Abstract

The average age of the US population continues to increase. Age is the most important determinant of disease and disability in humans, but the fundamental mechanisms of aging remain largely unknown. Many age-related diseases are associated with an impaired fibrinolytic system. Elevated plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) levels are reported in age-associated clinical conditions including cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, obesity and inflammation. PAI-1 levels are also elevated in animal models of aging. While the association of PAI-1 with physiological aging is well documented, it is only recently that its critical role in the regulation of aging and senescence has become evident. PAI-1 is synthesized and secreted in senescent cells and contributes directly to the development of senescence by acting downstream of p53 and upstream of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3. Pharmacologic inhibition or genetic deficiency of PAI-1 was shown to be protective against senescence and the aging-like phenotypes in kl/kl and Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester-treated wild-type mice. Further investigation into PAI-1’s role in senescence and aging will likely contribute to the prevention and treatment of aging-related pathologies.

Keywords: PAI-1, senescence, aging

Advanced age contributes to the development of frailty and disease in humans, but the fundamental mechanisms that drive the physiological aging are incompletely understood.1,2 As the elderly population of the United States and other Western countries continues to grow, the need to investigate and understand these mechanisms has never been greater. While aging is inevitable, therapeutic interventions that target aging-related pathways could delay or even prevent the onset of chronic conditions that lead to aging and thus increase the overall healthspan of the population.

A substantial body of evidence indicates that many age-related diseases are associated with an impaired fibrinolytic system. The main enzyme of fibrinolysis, plasmin, is generated from the inactive precursor plasminogen by the serine proteases tissue type and urokinase-type plasminogen activators (t-PA and uPA, respectively). Plasmin degrades fibrin clots in the vasculature and can remodel the extracellular matrix directly and through the activation of matrix metalloproteinases.3,4 Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) is the primary physiological inhibitor of both t-PA and uPA and therefore is the main regulator of plasminogen activation system. Over the years, studies have shown that PAI-1’s influence is not limited to its canonical function in fibrinolysis, but also includes other diverse biological processes such as cell adhesion and migration, cell-matrix interactions, signaling pathways, replicative senescence, proteolysis, and physiological aging.

Fibrinolytic activity is known to decrease with age,5–7 in part due to increase in PAI-1 activity.8 While age-dependent increases in plasma PAI-1 levels are well documented, it is recently that this protein is being viewed as a critical determinant of aging. In this review, we will discuss how PAI-1 is associated with physiological aging and examine the molecular mechanisms of how PAI-1 is mediates its effects on aging-related pathologies (►Table 1).

Table 1.

Physiological manifestations of aging influenced by PAI-1

| • Emphysema |

| • Arterial thrombosis |

| • Hair loss |

| • Amyloid deposition |

| • Arteriosclerosis/hypertension |

| • Calcification |

| • Infertility |

Elevated PAI-1 Levels Are Associated with Age-Related Conditions

Increased PAI-1 activity levels lead to reduced plasmin generation and as a result, promote both a prothrombotic and profibrotic environment, both of which are clinical conditions related to aging. Elevated levels of PAI-1 are associated with veno-occlusive disease, ischemia, arterial thrombosis, and venous thrombosis.9–11 PAI-1 is also predictive of both initial12 and recurrent13 myocardial infarction. An excess of PAI-1 results in collagen accumulation and the development of fibrotic disorders. PAI-1 levels are also increased in patients with aortic valve stenosis, the most common vascular disease affecting the elderly population. PAI-1 expression in the valves is proportional to the rate of valve calcification.14

Plasma PAI-1 levels significantly increase in several clinical conditions that arise because of aging, including obesity,15 type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM),16 and inflammation.17 In humans, PAI-1 is independently correlated with many markers of adiposity, including body mass index (BMI), visceral fat mass, serum triglyceride levels, and liver steatosis.18–20 PAI-1 predicts the development of T2DM independent of other known risk factors, including age, sex, ethnicity, BMI, smoking, family history of diabetes, and insulin sensitivity.21,22 In addition to the age-depended increases of PAI-1 in plasma, PAI-1 accumulates in atherosclerotic plaques,23–26 a finding that is exaggerated inT2DM.27 Interestingly, Pandolfi et al have found that PAI-1 expression is markedly augmented in the vessel walls of patients with T2DM even before the development of atherosclerotic plaques, strongly suggesting that local PAI-1 gene expression is an important factor for increased cardiovascular risk in diabetes.28 The PAI-1 promoter contains response elements for several proinflammatory cytokines. Factors such as interleukin-1, transforming growth factor-ß (TGF-ß), lipopolysaccharide,17 tumor necrosis factor-α,29 and endotoxin30 can upregulate PAI-1 expression during inflammation. PAI-1 can also promote neutrophil recruitment by regulating cell migration.31

Similar to humans, animal studies have demonstrated an age-associated elevation in the plasma levels and activity of PAI-1.32 PAI-1 accumulates in murine heart33 and porcine aortic valves34 as a function of age. Moreover, restraint stress- induced PAI-1 expression is dramatically enhanced in aged animals.32,35,36

PAI-1 Is Elevated in Animal Models of Aging

Increased levels of PAI-1 expression have been observed in mouse models of “accelerated aging,” including Klotho (kl/kl) and BubR1H/H mice. kl/kl mice stop growing at the age of 3 weeks with an average lifespan of 56 days, and develop pathologies that resemble human aging including emphysema, arteriosclerosis, and skin atrophy.37 kl/kl mice have an age- dependent increase in plasma PAI-1 levels as well as increased expression of PAI-1 mRNA and protein accumulation in the kidney, aorta, and heart.38 Similarly, BubR1H/H mice develop various aging-like phenotypes that include a shortened lifespan, sarcopenia, cataracts, arterial stiffening, reduced stress tolerance, and impaired wound healing.39 Interestingly, the most dramatic increase in PAI-1 expression is observed in the tissues most affected by aging in BubR1H/H mice: adipose tissue, smooth muscle, and eyes.40

PAI-1 Is a Critical Determinant of the Age- Related Abnormalities

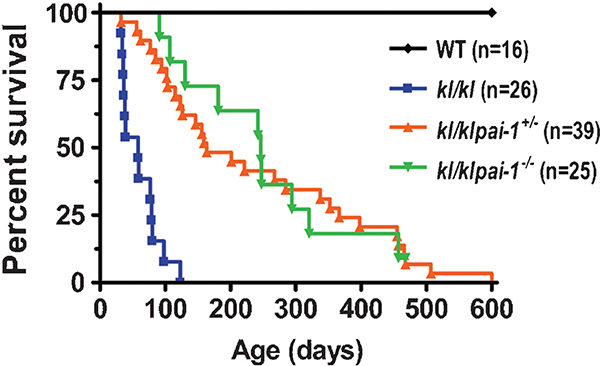

It is not immediately clear whether the increase in PAI-1 levels with aging represents a biomarker of aging, or if PAI-1 actually regulates organismal aging. Recent work from our group provides the first demonstration that modulation of PAI-1 levels can actually prolong survival and prevent the development of age-related diseases in a mouse model of accelerated aging. To investigate the role of PAI-1 in the aginglike pathology, we modulated PAI-1 levels in the established murine model of accelerated aging, kl/kl mice. Both partial and complete PAI-1 deficiency had a pronounced effect on the longevity of kl/kl mice. The median survival of kl/kl mice increased 2.8-fold by partial deletion of PAI-1, and 4.2-fold in PAI-1 -deficient kl/kl mice (►Fig. 1). This improvement in survival was also associated with evidence of increased overall vigor and health, as kl/klpai-1−/− mice exhibited near normal weight gain over time and spontaneous physical activity. In addition, a PAI-1 deficiency restored the fertility of kl/kl mice and preserved organ structure. Thus, partial or complete loss of PAI-1 expression prevented age-dependent enlargement of air spaces and associated alveolar destruction, and protected against age-induced ectopic calcification in kidney and heart tissues without altering serum levels of phosphate, calcium, alkaline phosphatase, and aldosterone.

Fig. 1.

Effect of PAI-1 deficiency on lifespan of Klotho mice. Log-rank analysis shows that the survival curves for WT, kl/kl, kl/klpai-1+/− and kl/klpai-1−/− mice differ significantly (p < 0.0001). PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; WT, wild-type.

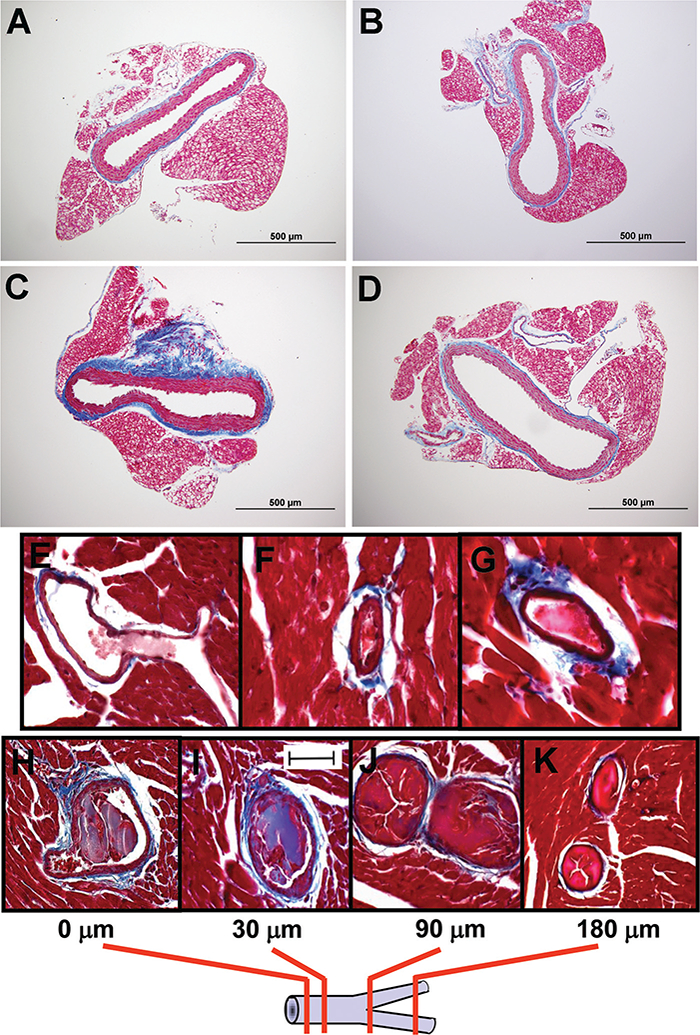

Likewise, modulation in PAI-1 levels can influence the development of hypertension and arteriosclerosis. Hypertension is one of the most prevalent age-related conditions (80% of people older than 65 years have measurable high blood pressure.).41 Both genetic deficiency and pharmacological inhibition of PAI-1 attenuated the increases in systolic blood pressure and aortic arteriosclerosis that develop in mice treated with long-term nitric oxide synthases inhibition42–44 (►Fig. 2A-D).

Fig. 2.

A novel plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1) TM5441 attenuates Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME)-induced periaortic fibrosis. Photomicrograph of Masson trichome-stained aortic cross-sections illustrate the extent of fibrosis in (A) untreated wild-type (WT) mice, (B) WT mice treated with TM5441, (C) WT mice that received L-NAME, and (D) WT mice coadministered with L-NAME and TM5441. Transgenic mice overexpressing human PAI-1 developed perivascular fibrosis and coronary arterial thrombosis. Panels (E) through (F) show thrombi detected in three different mice. Panels (H) through (K) display serial heart sections to detect the extent of coronary thrombi. The schematic below the photomicrographs illustrates sections at 0 (starting point), 30, 90, and 180 μm to follow the thrombus in this large-sized coronary artery that bifurcates at the 90 μm-section into two branches that are also thrombosed.

The critical role of PAI-1 in the regulation of organismal aging is also suggested from previous work from our laboratory indicating that transgenic overexpression of a functionally stable form of PAI-1 is sufficient to induce multiple age-dependent phenotypic abnormalities that resemble age-related pathology, including alopecia, systemic amyloidosis,45 and perivascular fibrosis and coronary arterial thrombosis46 (►Fig. 2E-K).

Effects of PAI-1 on Molecular Mechanisms of Aging

PAI-1 Promotes Cellular Senescence

Although aging is associated with increased susceptibility to all major chronic diseases, the fundamental mechanisms that give rise to age-related diseases remain largely unknown. Since the discovery of senescence in cultured cells, cellular senescence has been suggested to be linked to aging-related diseases. Accumulation of senescent cells has been detected in various aged tissues and organs47 as well as in atherosclerotic plaques of coronary arteries obtained from patients with ischemic heart disease.48 Furthermore there is a direct correlation between replicative potential of cells in culture and lifespan potential of the species from which they are derived. Thus, cells derived from progeroid patients exhibited accelerated cellular senescence in vitro.49 In addition to the earlier observations, a recent study provided evidence that senescent cells are directly contributing to age-related dysfunction. Baker et al observed that removal of senescent cells can prevent or delay tissue dysfunction in BubR1H/H progeroid mice.37

PAI-1 expression has been reported to increase during replicative senescence in various cell types50–55 and is a validated senescence indicator. Together with proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors secreted by senescent cells, PAI-1 is a part of the senescence phenotype (►Table 2), termed the senescence-messaging secretome (SMS). It is not immediately clear whether SMS proteins represent biomarkers of replicative senescence, or if these proteins actually regulate organismal aging by signaling to other cells.

Table 2.

Senescence factors affected by PAI-1

| • IGFBP3 |

| • p16Ink4a |

| • Telomere length |

| • IL-6 |

| • TGF-ß |

| • Gap junctions |

Abbreviations: IGFBP3, insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3; IL-6, interleukin 6; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-ß;

Until recently, PAI-1 has been regarded as a marker that merely correlates with, rather than contributes to, senescence.56,57 However, recent works suggested that PAI-1 is not merely a senescence marker, but both necessary and sufficient for the induction of replicative senescence in vitro.58,59 Not only is PAI-1 capable of inducing replicative senescence in mouse embryonic fibroblasts59 and MCF-7 breast cancer cells,60 but PAI-1-deficient fibroblasts and endothelial cells can also escape growth arrest and senescence. Conversely, overexpression of PAI-1 in proliferating keratinocytes induces growth arrest.61 Importantly, results published by Kortlever et al indicate that PAI-1 is a critical downstream target of the tumor-suppressor p53 in the induction of replicative senescence in vitro.59 In addition, a positive association between PAI-1 and p53 also has been reported in vivo.62,63 Analysis of PAI-1 in healthy subjects suggests that p53 polymorphism plays a crucial role in determining PAI-1 levels in aging.64

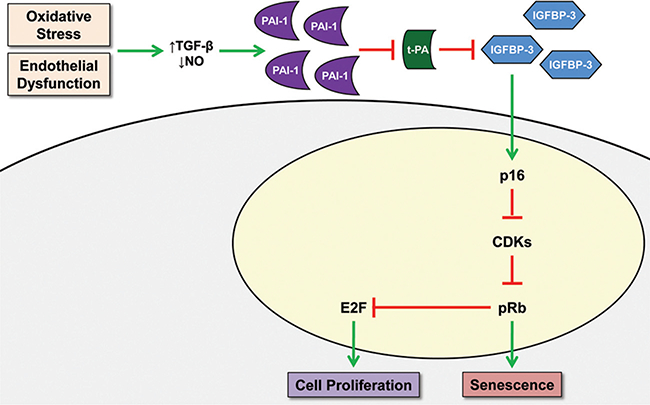

Recently, Elzi et al identified a downstream target of PAI-1, which provides a potential mechanism to explain the role of PAI-1 in promoting cellular senescence in vitro.60 The expression of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (IGFBP3) is increased in response to senescent stimuli (UV, hypoxia, etoposide, and H2O2) and in doxorubicin-induced senescence. PAI-1 secreted by nascent senescent cells inhibits the t-PA-dependent proteolysis of IGFBP3 (►Table 2). As PAI- 1 is the main physiological inhibitor of t-PA, IGFBP3 is thought to be a critical downstream target of PAI-1-induced senescence. Simply stated, PAI-1 promotes senescence by limiting the metabolism of IGFBP3 (►Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Proposed schematic model illustrating role of extracellular PAI-1 in regulating senescence. CDKs, cyclin dependent kinases; IGFBP3, insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3; PAI-1, a plasminogen activator inhibitor; TGF-𝛃, transforming growth factor-𝛃; t-PA, tissue plasminogen activator

Data from our group provided the first demonstration that modulation of the SMS can actually prevent the development of senescence in a mouse model of accelerated aging. PAI-1-deficient had a profound impact on senescence in kl/kl mice. We observed that both partial and complete PAI-1 deficiency lowered levels of the SMS factors IGFBP3 and interleukin-6 in plasma of kl/kl mice to levels seen in wild-type (WT) mice (►Table 2). PAI-1 deficiency also provided partial protection of telomere integrity in numerous tissues and prevented the nuclear accumulation of the senescence marker p16Ink4a in kl/kl mice65 (►Table 2). Inhibition of PAI-1 activity also protected against the development of senescence in another aging-related model. Pharmacological inhibition of PAI-1 prevented telomere shortening and reduced p16Ink4a expression in aortas of mice with Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME)-induced senescence42 (►Table 2).

PAI-1 Mediates Senescence by Affecting the Dynamics of Intercellular Communication

Nelson et al recently reported that senescent cells induced a DNA damage response in neighboring cells through gap junction-mediated cell-cell communication and secretion of reactive oxygen species. Continuous exposure to senescent cells induced senescence in replication-competent fibroblasts nearby.66 This mechanism may actually be PAI-1 dependent, as Heberlein et al have two recent publications indicating that PAI-1 plays a critical role in gap junction formation and that myoepithelial junction formation is reduced in PAI-1-deficient mice fed a high fat diet.67,68 The findings that gap junction formation and signaling may be enhanced or impaired via PAI-1 regulation of the PA system open new perspectives that PAI-1 mediates senescence by affecting the dynamics of intercellular communication.

Conclusions

While aging is the major risk factor that is related to the development of chronic and acute diseases in humans, the fundamental molecular mechanisms driving physiological and pathophysiological aging need to be investigated further. However, numerous studies have implicated PAI-1 in the aging process. Circulating and tissue levels of PAI-1 increase with age and impair the biological processes such as fibrinolysis, cell migration, senescence, and aging. Age-dependent elevations in PAI-1 levels have been associated with the clinical conditions observed with advanced aging including cardiovascular diseases (thrombosis, atherosclerosis, and arteriosclerosis), organ fibrosis, inflammation, obesity, and diabetes. Senescent cells accumulate in aged tissues and cellular senescence is thought to contribute to aging. PAI-1 was shown to be a critical determinant of replicative senescence and contributes to senescence in vivo by impairing the proteolytic clearance of the SMS factor IGFBP3. Furthermore, we have recently shown that pharmacological inhibition or genetic deficiency of PAI-1 was protective against senescence and aging-like phenotypes in kl/kl mice as well as arteriosclerosis and senescence in L-NAME-treated WT mice. These preliminary data suggest that inhibition of PAI-1 activity offers a therapeutic approach to prevent or reduce tissue senescence and organismal aging, which in turn would extend the healthspan of populations.

Footnotes

Issue Theme Age-Related Changes in Thrombosis and Hemostasis; Guest Editors: Hau C. Kwaan, MD, FRCP, Brandon J. McMahon, MD, and Elaine M. Hylek, MD, MPH.

References

- 1.Rodier F, Campisi J. Four faces of cellular senescence. J Cell Biol 2011;192(4):547–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campisi J, d’Adda di Fagagna F. Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007;8(9): 729–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lijnen HR. Plasmin and matrix metalloproteinases in vascular remodeling. Thromb Haemost 2001;86(1):324–333 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lijnen HR, Van Hoef B, Lupu F, Moons L, Carmeliet P, Collen D. Function of the plasminogen/plasmin and matrix metalloproteinase systems after vascular injury in mice with targeted inactivation of fibrinolytic system genes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1998;18(7):1035–1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abbate R, Prisco D, Rostagno C, Boddi M, Gensini GF. Age-related changes in the hemostatic system. Int J Clin Lab Res 1993;23(1): 1–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gleerup G, Winther K. The effect of ageing on platelet function and fibrinolytic activity. Angiology 1995;46(8):715–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meade TW, Chakrabarti R, Haines AP, North WR, Stirling Y. Characteristics affecting fibrinolytic activity and plasma fibrinogen concentrations. BMJ 1979;1(6157):153–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aillaud MF, Pignol F, Alessi MC, et al. Increase in plasma concentration of plasminogen activator inhibitor, fibrinogen, von Wille-brand factor, factor VIII:C and in erythrocyte sedimentation rate with age. Thromb Haemost 1986;55(3):330–332 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aznar J, Estelles A. Role of plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 in the pathogenesis of coronary artery diseases. Haemostasis 1994; 24(4):243–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith LH, Dixon JD, Stringham JR, et al. Pivotal role of PAI-1 in a murine model of hepatic vein thrombosis. Blood 2006;107(1): 132–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meltzer ME, Lisman T, de Groot PG, et al. Venous thrombosis risk associated with plasma hypofibrinolysis is explained by elevated plasma levels of TAFI and PAI-1. Blood 2010;116(1):113–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thogersen AM, Jansson JH, Boman K, et al. High plasminogen activator inhibitor and tissue plasminogen activator levels in plasma precede a first acute myocardial infarction in both men and women: evidence for the fibrinolytic system as an independent primary risk factor. Circulation 1998;98(21): 2241–2247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamsten A, de Faire U, Walldius G, et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor in plasma: risk factor for recurrent myocardial infarction. Lancet 1987;2(8549):3–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kochtebane N, Alzahrani AM, Bartegi A. Expression of uPA, tPA, and PAI-1 in Calcified Aortic Valves. Biochem Res Int 2014; 2014:658643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juhan-Vague I, Alessi MC. PAI-1, obesity, insulin resistance and risk of cardiovascular events. Thromb Haemost 1997;78(1 ):656–660 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alessi MC, Juhan-Vague I. PAI-1 and the metabolic syndrome: links, causes, and consequences. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2006; 26(10):2200–2207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sawdey M, Podor TJ, Loskutoff DJ. Regulation of type 1 plasminogen activator inhibitor gene expression in cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells. Induction by transforming growth factor-beta, lipopolysaccharide, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Biol Chem 1989;264(18):10396–10401 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Estellés A, Dalmau J, Falco C, et al. Plasma PAI-1 levels in obese children—effect of weight loss and influence of PAI-1 promoter 4G/ 5G genotype. Thromb Haemost 2001;86(2):647–652 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindeman JH, Pijl H, Toet K, et al. Human visceral adipose tissue and the plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1. IntJ Obes (Lond) 2007; 31(11):1671–1679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbato A, Iacone R, Tarantino G, et al. ; Olivetti Heart Study Research Group. Relationships of PAI-1 levels to central obesity and liver steatosis in a sample of adult male population in southern Italy. Intern Emerg Med 2009;4(4):315–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Festa A, D’Agostino R Jr, Tracy RP, Haffner SM ; Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Elevated levels of acute-phase proteins and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 predict the development of type 2 diabetes: the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study. Diabetes 2002;51(4):1131–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanaya AM, Wassel Fyr C, Vittinghoff E, et al. Adipocytokines and incident diabetes mellitus in older adults: the independent effect of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166(3):350–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneiderman J, Sawdey MS, Keeton MR, et al. Increased type 1 plasminogen activator inhibitor gene expression in atherosclerotic human arteries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992;89(15):6998–7002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raghunath PN, Tomaszewski JE, Brady ST, Caron RJ, Okada SS, Barnathan ES. Plasminogen activator system in human coronary atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1995;15(9): 1432–1443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lupu F, Heim DA, Bachmann F, Hurni M, Kakkar VV, Kruithof EK. Plasminogen activator expression in human atherosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1995;15(9):1444–1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robbie LA, Booth NA, Brown AJ, Bennett B. Inhibitors of fibrinolysis are elevated in atherosclerotic plaque. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1996;16(4):539–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sobel BE, Woodcock-Mitchell J, Schneider DJ, Holt RE, Marutsuka K, Gold H. Increased plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 in coronary artery atherectomy specimens from type 2 diabetic compared with nondiabetic patients: a potential factor predisposing to thrombosis and its persistence. Circulation 1998;97(22): 2213–2221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pandolfi A, Cetrullo D, Polishuck R, et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 is increased in the arterial wall of type II diabetic subjects. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001;21(8):1378–1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hou B, Eren M, Painter CA, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha activates the human plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene through a distal nuclear factor kappaB site. J Biol Chem 2004; 279(18):18127–18136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quax PH, van den Hoogen CM, Verheijen JH, et al. Endotoxin induction of plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 mRNA in rat tissues in vivo. J Biol Chem 1990; 265(26):15560–15563 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arndt PG, Young SK, Worthen GS. Regulation of lipopolysaccha-ride-induced lung inflammation by plasminogen activator Inhibitor-1 through a JNK-mediated pathway. J Immunol 2005;175(6): 4049–4059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamamoto K, Shimokawa T, Yi H, et al. Aging accelerates endotoxin-induced thrombosis: increased responses of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and lipopolysaccharide signaling with aging. Am J Pathol 2002;161(5):1805–1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sobel BE, Lee YH, Pratley RE, Schneider DJ. Increased plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 (PAI-1 ) in the heart as a function of age. Life Sci 2006;79(17):1600–1605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balaoing LR, Post AD, Liu H, Minn KT, Grande-Allen KJ. Age-related changes in aortic valve hemostatic protein regulation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014;34(1):72–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamamoto K, Takeshita K, Shimokawa T, et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 is a major stress-regulated gene: implications for stress-induced thrombosis in aged individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99(2):890–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emeis JJ, Van den Hoogen CM. Pharmacological modulation of the endotoxin-induced increase in plasminogen activator inhibitor activity in rats. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 1992;3(5): 575–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, et al. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature 1997; 390(6655):45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takeshita K, Yamamoto K, Ito M, et al. Increased expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 with fibrin deposition in a murine model of aging, “Klotho” mouse. Semin Thromb Hemost 2002;28(6):545–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baker DJ, Perez-Terzic C, Jin F, et al. Opposing roles for p16Ink4a and p19Arf in senescence and ageing caused by BubR1 insufficiency. Nat Cell Biol 2008;10(7):825–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baker DJ, Wijshake T, Tchkonia T, et al. Clearance of p16Ink4a- positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature 2011;479(7372):232–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burt VL, Cutler JA, Higgins M, et al. Trends in the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the adult US population. Data from the health examination surveys, 1960 to 1991. Hypertension 1995;26(1):60–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boe AE, Eren M, Murphy SB, et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor- 1 antagonist TM5441 attenuates Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester-induced hypertension and vascular senescence. Circulation 2013;128(21 ):2318–2324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaikita K, Fogo AB, Ma L, Schoenhard JA, Brown NJ, Vaughan DE. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 deficiency prevents hypertension and vascular fibrosis in response to long-term nitric oxide synthase inhibition. Circulation 2001;104(7):839–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaikita K, Schoenhard JA, Painter CA, et al. Potential roles of plasminogen activator system in coronary vascular remodeling induced by long-term nitric oxide synthase inhibition. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2002;34(6):617–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eren M, Gleaves LA, Atkinson JB, King LE, Declerck PJ, Vaughan DE. Reactive site-dependent phenotypic alterations in plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 transgenic mice. J Thromb Haemost 2007; 5(7):1500–1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eren M, Painter CA, Atkinson JB, Declerck PJ, Vaughan DE. Age- dependent spontaneous coronary arterial thrombosis in transgenic mice that express a stable form of human plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. Circulation 2002;106(4):491–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Campisi J Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell 2005;120(4):513–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Minamino T, Miyauchi H, Yoshida T, Ishida Y, Yoshida H, Komuro I. Endothelial cell senescence in human atherosclerosis: role of telomere in endothelial dysfunction. Circulation 2002;105(13): 1541–1544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen JH, Hales CN, Ozanne SE. DNA damage, cellular senescence and organismal ageing: causal or correlative? Nucleic Acids Res 2007;35(22):7417–7428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cardus A, Uryga AK, Walters G, Erusalimsky JD. SIRT6 protects human endothelial cells from DNA damage, telomere dysfunction, and senescence. Cardiovasc Res 2013;97(3):571–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Comi P, Chiaramonte R, Maier JA. Senescence-dependent regulation of type 1 plasminogen activator inhibitor in human vascular endothelial cells. Exp Cell Res 1995;219(1):304–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martens JW, Sieuwerts AM, Bolt-deVries J, et al. Aging of stromal-derived human breast fibroblasts might contribute to breast cancer progression. Thromb Haemost 2003;89(2): 393–404 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mu XC, Higgins PJ. Differential growth state-dependent regulation of plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 expression in senescent IMR-90 human diploid fibroblasts. J Cell Physiol 1995;165(3): 647–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D, Lowe SW. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell 1997;88(5):593–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.West MD, Shay JW, Wright WE, Linskens MH. Altered expression of plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor during cellular senescence. Exp Gerontol 1996;31(1–2):175–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Collado M, Serrano M. The power and the promise of oncogene- induced senescence markers. Nat Rev Cancer 2006;6(6): 472–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goldstein S, Moerman EJ, Fujii S, Sobel BE. Overexpression of plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 in senescent fibroblasts from normal subjects and those with Werner syndrome. J Cell Physiol 1994;161(3):571–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kortlever RM, Bernards R. Senescence, wound healing and cancer: the PAI-1 connection. Cell Cycle 2006;5(23):2697–2703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kortlever RM, Higgins PJ, Bernards R. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 is a critical downstream target of p53 in the induction of replicative senescence. Nat Cell Biol 2006;8(8): 877–884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Elzi DJ, Lai Y, Song M, Hakala K, Weintraub ST, Shiio Y. Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1—insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 cascade regulates stress-induced senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109(30):12052–12057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kortlever RM, Brummelkamp TR, van Meeteren LA, Moolenaar WH, Bernards R. Suppression of the p53-dependent replicative senescence response by lysophosphatidic acid signaling. Mol Cancer Res 2008;6(9):1452–1460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lara PC, Lloret M, Valenciano A, et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor- 1 (PAI-1 ) expression in relation to hypoxia and oncoproteins in clinical cervical tumors. Strahlenther Onkol 2012;188(12):1139–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Offersen BV, Alsner J, Ege Olsen K, et al. A comparison among HER2, TP53, PAI-1, angiogenesis, and proliferation activity as prognostic variables in tumours from 408 patients diagnosed with early breast cancer. Acta Oncol 2008;47(4):618–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Testa R, Bonfigli AR, Salvioli S, et al. The Pro/Pro genotype of the p53 codon 72 polymorphism modulates PAI-1 plasma levels in ageing. Mech Ageing Dev 2009;130(8):497–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eren M, Boe AE, Murphy SB, et al. PAI-1-regulated extracellular proteolysis governs senescence and survival in Klotho mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111(19):7090–7095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nelson G, Wordsworth J, Wang C, et al. A senescent cell bystander effect: senescence-induced senescence. Aging Cell 2012;11(2): 345–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Heberlein KR, Han J, Straub AC, et al. A novel mRNA binding protein complex promotes localized plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 accumulation at the myoendothelial junction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2012;32(5):1271–1279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Heberlein KR, Straub AC, Best AK, et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 regulates myoendothelial junction formation. Circ Res 2010;106(6):1092–1102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]