Abstract

This study uses US National Center for Health Statistics data to describe trends in mortality due to aortic stenosis between 2008 and 2017, when use of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) in older adults was becoming more common.

Symptomatic severe aortic stenosis is associated with high mortality rates, up to 50% at 1 year,1 and the prevalence will likely increase as the population ages.2 Until recently, surgical valve replacement was the only durable therapeutic option; however, many older patients with aortic stenosis have prohibitive surgical risk. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has emerged as an option for these patients and, more recently, for patients with high and moderate surgical risk. We identified trends in mortality due to aortic stenosis, considering these recent therapeutic advances.

Methods

Using the Multiple Cause of Death Data maintained by the US National Center for Health Statistics from 2008 through 2017, we identified patients aged 45 years or older who died of aortic stenosis (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision codes I06.0, I06.2, I35.0, I35.20) listed as the underlying cause of death. Age-adjusted rates (standardized to 2000 US census) are reported per 1 million persons. Subgroup analyses were performed by age groups (<80 vs ≥80 years), sex (male vs female), race/ethnicity (white, black, or Hispanic, as designated on death certificates), and urbanization (metropolitan vs nonmetropolitan, according to the 2013 Urban-Rural Scheme for Counties) to assess for mortality disparities. Trends in mortality due to aortic stenosis were tested using Joinpoint Regression Program 4.7.0.0,3 with a 2-sided P<.05 considered statistically significant. Annual percentage change (APC) is reported for each subgroup with 95% CI. University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center determined this study exempt from review.

Results

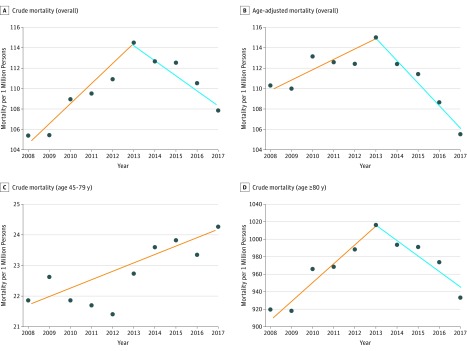

A total of 139 229 deaths due to aortic stenosis were identified during the study period, with 89.2% occurring in patients aged 75 years or older and 59.6% in women. Overall crude and age-adjusted mortality rates were 109.9 and 111.2 per 1 million persons, respectively. The crude mortality rate was highest in the older population: 238.8 and 1535.8 per 1 million persons in patients aged 75 through 84 and 85 years or older, respectively. Age-adjusted mortality increased from 110.2 in 2008 to 115 per 1 million persons in 2013 (APC, 0.9 [95% CI, 0.1-1.6]), followed by a decline to 105.5 per 1 million persons in 2017 (APC, −1.9 [95% CI, −2.9 to −0.9]) (Figure). Between 2014 and 2017, the observed number of deaths due to aortic stenosis was 3938 lower than expected from trend of 2008-2013.

Figure. Mortality Due to Aortic Stenosis, United States, 2008-2017.

The orange lines reflect increasing trends and blue lines reflect decreasing trends. The dots plot observed trends in mortality due to aortic stenosis.

Mortality due to aortic stenosis increased between 2008 and 2017 among people aged 45 through 79 years (APC, 1.2 [95% CI, 0.5-1.9]). Among persons aged 80 years or older, mortality increased from 919.0 in 2008 to 1015.7 per 1 million persons in 2013 (APC, 2.17 [95% CI, 1.03-3.32]), followed by a decrease to 932.9 per 1 million persons in 2017 (APC, −1.77 [95% CI, −3.25 to −0.27]).

Among non-Hispanic white patients, age-adjusted mortality due to aortic stenosis increased between 2008 and 2013 (APC, 1.24 [95% CI, 0.43-2.05]) followed by a decrease until 2017 (APC, −1.58 [95% CI, −2.64 to −0.51). Age-adjusted aortic stenosis mortality was stable in metropolitan areas between 2008 and 2013 and decreased thereafter. There was no change among the non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and nonmetropolitan populations between 2008 and 2017 (Table).

Table. Annual Percentage Change in Aortic Stenosis Mortality Among Subgroups.

| Annual Percentage Change (95% CI), Slope 1 | P Value for Trend | Annual Percentage Change (95% CI), Slope 2 | P Value for Trend | P Value (Slope 1 vs Slope 2) | Joinpoint Year (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (age-adjusted)a | 0.86 (0.11 to 1.61) | .03 | −1.90 (−2.88 to −0.91) | .004 | .002 | 2013 (2012-2015) |

| All (crude)b | 1.76 (1.08 to 2.43) | .001 | −1.18 (−2.06 to −0.30) | .02 | .001 | 2013 (2012-2015) |

| Age, yb | ||||||

| <80 | 1.18 (0.47 to 1.9) | .005 | ||||

| ≥80 | 2.17 (1.03 to 3.32) | .004 | −1.77 (−3.25 to −0.27) | .03 | .003 | 2013 (2012-2015) |

| Sexa | ||||||

| Male | 1.33 (0.45 to 2.22) | .01 | −2.61 (−3.73 to −1.48) | .002 | .001 | 2013 (2012-2014) |

| Female | 0.56 (−0.39 to 1.52) | .19 | −1.59 (−2.85 to −0.31) | .02 | .02 | 2013 (2011-2015) |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1.24 (0.43 to 2.05) | .01 | −1.58 (−2.64 to −0.51) | .01 | .003 | 2013 (2012-2015) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.20 (−0.85 to 1.26) | .67 | ||||

| Hispanic | −0.41 (−1.94 to 1.14) | .56 | ||||

| Urbanizationa,c | ||||||

| Metropolitan area | 0.63 (−0.17 to 1.44) | .10 | −2.02 (−3.07 to −0.96) | .005 | .004 | 2013 (2012-2015) |

| Nonmetropolitan area | 1.18 (0.47 to 1.90) | .005 |

Age-adjusted mortality.

Crude mortality.

According to 2013 National Center for Health Statistics Urban-Rural Scheme for Counties.

Discussion

These results demonstrate a decreasing rate of mortality due to aortic stenosis since 2013 in the older US population. The number of TAVR procedures increased from 4627 in 2012 to almost 35 000 in 2016,4 suggesting that the observed mortality trends may be related to TAVR, especially because there were no other major advances in aortic stenosis therapy during this time, including a relative stabilization of surgical valve replacements.4 The mortality increase prior to 2013 may be a result of improved disease detection. However, despite a temporal association between decreasing mortality due to aortic stenosis and increasing TAVR, a causal relationship cannot be inferred.

Mortality due to aortic stenosis did not decline in the non-Hispanic black or Hispanic populations as it did in non-Hispanic white patients, perhaps as a result of lower prevalence of aortic stenosis.5 However, mortality also did not decline in the nonmetropolitan population as it did in the metropolitan population. Additional attention is warranted to ensure equitable access to advanced technologies such as TAVR.

This study is limited by the lack of information on performed procedures and subjective assessment of cause of death.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. ; PARTNER Trial Investigators . Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(17):1597-1607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coffey S, d’Arcy JL, Loudon MA, Mant D, Farmer AJ, Prendergast BD; OxVALVE-PCS Group . The OxVALVE population cohort study (OxVALVE-PCS)—population screening for undiagnosed valvular heart disease in the elderly: study design and objectives. Open Heart. 2014;1(1):e000043. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2014-000043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335-351. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Agostino RS, Jacobs JP, Badhwar V, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database: 2018 update on outcomes and quality. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;105(1):15-23. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.10.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel DK, Green KD, Fudim M, Harrell FE, Wang TJ, Robbins MA. Racial differences in the prevalence of severe aortic stenosis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(3):e000879. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.000879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]