Key Points

Question

Is artificial light at night while sleeping associated with weight gain and obesity?

Findings

In this cohort study of 43 722 women, artificial light at night while sleeping was significantly associated with increased risk of weight gain and obesity, especially in women who had a light or a television on in the room while sleeping. Associations do not appear to be explained by sleep duration and quality or other factors influenced by poor sleep.

Meaning

Exposure to artificial light at night while sleeping appears to be associated with increased weight, which suggests that artificial light exposure at night should be addressed in obesity prevention discussions.

This cohort study assesses whether exposure to artificial light at night while sleeping is associated with the prevalence and risk of general and central obesity among women.

Abstract

Importance

Short sleep has been associated with obesity, but to date the association between exposure to artificial light at night (ALAN) while sleeping and obesity is unknown.

Objective

To determine whether ALAN exposure while sleeping is associated with the prevalence and risk of obesity.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This baseline and prospective analysis included women aged 35 to 74 years enrolled in the Sister Study in all 50 US states and Puerto Rico from July 2003 through March 2009. Follow-up was completed on August 14, 2015. A total of 43 722 women with no history of cancer or cardiovascular disease who were not shift workers, daytime sleepers, or pregnant at baseline were included in the analysis. Data were analyzed from September 1, 2017, through December 31, 2018.

Exposures

Artificial light at night while sleeping reported at enrollment, categorized as no light, small nightlight in the room, light outside the room, and light or television in the room.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Prevalent obesity at baseline was based on measured general obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥30.0) and central obesity (waist circumference [WC] ≥88 cm, waist-to-hip ratio [WHR] ≥0.85, or waist-to-height ratio [WHtR]≥0.5). To evaluate incident overweight and obesity, self-reported BMI at enrollment was compared with self-reported BMI at follow-up (mean [SD] follow-up, 5.7 [1.0] years). Generalized log-linear models with robust error variance were used to estimate multivariable-adjusted prevalence ratios (PRs) and relative risks (RRs) with 95% CIs for prevalent and incident obesity.

Results

Among the population of 43 722 women (mean [SD] age, 55.4 [8.9] years), having any ALAN exposure while sleeping was positively associated with a higher prevalence of obesity at baseline, as measured using BMI (PR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.02-1.03), WC (PR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.09-1.16), WHR (PR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.00-1.08), and WHtR (PR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.04-1.09), after adjusting for confounding factors, with P < .001 for trend for each measure. Having any ALAN exposure while sleeping was also associated with incident obesity (RR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.06-1.34). Compared with no ALAN, sleeping with a television or a light on in the room was associated with gaining 5 kg or more (RR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.08-1.27; P < .001 for trend), a BMI increase of 10% or more (RR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.02-1.26; P = .04 for trend), incident overweight (RR, 1.22; 95% CI,1.06-1.40; P = .03 for trend), and incident obesity (RR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.13-1.57; P < .001 for trend). Results were supported by sensitivity analyses and additional multivariable analyses including potential mediators such as sleep duration and quality, diet, and physical activity.

Conclusions and Relevance

These results suggest that exposure to ALAN while sleeping may be a risk factor for weight gain and development of overweight or obesity. Further prospective and interventional studies could help elucidate this association and clarify whether lowering exposure to ALAN while sleeping can promote obesity prevention.

Introduction

A high-calorie diet and sedentary behaviors are the most commonly cited explanations for the obesity epidemic and are the main targets for obesity prevention.1 However, exposure to artificial light at night (ALAN) may contribute to the obesity pandemic.2,3 Increasing trends in light pollution during the past few decades parallel the rapid increase of obesity in the United States.4 Evidence from animal studies supports the hypothesis that light exposure at night may have direct effects on melatonin signaling, sleep disruption, and circadian rhythms, which could result in weight gain and obesity.4,5 ALAN has been shown to suppress expression of circadian clock genes and, in turn, alter feeding behaviors and lead to weight gain in rodents.6,7,8

There has been little investigation of the association between ALAN and obesity in humans. Evidence has been mostly limited to studies of shift workers, for whom occupational light exposures are much higher than those experienced by the general population.4,9 Although positive associations between ALAN while sleeping and weight gain or obesity were found in a few studies of the general population, the existing data are inconclusive because of limitations such as cross-sectional designs2,3,10,11,12 in which reverse causality cannot be ruled out, small samples,11,12 and lack of data on important confounders or potential mediators such as sleep characteristics, diet, and physical activity.2,3,10,11,12,13,14 Therefore, we examined the association between ALAN while sleeping and risk of obesity and weight gain during more than 5 years of follow-up using data from the Sister Study, a large prospective cohort study of US women.

Methods

Study Population

This investigation was based in the Sister Study, a nationwide prospective cohort study investigating environmental and genetic risk factors for breast cancer.15 A total of 50 884 US and Puerto Rican women were recruited from July 2003 through March 2009. Eligible women were aged 35 to 74 years without breast cancer and had at least 1 sister diagnosed with breast cancer. Study participants complete detailed follow-up questionnaires every 2 to 3 years to provide information on risk factors and changes in health status. Response rates have been greater than 90% throughout follow-up.15 The Sister Study was approved by the institutional review boards of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, and the Copernicus Group, Chicago, Illinois. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The present analysis uses Sister Study data release 5.0.2 with follow-up through August 14, 2015.

Assessment of ALAN While Sleeping and Sleep Characteristics

At baseline, women were asked about types of ALAN that were usually present while sleeping. Possible responses included “light from a small nightlight or clock radio,” “light from other rooms,” “light from outside shining in through windows at night, such as car headlights, street lights, or porch lights,” “light from a television on in the room for most or all of the night,” “1 or more lights on in the room,” and “daylight.” Respondents who responded “daylight” were excluded if they slept during daytime or lived in Alaska. Responses were recoded for analysis into 4 categories (no light, small nightlight in the room, light outside the room, and light or television on in the room). Women reporting more than 1 ALAN type were categorized at their highest level of ALAN exposure. Women who slept with a mask on or reported no light at all while sleeping were classified as experiencing no ALAN exposure.

Assessment of Obesity at Baseline and Follow-up

During the baseline home visit, height, weight, and hip and waist circumference (WC) were measured by trained study personnel. Height and weight were measured without shoes but with light clothing. Over skin or light clothing, WC was measured at the midpoint between the lowest rib on the right side and the top of the iliac crest, and hip circumference was measured horizontally level around the hips at the maximal protrusion of the buttocks. We used body mass index (BMI) (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) to determine prevalent obesity; overweight was defined as a BMI of at least 25.0 and obesity as a BMI of at least 30.0. Having a WC of at least 88 cm, waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) of at least 0.85, and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) of at least 0.5 was used to characterize central obesity. We identified incident overweight (BMI≥25.0) and obesity (BMI≥30.0) using self-reported weight and height at baseline and follow-up (mean [SD], 5.7 [1.0] years). Incidence of overweight was defined as the transition from a BMI of less than 25.0 at baseline to a BMI of 25.0 or more at follow-up; incidence of obesity as a transition from a BMI of less than 30.0 at baseline to a BMI of 30.0 or more at follow-up. In addition, we calculated the change in self-reported weight (in kilograms) and BMI from baseline to follow-up, with a weight gain of 5 kg or more16 and a BMI increase of 10% or more evaluated in relation to baseline ALAN values. Self-reported weights at baseline were highly correlated with measured weights (r = 0.99; mean [SD] difference for measured minus self-reported weight, 0.86 [0.01] kg).

Statistical Analysis

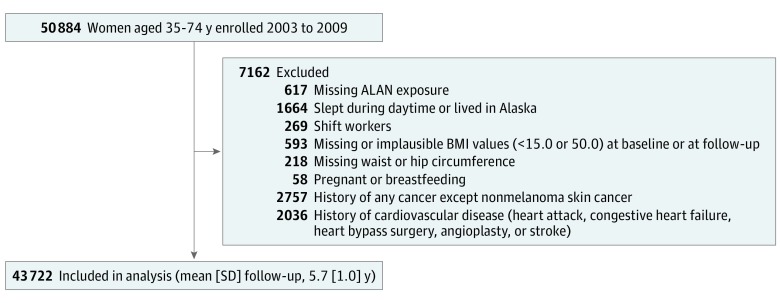

Data were analyzed from September 1, 2017, through December 31, 2018. After excluding participants for criteria detailed above, 43 722 women were included in the final analysis (Figure). We estimated prevalence ratios (PRs) and relative risks (RRs) for cross-sectional and prospective outcomes, respectively, with corresponding 95% CIs using generalized log-linear models with robust error variance.17,18 Tests for linear trend across categories of ALAN while sleeping were performed by modeling an ordinal variable for each ALAN category. Potential confounders, mediators, or effect modifiers were identified a priori based on literature review and presumed causal relationships among the covariates.19 The following covariates as ascertained at baseline were included in multivariable-adjusted models: age at enrollment, race/ethnicity, residential location, educational attainment, household income, household composition, marital status, smoking status, alcohol consumption, caffeine consumption, menopausal status at baseline, depression, and perceived stress.20 We also adjusted for the logarithm of follow-up time in prospective analyses.

Figure. Participant Flow Diagram.

After excluding participants meeting exclusion criteria, 43 722 women were included in the final analysis. Some women met more than 1 exclusion criterion. ALAN indicates artificial light at night; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

Exposure to ALAN may affect sleep quality, which in turn could affect diet and physical activity.6,9,13,21,22,23 Because these factors may be mediators of an association between ALAN and obesity, we did not adjust for them in our main analyses. Because we cannot identify a temporal relationship between ALAN while sleeping and potential mediators in this cross-sectional setting, we did not conduct formal mediation analysis. We did, however, conduct secondary analyses in which these factors were included as covariates because they could instead be confounders of cross-sectional associations with ALAN at baseline. We also performed secondary analyses adding sleep duration, waking, and bedtime patterns for the past 6 weeks; the length of time it took to fall asleep; frequency of waking at night (and turning on a light); frequency of napping; and use of sleep medication to the models. We also further considered total and leisure-time physical activity, consumption of fat and fiber, glycemic load, total energy intake, and nighttime snacking.

We assessed potential effect modification through stratified analysis and interaction testing using a likelihood ratio test. Furthermore, we conducted several sensitivity analyses: (1) exploring the association using percentage increase in BMI as a continuous variable, especially comparing the results from a subsample of women who had their height and weight remeasured at 7.9 years of median follow-up; (2) exploring the association separately for television on in the room and light on in the room as well as conducting a cluster analysis on women who had a television on while sleeping; (3) reanalysis (n = 16 537) with exclusion of participants who responded yes to waking up for any reason every night or most nights; (4) excluding women who reported taking naps; (5) reanalysis with exclusion of participants who developed incident cancers except nonmelanoma skin cancer during follow-up (n = 4807); (6) reanalysis using inverse probability weighting to address self-selective attrition and nonresponse24; and (7) reanalysis (n = 39 188) after randomly selecting 1 woman per sibship. Statistical significance was evaluated with 2-sided tests, with the level of significance at P < .05. SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

We included 43 722 women in the analysis (mean [SD] age, 55.4 [8.9] years). Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1, stratified by ALAN categories. Women with greater exposure to ALAN had higher mean BMI, WC, WHR, and WHtR and were more likely to be non-Hispanic black. They were less likely to have consistent waking and bedtime patterns and more likely to have less sleep, take a longer time to fall asleep, wake up at night, and take naps. They also used less sleep medication (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Table 1. General Characteristics at Baseline by ALAN Exposure While Sleepinga.

| Characteristic | ALAN Exposure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Light (n = 7807) | Small Nightlight in Room (n = 17 320) | Light Outside Room (n = 13 471) | Light/Television in Room (n = 5124) | |

| Age at baseline, mean (SD), y | 55.9 (8.8) | 55.4 (8.8) | 55.5 (9.1) | 54.0 (8.6) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 27.0 (5.7) | 27.0 (5.6) | 27.7 (5.8) | 29.2 (6.3) |

| Waist circumference, mean (SD), cm | 84.5 (13.8) | 84.6 (13.8) | 86.3 (14.3) | 89.6 (15.0) |

| Waist-to-hip ratio, mean (SD) | 0.80 (0.07) | 0.80 (0.08) | 0.81 (0.08) | 0.82 (0.08) |

| Waist-to-height ratio, mean (SD) | 0.52 (0.08) | 0.52 (0.08) | 0.53 (0.09) | 0.55 (0.09) |

| Sleep duration, mean (SD), h | 7.1 (1.1) | 7.2 (1.0) | 7.1 (1.0) | 6.7 (1.3) |

| Total MET-h/wk of physical activity, mean (SD) | 53.3 (32.8) | 51.1 (30.9) | 50.1 (30.4) | 48.6 (31.1) |

| Caffeine consumption, mean (SD), mg/db | 27.0 (37.8) | 27.3 (37.5) | 28.9 (39.3) | 29.9 (39.4) |

| Fiber consumption, mean (SD), g/db | 17.5 (8.8) | 17.3 (8.4) | 17.3 (8.3) | 15.9 (8.4) |

| Fat consumption, mean (SD), g/db | 66.9 (29.8) | 67.7 (29.5) | 69.5 (30.4) | 69.5 (33.9) |

| Total energy intake, mean (SD), kcal/db | 1606 (596) | 1621 (588) | 1653 (603) | 1646 (677) |

| Glycemic load, mean (SD)b | 82.4 (36.9) | 83.5 (36.1) | 86.4 (37.4) | 89.0 (43.4) |

| Health Eating Index–2015, mean (SD)b | 72.5 (9.4) | 72.3 (9.3) | 71.7 (9.3) | 69.0 (9.8) |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 6518 (83.5) | 15 385 (88.8) | 11 609 (86.2) | 3261 (63.6) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 653 (8.4) | 898 (5.2) | 819 (6.1) | 1350 (26.3) |

| Hispanicc | 441 (5.7) | 640 (3.7) | 679 (5.0) | 382 (7.5) |

| Other | 195 (2.5) | 394 (2.3) | 363 (2.7) | 131 (2.6) |

| Residential location, No. (%) | ||||

| Urban | 1658 (21.3) | 3985 (23.0) | 2495 (18.5) | 934 (18.3) |

| Suburban or small town | 4559 (58.5) | 10 591 (61.2) | 8093 (60.2) | 2957 (57.9) |

| Rural | 1575 (20.2) | 2720 (15.7) | 2864 (21.3) | 1217 (23.8) |

| Marital status, No. (%) | ||||

| Never married | 439 (5.6) | 680 (3.9) | 780 (5.8) | 397 (7.7) |

| Married or living as married | 5794 (74.2) | 13 803 (79.7) | 9993 (74.2) | 3487 (68.1) |

| Separated, divorced, or widowed | 1573 (20.2) | 2837 (16.4) | 2694 (20.0) | 1239 (24.2) |

| Educational attainment, No. (%) | ||||

| High school degree or less | 1037 (13.3) | 2456 (14.2) | 2073 (15.4) | 924 (18.0) |

| Some college | 2513 (32.2) | 5638 (32.6) | 4302 (31.9) | 2052 (40.1) |

| College degree or higher | 4256 (54.5) | 9225 (53.3) | 7095 (52.7) | 2147 (41.9) |

| Income, No. (%) | ||||

| <$49 999 | 1779 (22.8) | 3519 (20.3) | 3465 (25.7) | 1484 (29.0) |

| $50 000-$99 999 | 2975 (38.1) | 6854 (39.6) | 5405 (40.1) | 2056 (40.1) |

| ≥$100 000 | 2740 (35.1) | 6281 (36.3) | 4097 (30.4) | 1389 (27.1) |

| Missing | 313 (4.0) | 666 (3.8) | 504 (3.7) | 195 (3.8) |

| Family members aged <18 y, No. (%) | ||||

| None | 4381 (56.1) | 10 063 (58.1) | 7310 (54.3) | 2542 (49.6) |

| 1 | 993 (12.7) | 2120 (12.2) | 1640 (12.2) | 770 (15.0) |

| 2 | 725 (9.3) | 1793 (10.4) | 1433 (10.6) | 534 (10.4) |

| ≥3 | 284 (3.6) | 803 (4.6) | 635 (4.7) | 230 (4.5) |

| Missing | 1424 (18.2) | 2541 (14.7) | 2453 (18.2) | 1048 (20.5) |

| Family members aged ≥65 y, No. (%) | ||||

| None | 4781 (61.2) | 11 293 (65.2) | 8367 (62.1) | 3283 (64.1) |

| 1 | 779 (10.0) | 1660 (9.6) | 1260 (9.4) | 440 (8.6) |

| ≥2 | 823 (10.5) | 1826 (10.5) | 1391 (10.3) | 353 (6.9) |

| Missing | 1424 (18.2) | 2541 (14.7) | 2453 (18.2) | 1048 (20.5) |

| Alcohol consumption, No. (%) | ||||

| Never | 318 (4.1) | 610 (3.5) | 541 (4.0) | 178 (3.5) |

| Former | 1141 (14.6) | 2222 (12.8) | 2044 (15.2) | 934 (18.3) |

| Current alcohol consumption, drink/d, No. (%) | ||||

| ≤1 | 5394 (69.2) | 12 466 (72.1) | 9418 (69.9) | 3519 (68.8) |

| >1 | 939 (12.1) | 1999 (11.6) | 1454 (10.8) | 485 (9.5) |

| Smoking status, No. (%) | ||||

| Never | 4343 (55.6) | 10 099 (58.3) | 7966 (59.1) | 2567 (50.1) |

| Former | 2861 (36.7) | 6127 (35.4) | 4555 (33.8) | 1795 (35.0) |

| Current | 602 (7.7) | 1093 (6.3) | 948 (7.0) | 762 (14.9) |

| Leisure-time physical activity, MET-h/wk, No. (%) | ||||

| <7.5 | 3092 (39.6) | 7343 (42.4) | 6289 (46.7) | 2860 (55.9) |

| 7.5-21.0 | 2563 (32.9) | 5774 (33.4) | 4265 (31.7) | 1385 (27.1) |

| >21.0 | 2145 (27.5) | 4194 (24.2) | 2910 (21.6) | 875 (17.1) |

| Nighttime snacking, No. (%) | 562 (7.4) | 998 (5.9) | 913 (6.9) | 847 (17.5) |

| Menopause, No. (%) | 5166 (66.2) | 11 152 (64.4) | 8710 (64.7) | 3075 (60.1) |

| Perceived stress in highest quartile, No. (%) | 1621 (20.8) | 3499 (20.2) | 3229 (24.0) | 1626 (31.7) |

| Depression, No. (%) | 1514 (19.4) | 3296 (19.0) | 2919 (21.7) | 1168 (22.8) |

| Type 2 diabetes, No. (%) | 396 (5.1) | 797 (4.6) | 778 (5.8) | 413 (8.1) |

| Hypertension, No. (%) | 2359 (30.2) | 5166 (29.8) | 4433 (32.9) | 1992 (38.9) |

| High cholesterol level, No. (%) | 2557 (32.8) | 5908 (34.1) | 4820 (35.8) | 1843 (36.0) |

Abbreviations: ALAN, artificial light at night; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); MET, metabolic equivalent.

Data are from the Sister Study, 2003 to 2009. Owing to missing data, numbers may not total column heads. Percentages have been rounded and may not total 100.

Calculated after excluding women who reported implausibly extreme energy intakes (<500 and >5000 kcal/d).

Puerto Ricans were categorized as Hispanic, regardless of their race.

Exposure to ALAN while sleeping was significantly positively associated with each obesity measure at baseline (Table 2). Exposure to any light while sleeping was positively associated with general overweight and obesity and central obesity. Compared with no light while sleeping, sleeping with a television or a light on in the room was associated with a BMI of at least 30.0 (PR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.05-1.08), BMI of at least 25.0 (PR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.04-1.06), WC of at least 88 cm (PR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.18-1.28), WHR of at least 0.85 (PR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.07-1.20), and WHtR of at least 0.5 (PR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.11-1.18) after adjusting for confounding factors. Increasing trends of obesity prevalence were found with increasing levels of ALAN (P < .001 for trend) (Table 2). Associations remained but were attenuated when potential mediators, including sleep duration and quality, diet, and physical activity, were included (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Association Between Exposure to ALAN While Sleeping and Measures of Prevalent Obesity.

| Obesity Variable | ALAN Exposure | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No ALAN Exposure (n = 7807) | Small Nightlight in Room (n = 17 320) | Light Outside Room (n = 13 471) | Light/Television in Room (n = 5124) | P Value for Trend | Any ALAN Exposure (n = 35 915) | |

| BMI≥30.0 | ||||||

| Cases, % | 25.4 | 25.8 | 30.0 | 40.0 | NA | 29.4 |

| Age-adjusted PR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 1.04 (1.03-1.05) | 1.12 (1.10-1.13) | <.001 | 1.03 (1.02-1.04) |

| Multivariable-adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 1 [Reference] | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | 1.03 (1.02-1.04) | 1.06 (1.05-1.08) | <.001 | 1.03 (1.02-1.03) |

| BMI≥25.0 | ||||||

| Cases, % | 56.7 | 58.0 | 62.4 | 71.6 | NA | 61.6 |

| Age-adjusted PR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | 1.04 (1.03-1.05) | 1.10 (1.09-1.11) | <.001 | 1.03 (1.02-1.04) |

| Multivariable-adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 1 [Reference] | 1.01 (1.01-1.02) | 1.03 (1.03-1.04) | 1.05 (1.04-1.06) | <.001 | 1.03 (1.02-1.04) |

| Waist Circumference ≥88 cm | ||||||

| Cases, % | 35.5 | 36.3 | 41.6 | 50.5 | NA | 40.3 |

| Age-adjusted PR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | 1.18 (1.14-1.22) | 1.45 (1.40-1.51) | <.001 | 1.15 (1.11-1.18) |

| Multivariable-adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 1 [Reference] | 1.05 (1.02-1.09) | 1.16 (1.12-1.20) | 1.22 (1.18-1.28) | <.001 | 1.12 (1.09-1.16) |

| Waist-to-Hip Ratio ≥0.85 | ||||||

| Cases, % | 25.7 | 24.4 | 27.2 | 33.9 | NA | 26.8 |

| Age-adjusted PR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 0.96 (0.92-1.00) | 1.06 (1.02-1.12) | 1.37 (1.29-1.44) | <.001 | 1.05 (1.01-1.10) |

| Multivariable-adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 1 [Reference] | 0.99 (0.95-1.04) | 1.06 (1.01-1.11) | 1.13 (1.07-1.20) | <.001 | 1.04 (1.00-1.08) |

| Waist-to-Height Ratio ≥0.5 | ||||||

| Cases, % | 52.1 | 52.1 | 57.0 | 66.5 | NA | 56.0 |

| Age-adjusted PR(95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 1.01 (0.98-1.03) | 1.10 (1.07-1.13) | 1.31 (1.27-1.35) | <.001 | 1.09 (1.06-1.11) |

| Multivariable-adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 1 [Reference] | 1.02 (1.00-1.05) | 1.09 (1.06-1.11) | 1.15 (1.11-1.18) | <.001 | 1.07 (1.04-1.09) |

Abbreviations: ALAN, artificial light at night; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); NA, not applicable; PR, prevalence ratio.

Adjusted for age at baseline; race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or other); residential location (urban, suburban or small town, or rural); educational attainment (high school degree or less, some college, or college degree or higher); household income (<$49 999, $50 000-$99 999,≥$100 000, or missing); number of family members younger than 18 years living in household (none, 1, 2, ≥3, or missing); number of family members 65 years or older living in household (none, 1, ≥2, or missing); marital status (never married, married, or other); smoking status (never, current, or past); alcohol consumption (never, former, current ≤1 drink per day, or current >1 drink per day); caffeine consumption (quintiles); menopausal status; depression; and perceived stress (quartile).

Participants not included in prospective analyses because they did not provide updated BMI (4772 [10.9%]) were more likely to have a light or a television on in the room while sleeping (983 [20.6%] vs 4141 [10.6%]) and had higher mean (SD) BMI (28.8 [6.4] vs 27.3 [5.7]), WC (89.1 [14.9] vs 85.2 [14.0] cm), WHR (0.82 [0.08] vs 0.80 [0.08]), and WHtR (0.54 [0.09] vs 0.52 [0.09]) at baseline compared with those included in the prospective analyses (eTable 3 in the Supplement). However, results were not materially changed in an analysis of prevalent obesity in which these women were excluded. We also found evidence that sleep duration and other sleep characteristics, including insufficient sleep (PR for <7 hours, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.10-1.03), turning on the light when awakened at night (PR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.01-1.03), inconsistent wake-up time (PR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02-1.05) and bedtime (PR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.04-1.06), longer time to fall asleep (PR for >1 hour, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02-1.06), more frequent napping (PR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.01-1.03), and use of sleep medications (PR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.98-1.00) were individually associated with some obesity variables (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

In the prospective analysis, associations between ALAN exposure while sleeping and weight gain of 5 kg or more, BMI increase of 10% or more, incident overweight, and obesity during follow-up are shown in Table 3 and the eFigure in the Supplement. Among women with BMI of less than 30.0 at baseline, any light on while sleeping was associated with incident obesity (adjusted RR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.06-1.34). Compared with no light on while sleeping, sleeping with a television or a light on in the room was associated with gaining 5 kg or more (RR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.08-1.27; P < .001 for trend), 10% or greater BMI increase (RR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.02-1.26; P = .04 for trend), incident overweight (RR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.06-1.40; P = .03 for trend), and incident obesity (RR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.13-1.57; P < .001 for trend). Associations remained after further adjusting for sleep duration and quality, diet, and physical activity (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Insufficient duration of sleep (<7 hours), turning on a light when awakened at night, inconsistent bedtime, longer time to fall asleep, more frequent napping, and use of sleep medication were themselves associated with a weight gain of 5 kg or more, incident overweight, or obesity (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Table 3. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping, Subsequent Weight Gain, and Incident Obesity.

| Outcome | ALAN Exposure | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No ALAN Exposure | Small Nightlight in Room | Light Outside Room | Light/Television in Room | P Value for Trend | Any ALAN Exposure | |

| Weight Gain of ≥5 kg | ||||||

| No. of events | 1080 | 2509 | 2040 | 893 | NA | 5442 |

| Cumulative incidence | 15.6 | 15.9 | 16.7 | 21.5 | NA | 16.9 |

| Age-adjusted RR (95% CI)a | 1 [Reference] | 1.00 (0.94-1.07) | 1.05 (0.98-1.13) | 1.29 (1.19-1.40) | <.001 | 1.06 (1.00-1.12) |

| Multivariable-adjusted RR (95% CI)b | 1 [Reference] | 1.01 (0.94-1.07) | 1.03 (0.96-1.10) | 1.17 (1.08-1.27) | <.001 | 1.04 (0.98-1.10) |

| BMI Increase of ≥10% | ||||||

| No. of events | 754 | 1796 | 1439 | 591 | NA | 3826 |

| Cumulative incidence | 10.9 | 11.4 | 11.9 | 14.3 | NA | 11.9 |

| Age-adjusted RR (95% CI)a | 1 [Reference] | 1.02 (0.94-1.10) | 1.06 (0.97-1.15) | 1.23 (1.11-1.36) | <.001 | 1.06 (0.99-1.14) |

| Multivariable-adjusted RR (95% CI)b | 1 [Reference] | 1.04 (0.96-1.12) | 1.04 (0.96-1.13) | 1.13 (1.02-1.26) | .04 | 1.05 (0.98-1.13) |

| Overweight (BMI≥25.0)c | ||||||

| No. of events | 459 | 1110 | 766 | 266 | NA | 2142 |

| Cumulative incidence | 14.8 | 16.5 | 16.4 | 21.5 | NA | 16.9 |

| Age-adjusted RR (95% CI)a | 1 [Reference] | 1.10 (1.00-1.22) | 1.09 (0.98-1.22) | 1.40 (1.23-1.61) | <.001 | 1.13 (1.03-1.24) |

| Multivariable-adjusted RR (95% CI)b | 1 [Reference] | 1.11 (1.00-1.22) | 1.08 (0.97-1.20) | 1.22 (1.06-1.40) | .03 | 1.11 (1.01-1.22) |

| Obesity (BMI≥30.0)d | ||||||

| No. of events | 306 | 791 | 628 | 246 | NA | 1665 |

| Cumulative incidence | 5.8 | 6.7 | 7.3 | 9.6 | NA | 7.3 |

| Age-adjusted RR (95% CI)a | 1 [Reference] | 1.14 (1.00-1.29) | 1.24 (1.08-1.41) | 1.59 (1.35-1.86) | <.001 | 1.23 (1.09-1.38) |

| Multivariable-adjusted RR (95% CI)b | 1 [Reference] | 1.15 (1.01-1.30) | 1.20 (1.05-1.37) | 1.33 (1.13-1.57) | <.001 | 1.19 (1.06-1.34) |

Abbreviations: ALAN, artificial light at night; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared; NA, not applicable; RR, relative risk.

Adjusted for logarithm of follow-up time.

Adjusted for age at baseline; logarithm of follow-up time; race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or other); residential location (urban, suburban or small town, or rural); educational attainment (high school degree or less, some college, or college degree or higher); household income (<$49 999, $50 000-$99 999,≥$100 000, or missing); number of family members younger than 18 years living in household (none, 1, 2, ≥3, or missing); number of family members 65 years or older living in household (none, 1, ≥2, or missing); marital status (never married, married, or other); smoking status (never, current, or past); alcohol consumption (never, former, current ≤1 drink per day, or current >1 drink per day); caffeine consumption (quintiles); menopausal status; depression; and perceived stress (quartile).

Among women with a BMI of less than 25.0 at baseline (n = 17 179).

Among women with a BMI of less than 30.0 at baseline (n = 31 188).

In analyses stratified by potential modifiers of the association of ALAN and gaining 5 kg or more (Table 4), the association was stronger among women with normal weight (adjusted RR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.00-1.38) or overweight (adjusted RR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.01-1.32) than among women with obesity at baseline (adjusted RR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.93-1.21; P = .01 for interaction). Interestingly, among women who consumed diets with a higher score on the Healthy Eating Index (HEI)–2015 (ie, higher-quality diet) and women who reported more leisure-time physical activity, the association between ALAN and weight gain was stronger (adjusted RR for higher HEI-2015, 1.30 [95% CI, 1.09-1.55; P = .03 for interaction]; adjusted RR for more activity, 1.35 [95% CI, 1.12-1.63; P = .05 for interaction]), similar to results with incident obesity as an outcome (eTable 6 in the Supplement). However, among those with no light on in the room, low HEI-2015 was associated with weight gain (adjusted RR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.27-1.70) and obesity (adjusted RR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.52-2.76), as was insufficient leisure-time physical activity (adjusted RR for overweight, 1.35 [95% CI, 1.16-1.56]; adjusted RR for obesity, 2.21 [95% CI, 1.63-2.98]), despite the absence of such associations among those with ALAN exposure (eTable 7 in the Supplement). We found no differential association by level of residential urbanization, which might affect exposure to light from outside the room.

Table 4. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping and Risk of Weight Gain of 5 kg or More Stratified by Selected Factors.

| Stratification Factor | No. of Participants at Baseline | Association of Weight Gain of ≥5 kg With ALAN Exposure, Adjusted RR (95% CI)a | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| For Trendb | For Interaction | |||

| BMI | ||||

| 18.5 to <25.0 (normal weight) | 16 695 | 1.17 (1.00-1.38) | .10 | .01 |

| 25.0 to <30.0 (overweight) | 14 009 | 1.15 (1.01-1.32) | .22 | |

| ≥30.0 (obesity) | 12 534 | 1.06 (0.93-1.21) | .24 | |

| Age group, y | ||||

| <50 | 12 678 | 1.08 (0.96-1.22) | .15 | .09 |

| 50-59 | 17 290 | 1.21 (1.06-1.38) | .007 | |

| ≥60 | 13 754 | 1.31 (1.08-1.59) | .04 | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 36 773 | 1.19 (1.08-1.30) | <.001 | .92 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 3720 | 1.07 (0.86-1.34) | .71 | |

| Hispanic | 2142 | 1.41 (0.97-2.05) | .33 | |

| Other | 1083 | 1.49 (0.86-2.60) | .37 | |

| Residential location | ||||

| Urban | 9072 | 1.21 (1.00-1.46) | .03 | .70 |

| Suburban, small town | 26 200 | 1.15 (1.03-1.27) | .05 | |

| Rural | 8376 | 1.25 (1.04-1.49) | .006 | |

| Educational attainment | ||||

| High school degree or less | 6490 | 0.96 (0.78-1.18) | .89 | .13 |

| Some college | 14 505 | 1.28 (1.13-1.46) | <.001 | |

| College degree or higher | 22 723 | 1.18 (1.04-1.33) | .02 | |

| Income | ||||

| <$49 999 | 10 247 | 1.13 (0.97-1.33) | .35 | .12 |

| $50 000-$99 999 | 17 290 | 1.17 (1.03-1.32) | .004 | |

| ≥$100 000 | 14 507 | 1.21 (1.04-1.41) | .05 | |

| Household composition | ||||

| Absence of a family member aged <18 y or ≥65 y | 16 306 | 1.20 (1.05-1.38) | .005 | .11 |

| Presence of a family member aged <18 y or ≥65 y | 19 950 | 1.14 (1.01-1.28) | .07 | |

| Smoking | ||||

| Never | 24 975 | 1.20 (1.08-1.35) | .002 | .53 |

| Former | 15 338 | 1.14 (0.98-1.31) | .15 | |

| Current | 3405 | 1.24 (1.00-1.54) | .04 | |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| Never/former | 7988 | 1.20 (1.00-1.44) | .10 | .53 |

| Current, ≤1 drink per day | 30 797 | 1.15 (1.05-1.27) | .005 | |

| Current, >1 drink per day | 4877 | 1.28 (0.98-1.68) | .10 | |

| Sleep duration, hc | ||||

| <7 | 12 371 | 1.19 (1.04-1.37) | .05 | .43 |

| 7-9 | 30 918 | 1.16 (1.04-1.28) | .005 | |

| Leisure-time physical activity, MET-h/wk | ||||

| <7.5 (insufficient) | 19 584 | 1.10 (0.98-1.23) | .06 | .05 |

| 7.5-21.0 (moderate) | 13 987 | 1.18 (1.01-1.37) | .09 | |

| ≥21 (high) | 10 124 | 1.35 (1.12-1.63) | .03 | |

| Healthy Eating Index–2015 tertiled | ||||

| 1 (lower diet quality) | 14 137 | 1.05 (0.93-1.19) | .26 | .03 |

| 2 | 14 137 | 1.20 (1.04-1.39) | .06 | |

| 3 (higher diet quality) | 14 137 | 1.30 (1.09-1.55) | .01 | |

| Nighttime snacking | ||||

| No | 39 173 | 1.21 (1.11-1.32) | <.001 | .08 |

| Yes | 3320 | 0.95 (0.76-1.19) | .93 | |

| Type 2 diabetes, hypertension, or high cholesterol level | ||||

| No | 21 340 | 1.18 (1.05-1.32) | .005 | .13 |

| Yes | 22 289 | 1.14 (1.02-1.28) | .06 | |

Abbreviations: ALAN, artificial light at night; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); MET, metabolic equivalent; RR, relative risk.

ALAN exposure was measured as light or television on in room vs no light. Adjusted for age at baseline; logarithm of follow-up time; race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or other); residential location (urban, suburban or small town, or rural); educational attainment (high school degree or less, some college, or college degree or higher); household income (<$49 999, $50 000-$99 999,≥$100 000, or missing); number of family members younger than 18 years living in household (none, 1, 2, ≥3, or missing); number of family members 65 years or older living in household (none, 1, ≥2, or missing); marital status (never married, married, or other); smoking status (never, current, or former); alcohol consumption (never, former, current ≤1 drink per day, or current >1 drink per day); caffeine consumption (quintiles); menopausal status; depression; and perceived stress (quartile), except a stratifying variable.

Indicates tests for linear trend across each category of ALAN exposure while sleeping, with exposure categories defined as no light, small nightlight, light outside the room, and light or television in room.

Participants with a sleep duration of longer than 9 hours were not included in the analysis owing to small sample size (n = 377).

Calculated after excluding women who reported implausibly extreme energy intakes (<500 and >5000 kcal/d).

In a sensitivity analysis for the association between ALAN and percentage increase in BMI as a continuous variable, estimates of increase were attenuated using self-reported BMI compared with measured BMI (eTable 8 in the Supplement). When we further investigated the association separately for television on in the room and light on in the room, associations with television and light were similar. In addition, compared with no light on while sleeping, we found no increased risk of weight gain (adjusted RR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.96-1.24), but an increased risk of incident overweight and obesity (adjusted RR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.17-1.97) in the cluster of women who were more likely to be nonwhite and had lower levels of physical activity and poorer diet quality, lower educational attainment and household income, higher stress and depression, and worse sleep characteristics (eTables 9 and 10 in the Supplement). When we excluded women who responded yes to waking up for any reason every night or most nights, the strength of association increased, especially when weight gain (adjusted RR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.12-1.45) or incident obesity (adjusted RR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.25-2.14) was the outcome (eTable 11 in the Supplement). Similar associations were observed after excluding women who reported taking naps (eTable 12 in the Supplement). The results were not materially altered when we used inverse probability weighting to address attrition and nonresponse (eTable 13 in the Supplement) or limited analysis to 1 woman per sibship (eTable 14 in the Supplement). Although women who developed cancer during follow-up could have had cancer-related weight loss, findings were not materially changed in analyses excluding these women.

Discussion

In this large prospective cohort of women followed up for more than 5 years, exposure to ALAN while sleeping was significantly associated with an increased risk of weight gain and the development of obesity. In particular, sleeping with a television or a light on in the room was positively associated with gaining 5 kg or more and the development of overweight and obesity, even after adjusting for measures of inadequate sleep, diet, and physical activity. This observation, although in line with findings from animal studies,4,5,7 appears to be the first epidemiologic evidence of an association between ALAN while sleeping and risk of weight gain and obesity.

Our results were consistent with those from previous cross-sectional studies. In a study of UK women,10 the odds of prevalent general and central obesity based on self-report increased with increasing self-reported levels of ALAN exposure. This result is consistent with our baseline results, which were based on objectively measured obesity variables. In a study of elderly Japanese individuals,11 objectively measured ALAN using a measure of luminescence (mean, ≥3 vs <3 lux) was associated with higher body weight, BMI, and WC. Satellite data have been used to compare the levels of outdoor ALAN by community or region. Although satellite images of nighttime illumination may not reflect individual exposures to levels of ALAN sufficient to affect circadian pathways,9 outdoor ALAN was associated with country-level overweight and obesity prevalence2 and with prevalent obesity.3 Consistent findings have occurred in the association between shift work and increased body weight, BMI, and risk of overweight.25 However, the studies in shift workers may not be applicable to the general population because shift workers experience behavioral circadian desynchronization, which cannot be separated from light effects, and their levels of exposure to ALAN would be substantially higher than those of the general population.4,9 Our findings extend the literature suggesting that ALAN exposure while sleeping may increase the risk of weight gain, overweight, and obesity in an ordinary population.

Our stratified analyses suggest that multiple factors, including age, diet, and physical activity, might be related to the association between ALAN while sleeping and a weight gain of 5 kg or more. Interestingly, the association was more pronounced among women who had a higher HEI-2015 and women who reported more leisure-time physical activity. In a study of sleep duration and incident obesity in US adults,26 short sleep duration was significantly associated with weight gain exclusively in women who spent less time sitting. A similar finding was observed in physically active men in the same study. Sleep characteristics might contribute less to weight gain among individuals with unhealthy lifestyle patterns because those with poor diet or low levels of physical activity are already at high risk of developing obesity. In contrast, among those with no light on in the room, low HEI-2015 and insufficient leisure-time physical activity were both associated with weight gain and obesity (eTable 7 in the Supplement).

It has been speculated that extended exposure to ALAN could disrupt sleep and decrease sleep duration,6,9,13 which in turn would increase weight gain and risk of obesity.21,27 ALAN was associated with shorter sleep duration in the Sister Study (eTable 15 in the Supplement). Two main pathways involved in this association include increased energy intake and decreased energy expenditure, both of which contribute to positive energy balance.28 Energy intake may be increased by behavioral and cognitive changes toward seeking high energy–dense foods,29 as well as changing levels of appetite-regulating hormones such as leptin, ghrelin, and glucagonlike peptide-1.22,30 A shorter sleep duration also provides more time in the wakefulness state, which simply allows for more time to consume food or increase one’s energy intake.21 Chronic partial sleep deprivation may decrease energy expenditure by lowering physical activity secondary to daytime fatigue.23,31 Recent meta-analyses of intervention studies evaluating the effects of sleep deprivation on energy balance32,33 support a greater contribution of energy intake than energy expenditure to positive energy balance.

However, the estimated effect of ALAN exposure on weight gain was not altered by inclusion of sleep characteristics, diet, or physical activity as covariates. The association between ALAN and those potential mediators might not be interpretable owing to cross-sectional assessment of these variables in which a temporal relationship cannot be determined. In addition, because there was little attenuation of the estimates in the multivariable models that adjusted for all potential mediators, other factors may play a stronger mediating role in this association. An alternative mechanism may involve a direct role of light; exposure to ALAN may directly suppress production of melatonin in the pineal gland, leading to disrupted circadian rhythmicity.9 Animal studies have demonstrated that body weight is decreased owing to reduced melatonin levels secondary to lower light levels.34,35 Exposure to ALAN may also act as a chronic stressor that disrupts diurnal variation in stress hormones such as glucocorticoids36,37 or may affect metabolism directly,7 in a way that would in turn contribute to weight gain.4

In addition to light from having a television on in the room, which was assessed in the present study, artificial light exposure from other screen-based electronic devices, including smartphones, computers, tablets, and e-readers, have been associated with sleep latency, poor sleep quantity and quality, and excessive daytime sleepiness.38,39,40 Short-wavelength–enriched light (eg, blue light) emitted from devices may lead to greater levels of melatonin suppression and circadian disruption compared with lights with longer wavelengths.40,41 Current evidence has been mostly limited to adolescents or younger populations,39 and the role of electronic media devices in relation to obesity should be considered in other age groups.

Our findings may have public health implications. The prevalence of obesity has increased substantially during the last few decades, especially in US women.42 The 2 most common strategies for obesity prevention are promoting healthy diets and increased exercise levels.1,43 However, adherence to healthy lifestyle habits is less than optimal44; there may be barriers to maintaining a healthy lifestyle,45 which may explain why obesity is not decreasing. Given the association found between exposure to ALAN while sleeping and subsequent weight gain and obesity in our study and the cross-sectional evidence from other studies, public health strategies to decrease obesity might consider interventions aimed at reducing ALAN while sleeping. However, ALAN exposure while sleeping might reflect a constellation of measures of socioeconomic disadvantage and unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, all of which could contribute to weight gain and obesity. We were unable to disentangle the temporal relationship between exposure to ALAN and other factors, including unhealthy diet, sedentary lifestyle, stress, and other sleep characteristics. Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that the association between ALAN and obesity is not causal, despite multivariable adjustment and various sensitivity analyses.

Strengths and Limitations

The major strengths of this study include a prospective design with a large sample size and high rates of follow-up. Comprehensive information on potential confounders and mediating factors in the association between ALAN while sleeping and risk of weight gain and obesity helps to strengthen our results. On the other hand, we were unable to account for change in exposure to ALAN over time. Exposure to ALAN was based on self-reported data, and we did not have objective information on the intensity (eg, light-emitting diode, fluorescent, or incandescent), wavelength (eg, blue), duration, or timing of light exposure. Different types of light appear to vary in terms of the time needed to reduce melatonin production.6 Furthermore, we did not ask women why they kept the light on while sleeping. Change in weight was also based on self-reported data, which is prone to misclassification, especially in higher BMI categories.46 Findings from our sensitivity analysis comparing self-reported BMI with measured BMI in relation to percentage increase in BMI suggest that our main results might have been underestimated. Self-reported information on the covariates including diet, physical activity, and sleep characteristics may also be prone to measurement error, but the effect of such errors on estimation could lead to bias toward the null.47,48 The relatively high socioeconomic status of participants might limit generalizability of study findings.

Conclusions

Our findings provide evidence that exposure to ALAN while sleeping may be a risk factor for weight gain, overweight, and obesity and suggest that lowering exposure to ALAN while sleeping might be a useful intervention for obesity prevention. However, ALAN exposure while sleeping represents a constellation of socioeconomic disadvantage measures and unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, all of which could contribute to weight gain and obesity. Further prospective or interventional studies are needed.

eTable 1. Other Baseline Sleep Characteristics by Exposure to ALAN While Sleeping

eTable 2. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping and Prevalent Obesity, Weight Gain and Incident Obesity, With Further Adjustment for Confounders That Could Also Be Mediators of Associations Between ALAN Exposure at Night and Obesity

eTable 3. Comparison of Baseline Characteristics Between Those With and Without Body Mass Index Estimates at Follow-up

eTable 4. Prevalence Ratios and 95% CIs for the Association Between Other Sleep Characteristics and Measures of Prevalent Obesity

eTable 5. Relative Risks and 95% CIs for Other Sleep Characteristics, Subsequent Weight Gain, and Incident Obesity

eTable 6. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping and Incident Obesity (BMI≥30.0) Stratified by Selected Factors

eTable 7. Adjusted Relative Risks and 95% CIs for the Joint Association of ALAN Exposure, Leisure Time Physical Activity, and Healthy Eating Index–2015 With Subsequent Weight Gain of ≥5 kg and Incident Obesity

eTable 8. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping and Subsequent Weight Gain Using Percent Increase in BMI as a Continuous Variable

eTable 9. Comparison of Baseline Characteristics Between 2 Categories (Clusters) of Women With Television in Room

eTable 10. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping, Subsequent Weight Gain, and Incident Obesity Including Adjustment for Categories (Clusters) of Women With Television in Room

eTable 11. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping, Subsequent Weight Gain and Incident Obesity, After Excluding Women Who Responded “Yes” to Waking Up for Any Reason Every Night or Most Nights (n = 26 849)

eTable 12. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping, Subsequent Weight Gain, and Incident Obesity, After Excluding Women Who Reported Taking Naps

eTable 13. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping, Subsequent Weight Gain, And Incident Obesity With Inverse Probability Weighting to Account for Loss to Follow-up

eTable 14. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping, Subsequent Weight Gain, And Incident Obesity in Analysis Limited to 1 Randomly Selected Woman per Sibship (n = 39 188)

eTable 15. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping and Sleep Hours

eFigure. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping, Subsequent Weight Gain, and Incident Obesity

References

- 1.Nestle M, Jacobson MF. Halting the obesity epidemic: a public health policy approach. Public Health Rep. 2000;115(1):12-24. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.1.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rybnikova NA, Haim A, Portnov BA. Does artificial light-at-night exposure contribute to the worldwide obesity pandemic? Int J Obes (Lond). 2016;40(5):815-823. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koo YS, Song JY, Joo EY, et al. Outdoor artificial light at night, obesity, and sleep health: cross-sectional analysis in the KoGES study. Chronobiol Int. 2016;33(3):301-314. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2016.1143480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fonken LK, Nelson RJ. The effects of light at night on circadian clocks and metabolism. Endocr Rev. 2014;35(4):648-670. doi: 10.1210/er.2013-1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fonken LK, Aubrecht TG, Meléndez-Fernández OH, Weil ZM, Nelson RJ. Dim light at night disrupts molecular circadian rhythms and increases body weight. J Biol Rhythms. 2013;28(4):262-271. doi: 10.1177/0748730413493862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Touitou Y, Reinberg A, Touitou D. Association between light at night, melatonin secretion, sleep deprivation, and the internal clock: health impacts and mechanisms of circadian disruption. Life Sci. 2017;173:94-106. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fonken LK, Workman JL, Walton JC, et al. Light at night increases body mass by shifting the time of food intake. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(43):18664-18669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008734107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopez-Minguez J, Gómez-Abellán P, Garaulet M. Circadian rhythms, food timing and obesity. Proc Nutr Soc. 2016;75(4):501-511. doi: 10.1017/S0029665116000628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lunn RM, Blask DE, Coogan AN, et al. Health consequences of electric lighting practices in the modern world: a report on the National Toxicology Program’s workshop on shift work at night, artificial light at night, and circadian disruption. Sci Total Environ. 2017;607-608:1073-1084. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.07.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McFadden E, Jones ME, Schoemaker MJ, Ashworth A, Swerdlow AJ. The relationship between obesity and exposure to light at night: cross-sectional analyses of over 100,000 women in the Breakthrough Generations Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(3):245-250. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Obayashi K, Saeki K, Iwamoto J, et al. Exposure to light at night, nocturnal urinary melatonin excretion, and obesity/dyslipidemia in the elderly: a cross-sectional analysis of the HEIJO-KYO study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(1):337-344. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reid KJ, Santostasi G, Baron KG, Wilson J, Kang J, Zee PC. Timing and intensity of light correlate with body weight in adults. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e92251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gangwisch JE. Invited commentary: nighttime light exposure as a risk factor for obesity through disruption of circadian and circannual rhythms. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(3):251-253. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haus E, Reinberg A, Mauvieux B, Le Floc’h N, Sackett-Lundeen L, Touitou Y. Risk of obesity in male shift workers: a chronophysiological approach. Chronobiol Int. 2016;33(8):1018-1036. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2016.1167079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandler DP, Hodgson ME, Deming-Halverson SL, et al. ; Sister Study Research Team . The Sister Study cohort: baseline methods and participant characteristics. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(12):127003. doi: 10.1289/EHP1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases: Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Heath Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702-706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins JM. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology. 1999;10(1):37-48. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199901000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385-396. doi: 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel SR. Reduced sleep as an obesity risk factor. Obes Rev. 2009;10(suppl 2):61-68. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00664.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taheri S, Lin L, Austin D, Young T, Mignot E. Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS Med. 2004;1(3):e62. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dinges DF, Pack F, Williams K, et al. Cumulative sleepiness, mood disturbance, and psychomotor vigilance performance decrements during a week of sleep restricted to 4-5 hours per night. Sleep. 1997;20(4):267-277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hernán MA, Brumback B, Robins JM. Marginal structural models to estimate the causal effect of zidovudine on the survival of HIV-positive men. Epidemiology. 2000;11(5):561-570. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Proper KI, van de Langenberg D, Rodenburg W, et al. The relationship between shift work and metabolic risk factors: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(5):e147-e157. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao Q, Arem H, Moore SC, Hollenbeck AR, Matthews CE. A large prospective investigation of sleep duration, weight change, and obesity in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(11):1600-1610. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park YJ, Lee WC, Yim HW, Park YM. The association between sleep and obesity in Korean adults [in Korean]. J Prev Med Public Health. 2007;40(6):454-460. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2007.40.6.454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.St-Onge MP. Sleep-obesity relation: underlying mechanisms and consequences for treatment. Obes Rev. 2017;18(suppl 1):34-39. doi: 10.1111/obr.12499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaput JP. Sleep patterns, diet quality and energy balance. Physiol Behav. 2014;134:86-91. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.St-Onge MP, O’Keeffe M, Roberts AL, RoyChoudhury A, Laferrère B. Short sleep duration, glucose dysregulation and hormonal regulation of appetite in men and women. Sleep. 2012;35(11):1503-1510. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmid SM, Hallschmid M, Jauch-Chara K, et al. Short-term sleep loss decreases physical activity under free-living conditions but does not increase food intake under time-deprived laboratory conditions in healthy men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(6):1476-1482. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al Khatib HK, Harding SV, Darzi J, Pot GK. The effects of partial sleep deprivation on energy balance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017;71(5):614-624. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2016.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Capers PL, Fobian AD, Kaiser KA, Borah R, Allison DB. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of the impact of sleep duration on adiposity and components of energy balance. Obes Rev. 2015;16(9):771-782. doi: 10.1111/obr.12296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walton JC, Weil ZM, Nelson RJ. Influence of photoperiod on hormones, behavior, and immune function. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2011;32(3):303-319. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2010.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bartness TJ, Demas GE, Song CK. Seasonal changes in adiposity: the roles of the photoperiod, melatonin and other hormones, and sympathetic nervous system. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2002;227(6):363-376. doi: 10.1177/153537020222700601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Griefahn B, Kuenemund C, Robens S. Shifts of the hormonal rhythms of melatonin and cortisol after a 4 h bright-light pulse in different diurnal types. Chronobiol Int. 2006;23(3):659-673. doi: 10.1080/07420520600650679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leproult R, Colecchia EF, L’Hermite-Balériaux M, Van Cauter E. Transition from dim to bright light in the morning induces an immediate elevation of cortisol levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(1):151-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Exelmans L, Van den Bulck J. Bedtime, shuteye time and electronic media: sleep displacement is a two-step process. J Sleep Res. 2017;26(3):364-370. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carter B, Rees P, Hale L, Bhattacharjee D, Paradkar MS. Association between portable screen-based media device access or use and sleep outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(12):1202-1208. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang AM, Aeschbach D, Duffy JF, Czeisler CA. Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(4):1232-1237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418490112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.West KE, Jablonski MR, Warfield B, et al. Blue light from light-emitting diodes elicits a dose-dependent suppression of melatonin in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2011;110(3):619-626. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01413.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2284-2291. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. ; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society . 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25, pt B):2985-3023. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.King DE, Mainous AG III, Carnemolla M, Everett CJ. Adherence to healthy lifestyle habits in US adults, 1988-2006. Am J Med. 2009;122(6):528-534. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mosca L, McGillen C, Rubenfire M. Gender differences in barriers to lifestyle change for cardiovascular disease prevention. J Womens Health. 1998;7(6):711-715. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1998.7.711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Connor Gorber S, Tremblay M, Moher D, Gorber B. A comparison of direct vs self-report measures for assessing height, weight and body mass index: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2007;8(4):307-326. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00347.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tylavsky FA, Sharp GB. Misclassification of nutrient and energy intake from use of closed-ended questions in epidemiologic research. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142(3):342-352. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jackson CL, Patel SR, Jackson WB II, Lutsey PL, Redline S. Agreement between self-reported and objectively measured sleep duration among white, black, Hispanic, and Chinese adults in the United States: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Sleep. 2018;41(6). doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Other Baseline Sleep Characteristics by Exposure to ALAN While Sleeping

eTable 2. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping and Prevalent Obesity, Weight Gain and Incident Obesity, With Further Adjustment for Confounders That Could Also Be Mediators of Associations Between ALAN Exposure at Night and Obesity

eTable 3. Comparison of Baseline Characteristics Between Those With and Without Body Mass Index Estimates at Follow-up

eTable 4. Prevalence Ratios and 95% CIs for the Association Between Other Sleep Characteristics and Measures of Prevalent Obesity

eTable 5. Relative Risks and 95% CIs for Other Sleep Characteristics, Subsequent Weight Gain, and Incident Obesity

eTable 6. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping and Incident Obesity (BMI≥30.0) Stratified by Selected Factors

eTable 7. Adjusted Relative Risks and 95% CIs for the Joint Association of ALAN Exposure, Leisure Time Physical Activity, and Healthy Eating Index–2015 With Subsequent Weight Gain of ≥5 kg and Incident Obesity

eTable 8. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping and Subsequent Weight Gain Using Percent Increase in BMI as a Continuous Variable

eTable 9. Comparison of Baseline Characteristics Between 2 Categories (Clusters) of Women With Television in Room

eTable 10. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping, Subsequent Weight Gain, and Incident Obesity Including Adjustment for Categories (Clusters) of Women With Television in Room

eTable 11. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping, Subsequent Weight Gain and Incident Obesity, After Excluding Women Who Responded “Yes” to Waking Up for Any Reason Every Night or Most Nights (n = 26 849)

eTable 12. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping, Subsequent Weight Gain, and Incident Obesity, After Excluding Women Who Reported Taking Naps

eTable 13. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping, Subsequent Weight Gain, And Incident Obesity With Inverse Probability Weighting to Account for Loss to Follow-up

eTable 14. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping, Subsequent Weight Gain, And Incident Obesity in Analysis Limited to 1 Randomly Selected Woman per Sibship (n = 39 188)

eTable 15. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping and Sleep Hours

eFigure. Association Between ALAN Exposure While Sleeping, Subsequent Weight Gain, and Incident Obesity