Abstract

Singlet oxygen (1O2) causes a major fraction of the parasitic chemistry during the cycling of non‐aqueous alkali metal‐O2 batteries and also contributes to interfacial reactivity of transition‐metal oxide intercalation compounds. We introduce DABCOnium, the mono alkylated form of 1,4‐diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (DABCO), as an efficient 1O2 quencher with an unusually high oxidative stability of ca. 4.2 V vs. Li/Li+. Previous quenchers are strongly Lewis basic amines with too low oxidative stability. DABCOnium is an ionic liquid, non‐volatile, highly soluble in the electrolyte, stable against superoxide and peroxide, and compatible with lithium metal. The electrochemical stability covers the required range for metal–O2 batteries and greatly reduces 1O2 related parasitic chemistry as demonstrated for the Li–O2 cell.

Keywords: DABCOnium, electrochemistry, lithium batteries, quenchers, singlet oxygen

Oxides are the backbone of most cathodes for alkali‐ion batteries and their interfacial reactivity key for battery lifetime. Candidates include traditional Li‐stoichiometric transition‐metal oxides (TMOs) and the two intensely investigated directions of TMOs with oxygen redox and metal–O2 batteries, which both promise significantly higher energy storage.1 The metal–O2 batteries critically rely on reversibly forming/decomposing Li, Na, or K peroxide or superoxide at the cathode.1a,1f, 2 However, practically realizing such cells requires inhibition of the severe parasitic reactions, which compromise rechargeability, efficiency, and cycle life.

Reactivity of (su)peroxides has been perceived to be responsible for the parasitic reactions that decompose cell components in metal–O2 cells into alkali carbonates and carboxylates, which are hard to oxidize and accumulate on cycling.1a,1b,1f, 2b–2e, 3 (Su)peroxide's reactivities as strong nucleophiles and bases could, however, not fully explain the parasitic reactions.1f, 2b, 3b,3d Recently, the highly reactive singlet oxygen (1Δg or 1O2) was shown to cause a large fraction of the parasitic reactions; it forms at all stages of cycling at rates that resemble the rates of parasitic reactions.4 Superoxide disproportionation to Li2O2 was suggested as the source of 1O2, which has been shown to react with electrolyte and carbon.4a, 5 Furthermore, 1O2 is now also recognized to contribute to interfacial reactivity of TMO intercalation materials.6 Fighting parasitic chemistry in batteries requires therefore neutralizing the 1O2.

Singlet oxygen is found in biological systems that use O2 reduction and evolution for energy storage.7 Life has evolved strategies to protect itself against this harmful chemical using chemical trapping and physical quenching agents, such as tocopheroles and carotenes. Analogous agents also work for man‐made systems.8 Traps uptake 1O2 into stable, innocuous adducts and are hence gradually consumed.4a, 7, 8, 9 For example, 9,10‐dimethylanthracene (DMA) has been shown to selectively form its endoperoxide (DMA‐O2).10 However, at the rate of 1O2 formation in batteries the DMA is quickly consumed. Physically deactivating (quenching) 1O2 to triplet oxygen (3O2) is preferred since the quencher is not consumed and no new products accumulate. Radiationless physical quenching follows three mechanisms that convert the excess energy of 1O2 into heat:7, 10 electronic‐to‐vibrational (e–v) energy transfer (1O2 quenching by solvents, slow), charge transfer (CT) induced quenching (ca. 107 times faster than e–v), and electronic energy transfer (even faster, e.g., carotenes, unsuitable for electrochemical systems). Quenching suitable for electrochemical systems proceeds efficiently via a charge transfer (CT) mechanism. The quencher Q and 1O2 form a singlet encounter complex 1(Q1Δ)EC, followed by a singlet charge transfer complex 1(Q1Δ)CT, in which electronic charge is partially transferred to the oxygen. Energy is then released during the intersystem crossing (isc) to the triplet ground state complex 3(Q3Σ)CT, which dissociates to Q and 3O2 [Eq. (1)]

| (1) |

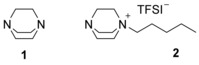

This mechanism applies to electron‐rich quenchers, such as amines, and has first been suggested for 1,4‐diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (DABCO, 1; Scheme 1), which has also been shown to be effective in aprotic media.4a, 6 Amines have been widely investigated and it was found that the partial charge transfer causes the quenching efficiency to correlate logarithmically with the ionization potential and hence oxidation potential.7 The efficiency drops by a factor of approximately 104 per volt increased oxidation potential. DABCO as one of the best known quenchers gets oxidized at approximately 3.6 V vs. Li/Li+ whereas approximately 4.2 V are typically required to recharge Li–O2 cells.1a, 3b, 11 Furthermore, cation interactions with strongly Lewis basic amines are known to impair quenching.7 The challenge for suitable amine quenchers is therefore to lower Lewis basicity, to raise the oxidation stability to around 4.2 V, and to counterbalance for the inevitably lower molar quenching efficiency by high concentrations. It should also be compatible with a lithium‐metal anode. Herein we show that monoalkylating the diamine DABCO to its onium salt (DABCOnium) achieves all these goals. Applied to a Li–O2 cell, it significantly reduces side reactions on discharge and charge.

Scheme 1.

Structures of the used quenchers DABCO (1) and PeDTFSI (pentyl DABCOnium TFSI) (2). Synthesis and IUPAC Names are given in the Supporting Information.

We prepared a pentyl DABCOnium species bearing a bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (TFSI−) anion (1‐pentyl‐1,4‐diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octan‐1‐ium TFSI 2, in the following abbreviated as PeDTFSI) according to a literature procedure as detailed in the Supporting Information.12 It is an ionic liquid with a melting point of 43 °C (Figure S3 in the Supporting Information) and widely miscible with glymes (oligo ethylene glycol dimethyl ether), which are frequently used for metal–O2 cells. As a proxy for Lewis basicity, we measured the donor number (DN) and obtained a value of 12.5 kcal mol−1 (see Supporting Information for details). This is similar to tetraethyleneglycol dimethylether (TEGDME), which has a DN of 12, but is much lower than that of tertiary amines, such as triethylamine (DN=61).13 PeDTFSI is, like DABCO, stable against superoxide, peroxide and 1O2 as determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figure S5, S6).

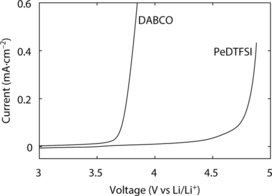

Linear sweep voltammetry was used to determine the electro‐chemical stability window of the quenchers (Figures 1 and Figure S7). Onset of reduction is in either case at around 0.5 V vs. Li/Li+ and hence sufficient for the O2 cathode (Figure S7). PeDTFSI is compatible with a metal lithium anode, which sustains low overpotentials on cycling (Figure S8). Monoalkylating DABCO raises the oxidation stability of the remaining tertiary amine moiety from around 3.6 V in DABCO by approximately 0.6 V to an onset potential of about 4.2 V in PeDTFSI (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Linear sweep voltammetry of 1 and 2 at a glassy carbon disc electrode in 0.1 m LiTFSI/TEGDME containing 2 mm of the quencher. The scan rate was 50 mV s−1.

We measured the quenching efficiency by monitoring the disappearance rate of the 1O2 trap DMA in presence of the quenchers during continuous photochemical 1O2 generation, an approach frequently used in the literature and detailed in the Supporting Information.10 In short, 1O2 was generated photochemically at a constant rate by illuminating (643 nm) O2 saturated TEGDME containing the photosensitizer PdII meso‐tetra(4‐fluorophenyl)tetrabenzoporphyrin,8 DMA, and either no other additive or the quencher. The DMA concentration was measured by means of the UV/Vis absorbance at 379 nm. The quenching efficiency was then obtained by comparing the DMA consumption rate with and without quencher.10 A prerequisite of the method is that the quencher does not significantly affect the 1O2 generation rate by reducing the lifetime of the excited sensitizer T1 state, which goes on to convert 3O2 into 1O2. Measuring the T1 lifetimes in presence of various quencher concentrations shows negligible influence of the quencher on 1O2 generation rate (see Figure S9 and S10 and discussion in the Supporting Information).

Figure 2 a shows the decay of DMA concentration with various PeDTFSI concentrations. Since DMA and the quencher compete to reacting with/quench 1O2, a slower decay of the DMA concentration indicates better a quenching efficiency and hence a larger 1O2 fraction quenched. Figure 2 b shows the thus obtained DMA decay rates without and with the quenchers and the quenched 1O2 fraction. 40 μm DABCO roughly halved the DMA decay rate, indicating that around 50 % of the 1O2 was quenched. The PeDTFSI concentration had to be increased to the mm range for a strong effect. With 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, and 0.38 m, the quenched 1O2 fractions were 9, 23, 56, and 86 %, respectively. PeDTFSI has a lower molar quenching efficiency than DABCO as expected from the higher oxidation potential. However, the high solubility of PeDTFSI allows for quenching the vast majority of the 1O2.

Figure 2.

a) 9,10‐dimethylanthracene (DMA) concentration versus time during 1O2 generation in the presence of various PeDTFSI concentrations to determine quenching efficiency. 80 μm DMA and the noted concentration of PeDTFSI in O2 saturated TEGDME containing 1 μm of the sensitizer palladium(II) meso‐tetra(4‐fluorophenyl)tetrabenzoporphyrin (Pd4F) were illuminated at 643 nm and the DMA concentration measured via the absorbance at 379 nm. b) Quenching efficiency expressed as DMA decay kinetics and fraction of 1O2 quenched for 40 μm DABCO and various PeDTFSI concentrations. DMA decay curves DABCO are given in Figure S11.

Ultimately, a suitable quencher needs to effectively decrease the amount of 1O2 related parasitic chemistry. Key measures for the extent of parasitic chemistry are deviations of the ratio of O2 consumed/evolved and (su)peroxide formed/decomposed per electron passed on discharge/charge from the ideal cell reaction O2 + x e− + x M+ ⇄ MxO2 (M=Li, Na, K). We chose the Li–O2 cell to demonstrate the impact of PeDTFSI as a quencher since amongst Li–, Na–, and K–O2 cells, Li–O2 shows the most severe side reactions.1b, 2c,2e, 3a,3b, 11, 14 Li–O2 cells were constructed as detailed in the Supporting Information with carbon black/PTFE cathodes and TEGDME electrolytes containing 1 m LiTFSI, 30 mm DMA and either no quencher, DABCO, or PeDTFSI. Cells were cycled at constant current and the O2 consumption/evolution monitored using a pressure transducer connected to the cell head space. After discharge, the electrolyte was extracted and analysed for the degree of DMA into DMA‐O2 conversion as a measure for unquenched 1O2, and the electrodes were analysed for the amount of Li2O2 and carbonaceous side products using the established procedures of photometry of the [Ti(O2)OH]+ complex and CO2 evolution upon adding acid and Fenton's reagent.15

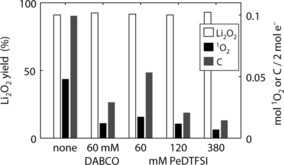

For the first discharge, we ran cells without quencher, with 60 mm DABCO, or 60, 120, or 380 mm PeDTFSI. The e−/O2 ratio was within 2 % of the ideal value of 2 (Figure S12), which is in accord with previous reports for similar cells without quencher.3a,3b, 4a, 11, 15 Li2O2 yields were around 95 to 96 % without a significant trend with regard to the presence of a quencher (white bars in Figure 3). This result is in accord with the expectation that deactivating already formed 1O2 would not be expected to influence the Li2O2 yield, but rather the amount of side products. Consequently, the amount of unquenched 1O2 directly correlates with the amount of carbonaceous side products formed (black and grey bars in Figure 3). Presence of 60 mm DABCO cuts the side products by a factor of 4. The same concentration of PeDTFSI cuts the side products by half in accord with the lower molar quenching efficiency. With 380 mm PeDTFSI, however, the side products were cut to 14 % of the value without quencher. PeDTFSI hence effectively reduces 1O2 related parasitic chemistry on discharge.

Figure 3.

Li2O2 yield, unquenched 1O2 (as obtained from DMA conversion), and total carbonaceous side products (labelled with C) in Super P/PTFE (9/1, m/m) composite electrodes after discharge at 100 mA g gC −1 to 1000 mAh gC −1 in 1 m LiTFSI/TEGDME containing the given quenchers.

Turning to cell charge, we assessed the effect of a quencher on the O2 evolution rate as measured by the pressure in the cell head space. DABCO has already been shown to reduce 1O2 related parasitic chemistry on charge within the limited oxidative stability of 3.6 V.4a We hence focus on the quencher‐free cell in comparison to a cell with electrolyte containing 380 mm PeDTFSI. Cells were first discharged at 100 mA gC −1 to 1000 mAh gC −1 and then recharged to a cut‐off voltage of 4.6 V (Figure 4). For the quencher‐free cell, the voltage rises to within a few percent of the recharge capacity towards a plateau at around 4.2 V before it further rises steeply close to the end of recharge. The O2 evolution remains from the onset of charge, significantly below the value required for 2 e−/O2, indicating e− extraction from side products and the reaction of released O2 species with cell components rather than evolving as O2.3a,3b,3d A similar behaviour has frequently been observed in similar quencher‐free Li–O2 cells.1a, 3a,3b,3d The quickly increasing voltage was partly related to increasingly difficult electron transfer as the Li2O2 decrease on charging,2d, 3c and mainly to the increasing oxidation potential caused by newly formed parasitic products.1a, 3

Figure 4.

a),b) Voltage profiles during recharge of Super P/PTFE (9/1, m/m) composite electrodes after discharge to 1000 mAh gC −1 at 100 mA gC −1 in O2 saturated 1 m LiTFSI/TEGDME without (a) and with 380 mm PeDTFSI (b). c),d) Cumulative O2 evolution in the cells in (a) and (b), respectively, as determined by measuring the pressure in the cell head space in comparison to the theoretical value based on current.

In contrast, the cell with PeDTFSI evolves O2 at the ideal rate of 2 e−/O2 up to approximately 4.2 V, which confirms that a) all the electrons are extracted from Li2O2 rather than partly from side products and b) any 1O2 is quenched to 3O2 rather than forming side products. We have previously shown that Li2O2 oxidation evolves considerable fractions of 1O2 from the onset of charge, causing the O2 evolution rate to be below that expected for 2 e−/O2.4a Since a quencher cannot suppress 1O2 formation, the observed rate of 2 e−/O2 hence means that PeDTFSI effectively quenches 1O2 into 3O2. Together with the much lower amounts of side products at the end of discharge (Figure 3), the eliminated 1O2 on charging also avoids more side products forming on recharging. This is reflected in the slower rise of the voltage compared to the quencher‐free cell. Nevertheless rising voltage can be related to increasingly difficult electron transport from Li2O2 remote from the electrode surface as charging proceeds.2d, 3c That this is the reason for rising voltage is further supported by comparing the amount of oxidized Li2O2 with the charge passed. Charge capacity at cut‐off corresponds to 23 % of the formed Li2O2, which balances with 77 % left as measured by Li2O2 titration. Electron flux overwhelmingly oxidizing Li2O2 further corroborates that rising voltage is not caused by side‐product formation but rather by loss of contact.16 PeDTFSI is amphoteric, Lewis basic at the tertiary N atom and Lewis acidic at the quaternary N atom, which could possibly solubilize the LiO2 intermediate. Difficulties in recharging cells using additives favouring the solution mechanism are widely recognized and similarly the impeded recharge under conditions that favour solution processes have been discussed analogously.1f, 16b, 17 Such cells are now recognized to require mediators for full charge.1f

In conclusion, we show that DABCOnium, the mono alkylated form of the diamine 1,4‐diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (DABCO), is an efficient 1O2 quencher with high voltage stability suitable for non‐aqueous battery cathodes and the Li anode. Quaternizing one of the nitrogen atoms raises the oxidation stability of the remaining tertiary nitrogen from 3.6 V vs. Li/Li+ to approximately 4.2 V. We demonstrate the efficiency of DABCOnium by means of the Li–O2 cathode, where 1O2 related parasitic chemistry is particularly severe and where the quencher greatly reduces the parasitic chemistry. On a wider perspective, partly quaternizing diamines is suitable to tune the oxidation potential of 1O2 quenchers. 1O2 is now also known to evolve from layered transition‐metal cathodes and upon oxidizing Li2CO3, a common impurity of cathode materials. Quenchers stable under high‐voltage are hence relevant to control 1O2 related interfacial reactivity and long‐term cyclability of many currently studied cathodes.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

S.A.F. is indebted to the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement no. 636069). We thank A. Samojlov and D. Schuster for support with measurements. We thank EL‐Cell GmbH (Hamburg, Germany) for the PAT‐Cell‐Press test cells.

Y. K. Petit, C. Leypold, N. Mahne, E. Mourad, L. Schafzahl, C. Slugovc, S. M. Borisov, S. A. Freunberger, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 6535.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Lu Y.-C., Gallant B. M., Kwabi D. G., Harding J. R., Mitchell R. R., Whittingham M. S., Shao-Horn Y., Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 750–768; [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Bender C. L., Hartmann P., Vračar M., Adelhelm P., Janek J., Adv. Energy Mater. 2014, 4, 1301863; [Google Scholar]

- 1c. Croguennec L., Palacin M. R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 3140–3156; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1d. Renfrew S. E., McCloskey B. D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 17853–17860; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1e. Assat G., Tarascon J.-M., Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 373–386; [Google Scholar]

- 1f. Aurbach D., McCloskey B. D., Nazar L. F., Bruce P. G., Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 16128; [Google Scholar]

- 1g. Luo K., Roberts M. R., Hao R., Guerrini N., Pickup D. M., Liu Y.-S., Edström K., Guo J., Chadwick A. V., Duda L. C., Bruce P. G., Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 684–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Ganapathy S., Adams B. D., Stenou G., Anastasaki M. S., Goubitz K., Miao X.-F., Nazar L. F., Wagemaker M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 16335–16344; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Liang Z., Lu Y.-C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 7574–7583; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2c. Liu T., Kim G., Casford M. T. L., Grey C. P., J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 4841–4846; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2d. Wang J., Zhang Y., Guo L., Wang E., Peng Z., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 5201–5205; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 5287–5291; [Google Scholar]

- 2e. Wang W., Lai N.-C., Liang Z., Wang Y., Lu Y.-C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 5042–5046; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 5136–5140. [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. McCloskey B. D., Valery A., Luntz A. C., Gowda S. R., Wallraff G. M., Garcia J. M., Mori T., Krupp L. E., J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 2989–2993; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3b. McCloskey B. D., Bethune D. S., Shelby R. M., Mori T., Scheffler R., Speidel A., Sherwood M., Luntz A. C., J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 3043–3047; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3c. Højberg J., McCloskey B. D., Hjelm J., Vegge T., Johansen K., Norby P., Luntz A. C., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 4039—4047; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3d. McCloskey B. D., Garcia J. M., Luntz A. C., J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 1230–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Mahne N., Schafzahl B., Leypold C., Leypold M., Grumm S., Leitgeb A., Strohmeier G. A., Wilkening M., Fontaine O., Kramer D., Slugovc C., Borisov S. M., Freunberger S. A., Nat. Energy 2017, 2, 17036; [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Schafzahl L., Mahne N., Schafzahl B., Wilkening M., Slugovc C., Borisov S. M., Freunberger S. A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 15728–15732; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 15934–15938; [Google Scholar]

- 4c. Wandt J., Jakes P., Granwehr J., Gasteiger H. A., Eichel R.-A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 6892–6895; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 7006–7009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. Chaisiwamongkhol K., Batchelor-McAuley C., Palgrave R. G., Compton R. G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 6270–6273; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 6378–6381; [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Carboni M., Marrani A. G., Spezia R., Brutti S., J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, A118–A125. [Google Scholar]

- 6.

- 6a. Hatsukade T., Schiele A., Hartmann P., Brezesinski T., Janek J., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 38892–38899; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Wandt J., Freiberg A. T. S., Ogrodnik A., Gasteiger H. A., Mater. Today 2018, 21, 825–833; [Google Scholar]

- 6c. Mahne N., Renfrew S. E., McCloskey B. D., Freunberger S. A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 5529–5533; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 5627–5631. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schweitzer C., Schmidt R., Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 1685–1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Borisov S. M., Nuss G., Haas W., Saf R., Schmuck M., Klimant I., J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2009, 201, 128–135. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miyamoto S., Martinez G. R., Medeiros M. H. G., Di Mascio P., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 6172–6179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wilkinson F., Helman W. P., Ross A. B., J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1995, 24, 663–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Adams B. D., Black R., Williams Z., Fernandes R., Cuisinier M., Berg E. J., Novak P., Murphy G. K., Nazar L. F., Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1400867. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yoshizawa-Fujita M., Johansson K., Newman P., MacFarlane D. R., Forsyth M., Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 2755–2758. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gutmann V., Coord. Chem. Rev. 1976, 18, 225–255. [Google Scholar]

- 14.

- 14a. Black R., Shyamsunder A., Adeli P., Kundu D., Murphy G. K., Nazar L. F., ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 1795–1803; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14b. Sayed S. Y., Yao K. P. C., Kwabi D. G., Batcho T. P., Amanchukwu C. V., Feng S., Thompson C. V., Shao-Horn Y., Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 9691–9694; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14c. Xiao N., Rooney R. T., Gewirth A. A., Wu Y., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 1227–1231; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 1241–1245. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schafzahl B., Mourad E., Schafzahl L., Petit Y. K., Raju A. R., Thotiyl M. O., Wilkening M., Slugovc C., Freunberger S. A., ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 170–176. [Google Scholar]

- 16.

- 16a. Gao X., Chen Y., Johnson L., Bruce P. G., Nat. Mater. 2016, 15, 882; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16b. Gao X., Jovanov Z. P., Chen Y., Johnson L. R., Bruce P. G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 6539–6543; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 6639–6643. [Google Scholar]

- 17.

- 17a. Burke C. M., Pande V., Khetan A., Viswanathan V., McCloskey B. D., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 9293–9298; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17b. Zhang Y., Wang L., Zhang X., Guo L., Wang Y., Peng Z., Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1705571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary