Abstract

This cohort study uses electronic medical record (EMR) data to examine the association between maternal hemoglobin A1c levels during pregnancy and risk of autism spectrum disorder in offspring.

Maternal preexisting type 1, type 2, or gestational diabetes diagnosed relatively early in pregnancy are associated with increased risk for autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) in offspring.1,2 This study extends previous observations by examining the association between maternal hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels during pregnancy and risk of ASD in offspring.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study included singleton children born at 28 to 44 weeks’ gestation in Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) hospitals between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2013. KPSC implemented HbA1c screening in the early prenatal period for all pregnancies starting in 2012. Children who enrolled as KPSC health plan members at age 1 year were tracked through electronic medical records until the first of the following: (1) clinical diagnosis of ASD with at least 1 diagnostic code, (2) last date of continuous KPSC membership, (3) death, or (4) study end date of December 31, 2017. The KPSC institutional review board approved this study and provided waiver of participant consent.

The last HbA1c level in the first 2 trimesters of pregnancy was obtained from the electronic laboratory database. HbA1c was analyzed as a continuous variable and a categorical variable classified as less than 5.7%, 5.7% to 5.9%, 6.0% to 6.5%, and greater than 6.5%. Methods to identify ASD were previously described.1,2 Cox regression was used to estimate hazard ratios of ASD associated with HbA1c exposure. Kaplan-Meier plots were used to display the crude cumulative incidences of ASD by the HbA1c categories. Potential confounders listed in the Table footnote “a” were evaluated. Interaction with gestational age at HbA1c testing was also assessed. SAS Enterprise Guide version 7.1 (SAS Institute Inc) was used for data analysis. A 2-sided P < .05 was considered significant.

Table. Risk of ASD in Offspring Associated With Maternal HbA1c Levels in Early Pregnancya.

| HbA1c | ASD Cases/Total Children, No. (%) | Unadjusted Hazard Ratios (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted Hazard Ratios (95% CI)b | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As a continuous variable (per 1% increase) | 1.23 (1.08-1.41) | .002 | 1.12 (0.96-1.31) | .15 | |

| As a categorical variablec | |||||

| <5.7% | 574/30 419 (1.89) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| 5.7%-5.9% | 101/4172 (2.42) | 1.24 (1.01-1.54) | .04 | 1.08 (0.87-1.35) | .46 |

| 6.0%-6.5% | 17/871 (1.95) | 0.98 (0.61-1.59) | .94 | 0.79 (0.48-1.28) | .33 |

| >6.5% | 15/357 (4.20) | 2.17 (1.30-3.62) | .003 | 1.79 (1.06-3.00) | .03 |

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder (includes autistic disorders, Asperger syndrome, or pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified); GD, gestational diabetes; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; T1D, preexisting type 1 diabetes; T2D, preexisting type 2 diabetes.

The median gestational age at HbA1c testing was 9.0 weeks (interquartile range, 6.7-11.4 weeks); 83% of the testing was in the first trimester. Potential confounders assessed included maternal age at delivery, prepregnancy body mass index, parity, education, self-reported race/ethnicity; gestational age at HbA1c testing; presence of comorbidity (diagnosis of heart, lung, kidney, or liver disease or cancer) prior to pregnancy; presence of anemia or hemoglobinopathies, smoking, preeclampsia/eclampsia, depression, use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy; and child’s sex. None of them changed the model estimates by more than 10% except for maternal prepregnancy body mass index and race/ethnicity.

Estimated by Cox regression models adjusted for maternal race/ethnicity and prepregnancy body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

Distribution of diabetes status: overall: 0.4% T1D, 5.7% T2D, 9.3% GD, and 84.6% no diabetes; for HbA1c greater than 6.5%: 19.9% T1D, 70.6% T2D, 8.1% GD, and 1.4% no diabetes; for HbA1c between 6.0% and 6.5%: 2.6% T1D, 37.3% T2D, 31.3% GD, and 28.7% no diabetes; for HbA1c between 5.7% and 5.9%: 0.3% T1D, 14.2% T2D, 17.4% GD, and 68.1% no diabetes; and for HbA1c less than 5.7%: 0.1% T1D, 2.8% T2D, 7.6% GD, and 89.5% no diabetes.

Results

A total of 35 819 mother-infant pairs (51% boys) met the study criteria with complete HbA1c and covariate information. The maternal mean (SD) age was 30.9 (5.6) years; the mean (SD) prepregnancy body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) was 27.2 (6.4); and 51% were Hispanic, 24%, white, 7%, black, 14%, Asian/Pacific Islander, and 3%, other. The median gestational age at HbA1c testing was 9.0 weeks (interquartile range, 6.7-11.4 weeks); 83% of the testing was in the first trimester. The median HbA1c level was 5.4% (interquartile range, 5.2%-5.6%); 84.9% of pregnancies had HbA1c levels less than 5.7%, 11.7% between 5.7% and 5.9%, 2.4% between 6.0% and 6.5%, and 1% greater than 6.5%. A total of 99% of women with HbA1c levels greater than 6.5% had diabetes during pregnancy (Table footnote “c”).

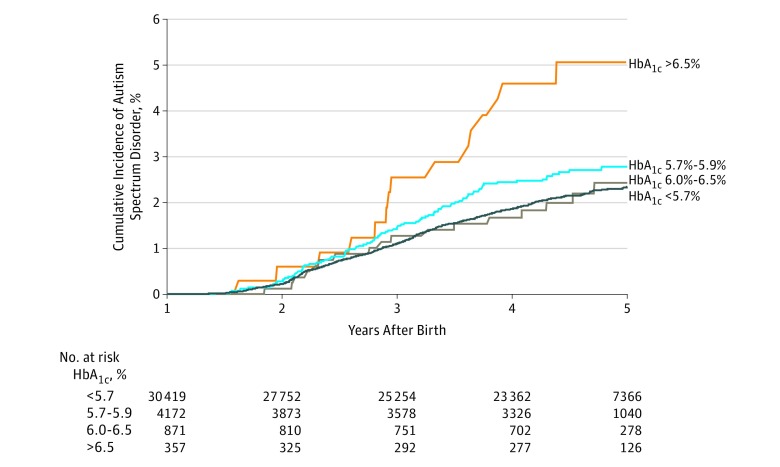

Children were followed up for a median of 4.5 years (interquartile range, 4.0-5.0 years) after birth, during which time 707 (2.0%) had a clinical diagnosis of ASD. In the multivariable analysis, none of the potential confounders changed the model estimates by more than 10% except for maternal prepregnancy body mass index and race/ethnicity. After adjusting for these variables, the hazard ratio of ASD associated with each 1% increase of HbA1c level was 1.12 (95% CI, 0.96-1.31; P = .15) for the continuous measure and 1.08 (95% CI, 0.87-1.35; P = .46) for HbA1c level between 5.7% and 5.9%, 0.79 (95% CI, 0.48-1.28; P = .33) for HbA1c level between 6.0% and 6.5%, and 1.79 (95% CI, 1.06-3.00; P = .03) for HbA1c level greater than 6.5% relative to HbA1c level less than 5.7% (Table; Figure). The risk associated with HbA1c levels did not vary by gestational age at HbA1c testing (P > .19 for interaction).

Figure. Crude Cumulative Incidences of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Offspring by Early Pregnancy Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) Exposure Status.

The median gestational age at HbA1c testing was 9.0 weeks (interquartile range, 6.7-11.4 weeks); 83% of the testing was in the first trimester. Autism spectrum disorders include autistic disorders, Asperger syndrome, or pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified.

Discussion

In this study, there was no association between maternal HbA1c levels during early pregnancy and ASD in offspring when HbA1c levels were analyzed as a continuous variable or as a categorical measure if less than 6.5%. An association with HbA1c levels greater than 6.5% was found but was based on only 15 affected children. These findings are consistent with previous observations and the preconception counseling recommendation to optimize glycemic control with HbA1c levels greater than 6.5%.3

These results suggest that maternal glycemic control in early pregnancy may be important for ASD risk in offspring. Study limitations include the lack of information on maternal glycemic control throughout pregnancy, other prenatal and early life risk factors, paternal risk factors, and genetic factors as well as the relatively small sample size for pregnancies with HbA1c levels greater than 6.5%.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.Xiang AH, Wang X, Martinez MP, et al. Association of maternal diabetes with autism in offspring. JAMA. 2015;313(14):1425-1434. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.2707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiang AH, Wang X, Martinez MP, Page K, Buchanan TA, Feldman RK. Maternal type 1 diabetes and risk of autism in offspring. JAMA. 2018;320(1):89-91. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.7614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Diabetes Association . 13. Management of diabetes in pregnancy: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(suppl 1):S137-S143. doi: 10.2337/dc18-S013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]