Abstract

Background & objectives:

Pediococcus pentosaceus has been reported to cause clinical infections while it is being promoted as probiotic in food formulations. Antibiotic resistance (AR) genes in this species are a matter of concern for treating clinical infections. The present study was aimed at understanding the phenotypic resistance of P. pentosaceus to macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLSB) antibiotics and the transfer of AR to pathogens.

Methods:

P. pentosacues isolates (n=15) recovered from fermented foods were screened for phenotypic resistance to MLSB antibiotics using disc diffusion and microbroth dilution methods. Localization and transferability of the identified resistance genes, erm(B) and msr(C) were evaluated through Southern hybridization and in vitro conjugation methods.

Results:

Four different phenotypes; sensitive (S) (n=5), macrolide (M) (n=7), lincosamide (L) (n=2) and constitutive (cMLSB) (n=1) were observed among the 15 P. pentosaceus isolates. High-level resistance (>256 μg/ml) to MLSB was observed with one cMLSB phenotypic isolate IB6-2A. Intermediate resistance (8-16 μg/ml) to macrolides and lincosamides was observed among M and L phenotype isolates, respectively. Cultures with S phenotype were susceptible to all other antibiotics but showed unusual minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of 8-16 μg/ml for azithromycin. Southern hybridization studies revealed that resistance genes localized on the plasmids could be conjugally transferred to Enterococcus faecalis JH2-2.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The study provides insights into the emerging novel resistance patterns in P. pentosaceus and their ability to disseminate AR. Monitoring their resistance phenotypes before use of MLS antibiotics can help in successful treatment of Pediococcal infections in humans.

Keywords: Antibiotic resistance, conjugation, Pediococcus pentosaceus

Pediococcus pentosaceus is a facultative anerobe, homofermentative, Gram-positive cocci belonging to the lactic acid bacteria (LAB) andwidely used in food fermentations1,2,3. The role of P. pentosaceus in causing infections is a matter of debate as it is often isolated with other organisms or causes mild infections4. It has been identified as an opportunistic pathogen in immunocompromised patients5 and this pathogenic trait of P. pentosaceus can create challenges in treating human infections as these are intrinsically resistant to glycopeptide group of antibiotics4. With the emerging reports on the detection antibiotic resistance (AR) genes in food-borne bacteria, the safety of commercially available LAB cultures has become a prerequisite with AR6. The anticipated problem is that foodborne bacteria might contain naturally occurring AR genes that could be ultimately transferred to human pathogens in the gut when ingested3. European Food Safety Authority also recommends that only probiotic strains which do not show resistance to antibiotics are considered safe for human and animal purpose7.

Although new antibiotics have been evolved, of macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLSB) superfamily antibiotics are still in use for human infections and as animal growth promoters8,9. Hence, the development of resistance to these antibiotics is a cause of concern8,10. In addition, various novel resistance phenotypes being observed in pathogenic11 and food-borne12 bacterial species have complicated the treatment of human infections.

Acquired resistance to erythromycin (ERY) among LAB species such as Lactobacillus and Enterococcus along with human pathogens8 has been described. Further, the treatment of MLSB-resistant human pathogens are difficult to treat due to the emergence of novel mechanisms evident through unusual phenotypes11,12. Although ERY resistance (ERr) is commonly observed among food LAB8, but Pediococcus species has shown no resistance to ERY among P. pentosaceus isolates1,13,14,15. In our previous study conducted on ERY and tetracycline (TET) resistance genes evaluated by PCR in LAB from various fermented foods, we have reported the presence of erm(B), msr(C) and several tet genes in P. pentosaceus cultures16. This study was undertaken to characterize the phenotypic MLSB heterogenicity, determine the localization and transferability of the identified resistance genes [erm(B), msr(C)] in P. pentosaceus isolates.

Material & Methods

Bacterial isolates & growth conditions: Fifteen P. pentosaceus isolates obtained from naturally fermented food (idli and dosa batter), dairy product-curd (dahi) and fermented dry sausage16 identified by biochemical and molecular characterization were included in this study. The E. faecalis strain JH2-2 was donated by Dr Charles MAP Franz, Federal Research Centre for Nutrition and Food, Institute of Hygiene and Toxicology, Karlsruhe, Germany. All the isolates were grown at 37°C in deMan, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) and/or brain heart infusion (BHI) broth or agar (HiMedia, Mumbai, India). Bacterial pure cultures were maintained in 40 per cent glycerol at −80°C. The isolates were sub-cultured twice before use. These experiments were conducted at Microbiology & Fermentation Technology department, CSIR-Central Food Technological Research Institute, Mysuru.

Antibiotic susceptibility: The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for clindamycin (CLD), azithromycin (AZI), lincomycin (LIN), spiramycin (SPI), clarithromycin (CLA) and pristinamycin (PRI) were determined by microbroth dilution method in MRS medium17. The plates were incubated at 37°C in ambient air. MICs of CLD were also defined in the presence of sub-inhibitory concentrations of ERY12. A double disc diffusion test with CLD (2 μg) and ERY (15 μg) discs was performed on MRS agar as described earlier12. The CLD resistant (CLDR) isolates were subjected to modified Hodge test for detection of lincosamide nucleotidyltransferase (Lnu) activity12. All the antibiotics either in powder form or discs were procured from HiMedia.

Isolation of DNA & detection of clindamycin resistance gene by PCR: The genomic DNA from test cultures was isolated using phenol-chloroform method as described earlier18. The isolated DNA was used as a template in PCR amplification reaction for lnu(A) and lnu(B) gene using the primers lnu(A)-F-5’- GGTGGCTGGGGGGTA GATGTATTAACTGG-3’ and lnuA -R-5’- GCTTCTTTTGAAATACATGGTATTTT TC GATC-3’ or lnuB-F-5′-CCTACCTATTGTTTGAA-3′ and lnuB-R-5′-ATAAC GTTAC TCTCCTATTC-3′19. The reaction mixture was composed of 5 pmol of each forward and reverse primers, 0.2 mM dNTPs mix (Bengaluru GeNei), 1× PCR buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 2.5 mM MgCl2 (Merck, Bengaluru), 4 μl containing 10 ng of genomic DNA as template and 1 μl containing 3U of Taq DNA polymerase (Sigma). PCR analysis was carried out as follows: 35 cycles of amplification including 30 sec of denaturation at 94°C, 40 sec of annealing at 44°C (lnuA) and 55 °C lnu(B) and 40 sec of elongation at 72°C.

Plasmid isolation & Southern hybridization: Isolation and purification of plasmids were performed12 and plasmids were analyzed on 0.7 per cent agarose gel. The separated plasmids were transferred to a Hybond-N + Nylon membrane (Sigma) using the downward capillary transfer technique12. The DNA bound to the membrane was hybridized with purified PCR products of erm(B) and msr(C), labelled with digoxygenin. Hybridization and detection were performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Roche Chemicals, Germany).

Conjugation experiment & evaluation of transconjugants: The transferability of ERr genes was determined in P. pentosaceus isolates, by in vitro conjugation using filter mating as described earlier20. Two isolates, IB4-2A and IB6-2A with M and cMLSB phenotypes respectively, were selected as donor isolates and the E. faecalis JH2-2 [resistant to rifampicin (RIF)] as the recipient. Conjugation experiments were performed with the donor/recipient ratios of 1:1, 10:1 and 50:1. At the end of the mating period, cells from the membrane filters (plate mating) were scraped off and suspended in 1 ml of the peptone physiological saline solution. Serial ten-fold dilutions of the above suspensions were prepared, and appropriate dilutions were spread onto BHI agar plates containing ERY (10 μg/ml) and RIF (50 μg/ml) as selective agents. The plates were incubated at 37°C and examined for colonies (transconjugants) after 24, 48 and 72 h. The donor and the recipient cell counts were enumerated by plating the dilutions on appropriate selective medium for donor (10 μg/ml of ERY) and recipient (50 μg/ml of RIF). The frequency of the resistance transfer was evaluated by the number of transconjugants/donor cells. The mating experiments were conducted three times in duplicates, and an average of the frequency values was reported. Transconjugants obtained were verified by comparing their fingerprints with that of donor and recipient isolates obtained by random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD)-PCR using M-13 primers employing a colony PCR approach12.

Results

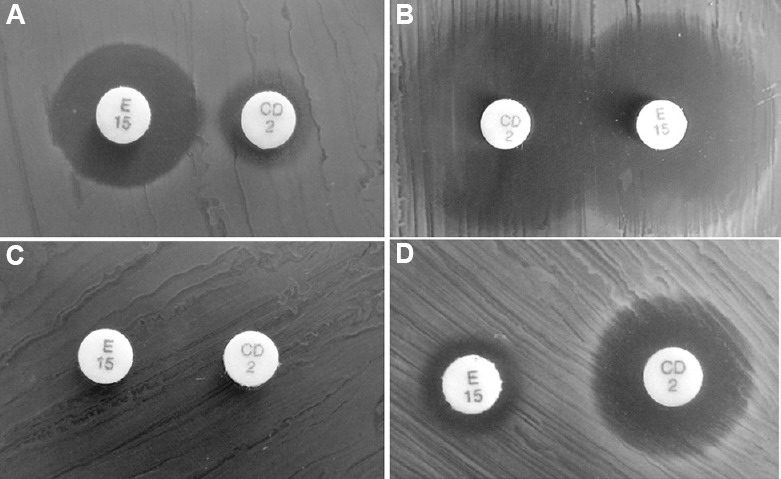

The P. pentosaceus isolates were subjected to CLD (2 μg) and ERY (15 μg) double disc test to determine their resistance phenotype. Among the 15 isolates tested, four distinct phenotypes were detected (Table). Five isolates were assigned to sensitive (S) phenotype which exhibited larger zones around ERY and CLD disks (Fig. 1). In contrast, one isolate showed no zone of inhibition for both the antibiotics and was designated cMLSB phenotype. Other two discrete non-inducible phenotypes observed were M and L phenotype (Fig. 1). Seven isolates with M phenotype showed intermediate sensitivity to CLD and resistance to ERY. Two isolates designated L phenotype displayed resistance to CLD and intermediate sensitivity to ERY.

Table.

Macrolides, lincosamides and streptogramin B phenotypes and minimum inhibitory concentrations (µg/ml) among Pediococcus pentosaceus

| Phenotype | n | AZI | CLA | CLI | LIN | SPI | PRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Es Cs | 5 | 8-16 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 2 | <1 |

| M | 7 | 8 | 2-4 | <1 | <1 | 8-16 | <1 |

| L | 2 | 8 | 2-4 | 8-16 | 16 | 8 | <1 |

| cMLSB | 1 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 |

ES CS, erythromycin and clindamycin sensitive; M, macrolide; L, lincosamide; cMLSB, constitutive-macrolide, lincosamide and streptogramin B phenotype; AZI, azithromycin; CLA, clarithromycin; CLI, clindamycin; LIN, lincomycin; SPI, spiramycin; PRI, pristinamycin

Fig. 1.

Evaluation of phenotypic MLSB heterogenicity in Pediococcus pentosaceus isolates. The double disc diffusion was performed using erythromycin disc ER15 (15 μg) and clindamycin disc CD 2 (2 μg) (A) Lincosamide (L) phenotype [Erythromycin sensitive (ERYS) and cindamycin intermediate resistant (CLDIR)]; (B) Sensitive (S) phenotype (ERYS and CLDS); (C) cMLSB phenotype (ERYR and CLDR); (D) M phenotype: (ERYIR) and (CLDS); MLSB, macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B; cMLSB, constitutive-macrolide, lincosamide and streptogramin B phenotype.

The distribution of MIC values for the tested antibiotics is summarized in the Table. High-level resistance to all the antibiotics was observed for the isolate IB6-2A, the sole cMLSB phenotypic strain. Isolates with S phenotype showed susceptibility to all the antibiotics but displayed MIC values of 8-16 μg/ml toward the synthetic 15-membered ring macrolide, AZI. Isolates with M phenotype demonstrated resistance to all macrolides while remained susceptible to lincosamides. In comparison, isolates with L phenotype showed resistance to lincosamides as well as low-level resistance to macrolides and spiramycin. Pristinamycin was found to be active against all isolates except, IB6-2A. In addition to the MIC test performed, the resistance profile of CLD was evaluated for the M phenotype isolates (n=7) after treating them with sub-inhibitory concentrations (induction) of ERY. However, no changes in the MIC values were observed upon induction.

Pediococcus pentosaceus lack lnu(A) or lnu(B) gene: To evaluate the genetic background of CLD resistance observed in isolates with L (n=2) and cMLSB (n=1) phenotypes, the antibiotic inactivation test was performed using CLD-sensitive Micrococcus luteus ATCC 9341. None of the cultures showed characteristic cloverleaf inhibition zone. In addition, the test isolates did not show any positive PCR amplification for either lnu(A) or lnu(B) genes.

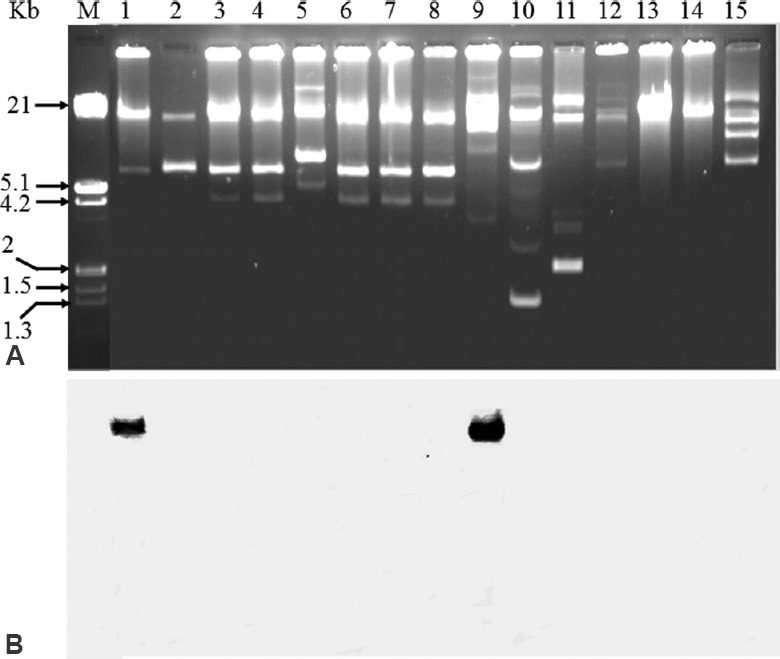

Localization of erm(B) & msr(C) genes: From P. pentosaceus cultures, the plasmids demonstrated their presence with different sizes ranging from 1.3 to >21 kb (Fig. 2A). Southern hybridization was performed with erm(B) and msr(C). Although the PCR results were positive for erm(B) and msr(C) in 12 and eight isolates respectively16, the Southern hybridization studies resulted positive for erm(B) and msr(C) only in two isolates (IB4-2A and IB6-2A) (Fig. 2B) with the isolated plasmids.

Fig. 2.

Southern hybridization with undigested plasmids of Pediococcus pentosaceus isolates against erm(B) gene probes. (A) Plasmids; (B) Southern blot analysis of plasmids hybridized with internal segments of erm(B) gene obtained by PCR and labelled with digoxigenin. Lane M: HindIII digested λ-DNA marker; lanes 1 to 15: P. pentosaceus isolates IB4-2A, IB4-2B, IB3-3, 8, B-1, IB3-1A, IB3-1B, IB3-2, IB6-2A, DB3-E4, DB3-STR3B, CHS-3E, 3, 4, IB2-1, respectively. The isolates IB4-2A and IB6-2A in lanes 1 and 8 respectively were positive for erm(B). The same isolates were also found positive for msr(C) with similar localization (data not shown). The localization of these genes was found on high molecular weight plasmids.

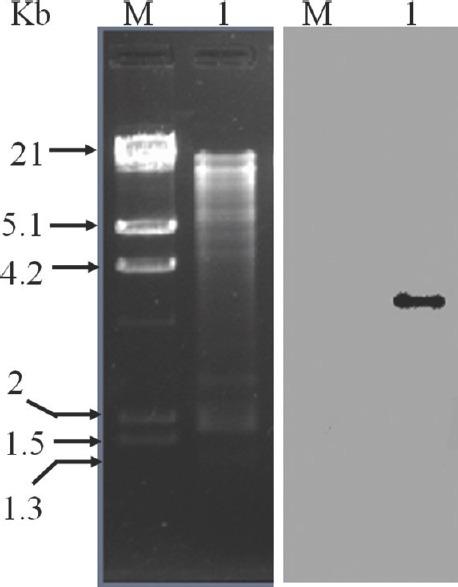

Transfer of erm(B) to Enterococcus faecalis JH2-2: Among all the P. pentosaceus isolates, two cultures (IB4-2A and IB6-2A) confirmed for erm(B) and msr(C) were investigated for their ability to transfer the genes to E. faecalis JH2-2 by in vitro conjugation. Among the three-different donor/recipient ratios, conjugation was observed with 50:1 combination and was successful with the sole cMLSB isolate, IB6-2A with a transfer frequency of 1 × 10−6/ donor cells. Confirmation of the transconjugant's identity was carried out by RAPD-PCR analysis revealing a banding pattern similar to that of the recipient and completely different from the donor isolate (data not shown). Genotypic characterization of the transferred resistance markers in transconjugants by PCR showed positive results only for erm(B). Plasmid profiling of the recipient (E. faecalis JH2-2) showed no transfer of plasmid from the donor isolate. The PCR results of erm(B) gene transfer was substantiated with Southern hybridization results when conducted with the digested chromosomal DNA of the recipient (Fig. 3). These results indicated the possible association of erm(B) gene with transposons. The ERr transfer was also validated with the performance of ‘D’ zone test where, all the selected transconjugants showed cMLSB phenotype and presented higher MIC values (128 μg/ml) for ERY.

Fig. 3.

Localization of erm(B) gene in transconjugant Enterococcus faecalis JH2-2 and antibiotic transferability of P. pentosaceus. Southern blot analysis of the total genomic DNA from E. faecalis JH2-2 digested with BamHI and hybridized with internal fragment of erm(B) gene obtained by PCR and labelled with digoxigenin. Lane M: HindIII digested λ-DNA marker; lane 1: BamHI digested total genomic DNA of transconjugant E. faecalis JH2-2 after conjugation (left). Positive Southern hybridization of erm(B) probe with the digested DNA fragment (right) indicating the transfer of erm(B) gene from P. pentosaceus IB6-2B isolate to E. faecalis JH2-2 during conjugation.

Discussion

Acquisition of ERr methylase genes (erm gene) confers resistance to MLSB antibiotics21. Expression of MLSB resistance can be constitutive (cMLSB) or inducible (iMLSB). In the later, the mRNA becomes active in presence of lower concentrations of macrolides and induces resistance to CLD. By contrast, in constitutive expression, active methylated mRNA is produced even in the absence of an inducer10. The cMLSB resistant phenotype was evident with one isolate that showed no zones of inhibition around the two antibiotic discs used. This characteristic phenotype was substantiated with high-level resistance to all the MLS antibiotics used.

P. pentosaceus has been shown to be susceptible to MLS antibiotics14. In our study, the five P. pentosaceus isolates with S phenotype were expected to be sensitive to all MLSB antibiotics considered. However, discrepancies were observed between this sensitive phenotype and MIC values for AZI (8-16 μg/ml). Further evaluation of genes that confer resistance specific to macrolides need to be investigated.

Besides the target modification, active efflux (due to drug pumps) which reduces intracellular antibiotic concentration is characterized with 14- and 15- membered macrolide resistance20. This was found to be one of the major resistances to macrolide antibiotics and associated with M phenotype22,23. To verify that M phenotype observed was not due to altered iMLSB phenotype, the CLD MIC was determined in the presence of sub-inhibitory concentrations of ERY. The results indicated unaltered CLD MICs which confirmed M phenotype in P. pentosaceus isolates. In contrast to M phenotype, two isolates displayed L phenotype that was comparable to that shown in Enterococcus species in our previous study12. However, the CLD inactivation test specific for LIN resistance genes was negative. Such results may be due to unidentified resistance genes prevailing in bacteria or due to changes in the existing erm genes11.

The double disc diffusion test (D zone test) being a useful guide to interpret the presence of MLS resistance genotypes24 is restricted to only pathogens and not for investigations in either LAB or probiotics. Previous studies conducted on MLS resistance in pathogenic bacteria reported that the disc diffusion test could be used to predict the genotype25. This was evident in our earlier study where one isolate with cMLSB was found to harbour erm(B)16. However, CLD not being an inducer or a substrate for efflux pump10, the two L phenotype isolates did not show any CLD inactivation phenotype or lnu(A) or lnu(B) genes. Such complexity of CLD resistance and ERY sensitive phenotype was observed previously in enterococci12 and in Staphylococcus agalactiae11. Pediococcus isolates frequently exhibit one or more ATP-binding cassette-type multidrug resistance26. Thus, it could be hypothesized that the observed phenotype with unexplained resistance patterns could be due to other efflux pump mechanisms or undefined novel mechanisms.

In LAB, including P. pentosaceus, plasmid associated resistance genes possibly spread to other more harmful bacteria5. This was evident with the transfer of erm(B) gene from IB6-2B to E. faecalis JH2-2 indicating the considerable potentiality of P. pentosaceus isolates in transferring AR genes to human pathogens. Although plasmids could be identified in these test isolates, we could detect the localization of resistance genes on plasmids only in two isolates. These results showed that majority of the isolates carried the erm(B) and msr(C) genes on the chromosomal DNA and suggested their association with transposons. More insights on this aspect could be gained by considering a large number of isolates from various sources. The same isolates although were found positive for TET resistance genes in our preliminary study16, we could not determine the localization of the tet genes in their genome. These findings provide emerging complex condition in characterization of AR and thus depend on basic phenotypic tests.

In conclusion, the results of our study supported the presence of diverse MLS resistance mechanisms justified by rapid variations in resistance phenotypes. The disc diffusion along with susceptibility tests may facilitate in identifying novel MLS resistance mechanisms. Monitoring of resistance phenotypes before the use of MLS antibiotics can help in effective and successful treatment of pediococcal infections.

Acknowledgment:

Authors thank the Director, CSIR-CFTRI, Mysuru, for providing the necessary facilities and for kind approval for the publication of this study (PMC reference No: PMC/2015-16/43).

Footnotes

Financial support & sponsorship: Authors acknowledge the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi, for financial support (AMR/24/2011-ECD-1). The first author (SCRT) acknowledges the ICMR for the grant of ICMR-SRF fellowship.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Danielsen M, Simpson PJ, O’Connor EB, Ross RP, Stanton C. Susceptibility of Pediococcus spp. to antimicrobial agents. J Appl Microbiol. 2007;102:384–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shukla R, Goyal A. Probiotic potential of Pediococcus pentosaceus CRAG3: A new isolate from fermented cucumber. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2014;6:11–21. doi: 10.1007/s12602-013-9149-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma P, Tomar SK, Goswami P, Sangwan V, Singh R. Antibiotic resistance among commercially available probiotics. Food Res Int. 2014;57:176–95. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suh B. Resolution of persistent Pediococcus bacteremia with daptomycin treatment: Case report and review of the literature. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;66:111–5. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steven LP, Yanina P. A case report of Pediococcus pentosaceus bacteremia successfully treated with daptomycin. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2014;22:e1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Courvalin P. Antibiotic resistance: The pros and cons of probiotics. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38(Suppl 2):S 261–5. doi: 10.1016/S1590-8658(07)60006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.EFSA. Scientific opinion on the safety and efficacy of Pediococcus pentosaceus (DSM 12834) as a silage additive for all species. EFSA J. 2011;9:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thumu SC, Halami PM. Acquired resistance to macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin antibiotics in lactic acid bacteria of food origin. Indian J Microbiol. 2012;52:530–7. doi: 10.1007/s12088-012-0296-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaheer R, Cook SR, Klima CL, Stanford K, Alexander T, Topp E, et al. Effect of subtherapeutic vs. therapeutic administration of macrolides on antimicrobial resistance in Mannheimia haemolytica and enterococci isolated from beef cattle. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:133. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leclercq R. Mechanisms of resistance to macrolides and lincosamides: Nature of the resistance elements and their clinical implications. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:482–92. doi: 10.1086/324626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Srinivasan U, Miller B, Debusscher J, Marrs CF, Zhang L, Seo YS, et al. Identification of a novel keyhole phenotype in double-disk diffusion assays of clindamycin-resistant erythromycin-sensitive strains of Streptococcus agalactiae. Microb Drug Resist. 2011;17:121–4. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2010.0040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thumu SC, Halami PM. Phenotypic expression, molecular characterization and transferability of erythromycin resistance genes in Enterococcus spp. isolated from naturally fermented food. J Appl Microbiol. 2014;116:689–99. doi: 10.1111/jam.12386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tankovic J, Leclercq R, Duval J. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Pediococcus spp. and genetic basis of macrolide resistance in Pediococcus acidilactici HM3020. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:789–92. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.4.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zarazaga M, Sáenz Y, Portillo A, Tenorio C, Ruiz-Larrea F, Del Campo R, et al. In vitro activities of ketolide HMR3647, macrolides, and other antibiotics against Lactobacillus, Leuconostoc, and Pediococcus isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:3039–41. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.12.3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rojo-Bezares B, Sáenz Y, Poeta P, Zarazaga M, Ruiz-Larrea F, Torres C, et al. Assessment of antibiotic susceptibility within lactic acid bacteria strains isolated from wine. Int J Food Microbiol. 2006;111:234–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thumu SC, Halami PM. Presence of erythromycin and tetracycline resistance genes in lactic acid bacteria from fermented foods of Indian origin. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2012;102:541–51. doi: 10.1007/s10482-012-9749-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CLSI Document M11-A6. 6th ed. Wayne: CLSI; 2004. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of anaerobic bacteria. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mora D, Fortina MG, Parini C, Daffonchio D, Manachini PL. Genomic subpopulations within the species Pediococcus acidilactici detected by multilocus typing analysis: Relationships between pediocin AcH/PA-1 producing and non-producing strains. Microbiology. 2000;146(Pt 8):2027–38. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-8-2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lozano C, Aspiroz C, Sáenz Y, Ruiz-García M, Royo-García G, Gómez-Sanz E, et al. Genetic environment and location of the lnu(A) and lnu(B) genes in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and other staphylococci of animal and human origin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2804–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gevers D, Huys G, Swings J. In vitro conjugal transfer of tetracycline resistance from Lactobacillus isolates to other Gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;225:125–30. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00505-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woods CR. Macrolide-inducible resistance to clindamycin and the D-test. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:1115–8. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181c35cc5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giovanetti E, Brenciani A, Burioni R, Varaldo PE. A novel efflux system in inducibly erythromycin-resistant strains of Streptococcus pyogenes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:3750–5. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.12.3750-3755.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhong P, Shortridge VD. The role of efflux in macrolide resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 2000;3:325–9. doi: 10.1054/drup.2000.0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waites K, Johnson C, Gray B, Edwards K, Crain M, Benjamin W., Jr Use of clindamycin disks to detect macrolide resistance mediated by ErmB and MefE in Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates from adults and children. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1731–4. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.5.1731-1734.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steward CD, Raney PM, Morrell AK, Williams PP, McDougal LK, Jevitt L, et al. Testing for induction of clindamycin resistance in erythromycin-resistant isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:1716–21. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.4.1716-1721.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haakensen M, Vickers DM, Ziola B. Susceptibility of Pediococcus isolates to antimicrobial compounds in relation to hop-resistance and beer-spoilage. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:190. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]