Abstract

The objectives of this study were to describe serial point-of-care test results in dogs infected with canine parvovirus (CPV), highlight clinicopathologic abnormalities at various timepoints, and investigate their association with the duration of hospitalization. Two-hundred and four dogs positive for CPV at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine between 2003 and 2015 were included. Data were recorded pertaining to emergency panel and venous blood gas tests at presentation, and every 12 hours thereafter (+/− 4 hours) for the first 72 hours of hospitalization. Common persistent abnormalities included hypoproteinemia, acidosis, hyponatremia, hypochloremia, hyperkalemia, and hyperbicarbonatemia. Ionized hypocalcemia was associated with a longer duration of hospitalization and mild hyperkalemia was associated with a shorter duration of hospitalization (P < 0.05). This study suggests that the use of point-of-care tests for in-hospital monitoring may provide insight into CPV case complexity and predict total hospitalization times.

Résumé

Association entre les résultats des tests au point de service et la durée de l’hospitalisation pour l’infection par le parvovirus canin (2003–2015). Les objectifs de cette étude consistaient à décrire les résultats des tests au point de service chez les chiens infectés par le parvovirus canin (CPV), à souligner les anomalies clinico-pathologiques à divers moments et à étudier leur association avec la durée d’hospitalisation. Deux cent quatre chiens positifs pour le CPV au Western College of Veterinary Medicine entre 2003 et 2015 ont été inclus. Des données ont été consignées en lien avec le panel d’urgence et les tests de gaz du sang veineux à la présentation et toutes les 12 heures par la suite (+/− 4 heures) pour les 72 premières heures d’hospitalisation. Les anomalies persistantes communes incluaient l’hypoprotéinémie, l’acidose, l’hyponatrémie, l’hypochlorémie, l’hyperkaliémie et l’hyperbicarbonatémie. L’hypocalcémie inonisée était associée à une plus longue durée d’hospitalisation et une légère hyperkaliémie était associée à une plus courte durée d’hospitalisation (P < 0,05). Cette étude suggère que l’usage des tests au point de service pour la surveillance à l’hôpital peut fournir de l’information à propos de la complexité des cas de CPV et prédire la durée totale d’hospitalisation.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

Introduction

Canine parvovirus (CPV) is a common worldwide pathogen resulting in the non-specific presentation of acute vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia, and lethargy (1,2). The virus primarily targets young unvaccinated puppies, but unvaccinated dogs of all ages are susceptible to the potentially life-threatening disease (1,3). As supportive therapy is the mainstay of treatment protocols (1,2,4,5), in-hospital monitoring has remained a focus of clinical research (5,6).

Point-of-care (POC) tests have been used extensively in human and veterinary emergency and critical care settings to monitor disease progression and changes in patient status (7–9). While POC tests such as packed cell volume, total protein, and venous blood gas have been used to monitor differences between prospective treatment groups in CPV (10), few studies have described the common clinicopathologic abnormalities observed during the hospitalization period and their clinical usefulness in relation to disease progression (11). Furthermore, the association between these serial patient-side diagnostics and the duration of hospitalization of dogs infected with CPV has yet to be investigated.

This study aims to describe serial POC test results over the first 3 d in hospital, highlight common clinicopathologic abnormalities, and investigate an association between these abnormalities and the duration of hospitalization in dogs surviving treatment of CPV.

Materials and methods

Medical records from the Western College of Veterinary Medicine Veterinary Medical Centre (WCVM-VMC) at the University of Saskatchewan were searched for all cases of canine parvovirus (CPV) infection from 2003 to 2015. Dogs were included in the study if a positive test result on a SNAP Canine Parvovirus Antigen Test (IDEXX Laboratories Canada, Markham, Ontario) was obtained; owners opted to pursue medical treatment; the dog was hospitalized at the WCVM-VMC; and the dog survived to discharge from the hospital. Dogs were excluded from the study if they were treated as an outpatient; discharged against medical advice; transferred to another veterinary clinic for continued supportive therapy; re-hospitalized within 72 h following discharge; or the hospitalization records were unavailable. Non-survivors were excluded from the study due to insufficient numbers for statistical conclusions to be made.

Data were recorded from the medical records pertaining to patient-side emergency panel (EP) test results consisting of a packed cell volume (PCV), blood glucose (BG), total protein (TP) and Azostix (Azostix Reagent Strips; Siemens Canada, Oakville, Ontario) blood urea nitrogen (BUN), in addition to venous blood gas (VBG) results consisting of pH, bicarbonate, sodium, potassium, chloride, ionized calcium, glucose, and lactate. Test results were recorded when available at presentation followed by every 12 h (+/− 4 h) for the first 72 h of hospitalization. A single blood gas machine was used from 2003 to 2015, and data from 34 healthy adult dogs were used to define an arterial blood gas reference interval for the analyzer. Age-related reference intervals from Harper et al (12) were used for the EP variables of PCV and TP for dogs ≤ 8 wk, 8.1 to 16 wk, 16.1 wk to 1 y, and > 1 y of age. Reference intervals from Prairie Diagnostic Services (PDS) were used for the EP BG variable. Azostix (Siemens Canada) BUN test results were recorded as categorical variables consisting of 1.79 to 5.36 mmol/L, 5.36 to 9.28 mmol/L, 10.71 to 14.28 mmol/L, and 17.85 to 28.57 mmol/L. Azotemia on the EP was defined as an Azostix BUN reading ≥ 10.71 mmol/L (13). Patient-side BG readings that were too low to obtain a reading were assigned a value of 1.0 mmol/L.

Statistical analysis was done using a commercial software package (Stata Statistical Software: Release 15; StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess normality of continuous variables. The median, minimum, and maximum were reported for all non-parametric variables; the median was also used for all parametric to nonparametric variable comparisons. Proportions were described using the count and percentage. The 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated for all proportions using the binomial exact method. Associations between clinicopathologic findings and the duration of hospitalization (non-parametric) were assessed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Comparisons were not assessed for groups consisting of less than 5 dogs. For all comparisons, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Two-hundred and four dogs met the criteria of the study. The median age and weight of dogs at the time of diagnosis was 19 wk (range: 2 wk to 9 y) and 8.3 kg (range: 0.5 to 51.4 kg), respectively. Twenty dogs (10%, 95% CI: 6% to 15%) were ≤ 8 wk, 65 dogs (32%, 95% CI: 26% to 39%) were 8.1 to 16 wk, 100 dogs (49%, 95% CI: 42% to 56%) were 16 wk to 1 y, and 19 dogs (9%, 95% CI: 6% to 14%) were > 1 y of age. One-hundred and five dogs (51%, 95% CI: 44% to 59%) were intact males, 87 dogs (43%, 95% CI: 36% to 50%) were intact females, 9 dogs (4%, 95% CI: 2% to 8%) were castrated males, and 3 dogs (1%, 95% CI: 0% to 4%) were spayed females. Ninety-nine dogs (49%, CI: 41% to 56%) were classified as mixed breeds and 105 dogs (51%, 95% CI: 44% to 59%) were classified as purebreds. Notable breeds included 17 (8%, 95% CI: 5% to 13%) German shepherd crosses; 10 (5%, 95% CI: 2% to 9%) Labrador retriever crosses; 10 (5%, 95% CI: 2% to 9%) Siberian husky crosses; 8 (4%, 95% CI: 2% to 8%) border collie crosses; and 8 (4%, 95% CI: 2% to 8%) Rottweiler crosses.

All dogs received intravenous fluid therapy throughout hospitalization.

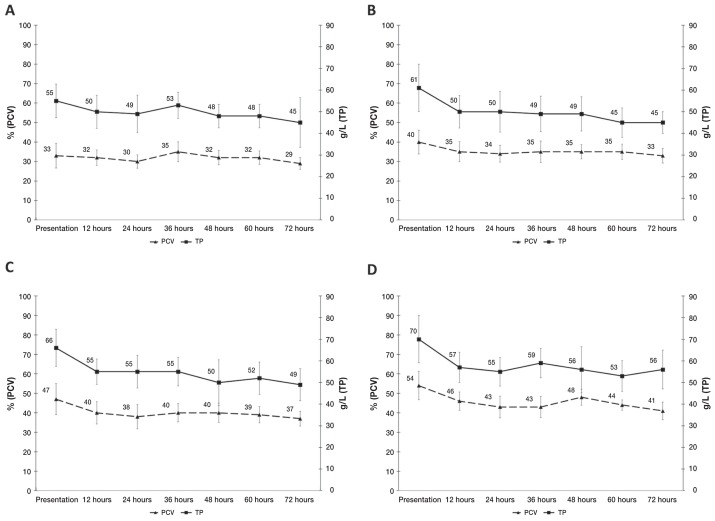

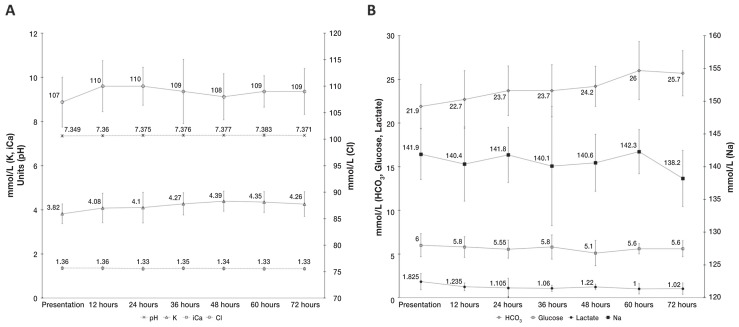

The numbers of dogs with point-of-care test results available throughout the first 3 d of hospitalization are shown in Table 1. The median BUN was 1.79 to 5.36 mmol/L at all timepoints. Median PCV and TP results over the first 72 h of hospitalization are summarized in Figure 1. Median VBG results over the first 72 h of hospitalization are summarized in Figure 2. Common persistent abnormalities identified on EP and VBG results include hypoproteinemia, acidosis, hyponatremia, hypochloremia, hyperkalemia, and hyperbicarbonatemia. The proportion of dogs with these abnormalities at presentation, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 h post-admission are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Number of dogs by 12-hour intervals that survived canine parvovirus infection with available point-of-care test results for the first 3 days in hospital.

| Variable | Presentation | 12 h | 24 h | 36 h | 48 h | 60 h | 72 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Packed cell volume (EP) | 170 | 96 | 80 | 99 | 51 | 74 | 42 |

| Blood glucose (EP) | 159 | 91 | 73 | 90 | 47 | 70 | 39 |

| Total protein (EP) | 170 | 96 | 80 | 98 | 51 | 74 | 42 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (EP) | 159 | 84 | 60 | 80 | 41 | 63 | 31 |

| pH | 129 | 38 | 33 | 29 | 17 | 17 | 11 |

| HCO3− | 125 | 37 | 33 | 28 | 17 | 17 | 11 |

| Na | 130 | 38 | 33 | 29 | 17 | 17 | 11 |

| K | 130 | 37 | 33 | 29 | 17 | 17 | 11 |

| Cl | 129 | 38 | 33 | 28 | 17 | 17 | 11 |

| iCa | 129 | 38 | 32 | 29 | 17 | 17 | 11 |

| Glucose | 125 | 37 | 32 | 29 | 17 | 17 | 11 |

| Lactate | 126 | 36 | 30 | 26 | 17 | 17 | 11 |

EP — emergency panel.

Figure 1.

Serial median PCV (packed cell volume) and TP (total protein) over the first 3 days of hospitalization in dogs that survived canine parvovirus infection, categorized by age. A — ≤ 8 wk [PCV reference interval (RI): 20% to 41%, TP RI: 14 to 50 g/L]; B — 8.1 to 16 wk (PCV RI: 20% to 69%, TP RI: 16 to 35 g/L); C — 16.1 wk to 1 y (PCV RI: 32% to 54%, TP RI: 19 to 57 g/L); D — > 1 y (PCV RI: 38% to 56%, TP RI: 22 to 50 g/L). Time categories on the x-axis include data +/− 4 h from the respective timepoint. Reference intervals established by Harper et al (12). Error bars display +/− 1 standard deviation.

Figure 2.

Serial median venous blood gas results over the first 3 days of hospitalization in dogs that survived canine parvovirus infection. Time categories on the x-axis include data +/− 4 h from the respective timepoint. A — pH [reference interval (RI): 7.395 to 7.4812, K (potassium, RI: 3.4 to 4.3 mmol/L), iCa (ionized calcium, RI: 1.31 to 1.40 mmol/L), Cl (chloride, RI: 113 to 121 mmol/L)]. B — HCO3 (bicarbonate, RI: 17.3 to 24.8 mmol/L), glucose (RI: 4.8 to 6.6 mmol/L), lactate (RI: 0.45 to 2.33 mmol/L), and Na (sodium, RI: 143.1 to 149.2 mmol/L). Reference intervals established at Prairie Diagnostic Services from arterial samples of 34 healthy adult dogs. Error bars display +/− 1 standard deviation.

Table 2.

Proportion of dogs that survived canine parvovirus infection displaying common clinicopathologic abnormalities on point-of-care tests throughout the first 3 days in hospital.

| Variable | 0 h % (n, N) | 95% CI | 12 h % (n, N) | 95% CI | 24 h % (n, N) | 95% CI | 36 h % (n, N) | 95% CI | 48 h % (n, N) | 95% CI | 60 h % (n, N) | 95% CI | 72 h % (n, N) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoproteinemiaa | 4 (7, 170) | 2 to 8 | 13 (12, 96) | 7 to 21 | 25 (20, 80) | 16 to 36 | 17 (17, 98) | 10 to 26 | 31 (16, 51) | 19 to 46 | 24 (18, 74) | 15 to 36 | 36 (15, 42) | 22 to 52 |

| Acidosis (pH < 7.395) | 88 (114, 129) | 82 to 93 | 79 (30, 38) | 63 to 90 | 70 (23, 33) | 51 to 84 | 69 (20, 29) | 49 to 85 | 76 (13, 17) | 50 to 93 | 65 (11, 17) | 38 to 86 | 91 (10, 11) | 59 to 100 |

| Hyponatremia (Na < 143.1 mmol/L) | 85 (111, 130) | 78 to 91 | 82 (31, 38) | 66 to 92 | 85 (28, 33) | 68 to 95 | 90 (26, 29) | 73 to 98 | 88 (15, 17) | 64 to 99 | 82 (14, 17) | 57 to 96 | 91 (10, 11) | 59 to 100 |

| Hypochloremia (Cl < 113 mmo/L) | 97 (125, 129) | 92 to 99 | 79 (30, 38) | 63 to 90 | 82 (27, 33) | 65 to 93 | 75 (21, 28) | 55 to 89 | 76 (13, 17) | 50 to 93 | 88 (15, 17) | 64 to 99 | 82 (9, 11) | 48 to 100 |

| Hyperkalemia (K > 4.3 mmol/L) | 17 (22, 130) | 11 to 24 | 32 (12, 37) | 18 to 50 | 39 (13, 33) | 23 to 58 | 48 (14, 29) | 29 to 67 | 59 (10, 17) | 33 to 82 | 59 (10, 17) | 33 to 82 | 45 (5, 11) | 17 to 77 |

| Hyperbicarbonatemia (HCO3− > 24.8 mmol/L) | 10 (13, 125) | 6 to 17 | 22 (8, 37) | 10 to 38 | 24 (8, 33) | 11 to 42 | 36 (10, 28) | 19 to 56 | 41 (7, 17) | 18 to 67 | 59 (10, 17) | 33 to 82 | 55 (6, 11) | 23 to 83 |

Total protein < 14 g/L; ≤ 8 wk; < 16 g/L, 8.1 to 16 wk; < 19 g/L, 16.1 wk to 1 y; < 22 g/L, > 1 y.

n — number of affected dogs; N — total population; 95% CI — confidence interval; Age-related reference interval for TP established by Harper et al (12); remaining reference intervals established at Prairie Diagnostic Services from arterial samples of 34 healthy adult dogs.

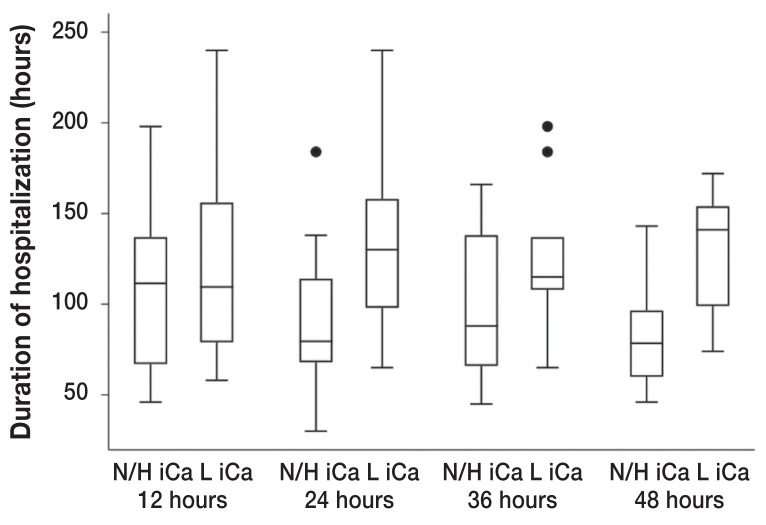

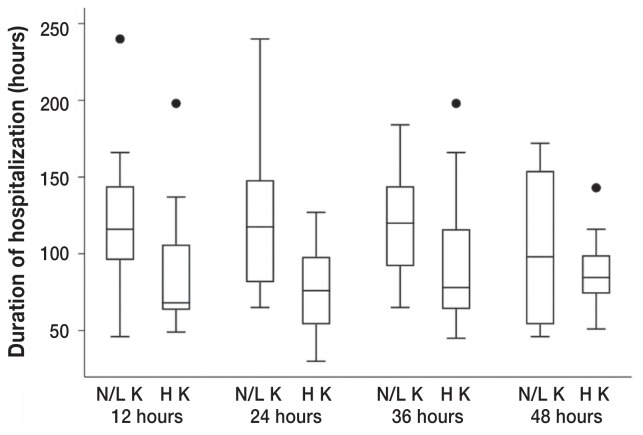

A decreased ionized calcium and an increased potassium were significantly associated with the duration of hospitalization at various timepoints. Dogs with ionized hypocalcemia at both 24 h (P = 0.018) and 48 h (P = 0.035) had a significantly longer median duration of hospitalization (130 h and 141 h, respectively) compared to dogs without this clinicopathologic abnormality (79.5 h and 78.5 h, respectively) (Figure 3). The significance of ionized calcium concentrations was further supported by the finding that dogs presenting with mild ionized hypercalcemia (range: 1.41 to 1.54 mmol/L) had a significantly shorter median duration of hospitalization of 68 h compared to 94.5 h for dogs presenting with either normal or decreased ionized calcium concentrations (P = 0.044). Dogs with mild hyperkalemia at 12 (range: 4.38 to 6.8 mmol/L; P = 0.047), 24 (range: 4.33 to 6.15 mmol/L; P = 0.005), and 36 (range: 4.31 to 5.06 mmol/L; P = 0.047) hours had a significantly shorter median duration of hospitalization (68, 76, and 78 h, respectively) compared with dogs that had either normal or decreased potassium concentrations (116, 117.5, and 120 h, respectively) (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Box plot of the duration of hospitalization of dogs that survived canine parvovirus infection that had a low ionized calcium (L iCa) at 12 (P = 0.551), 24 (P = 0.018), 36 (P = 0.195), and 48 h (P = 0.035) (+/− 4 h) into hospitalization compared with dogs that did not have this abnormality (N/H iCa, normal or high ionized calcium) on venous blood gas. The box plot displays the first quartile, median, and third quartile durations of hospitalization. Whiskers display the minimum and maximum durations of hospitalization that do not exceed 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR), represented by the vertical axis of the box plot. Points plotted beyond the maximum whisker value represent single durations of hospitalization that exceeded 1.5 times the IQR.

Figure 4.

Box plot of the duration of hospitalization of dogs that survived canine parvovirus infection that had a high potassium (H K) at 12 (P = 0.034), 24 (P = 0.005), 36 (P = 0.047), and 48 h (P = 0.696) (+/− 4 h) into hospitalization compared to dogs that did not have this abnormality (N/H K, normal or high potassium) on venous blood gas. The box plot displays the first quartile, median, and third quartile durations of hospitalization. Whiskers display the minimum and maximum durations of hospitalization that do not exceed 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR), represented by the vertical axis of the box plot. Points plotted beyond the maximum whisker value represent single durations of hospitalization that exceeded 1.5 times the IQR.

No significant association was found between the duration of hospitalization and PCV, TP, glucose, pH, bicarbonate, chloride, or lactate abnormalities at any time, nor was there a significant association with the presence of azotemia on the EP.

Discussion

Historically, most prognostic investigations pertaining to CPV have focused on the clinical profile of dogs at admission to the veterinary hospital. Previous studies have reported on VBG findings at presentation of CPV cases (14,15) and a strong ion model at presentation has been developed to highlight acid-base disturbances (16). However, more recent research has focused on evaluation of prognostic indicators at various timepoints following presentation (17–21). Multiple studies have reported significant differences between survivors and non-survivors at 24 h into the hospitalization period (17–19,21); consequently, this has been suggested as the optimal time for prognostication (6). The prognostic value of POC test results throughout hospitalization has yet to be evaluated, despite a previous study reporting VBG findings at 24 h into hospitalization (11).

In this study, most of the canine parvovirus patients were less than 1 y old (1). Multiple studies have demonstrated significantly lower PCV (12,22–24) and TP (12,22,23) values in dogs less than 1 y of age; consequently, age-specific reference intervals were used for the analysis of these variables. Additional age-related changes were found pertaining to the variables measured on blood gas analysis in our study. A previous study demonstrated that puppies < 12 wk of age had lower sodium and chloride concentrations in addition to higher potassium and ionized calcium concentrations compared to adult dogs at all measured timepoints (24). Unfortunately, the adult reference intervals established on the analyzer used in that study (24) differed significantly from the adult reference intervals established for the analyzer used for all samples in the current study. As a result, age-specific reference intervals reported in the previous study were not applied to the samples in our study, and age-specific reference intervals for the blood gas machine used throughout the duration of our study were not available. The authors caution that the use of adult reference intervals for variables obtained on the blood gas analyzer may have introduced statistical error in the present study. Furthermore, the identification of hyponatremia, hypochloremia, and hyperkalemia as common abnormalities throughout hospitalization in the present study may be a reflection of age rather than true abnormalities.

The only significant finding at presentation herein was the association between mild hypercalcemia and a shorter duration of hospitalization (P = 0.044). Due to the mild nature of the elevations in ionized calcium (range: 1.41 to 1.54 mmol/L), it is likely that this isolated finding is a reflection of prolonged hospitalization times in dogs with ionized hypocalcemia identified at 24 h (P = 0.018) and 48 h (P = 0.035). Although hypercalcemia is a common finding in young growing dogs (24) the authors believe that the mild elevation in ionized calcium at presentation was most likely due to dehydration. Ionized calcium measured after fluid deficit correction may therefore be a more appropriate indicator of case complexity and prognosis as observed in this study. Ionized hypocalcemia was associated with a prolonged duration of hospitalization at 24 and 48 h. In this study, the lack of significant POC predictors at presentation for hospitalization time supports the importance of evaluating clinicopathologic prognostic indicators past admission.

Ionized hypocalcemia has been identified as an important electrolyte disturbance in critically ill dogs (25) and the presence of ionized hypocalcemia has previously been associated with prolonged hospitalization times in dogs presenting for trauma (26). Proposed mechanisms for its development include aggressive fluid therapy, acquired or relative hypoparathyroidism, hypomagnesemia, and vitamin D resistance or deficiency (25). Additionally, sepsis and protein-losing enteropathies have been associated with the clinicopathologic abnormality (25). For many patients there is not a clear underlying pathogenesis (25). Due to the complexity of its development, the identification of ionized hypocalcemia and subsequent prolonged hospitalization times in cases of CPV is likely multifactorial. The lack of age-specific reference intervals for ionized calcium in the current study may have dampened the association found between ionized hypocalcemia and longer hospitalization times. As dogs < 1 y of age have higher ionized calcium levels than adults (24), the significance of lower ionized calcium levels found in this study is unlikely to represent a type I error.

The association found between mild hyperkalemia at 12, 24, and 36 h and a shorter duration of hospitalization in this study may be a reflection of underlying pathophysiological case complexity. Although serum potassium concentrations have been found to be higher in puppies relative to adult reference intervals (24), CPV infection has numerous effects on the relationship between potassium excretion and potassium ingestion which largely determines potassium homeostasis (27). As most dogs presenting with CPV are clinically dehydrated or hypovolemic, reduced renal excretion of potassium secondary to a reduction in effective plasma volume likely contributed to the elevated potassium concentrations (27). Furthermore, many dogs in the study were acidotic over the first 3 d of hospitalization, which likely contributed to the elevations in potassium concentrations measured on POC tests (27).

For less severe cases, this underlying pathophysiology is clinically apparent. In cases of severe CPV infection, the combination of anorexia and increased gastrointestinal losses may be contributing a greater degree to potassium homeostasis resulting in normal or low potassium concentrations in the face of dehydration, hypovolemia, and acidosis (27). The mild hyperkalemia identified at 12, 24, and 36 h in this study may be explained clinically by a shorter time to the resolution of anorexia, vomiting, and diarrhea, thus resulting in a shorter duration of hospitalization. Loss of this significant association past 36 h of hospitalization is thought to be attributed to rehydration.

As potassium concentrations have been shown to be higher in puppies compared to adults (24), this may have influenced the significant association found in our study between mild hyperkalemia and a shorter duration of hospitalization. It is possible that a type I error exists with respect to the effect of mild hyperkalemia on duration of hospitalization in this study. However, as young age has previously been deemed a negative prognostic indicator in CPV infection (6,19), the authors suspect that the mild hyperkalemia was a true reflection of decreased disease severity as opposed to younger dogs having shorter hospitalization times.

This study was limited to the outcome of duration of hospitalization rather than survival due to a limited number of non-survivors that had POC test results available at the various timepoints. Low power to detect an association between clinicopathologic abnormalities and hospitalization times remain a significant limitation of the study at various timepoints due to a low number of dogs with certain abnormalities and consequent unreliability of statistical analysis. Further limitations of the study revolve around its retrospective nature. As the acquisition of POC diagnostics was not standardized to every 12 h, a range of +/− 4 h was used for each timepoint to increase power in exchange for a decrease in accuracy in the measurement of time. Emergency panel data did not take into account whether patients received a plasma transfusion at any point throughout the first 3 d of hospitalization; therefore, TP concentrations may have been confounded by treatment interventions.

The use of POC tests for in-hospital monitoring can provide insight into CPV case complexity and aid in prognostication. Statistical models allowing for the integration of individual changes over time with respect to baseline values are suggested for future studies in addition to prospective investigations to increase the accuracy of time variables. CVJ

Footnotes

Supported in part by the Western College of Veterinary Medicine’s Interprovincial Undergraduate Student Summer Research Program.

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Goddard A, Leisewitz AL. Canine parvovirus. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2010;40:1041–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prittie J. Canine parvoviral enteritis: A review of diagnosis, management, and prevention. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2004;14:167–176. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalli Iris, Leontides LS, Mylonakis ME, Adamama-Moraitou K, Rallis T, Koutinas AF. Factors affecting the occurrence, duration of hospitalization and final outcome in canine parvovirus infection. Res Vet Sci. 2010;89:174–178. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pollock RV, Coyne MJ. Canine parvovirus. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1993;23:555–568. doi: 10.1016/S0195-5616(93)50305-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mylonakis M, Kalli I, Rallis T. Canine parvoviral enteritis: An update on the clinical diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Vet Med Res Reports. 2016;7:91–100. doi: 10.2147/VMRR.S80971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schoeman JP, Goddard A, Leisewitz AL. Biomarkers in canine parvovirus enteritis. N Z Vet J. 2013;61:217–222. doi: 10.1080/00480169.2013.776451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flatland B, Freeman KP, Vap LM, Harr KE ASVCP. ASVCP guidelines: Quality assurance for point-of-care testing in veterinary medicine. Vet Clin Pathol. 2013;42:405–423. doi: 10.1111/vcp.12099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castro H, Oropello J, Halpern N. Point-of-care testing in the intensive care unit. The intensive care physician’s perspective. Am J Clin Path. 1995;104(4 Suppl 1):S95–S9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richey M, McGrath C, Portillo E, Scott M, Claypool L. Effect of sample handling on venous PCO2, pH, bicarbonate, and base excess measured with a point-of-care analyzer. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2004;14:253–258. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venn EC, Preisner K, Boscan PL, Twedt DC, Sullivan LA. Evaluation of an outpatient protocol in the treatment of canine parvoviral enteritis. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2017;27:52–65. doi: 10.1111/vec.12561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nappert G, Dunphy E, Ruben D, Mann FA. Determination of serum organic acids in puppies with naturally acquired parvoviral enteritis. Can J Vet Res. 2002;66:15–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harper EJ, Hackett RM, Wilkinson J, Heaton PR. Age-related variations in hematologic and plasma biochemical test results in Beagles and Labrador Retrievers. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2003;223:1436–1442. doi: 10.2460/javma.2003.223.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berent AC, Murakami T, Scroggin RD, Borjesson DL. Reliability of using reagent test strips to estimate blood urea nitrogen concentration in dogs and cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;227:1253–1256. doi: 10.2460/javma.2005.227.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heald R, Jones B, Schmidt D. Blood gas and electrolyte concentrations in canine parvoviral enteritis. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1986;22:745–748. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rai A, Nauriyal D. Note on acid-base and blood gas dynamics in canine parvoviral enteritis. Indian J Vet Med. 1992;12:87–88. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burchell RK, Schoeman JP, Leisewitz AL. The central role of chloride in the metabolic acid-base changes in canine parvoviral enteritis. Vet J. 2014;200:152–156. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goddard A, Leisewitz AL, Christopher MM, Duncan NM, Becker PJ. Prognostic usefulness of blood leukocyte changes in canine parvoviral enteritis. J Vet Intern Med. 2008;22:309–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2008.0073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schoeman JP, Goddard A, Herrtage ME. Serum cortisol and thyroxine concentrations as predictors of death in critically ill puppies with parvoviral diarrhea. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2007;231:1534–1539. doi: 10.2460/javma.231.10.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoeman JP, Herrtage ME. Serum thyrotropin, thyroxine and free thyroxine concentrations as predictors of mortality in critically ill puppies with parvovirus infection: A model for human paediatric critical illness? Microbes Infect. 2008;10:203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dossin O, Rupassara SI, Weng HY, Williams DA, Garlick PJ, Schoeman JP. Effect of parvoviral enteritis on plasma citrulline concentration in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2011;25:215–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2010.0671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McClure V, van Schoor M, Thompson PN, Kjelgaard-Hansen M, Goddard A. Evaluation of the use of serum C-reactive protein concentration to predict outcome in puppies infected with canine parvovirus. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2013;243:361–366. doi: 10.2460/javma.243.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brenten T, Morris PJ, Salt C, Raila J, Kohn B, Schweigert FJ, Zentek J. Age-associated and breed-associated variations in haematological and biochemical variables in young labrador retriever and miniature schnauzer dogs. Vet Rec Open. 2016;3(1):e000166. doi: 10.1136/vetreco-2015-000166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosset E, Rannou B, Casseleux G, Chalvet-Monfray K, Buff S. Age-related changes in biochemical and hematologic variables in Borzoi and Beagle puppies from birth to 8 weeks. Vet Clin Pathol. 2012;41:272–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-165X.2012.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Brien MA, McMichael MA, Le Boedec K, Lees G. Reference intervals and age-related changes for venous biochemical, hematological, electrolytic, and blood gas variables using a point of care analyzer in 68 puppies. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2014;24:291–301. doi: 10.1111/vec.12162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holowaychuk MK. Hypocalcemia of critical illness in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2013;43:1299–317. vi–vii. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holowaychuk MK, Monteith G. Ionized hypocalcemia as a prognostic indicator in dogs following trauma. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2011;21:521–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-4431.2011.00675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phillips SL, Polzin DJ. Clinical disorders of potassium homeostasis. Hyperkalemia and hypokalemia. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1998;28:545–564. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(98)50055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]