Abstract

The standard placement of a subpalpebral lavage system may not be feasible in some horses with eyelid disease. We describe placement of a commercially available, indwelling nasolacrimal lavage system that circumvents eyelid perforation. This novel approach provided for effective delivery of drugs to 1 horse with periocular and corneal disease.

Résumé

Placement nasolacrymal normograde d’un système de lavage oculaire pour le traitement des maladies de l’oeil des équidés. Le placement standard d’un système de lavage subpalpébral peut ne pas être réalisable chez certains chevaux atteints de maladies oculaires. Nous décrivons le placement d’un système de lavage nasolacrymal à demeure qui évite la perforation de la paupière. Cette approche innovatrice a permis d’administrer des médicaments à un cheval atteint de maladie périoculaire et cornéenne.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

A wide range of equine ocular diseases require frequent administration of topical ophthalmic solutions. This administration can be challenging in eyes that are painful or have inflamed eyelids. The delivery of medication may be further complicated by periocular pathology, resulting from trauma or disease, or by fractious temperament.

Three techniques for placement of ocular-lavage systems have been described for remotely medicating the equine eye (1–3). The classic approach includes placement of a subpalpebral lavage (SPL) system through the dorsal eyelid with a smooth endplate that anchors into the dorsal conjunctival fornix (1). This system is highly effective and can be placed in the standing horse with routine sedation and local anesthesia. An inferior-eyelid placement has also been described in which the ophthalmic catheter is passed through the ventral eyelid near the medial canthus in a similar fashion (2). Limitations of these methods include puncturing the eyelid and the potential for corneal ulceration following tube displacement, or movement or misplacement of the footplate in the respective conjunctival fornix. Other ocular complications include eyelid swelling and local cellulitis or abscessation. Suture loss requiring re-suturing of the system, as well as loss or damage to specific pieces of the system, have been reported (1,2,4). A third approach involves partial retrograde cannulation of the nasolacrimal duct with a specially designed cannula (3). This system avoids puncturing the eyelids and has a reduced risk of corneal damage. Dislodgment of the system, however, may occur, and retrograde flushing of material into the eye from the proximal half of the nasolacrimal duct during routine use is unavoidable. Furthermore, the cannula is not widely available, and increased medication volume is required using this system relative to the SPL routes as significant wastage may occur within the duct.

In a subset of equine patients, especially those with periocular neoplasia or severely traumatized, burned, or scarred eyelids, penetration of the eyelid may be contraindicated. Furthermore, retrograde flushing of debris and potential pathogens may be inadvisable in horses with severe corneal disease. These patients require an alternative placement of the ocular-lavage system. This case report describes a novel placement of a commercially available ocular-lavage system via normograde cannulation of the nasolacrimal duct in a patient with periocular and corneal disease.

Case description

A 9-year-old, Draft-cross gelding, was presented to the Ontario Veterinary College — Health Sciences Centre (OVC-HSC) for evaluation and treatment of a suspected corneal ulcer. The horse had a 2-year history of recurring and extensive periocular sarcoids affecting the right eye and a series of both periocular injections of carboplatin and cisplatin bead placement that resulted in contraction and scarring of the eyelids with deformation of the palpebral margins (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Marked contraction and scarring of the eyelids with deformation of the palpebral margins.

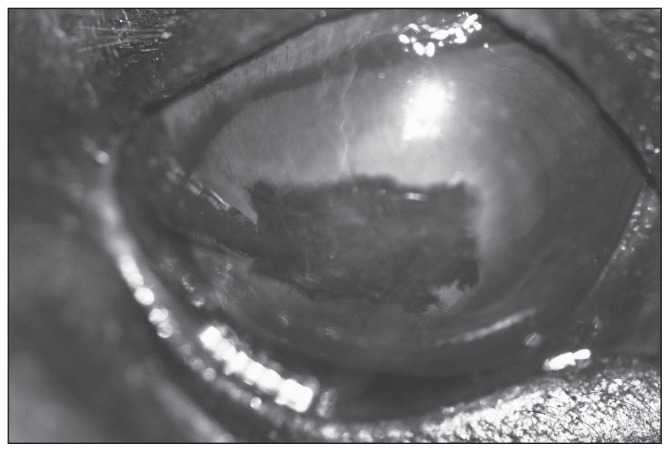

On ophthalmic examination, the horse was diagnosed with exposure keratitis resulting in a complex corneal ulcer (Figure 2). Both the right dorsal and ventral eyelids were markedly affected by scarring and deformation as a sequela to sarcoids and subsequent therapy. Due to the inability to fully close the palpebral fissure, tear distribution was impaired, and the corneal surface was left vulnerable and easily damaged. The horse’s blink reflex was accomplished by retraction of the globe and movement of the nictitating membrane. Cytology and fungal culture of the corneal ulcer revealed no fungal agents; cytology revealed diplococci bacteria and bacterial culture ultimately grew Streptococcus equi subspecies zooepidemicus susceptible to aminoglycosides and Branhamella ovis susceptible to cephalosporins.

Figure 2.

Exposure keratitis resulting in a complex corneal ulcer.

Due to the temperament of the horse and severity of the corneal disease, medicating the right eye frequently and remotely with an ocular-lavage system was recommended followed by placement of a conjunctival graft. The presence of dormant, although potentially active, sarcoids involving the entire periocular region precluded the placement of a standard ocularlavage system.

Prior to the placement of the ocular-lavage system, the patient was sedated with romifidine (Sedivet; Boehringer Ingelheim, Canada, Burlington, Ontario), 120 μg/kg body weight (BW), IV. Right-sided auriculopalpebral and frontal nerve blocks were performed with 2 mL of 2% lidocaine each (Alveda Pharmaceuticals, Toronto, Ontario) and the cornea was anesthetized with 2 mL of topical 0.5% proparacaine hydrochloride (Alcaine; Alcan, Mississauga, Ontario). The ventral lacrimal punctum was temporarily catheterized with a 3.5 Fr × 5.5 in tom-cat catheter (Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts, USA) and flushed normograde with sterile normal saline (Hospira, Montreal, Quebec) to ensure patency of the right nasolacrimal duct.

Preparation of the nasolacrimal lavage (NLL) system included linking 150 cm of 1 polypropylene suture (Ethicon; San Lorenzo, Puerto Rico, USA) to the SPL (MILA International, Florence, Kentucky, USA). Linking of the suture to the lavage tubing was done in a stepwise manner.

Step 1 — A 20 G needle was used to puncture the wall of the SPL tubing into the lumen approximately 2 cm from the system’s distal end with the needle directed out the end of the tubing (Figures 3A, B).

Step 2 — Approximately 10 cm of the suture was passed through the needle tip and out the hub, and the needle was removed leaving the suture through the wall of the tubing (Figures 3C, D).

Step 3 — The 20 G needle was then inserted into the lumen of the tubing’s distal end and punctured the wall, exiting 2 cm from the tubing’s distal end and directly opposite the first puncture (Figure 3E).

Step 4 — The short end of suture was then passed through the needle tip and out the hub; the needle was then removed, leaving the suture through the wall of the tubing and lying within the lumen (Figures 3F, G).

Step 5 — The short end of the suture was trimmed flush with the end of the tubing to leave the short end completely within the lumen of the SPL (Figure 3H).

Figure 3.

The needle was used to puncture the wall of the tubing into the lumen and was directed out the end (A–B). The suture was passed through the needle; the needle is removed (C–D). The needle was inserted into the lumen and used to puncture through the tubing opposite the first puncture (E). The suture was passed through the needle; the needle was removed (F–G). The short end of the suture was trimmed flush (H). The suture was threaded through AEC once hub was removed (I).

A 6 F arterial embolectomy catheter (#120806F; Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, California, USA) was lightly coated with sterile lubricant (Muko Lubricating Jelly; Cardinal Health Canada, Toronto, Ontario) in preparation for insertion into the ventral lacrimal punctum. Once inserted, a clockwise twist to the arterial embolectomy catheter (AEC) was needed to pass through the distal end of the nasolacrimal duct and exit the nasal punctum (Figure 4). The catheter’s stylet was then removed, and the AEC hub was cut and removed. The long end of the suture was then loaded into the AEC until it reached the blind, balloon end of the catheter adjacent to the nasal punctum, which was then cut to expose the suture within it. The suture was pulled taut to abut the distal end of the lavage system to the catheter (Figure 3I). The AEC was then advanced normograde with the lavage system in tow. Once the end of the SPL was exteriorized through the nasal punctum, ~3 cm of the hub end (loose end) of the system was cut to remove the linked suture and punctured tubing. The foot plate at the ventral lacrimal punctum was positioned between the palpebral conjunctiva and nictitating membrane and sitting atop the ventral lacrimal punctum (Figure 5). To secure the system, an incision was made in the false nostril and the system was threaded and secured to the skin of the lower bridge. The remaining tubing was affixed to the cheek piece of the horse’s halter on the contralateral side for easy access (Figure 6). The system’s hub end (loose end) was fitted with the injection port, and 0.5 mL doses of tobramycin (Sandoz Tobramycin, tobramycin ophthalmic solution; Sandoz, Boucherville, Quebec) and cefazolin (Cefazolin sodium; SteriMax, Oakville, Ontario) were administered every 4 h.

Figure 4.

The nasolacrimal duct is fully cannulated with the arterial embolectomy catheter (AEC).

Figure 5.

The ventral eyelid was retracted to expose the footplate at the ventral lacrimal punctum, which was positioned between the palpebral conjunctiva and nictitating membrane and sat atop the ventral lacrimal punctum.

Figure 6.

The tubing was threaded through the false nares and affixed to the cheek piece of the horse’s halter on the contralateral side.

Following placement of the NLL system, the horse was induced under general anesthesia and a dorsal conjunctival pedicle graft was created from tissue near the lateral canthus and placed over the ulcer following keratectomy. The placement of the graft was successful, and medical therapy initiated before surgery was continued to further treat the graft and underlying keratectomy. Upon recovery, several attempts were made with multiple types of equine visors over several days; ultimately, this patient was intolerant to any make of head gear available at the hospital.

Due to the large palpebral fissure and the reduced blink, organic material would accumulate on the eyelids as well as adhere to the corneal and conjunctival graft surfaces. Despite diligent care and frequent sterile saline corneal flushes, 10 d following placement of the graft, a small, focal abscess was detected within the graft tissue. Bacterial culture of the suspected abscess revealed Enterobacter cloacae susceptible to fluoroquinolones and drug therapy was adjusted to ofloxacin (Ocuflox, ofloxacin ophthalmic solution; Allergan, Irvine, California, USA). The conjunctival graft abscess healed without incident within 7 d.

Results

The NLL system was used successfully to treat severe corneal disease in the gelding with concurrent periocular sarcoid. The NLL system’s footplate was always visible on top of the ventral lacrimal punctum and did not appear to cause discomfort. No ocular complications were observed for the 50 d the system was in place. The NLL system was secure, functional, and required minimal maintenance at the level of the injection port. No increase in blink rate or facial discomfort was recognized during therapy. During drug administration and flushing of the system, the horse showed minimal adverse behavioral reactions similar to what would be expected with a standard SPL. The horse was sedated for removal of the NLL system. Following transection of the lavage tubing external to the nasal punctum, the system was easy to remove due to the accessibility of the footplate.

Due to the likelihood for corneal ulcer recurrence associated with the lack of properly functioning eyelids, the pedicle of the conjunctival graft was left intact to maintain blood supply. Frequent follow-up appointments for ongoing evaluation and treatment of new and recurring sarcoids allowed for over 2 y of monitoring. No complications associated with the nasolacrimal puncta, nasolacrimal duct, cornea, or conjunctival graft in either the short-term or long-term convalescent period were detected. Although with time the graft has become fully pigmented and vision is thus impaired, the horse has remained free of additional corneal pathology and has had no further ulceration since the graft was placed (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The conjunctival graft 1 year after placement. The graft has fully integrated into the cornea and is now fully pigmented.

Discussion

In clinical practice, a subset of equine patients will not be ideal candidates for the standard placement of an SPL (1,2) to treat corneal disease. Eyelid diseases including squamous cell carcinoma, sarcoid, eyelid laceration, eyelid burn, or severe blepharitis may render the dorsal and/or ventral eyelid and adjacent conjunctiva incompatible for placement. For these specific patients, an alternative, novel approach has been described herein using an ocular-lavage system widely utilized and readily available in ambulatory and private practice. Compared to the previously described placements of a standard SPL, our approach avoided penetration of an eyelid and allowed its use in a horse with periocular pathology. The footplate and space-occupying tubing acted as barriers to flow and avoided subsequent retrograde flushing of debris onto the corneal surface while no debris was observed within the tubing itself. Moreover, the footplate allowed for excellent security of the system. The NLL system was always functional and required minimal maintenance at the level of the injection port, similar to reports of traditional SPL systems (1,2,4). In retrospect, securing the system without incising the false nares would make this procedure fully non-invasive.

The use of the AEC was instrumental for the cannulation of the lavage system within the nasolacrimal duct. Due to its lack of rigidity, the lavage system could not be cannulated into the nasolacrimal duct alone. By linking the lavage system to a suture that then passed through the AEC, we were able to fully cannulate the nasolacrimal system with the lavage system. Although the linkage of the lavage system to the suture at first appeared intricate, it was reasonably simple to reproduce. Polypropylene suture was used due to its rigidity and memory, although another suture material may be used in its stead.

Limitations of this case report include the single patient so far treated with this method. As the typical placement of an SPL is rarely contraindicated, the use of the NLL system has not been deemed necessary in multiple cases so far. The potential for the footplate to cause corneal pathology in some horses, or the possibility that the nasolacrimal duct or puncta could be damaged by the placement or the presence of the tubing, was not evaluated in more than 1 patient. Furthermore, the presence of tubing at the nares could become irritating and problematic if traumatized with rubbing.

Further limitations of this placement include the requirement of a patent nasolacrimal duct, normal ventral lacrimal punctum, and the use of a specialized catheter. Although commercially available, not every equine practitioner will have an AEC on hand, and other potential catheters need to be investigated. Catheters to be considered must accommodate the dimensions of the nasolacrimal duct, which range in length from 24 cm (in a foal) to 29 to 33 cm (in adults) with luminal diameters ranging from 2 to 11 mm (5–7). Cannulation of the nasolacrimal duct in an adult horse using both a 1.2 mm and 1.7 mm × 56 cm urinary catheter (3.5 Fr–5 Fr Sovereign Polypropylene Catheter; Covidien Animal Health) has been reported (8). As with our case, a stylet or, alternatively, a wire (approximately 20 gauge) within the catheter may be needed for added rigidity to pass the selected catheter at the lower levels of the nasolacrimal duct due to the nasal cartilage anatomy (6,7).

In our patient, the described novel placement of an ocularlavage system resulted in an effective and secure method to administer ocular solutions. Although minor changes to the approach and substitution of listed instruments could be further evaluated, placement was straightforward with the described instruments. This approach should be considered in horses that are not ideal candidates for standard SPL systems. CVJ

Footnotes

Owner Informed Consent: As per standard protocol of case management at the OVC-HSC, owner consent to therapy including the placement of the nasolacrimal system was obtained.

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Dwyer AE. How to insert and manage a subpalpebral lavage system. Proc Annu Meet Am Assoc Equine Pract, Nashville, Tennessee. 2013;59:164–173. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giuliano EA, Maggs DJ, Moore CP, Boland LA, Champagne ES, Galle LE. Inferomedial placement of a single-entry subpalpebral lavage tube for treatment of equine eye disease. Vet Ophthalmol. 2000;3:153–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-5224.2000.00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brook D. Use of an indwelling nasolacrimal cannula for the administration of medication to the eye. Equine Vet J. 1983;15:135–137. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sweeney CR, Russell GE. Complications associated with use of a one hole subpalpebral lavage system in horses: 150 cases (1977–1996) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1997;211:1271–1274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nykamp SG, Scrivani PV, Pease AP. Computed tomography dacryocystography evaluation of the nasolacrimal apparatus. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2004;45:23–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2004.04004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Latimer CA, Wyman M, Diesem CD, Burt JK. Radiographic and gross anatomy of the nasolacrimal duct of the horse. Am J Vet Res. 1984;45:451–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spadari A, Spinella G, Grandis A, Romagnoli N, Pietra M. Endoscopic examination of the nasolacrimal duct in ten horses. Equine Vet J. 2011;43:159–162. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2010.00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoppini R, Tassan S, Barachetti L. Diode laser photoablation to correct distal nasolacrimal duct atresia in an adult horse. Vet Ophthalmol. 2014;17:174–178. doi: 10.1111/vop.12164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]