and remodelling

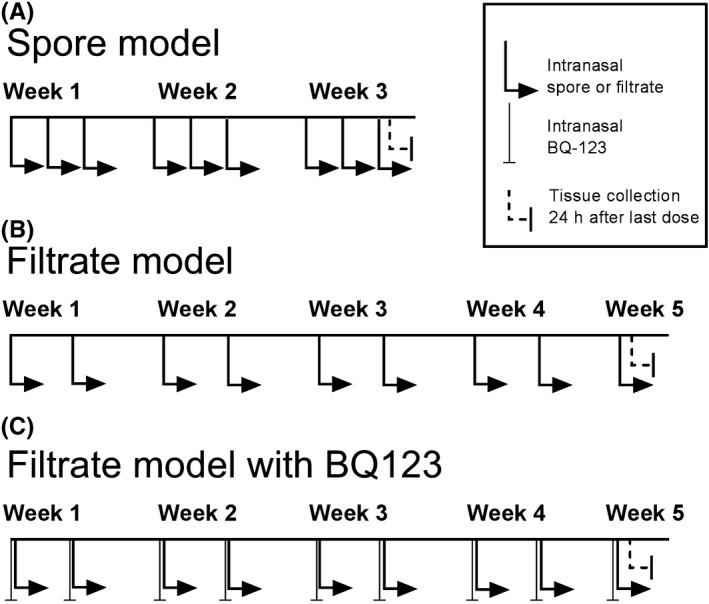

Male C57BL/6J mice, aged 8 weeks (Charles River Laboratories, Harlow, UK), were maintained under specific pathogen‐free conditions for the duration of the study with food and water available ad libitum. All procedures were performed in accordance with the UK Animal Scientific Procedures Act 1986 with local ethical committee approval. For the A fumigatus spore exposure model, mice were anesthetized with 2%‐3% isoflurane and 40 μL of 4 × 105 spores in PBS Tween 80 (0.05%) or PBS Tween 80 (0.05%) alone was administered intranasally (Figure 1A). Mice were dosed a total of nine times over three consecutive weeks following a previously published protocol.33 For the A fumigatus culture filtrate exposure model, mice were anesthetized with 2%‐3% isoflurane and 25 μL of the culture filtrate (containing 50 μg of protein) or PBS was administered intranasally (Figure 1B). Mice were dosed twice a week for 4 weeks followed by a final dose on week five following our previous protocol.18 In studies, involving ET‐1 receptor antagonist (BQ‐123; Sigma), 50 pmol of antagonist in 25 μL PBS or PBS alone was intranasally dosed 30 minutes prior to culture filtrate administration (Figure 1C). Twenty‐four hours after final A fumigatus exposure, animals were killed and samples including bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), serum and lung collected, processed and analysed as previously described.18 Cytokines and growth factors were assessed in BALF and lung homogenate and IgE in serum by ELISA (Data S1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the experimental design of the murine models of Aspergillus fumigatus exposure. A, Spore inhalation model involved mice receiving an intranasal dose of spores nine times over three consecutive weeks, and sample collection performed 24 h after final exposure. B, Culture filtrate model involved mice receiving an intranasal dose of culture filtrate nine times over five consecutive weeks with sample collection performed 24 h after final exposure. C, A separate group of mice also received an intranasal dose of BQ‐123, an ET‐1 receptor antagonist, 30 min prior to A fumigatus culture filtrate exposure

2.4. Real‐time PCR for growth factor gene expression

RNA was extracted from cell monolayers and frozen homogenized lung samples using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Crawley, UK). Reverse transcription was performed using TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagents (ThermoFisher Scientific). Using the SensiFAST SYBR No‐ROX Kit (Bioline, London, UK), qRT‐PCR reactions were performed in technical triplicate using forward and reverse primers for gene expression of ET‐1, TGF‐β1, TGF‐β2, periostin and normalized to GAPDH or RPL13 as housekeeping genes (Data S1).

2.5. Histology and immunofluorescence

The entire left lobe was fixed in buffered paraformaldehyde and wax embedded to permit direct comparison between experimental animals. Serial transverse 8 μm lung sections from the same region in each lung were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or Masson's trichrome. For analysis of subepithelial collagen thickness, at least five images of bronchioles within ×20 magnification field of view, from the same region of the lung were captured for each animal. For immunofluorescence, sections were permeabilized and then incubated with primary antibody to α‐SMA (A2547—clone 1A4; Sigma‐Aldrich) diluted at 1:400, washed and then followed by secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti‐mouse IgG, 1:1000; Life Technologies, Oregon, USA) before mounting (Vectashield with DAPI, Cambridgeshire, UK). For analysis of α‐SMA immunostaining, images of bronchioles that were of appropriate size to be contained within fields of view under high‐power magnification (×20) were obtained from the same region of the lung using a ZEISS Axiostar plus microscope. For image analysis, collagen staining from Masson's trichrome‐stained images was isolated by colour deconvolution. Derived images from colour deconvolution were made binary, and the total area of the bronchiole and subepithelial region showing positive α‐SMA or Masson's staining was manually selected. The percentage area with positive stain was then determined by Image J Analysis Software (National Institute of Health, Maryland, USA). A minimum of five bronchioles were used from each lung for analysis.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6 for Windows (GraphPad Software Inc, California, USA) using one‐way ANOVA with post hoc tests or Student's t tests as appropriate. Observed change was considered significant with P < 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Bronchial epithelial cells up‐regulate Endothelin‐1 expression in response to A fumigatus spores

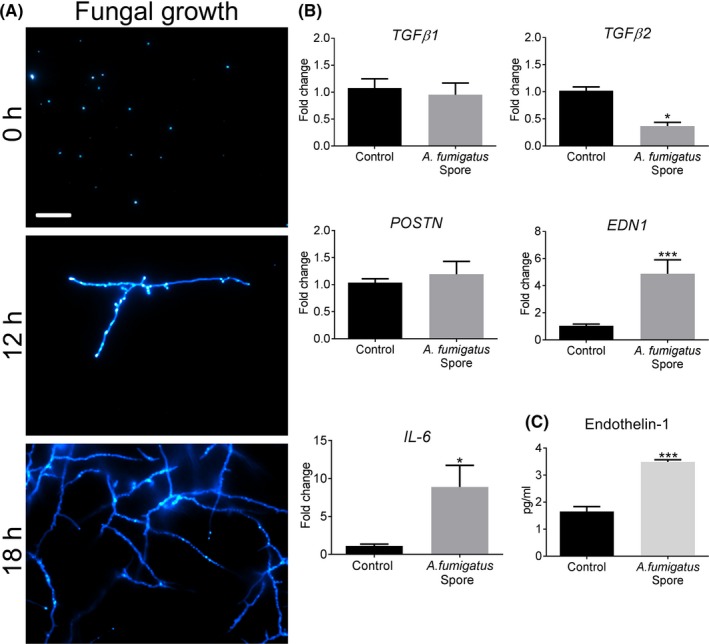

We initially determined whether A fumigatus induced human BECs to express pro‐fibrogenic growth factors in vitro. Cells were exposed to spores and expression of TGF‐β1 and TGF‐β2, periostin and ET‐1 assessed by qPCR. At 12 hours, A fumigatus spores had undergone germination, showing progressive branching of hyphae which gradually evolved into a mycelial mesh by 18 hours (Figure 2A). In response to A fumigatus spores, there was no increase in gene expression for TGF‐β1 or periostin and surprisingly a down‐regulation of TGF‐β2 by BECs (Figure 2B). In contrast, A fumigatus spores caused a highly significant increase in ET‐1 gene expression and the pro‐inflammatory cytokine, IL6 (Figure 2B). Furthermore, in response to A fumigatus, ET‐1 protein production was significantly increased at 24 hours compared with control (Figure 2C). In parallel, BECs were exposed to A fumigatus culture filtrate containing secreted products, and again, there was a significant increase in gene expression and protein production of ET‐1 but not of the other growth factors assessed (Figure S1).

Figure 2.

ET‐1 is up‐regulated in human bronchial epithelial cells exposed to Aspergillus fumigatus germinating spores. A, Confocal microscopy of live, germinating spores seeded onto BEC monolayers and stained with calcofluor‐white at 0, 12 and 18 h. Note the progressive emergence of hyphal extensions (Scale bar = 100 μm). B, In response to A fumigatus germinating spore exposure for 12 h, BECs increased gene expression of EDN1 (***P < 0.001, n = 6) and pro‐inflammatory mediator, IL‐6 (*P ≤ 0.05, n = 6) as assessed by qPCR. Gene expression of other pro‐fibrogenic mediators, TGF‐β1 and POSTN, was unchanged whilst TGF‐β2 expression was significantly reduced (*P < 0.05, n = 6) relative to control. C, In response to A fumigatus germinating spores, BECs significantly increased the production of ET‐1 after 24 h (***P < 0.001, n = 6)

3.2. Induction of Endothelin‐1 in a murine A fumigatus spore inhalation model

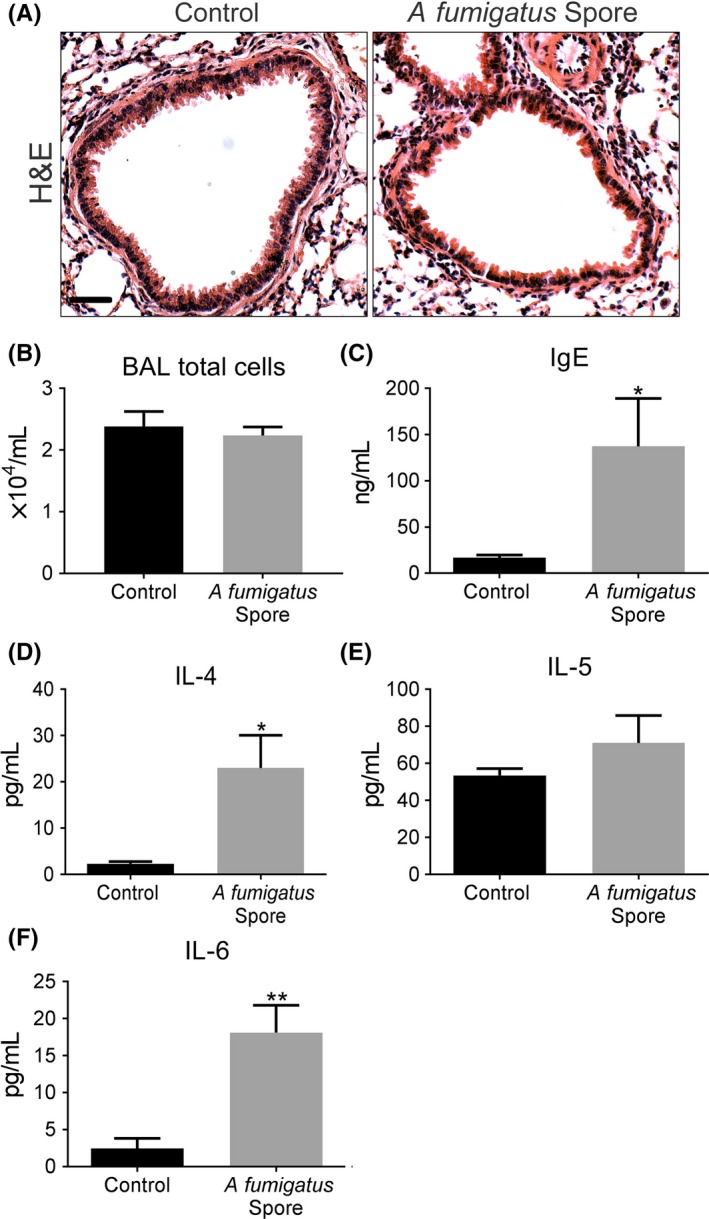

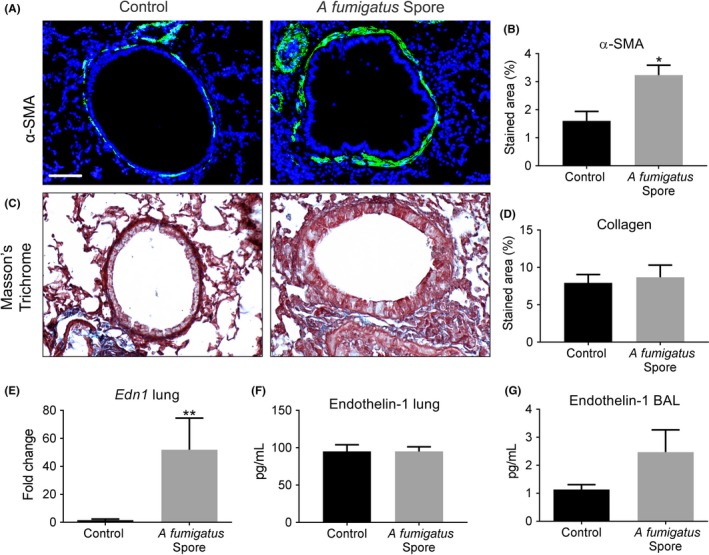

Using a murine model of repeated spore inhalation (Figure 1A), we next analysed the ability of A fumigatus to up‐regulate pro‐fibrogenic growth factors in vivo. Mouse airway exposure to A fumigatus spores, over the course of 3 weeks, was associated with a mild inflammatory response of the peribronchiolar region (Figure 3A) with no significant difference in total cell count in BAL compared with control (Figure 3B). Exposure to spores was also associated with a relatively mild, but significant increase in the level of pro‐inflammatory cytokines, IL4 and IL6, assessed in lung homogenate, as well as a significant rise in total serum IgE but not IL5 (Figures 3C‐F). A fumigatus spore exposure also significantly enhanced α‐SMA localization around the airways (Figure 4A‐B), although no significant change in peribronchiolar collagen deposition was detected by image analysis (Figure 4C‐D). This relatively mild remodelling of the airways in response to A fumigatus spores was accompanied by significantly increased lung ET‐1 gene expression (Figure 4E). However, the increase in gene expression was not accompanied by a significant increase in ET‐1 protein level in lung homogenate or BAL compared with controls (Figure 4F‐G). Similar to findings in vitro, A fumigatus spores failed to induce a significant up‐regulation of gene expression for TGF‐β1, TGF‐β2 and periostin in murine lung tissue (Figure S2). Together, these findings indicate that airway ET‐1 gene expression was specifically up‐regulated in response to A fumigatus spores.

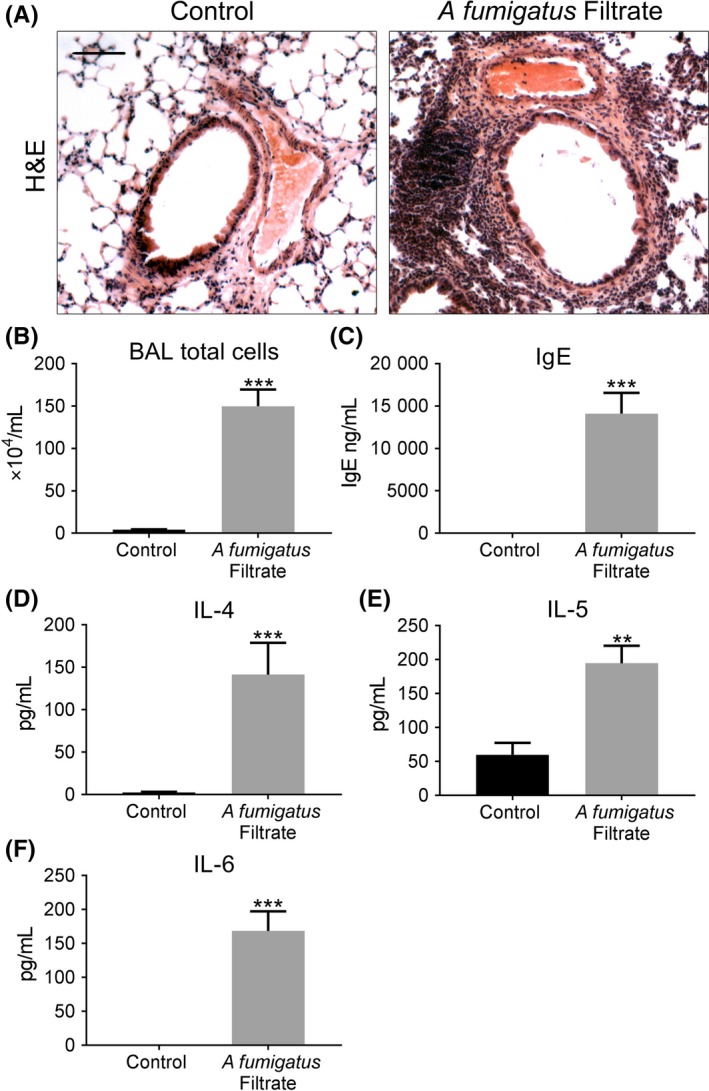

Figure 3.

Aspergillus fumigatus spores elicit a mild inflammatory and allergic response in a murine inhalation model. A, Representative H&E images, depicting the relatively mild peribronchiolar inflammatory response in airways exposed to A fumigatus spores (Scale bar = 50 μm). B, Total BAL cell counts were similar in response to spore exposure and control. C‐F, Exposure to spores caused a mild, but a significant increase in serum IgE (*P < 0.05, n = 5) and IL4 (*P < 0.05, n = 5) and IL6 (**P < 0.01, n = 5) levels in homogenized lung, but no change for IL5 compared with control

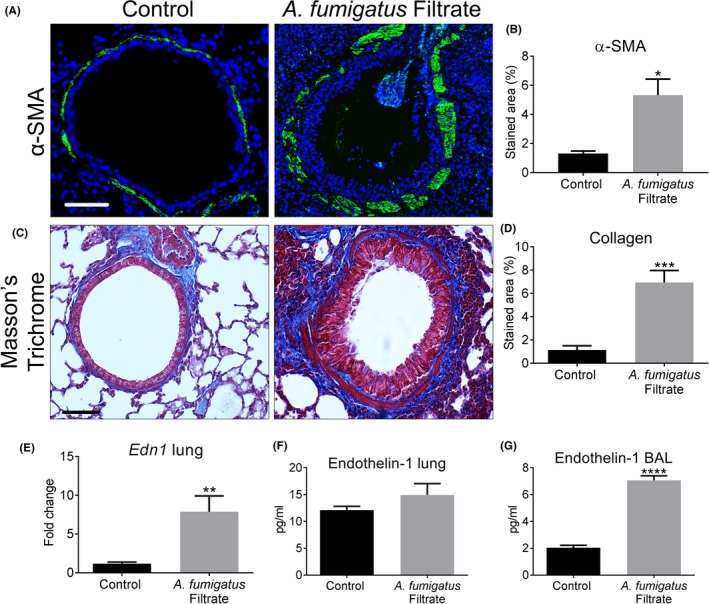

Figure 4.

Aspergillus fumigatus spores cause limited remodelling of the airways and Endothelin‐1 induction in a murine inhalation model. A‐B, Repeated exposure to A fumigatus spores significantly increased peribronchiolar α‐SMA (green and counterstained for DAPI to visualize nuclei blue; *P < 0.05; n = 5) compared with control (Scale bar = 50 μm). C‐D, No detectable change in collagen deposition around airways following spore exposure was detected by image analysis of Masson's trichrome‐stained sections. E‐G, A significant increase in lung Edn1 gene expression (**P < 0.01, n = 5) was found by qPCR in spore exposed mice but no significant increase in ET‐1 protein in total lung homogenate or BAL compared with control mice

3.3. Aspergillus fumigatus culture filtrate drives robust airway inflammation and remodelling associated with Endothelin‐1 induction

We conceptualized that rapid fungal spore clearance before adequate germination in the inhalation model may prevent sufficient exposure time of the airways to A fumigatus mediators. We therefore used a different inhalation model which involved repeated airway exposure to A fumigatus culture filtrate in vivo over the course of a 5‐week period (Figure 1B). Prominent peribronchiolar inflammation was evident in culture filtrate exposed lungs (Figure 5A) associated with a significant increase in total cell counts in BAL compared with that from control lungs (Figure 5B). Differential BAL cell counts revealed that this overall increase was associated with a decrease in the number of macrophages concomitant with an increase in the number of eosinophils, neutrophils and lymphocytes (Figure S3). Filtrate‐induced inflammation was associated with a robust and highly significant increase in pro‐inflammatory cytokines, IL4, IL5 and IL6, in lung homogenate and total serum IgE to levels far greater than that found in response to spores indicating a robust allergic response (Figure 5C‐F). Furthermore, significantly increased α‐SMA localization was detected around the airways accompanied by profound collagen deposition, hallmarks of airway remodelling (Figure 6A‐D). Gene expression of lung ET‐1 was significantly increased in culture filtrate exposed lungs (Figure 6E). Similar to the spore model, lung homogenate ET‐1 protein was not changed (Figure 6F), but interestingly, ET‐1 levels in BAL were significantly increased which may suggest an increase in bronchial epithelial‐derived ET‐1 or increased production by inflammatory cells in BAL (Figure 6G). We also assessed gene expression of TGF‐β1, TGF‐β2 and periostin in the lungs of mice exposed to A fumigatus culture filtrate. Similar to the spore inhalation model, culture filtrate exposure did not increase the expression of these growth factors (Figure S4).

Figure 5.

Robust inflammation and allergic response in a murine A fumigatus culture filtrate inhalation model. A, Representative H&E images of control and A fumigatus culture filtrate exposed airways (Scale bar = 50 μm). Note the profound peribronchiolar and perivascular inflammation apparent in culture filtrate exposed airways. B, Total cell counts from Giemsa‐stained cytospins showing a significant increase in total cell number (***P < 0.001, n = 5), C‐F, Total serum IgE (***P < 0.001, n = 5) and pro‐inflammatory and Th2‐promoting cytokines, IL4 (***P < 0.001, n = 5), IL‐5 (**P < 0.01, n = 5) and IL‐6 (***P < 0.001, n = 5) were all significantly increased in the lungs of mice exposed to culture filtrate compared with control

Figure 6.

Extensive airway remodelling in mice exposed to Aspergillus fumigatus culture filtrate. A‐B, Culture filtrate caused a noticeable increase in peribronchiolar α‐SMA localization (green and counterstained for DAPI to visualize nuclei, blue). compared with control which was found to be significant following image analysis (*P < 0.05, n = 5). C‐D, Culture filtrate exposed bronchioles showed extensive collagen deposition on Masson's trichrome‐stained sections confirmed to be significantly increased compared with control by image analysis (***P < 0.001, n = 5; Scale bar = 50 μm). This profound airway wall remodelling in culture filtrate exposed mice was associated with a significant increase in E, Edn1 gene expression in homogenized lung (**P < 0.001, n = 5), F, no change in total lung homogenate ET‐1 protein, but G, a robust increase in ET‐1 protein in BAL (****P < 0.0001, n = 5) compared with control

3.4. Endothelin receptor A (ETA) antagonism diminishes A fumigatus‐induced airway pathology

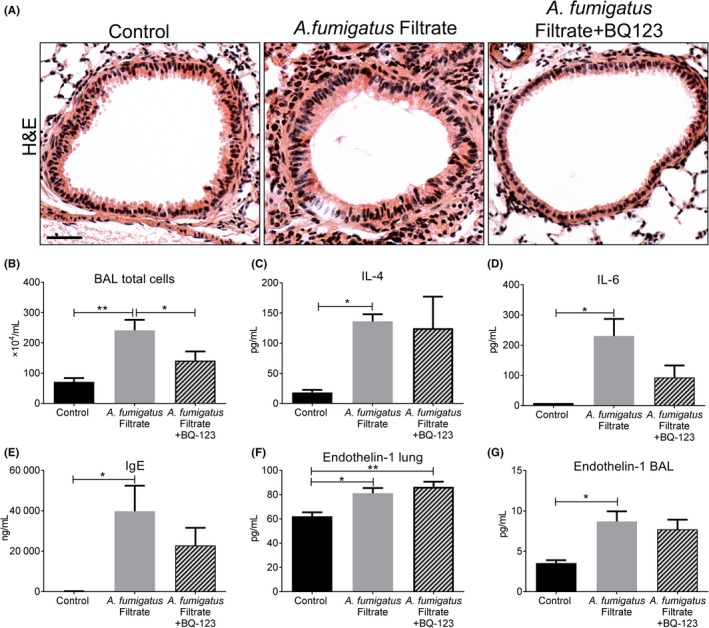

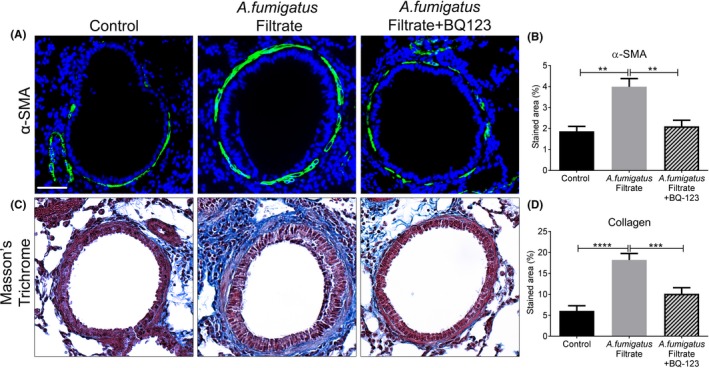

We hypothesized that ET‐1 likely facilitates A fumigatus driven airway pathology. To test this theory, mice were treated intranasally with BQ‐123, an ETA receptor antagonist, prior to each A fumigatus culture filtrate exposure. Pre‐treatment with BQ‐123 reduced the extent of peribronchiolar inflammatory infiltration and significantly reduced total BAL cell count compared to mice receiving filtrate alone (Figure 7A‐B). Assessment of BAL differential cell counts revealed that this reduction was due to a significant decrease in the number of macrophages, neutrophils and lymphocytes (Figure S5). Reduced inflammation was not associated with a significant reduction in IL4, IL6 or total serum IgE in the BQ‐123‐treated group compared with culture filtrate alone group (Figure 7C‐E). Antagonism of ET‐1 receptor caused a modest, but significant increase in lung homogenate ET‐1, but did not alter BAL ET‐1 levels compared with mice receiving culture filtrate (Figure 7F‐G). We next assessed whether BQ‐123 reduced airway remodelling in response to A fumigatus culture filtrate. Subepithelial α‐SMA distribution (Figure 8A‐B) and collagen deposition (Figure 8C‐D) induced by culture filtrate exposure were both significantly diminished and often undetectable in the airways of mice pre‐treated with BQ‐123. These findings suggest that ETA antagonism successfully diminishes the inflammatory response and subepithelial remodelling induced by A fumigatus secreted products.

Figure 7.

Endothelin‐1 receptor antagonism moderates inflammation and allergic response to Aspergillus fumigatus. A, Representative H&E images showing exposure to A fumigatus culture filtrate caused extensive peribronchiolar inflammation which was far less apparent following BQ‐123 treatment (Scale bar = 50 μm). B, Mice receiving culture filtrate alone showed a significant increase in total BAL cell count (**P < 0.01, n = 5) which was significantly reduced by BQ‐123 treatment relative to culture filtrate group (*P < 0.05, n = 5). C, Exposure to culture filtrate caused a significant induction of IL4 (*P < 0.05, n = 5), which was unchanged with BQ‐123 treatment and D, a significant induction of IL6 (**P < 0.01, n = 5) that was decreased by BQ‐123 abet not significantly. E, Culture filtrate caused a significant induction of total serum IgE (*P < 0.05, n = 5) which also showed a trend for reduction following BQ‐123 treatment. F, A fumigatus caused a significant induction of ET‐1 protein in the lung (*P < 0.05, n = 5), which increased further with BQ‐123 treatment (**P < 0.01, n = 5). G, Relative to controls, ET‐1 was significantly increased in BAL from mice exposed to culture filtrate (*P < 0.05, n = 5) and did not statistically significant change in the BQ‐123‐treated group

Figure 8.

Endothelin‐1 receptor antagonism obliterates Aspergillus fumigatus‐induced airway wall remodelling. A, Representative images of bronchioles from control, culture filtrate exposed or culture filtrate with BQ‐123 pre‐treatment mice showing α‐SMA localization (green) and counterstained for DAPI to visualize nuclei (blue). B, Compared with controls, A fumigatus filtrate caused a significant increase in peribronchiolar α‐SMA (**P < 0.01, n = 5) which was significantly decreased in the A fumigatus filtrate + BQ‐123 group compared with culture filtrate group (**P < 0.01, n = 5). C, Representative images of bronchioles from control, A fumigatus filtrate or A fumigatus filtrate + BQ‐123‐treated mice stained by Masson's trichrome. D, Exposure to A fumigatus filtrate caused a profound and significant increase in collagen (****P < 0.0001, n = 5) which was significantly diminished in the BQ‐123‐treated group (***P < 0.001, n = 5)

4. DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrated that A fumigatus spores and culture filtrate caused a highly specific up‐regulation of ET‐1 in cultured human airway epithelial cells. By modelling fungal‐induced allergic disease in mice, we corroborated these findings in vivo and showed that A fumigatus driven airway inflammation and remodelling was associated with a targeted up‐regulation of ET‐1. Based on the notion that ET‐1 is central to A fumigatus driven airway remodelling, we delivered an ET receptor A (ETA) antagonist, BQ‐123, prior to exposing mice to A fumigatus. We demonstrated for the first time that antagonism of ETA prevents A fumigatus‐induced inflammation and remodelling of the airways.

Previously regarded as a mere bystander, the airway epithelium is now recognized as pivotal in driving the asthma phenotype.10, 11, 12 Furthermore, acting as an epithelial‐mesenchymal trophic unit, injured airway epithelial cells signal to underlying mesenchymal cells and vice versa.14 A fumigatus up‐regulates a number of key cytokines in airway epithelial cells.15, 16 Intriguingly in the present study, we found that both A fumigatus spores and culture filtrate also caused an up‐regulation of ET‐1 in airway epithelial cells, with no significant change detected for TGF‐β1 or periostin and a decrease in TGF‐β2 compared with untreated controls. We next substantiated the up‐regulation of ET‐1 found in vitro using murine models of allergic inflammation mediated by A fumigatus exposure. Both a spore inhalation model33 and our previously published model of culture filtrate exposure18 showed a significant up‐regulation of ET‐1 gene expression compared with controls. In accord with our in vitro findings, TGF‐β1 and β2 and periostin expressions were not significantly altered. Up‐regulation of ET‐1 expression was accompanied by Th2 cytokine and IgE induction and extensive remodelling of the airways, with subepithelial collagen deposition and smooth muscle hypertrophy, highly pronounced in the culture filtrate model. To our knowledge, this is the first report of an up‐regulation of ET‐1 by human airway epithelial cells and in BAL from murine lungs exposed by A fumigatus. These findings may indicate an epithelial source of this growth factor in vivo. ET‐1 has been found in high levels in children with asthma24 and also increased during exacerbation of asthma in adults.25 Furthermore in human asthmatic airways, ET‐1 is located primarily in the bronchial epithelium34 with its expression increased in steroid‐refractory asthma.35 As well as the epithelium, ET‐1 is produced by a number of lung cell types including pulmonary vascular endothelial cells, macrophages, neutrophils and fibroblasts.36, 37, 38, 39 ET‐1 is also reported to drive macrophage cytokine production and recruitment of lymphocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils in ovalbumin‐sensitized mice.40 In the current study, macrophages, neutrophils and lymphocytes were all increased in the BAL of A fumigatus‐exposed mice. It is therefore possible that ET‐1 was derived from the bronchial epithelium and contributes to the recruitment of immune cells found in BAL and/or was produced by these immune cells.

ET‐1 signals via ET receptor A (ETA), expressed by many cell types including vascular and airway smooth muscle leading to vaso‐ and bronchoconstriction but can also signal by ET receptor B (ETB), predominately expressed by the endothelium.41 In the current study, up‐regulation of ET‐1 in mice exposed to A fumigatus culture filtrate was associated with an increased inflammatory response. Treatment with ETA antagonist, BQ‐123, diminished the recruitment of inflammatory cells around the airways and total cell counts assessed in lung lavage. Differential cell counts showed that this was due to a significant decline in the number of macrophages, neutrophils and lymphocytes following BQ‐123 treatment. A range of immune cells including macrophages, dendritic cells and lymphocytes also express ET receptors,42 providing the signalling mechanism by which up‐regulated ET‐1 may drive early inflammation and ultimately an allergic phenotype. It may also be the means by which BQ‐123 diminished inflammation and allergy. These finding support those of others where inhibition of ET‐1 with BQ‐123 and a dual ETA and ETB blockade with SB‐209670, reduced airway eosinophilia and neutrophilia in ovalbumin‐sensitized mice.43 Furthermore, in a mouse model of house dust mite sensitization, eosinophilia and airway hyperresponsiveness were alleviated by the dual ET‐1 receptor antagonist SB‐217242.44 Interestingly, eosinophil cell count was not significantly reduced by BQ‐123 in the current study although there was only a modest increase with culture filtrate exposure. Overall, our findings point to an important pathophysiological role for ET‐1 in the development of airway inflammation in A fumigatus‐induced allergic asthma.

As well as mediating an inflammatory response, our in vivo findings support a role for A fumigatus‐induced ET‐1 in mediating subepithelial fibrosis. Antagonism of ETA with BQ‐123 caused near‐complete resolution of A fumigatus‐induced subepithelial collagen deposition and diminished α‐SMA‐positive immunostaining around airways. Previous in vitro studies showed that ET‐1 elicits fibroblast proliferation, differentiation into myofibroblasts and induction of contractile activity.36, 45, 46, 47 Intriguingly, ETA antagonism also inhibited the differentiation of isolated blood‐derived fibrocytes into myofibroblasts in vitro.48 Furthermore, adenovirus‐mediated pulmonary up‐regulation of ET‐1 was sufficient to drive extensive inflammation coupled with remodelling of the airways.49 Of relevance, a study involving ovalbumin exposure in mice overexpressing smad 2, a downstream TGF‐β signalling molecule, displayed reduced airway wall remodelling following ET‐1 antagonism.50 Lastly, cultured bronchial epithelial cells were shown to display reduced migration and proliferation in the presence of ET‐1, suggesting this factor could potentially lead to defective repair of the lung epithelium resulting in enhanced remodelling.51 Taken together, such data point to a possible role for ET‐1 in the epithelial‐mesenchymal trophic unit, where A fumigatus‐induced activation of airway epithelium may trigger the production of ET‐1 that initiates a fibrogenic response in the subepithelial layer. These experimental observations are interesting when considering the pathophysiology of childhood asthma, where remodelling of the airways may occur in parallel or precede inflammation.2 Our findings build on these previous reports and show that antagonizing ETA is an effective treatment to combat both inflammation and remodelling caused by inhaled fungal particles. This finding is particularly significant for difficult‐to‐treat asthma patients, quite often sensitized to airborne fungi.

In our hands, the extent of airway inflammation and remodelling was relatively mild in the A fumigatus spore inhalation model. This may stem from rapid spore clearance by innate immune cells recruited to the airways, ultimately not providing sufficient time for complete spore germination and host sensitization.52 Shedding of the outer rodlet layer and exposure of carbohydrate moieties during germination are thought to be crucial steps in the host inflammatory response.53 Indeed, studies comparing repeated exposure to live or dead A fumigatus spores in pre‐sensitized mice have shown that germination is essential for allergic airway inflammation and remodelling.54 We assessed fungal burden 24 hours after final spore exposure and found no evidence of A fumigatus colonization of the lungs supporting this conclusion (data not shown). Repeated exposure to a high concentration of secreted fungal factors, as provided by the culture filtrate, was much more efficient in driving inflammation and airway remodelling than that found with the rapidly cleared spores.

It remains uncertain which secreted mediators from germinating spores and enriched in fungal culture filtrate may induce ET‐1 production but could include fungal protease allergens and/or secondary metabolic by‐products. We previously showed that deletion of specific protease activity from the culture filtrate of a genetically modified A fumigatus isolate curtailed epithelial damage and airway remodelling in the mouse inhalation model.18 Others have shown that proteases contained in various aeroallergens such as ragweed, cockroach and house dust mite, can activate PAR2, a seven‐transmembrane G‐coupled protein receptor. Furthermore, A fumigatus extract has been shown to activate this receptor in airway epithelial cells and biases the cells to mediate a Th2 response.55 Of note, activation of this receptor in keratinocytes stimulated by house dust mite‐derived proteases increased ET‐1 production in vitro. Therefore, activation of PAR2 by A fumigatus proteases may be a proposed mechanism leading to ET‐1 induction. However, in the current study, we used culture filtrate derived from A fumigatus strain, AF293, which we previously showed lacked protease activity when grown in minimal culture media.56 With this in mind, we suggest that A fumigatus‐derived proteases may, in part, be involved in germinating spore‐mediated ET‐1 production but A fumigatus‐derived soluble factors other than proteases may also be driving ET‐1 production in the culture filtrate studies.

Secreted components in culture filtrate such as carbohydrate moieties and/or toxins may be driving induction of ET‐1 via activation of pattern recognition receptors such as Dectin‐1. For instance, in a similar allergic model of chronic lung exposure to live A fumigatus conidia, β‐glucan recognition via Dectin‐1 resulted in the induction of multiple proallergic and pro‐inflammatory mediators.57 In addition, gliotoxins and other metabolic by‐products are important A fumigatus virulence factors known to interfere with epithelial integrity58 and trigger the release of pro‐inflammatory mediators53 and possibly pro‐fibrogenic factors such as ET‐1. In vivo, where epithelial‐fibroblast crosstalk occurs, apoptosis of BECs may contribute fibroblast activation and fibrosis.59 We did not notice overt denuding of the epithelium in mice treated with A fumigatus; however, it is possible that A fumigatus‐induced ET‐1 and ultimately fibrosis are first initiated by transient apoptosis. Interestingly, gliotoxins have been shown to accentuate ovalbumin‐induced airway inflammation, Th2 sensitization and airway remodelling in a murine model.60 Of note, mechanical stress also induces the selective production of ET‐1 by bronchial epithelial cells in culture61 and ET‐1 was found to decrease bronchial epithelial cell proliferation and migration in vitro.51 Therefore, loss of bronchial epithelial cell integrity may induce ET‐1 production leading to subepithelial fibrosis and impaired epithelial repair. Lastly, TNF‐α is a known inducer of ET‐1 and this mediators has been shown to be up‐regulated in transformed human airway cells on exposure to germinating A fumigatus spores.53 Whether ET‐1 is induced indirectly via an early induction of TNF‐α in BECs exposed to A fumigatus may be another possible mechanism which requires further investigation.

It may seem surprising that there was no observable increase in expression of TGF‐β1 and TGF‐β2 and periostin when they are known to be associated with fibrotic response in multiple organs. It is plausible that the timing of analysis was a limitation, and a later time‐point may have shown an increased expression. However, evidence suggests that TGF‐β was not up‐regulated in mice exposed to A fumigatus spores unless they were pre‐sensitized by fungal extract intra‐peritoneally and subcutaneously.62 Furthermore, periostin does not appear to be essential for A fumigatus‐induced subepithelial fibrosis as mice deficient in periostin demonstrated the same extent of airway remodelling as wild‐type mice.32

Although our studies indicate an important role for ET‐1 in the aetiology of airway disease, there are several experimental limitations. In the current study, we used cultures of healthy human epithelial cells. Asthmatic nasal and bronchial epithelial cells are reported to produce heightened levels of the growth factors associated with fibrosis (TGF‐β2, periostin and VEGF) at baseline and in response to IL4/13 compared with healthy cells.63 Furthermore, ET‐1 release was found to be higher from unstimulated asthmatic epithelial cells compared to control cells.64 With these studies in mind, it is likely that if we had used asthmatic epithelial cultures, we may have observed an even greater amplitude ET‐1 production in response to A fumigatus. Furthermore, submerged alveolar epithelial cultures showed a dampened inflammatory response compared to those at air‐liquid interface (ALI) following an oxidative stress response with zinc oxide nanoparticles.65 Therefore, BECs grown at ALI are likely to have shown an even greater induction of ET‐1. The mouse models used in the current study, also fast‐track the allergic phenotype and recapitulate allergic features that may be comparable to some aspects of the disease, but by no means represent the complexity of asthma in people. Heightened exposure to fungal allergens may occur in asthma and other lung pathologies where pre‐existing mucus hypersecretion or cavitation provides the ideal environment for A fumigatus spores to thrive and avoid being cleared. Indeed, it is reported that 60%‐80% of asthmatics with fungal sensitization have A fumigatus present in sputum, suggesting that such people are continuously exposed to A fumigatus‐derived products at high concentrations over a long period of time.6

Herein, we have demonstrated for the first time that A fumigatus caused a robust up‐regulation of ET‐1 by bronchial epithelial cells and in murine lung. Antagonism of ETA caused a profound decrease in inflammation and subepithelial fibrosis, highlighting the therapeutic potential for targeting ET‐1 in fungal‐sensitized asthma. Whether also blocking ETB with a dual antagonist would have produced an even greater effect is not known. Although other studies have shown that antagonism of ETB using BQ‐788 did not inhibit differentiation of fibrocytes into myofibroblasts48 and failed to influence airway inflammation43 suggesting that ETB may not play a major role in ET‐1‐induced airway pathology. Of note, a small clinical trial using the dual receptor antagonist, bosentan, to treat people with asthma showed no improvement in the symptoms assessed66. However, this trial was limited by not reporting the specific allergic sensitization of participants and the fact that bosentan inhibits both ET‐1 receptors. Further studies assessing the efficacy of selective ETA antagonism, specifically in A fumigatus‐sensitized asthma may be warranted.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Bioimaging Facility microscopes used in this study were purchased with grants from BBSRC, Wellcome and the University of Manchester Strategic Fund. We would like to thank Peter March, Roger Meadows and Steven Marsden for their help with microscopy. We also thank Peter Walker and Grace Bako for support with histology. A special thanks goes to Raymond Hodgkiss for technical assistance. This project was funded by MRC and Novartis.

Labram B, Namvar S, Hussell T, Herrick SE. Endothelin‐1 mediates Aspergillus fumigatus‐induced airway inflammation and remodelling. Clin Exp Allergy. 2019;49:861–873. 10.1111/cea.13367

REFERENCES

- 1. Loftus PA, Wise SK. Epidemiology and economic burden of asthma. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015;5(Suppl 1):S7‐S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saglani S, Payne DN, Zhu J, et al. Early detection of airway wall remodeling and eosinophilic inflammation in preschool wheezers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(9):858‐864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pohunek P, Warner JO, Turzikova J, Kudrmann J, Roche WR. Markers of eosinophilic inflammation and tissue re‐modelling in children before clinically diagnosed bronchial asthma. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2005;16(1):43‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bergeron C, Tulic MK, Hamid Q. Airway remodelling in asthma: from benchside to clinical practice. Can Respir J. 2010;17(4):e85‐e93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shifren A, Witt C, Christie C, Castro M. Mechanisms of remodeling in asthmatic airways. J Allergy (Cairo). 2012;2012:316049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Denning DW, Pashley C, Hartl D, et al. Fungal allergy in asthma‐state of the art and research needs. Clin Transl Allergy. 2014;4:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Gupta D, Jindal SK. Aspergillus hypersensitivity and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in patients with bronchial asthma: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13(8):936‐944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brakhage AA, Langfelder K. Menacing mold: the molecular biology of Aspergillus fumigatus . Annu Rev Microbiol. 2002;56:433‐455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kosmidis C, Denning DW. The clinical spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Thorax. 2015;70(3):270‐277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Parker D, Prince A. Innate immunity in the respiratory epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45(2):189‐201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schleimer RP, Kato A, Kern R, Kuperman D, Avila PC. Epithelium: at the interface of innate and adaptive immune responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(6):1279‐1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hallstrand TS, Hackett TL, Altemeier WA, Matute‐Bello G, Hansbro PM, Knight DA. Airway epithelial regulation of pulmonary immune homeostasis and inflammation. Clin Immunol. 2014;151(1):861‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bertuzzi M, Hayes GE, Icheoku UJ, et al. Anti‐aspergillus activities of the respiratory epithelium in health and disease. J Fungi (Basel). 2018;4(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Holgate ST, Holloway J, Wilson S, Bucchieri F, Puddicombe S, Davies DE. Epithelial‐mesenchymal communication in the pathogenesis of chronic asthma. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2004;1(2):93‐98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen F, Zhang C, Jia X, et al. Transcriptome profiles of human lung epithelial cells A549 interacting with Aspergillus fumigatus by RNA‐Seq. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0135720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kauffman HF, Tomee JF, van de Riet MA, Timmerman AJ, Borger P. Protease‐dependent activation of epithelial cells by fungal allergens leads to morphologic changes and cytokine production. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105(6 Pt 1):1185‐1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Balenga NA, Klichinsky M, Xie Z, et al. A fungal protease allergen provokes airway hyper‐responsiveness in asthma. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Namvar S, Warn P, Farnell E, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus proteases, Asp f 5 and Asp f 13, are essential for airway inflammation and remodelling in a murine inhalation model. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45(5):982‐993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Minshall EM, Leung DY, Martin RJ, et al. Eosinophil‐associated TGF‐beta1 mRNA expression and airways fibrosis in bronchial asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;17(3):326‐333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Balzar S, Chu HW, Silkoff P, et al. Increased TGF‐beta2 in severe asthma with eosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(1):110‐117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Takayama G, Arima K, Kanaji T, et al. Periostin: a novel component of subepithelial fibrosis of bronchial asthma downstream of IL‐4 and IL‐13 signals. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118(1):98‐104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. James A, Janson C, Malinovschi A, et al. Serum periostin relates to type‐2 inflammation and lung function in asthma: data from the large population‐based cohort Swedish GA(2)LEN. Allergy. 2017;72(11):1753‐1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Redington AE, Springall DR, Ghatei MA, et al. Endothelin in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and its relation to airflow obstruction in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151(4):1034‐1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen WY, Yu J, Wang JY. Decreased production of endothelin‐1 in asthmatic children after immunotherapy. J Asthma. 1995;32(1):29‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aoki T, Kojima T, Ono A, et al. Circulating endothelin‐1 levels in patients with bronchial asthma. Ann Allergy. 1994;73(4):365‐369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fagan KA, McMurtry IF, Rodman DM. Role of endothelin‐1 in lung disease. Respir Res. 2001;2(2):90‐101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ashley SL, Wilke CA, Kim KK, Moore BB. Periostin regulates fibrocyte function to promote myofibroblast differentiation and lung fibrosis. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10(2):341‐351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coker RK, Laurent GJ, Shahzeidi S, et al. Transforming growth factors‐beta 1, ‐beta 2, and ‐beta 3 stimulate fibroblast procollagen production in vitro but are differentially expressed during bleomycin‐induced lung fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 1997;150(3):981‐991. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xu SW, Howat SL, Renzoni EA, et al. Endothelin‐1 induces expression of matrix‐associated genes in lung fibroblasts through MEK/ERK. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(22):23098‐23103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bentley JK, Chen Q, Hong JY, et al. Periostin is required for maximal airways inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(6):1433‐1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bottoms SE, Howell JE, Reinhardt AK, Evans IC, McAnulty RJ. Tgf‐Beta isoform specific regulation of airway inflammation and remodelling in a murine model of asthma. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(3):e9674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gordon ED, Sidhu SS, Wang ZE, et al. A protective role for periostin and TGF‐beta in IgE‐mediated allergy and airway hyperresponsiveness. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42(1):144‐155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Porter P, Susarla SC, Polikepahad S, et al. Link between allergic asthma and airway mucosal infection suggested by proteinase‐secreting household fungi. Mucosal Immunol. 2009;2(6):504‐517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Redington AE, Springall DR, Meng QH, et al. Immunoreactive endothelin in bronchial biopsy specimens: increased expression in asthma and modulation by corticosteroid therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100(4):544‐552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pegorier S, Arouche N, Dombret MC, Aubier M, Pretolani M. Augmented epithelial endothelin‐1 expression in refractory asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(6):1301‐1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shi‐wen X, Kennedy L, Renzoni EA, et al. Endothelin is a downstream mediator of profibrotic responses to transforming growth factor beta in human lung fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(12):4189‐4194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Marini M, Carpi S, Bellini A, Patalano F, Mattoli S. Endothelin‐1 induces increased fibronectin expression in human bronchial epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;220(3):896‐899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Giaid A, Polak JM, Gaitonde V, et al. Distribution of endothelin‐like immunoreactivity and mRNA in the developing and adult human lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1991;4(1):50‐58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Comellas AP, Briva A. Role of endothelin‐1 in acute lung injury. Transl Res. 2009;153(6):263‐271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sampaio AL, Rae GA, Henriques MM. Role of endothelins on lymphocyte accumulation in allergic pleurisy. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67(2):189‐195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Davenport AP, Hyndman KA, Dhaun N, et al. Endothelin. Pharmacol Rev. 2016;68(2):357‐418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Elisa T, Antonio P, Giuseppe P, et al. Endothelin receptors expressed by immune cells are involved in modulation of inflammation and in fibrosis: relevance to the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:147616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fujitani Y, Trifilieff A, Tsuyuki S, Coyle AJ, Bertrand C. Endothelin receptor antagonists inhibit antigen‐induced lung inflammation in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155(6):1890‐1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Henry PJ, Mann TS, D'Aprile AC, Self GJ, Goldie RG. An endothelin receptor antagonist, SB‐217242, inhibits airway hyperresponsiveness in allergic mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283(5):L1072‐L1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hafizi S, Wharton J, Chester AH, Yacoub MH. Profibrotic effects of endothelin‐1 via the ETA receptor in cultured human cardiac fibroblasts. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2004;14(4–6):285‐292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shi‐Wen X, Denton CP, Dashwood MR, et al. Fibroblast matrix gene expression and connective tissue remodeling: role of endothelin‐1. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116(3):417‐425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sun G, Stacey MA, Bellini A, Marini M, Mattoli S. Endothelin‐1 induces bronchial myofibroblast differentiation. Peptides. 1997;18(9):1449‐1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Weng CM, Chen BC, Wang CH, et al. The endothelin A receptor mediates fibrocyte differentiation in chronic obstructive asthma. The involvement of connective tissue growth factor. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(3):298‐308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lagares D, Busnadiego O, Garcia‐Fernandez RA, Lamas S, Rodriguez‐Pascual F. Adenoviral gene transfer of endothelin‐1 in the lung induces pulmonary fibrosis through the activation of focal adhesion kinase. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;47(6):834‐842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gregory LG, Jones CP, Mathie SA, Pegorier S, Lloyd CM. Endothelin‐1 directs airway remodeling and hyper‐reactivity in a murine asthma model. Allergy. 2013;68(12):1579‐1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dosanjh A, Zuraw B. Endothelin‐1 (ET‐1) decreases human bronchial epithelial cell migration and proliferation: implications for airway remodeling in asthma. J Asthma. 2003;40(8):883‐886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hohl TM, Van Epps HL, Rivera A, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus triggers inflammatory responses by stage‐specific beta‐glucan display. PLoS Pathog. 2005;1(3):e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bellanger AP, Millon L, Khoufache K, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus germ tube growth and not conidia ingestion induces expression of inflammatory mediator genes in the human lung epithelial cell line A549. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58(Pt 2):174‐179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pandey S, Hoselton SA, Schuh JM. The impact of Aspergillus fumigatus viability and sensitization to its allergens on the murine allergic asthma phenotype. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:619614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Homma T, Kato A, Bhushan B, et al. Role of Aspergillus fumigatus in triggering protease‐activated receptor‐2 in airway epithelial cells and skewing the cells toward a T‐helper 2 bias. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;54(1):60‐70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Farnell E, Rousseau K, Thornton DJ, Bowyer P, Herrick SE. Expression and secretion of Aspergillus fumigatus proteases are regulated in response to different protein substrates. Fungal Biol. 2012;116(9):1003‐1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lilly LM, Gessner MA, Dunaway CW, et al. The beta‐glucan receptor dectin‐1 promotes lung immunopathology during fungal allergy via IL‐22. J Immunol. 2012;189(7):3653‐3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gauthier T, Wang X, Sifuentes Dos Santos J, et al. Trypacidin, a spore‐borne toxin from Aspergillus fumigatus, is cytotoxic to lung cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e29906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kuwano K. Epithelial cell apoptosis and lung remodeling. Cell Mol Immunol. 2007;4(6):419‐429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Schutze N, Lehmann I, Bonisch U, Simon JC, Polte T. Exposure to mycotoxins increases the allergic immune response in a murine asthma model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(11):1188‐1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tschumperlin DJ, Shively JD, Kikuchi T, Drazen JM. Mechanical stress triggers selective release of fibrotic mediators from bronchial epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28(2):142‐149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hogaboam CM, Blease K, Mehrad B, et al. Chronic airway hyperreactivity, goblet cell hyperplasia, and peribronchial fibrosis during allergic airway disease induced by Aspergillus fumigatus . Am J Pathol. 2000;156(2):723‐732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lopez‐Guisa JM, Powers C, File D, Cochrane E, Jimenez N, Debley JS. Airway epithelial cells from asthmatic children differentially express proremodeling factors. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(4):990‐997. e996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Vittori E, Marini M, Fasoli A, De Franchis R, Mattoli S. Increased expression of endothelin in bronchial epithelial cells of asthmatic patients and effect of corticosteroids. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146(5 Pt 1):1320‐1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lenz AG, Karg E, Brendel E, et al. Inflammatory and oxidative stress responses of an alveolar epithelial cell line to airborne zinc oxide nanoparticles at the air‐liquid interface: a comparison with conventional, submerged cell‐culture conditions. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:652632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Coyle TB, Metersky ML. The effect of the endothelin‐1 receptor antagonist, bosentan, on patients with poorly controlled asthma: a 17‐week, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled crossover pilot study. J Asthma. 2013;50(4):433‐437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials