Abstract

The aim of this article was to study a case report of full mouth rehabilitation in a severally periodontally compromised patient in which 18 single piece basal implants were inserted and functionally loaded with both maxillary and mandibular cement retained fixed partial denture. Basal implants were loaded immediately, and excellent results were obtained. Bone loss was measured and values were recorded immediately after implant placement and after 6 months. Basal implants are used to support single and multiple unit restorations in the upper and lower jaws. They can be placed in the extraction sockets and also in the healed bone. Their structural characteristics allow placement in the bone that is deficient in height and width. Basal implants are the devices of the first choice, whenever (unpredictable) augmentations are part of an alternative treatment plan. The technique of basal implantology solves all problems connected with conventional (crestal) implantology.

Keywords: Basal implant, full-mouth rehabilitation, immediate loading

INTRODUCTION

Rehabilitation of partially and completely edentulous patients with implant-supported prosthesis has become a widely accepted treatment option.[1,2] The conventional Branemark system involves loading of the implants after 4–6 months of placement. This obvious disadvantage of the procedure leaves the patient with no teeth or with a removable temporary prosthesis, and hence, many patients, at times, do not choose this option at all. Dental implants, when placed in the basal bone, can be immediately loaded with teeth, as this bone is very strong, never gets resorbed throughout the life, and forms the stress-bearing part of our skeleton.[3] Since the cortical walls around the extraction site are stable at the time of extraction, placement of implants into fresh extraction sockets is more successful than placement after few months.[4] There are two different approaches for immediate loading of dental implants. First one is on the principle of compression screw, whereas the other is on the cortical anchorage of thin screw implants (bicortical screw [BCS]).[5]

The conventional crestal implants are indicated in situations when an adequate vertical bone supply is given. These crestal implants function well in patients who provide adequate bone when treatment starts, but prognosis is not good as soon as augmentations become part of the treatment plan. Augmentation procedures tend to increase the risks and costs of dental implant treatment as well as the number of necessary operations. Patients who have severely atrophied jaw bones paradoxically receive little or no treatment, as long as crestal implants are considered the device of the first choice.[6]

Conventional crestal implantology

In crestal implantology, implants are referred to as crestal-type implants if they are inserted into the jaw bone coming from the crestal alveoli and whose main load-transmitting surfaces are vertical. The traditional implants use the alveolar bone – this type of bone is lost after teeth are removed and decreases throughout the life as function reduces. It is standard practice to insert screws at least 10–13 mm in length in the anterior segment of the mandible because this part of the mandible usually offers sufficient vertical bone. However, in patients with very little available vertical bone, crestal implants are contraindicated.

Basal implantology

Basal implantology is also known as bicortical implantology or just cortical implantology. It is a modern implantology system which utilizes the basal cortical portion of the jaw bones for retention of the dental implants which are uniquely designed to be accommodated in the basal cortical bone areas. The basal bone provides excellent quality cortical bone for retention of these unique and highly advanced implants. Because basal implantology includes the application of the rules of orthopedic surgery, the basal implants are also called as “orthopedic implant” to mark a clear distinction between them and the well-known term “dental implant.” These basal implants are also called as lateral implants or disk implants.

History of the basal implants

First single-piece implant was developed and used by Dr. Jean-Marc Julliet in 1972. Because no homologous cutting tools are produced for this implant, its use is fairly demanding.

In the mid-1980s, French dentist, Dr. Gerard Scortecci, invented an improved basal implant system completed with matching cutting tools. Together with a group of dental surgeons, he developed disk implants. Since the mid-1990s, a group of dentists in Germany have developed new implant types and more appropriate tools, based on the disk-implant systems. These efforts then gave rise to the development of the modern basal osseointegrated implant or lateral basal implants.

Rationale of using basal implants

Teeth are present in less dense bone portions of the jaw bones called the alveolar bone. This is also known as the crestal bone of the jaw. The less dense alveolar or crestal bone gradually starts getting resorbed and recedes once the teeth are lost. The bone which ultimately remains after regression of the alveolar bone following loss of teeth is the basal bone which lies below the alveolar bone.

This basal bone is less prone to bone resorption and infections. It is highly dense, corticalized, and offers excellent support to implants. The conventional implants are placed in the crestal alveolar bone which comprises bone of less quality and is more prone to resorption.

The basal bone is less prone to bone resorption because of its highly dense structure. The implants which take support from the basal bone offer an excellent and long-lasting solution for tooth loss. At the same time, load-bearing capacities of the cortical bone are many times higher than those of the spongious bone. Indications and contraindications of basal implants are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Indications and contraindicaations of basal impalnts

| Indications | Contraindications |

|---|---|

| 1. All kinds of situations when several teeth are missing or have to be extracted | 1. Medical conditions: There are a number of medical conditions that preclude the placement of dental implants. Some of these conditions include recent myocardial infarction (heart attack) or cerebrovascular accident (stroke), immunosuppression (a reduction in the efficacy of the immune system) |

| 2. When the procedure of two-stage implant placement or bone augmentation has failed | 2. Medicines: Drugs of concern are those utilized in the treatment of cancer, drugs that inhibit blood clotting and bisphosphonates (a class of drugs used in the treatment of osteoporosis) |

| 3. All kinds of bone atrophy i.e. in case of very thin ridges, insufficient buccolingual thickness,insufficient bone height |

CASE REPORT

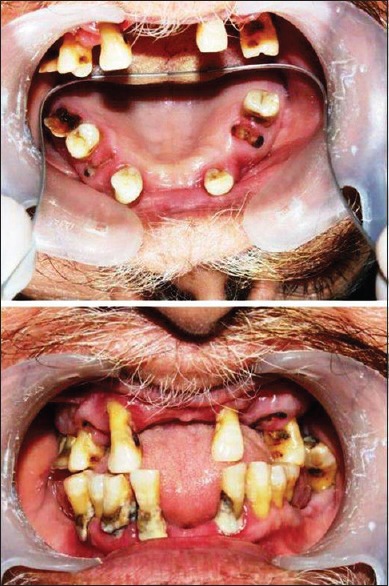

A 60-year-old male having normal gait and stature reported to the Department of Oro-Maxillofacial Prosthodontics, Crown and Bridge, and Oral Implantology with the chief complaint of inability to eat properly. Intraoral examination revealed that the patient had 16 teeth present which were severely periodontally compromised [Figures 1 and 2]. On clinical examination, it was observed that all the teeth were periodontally compromised (Grade III mobile). There was no significant medical history. Various treatment options included removable complete denture after total extraction, a conventional implant-supported fixed prosthesis (after augmentation procedures), a conventional implant-supported overdenture (after augmentation procedures), or a basal implant-supported fixed partial denture. The patient decided to have his treatment done in minimum time by the least traumatic and fixed option. Thus, we chose to rehabilitate the patient's mouth with a basal implant-supported fixed partial denture. This case report highlights the use of single-piece immediate implants (18 BCS) (Simpladent) in a full-mouth rehabilitation patient. A routine blood examination was done for the patient, and the results were found to be within normal limits. Local infiltration (Biocaine 21.3 mg lignocaine, India) was given. No mandibular block was administered to ensure the response of mandibular nerve. The remaining teeth were extracted atraumatically, and curettage was done followed by copious irrigation with povidone-iodine. Then, the implants were placed using a flapless immediate procedure [Figure 3].

Figure 1.

Preoperative intraoral view

Figure 2.

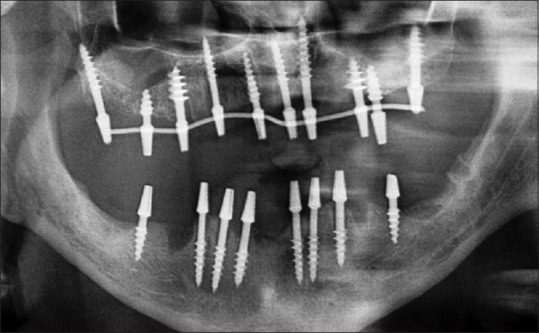

Preoperative radiographic view

Figure 3.

Postoperative radiographic view

Maxillary and mandibular impressions were made using additional silicone impression material, and tentative jaw relations were recorded using Aluwax. On the 2nd day, after the adjustment of metal framework in the patient's mouth and completion of successful metal try-in, definitive intermaxillary records were made. On the 3rd day, all the implants were functionally loaded with both maxillary and mandibular cement-retained metal-ceramic fixed partial denture, providing bilateral balanced occlusion [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Prosthesis in situ

DISCUSSION

Immediate loading of basal implants can be done, when they are placed in the dense cortical bone, as they attain high primary stability there. Therefore, they are more predictable than before, though there are high chances of crestal bone loss. Since the remodeling of the bone starts within 72 h and weakens the peri-implant bone structures, rigid splinting of the metal framework should be done as early as possible. The splinting distributes the masticatory forces from the bone around the implants to other cortical areas as well. This procedure and its principles are known in traumatology.[6] Ten implants were placed flaplessly in the maxillary jaw engaging the basal bone, using handgrip instruments. Out of ten BCS implants, four were placed in the maxillary anterior region engaging the nasal floor, as these were the recently extracted infected sockets and the remaining six were placed bilaterally in the tuberopterygoid region in the maxillary arch. This region provides more stability than anchorage offered by any other part of the maxillary region.[7] The eight implants were placed in the mandibular arches. Since the bone height was not sufficient in the mandibular right posterior region, one BCS implant was placed engaging the lingual cortical plate, bypassing the mandibular nerve. The remaining seven BCS implants were placed in the recently extracted infected sockets.[8] About 100% success rate can be achieved if BCS implants are used along with an appropriate immediate load protocol.[9] The BCS implants are smooth surface implants which have aggressive threads and can be placed in already infected sockets. We can achieve excellent primary stability along the vertical surfaces of BCS implants with no need for corticalization. Hence, they can be used for both immediate placement and immediate loading.[10]

CONCLUSION

Basal implants are used to support single- and multiple-unit restorations in the upper and lower jaws. They can be placed in the extraction sockets and also in the healed bone. Their structural characteristics allow placement in the bone that is deficient in height and width. Basal implants are the devices of the first choice, whenever (unpredictable) augmentations are part of an alternative treatment plan. The technique of basal implantology solves all problems connected with conventional (crestal) implantology. It is a customer-oriented therapy, which meets the demands of the patients ideally. Yes, this technique is being practiced by some leading implantologist in India, but the very thought of coming out of our comfort zone and trying a new system of implant makes many dentists hesitant.[8]

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Creugers NH, Kreulen CM, Snoek PA, de Kanter RJ. A systematic review of single-tooth restorations supported by implants. J Dent. 2000;28:209–17. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(99)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang RE, Lang NP. Ridge preservation after tooth extraction. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012;23(Suppl 6):147–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2012.02560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yadav RS, Sangur R, Mahajan T, Rajanikant AV, Singh N, Singh R. An alternative to conventional dental implants: Basal implants. Rama Univ J Dent Sci. 2015;2:22–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kopp S, Kopp W. Comparision of immediate vs. delayed basal implants. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2008;7:116–22. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Narang S, Narang A, Jain K, Bhatia V. Multiple immediate implants placement with immediate loading. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2014;18:648–50. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.142466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang TL, Raoumanas ED, Klokkevold PR, Beumer J. Biomechanics, treatment planning and prosthetic consider-ations. In: Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA, editors. Carranza's Clinical Periodontology. 10th ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2006. pp. 1167–81. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heim D, Capo JT. Forearm, shaft. In: Rüedi TP, Buckley RE, Moran CG, editors. AO Principles of Fracture Management. Vol. 2. Stuttgart, New York: Thieme-Verlag; 2007. pp. 643–56. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tulasne JF. Osseointegrated fixtures in the pterygoid region. In: Worthington P, Branemark PI, editors. Advanced Osseo-Integration Surgery: Applications in the Maxillofacial Region. Chicago, Ill: Quintessence Publishing; 1992. pp. 182–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ihde S, Ihde A, editors. Munich, Germany: The International Implant Foundation Publishing; 2011. Immediate Loading. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah S, Ihde A, Ihde S, Gaur V, Konstantinovic VS. The usage of the distal maxillary bone and the sphenoid bone for dental implant anchorage. CMF Implant Dir. 2013;8:3–12. [Google Scholar]