Abstract

Objectives:

The foundational role culture and Indigenous knowledge (IK) occupy within community intervention in American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) communities is explored. To do this, we define community or complex interventions, then critically examine ways culture is translated into health interventions addressing AIAN disparities in existing programs and research initiatives. We then describe an Indigenous intervention based in the cultural logic of its contexts, as developed by Alaska Native communities. Yup’ik co-authors and knowledge keepers provide their critical and theoretical perspectives and understandings to the overall narrative, constructing from their Indigenous knowledge system, an argument that culture is prevention.

Conclusions:

The intervention, the Qungasvik (phonetic: qoo ngaz vik; tools for life) intervention, is organized and delivered through a Yup’ik Alaska Native process the communities term ‘qasgiq’ (phonetic: kuz-gik; communal house). We describe a theory of change framework built around the ‘Qasgiq Model,’ and explore ways this Indigenous intervention mobilizes aspects of traditional Yup’ik cultural logic to deliver strengths-based interventions for Yup’ik youth. This framework encompasses both an Indigenous knowledge (IK) theory-driven intervention implementation schema and approach to knowledge production. This intervention and its framework provide a set of recommendations to guide researchers and Indigenous communities who seek to create Indigenously-informed and locally sustainable strategies for the promotion of health and well-being.

“Qasgirarneq (qaz gee raar neq) has a meaning to encircle. In coming together around our youth in the ways of our ancestors, we are strengthening our collective spirit in an effort to cast the spirit of suicide and substance abuse out from our communities, forever.”

– Yup’ik Elder

The role of culture in health interventions focused on reducing disparities among American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) populations is now widely acknowledged as critical both to successful implementation and effectiveness (Bassett, Tsosie & Nannauck, 2012; Brown, Dickerson & D’Amico, 2016: Henry, et al., 2012; Goodman & De Beck, 2017; Wexler & Gone, 2012). Airhihenbuwa et al. (2013) advocate for a paradigm shift that recognizes that “to change negative health behaviors, one must first identify and promote positive health behaviors within the cultural logic of its contexts” (pg. 78, emphasis added). The central importance of culture and context as protective and promotional to health has also been recognized at the federal level. A U.S. Department of Health and Human Services report on suicide prevention among AIAN youth and young adults noted that “cultural continuity appears to be a strong protective factor against suicide” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010, p. 26).

This paper will first discuss the concept of culture, with a particular emphasis on the foundational role of Indigenous knowledge (IK) within community intervention in AIAN communities. Table 1 provides a brief overview of key terms and their definitions that will occur throughout the paper and are specific to the Yup’ik Indigenous knowledge system. For our present purpose, we define complex community interventions here through their emphasis on (a) community capacity development through community-engaged processes; (b) multi-level, or ecological and systemic perspectives on intervention and its implementation (c) primacy of community collaboration and empowerment; and (d) culture and cultural history as a resource and influence (Trickett et al., 2011). Next, we will critically examine ways culture is translated into health interventions addressing AIAN disparities through a review of existing programs and research initiatives. We then describe an Indigenous intervention based in the cultural logic of its contexts, as developed by one group of Alaska Native communities1. The Qungasvik (qoo ngaz vik; tools for life, http://www.qungasvik.org/preview/) intervention is organized and delivered through a Yup’ik Alaska Native process the communities term ‘qasgiq’ (qaz gik; men’s/communal house). We then describe a theory of change framework built around the ‘Qasgiq Model.’ The Qasgiq Model mobilizes aspects of traditional Yup’ik cultural logic within its local contexts to deliver strengths-based interventions for Yup’ik youth from within an Indigenous theory-driven intervention implementation schema. We conclude with recommendations for researchers and Indigenous communities working together to create more effective, Indigenously-informed and locally sustainable strategies to promote health and wellbeing.

Table 1:

Terms and Definitions

| • Indigenous knowledge (IK) | Unique world views and associated knowledge systems integrating core values, beliefs, and practices of the culture and its people. We capitalize “Indigenous” in accordance with the Alaska Native Studies Council Writing Style Guide. |

| • Qasgiq (Phonetic: kuz-gik) | A Yup’ik structure that traditionally housed the men and was used for communal activities and ritual events. |

| • Qasgiq Model | Term used to refer to a Yup’ik theory and intervention process to bring about community-level change and protection as part of the Qungasvik (Tools for Life) intervention. |

| • Qasgirarneq (Phonetic: qaz gee raar neq) | A variant of qasgiq that is a verb meaning to circle around or complete a cycle. |

| • Qungasvik (Phonetic: qoo ngaz vik) | Yup’ik sewing kit or small toolbox. Term used to refer to the preventive intervention approach developed by Yup’ik communities in southwest Alaska and defined as “Tools for Life.” |

| • Yuuyaraq (Phonetic: you ya raq) | The Yup’ik way of life. |

Culture, Cultural Models and Indigenous Knowledge in AIAN Health Interventions: Understanding and Using the Cultural Logic of Contexts in Prevention and the Promotion of Well-being

While discussion of the role of culture in intervention to address health inequities among AIAN groups is widespread in the current literature (Gone, 2013), many questions remain regarding specific processes in which culture informs the development, implementation, and evaluation of community interventions. Culture has traditionally referred to mores, folkways, traditions, ceremonies, values, norms, and structures designed to create meanings that are transmitted across generations. Most importantly, cultures reflect deep-seated epistemologies, values, and assumptions that shape how people understand phenomena, engage in social contexts, and go about daily activities. Accordingly, culture refers to “whole ontologies of being, hierarchies of values, and moral systems” (Kirmayer, 2012, p. 252). These ontologies provide a “shared ecologic schema or framework that is internalized and acts as a refracted lens through which group members ‘see’ reality” (Kawaga-Singer, Dressler, George, & Elwood, 2015, p. 29).

Indigenous Knowledge (IK)

One increasingly salient framing of culture focuses on the concept of IK. Barnhardt & Kawagley (2005) remind us that Indigenous peoples throughout the world have over millennia retained their unique world views and associated knowledge systems; these include core values, beliefs, and practices and represent “complex knowledge systems with an adaptive integrity of their own” (p. 9). The importance of IK to health and health-related community intervention is underscored by the World Health Organization (Durie, 2004). Their report emphasizes the holistic nature of IK and highlights four distinct but co-existing IK dimensions: spiritual, intellectual, physical, and emotional. Each of these dimensions has been found to be related to health and survival over time.

Emphasis on IK reinforces the larger concern about self-determination, cultural maintenance, and rejuvenation among varied Indigenous populations (Bohensky & Maru, 2011). Documenting such knowledge and the processes through which it is learned and transmitted can benefit not only self-determination of Indigenous people but can enrich a larger understanding of adaptive processes in human communities (Barnhardt & Kawagley, 2005). Battiste (2005) adds that “Indigenous Knowledge benchmarks the limitations of Eurocentric theory—its methodology, evidence, and conclusions—reconceptualizes the resilience and self-reliance of Indigenous peoples, and underscores the importance of their own philosophies, heritages, and educational processes” (p. 5).

It is important to emphasize that the same IK system is not necessarily shared across Alaska Native cultural groups, Yup’ik cultural groups, or even culturally similar communities in a particular region. For example, one cultural group residing in different communities may live their culture in different ways in response to different conditions and adaptive demands in their local ecologies. For example, Birman, Trickett, and Buchanan (2005) and Vinokurov, Trickett, and Birman (2016) found that culturally comparable adolescent and adult Jewish refugees from the former Soviet Union (FSU) developed different patterns of acculturation with respect to their culture of origin and American culture in response to living in communities that varied in ethnic density of FSU refugee families. Culturally comparable Yup’ik Alaska Native villages were similarly found to respond differentially in their approach to the development of a youth suicide and alcohol risk prevention program (Trickett, Trimble, & Allen, 2014). Because IK may differ across communities sharing the same culture (see also Donovan, Thomas et al., 2015), it becomes critically important to understand how broad cultural ways of life are currently being expressed locally when developing interventions.

In addition, differing groups within a community may construct some aspects of IK differently, or may place more importance on some kinds of IK than others. For example, the interpretation of shared knowledge may diverge depending on how it affects different people’s interests. This suggests that an emphasis on IK must confront issues of power not only between scientific and IK epistemologies, but also in terms of whose local knowledge counts when conceptualizing and designing interventions (Briggs, 2005; Sillitoe, 1998).

Indigenous Knowledge and Scientific Knowledge

An appreciation of how IK informs and shapes community interventions is of both scientific and social importance. In particular, the relationship of IK to scientific knowledge has received considerable attention. On the positive side, Durie (2004) suggests that addressing the science/IK interface can be a vital heuristic for improving health outcomes. Durie asserts that Indigenous researchers can have access to both scientific and Indigenous worlds of knowledge and, as such, can serve an invaluable boundary-spanning function. In like manner, Bohensky and Maru (2011) identify other processes that may mutually enrich the relationship between Indigenous and scientific knowledge. These processes can promote greater awareness of the cultural context in which integration of the Indigenous and scientific knowledge occurs and develop new criteria for evaluating knowledge gained in the intervention.

With respect to the specific contributions of IK in crafting community interventions, Gone (2016) delineates four domains: origins of problems, norms of well-being, approaches to treatment, and assessment of outcomes. Here, the centrality of historical trauma is reflected in origins of problems, and restoration of long-standing and local notions of selfhood and relationship norms emerge as intervention goals. Gone also suggests that Western science paradigms can be employed to increase information about the impact of IK-based practices, though these efforts may involve ethical issues related to disclosure of traditional practices (Gone, 2017).

While application of IK holds significant promise, Gone (2012) also suggests that approaches that seek to blend or integrate IK with intervention science may confront core epistemological incompatibilities. For example, the focus of intervention science privileges group outcomes, quantification, and generalizability. In contrast, IK is often grounded in deep respect for personal and individual experience, typically narratively portrayed. In addition, elements of IK can at times involve protected spiritual knowledge and levels of understanding not readily amenable to reductionistic approaches. Nadasdy (1999) and Hall (2015) caution that efforts to integrate these two sources of knowledge often ignore power issues between interventionists and communities that can result in work serving scientists more than Indigenous people. Thus, there is ongoing debate about the epistemological compatibilities and incompatibilities of IK and scientific knowledge and how they are reflected in the intervention. The present study contributes to this discussion by providing an example of one community’s efforts to ground an intervention in IK.

Indigenous Knowledge in AIAN Intervention Literature

There is clear consensus in the AIAN intervention literature that IK, variously labeled, is critical to respect and include when designing and conducting community interventions in tribal communities (Thomas, Rosa et al., 2011; Mohammed, Walters et al., 2012; Duran & Walters, 2004). However, within this literature, the meaning of IK varies in the degree to which culture occupies a fundamental role in theorizing, implementing, and evaluating the interventions. Okamoto et al. (2014) present a conceptual model for developing “culturally focused” interventions ranging from cultural adaptations of existing programs developed in other places and with other populations, to “culturally grounded” ones reflecting the deeper structures of local culture throughout the adaptation and implementation process. Such deep cultural grounding is most likely to be present in grassroots interventions built on the lived experience of the communities of concern, employing local rather than researcher-defined criteria for achieving goals (Whitbeck & Walls, 2012).

Indigenous knowledge and adapted interventions

The published literature provides differing examples of the varying roles of IK in intervention development, implementation, and evaluation. For example, Jobe et al. (2012) review five interventions to reduce cardiovascular risk in American Indian communities that all include local input on various aspects of research design, recruitment, implementation, and dissemination of results. While all projects are collaborative in terms of local inclusion and involvement in varied project components, the specific role of culture seems focused on respectful consideration of cultural influences rather than a more fundamentally cultural theory of the problem and solution. Further, it is unclear whether these interventions are locally developed projects or are based on adaptations of programs developed elsewhere.

Many projects have specifically described processes of adapting existing programs to be locally relevant and meaningful for AIAN communities. For example, LaFromboise and Howard-Pitney (1995) conducted a deep structure adaptation of the Life Skills Curriculum, a school-based suicide prevention program. The adaptation focused on skills training and psycho-education related to suicidal behavior appropriate for Zuni Pueblo adolescents in New Mexico. Over the course of a year, Zuni tribal members and teachers adapted the curriculum to reflect Zuni traditions and values (see LaFromboise & Lewis, 2008).

Goodkind et al. (2012) similarly report on a community-based cultural mental health intervention for youth in a tribal community in the American Southwest. The approach began with an adaptation of an evidence-based group intervention, Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS) and resulted in a four-part curriculum for adolescents heavily influenced by IK. The adaptation and resulting intervention was implemented by a team that included both tribal members and non-tribal local professionals well-known in the community. Drawing on the CBITS intervention, a local community advisory committee developed specific intervention components and named the intervention with a local word meaning Our Life to convey the spirit of positive cultural revitalization underlying the specific components.

Thomas et al. (2009; 2015) describe the collaboration between the University of Washington and two tribal communities to develop a curriculum for the Community Pulling Together: The Healing of the Canoe project. The project itself involved extensive tribal/university collaboration around varied community assessment tasks. These included advisory group formation and involvement, hiring of tribal members in key project roles, and project activities to build local capacity and educate researchers from outside the tribe about tribal history and culture. This extensive collaborative assessment ended with the selection and adaptation of a protocol previously developed by members of the research team for use with urban Native American adolescents. The goal of the adaptation was to “preserve core evidence-based treatment components of the prevention intervention while adding cultural content to enhance tribal-specific cultural elements” (Donovan et al., 2015, p.6). In this case, the focus of cultural content specifically enhanced the traditional practice of the canoe journey.

Another extensive example of an adaptation process was provided by Jumper-Reeves et al. (2014) in their description of the adaptation of the “keepin’ it REAL” program designed to prevent substance use/abuse. These authors use the “surface versus structural” distinction to describe how “interventions can be strengthened if they benefit from community insight and incorporate community theories of etiology and change” (Wallerstein & Duran, 2006, p. 318). They first describe differences between Indigenous and Western world views as manifested in the original intervention curriculum. They then identified American Indian cultural elements that altered the curriculum and how it was delivered.

Thus, many examples exist of how culture, and elements of IK may underlie and may be infused into existing models of preventive interventions in AIAN communities. Each of these examples stresses the importance of collaboration among participating parties alongside the development of processes and structure to ensure that local voices are heard. Each emphasizes the importance of respect and the development of trusting relationships over time. Though differing in emphasis, each recognizes the importance of drawing on and, in some instances, reclaiming cultural knowledge and history for the purposes of building strengths and resilience.

The Qasgiq Model: A Yup’ik Cultural Logic Model of Contexts

This paper is based on a view of IK as pervasive and fundamental to understanding the world view of individuals and communities in the cultural logic of AIAN contexts. IK is emergent through the process of the very formulation of local issues and potential solutions, as well as through the development of the relational processes that next form in order to gather and use local information. IK underlies the structure, content, and conduct of intervention activities, as well as the definition, meaning, and scope of processes and outcomes that are the focus of intervention. Thus, the present paper adopts a cultural logic modeling perspective to guide the content and processes of a participatory approach to community intervention.

The remainder of the paper presents a history of Qungasvik, an ecological, complex intervention that uses IK to frame intervention within the cultural logic of its context. First and foremost, the intervention is Indigenously driven and oriented around a Yup’ik cultural model of change. From a Western intervention perspective, this model might be described as a logic model, but it is more expansively based in the cultural logic of its context. The model also represents an Indigenous theory-driven intervention implementation process in that its process of implementation, assessment of outcomes, and dissemination of outcomes rests on Indigenous practices. Therefore, we define Indigenous intervention through these four characteristics: (a) Indigenous control, (b) Indigenous cultural model of change, (c) Indigenous theory-driven intervention implementation, and, (d) Indigenous approach to knowledge development.

Various aspects of the intervention have been described elsewhere (e.g. Allen, Mohatt, & Trickett, 2014; Qungasvik: http://www.qungasvik.org/preview/)), including the history of the cultural context and development of an Indigenous theory of protective factors with respect to suicide and alcohol abuse (Ayunerak, et al., 2014; Allen et al., 2014). Together, these papers describe the development of an Indigenous cultural model of change emerging from extensive life history discovery-based qualitative research (Mohatt et al., 2004). This model identified protective factors at the individual, family, and community level and provided the theoretical basis for the intervention. The papers go on to show how Indigenous control evolved over time through a CBPR intervention process that began with the establishment of local health priorities. This was followed by the development of an intervention to address these priorities (Rasmus, Charles, & Mohatt, 2014), then implementation in the intervention development community and dissemination of the intervention to other local communities.

The present paper builds on this previously published work by more fully describing mechanisms of Yup’ik culture and IK that are determined, by community consensus, to be protective against youth suicide and alcohol misuse. By focusing on the theory-driven implementation process in detail, we illustrate how Indigenous culture can be foundational in the community intervention implementation process.

Indigenous Theory-driven Intervention Implementation: The Qasgiq Model

The Qasgiq (men’s/communal house) Model is a primary conceptual driver in the implementation of the Qungasvik community preventive intervention. The term ‘qasgiq’ comes from qasgiqirayaq (qaz gee raar neq), which has as one of its possible meanings, ‘to encircle.’ In traditional Yup’ik culture, the qasgiq was a round, semi-subterranean structure. The structure was used as the primary living space for an extended kinship structure of men and boys during the winter months. In addition to being a living space, the qasgiq was also a central place for community gatherings, ceremonies and celebrations.

In its deeper cultural meaning, qasgiq in the Yup’ik language can be used as both a noun and verb. Qasgiq is a place, but it is also an action and a collective process. It is this latter meaning that continues to be relevant today, as the qasgiq structures themselves are no longer built or maintained, following the period of colonial contact and missionization that took place through much of the 20th century in southwest Alaska. Today in Yup’ik communities, qasgiq is a term commonly applied to gatherings, often taking place for important ceremonial purposes, such as the Yup’ik song and dance events, and for celebrations. Some communities will also “call a qasgiq” when an issue arises that needs collective input and action, such as when there is a tragedy (suicide, accidental death or injury), natural disaster (flooding, erosion) or local disturbance (illegal behavior, juvenile mischief).

In Yup’ik culture and cosmology every community has a qasgiq. This alludes to the ways the Qasgiq Model speaks to an important truth in all successful community-based health intervention efforts; every community has a local cultural process of coming together, of organizing its work, and of intervening effectively, and this element of community and culture transcends the realm of community problems. In Yup’ik communities, the qasgiq was always there; in times of joy as well as sorrow, it was continuous and was there every day. In this way, the qasgiq is also an Indigenous organizational structure guiding intervention implementation that, as a system, reflects and reproduces core Yup’ik principles, ideologies and theories.

At the core of the qasgiq, in structure and in function, is the circle and the cycle of life, death and rebirth. This process of encircling begins at conception and connects people to place and all life, corporeal and metaphysical, within it. This approach encompasses and has implications for both knowledge production and its associated theory of change. With respect to IK and knowledge development, Yup’ik knowledge is collective, relational and cyclical, and will continue its development through kinship-based cycles involving the social networks of ancestors to descendants. In a Yup’ik theory of change, no individual stands outside the circle. Hence, change can only be understood in relationship to others in the circle of family and community as represented within the qasgiq. As described in the next section, this has important implications for the nature of the intervention, understandings of the intervention change process, and intervention endpoints and outcomes.

History and Context: Defining the Yup’ik Cultural Logic of Contexts

The Yup’ik world changed rapidly and dramatically in the later 20th Century upon contact with groups of people from outside and distant cultures. The circle was broken when missionaries deemed the qasgiq an improper and immoral structure (Fienup-Riordan, 1994) and commissioned single-family homes to be built in accordance with Christian and Euro-American standards of family life and social organization. As the qasgiq was increasingly forbidden by outside religious authority as a functional center of Yup’ik community, the Yup’ik extended-family kinship structure became fragmented.

Permanent settlements were established around the churches, provisionary stores, and later, schools (Bjerregaard, 2001). These newly established communities brought newly fragmented family units from different extended kinship structures together, with no previous experience in living together in close and permanent proximity, into non-nomadic year-round dwellings. Some families steadfastly maintained their qasgiq structures through the 1960s and continued to spend a great deal of time at seasonal camps for fishing, trapping and hunting. However, by the mid-1970s, the last of these families were permanently settled into the new villages, and the last of the traditional qasgiq buildings became abandoned and no longer maintained. The ensuing 30 years brought additional dramatic changes. Some of these changes were positive, and included improvements to health care, access to electricity, running water, sewer, and electronic media, and the introduction of machines and other technological efficiencies. Other changes wrought ill effects on the people.

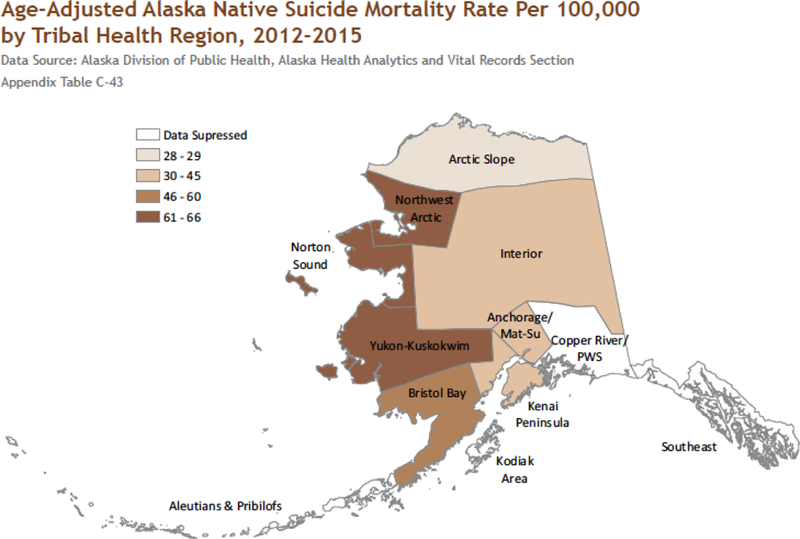

Epidemiological data on suicide among Alaska Native people show some of the worst outcomes from the rapid and imposed social changes. Rates on Alaska Native suicide began to be systematically collected in 1950, and show suicide was exceedingly rare and rates were quite stable from 1950 until 1965. However, from 1965–70, the rate doubled from 13/100,000 to 25/100,000, with most of the observed increase due to suicide among 15 to 25 year olds (Krauss, 1974). From 1970–74, the rate doubled again (Kraus & Buffler, 1979), and this continued every five years; from 1960–95, suicide rates increased approximately 500% (Brems, 1996). Suicide is currently the leading cause of death for Alaska Native men between the ages of 15 and 29 years old. Alcohol misuse and alcohol-related accidents, injuries and deaths also increased during this span of time, with alcohol associated with 60% of deaths by suicide (Allen, Levintoya, & Mohatt, 2011).

Every Alaska Native community has been impacted by suicide and alcohol abuse, but some regions, and some communities within these regions, are disproportionately impacted (Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium Epidemiology Center, 2017). Recent data from the Yukon Kuskokwim region of Alaska, in which the Qungasvik work is based, indicate a rate of 143.9 per 100,000 (Craig & Hull-Jilly, 2012), which is over ten times the U.S. general population rate of 13.26 per 100,000. Billy Charles (personal communication, 2017) observes that the beginning of this rise in the rate of Alaska Native suicide in the epidemiological data occurs around the time the qasgiq was closed in his community.

In the Qungasvik approach, the theory-driven intervention implementation process is based on Yup’ik Indigenous epistemologies and practices. When university researchers first arrived in the community, they were brought to a meeting with the Elders and official tribal and community leadership. Community members explained to them that it was customary when visitors came into the community for the people to gather in the qasgiq. From that initial visit, the qasgiq process would become the central organizing activity for the Qungasvik intervention. As the development and expansion of the intervention went on over the years, the qasgiq process would come to serve as the local theory driving the intervention implementation in other Yup’ik communities as the prevention trial expanded.

The qasgiq process describes a community action and is a key activity in the intervention implementation process. The qasgiq process brings people together in a traditional way in the context of a Yup’ik community. In the qasgiq there are no “chiefs” or formal officials, but instead everyone comes into the qasgiq with their own knowledge, experience and role. No one is potentially more or less valuable, but some sources of knowledge are more applicable depending on the nature of the need. In this way, IK took lead in the development of the Qungasvik intervention approach. Western knowledge, while now clearly an integral part of IK in a contemporary community context, took a supplementary role in the intervention development. The university researchers were invited to share the latest innovations from science and Western clinical practice with the community and Elders determined where synergies could result in stronger action and outcomes for youth.

Indigenous control requires a strong effort by the Elders of the community. In that first qasgiq described above, Elders identified those whose knowledge, experience and roles would guide the development and delivery of the suicide and alcohol misuse prevention activities. They also identified the population of focus, which would be youth 12 to 18 years of age, as well as the outcomes they wished to achieve–increased strengths and protections, and ultimately, increased reasons for life and reasons for sobriety. Subsequent meetings of the qasgiq in that first Yup’ik community (87 meetings to be precise) led to the identification of a formal intervention and research implementation process, based around qasgiq, to provide delivery of protective cultural experiences in the community for youth. The specifics of the development and implementation of these intervention activities are found in Rasmus, Charles, and Mohatt (2014). Fundamentals of the intervention implementation process include a three-year duration of sustained activities; with the first 9-month year focused on strengthening the community through qasgiq planning meetings and the other two years focused on delivery of a set of prevention activities; 12–18 activities are delivered per a 9-month period beginning in the fall and ending in the spring. Intervention activities are suspended over the summer months when subsistence activities take on urgent significance. Subsistence involves the majority of the adult and teenage youth who are engaged in securing salmon and other food resources to last the rest of the year.

In a Yup’ik cultural model, young people need to be exposed at the right time in their lives and their development to the values, teachings and practices that will give them the skills and confidence they need to live their yuuyaraq (you ya raq: way of life). The rapid social and environmental changes taking place in the Yup’ik communities, particularly in the last half century, have decreased exposure to these protections. Young people, while growing up in these communities, are being exposed to adversities and traumas not altogether unknown by their ancestors. However, they do so often without gaining the protective skills, cultural strengths, values, and connections that were traditionally provided through cultural practices, and needed to survive and to live a good life. Through the qasgiq process, key teachings from the culture were matched with key protective factors identified by Elders and community members and were validated through discussion with university partners (Allen, Mohatt, Fok., et al., 2014). The qasgiq process contextually privileged the Yup’ik IK, while allowing Western science and the research partners’ knowledge to contribute or aide when synergistic to the intervention goals.

The qasgiq process became an essential structure for achieving both the intervention and the research partnership goals. As the intervention research expanded to include additional Yup’ik communities, the qasgiq process took on an additional role in dissemination for a prevention trial study. It became necessary to translate the qasgiq process in a way that both communities, and grant funding research and service agencies would understand. The Qasgiq Model describes a community-level and cultural intervention implementation process in a Yup’ik theory of change. Below, we represent the Qasgiq Model in a series of process steps that mirror the process steps often included in Western-based conceptual logic models.

A Yup’ik Cultural Logic Model of Contexts

The first step (Figure 1) in the Qasgiq Model provides a historical context situating the subsequent steps in a schema of cultural continuity and change. This historicizing process step is a defining characteristic in an Indigenous Yup’ik logic model. Typically, in Western-based logic models, the process begins with recognizing or organizing current resources and identifying inputs based on gaps or needs in the contemporary context. Then the typical model proposes strategies and identifies desired or hypothesized outputs and outcomes resulting from the introduction of these new inputs and/or strategies. In an Indigenous Yup’ik model, the theory of change takes into account the historical context of the community. In the Qasgiq Model, this begins with recognizing the historical strengths and resilience of the community and the ancestors. The external view of the qasgiq (Figure 2), the literal source of the Qasgiq Model, shows how the qasgiq structure was once the center of the community. Qasgiq was a place to live and a place to learn important survival skills, and more broadly, to gain and share knowledge, practice and experience. Healing and ceremony were important occupations of the qasgiq, as evidenced by the fire, water and earth of the structure. These critical functions of the qasgiq were disrupted during the contact and settlement era. The Qasgiq Model emphasizes the process of revitalizing this important structure in a contemporary Yup’ik context by focusing on the symbolic meanings and functions of qasgiq that continue to exist outside of its physical structural form. In a Yup’ik theory of change, the functions of qasgiq, particularly those that reinforce or recreate collectivity, interdependence, equanimity and encircling or cycling (e.g. Fienup-Riordan, 1994) are important process steps to getting to youth wellness outcomes.

Figure 1:

Map of Alaska with regional suicide rates

Figure 2:

Exterior view of a traditional Yup’ik village, qasgiq center structure

In the next step in the Qasgiq Model, perspective visually moves inside of the qasgiq structure to examine the elemental symbols, resources, and strategies of the community intervention process. This step (Figure 3) shows the interior of a traditional qasgiq structure depicting important Yup’ik cultural symbols and elements, including the fire, the water, the window and the earthen floor. The four Yup’ik drums in the center depict the key process steps in the community intervention. The process moves from left to right with the far-left drum showing the historical progression of the qasgiq from being based entirely within kinship and community to reflect the changing social organization of Yup’ik communities with the introduction of Tribal, state and federal systems and structures. In the Yup’ik cultural model, the first step towards youth well-being and prevention is to rebuild or re-center the community around the qasgiq. Protective communities provide positive and strengthening experiences for young people. In a Yup’ik context, the qasgiq is a key community protective factor.

Figure 3:

Interior view of a traditional qasgiq, Qasgiq Model process steps (left to right)

In the first year of the Qungasvik intervention implementation, communities go through a qasgiq process that brings together the Elders, community members and organizational leaders, youth, and representatives from outside partner and service agencies. Reorganizing Yup’ik communities around qasgiq addresses the fragmentation and dislocation that has occurred post-contact with the settlement of kin groups into permanently occupied and federally-recognized Tribal villages.

Once the qasgiq has been firmly re-established with members identified by their partnership role in contributing to youth well-being, the next step involves the identification of Yup’ik cultural strengths and protective factors. The Qasgiq Model demonstrates the ways that Yup’ik communities conceptualize youth prevention as occurring at multiple levels with protection taking place within the community, families and individuals. The protective factors in the Qasgiq Model represent a synergistic alignment of Yup’ik IK translated into Western psychological terms. This translation took place in the qasgiq with Elders leading the negotiation of cultural equivalency between the Indigenous and Western terms. The protective factors listed in the Qasgiq Model are not meant to be exhaustive or inclusive of all Yup’ik protections and strengths but are meant to serve as examples that other Yup’ik communities can then build from and track in their own implementation process.

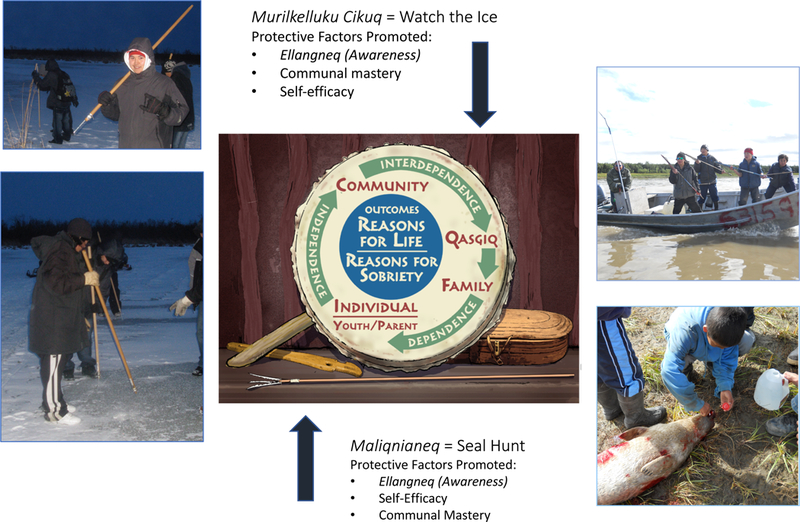

The third drum in the Qasgiq Model represents the Yup’ik community-driven contextual adaptation and delivery of intervention activities. This process step begins with a qasgiq meeting to reflect upon and identify the cultural teachings and activities that are most appropriate to the season, location, and status of the community. For example, if it is late summer or early fall time in a coastal community the qasgiq may select to take youth out seal hunting or fishing. If it is late fall or early winter in a tundra community it may be time to make ayaruq (eye yar uk: walking stick), or to set a fish trap, and learn at the same time about ice safety. There might also be the occurrence of adverse events that may inform the type of activities the qasgiq members select.

After selecting a set of activities, the qasgiq selects members of the community to provide the instruction and teachings for the activities. Some activities will involve Elders as storytellers and providers of teachings; others may involve strong hunters, tool makers, sewers, beaders, or those with skills in gathering of plants and foods from the tundra. After the Yup’ik experts have been identified, they will next gather in a work group and plan the activity. A key part of the work group planning involves the selection of protective factors that will be taught to young people as they engage in the activity. Other aspects of planning will take place at the work group, including choosing the day and time and identifying the supplies and safety conditions needed to provide a protective experience for the youth. The next step is the delivery of the activity led by the local prevention coordinators and community instructors. Finally, to complete the circle, the community meets again in the qasgiq to reflect on the activities and select the next set of cultural activities. The encircling process is marked by cycling back to the qasgiq to engage in reflexive discourse. The purpose is to document what worked and what can be learned from the activity, and of social capital building and partnership capacity development.

The fourth drum in the Qasgiq Model illustrates outcomes the Yup’ik communities have selected as most relevant in addressing disparities in youth suicide and alcohol misuse. The ultimate outcomes of reasons for life and sobriety are achieved when change takes place at the community level and protections are increased in individual youth and their families. Youth well-being goals are reached when communities demonstrate they have moved from a social organizational status of being fragmented and dependent on outside or external resources, to achieving independent decision-making and responsibility for action, and ultimately, to acknowledging the interdependence that is essential for a whole and healing community.

When communities undertake the Qasgiq Model process, they collectively provide opportunities for youth to engage in protective childhood experiences. These experiences lead to positive behavioral outcomes for youth who gain survival skills and build resilience as they learn about who they are as Yup’ik people. Figure 4 illustrates the interaction between two intervention activities, seal hunting and ice safety, and shows the linkage to these behavioral outcomes that are derived from participation of the community in planning and carrying out the work, and from youth participating in the activities.

Figure 4:

Qasgiq Model in action. Ice saftey (left) and seal hunting (right) build protection and contribute to outcomes at the community, family and individual levels.

Conclusion: Translating Cultural Models and Indigenous Knowledge into Health Interventions

A persistent problem in getting down to the Indigenous in health interventions is that in the past, providers and researchers have tended to come from outside of AIAN cultures and communities, and have remained rooted in their own cultural logic and theoretical epistemologies. The focus on “culture” in health intervention has too often been a shallow or surface translation describing more macro-level, formulaic, and ahistorical aspects of AIAN life. Increasingly, this focus is shifting towards understanding the role of Indigenous frameworks, paradigms and theories in the enactment of cultural teachings, practices and activities that construct and reinforce Indigenous identities. The increase in number and diversity of Indigenous peoples receiving advanced degrees in Western academic fields undoubtedly contributes to this focus.

The present paper places IK at the center of the intervention process. Indeed, in the Qasgiq Model case example, Yup’ik culture is prevention. The Qasgiq Model reflects Yup’ik IK about the ways that community can organize and work together to improve the lives and health of its members through self-determined and Indigenously controlled interventions. A distinguishing feature of Indigenous interventions, when compared with culturally-based or adapted approaches, is that the theory of change, service delivery system, and outcomes assessment derives from the cultural logic and social theories of the community and its people. Distinguishing ‘the Indigenous’ in a contemporary AIAN cultural context is an ongoing, sometimes contested, but always critical task for communities undertaking the negotiation, re-connection and persistence of a collective and individual Indigenous identity in a changed and changing world. Often this cultural logic element of IK is communicated as the collective core values and structural principles of the people. It is important to preserve, protect and pass on these unique cultural forms, particularly within a global health crisis that inequitably impacts upon diverse, disadvantaged and dislocated peoples.

While the need for and benefits of Indigenous interventions are clear, very few research studies have been undertaken to develop and test these intervemtions using scientifically rigorous methods. Alaska Native communities are small, remote, and culturally diverse. Interventions developed in one community, and in one cultural location, may not translate into other Alaska Native communities and contexts. Thus, scaling-up community-level interventions is a complex cultural process. Indigenous community control and initiation of the intervention research is a key factor in the Qungasvik/Qasgiq Model success story. Growing the Indigenous intervention means first growing Yup’ik and other Alaska Native self-determination in health care services and research. Dissemination of findings from both grassroots and sponsored research and service efforts is a critical next step for communities to gain more knowledge about strategies that are locally developed and controlled. In this way, community leaders can learn tools for advocacy and initiation of their own prevention efforts.

In conclusion, few efforts to date have been effective at reducing the burden of suicide and alcohol misuse in Yup’ik Alaska Native communities in the Yukon Kuskokwim Delta. In the context of critical, and at times even desperate need in the communities to address these problems, the Yup’ik Elders guiding the development of the Yup’ik cultural model approach instructed the local prevention team and the researchers to keep to the positive. They encouraged the team to teach the youth about their historical and inherited strengths as Yup’ik people. The Elders stressed the importance for young people to create a healthy relationship to their past as a way to build strengths within themselves today. The Elders chose to combat current adversity and problems resulting from these disruptions through a singular emphasis on the culture and its emphasis on the power of love to protect young people even through the darkest and most difficult of times. The Qungasvik prevention approach, through the Qasgiq Model, mobilizes community, cultural and historical strengths to build protection against suicide and alcohol misuse. When communities come together around their youth in loving and positive ways, there is no space for the spirit of suicide and alcohol abuse; it is shamed and it leaves.

Recommended next steps for communities and researchers seeking mutual engagement in health prevention and promotion activities involve: a) advancing IK in community health interventions to reduce disparities and promote well-being on AIAN groups; b) allowing IK to take lead in AIAN community health intervention research; c) focusing on community-level factors and cultural mechanisms in the development and evaluation of Indigenous interventions; d) developing measures and evaluation tools based in the IK; e) utilizing language, terms, symbols and theories from the culture and IK; f) identifying underlying functions of cultural mechanisms and process that may generalize across local contexts rather than rigid adherence to form as in strict components views of intervention ; and g) keeping in mind how ‘all communities have a qasgiq.’ In the end, we are all connected when we come into the circle and see the light of the world.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript describes work guiding a 20 year program of research funded by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities, and National Institute of General Medical Sciences R01AA11446, R21AA015541, R01AA023754, R21AA0016098, R24MD001626 and P20RR061430. We also thank all of the People Awakening and the Qungasvik Team, including our participants, community researchers, leadership council and project staff for their invaluable contributions to this collaborative team effort.

Footnotes

This section is heavily informed by the two Yup’ik community co-authors of this paper, B. Charles and S. John. Both co-authors are fluent Yup’ik speakers and are knowledge bearers in their respective communities. The Yup’ik Indigenous knowledge shared in this and other sections describing the Yup’ik Indigenous theories, models and processes are the unique and significant contributions of these co-authors.

Contributor Information

Stacy M. Rasmus, University of Alaska Fairbanks

Edison Trickett, University of Miami.

Billy Charles, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Simeon John, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

James Allen, University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth campus.

References

- Airhihenbuwa C, Ford C & Iwelunmor J (2014). Why culture matters in health current draft interventions: lessons from HIV/AIDS stigma and NCDs. Health Education and Behavior, 41(1), 78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium Epidemiology Center (2017). Alaska Native Health status report. Anchorage, AK: Alaska Native Tribal Helath Consortium Epidemiology Center. [Google Scholar]

- Allen J, Mohatt GV, Rasmus SM, Hazel K, Thomas L, Lindley S, & People Awakening Team (2006). The tools to understand: Community as co-researcher on culture specific protective factors for Alaska Natives. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community, 32(1/2), 41–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J , Levintoya M, Mohatt GV (2011). Suicide and alcohol related disorders in the U.S. Arctic: boosting research to address a primary determinant of circumpolar health disparities. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 70(5), 473–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J, Mohatt GV, Beehler S, & Rowe HL (2014). People Awakening: Collaborative research to develop cultural strategies for prevention in community intervention. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54(1–2), 100–111. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9647-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J, Mohatt GV, Fok CCT, Henry D, & Burkett RA & People Awakening Team. (2014). Protective factors model for alcohol abuse and suicide prevention among Alaska Native youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54(1–2), 125–139. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9661-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayunerak P, Alstrom D, Moses C, Charlie J, & Rasmus SM (2014). Yup’ik culture and context in Southwest Alaska: Community member perspectives of tradition, social change, and prevention. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54(1–2), 91–99. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9652-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Huang B, Fieland KC, Simoni JM, & Walters KL (2004) Culture, trauma, and wellness: A comparison of heterosexual and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and two-spirit Native Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 10(3), 287–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker B Goodman A & Debeck K (2017). Reclaiming Indigenous identifiies: culture as strength against suicide among Indigenous youth in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 108(2), e208–e210. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnhardt R, & Kawagley AO (2005). Indigenous knowledge systems and Alaska Native ways of knowing. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 36(1), 8–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bassett D, Tsosie U, & Nannauck S (2012). “Our Culture Is Medicine”: Perspectives of Native Healers on Posttrauma Recovery Among American Indian and Alaska Native Patients. The Permanente Journal, 16(1), 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battiste M (2005) Indigenous knowledge: Foundations for First Nations. Indigenous Nations Higher Education Consortium. [Google Scholar]

- Birman D, Trickett E, & Buchanan R (2005). A Tale of two cities: Replication of a study on the acculturation and adaptation of immigrant adolescents from the former Soviet Union in a different community context. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35(1–2), 87–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerregaard P (2001). Rapid socio-cultural change and health in the arctic. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 60(2), 102–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohensky EL, & Maru Y. 2011. Indigenous knowledge, science, and resilience: What have we learned from a decade of international literature on “integration”? Ecology and Society, 16(4), 6. [Google Scholar]

- Brady M (1995) Culture in treatment, culture as treatment: A critical appraisal of developments in addictions programs for Indigenous North Americans and Australians. Social Science & Medicine, 41, 1487–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brems C (1996). Substance use, mental health, and health in Alaska: Emphasis on Alaska Native People. Arctic Medical Research, 55, 135–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs J (2005). The use of Indigenous knowledge in development problems and challenges. Problems in Development Studies, 5(2), 99–114 [Google Scholar]

- Brown R, Dickerson D, & D’Amico E (2016). Cultural identity among urban American Indian/Alaska Native youth: implications for alcohol and drug use. Prevention Science, 17(7), 852–61. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0680-1. PMID:. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig J, & Hull-Jilly D (2012). Characteristics of suicide among Alaska Native and Alaska non-Native people 2003–2008 State of Alaska Epidemiological Bulletin. Department of Health and Social Services, Department of Behavioral Health, Anchorage, AK. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher J, Wendt D, Maracek J, & Goodman D (2014). Critical cultural awareness: Contributions to a globalizing psychology. American Psychologist, 69(7), 645–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan D, Thomas L Sigo R, Price L, Lonczak H, Lawrence N, … Bagley L (2015). Healing of the Canoe: Preliminary results of a culturally grounded intervention to prevent substance abuse and promote tribal identity for Native Youth in two Pacific Northwest tribes. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 22(1), 42–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durie M (2004). Understanding health and illness: research at the interface between science and Indigenous knowledge. International Journal of Epidemiology, 33(5), 1138–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fienup-Riordan A (1994). Boundaries and passages: Rule and ritual in Yup’ik Eskimo oral tradition. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feyerabend P (1975). Against method: Outline of an anarchistic theory of knowledge. NY: Verso Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP (2012). Indigenous traditional knowledge and substance abuse treatment outcomes: The problem of efficacy evaluation. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 38, 493–497. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.694528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP (2013). Redressing First Nations historical trauma: Theorizing mechanisms for Indigenous culture as mental health treatment. Transcultural Psychiatry, 50(5), 683–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP (2016). Alternative knowledges and the future of community psychology: provocations from an American Indian healing tradition. American Journal of Community Psychology, 58(3–4), 314–321. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP (2017). “It Felt Like Violence”: Indigenous knowledge traditions and the postcolonial ethics of academic inquiry and community engagement. American Journal of Community Psychology, 60, 353–360. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP, & Alcantara C (2007). Identifying effective mental health interventions for American Indians and Alaska Natives: A review of the literature. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13(4), 356–363. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP, & Calf Looking PE (2011). American Indian culture as substance abuse treatment: Pursuing evidence for a local intervention. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 43(4), 291–2961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez J, & Trickett EJ (2014). Collaborative measurement development as a tool in CBPR: measurement development and adaptation within the cultures of communities. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54(1–2), 112–124. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9655-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind J, LaNoue M, Lee C, Freeland L, & Freund R (2012). Feasibility, acceptability, and initial findings from a community-based cultural mental health intervention for American Indian youth and their families. Journal of Community Psychology, 40(4), 381–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall L Dell CA, Fornssler B, Hopkins C, Mushquash C, & Rowan M (2015). Research as cultural renewal: Applying Two-Eyed Seeing in a research project about cultural interventions in First Nations addictions treatment. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 69(2), 1–15. doi: 10.18584/iipj.2015.6.2.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasse C (2015). Culture as contested field An Anthropology of Learning. Springer Science+Business Media B.V; doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-9606-4_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henry D, Allen J, Fok CC, Rasmus S, Charles B, & People Awakening Team. (2012). Patterns of protective factors in an intervention for the prevention of suicide and alcohol abuse with Yup’ik Alaska Native youth. American Journal of Drug Alcohol Abuse, 38(5), 476–82. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.704460. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobe J, Adams A, Henderson J, Karanga N, Lee E, & Walyers K (2012). Community-responsive interventions to reduce cardiovascular risk in American Indians. Journal of Primary Prevention, 33, 153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumper-Reeves L, Dustman P, Harthun M, Kulis S, & Brown E (2014). American Indian cultures: How CBPR illuminated intertribal cultural elements fundamental to an adaptation effort, Prevention Science, 15(4), 547–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa-Singer M, Dressler W, George S, & Elwood W (2015). The cultural framework for health: An integrative approach for research and program design and evaluation. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Kirmeyer L (2012). Cultural competence and evidence-based practice in mental health: Epistemic communities and the politics of pluralism. Social Science and Medicine, 75, 249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmeyer L, Simpson C, & Cargo M (2003). Healing traditions: Culture, community, and mental health promotion with Canadian Aboriginal peoples. Australasian Psychiatry, 11, S15. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus R (1974). Suicidal behavior in north Alaskan Eskimo. Alaska Medicine, 16, 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus RF, & Buffler PA (1979). Sociocultural stress and the American Native in Alaska: An analysis of changing patterns of psychiatric illness and alcohol abuse among Alaskan natives. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 3(2), 111–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn TS (1996). The structure of scientific revolutions, 3rd. ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- LaFromboise T & Howard-Pitney B (1995). The Zuni Life Skills Development Curriculum: Description and evaluation of a suicide prevention program. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42(4), 479–486. [Google Scholar]

- Mohatt GV, Hazel KL, Allen J, Stachelrodt M, Hensel C, & Fath R (2004). Unheard Alaska: Culturally anchored participatory action research on sobriety with Alaska Natives. American Journal of Community Psychology, 33(3–4), 263–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohatt GV, Fok CCT, Henry D, People Awakening Team, & Allen J (2014). Feasibility of a community intervention for the prevention of suicide and alcohol abuse with Yup’ik Alaska Native youth: The Elluam Tungiinun and Yupiucimta Asvairtuumallerkaa studies. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54(1–2), 153–169. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9646-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohatt GV, Rasmus SM, Thomas L, Allen J, Hazel K, & Hensel C (2004). Tied together like a woven hat: Protective pathways to Alaska Native sobriety. Harm Reduction Journal, 1, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohatt GV, Rasmus SM/, Thomas L, Allen J, Hazel K, & Marlatt G,A (2008). Risk, resilience, and natural recovery: A model of recovery from alcohol abuse for Alaska Natives. Addiction, 103, 205–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed S, Walters K LaMarr J, Evans-Campbell T, & Freyberg S (2012). Finding middle ground: Negotiating university and tribal community interests in community-based participatory research. Nursing Inquiry 19(2), 116–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadasdy P (1999) The Politics of Tek: Power and the “integration” of knowledge. Arctic Anthropology, 36(1/2), 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto S, LeCroix C, Tann S, Rayle A, Kulis S, Dustman P, & Berceli D (2014). The implications of ecologically based assessment for primary prevention with Indigenous youth populations. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 27(2), 155–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popper K (2005). The logic of scientific discovery. New York: Routledge / Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmus SM (2014). Indigenizing CBPR: Evaluation of a community-based and participatory research process implementation of the Elluam Tungiinun (Towards Wellness) program in Alaska. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54(1–2), 170–179. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9653-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmus SM, Charles B, & Mohatt GV (2014). Creating Qungasvik (a Yup’ik intervention ‘‘toolbox’’): Case examples from a community-developed and culturally-driven intervention. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54(1–2), 140–152. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9651-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillitoe P (1998). The development of Indigenous knowledge: A new applied anthropology. Current Anthropology, 39(2), 223–252. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas L, Donovan D Sigo R Austin L, Marlatt GA, & Suquamish Tribe (2009). The community pulling together: A community-university partnership to reduce substance abuse and promote good health in a reservation tribal community. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 8, 283–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas L, Rosa C Forcehimes A, & Donovan D (2011). Research partnerships between academic institutions and American Indian and Alaska Native tribes and organizations: Effective strategies and lessons learned in a multi-site CTN study. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 37(5), 333–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett E, Trimble J, & Allen J (2014). Most of the story is missing: Advocating for a more complete intervention story. American Journal of Community Psychology. 54(1–2), 180–186. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9645-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinokurov A, Trickett E, & Birman D (2017). Context matters: Acculturation and underemployment of Russian-speaking refugees. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 57, 42–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler L & Gone J (2012). Culturally responsive suicide prevention in Indigenous communities: Unexamined assumptions and new possibilities. American Journal of Public Health, 102(5), 800–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]