This cohort study compares the risk of developing atrial fibrillation or major adverse cardiovascular events associated with ustekinumab vs a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor therapy among patients with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis.

Key Points

Question

What are the risks of atrial fibrillation and major adverse cardiovascular events associated with the use of ustekinumab compared with the use of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors among patients with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis?

Findings

In this cohort study that included data on 60 028 patients with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis from multiple databases, no significant difference was found in the risk of developing atrial fibrillation or major adverse cardiovascular events after initiation of therapy with ustekinumab vs a TNF inhibitor.

Meaning

The risks of atrial fibrillation and major adverse cardiovascular events associated with the use of ustekinumab vs TNF inhibitors were not different in patients with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis; further investigations on potentially modifying treatment effects stratified by important risk factors may be warranted.

Abstract

Importance

Accumulating evidence indicates that there is an increased risk of cardiovascular disease among patients with psoriatic disease. Although an emerging concern that the risk of atrial fibrillation (AF) may also be higher in this patient population adds to the growing support of initiating early interventions to control systemic inflammation, evidence on the comparative cardiovascular safety of current biologic treatments remains limited.

Objective

To evaluate the risk of AF and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) associated with use of ustekinumab vs tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) in patients with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study included data from a nationwide sample of 78 162 commercially insured patients in 2 US commercial insurance databases (Optum and MarketScan) from September 25, 2009, through September 30, 2015. Patients were included if they were 18 years or older, had psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis, and initiated ustekinumab or a TNFi therapy. Exclusion criteria included history of AF or receipt of antiarrhythmic or anticoagulant therapy during the baseline period.

Exposures

Initiation of ustekinumab vs TNFi therapy.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Incident AF and MACE, including myocardial infarction, stroke, or coronary revascularization.

Results

A total of 60 028 patients with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis (9071 ustekinumab initiators and 50 957 TNFi initiators) were included in the analyses. The mean (SD) age was 46 (13) years in Optum and 47 (13) in MarketScan, and 29 495 (49.1%) were male. Overall crude incidence rates (reported per 1000 person-years) for AF were 5.0 (95% CI, 3.8-6.5) for ustekinumab initiators and 4.7 (95% CI, 4.2-5.2) for TNFi initiators, and for MACE were 6.2 (95% CI, 4.9-7.8) for ustekinumab initiators and 6.1 (95% CI, 5.5-6.7) for TNFi initiators. The combined adjusted hazard ratio for incident AF among ustekinumab initiators was 1.08 (95% CI, 0.76-1.54) and for MACE among ustekinumab initiators was 1.10 (95% CI, 0.80-1.52) compared with TNFi initiators.

Conclusions and Relevance

No substantially different risk of incident AF or MACE after initiation of ustekinumab vs TNFi was observed in this study. This information may be helpful when weighing the risks and benefits of various systemic treatment strategies for psoriatic disease.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is one of the major comorbidities in patients with psoriatic disease.1,2 The epidemiologic evidence indicates that psoriatic disease is an independent risk factor for CVD with a 28% increase in risk of coronary heart disease, 6% to 12% increase in risk of stroke, and 20% increase in risk of a composite end point of myocardial infarction and stroke among patients with psoriatic disease compared with the general population.3,4,5 With several studies reporting that a proinflammatory state in psoriasis is associated with the increased risk of CVD, there is increasing interest in early treatment to reduce systemic inflammation in the early stage of the disease.6,7,8,9 Evidence about the increased risk of atrial fibrillation (AF) in this patient population also has emerged, suggesting an overlapping inflammatory process of the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation and the chronic systemic inflammatory state in psoriasis, which adds to the accumulating support for tight control of chronic inflammation in treating the disease.10,11,12

Making informative decisions on treatment, however, is often hindered by insufficient or conflicting information about comparative effectiveness and safety profiles of available treatment options. Based on the well-established role of proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor–α (TNF-α), in the underlying inflammation, many studies have investigated the potential cardioprotective association of systemic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) with the risk of CVD with an emphasis on the biologic treatment. Although there is increasing evidence that treatment with TNF inhibitors (TNFi) may be associated with a reduced risk of CVD in patients with psoriatic arthritis, data regarding CVD risk associated other biologic treatments have been largely lacking.13,14,15,16 For interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-23 antagonists, the preliminary results from a phase III randomized clinical trial linked briakinumab to an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE)17; however, contradicting results were found from further investigations of IL-12 and IL-23 inhibitors, including ustekinumab,18 and there has been a lack of direct comparisons with other biologic treatments. Thus, the associations between these biologic agents and cardiovascular risk have yet to be determined to date. With an emerging body of evidence about the associations between AF and psoriasis, a direct comparison of the associations of these agents with a broad spectrum of cardiovascular outcomes is imperative.

Thus, we compared the risk of CVD associated with ustekinumab vs TNFi therapy in patients with psoriatic disease. Our focus was on assessing potentially differential cardiovascular risk between ustekinumab and anti-TNF agents, with the primary interest on the association of these agents with developing new-onset AF and MACE.

Methods

Data Sources

We conducted a cohort study using Optum Clinformatics (Optum) and Truven MarketScan (Truven Health Analytics), 2 US commercial health care claims databases, between September 25, 2009, the date ustekinumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and September 30, 2015. Optum and MarketScan contain demographic data and longitudinal claims information, including hospitalizations, outpatient visits, procedures, and pharmacy dispensing, as well as plan information from a number of different managed care plans; these databases are representative of a national commercially insured population in the United States. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. Patient informed consent was not required because the database was deidentified to protect subject confidentiality.

Study Cohort

Patients 18 years or older who had at least 1 visit coded for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] diagnosis code 696.0 or 696.1) who initiated therapy with ustekinumab or a TNFi (ie, adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab, or golimumab) were identified. The cohort entry date (ie, index date) was defined as the date of ustekinumab or TNFi therapy initiation, and treatment initiation was defined as the absence of the pertinent drug exposure within the last 12 months of the index date. All patients were required to have at least 12 months of continuous enrollment before the index date (ie, baseline period) in the health plan. This requirement was to ensure that we identified study patients with at least 1 year of claims history for medical services and prescription dispensing to appropriately identify new users and control for baseline confounding. We excluded patients who had a previous diagnosis of AF (ICD-9-CM diagnosis code 427.3x) or received antiarrhythmic or anticoagulant therapy during the baseline period.

Patients were followed up from the day after the index date until the first occurrence of the following events: outcomes of interest (ie, AF or MACE), death, plan disenrollment, filling a prescription for a drug in the other exposure group, discontinuing treatment with a grace period of 90 days, or end of study period. Patients were allowed to enter the study cohort only once.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes of interest were incident AF and MACE. Incident AF was defined as 1 inpatient visit or at least 2 outpatient visits coded with ICD-9-CM diagnosis code 427.31 or 427.32.19 Major adverse cardiovascular event was a composite cardiovascular event of myocardial infarction, stroke, and coronary revascularization. Myocardial infarction was based on an inpatient diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction (ICD-9-CM diagnosis code 410.x excluding 410.x2) in the primary position.20 Stroke was defined with an inpatient diagnosis of ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes 433.x1, 434.x1, 435.x, and 436.x).21 Coronary revascularization was defined based on a combination of procedure codes. The complete list of codes used to identify these cases is available in eTable 1 in the Supplement.

Covariates

We measured more than 60 predefined variables potentially associated with psoriatic disease severity and cardiovascular risk in each database during the 12-month baseline period. We assessed the cohort entry year; demographic characteristics; comorbid conditions; heath care utilization measures, such as hospital admissions or emergency department visits; and other medication uses. To assess covariates potentially indicative of disease severity, we determined patients’ history of receiving treatment for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis, including UV irradiation and topical and systemic agents. We also calculated the combined comorbidity score based on 47 conditions.22

Statistical Analysis

In each database, we compared the baseline characteristics between ustekinumab and TNFi initiators using standardized differences. An absolute standardized difference of more than 10% indicates substantial imbalance between the 2 groups.23 We calculated the crude incidence rates and 95% CIs for AF and MACE for the exposure groups.

To control for potential confounding, we used propensity score fine stratification and weighting.24 We first estimated propensity scores as the predicted probability of receiving ustekinumab vs TNFi conditional on the covariates mentioned above using a multivariable logistic regression model within each database. We restricted the population to those within the overlapping areas of the propensity score distributions to exclude potentially noncomparable patients and created 50 strata based on the distribution of propensity scores among patients who initiated ustekinumab. Patients in the reference group (ie, TNFi initiators) were weighted proportionally to the distribution of the exposure group among propensity score strata. Balance of baseline characteristics achieved in the weighted population was assessed using standardized differences. The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of each outcome was estimated using a weighted Cox proportional hazards regression model in each database. The database-specific adjusted HRs were combined using an inverse variance–weighted random effects model.

Subgroup analyses were performed by age group (ie, <60 years or ≥60 years), sex, and the presence of preexisting diabetes. To account for confounding in these subgroup analyses, we built the propensity score models and used fine stratification of 50 strata based on the propensity score separately within each subgroup in each database. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Cohort Selection and Patient Characteristics

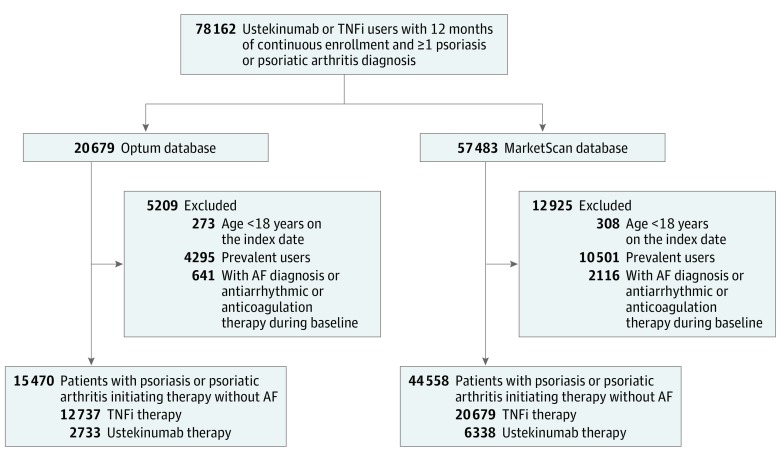

Among 78 162 patients with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis who initiated treatment with either ustekinumab or TNFi identified across the 2 databases, we included 60 028 patients (9071 ustekinumab and 50 957 TNFi initiators; 29 495 [49.1%] male) after applying the exclusion criteria based on patient age, previous use of study treatment, and history of AF (Figure 1). The distributions of baseline characteristics in the 2 treatment groups before propensity score stratification and weighting are shown in eTable 2 in the Supplement. Patients receiving ustekinumab were younger than those receiving TNFi, with a mean (SD) age of 46.0 (12.6) years among those receiving ustekinumab vs 47.3 (13.0) years among those receiving TNFi in the Optum cohort and 46.7 (12.9) years vs 47.3 (12.6) years in the MarketScan cohort. Ustekinumab initiators had a lower proportion of women compared with TNFi initiators (1224 of 2733 [44.8%] vs 6423 of 12 737 [50.4%] in Optum and 2915 of 6338 [46.0%] vs 19 971 of 38 220 [52.2%] in MarketScan). There were substantial differences between the treatment groups in the clinical characteristics associated with psoriatic disease, including a higher proportion of patients with a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis and use of nonbiologic DMARDs and steroids in the TNFi group compared with the ustekinumab group. Patients who initiated ustekinumab therapy were more likely to have had exposure to other biologic DMARDs, UV light, and topical therapies and to have had more inpatient and outpatient visits diagnostically coded with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. Although both treatment groups were similar with regard to cardiovascular comorbidities, comorbidity index, and health care utilization patterns, TNFi initiators had more office visits, greater overall medication use, and more patients using pain medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, and opioids, compared with ustekinumab initiators.

Figure 1. Study Cohort Selection.

AF indicates atrial fibrillation; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

In a total weighted population of 59 735 participants (9066 in the ustekinumab group and 50 669 in the TNFi group) after adjustment by propensity score stratification and weighting, baseline characteristics between the 2 groups were balanced, with a maximum absolute standardized difference of 2% in all covariates (Table 1).

Table 1. Selected Characteristics After Propensity Score Weightinga.

| Variable | Optum | MarketScan | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ustekinumab (n = 2730) | TNFi (n = 12 673) | Standardized Differencesb | Ustekinumab (n = 6336) | TNFi (n = 37 996) | Standardized Differencesb | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 46.0 (12.6) | 46.1 (13.2) | −0.9 | 46.7 (12.9) | 46.8 (13.0) | −0.4 |

| Female | 1224 (44.8) | 5775 (45.6) | −1.5 | 2914 (46) | 17 549 (46.2) | −0.4 |

| Psoriasis diagnosis | 536 (19.6) | 2320 (18.3) | 3.4 | 1212 (19.1) | 7093 (18.7) | 1.2 |

| Psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis diagnosis, mean (SD), No. of clinic visits | 6.8 (9.5) | 6.7 (10.7) | 1.1 | 6.9 (9.8) | 7.0 (12.0) | −1.1 |

| Treatment | ||||||

| UV irradiation | 249 (9.1) | 1156 (9.1) | 0.0 | 579 (9.1) | 3604 (9.5) | −1.2 |

| Topical therapy | 2059 (75.4) | 9603 (75.8) | −0.8 | 4526 (71.4) | 27 425 (72.2) | −1.7 |

| Nonbiologic DMARD | 709 (26.0) | 3240 (25.6) | 0.9 | 1595 (25.2) | 9457 (24.9) | 0.7 |

| Biologic DMARDc | 1169 (42.8) | 5215 (41.1) | 3.4 | 2693 (42.5) | 15 697 (41.3) | 2.4 |

| Cumulative oral steroids, mean (SD)d | 4.3 (12.9) | 4.3 (12.8) | 0.0 | 4.3 (14.2) | 4.3 (13.6) | 0.2 |

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Diabetes | 351 (12.9) | 1653 (13.0) | −0.6 | 961 (15.2) | 5741 (15.1) | 0.2 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 925 (33.9) | 4340 (34.2) | −0.8 | 1924 (30.4) | 11 606 (30.5) | −0.4 |

| Hypertension | 854 (31.3) | 4006 (31.6) | −0.7 | 1996 (31.5) | 12 047 (31.7) | −0.4 |

| Heart failure | 33 (1.2) | 159 (1.3) | −0.4 | 72 (1.1) | 426 (1.1) | 0.1 |

| Coronary heart disease | 120 (4.4) | 550 (4.3) | 0.3 | 300 (4.7) | 1803 (4.7) | −0.1 |

| Stroke or transient ischemic attack | 28 (1.0) | 124 (1.0) | 0.5 | 46 (0.7) | 282 (0.7) | −0.2 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 34 (1.2) | 161 (1.3) | −0.3 | 77 (1.2) | 446 (1.2) | 0.4 |

| Thromboembolism | 6 (0.2) | 22 (0.2) | 1.0 | 28 (0.4) | 183 (0.5) | −0.6 |

| Obesity | 317 (11.6) | 1476 (11.6) | −0.1 | 548 (8.6) | 3304 (8.7) | −0.2 |

| Tobacco use | 217 (7.9) | 999 (7.9) | 0.3 | 349 (5.5) | 2129 (5.6) | −0.4 |

| Alcohol abuse | 50 (1.8) | 214 (1.7) | 1.1 | 54 (0.9) | 351 (0.9) | −0.8 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 32 (1.2) | 156 (1.2) | −0.5 | 94 (1.5) | 622 (1.6) | −1.2 |

| Asthma | 162 (5.9) | 754 (5.9) | −0.1 | 279 (4.4) | 1686 (4.4) | −0.2 |

| COPD | 135 (4.9) | 649 (5.1) | −0.8 | 277 (4.4) | 1666 (4.4) | −0.1 |

| Depression | 374 (13.7) | 1703 (13.4) | 0.8 | 710 (11.2) | 4277 (11.3) | −0.2 |

| Chronic liver disease | 165 (6.0) | 750 (5.9) | 0.5 | 322 (5.1) | 1966 (5.2) | −0.4 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 57 (2.1) | 279 (2.2) | −0.8 | 92 (1.5) | 575 (1.5) | −0.5 |

| Long-term corticosteroid use | 20 (0.7) | 94 (0.7) | −0.1 | 24 (0.4) | 152 (0.4) | −0.3 |

| Long-term opioid use | 1526 (55.9) | 7100 (56) | −0.3 | 2802 (44.2) | 16 827 (44.3) | −0.1 |

| Combined comorbidity score, mean (SD) | 0.2 (1.1) | 0.2 (1.1) | 0.3 | 0.1 (1.0) | 0.1 (1.0) | −0.6 |

| Medication use | ||||||

| Noninsulin antidiabetic | 261 (9.6) | 1246 (9.8) | −0.9 | 679 (10.7) | 4089 (10.8) | −0.1 |

| Insulin | 108 (4.0) | 540 (4.3) | −1.5 | 233 (3.7) | 1402 (3.7) | −0.1 |

| β-Blocker | 276 (10.1) | 1289 (10.2) | −0.2 | 666 (10.5) | 4007 (10.5) | −0.1 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 237 (8.7) | 1108 (8.7) | −0.2 | 547 (8.6) | 3278 (8.6) | 0.0 |

| ACEI or ARB | 598 (21.9) | 2827 (22.3) | −1.0 | 1490 (23.5) | 8981 (23.6) | −0.3 |

| Diuretic | 447 (16.4) | 2128 (16.8) | −1.1 | 1097 (17.3) | 6638 (17.5) | −0.4 |

| Lipid lowering | 630 (23.1) | 2983 (23.5) | −1.1 | 1472 (23.2) | 8881 (23.4) | −0.3 |

| Antiplatelet | 53 (1.9) | 245 (1.9) | 0.1 | 151 (2.4) | 874 (2.3) | 0.5 |

| NSAID | 616 (22.6) | 2806 (22.1) | 1.0 | 1522 (24.0) | 8920 (23.5) | 1.3 |

| Health care utilization measures | ||||||

| Office visits, mean (SD), No. | 8.4 (6.4) | 8.3 (6.2) | 0.8 | 8.7 (6.4) | 8.8 (6.9) | −0.2 |

| Visits to emergency department | 326 (11.9) | 1520 (12) | −0.2 | 1188 (18.8) | 7103 (18.7) | 0.1 |

| Hospital admissions | 163 (6.0) | 736 (5.8) | 0.7 | 384 (6.1) | 2289 (6) | 0.1 |

| Hospital admissions, mean (SD), No. | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.1 (0.4) | 1.1 | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.0 |

| Unique medications, mean (SD), No. | 9.5 (6.3) | 9.6 (6.1) | −0.5 | 9.3 (6.5) | 9.3 (6.1) | −0.2 |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; NSAID, nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Values are presented as number (percentage) of individuals unless otherwise specified.

A standardized difference of 10% denotes a meaningful imbalance in the covariates between the 2 treatment groups (23).

Biologic DMARD other than the index drug dispensed during the baseline period.

Prednisone-equivalent dose in milligrams.

Risk of Incident AF

During a mean (SD) follow-up of 1.4 (1.3) years with a maximum observation period of 6.0 years, 383 diagnoses of incident AF (60 in ustekinumab initiators and 323 in TNFi initiators) were observed in the study cohort (Table 2). The overall crude incidence rates (IRs) (reported per 1000 person-years) for AF were 5.0 (95% CI, 3.8-6.5) in ustekinumab initiators and 4.7 (95% CI, 4.2-5.2) in TNFi initiators. The database-specific IRs for AF were 5.0 (95% CI, 3.0-7.9) in the ustekinumab group and 4.1 (95% CI, 3.2-5.1) in the TNFi group in the Optum cohort and 5.0 (95% CI, 3.7-6.7) in the ustekinumab group and 4.9 (95% CI, 4.3-5.5) in the TNFi group in the MarketScan cohort. The adjusted HR of incident AF for use of ustekinumab compared with TNFi was 1.40 (95% CI, 0.81-2.41) in the Optum database and 0.95 (95% CI, 0.69-1.32) in the MarketScan database, with a combined HR of 1.08 (95% CI, 0.76-1.54) (Table 3).

Table 2. Relative Risk of Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Treated With Ustekinumab vs TNFi.

| Outcome, Data Source | Ustekinumab | TNFi | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, No. | Events, No. | Person-Years, No. | IR per 1000 Person-Years (95% CI) | IR Ratio (95% CI) | Patients, No. | Events, No. | Person-Years, No. | IR per 1000 Person-Years (95% CI) | IR Ratio | |

| Unadjusted | ||||||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | ||||||||||

| Optum | 2733 | 17 | 3382 | 5.0 (3.0-7.9) | 1.24 (0.73-2.11) | 12 737 | 68 | 16 806 | 4.1 (3.2-5.1) | 1 [Reference] |

| MarketScan | 6338 | 43 | 8545 | 5.0 (3.7-6.7) | 1.03 (0.75-1.43) | 38 220 | 255 | 52 514 | 4.9 (4.3-5.5) | 1 [Reference] |

| MACEa | ||||||||||

| Optum | 2733 | 13 | 3397 | 3.8 (2.1-6.4) | 0.71 (0.40-1.27) | 12 737 | 90 | 16 748 | 5.4 (4.3-6.6) | 1 [Reference] |

| MarketScan | 6338 | 61 | 8531 | 7.2 (5.5-9.1) | 1.13 (0.86-1.49) | 38 220 | 331 | 52 435 | 6.3 (5.7-7.0) | 1 [Reference] |

| Adjusted for Propensity Score | ||||||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | ||||||||||

| Optum | 2730 | 17 | 3379 | 5.0 (3.0-7.9) | 1.40 (0.81-2.41) | 12 673 | 55 | 15 272 | 3.6 (2.7-4.7) | 1 [Reference] |

| MarketScan | 6336 | 43 | 8545 | 5.0 (3.7-6.7) | 0.96 (0.70-1.33) | 37 996 | 258 | 49 268 | 5.2 (4.6-5.9) | 1 [Reference] |

| MACEa | ||||||||||

| Optum | 2730 | 13 | 3393 | 3.8 (2.2-6.4) | 0.83 (0.46-1.51) | 12 673 | 70 | 15 228 | 4.6 (3.6-5.8) | 1 [Reference] |

| MarketScan | 6336 | 61 | 8531 | 7.2 (5.5-9.1) | 1.22 (0.92-1.61) | 37 996 | 289 | 49 229 | 5.9 (5.2-6.6) | 1 [Reference] |

Abbreviations: IR, incidence rate; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

Composite cardiovascular event of myocardial infarction, stroke, and coronary revascularization.

Table 3. Adjusted Risk of Atrial Fibrillation and a Composite Cardiovascular Event in Patients With Psoriatic Disease Initiating Ustekinumab vs TNFi Therapya.

| Outcome, Data Source | HR (95% CI) | Combinedb | Heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2, % | P Valuec | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | ||||

| Optum | 1.40 (0.81-2.41) | 1.08 (0.76-1.54) | 29.0 | .24 |

| MarketScan | 0.95 (0.69-1.32) | |||

| MACEd | ||||

| Optum | 0.83 (0.46-1.50) | 1.10 (0.80-1.52) | 21.5 | .26 |

| MarketScan | 1.21 (0.92-1.59) | |||

Abbreviations: HR, hazard rate; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

Adjusted for the variables listed in eTable 1 in the Supplement using propensity-score stratification.

Combined using an inverse variance–weighted, random effects model.

P value of Q test for heterogeneity.

Composite cardiovascular event of myocardial infarction, stroke, and coronary revascularization.

Risk of MACE

For MACE, a total of 495 cases (74 in the ustekinumab group and 421 in the TNFi group) were observed during the follow-up, and the overall crude IRs were 6.2 (95% CI, 4.9-7.8) among ustekinumab initiators and 6.1 (95% CI, 5.5-6.7) among TNFi initiators. For the Optum cohort, the crude IRs were 3.8 (95% CI, 2.1-6.4) in the ustekinumab group and 5.4 (95% CI, 4.3-6.6) in the TNFi group; crude IRs in the MarketScan were 7.2 (95% CI, 5.5-9.1) in the ustekinumab group and 6.3 (95% CI, 5.7-7.0) in the TNFi group. The adjusted HR associated with ustekinumab vs TNFi was 0.83 (95% CI, 0.46-1.50) in the Optum cohort and 1.21 (95% CI, 0.92-1.59) in the MarketScan cohort, with a combined HR of 1.10 (95% CI, 0.80-1.52).

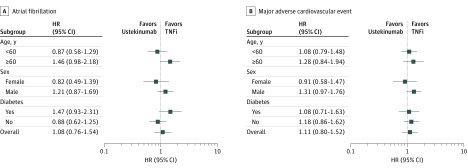

Subgroup Analyses

Figure 2 summarizes the results from subgroup analyses. Overall, there was no statistically significant heterogeneity in the risk of AF and MACE across the subgroups included in the study. For use of ustekinumab vs TNFi in a subgroup of patients 60 years or older, the combined adjusted HR of incident AF in patients was 1.46 (95% CI, 0.98-2.18); in patients with diabetes, the HR was 1.47 (95% CI, 0.93-2.31). The combined adjusted HR of incident AF in men was 1.21 (95% CI, 0.87-1.69), and it was 0.82 (95% CI, 0.49-1.39) in women. The combined adjusted HR of MACE associated with ustekinumab vs TNFi in men was 1.31 (95% CI, 0.97-1.76), and the HR in women was 0.91 (95% CI, 0.56-1.47).

Figure 2. Hazard Ratios for Atrial Fibrillation and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events Among Patient Subgroups Based on Age, Sex, and Diabetes.

Discussion

In this large cohort study of 60 028 patients with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis, we found no overall differential risk of incident AF and a composite cardiovascular end point of myocardial infarction, stroke, and coronary revascularization associated with use of ustekinumab (IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor) vs a TNFi. Furthermore, these risks did not appear to substantially differ across the subgroups included in our study.

Our findings have important clinical implications. The results from this observational study support previous findings of no substantial difference in cardiovascular risk associated with the use of different biologic therapies. Although data on direct comparisons of biologic therapies are lacking, a meta-analysis involving 38 randomized clinical trials25 of biologics in patients with psoriasis reported overall nondifferential risk of MACE associated with TNFi use of 0.05% vs 0.07% with ustekinumab use. Similarly, another meta-analysis of 22 randomized clinical trials reported a slightly increased but nonsignificant risk associated with ustekinumab, with a risk difference of 0.012 cases per person-year (95% CI, −0.001 to 0.026) compared with placebo, and −0.0005 cases per person-year (95% CI, −0.010 to 0.009) with TNFi compared with placebo.26 Although our findings are consistent with the previous observations of a small but nonsignificant increase in CVD among patients with psoriatic disease, our results further provide an insight into the associations of the 2 therapies with the risk of AF in this patient population that appear to be similar. Although further studies are needed, recent evidence on the potential anti-inflammatory property of ustekinumab may provide a partial explanation for lack of differential cardiovascular risk observed with these agents.27 Although we did not observe statistically significant heterogeneity in the treatment associations in the subgroups included in the study, our subgroup analyses were performed based on an a priori decision. Our findings may serve as a hypothesis-generating basis for future studies assessing the differential effects of these treatments, given a growing body of evidence indicating potentially modified treatment effects of biologic agents, by varying patient characteristics to identify important treatment heterogeneity across clinically important subpopulations.28

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has several strengths. The results of this study are based on a large sample size including a diverse patient population with psoriatic disease potentially at different levels of disease severity, reflecting a real-world practice setting, leading to greater generalizability, and allowing performance of additional stratified analyses. Also, using information captured from longitudinal data on patients’ medical conditions and prescription claims, we were able to adjust for a broad range of potential confounding factors. The internal validity of the results was further strengthened by our rigorous methodologic approaches, including the active-comparator, new-user study design, and propensity score fine stratification, which has been shown to control for confounding more efficiently than matching or the coarse stratification approach, especially when the exposure is infrequent.24

This study also has some limitations. First, as is true in any observational study, this study is subject to residual confounding by unmeasured or incompletely measured confounders. Potential confounding by disease severity involving a comparison between novel and conventional agents is a major concern, especially when there exists a disease severity–dependent risk of the outcome. Given the nature of the claims data, we had no data on the severity or duration of psoriatic disease or systemic inflammation. However, we adjusted for several variables (eg, number of clinic visits with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis and previous use of systemic treatment) as potential proxies of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis severity to minimize any potential residual confounding. We also used a new-user design in which both groups had a clinical reason to initiate a new biologic agent, implying the presence of an active disease at the index date.

Second, the follow-up time was relatively short, with a mean of less than 1.5 years, although some patients were followed up for 6 years. Because ustekinumab has only been available in the United States since late 2009, further research with long-term follow-up is needed to assess the long-term safety of these treatments. Third, because the outcomes were ascertained based on diagnosis and procedure codes in claims data, outcome misclassification was possible. However, previous studies showed that the claims-based algorithm to identify AF and CVD had a positive predictive value of 70% to 94%.20,21 Fourth, although the study size was, to our knowledge, the largest to directly compare DMARD treatments in managing psoriatic disease, we may not have had an adequate statistical power for some of the subgroup analyses. Last, although overlapping at the individual health plan level is expected to be minimal across different health plans contributing information to the 2 databases, duplicate patient records may exist across the databases, especially given that both of the databases include commercially insured patients. Although the proportion of those potential duplicates in a previously published study of 2 large commercial insurance databases was estimated to be small, suggesting potentially minimal outcomes on the CIs but not on the point estimates, this is an important issue that may warrant further investigations.29,30

Conclusions

This study found no difference in the risk of developing incident AF or MACE associated with ustekinumab vs TNFi therapy in patients with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. Although the risk of these cardiovascular outcomes appeared to be similar across the subpopulations included in our study, further investigations on potentially modifying treatment effects stratified by important risk factors may be warranted.

eTable 1. Procedure Codes Used to Define Coronary Revascularization Outcome

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics Before Propensity Score Weighting

References

- 1.Jamnitski A, Symmons D, Peters MJ, Sattar N, McInnes I, Nurmohamed MT. Cardiovascular comorbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis [published correction appears in Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(3):467]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(2):211-216. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogdie A, Yu Y, Haynes K, et al. Risk of major cardiovascular events in patients with psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(2):326-332. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimball AB, Guerin A, Latremouille-Viau D, et al. Coronary heart disease and stroke risk in patients with psoriasis. Am J Med. 2010;123(4):350-357. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(10):2411-2418. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu T, Zhang YH. Association of psoriasis with stroke and myocardial infarction. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(6):1345-1350. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frers RAK, Bisoendial RJ, Montoya SF, et al. Psoriasis and cardiovascular risk. IJC Metab Endocr. 2015;6:43-54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcme.2015.01.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernández-Gutiérrez B, Perrotti PP, Gisbert JP, et al. ; IMID Consortium . Cardiovascular disease in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(26):e7308. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gossec L, Smolen JS, Ramiro S, et al. European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(3):499-510. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coates LC, Moverley AR, McParland L, et al. Effect of tight control of inflammation in early psoriatic arthritis (TICOPA). Lancet. 2015;386(10012):2489-2498. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00347-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Jørgensen CH, et al. Psoriasis and risk of atrial fibrillation and ischaemic stroke. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(16):2054-2064. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Upala S, Shahnawaz A, Sanguankeo A. Psoriasis increases risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;28(5):406-410. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2016.1255703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bang CN, Okin PM, Køber L, Wachtell K, Gottlieb AB, Devereux RB. Psoriasis is associated with subsequent atrial fibrillation in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy. J Hypertens. 2014;32(3):667-672. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angel K, Provan SA, Gulseth HL, Mowinckel P, Kvien TK, Atar D. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists improve aortic stiffness in patients with inflammatory arthropathies. Hypertension. 2010;55(2):333-338. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.143982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hugh J, Van Voorhees AS, Nijhawan RI, et al. From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: the risk of cardiovascular disease in individuals with psoriasis and the potential impact of current therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(1):168-177. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu JJ, Poon KY, Channual JC, Shen AY. Association between tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy and myocardial infarction risk in patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(11):1244-1250. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.2502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu JJ, Joshi AA, Reddy SP, et al. Anti-inflammatory therapy with tumour necrosis factor inhibitors is associated with reduced risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(8). doi: 10.1111/jdv.14951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon KB, Langley RG, Gottlieb AB, et al. A phase III, randomized, controlled trial of the fully human IL-12/23 mAb briakinumab in moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(2):304-314. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reich K, Papp KA, Griffiths CE, et al. ; PHOENIX 1, PHOENIX 2, and ACCEPT investigators . An update on the long-term safety experience of ustekinumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(3):300-312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walkey AJ, Greiner MA, Heckbert SR, et al. Atrial fibrillation among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with sepsis: incidence and risk factors. Am Heart J. 2013;165(6):949-955.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.03.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiyota Y, Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ, Cannuscio CC, Avorn J, Solomon DH. Accuracy of Medicare claims-based diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2004;148(1):99-104. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andrade SE, Harrold LR, Tjia J, et al. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attack using administrative data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(suppl 1):100-128. doi: 10.1002/pds.2312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gagne JJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Levin R, Schneeweiss S. A combined comorbidity score predicted mortality in elderly patients better than existing scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(7):749-759. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Austin PC. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Stat Simul Comput. 2009;38(6):1228-1234. doi: 10.1080/03610910902859574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Desai RJ, Rothman KJ, Bateman BT, Hernandez-Diaz S, Huybrechts KF. A propensity-score–based fine stratification approach for confounding adjustment when exposure is infrequent. Epidemiology. 2017;28(2):249-257. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rungapiromnan W, Yiu ZZN, Warren RB, Griffiths CEM, Ashcroft DM. Impact of biologic therapies on risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(4):890-901. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan C, Leonardi CL, Krueger JG, et al. Association between biologic therapies for chronic plaque psoriasis and cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2011;306(8):864-871. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim B-S, Lee W-K, Pak K, et al. Ustekinumab treatment is associated with decreased systemic and vascular inflammation in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;S0190-9622(18)30461-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karczewski J, Poniedziałek B, Rzymski P, Adamski Z. Factors affecting response to biologic treatment in psoriasis. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27(6):323-330. doi: 10.1111/dth.12160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Broder MS, Neary MP, Chang E, Cherepanov D, Katznelson L. Treatments, complications, and healthcare utilization associated with acromegaly. Pituitary. 2014;17(4):333-341. doi: 10.1007/s11102-013-0506-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim SC, Solomon DH, Rogers JR, et al. Cardiovascular safety of tocilizumab versus tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(6):1154-1164. doi: 10.1002/art.40084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Procedure Codes Used to Define Coronary Revascularization Outcome

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics Before Propensity Score Weighting