Abstract

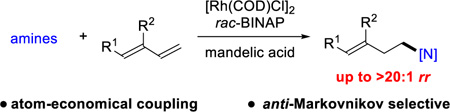

We report a Rh-catalyzed hydroamination of 1,3-dienes to generate homoallylic amines. Our work showcases the first case of anti-Markovnikov selectivity in the intermolecular coupling of amines and 1,3-dienes. By tuning the ligand properties and Brensted acid additive, we find that a combination of rac-BINAP and mandelic acid is critical for achieving anti-Markovni- kov selectivity.

Graphical Abstract:

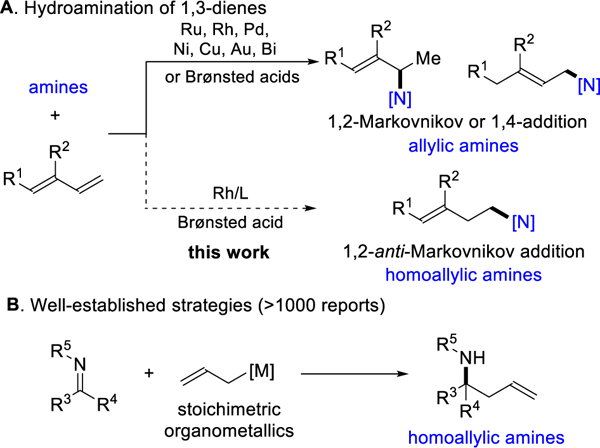

Coined in the 19th century, the concept of Markovnikov selectivity1 remains relevant today in classifying and developing regiose-lective transformations of olefins, including hydroamination.2 While hydroamination of alkenes typically furnishes the Markov-nikov product,3 there have been breakthroughs in reversing the re-gioselectivity to obtain the anti-Markovnikov isomer.4 However, the intermolecular hydroamination of 1,3-dienes5 has been limited to producing allylic amines through 1,2-addition or 1,4-addition, presumably due to the intermediacy of a stabilized π-allyl-metal (Figure 1A, top).6 Homoallylic amines are valuable synthetic building blocks that are typically generated by coupling imines to organ-ometallic reagents (Figure 1B).7 As a complement to using stoichiometric organometallics, we aimed to use simple dienes by developing a catalytic and regioselective hydroamination (Figure 1A, bottom). Herein, we disclose the first intermolecular hydroamination of 1,3-dienes to proceed with anti-Markovnikov selectivity.8,9 Our Rh-catalyst transforms conjugated dienes into homoallylic amines with high regiocontrol and atom economy.10

Figure 1.

Inspiration for anti-Markovnikov hydroamination of 1,3-dienes for synthesis of homoallylic amines

Our laboratory recently rendered the hydroamination of 1,3-dienes enantio- and regioselective. In this previous study, we generated allylic amines by using a [Rh(COD)OMe]2/JoSPOphos catalyst and triphenylacetic acid additive. 6m,11 In this communication, we focused on achieving a 1,2-anti-Markovnikov addition for the synthesis of homoallylic amines.

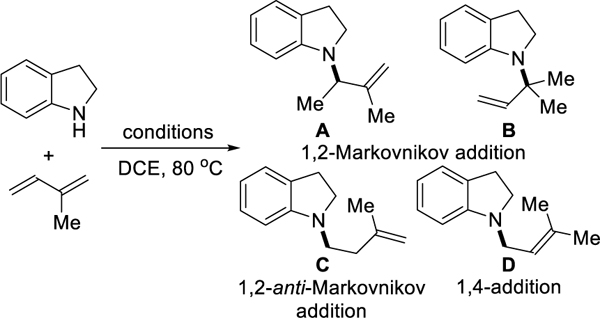

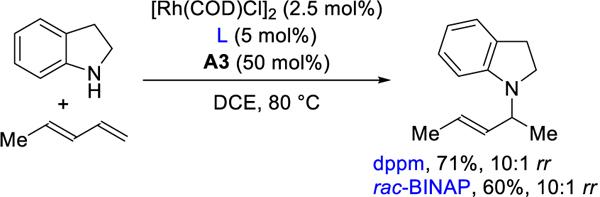

To begin this study, we chose indoline and isoprene as coupling partners. Isoprene, a common building block for polymers,12 derives from thermal cracking of naphtha/oil and biosynthesis by many organisms.13 We aimed to transform this feedstock into the corresponding homoallylic amine by studying the effects of biden-tate phosphine ligand and acid combinations. Table 1 summarizes our most relevant findings. Due to its use in alkyne hydroamination, phthalic acid was chosen as the initial acid for screening different bisphosphine ligands.14 When using dppm, a small bite angle ligand,15 we observe 1,2-Markovnikov addition product A as the major product (entry 1). Increasing the bite angle of the ligand decreases the reactivity and regioselectivity, leading to mixtures of A, B, C, and D (entries 2–4). Switching to a ferrocene-backbone ligand, dppf, we observed homoallylic amine C as the major product in 33% NMR yield (entry 5). When using rac-BINAP as ligand, the yield and regioselectivity of homoallylic amine C increases to 74% and 19:1 rr by 1H NMR analysis (entry 6). Rh(COD)2SbF6 and [Rh(COD)OMe]2 pre-catalyst give similar results with [Rh(COD)Cl]2 (entry 7 and 8). In accordance with Hartwig’s observations, the use of palladium as the catalyst yields 1,4-addition product D as the major isomer (entry 9).6b These results showcase an intermolecular hydroamination of isoprene where regioselectiv-ity is controlled by catalyst choice.16

Table 1.

Catalyst and Acid Effects on Regioselective Hydroamination of Isoprenea

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | pre-catalyst | ligand | acidb | yield (%)c | rr(A:B:C:D)d |

| 1 | [Rh(COD)CI]2 | dppm | A2 | 71 | 15:<1:<1:1 |

| 2 | [Rh(COD)CI]2 | dppe | A2 | 20 | 2:2:1:4 |

| 3 | [Rh(COD)CI]2 | dppp | A2 | 14 | 2:1:1:3 |

| 4 | [Rh(COD)CI]2 | dppb | A2 | <10 | ND |

| 5 | [Rh(COD)CI]2 | dppf | A2 | 33 | <1:<1:5:1 |

| 6 | [Rh(COO)CI]2 | rac-BINAP | A2 | 74 | <1:<1:19:1 |

| 7 | Rh(COD)2SbF6 | rac-BINAP | A2 | 71 | 1:1:>20:1 |

| 8 | [Rh(COD)OMe]2 | rac-BINAP | A2 | 69 | 1:1:>20:1 |

| 9 | Pd(PPh3)4 | none | A2 | 84 | 1:1:1:>20 |

| 10 | [Rh(COD)Cl]2 | rac-BINAP | none | NR | ND |

| 11 | [Rh(COD)Cl]2 | rac-BINAP | A1 | 17 | 1:1:>20:1 |

| 12 | [Rh(COD)CI]2 | rac-BINAP | A3 | 81 | 1:1:>20:1 |

| 13 | [Rh(COD)Cl]2 | rac-BINAP | A4 | 79 | <1:<1:13:1 |

Reaction conditions: indoline (0.1 mmol), isoprene (0.5 mmol), [M] (5 mol%), ligand (5 mol%), acid (50 mol%), DCE (0.2 mL), 24 h.

pKa in DCE and pKa in water in parenthesis.

1H NMR yields of major isomer using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as the internal standard.

Regioselectivity determined by 1H NMR analysis of reaction mixture.

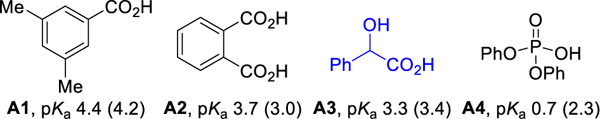

With the optimal ligand in hand, we investigated the effect of the acid additive. No product was observed in the absence of acid (entry 10). Diphenyl phosphate was successfully used to form C-C bonds in the hydrofunctionalization of alkynes.17 Therefore acids with similar pKa to diphenyl phosphate and phthalic acid were examined. As pKa values are solvent dependent,18 the pKa of the acids in DCE were determined using UV-vis spectroscopy.19,20a In general, higher yields are obtained with stronger acids (entries 11–13); mandelic acid (A3) gives 81 % yield and the best regioselectivity.20b

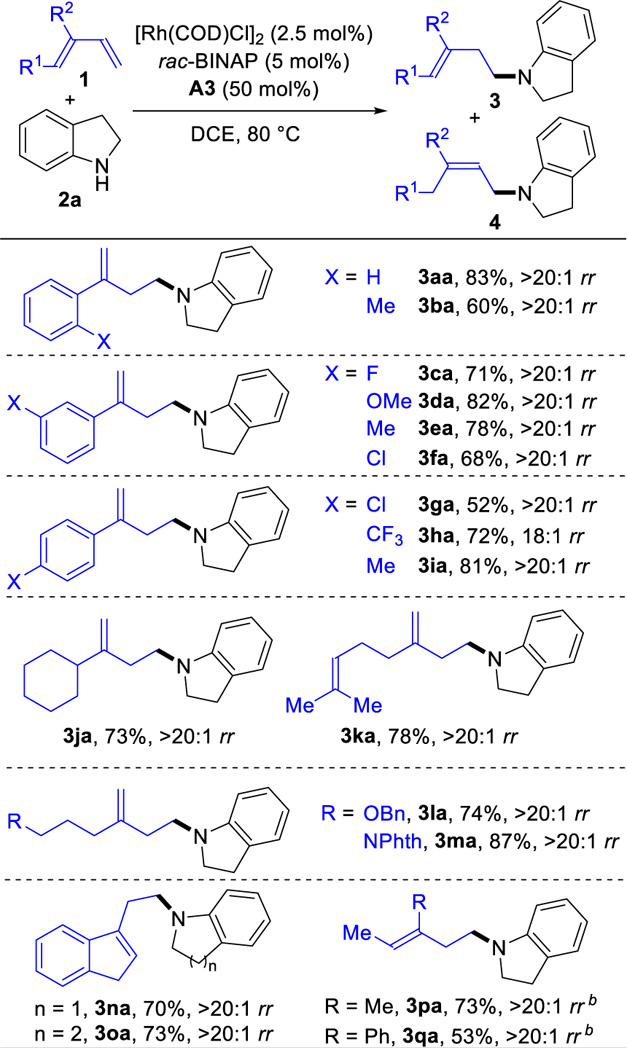

With this protocol, we examined the coupling of various 1,3-dienes 1 with indoline 2a (Table 2). In general, the hydroamination proceeds with 18:1 to >20:1 regioselectivities and 52–83% yields for various 2-aryl-1,3-butadienes (3aa-3ia). Substrates with an electron-donating group on the aryl ring show slightly higher reactivity than those with an electron-withdrawing group. When the aryl ring is ortho-substituted, the yield is lowered to 60% (3ba). In the case where the aryl ring contains an electron-withdrawing tri-fluoromethyl group (3ha), the regioselectivity is 18:1 rr. The transformation also proceeds with alkyl substituted dienes. 2-Cyclo- hexyl-1,3-butadiene undergoes hydroamination with 73% yield (3ja). Myrcene, a readily available monoterpene, furnishes the homoallylic amine (3ka) in 78% yield and >20:1 rr. The hydroamination proceeds efficiently for substrates bearing ether and amide groups and provides the corresponding products in 74% yield (3la) and 87% yield (3ma) with >20:1 regioselectivities.

Table 2.

Anti-Markovnikov Hydroamination of Various 1,3-Dienesa

|

Reaction conditions: 1 (0.3 mmol), 2a (0.2 mmol), [Rh(COD)Cl]2 (2.5 mol%), rac-BINAP (5 mol%), A3 (50 mol%), DCE (0.4 mL), 80 °C, 15 h. Isolated yields. Regioselectivity ratio (rr) is the ratio of 3 to 4, which is determined by 1H NMR analysis of reaction mixture.

Using Rh(COD)2SbF6 (5.0 mol%) instead of [Rh(COD)Cl]2.

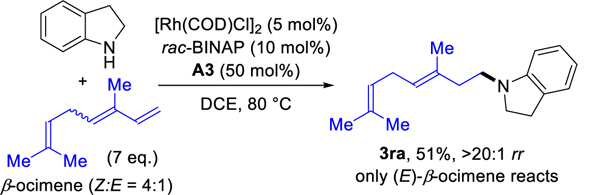

Transformations of 1,2-disubstituted dienes also proceed well. Hydroamination of the fused ring substrates provide the homoallylic amines in 70% and 73% yields (3na and 3oa) with >20:1 regioselectivities. In addition, we obtain the homoallylic amines 3pa and 3qa from acyclic 1,2-disubstituted dienes in 53% and 73% yields with >20:1 regioselectivities by using Rh(COD)2SbF6 as precatalyst. When using the mixture of (Z)- and (E)-β-ocimene isomers, we observe that only the (E)-β-ocimene is transformed to give homoallylic amine (3ra) in 51% yield (7 equivalents diene used); (Z)-β-ocimene is unreacted (eq 1).

|

(1) |

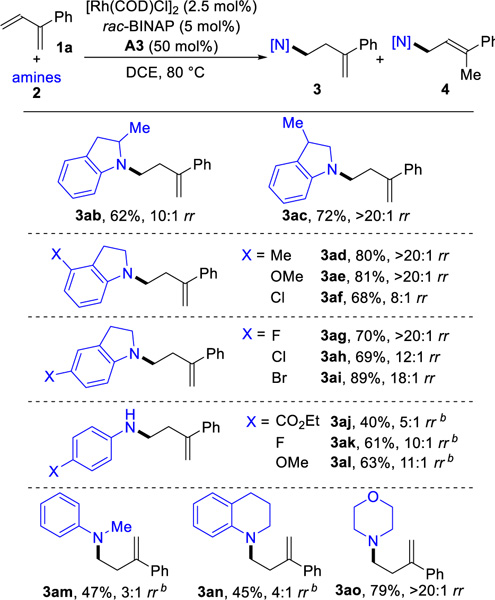

Next, we examined the hydroamination of 2-phenyl-1,3-butadi-ene 1a with different amines 2 (Table 3). Indolines provide the hydroamination products (3ab-3ai) with 62–89% yield and 8:1 to >20:1 anti-Markovnikov selectivity. Indolines with electron-donating groups show higher regioselectivities than those with electron-withdrawing groups. The hydroamination of sterically hindered 2-methyl-indoline gives homoallylic amine (3ab) in 62% yield and 10:1 regioselectivity. Anilines bearing either electron-donating or electron-withdrawing groups both undergo hydroamination with 40–63% yields (3aj-3al). Hydroamination of the acyclic amine N-methylaniline yields the product 3am in 47% yield with 3:1 regioselectivity. 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline can be used for hydroamination with 45% yield and 4:1 selectivity for the anfi-Mar-kovnikov product (3an). Under our hydroamination conditions, morpholine is an effective amine partner and provides the homoal-lylic amine 3ao in 79% yield with >20:1 rr. Identifying a catalyst that can enable coupling with more challenging amines (such as primary alkyl amines and acyclic dialkyl amines) is still an ongoing challenge that needs to be solved.20c

Table 3.

Anti-Markovnikov Hydroamination Using Various Aminesa

|

Reaction conditions: 1a (0.3 mmol), 2 (0.2 mmol), [Rh(COD)Cl]2 (2.5 mol%), rac-BINAP (5 mol%), A3 (50 mol%), DCE (0.4 mL), 80 °C, 15 h. Isolated yields. Regioselectivity ratio (rr) is the ratio of 3 to 4, which is determined by 1H NMR analysis of reaction mixture.

Using Rh(COD)2SbF6 (5 mol%) instead of [Rh(COD)Cl]2.

We reason that the anti-Markovnikov selectivity results from a synergy between the substrate and catalyst structure. To probe the mechanism, we studied the kinetic profile for coupling 1,3-diene 1a and indoline 2a. When using [Rh(COD)Cl]2 pre-catalyst, we observed a half order dependence on rhodium pre-catalyst, which suggests that breaking up the Rh-dimer is a slow step under our optimal conditions. Because this catalyst resting state is off-cycle, we switched to using monomeric Rh(COD)2SbF6 pre-catalyst to probe the mechanism further.

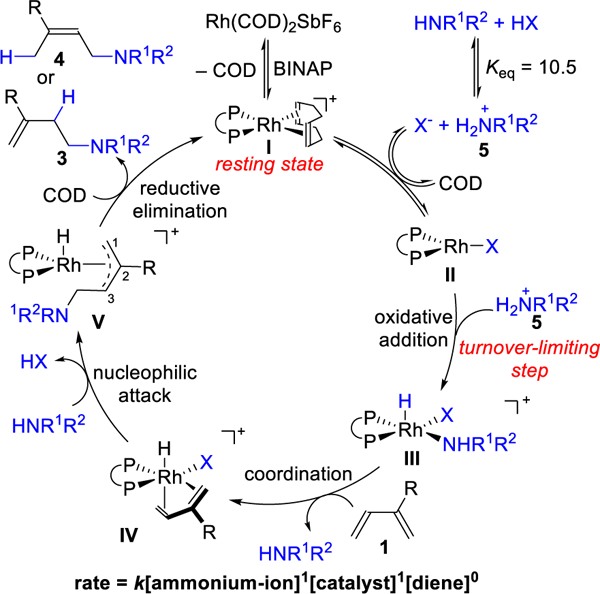

On the basis of both literature precedence and the following mechanistic studies, we propose the mechanism depicted in Figure 2. Rhodium pre-catalyst reacts with BINAP ligand to form the active catalyst I, which is the resting state as determined by 1H and 31P NMR. The amine and acid undergo proton transfer to form ammonium-ion 5 and carboxylate anion (X-). Using HypNMR,21 the equilibrium constant for this process was measured to be Keq=10.5.18 Ligand exchange of COD with carboxylate anion results in complex II. In the turnover-limiting step, the ammoniumion 5 oxidatively adds to the Rh(I)-complex II to generate Rh(III)-hydride III. In support of the proposed turnover-limiting step, we observe a first order dependence on the Rh-catalyst and a first order dependence on the ammonium-ion 5. Moreover, we see a zeroth order dependence on the diene, which means its involvement occurs after the turnover limiting step.20d

Figure 2.

Proposed mechanism for anti-Markovnikov selectivity

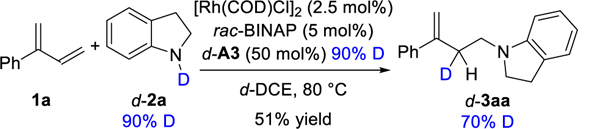

The 1,3-diene can exchange with the amine to form η4-Rh-hy-dride intermediate IV, which is analogous to a Co-hydride intermediate implicated in the hydrovinylation of 1,3-dienes.22 Because (E)-β-ocimene (and not the Z isomer) undergoes hydroamination (eq 1), we propose that s-cis conformation of the 1,3-diene is necessary for coordination to the catalyst.23 Due to the steric clash between the R substituent and the catalyst, the hydride insertion is disfavored. In line with this idea, we observe only Markovnikov addition using substrates bearing hydrogen at the 2-position, regardless of the catalyst used (eq 2). When the hydroamination was performed with deuterated indoline d-2a, the deuterium is incorporated into the 3-position of product 3, not the recovered diene (eq 3). This isotopic labeling result helps us rule out mechanisms that involve reversible diene insertion into the Rh-hydride.

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

In accordance with anti-Markovnikov hydroamination of al-kenes using directing groups,24 we imagine that the amine attacks the activated 1,3-diene from the less substituted position to generate Rh-π-allyl intermediate V. Reductive elimination of V at the 3-position gives homoallylic amine 3. This step is related to Rh-catalyzed alkyne or allene hydrofunctionalizations, which tend to favor the branched product after reductive elimination.14,17,25 We reason that electron rich amines improve regioselectivity by promoting reductive elimination at the 3-position rather than 1-position.

Hydroamination of conjugated dienes represents an attractive way to transform dienes into amine building blocks, but achieving regioselective hydroamination is challenging given the extended π-system. To date, there are few reports of functionalizing the terminal carbon of 1,3-dienes through 1,2-hydrofunctionalization.5b Modification of the substrate structure has been used to achieve challenging transformations, such as the regiodivergent arylboration of 1,3-dienes.26 Through key interactions between the catalyst and the 2-substitution of the substrate, we were able to achieve a 1,2-anti-Markonvikov hydroamination of dienes to access homoal-lylic amines. Future studies are warranted to better understand the origin of this regiocontrol. Insights from this communication will guide the invention of new diene hydrofunctionalizations.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Funding provided by UC Irvine, the National Institutes of Health (GM105938) and the National Science Foundation (CHE-1465263). We thank Materia Inc. for providing Grubbs catalyst C627, which was used to prepare 1,3-dienes 1a-1j.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Experimental procedures and spectral data for all new compounds (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- (1).Markownikoff W Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie. 1870, 153, 228. [Google Scholar]

- (2).For recent reviews see: (a) Müller TE; Hultzsch KC; Yus M; Foubelo F; Tada M Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 3795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Huang L; Arndt M; Gooßen K; Heydt H; Gooßen LJ Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).For select examples on Markovnikov hydroamination of al-kenes, see: (a) Kawatsura M; Hartwig JF J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 9546. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang Z; Du Lee S; Widenhoefer RA J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Reznichenko AL; Nguyen HN; Hultzsch KC Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 8984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zhu S; Niljianskul N; Buchwald SL J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 15746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Ickes AR; Ensign SC; Gupta AK; Hull KL J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 11256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Sevov CS; Zhou J; Hartwig JF J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 3200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).For select examples on anö’-Markovnikov hydroamination of alkenes, see: (a) Beller M; Trauthwein H; Eichberger M; Breindl C; Herwig J; Müller TE; Thiel OR Chem. Eur. J. 1999, 5, 1306. [Google Scholar]; (b) Utsunomiya M; Kuwano R; Kawatsura M; Hartwig JF J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 5608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ryu J-S; Li GY; Marks TJ J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 12584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Takaya J; Hartwig JF J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 5756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Rucker RP; Whittaker AM; Dang H; Lalic GJ Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 6571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Nguyen TM; Manohar N; Nicewicz DA Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 6198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Bronner SM; Grubbs RH Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Musacchio AJ; Lainhart BC; Zhang X; Naguib SG; Sherwood TC; Knowles RR Science 2017, 355, 727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).For recent examples on hydrofunctionalization of 1,3-dienes, see: (a) Zbieg JR; Yamaguchi E; McInturff EL; Krische MJ Science 2012, 336, 324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Saini V; O’Dair M; Sigman MS J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 608. For reviews, see: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hydrofunctionalization. In Topics in Organometallic Chemistry; Ananikov, V. P.; Tanaka, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, 2014; Vol. 343. [Google Scholar]; (d) McNeill E; Ritter T Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).(a) Armbruster RW; Morgan MM; Schmidt JL; Lau CM; Riley RM; Zabrowski DL; Dieck HA Organometal - lics 1986, 5, 234. [Google Scholar]; (b) Löber O; Kawatsura M; Hartwig JF J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 4366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Minami T; Okamoto H; Ikeda S; Tanaka R; Ozawa F; Yoshifuji M Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40,4501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Pawlas J; Nakao Y; Kawatsura M; Hartwig JF J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 3669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Brouwer C; He C Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Qin H; Yamagiwa N; Matsunaga S; Shibasaki MJ Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Johns AM; Liu Z; Hartwig JF Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 7259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Giner X; Nájera C Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Brinkmann C; Barrett AGM; Hill MS; Procopiou PA J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Banerjee D; Junge K; Beller M Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Goldfogel MJ; Roberts CC; Meek SJ J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 6227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Banerjee D; Junge K; Beller M Org. Chem. Front. 2014, 1, 368. [Google Scholar]; (m) Yang X-H; Dong VMJ Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 1774 For select examples of intramolecular hydroamination of 1,3-dienes, see: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Hong S; Kawaoka AM; Marks TJ J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 15878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (o) Shapiro ND; Rauniyar V; Hamilton GL; Wu J; Toste FD Nature 2011, 470, 245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (p) Dion I; Beauchemin AM Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 8233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).For select reviews on homoallylic amine synthesis by imine allylation, see: (a) Denmark SE; Fu J Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yus M; Gnzález-Gómez JC; Foubelo F Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 7774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).For intramolecular hydroamination of 1,3-dienes giving homoallylic amines, see: (a) Stubbert BD; Marks TJ J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 4253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yamamoto H; Sasaki I; Shiomi S; Yamasaki N; Imagawa H Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pierson JM; Ingalls EL; Vo RD; Michael FE Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 13311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).In general, functionalization of the distal carbon through 1,2-addition into terminal 1,3-dienes is rare, and Markovnikov selectivity is useful for distinguishing between these two modes of 1,2-addition.

- (10).Trost BM Science, 1991, 254, 1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).For a complementary approach using Pd-catalysis, see: Adamson NJ; Hull E; Malcolmson SJ J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 7180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).For recent review, see: Moad G Polym. Int. 2017, 66, 26. [Google Scholar]

- (13).For recent review, see: Ye L; Lv X; Yu H Metab. Eng. 2016, 38, 125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Chen Q-A; Chen Z; Dong VM J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 8392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).van Leeuwen PWNM; Kamer PCJ; Reek JNH; Dierkes P Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).For ligand-controlled regioselective hydrothiolation of al-kenes, see: Kennemur JL; Kortman GD; Hull KL J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 11914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Cruz FA; Dong VM J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).We thank reviewer 1 for suggesting we discuss pKa in DCE and the equilibrium between the amine and acid.

- (19).Seo M-S; Kim HJ Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 14190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).See Supporting Information for: (a) details on determination of pKa values.(b) a comprehensive list of acids evaluated (Table S1).(c) other amines that showed no reactivity (Figure S4).(d) details on mechanism studies.

- (21).Frassineti C; Ghelli S; Gans P; Sabatini A; Moruzzi MS; Vacca A Anal. Biochem. 1995, 231, 374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Sharma RK; RajanBabu TV J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 3295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).For conformational analysis of dienes, see: (a) Tai JC; Allinger NL J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976, 98, 7928 For coordination of s-cis-1,3-dienes to cobalt, see: [Google Scholar]; (b) Pünner F; Schmidt A; Hilt G Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Timsina YN; Biswas S; RajanBabu TV J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 6215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- (24).(a) Ensign SC; Vanable EP; Kortman GD; Weir LJ; Hull KL J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 13748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gurak JA Jr.; Yang KS; Liu Z; Engle KM J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 5805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).For review, see: Koschker P; Breit B Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Sardini SR; Brown MK J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 9823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.