Abstract

Early endosomes are organelles that receive macromolecules and solutes from the extracellular environment. The major function of early endosomes is to sort these cargos into recycling and degradative compartments of the cell. Degradation of the cargo involves maturation of early endosomes into late endosomes, which, after acquisition of hydrolytic enzymes, form lysosomes. Endosome maturation involves recruitment of specific proteins and lipids to the early endosomal membrane, which drives changes in endosome morphology. Defects in early endosome maturation are generally accompanied by alterations in morphology, such as increase in volume and/or number. Enlarged early endosomes have been observed in Alzheimer’s disease and Niemann Pick Disease type C, which also exhibit defects in endocytic sorting. This article discusses the mechanisms that regulate early endosome morphology and highlights the potential importance of endosome maturation in the retinal pigment epithelium.

Keywords: Early endosome, Enlarged endosome, Endosome morphology, Endosome maturation, Age-related macular degeneration

1. Introduction

Animal cells transfer various macromolecules (nutrients, receptors, ligands) and solutes from the surrounding medium to the interior of the cell by endocytosis. These macromolecules and solutes are then transported to various compartments in the cell by a system of endocytic vesicles (Mellman 1996; Jovic et al. 2010). These vesicles, especially the early endosomes that are the first endocytic vesicles to receive this cargo, play important roles in the proper functioning of the cell (Gruenberg et al. 1989). Early endosomes are responsible for nutrient uptake, degradation of metabolic by-products, transport of materials to specific compartments in the cell, and regulating the cell-surface expression of receptors and transporters. Defects in early endosomes have been implicated in neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and Niemann Pick Disease type C (Nixon 2005; Maxfield 2014).

Early endosomes have specific proteins and lipids on their membranes that confer organelle identity and regulate association with other effector proteins (Huotari and Helenius 2011; Jovic et al. 2010). Defective association of proteins with early endosomes interferes with endosome maturation and early endosome function. In this review, we focus on mechanisms that regulate endosome maturation, which in turn impact the morphology of early endosomes.

2. Early Endosomes: Morphology and Maturation

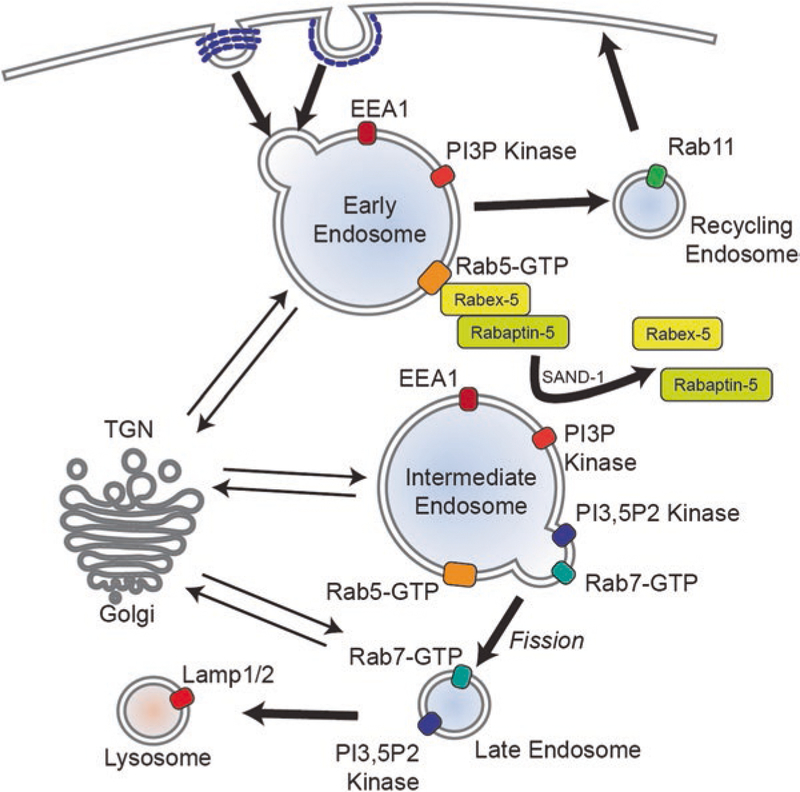

Early endosomes are very heterogeneous in terms of morphology and have a high capacity for homotypic and heterotypic fusion (Gruenberg et al. 1989). During endocytosis, primary vesicles carrying cargo bud off from the plasma membrane and fuse with early endosomes to deliver their contents (Mellman 1996; Jovic et al. 2010) (see Fig. 1). Early endosomes continue to receive cargo by fusion, which leads to an increase in size (Dunn et al. 1989; Maxfield and McGraw 2004). As a result, these endosomes can display a network of tubular, cisternal, and tubulovesicular morphologies (Gruenberg et al. 1989). A major role of early endosomes is to sort various proteins into recycling and degradative compartments (Huotari and Helenius 2011). Plasma membrane proteins, lipids, and ligands, such as transferrin, are recycled back to the cell membrane by the fission of smaller, recycling endosomes from the early sorting endosomes (Dunn et al. 1989; Ciechanover et al. 1983). The proteins marked for degradation, such as the EGF receptor, are sorted to cisternal parts of early endosomes, which mature into late endosomes. These late endosomes either mature into lysosomes or fuse with pre-existing lysosomes to degrade the cargo (Carpenter and Cohen 1979, Dunn and Maxfield 1992). During maturation of early endosomes to late, some proteins also get shuttled to the trans-Golgi network via the retromer complex (Progida and Bakke 2016). On the other hand, early endosomes undergoing maturation receive membrane proteins and hydrolytic enzymes by fusion of secretory vesicles from the trans-Golgi network, which is essential for the maturation process.

Fig. 1.

Primary vesicles carrying endocytosed cargo fuse with the early endosome, which is marked by EEA1, PI3P kinase, and Rab5-GTP. Some cargo is recycled back to the plasma membrane by the recycling endosomes. On the early endosomes, Rabex-5 and Rabaptin-5 binding maintains Rab5 in its GTP state. SAND-1/Mon1 can dissociate Rabex-5 and Rabaptin-5 from the endosome membrane and allow association with Rab7. Early endosomes also undergo bidirectional transport with the trans-Golgi network. Rab7 is added onto domains of the endosome as Rab5 is removed. Endocytic carrier vesicles bud off from the endosomal membrane and mature into late endosomes. Alternatively, early endosomes may gradually mature into late endosomes also. Ultimately, late endosomes fuse with, or mature into, lysosomes and degrade their materials

Early endosomes have specific protein and lipid compositions that confer organelle identity. One such protein is Rab5, which regulates both early endosome morphology and function (Gorvel et al. 1991; Bucci et al. 1992). Rabs are small GTP-binding membrane proteins that switch between a GTP-bound active state and a GDP-bound inactive state. Rab5 regulates fusion of endocytic vesicles with early endosomes, motility of early endosomes, and generation of phosphotidylinositol-3-phosphate (PtdIns-3-P) and activates signaling pathways from early endosomes (Gorvel et al. 1991, Christoforidis et al. 1999; Murray et al. 2002; Nielsen et al. 1999; Benmerah et al. 2004). Rab5 localizes to the early endosome membrane upon activation by Rabex5, which is a guanine exchange factor (GEF) specific for Rab5 (Horiuchi et al. 1997; Barr and Lambright 2010). The GEF activity of Rabex-5 is promoted by a Rab5 effector, Rabaptin-5, which provides a positive feedback loop for Rab5 activation (Lippe et al. 2001). This allows the recruitment of several Rab effectors on to early endosomes. Key Rab5 effectors are PtdIns-3-P kinases, Vps34 and p150, which are responsible for generating PtdIns-3-P. PtdIns-3-P is the most abundant phosphoinositide on the early endosome membrane and acts as a signal to recruit other effector proteins such as early endosome autoantigen 1 (EEA1), which is essential for homotypic early endosome fusions. EEA1, Rab5, and PtdIns-3-P are three essential components that specify the identity of early endosomes (Mills et al. 1998, 1999).

A switch in GTPases – from Rab5 to Rab7 – on the endosomal membrane marks maturation of early endosomes to late endosomes (Huotari and Helenius 2011). A Rab7 domain forms on early endosomes before maturation to late endosomes leading to a transient, hybrid Rab5/Rab7 endosome (Fig. 1). The Rab7 domains then are removed from the early endosome by fission of endosomal carrier vesicles (Gruenberg and Stenmark 2004). Another possible mechanism is that existing early endosomes gradually mature into late endosomes (Rink et al. 2005). In yeast, the Rab5-to-Rab7 switch has been shown to be regulated by SAND-1/Mon1 that disrupts the Rab5/Rabex-5/Rabaptin-5 complex and actively drives the recruitment of Rab7 onto endosomes (Poteryaev et al. 2010). During endosomal maturation, there is also a switch in the phosphoinositides on the membrane, from PtdIns-3-P to PtdIns-3,5-P by recruitment on PIKfyve. Maturation of endosomes also involves formation of intraluminal vesicles, acidification, and a switch in fusion specificity (Huotari and Helenius 2011).

3. Defects in Endosome Maturation Cause Enlarged Early Endosomes

As described above, endosome maturation is a complex process that requires the concerted action of a series of factors at specific steps. Defects in the recruitment of these factors or the completion of any of these steps of endosome maturation can result in a block in the endocytic pathway. Several studies have identified that defects in the endocytic pathway, particularly those of endosome maturation, are accompanied by an enlargement of early endosomes. Thus, endosome morphology could be used as a marker for early endocytic pathway defects in disease conditions.

Several studies show that interfering with the Rab5-to-Rab7 switch has marked effects on endosome maturation. Hyperactivation of Rab5 by overexpression of wild-type Rab5 leads to giant early endosomes (Bucci et al. 1992; Stenmark et al. 1994). The same effect is seen upon expression of a constitutively active, GTPase-deficient Rab5 mutant, Rab5Q79L. These Enlarged endosomes show both early and late endosome markers indicating that late endosomal markers are being acquired without the loss of early endosomal markers (Hirota et al. 2007; Wegener et al. 2010). Maturing endosomes retained early endosome markers and the ability to fuse with other such endosomes, leading to increased fusion and size of the endosomes (Wegener et al. 2010). Cells expressing constitutively active Rab5 mutant, Rab5Q79L, showed disrupted sorting of transferrin and non-activated EGF receptors in the internal vesicles of enlarged early endosomes, pointing to a functional defect in the endocytic pathway (Ceresa et al. 2001; Wegener et al. 2010). Thus, overactivation of Rab5 leads to defects in both endosome maturation and function.

Overexpression of Rabex-5 and Rabaptin-5, which are required to activate Rab5, is sufficient to cause enlargement of early endosomes (Stenmark et al. 1995; Kälin et al. 2015; Mattera and Bonifacino 2008). Besides, loss of SAND-1 also results in enlarged early endosomes that also express late endosomal markers (Poteryaev et al. 2010). These endosomes have Rabex-5 trapped in them, indicating that SAND-1-mediated removal of Rabex-5 cannot occur anymore. Thus, disruption of the Rab5-to-Rab7 switch during endosome maturation is a possible mechanism that results in enlarged endosomes.

Other mechanisms could also alter endosomal morphology. PIKFyve is a PtdIns-3,5-P2 kinase that converts PtdIns-3-P to PtdIns-3,5-P2 during maturation of endosomes. Although PIKFyve has been traditionally found on late endosomes, a study by Rutherford et al. found that PIKFyve is also enriched on early endosomes (Shisheva 2008; Rutherford et al. 2006). Overexpression of a kinase-dead mutant of PIKFyve or its suppression by siRNA leads to enlarged early and late endosomes (Rutherford et al. 2006). This indicates that lack of PtdIns-3,5-P2 synthesis leads to an increase in the cellular pool of PtdIns-3-P, which promotes homotypic early endosome fusion. Suppression of PIKFyve also results in reduced rate of transport from early endosomes to trans-Golgi network, although receptor sorting to lysosomes or recycling back to plasma membrane remains unaffected (Ikonomov et al. 2003; Rutherford et al. 2006). Thus, PIKFyve can regulate the morphology of early endosomes by regulating PtdIns-3-P levels and the exit of cargo from early endosomes to late endosomes.

Studies by Skjeldal et al. have indicated that disruption of the microtubule network by nocodazole treatment can lead to an increase in the size of early endosomes (Skjeldal et al. 2012). This has been attributed to an increased fusion rate and disruption of fission after microtubule depolymerization. Fusion of early endosomes can result in destabilization of the membrane, which results in fission of smaller endosomal carrier vesicles (Stenmark et al. 1994; Roux et al. 2002). This fission process is dependent on molecular motors such as the kinesin Kif16b and the dynein-dynactin motor (Skjeldal et al. 2012). Thus, conditions that alter the microtubule network also impact endosome maturation and size. It remains to be determined whether this causes a functional defect in the endocytic pathway.

4. Enlarged Endosomes in Disease

Studies of human donor tissue by Cataldo et al. have shown that at the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease, many neurons have increased levels of Aβ peptide and also exhibit enlarged Rab5-positive early endosomes (Cataldo et al. 2000, 2004). Early endosomes are the site where amyloidogenic processing of amyloid precursor protein (APP) occurs to form toxic beta-amyloid (Aβ) peptides. These enlarged early endosomes showed immunoreactivity for other early endosome markers such as EEA1, Rab4, and also Aβ, implying that accumulation of Aβ in early Alzheimer’s disease neurons is correlated with enlarged early endosomes. Studies by Grbovic et al. have shown that enlargement of early endosomes by overexpression of Rab5 in a murine cell line leads to increased accumulation of Aβ peptides in the extracellular medium (Grbovic et al. 2003). Thus, early endosome morphology in neurons appears to be critical for regulating Aβ levels in neurons.

Similar endocytic defects are seen in a mouse model of Down’s syndrome (TS65Dn) (Cataldo et al. 2003), which replicates neurological symptoms seen in Down’s syndrome patients (Galdzicki and Siarey 2003). Most patients with Down’s syndrome develop Alzheimer’s disease pathology by the age of 45. The early onset of Alzheimer’s disease is thought to be a result of three copies of App gene in Down’s syndrome patients. Since it appears that endosomal abnormalities contribute to Alzheimer’s disease pathology, it is likely that the same pathological mechanisms could play a role in Down’s syndrome (Nixon 2005).

Early endosomes in Purkinje neurons of Niemann-Pick Disease type C (NPC) patients are also enlarged (Jin et al. 2004). These cells also have cholesterol accumulation in late endosomes, indicating other defects in the endocytic pathway (Kobayashi et al. 1999). NPC is a lysosomal storage disease caused by mutations in the NPC1 and NPC2 cholesterol transporters. Defective functioning of these proteins causes massive accumulation of cholesterol and sphingolipids resulting in neurological problems and metabolic defects.

We have observed cholesterol accumulation in late endosomes and lysosomes in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) of the Abca4−/− mouse model of Stargardt macular degeneration (Lakkaraju et al. 2007; Toops et al. 2015; Tan et al. 2016). It remains to be determined if enlarged early endosomes and other early endocytic defects are also seen in the RPE of these mice. Early endosome function in the RPE is especially important because this compartment takes in macromolecules and solutes from the choroidal circulation at the basal side and the subretinal space at the apical side. Disruption of early endosome maturation or function can have deleterious consequences for the health of the RPE and the retina because it can interfere with several support functions of the RPE (Toops et al. 2014) and, in a manner analogous to Alzheimer’s disease, contribute to the pathogenesis of macular degeneration.

5. Concluding Remarks

Enlargement of early endosomes has been observed in several disease conditions that have underlying defects in the endocytic pathway, particularly in endosome maturation. However, the exact mechanism leading to this phenotype remains unexplored. Yet, given that endosome enlargement is observed in the early stages of neurodegenerative disease, for example, in early Alzheimer’s patients, it is possible that in age-related, progressive neuropathies, endocytic defects precede other pathologies. Endosome morphology could thus be a useful marker for early endocytic pathway defects in Alzheimer’s disease and other age-related pathologies such as age-related macular degeneration.

Owing to advances in fluorescence microscopy, we are now easily able to observe the dynamics of subcellular organelles using high-speed live-cell imaging. This allows us the unique opportunity to observe the changing morphologies of organelles under different conditions and quantify various parameters such as volume, number, transport, etc. Carefully analyzing the morphology of these organelles might lead us to identify early signs of a disease or discover an unknown defect in the endosomal sorting pathway.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH R01EY023299, Research to Prevent Blindness, and the Retina Research Foundation Rebecca Meyer Brown Professorship

Contributor Information

Gulpreet Kaur, Cellular and Molecular Biology Graduate Training Program, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA, Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA.

Aparna Lakkaraju, McPherson Eye Research Institute, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA, Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA.

References

- Barr F, Lambright DG (2010) Rab GEFs and GAPs. Curr Opin Cell Biol 22:461–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benmerah A (2004) Endocytosis: signaling from endocytic membranes to the nucleus. Curr Biol 14:R314–R316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci C, Parton RG, Mather IH et al. (1992) The small GTPase rab5 functions as a regulatory factor in the early endocytic pathway. Cell 70:715–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter G, Cohen S (1979) Epidermal growth factor. Annu Rev Biochem 48:193–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo AM, Peterhoff CM, Troncoso JC et al. (2000) Endocytic pathway abnormalities precede amyloid beta deposition in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and Down syndrome: differential effects of APOE genotype and presenilin mutations. Am J Pathol 157:277–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo AM, Petanceska S, Peterhoff CM et al. (2003) App gene dosage modulates endosomal abnormalities of Alzheimer’s disease in a segmental trisomy 16 mouse model of down syndrome. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosc 23:6788–6792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo AM, Petanceska S, Terio NB et al. (2004) Abeta localization in abnormal endosomes: association with earliest Abeta elevations in AD and Down syndrome. Neurobiol Aging 25:1263–1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceresa BP, Lotscher M, Schmid SL (2001) Receptor and membrane recycling can occur with unaltered efficiency despite dramatic Rab5(q79l)-induced changes in endosome geometry. J Biol Chem 276:9649–9654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoforidis S, McBride HM, Burgoyne RD et al. (1999) The Rab5 effector EEA1 is a core component of endosome docking. Nature 397:621–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanover A, Schwartz AL, Lodish HF (1983) Sorting and recycling of cell surface receptors and endocytosed ligands: the asialoglycoprotein and transferrin receptors. J Cell Biochem 23:107–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KW, Maxfield FR (1992) Delivery of ligands from sorting endosomes to late endosomes occurs by maturation of sorting endosomes. J Cell Biol 117:301–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KW, McGraw TE, Maxfield FR (1989) Iterative fractionation of recycling receptors from lysosomally destined ligands in an early sorting endosome. J Cell Biol 109:3303–3314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galdzicki Z, Siarey RJ (2003) Understanding mental retardation in Down’s syndrome using trisomy 16 mouse models. Genes Brain Behav 2:167–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorvel JP, Chavrier P, Zerial M et al. (1991) Rab5 controls early endosome fusion in vitro. Cell 64:915–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grbovic OM, Mathews PM, Jiang Y et al. (2003) Rab5-stimulated up-regulation of the endocytic pathway increases intracellular beta-cleaved amyloid precursor protein carboxyl-terminal fragment levels and Abeta production. J Biol Chem 278:31261–31268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenberg J, Stenmark H (2004) The biogenesis of multivesicular endosomes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5:317–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenberg J, Griffiths G, Howell KE (1989) Characterization of the early endosome and putative endocytic carrier vesicles in vivo and with an assay of vesicle fusion in vitro. J Cell Biol 108:1301–1316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota Y, Kuronita T, Fujita H et al. (2007) A role for Rab5 activity in the biogenesis of endosomal and lysosomal compartments. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 364:40–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi H, Lippe R, McBride HM et al. (1997) A novel Rab5 GDP/GTP exchange factor complexed to Rabaptin-5 links nucleotide exchange to effector recruitment and function. Cell 90:1149–1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huotari J, Helenius A (2011) Endosome maturation. EMBO J 30:3481–3500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Mlak K et al. (2003) Active PIKfyve associates with and promotes the membrane attachment of the late endosome-to-trans-Golgi network transport factor Rab9 effector p40. J Biol Chem 278:50863–50871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin LW, Shie FS, Maezawa I et al. (2004) Intracellular accumulation of amyloidogenic fragments of amyloid-beta precursor protein in neurons with Niemann-Pick type C defects is associated with endosomal abnormalities. Am J Pathol 164:975–985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovic M, Sharma M, Rahajeng J et al. (2010) The early endosome: a busy sorting station for proteins at the crossroads. Histol Histopathol 25:99–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalin S, Hirschmann DT, Buser DP et al. (2015) Rabaptin5 is recruited to endosomes by Rab4 and Rabex5 to regulate endosome maturation. J Cell Sci 128:4126–4137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Beuchat MH, Lindsay M et al. (1999) Late endosomal membranes rich in lysobisphosphatidic acid regulate cholesterol transport. Nat Cell Biol 1:113–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakkaraju A, Finnemann SC, Rodriguez-Boulan E (2007) The lipofuscin fluorophore A2E perturbs cholesterol metabolism in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:11026–11031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippe R, Miaczynska M, Rybin V et al. (2001) Functional synergy between Rab5 effector Rabaptin-5 and exchange factor Rabex-5 when physically associated in a complex. Mol Biol Cell 12:2219–2228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattera R, Bonifacino JS (2008) Ubiquitin binding and conjugation regulate the recruitment of Rabex-5 to early endosomes. EMBO J 27:2484–2494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield FR (2014) Role of endosomes and lysosomes in human disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 6:a016931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield FR, McGraw TE (2004) Endocytic recycling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5:121–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellman I (1996) Endocytosis and molecular sorting. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 12:575–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills IG, Jones AT, Clague MJ (1998) Involvement of the endosomal autoantigen EEA1 in homotypic fusion of early endosomes. Curr Biol 8:881–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills IG, Jones AT, Clague MJ (1999) Regulation of endosome fusion. Mol Membr Biol 16:73–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray JT, Panaretou C, Stenmark H et al. (2002) Role of Rab5 in the recruitment of hVps34/p150 to the early endosome. Traffic (Copenhagen, Denmark) 3:416–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen E, Severin F, Backer JM et al. (1999) Rab5 regulates motility of early endosomes on microtubules. Nat Cell Biol 1:376–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon RA (2005) Endosome function and dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol Aging 26:373–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteryaev D, Datta S, Ackema K et al. (2010) Identification of the switch in early-to-late endosome transition. Cell 141:497–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Progida C, Bakke O (2016) Bidirectional traffic between the Golgi and the endosomes – machineries and regulation. J Cell Sci 129:3971–3982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rink J, Ghigo E, Kalaidzidis Y et al. (2005) Rab conversion as a mechanism of progression from early to late endosomes. Cell 122:735–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux A, Cappello G, Cartaud J et al. (2002) A minimal system allowing tubulation with molecular motors pulling on giant liposomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:5394–5399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford AC, Traer C, Wassmer T et al. (2006) The mammalian phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate 5-kinase (PIKfyve) regulates endosome-to-TGN retrograde transport. J Cell Sci 119:3944–3957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shisheva A (2008) PIKfyve: partners, significance, debates and paradoxes. Cell Biol Int 32:591–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skjeldal FM, Strunze S, Bergeland T et al. (2012) The fusion of early endosomes induces molecular-motor-driven tubule formation and fission. J Cell Sci 125:1910–1919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenmark H, Vitale G, Ullrich O et al. (1995) Rabaptin-5 is a direct effector of the small GTPase Rab5 in endocytic membrane fusion. Cell 83:423–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenmark H, Parton RG, Steele-Mortimer O et al. (1994) Inhibition of rab5 GTPase activity stimulates membrane fusion in endocytosis. EMBO J 13:1287–1296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan LX, Toops KA, Lakkaraju A (2016) Protective responses to sublytic complement in the retinal pigment epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:8789–8794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toops KA, Tan LX, Lakkaraju A (2014) A detailed three-step protocol for live imaging of intracellular traffic in polarized primary porcine RPE monolayers. Exp Eye Res 124:74–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toops KA, Tan LX, Jiang Z et al. (2015) Cholesterol-mediated activation of acid sphingomyelinase disrupts autophagy in the retinal pigment epithelium. Mol Biol Cell 26:1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener CS, Malerod L, Pedersen NM et al. (2010) Ultrastructural characterization of giant endosomes induced by GTPase-deficient Rab5. Histochem Cell Biol 133:41–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]