In this study, we found that vaccine refusal persisted after the elimination of nonmedical exemptions from school-entry vaccine requirements in California.

Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES:

California implemented Senate Bill 277 (SB277) in 2016, becoming the first state in nearly 30 years to eliminate nonmedical exemptions from immunization requirements for schoolchildren. Our objectives were to determine (1) the impacts of SB277 on the percentage of kindergarteners entering school not up-to-date on vaccinations and (2) if geographic patterns of vaccine refusal persisted after the implementation of the new law.

METHODS:

At the state level, we analyzed the magnitude and composition of the population of kindergarteners not up-to-date on vaccinations before and after the implementation of SB277. We assessed correlations between previous geographic patterns of nonmedical exemptions and patterns of the remaining entry mechanisms for kindergarteners not up-to-date after the law’s implementation.

RESULTS:

In the first year after SB277 was implemented, the percentage of kindergartners entering school not up-to-date on vaccinations decreased from 7.15% to 4.42%. The conditional entrance rate fell from 4.43% to 1.91%, accounting for much of this decrease. Other entry mechanisms for students not up-to-date, including medical exemptions and exemptions for independent study or homeschooled students, largely replaced the decrease in the personal belief exemption rate from 2.37% to 0.56%. In the second year, the percentage of kindergartners not up-to-date increased by 0.45%, despite additional reductions in conditional entrants and personal belief exemptions. The correlational analysis revealed that previous geographic patterns of vaccine refusal persisted after the law’s implementation.

CONCLUSIONS:

Although the percentage of incoming kindergarteners up-to-date on vaccinations in California increased after the implementation of SB277, we found evidence for a replacement effect.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Recently, California has attempted to increase the number of kindergarteners entering school who are fully up-to-date on required vaccinations. SB277 eliminated the nonmedical exemption option; however, the law also contains several provisions allowing students not up-to-date to enter school.

What This Study Adds:

We found that the percentage of kindergarteners who were not up-to-date on school-entry vaccinations decreased after eliminating nonmedical exemptions. However, we found evidence that nonmedical exemptions were replaced by other mechanisms allowing kindergarteners not up-to-date on vaccinations to enter school.

Large-scale immunization programs remain 1 of the most successful public health interventions.1 In the United States, all kindergartners must receive vaccines before school entry. These requirements are essential to achieving and maintaining high immunization rates and have greatly reduced infectious disease outbreaks.2–4 Although all states allow permanent medical exemptions to vaccination requirements, some states also allow nonmedical exemptions for religious or philosophical reasons. Nonmedical exemption rates have increased nationally over the last decade.5 This trend is more pronounced in states with looser requirements for obtaining them.6 Although overall vaccine coverage remains high,5 the tendency of vaccine refusers to cluster geographically creates pockets of underimmunized children that could compromise herd immunity and have been associated with measles and pertussis outbreaks.7

In recent years, several states have revised their vaccination mandates in response to outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.8 After the “Disneyland” measles outbreak in 2015, California enacted Senate Bill 277 (SB277) in 2016 and became the first state in 30 years to eliminate nonmedical exemptions.9 SB277 was preceded by Assembly Bill 2109 (AB2109), implemented in 2014, which tightened the requirements for obtaining a nonmedical exemption.10 In addition to legislative actions, California’s state and local health departments began an education- and enforcement-based effort in 2015 to promote the proper application of the state’s conditional entrance criteria,11 which allows students who have started but not completed a full series of ≥1 required vaccination to enter school and catch up.

Given that no other state has eliminated nonmedical exemptions recently, a comprehensive examination of the impact of SB277 in California is imperative. The specific provisions of SB277 could have produced a replacement effect, whereby parents who would have used nonmedical exemptions to avoid vaccinating their child instead use alternative mechanisms. First, the law removed the phrase “that contraindicate immunization” from the regulatory language for granting a medical exemption and replaced it with “including, but not limited to, family medical history, for which the physician does not recommend immunization.”9 Although the decision to grant medical exemptions was and remains at the discretion of physicians, this change may have emboldened some physicians to grant them for indications outside of accepted contraindications to vaccination because it is legally acceptable (eg, family medical history).9,12 Second, SB277 exempts kindergarteners attending schools without classroom-based instruction and some students with individualized education programs from vaccination requirements.11

We evaluated state-level changes in both the magnitude and composition of the population of children who were not up-to-date on vaccinations entering school during the first 2 years of SB277 and in the wake of AB2109 and the statewide effort to correctly apply the conditional entrance criteria. In addition, we evaluated the persistence of vaccine refusal by mapping geographic variation in the remaining mechanisms for kindergarteners who were not up-to-date on vaccination to enter school in the second year under SB277 and by comparison with nonmedical exemption rates before SB277.

Methods

We focused on the vaccination status of kindergarteners in 2015, the year before the implementation of SB277 (pre-SB277), and of those who entered in 2016 or 2017 (post-SB277). We collected publicly available state- and county-level data from the California Department of Public Health’s yearly Kindergarten Immunization Assessment reports.13,14 Schools are required by law to report each year,15 and the summary reports contain a near census of California kindergarteners, as detailed in previous studies.10,16

In California, kindergarteners with all required vaccinations at school entry are categorized as up-to-date. A number of entry mechanisms for kindergarteners who were not up-to-date on ≥1 required vaccinations were available and reported by the California Department of Public Health during the study period (Table 1). Before SB277, kindergarteners who were not up-to-date could enter school with a personal belief exemption, permanent medical exemption, or conditional entrance. After SB277, personal belief exemptions were eliminated, but permanent medical exemptions and conditional entrance remained. In 2015, an “overdue” category was created to categorize kindergarteners who were not up-to-date and neither had an exemption nor met the conditional entrance requirements. Overdue students are subject to exclusion from school, but whether they were excluded and whether these students eventually became up-to-date is not reported. SB277 exempted some children from vaccination requirements. First, kindergarteners attending home-based private schools and those in independent study programs without classroom-based instruction are exempt. Second, kindergarteners with individualized education programs who also require special education and are not up-to-date are not prohibited from accessing special education or related services required by their program.17 Kindergarteners who are not up-to-date and meet either of these 2 criteria were termed “exempt” in our analysis.

TABLE 1.

School-Entry Mechanisms for Kindergarteners Who Are Not Up-to-Date on ≥1 Required Vaccination in California

| Mechanism | Reason | Requirement | Years in Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal belief exemption (pre-AB2109) | Nonmedical exemption based on parents’ personal or religious beliefs | Affidavit signed by parents | 2000–2013 |

| Personal belief exemption (post-AB2109 and pre-SB277) | Nonmedical exemption based on parents’ personal or religious beliefs | Affidavit signed by parents and statement signed by a health care provider | 2014–2015 |

| Medical exemption (pre-SB277) | Exemption based on a contraindication to vaccination | Statement signed by a physician with the reason for exemption | 2000–2015 |

| Medical exemption (post-SB277) | Exemption based on a contraindication to vaccination or a physician’s recommendation | Statement signed by a physician with the reason for exemption | 2016–current |

| Conditional entrance | 1. Child has started but has not completed ≥1 series of required vaccinations | 1. Child has received at ≥1 dose in a series for all required vaccinations and the deadline to receive the next dose(s) has not passed | 2000–-current |

| 2. Temporary medical exemption | 2. Child has an affidavit signed by a physician with the reason for temporary medical exemption and expiration date | 2000–-current | |

| Exempt | 1. Child is not subject to immunization requirements | 1. Child attends a home-based private school or an independent study program without classroom-based instructiona | 2016–current |

| 2. Child cannot be denied access to special education services on the basis of immunization status | 2. Child has an individualized education program and requires special educationb | 2016–current | |

| Overdue | Child is not up-to-date on ≥1 series of required vaccines but does not have a personal belief or medical exemption, is not exempt, or does not meet the requirements for conditional entrance | Child is out of compliance and subject to exclusion from school | 2015–current |

“Mechanism” is the term used in the main text, “reason” is a summary of the circumstances when the mechanism is used, and “requirement” summarizes the required materials for entry under the mechanism. When 2 possible reasons are available for a single mechanism, they are enumerated with the corresponding requirement. “Years in effect” is when the particular requirements were in effect (beginning in 2000). Foster children transferring to a new school and homeless children entering school are not subject to the entry requirements and must be admitted even if they are missing their immunization records.

Students in a home-based private school are educated at home. Students in an independent study program generally do not attend classes with other students every day.

Students with an individual education program must be eligible for special education and have been deemed to have a disability and require special education and related services to benefit from the general education program. The exact text in SB277 is, “This section does not prohibit a pupil who qualifies for an individualized education program, pursuant to federal law and Section 56026 of the Education Code, from accessing any special education and related services required by his or her individualized education program.”

Before the analysis, we calculated rates (percentages) to account for differences in the number of kindergarteners entering school each year and among counties. We evaluated the effect of SB277 on vaccination by examining pre- and post-SB277 rates of kindergarteners who were up-to-date and the various entry mechanisms for kindergarteners who were not up-to-date. Changes in conditional entrance rates were examined with regard to the statewide effort before 2015 to correctly apply the conditional entrance criteria. To evaluate the replacement effect due to SB277, we examined the sum of the not–up-to-date entry mechanisms other than conditional entrants and overdue students (called combined replacement mechanisms). Conditional entrants and overdue students were not considered in the combined replacement mechanism summation because this entry mechanism’s definition was not modified by SB277 and these students are required by law to become up-to-date. We stratified the analysis by public and private schools because students in various settings have been shown to have different vaccination and exemption profiles.18,19 Because the data include nearly all California kindergarteners, inferential statistical testing of state-level changes over time was unnecessary.

We mapped the county-level geographic patterns of students who were up-to-date, the separate not–up-to-date entry mechanisms, and combined not up-to-date, given the state’s past geographic heterogeneity in vaccination and exemption rates.2,19–21 We used Pearson’s correlation to test the relationship between pre-SB277 personal belief exemption rates and the not–up-to-date mechanism rates in 2017 (separately and combined). Positive correlation would signal the geographic persistence of vaccine refusal and additional evidence of the replacement effect. As counterfactuals, we compared medical exemption rates pre- and post-SB277, conditional entrance rates pre- and post-SB277, and overdue rates post-SB277 with conditional entrance rates pre-SB277. Positive correlation in the counterfactual tests would signal that post-SB277 geographic patterns were reflections of pre-SB277 conditions carried forward. One county was removed from all tests because of censored data, and 1 was removed for tests of exempt, combined replacement, and not up-to-date because of an outlier exempt rate in 2017 (19.8%) more than 6.5 SDs above the mean. To test the correlation results for sensitivity using 1 year of data acquired during pre-SB277 (2015) and post-SB277 (2017), we used pooled data for 2 and 3 years during pre-SB277 for personal belief exemptions and for 2 years during post-SB277 for the not–up-to-date mechanisms.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Emory University.

Results

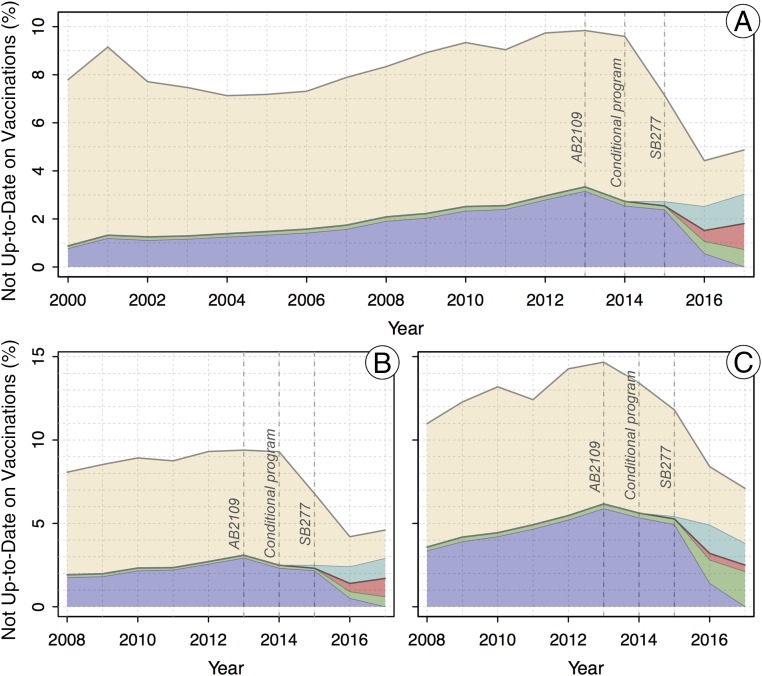

The profile of kindergarteners who were not up-to-date on vaccinations in California from 2000 to 2017 has changed over time, especially in recent years (Fig 1A, Table 2). Until 2013, the percentage of kindergarteners who were not up-to-date on vaccinations generally increased as a result of yearly increases in personal belief exemptions and rates of medical exemptions, whereas conditional entrants stayed roughly consistent. In 2014, the percentage of kindergarteners who were not up-to-date on vaccinations decreased slightly when AB2109 was implemented, and personal belief exemptions decreased despite a small increase in conditional entrants. The not–up-to-date percentage decreased by 2.45% in 2015 when the statewide effort to correctly apply the conditional entrance criteria reduced conditional entrants by 2.43% and personal belief exemptions continued to decrease slightly; overdue students were first reported in 2015 and made up a small portion of all kindergarteners who were not up-to-date on vaccinations. In 2016, the percentage of kindergarteners who were not up-to-date on vaccinations continued to decrease sharply (fell by 2.73%), again because of a large reduction in the number of conditional entrants, which decreased by 2.52%. The 1.81% decrease in personal belief exemptions in 2016 due to SB277 (personal belief exemptions for students entering transitional kindergartens in 2015 remained valid in 2016 and 2017) was nearly fully offset by increases in the combined replacement (0.8%) and overdue (0.82%) mechanisms. The overall not–up-to-date percentage increased in the second year of SB277 because the small reduction in conditional entrants and the near elimination of personal belief exemptions were outweighed by the increases in each of the other not–up-to-date entry mechanisms, which included an increase of 0.84% in the replacement mechanisms. In 2017, 1.81% of all kindergarteners had a medical exemption or were exempt, whereas the combined medical exemption and personal belief exemption rate in 2015 was 2.54%; thus, >70% of these 2 mechanisms were “replaced” by the second year under the new law.

FIGURE 1.

Composition of kindergarteners entering school who are not up-to-date on vaccinations. Percentages of students with a personal belief exemption (purple), medical exemption (green), and exempt (red), overdue (blue), and conditional entrance (tan) are provided for (A) all schools from 2000 to 2017 and for kindergarteners attending (B) public schools and (C) private schools from 2008 to 2017. Dashed lines are placed at the year before the implementation of AB2109 (2013) and SB277 (2015) and the statewide conditional entrance education- and enforcement-based effort (2014) to highlight the changes that occurred directly afterward.

TABLE 2.

Kindergarteners Who Were Not Up-to-Date on Vaccinations in California From 2000 to 2017

| Year | Conditional Entrants | Medical Exemptions | Personal Belief Exemptions | Overdue | Exempt | Not Up-to-Date | Up-to-Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 6.92 | 0.11 | 0.77 | — | — | 7.8 | 92.2 |

| 2001 | 7.83 | 0.14 | 1.19 | — | — | 9.15 | 90.85 |

| 2002 | 6.45 | 0.15 | 1.11 | — | — | 7.71 | 92.29 |

| 2003 | 6.18 | 0.14 | 1.16 | — | — | 7.47 | 92.53 |

| 2004 | 5.74 | 0.15 | 1.24 | — | — | 7.13 | 92.87 |

| 2005 | 5.7 | 0.15 | 1.33 | — | — | 7.18 | 92.82 |

| 2006 | 5.74 | 0.16 | 1.41 | — | — | 7.31 | 92.69 |

| 2007 | 6.14 | 0.18 | 1.56 | — | — | 7.89 | 92.11 |

| 2008 | 6.25 | 0.19 | 1.9 | — | — | 8.34 | 91.66 |

| 2009 | 6.69 | 0.2 | 2.03 | — | — | 8.91 | 91.09 |

| 2010 | 6.82 | 0.19 | 2.33 | — | — | 9.34 | 90.66 |

| 2011 | 6.48 | 0.16 | 2.39 | — | — | 9.04 | 90.96 |

| 2012 | 6.78 | 0.17 | 2.79 | — | — | 9.74 | 90.26 |

| 2013 | 6.5 | 0.19 | 3.15 | — | — | 9.84 | 90.16 |

| 2014 | 6.86 | 0.19 | 2.54 | — | — | 9.6 | 90.4 |

| 2015 | 4.43 | 0.17 | 2.37 | 0.18 | — | 7.15 | 92.85 |

| 2016 | 1.91 | 0.51 | 0.56 | 1.0 | 0.46 | 4.42 | 95.58 |

| 2017 | 1.84 | 0.73 | <0.01 | 1.23 | 1.08 | 4.87 | 95.13 |

Values are presented as the percentages of all kindergarteners entering school each year. —, not applicable.

The statewide changes in not–up-to-date status for kindergarteners attending public schools mirrored changes for all students (Fig 1B) because ∼92.5% of all kindergarteners attended a public school. For private schools, the percentage of kindergarteners who are not up-to-date on vaccinations has decreased steadily since the implementation of AB2109 and has been largely driven by decreases in conditional entrants and personal belief exemptions (Fig 1C). Post-SB277, the medical exemption rate increased in both years, whereas the overdue rate increased in 2016 before falling slightly in 2017.

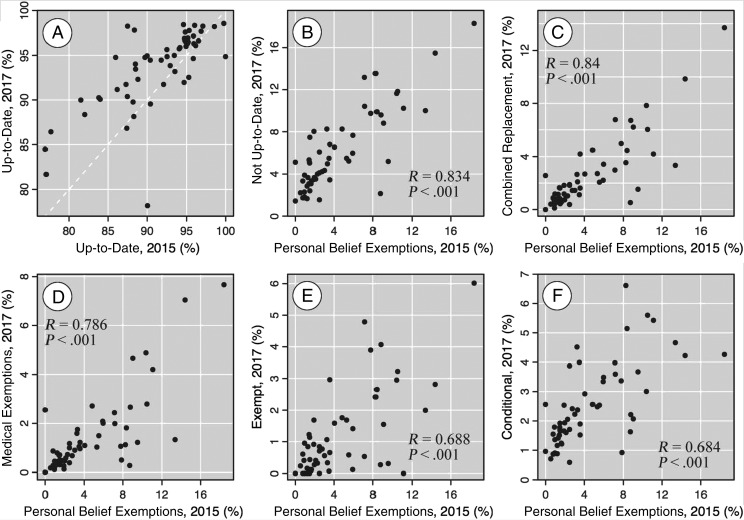

At the county level, the percentage of students up-to-date on vaccinations at school entry increased for most counties since SB277 was implemented (Fig 2A). Yet, numerous counties remained <90% up-to-date in 2017. Pre-SB277 geographic patterns of vaccine hesitancy appeared to persist after SB277 because not–up-to-date, combined replacement (medical exemption plus exempt), medical exemption, and exempt rates in 2017 all demonstrated strong positive correlation with personal belief exemption rates in 2015 (Fig 2 B–E, Supplemental Table 3). Conditional entrance rate in 2017 and personal belief exemption rate were also positively correlated (Fig 2F), which potentially suggests that parents who would have used a personal belief exemption in the past may have initiated but not completed their child’s vaccination by the start of school because of SB277. For the counterfactual analysis, we found that medical exemption rates in 2017 and 2015 were not significantly correlated (R = 0.199; P = .134) and that conditional entrance rates in 2017 and 2015 were significantly correlated (R = 0.426; P < .001), but the magnitude was less than the correlation with personal belief exemption rates. The overdue rate in 2017 was the only not–up-to-date entry mechanism that was not significantly correlated with the pre-SB277 personal belief exemption rate (R = −0.167; P = .902); however, the overdue rate was correlated with the conditional rate in 2015 (R = 0.373; P < .001), suggesting that some overdue kindergarteners may have been classified (incorrectly) as conditional entrants in the past. The results for exempt, combined replacement, and not up-to-date were not appreciably affected by removing the outlier value (Supplemental Table 3). Furthermore, the relationships did not vary substantially when using pooled yearly data in the sensitivity tests (Supplemental Tables 4 through 7).

FIGURE 2.

Scatter plots and correlation results comparing pre- and post-SB277 entry mechanisms for kindergarteners who were not up-to-date. (A) Percentage of children who were up-to-date in 2017 and 2015 with a 1:1 line for reference. Pearson’s correlations (R and P values) for the personal belief exemption rate (2015) and (B) the not–up-to-date rate (2017), (C) the combined replacement mechanism (medical exemptions and exempt) rate (2017), (D) the medical exemption rate (2017), (E) the exempt rate (2017), and (F) the conditional entrance rate (2017) are shown.

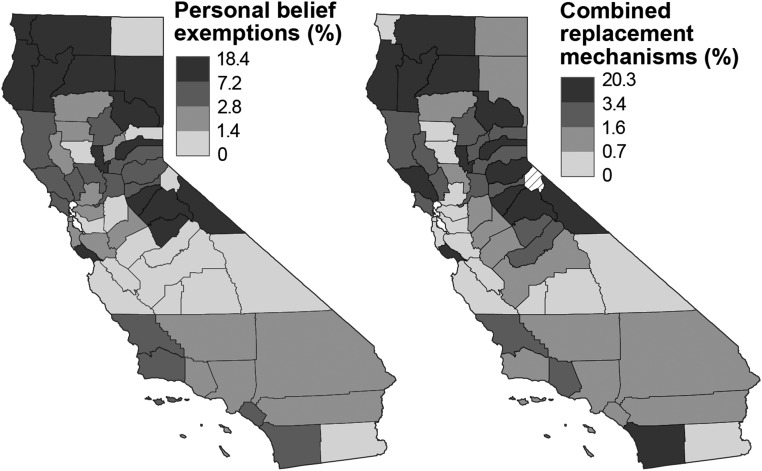

County-level personal belief exemption rates in 2015 and the combined replacement mechanism rates in 2017 are mapped in Fig 3. For both maps, a quantile classification scheme is employed to facilitate relative comparison. The geographic pattern of the replacement mechanisms is similar to the personal belief exemption rate, with higher values found in northern California and the Sierras, moderate values in the south, and lower values in the central regions. Mirroring the correlation results, the geographic distribution of all separate mechanisms for students who were not up-to-date on vaccinations and overall not up-to-date in 2017 is similar to the personal belief exemption rate except for the overdue rate (Supplemental Fig 4).

FIGURE 3.

The personal belief exemption rate in 2015 and the combined replacement mechanism rate in 2017.

Discussion

Although the overall percentage of kindergarteners entering school up-to-date on vaccinations has increased since SB277 was implemented, our analysis reveals a more nuanced picture of the law’s impact. The reduction in kindergarteners who are not up-to-date on vaccinations entering school may owe much to the pre-SB277 education- and enforcement-based effort to correctly apply the conditional entrance requirements. The 2.52% decrease in conditional entrants in the first year under SB277 accounted for much of the overall 2.73% reduction in students who were not up-to-date on vaccinations, and personal belief exemptions appear to have been replaced by the other entry mechanisms for students who were not up-to-date on vaccinations (Fig 1A). Additional evidence of a replacement effect manifested in the second year of SB277 when the overall not up-to-date rate increased by 0.45% despite additional reductions in conditional entrants and personal belief exemptions.

A pressing concern is that medical exemption use continues to increase post-SB277, reaching a level 4 times higher than its pre-SB277 level (Fig 1A). For private school students, the trend was more dramatic; the medical exemption rate rose by nearly 2% in 2 years (Fig 1C) and was roughly 10 times higher than the median rate for US kindergarteners.22 Local health officers and immunization staff in California have expressed concerns over the validity of medical exemptions post-SB277 and physicians who are potentially “selling” them.23 The state-level increases and the high correlation between 2017 medical exemption rates and pre-SB277 personal belief exemption rates (Fig 2D) offer additional evidence that parents have been seeking (and physicians have been providing) medical exemptions under potentially questionable circumstances since SB277 was implemented. Recently, a prominent California physician was put on probation by the state’s medical board for providing an improper medical exemption, and >25 similar complaints are pending against other physicians.24 However, our finding that students exempt from vaccination requirements have also contributed to the replacement effect in California suggests that strategies such as targeting high-profile physicians for providing improper medical exemptions may be appropriate but insufficient.

The positive correlation between pre-SB277 personal belief exemption rates and post-SB277 conditional entrants (Fig 2E) suggests that some parents who would have claimed a personal belief exemption before SB277 may have initiated the series of vaccines to meet the requirements for conditional entrance after the law’s implementation. Yet, data reporting progression toward series completion are not available and we are not able to know whether or when students became fully up-to-date on vaccinations.

Although SB277 eliminated the personal belief exemption option, children who attend a school without classroom-based instruction and some children with individual education programs are exempted from vaccination requirements. As such, the law essentially created a new nonmedical exemption option. Although this is much narrower in scope than a personal belief exemption (available to any student), 1.08% of all California kindergarteners were categorized as not up-to-date on vaccinations under this mechanism in 2017, which was more than double the number in the first year of SB277 (Table 1). In addition, on the basis of the high level of similarity to pre-SB277 personal belief exemption rates (Fig 2E), we suggest that parents are using this new entry mechanism to avoid vaccination. However, because the data do not distinguish among the various scenarios under this entry mechanism, we are unable to further disentangle its effect, warranting additional monitoring and analysis.

The correlation and mapping results (Figs 2 and 3, Supplemental Fig 4) highlight the persistence of parental vaccine hesitancy and refusal in California. Because SB277 contains a grandfather clause, students with a pre-SB277 personal belief exemption can continue attending school until they reach seventh grade (or graduate). Because of consistently high past personal belief exemption rates and the grandfather clause, the school system in numerous regions would continue to have elevated rates of students with personal belief exemptions well after the implementation of SB277.25 Adding more children who are not up-to-date on vaccinations to schools in these regions will further delay the law’s intended effect and may leave them susceptible to disease outbreaks in the near future.

The geographic pattern of overdue students did not appear to reflect the pre-SB277 pattern of parental vaccine refusal; however, the correlation between overdue rates and pre-SB277 conditional entrance rates suggests that overdue students may have been (incorrectly) granted conditional entrance before the statewide effort to correctly apply the conditional entrance requirements. Schools in California have demonstrated inconsistent interpretation and enforcement of immunization requirements,26 and it is unclear whether schools actually excluded students in the overdue category. Regardless, schools now face the difficult task of enforcing SB277 and excluding children who are not up-to-date on vaccinations but lack a medical exemption and do not meet the conditional admittance requirements.

Professional medical associations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics and American Medical Association endorse eliminating nonmedical exemptions.12,27 California was the first state to implement this approach in over 30 years, and our analysis helps to demonstrate how parents, physicians, and schools have reacted under the first 2 years of SB277. The percentage of students entering kindergarten who are up-to-date on vaccinations increased after the implementation of SB277; however, much of the gain in the number of kindergarteners who are up-to-date on vaccinations appears to have been due to a decrease in conditional entrants, likely a result of the pre-SB277 conditional entrance effort. Furthermore, increases in the potential replacement mechanisms for kindergarteners who are not up-to-date on vaccinations (medical exemption and exempt from requirements) have partially offset the decrease in students entering with a personal belief exemption. Given the high correlation between these mechanism rates (both combined and individual) and pre-SB277 personal belief exemption rates, it appears some vaccine-hesitant parents in California are using them as a replacement for personal belief exemptions, creating a replacement effect.

Our analysis is limited in that we only examined 2 years of data after SB277, although a previous analysis revealed that postimplementation trends quickly stabilized.28 Another limitation is that we used personal belief exemption rates as a measure of parental vaccine refusal. Although not a perfect proxy, post-AB2109 personal belief exemption rates in California should largely reflect refusal because they were likely no longer obtained simply out of convenience.8 We do not have individual data on parents’ beliefs; therefore, we could not determine how they would have reacted if SB277 had not been implemented. In addition, the cross-sectional state- and county-level data also limit our ability to establish causality in the relationships between pre-SB277 personal belief exemption rates and post-SB277 rates of the alternative entry mechanisms for students who are not up-to-date on vaccinations; however, we are unable to identify a more compelling argument to explain the findings in light of the counterfactual results.

Conclusions

The percentage of kindergarteners entering school who are fully up-to-date on vaccination increased in the first year under SB277. Although the law was successful in reducing the number of students with personal belief exemptions, our analysis reveals that a replacement effect may have stifled a larger increase in students entering kindergarten who are up-to-date on vaccination. In the second year under the law, this effect appeared to intensify because the percentage of students who are up-to-date on vaccinations decreased. Given these findings, policymakers should consider the various options available to increase vaccination coverage or strategies to minimize potential unintended consequences of eliminating nonmedical exemptions such as the replacement effect observed in California.

Glossary

- AB2109

Assembly Bill 2109

- SB277

Senate Bill 277

Footnotes

Dr Delamater conceptualized and designed the study, performed the analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Ms Pingali drafted the initial manuscript and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs Buttenheim, Salmon, and Klein critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content; Dr Omer conceptualized and designed the study and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: Dr Salmon reports research and consulting support from Pfizer, Merck, and Walgreens; Dr Klein reports research support from Pfizer, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Pasteur, Protein Science (now Sanofi Pasteur), Dynavax, and MedImmune; the other authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by grant R01AI125405 from the National Institutes of Health. The National Institutes of Health had no role in the design and conduct of the study, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or preparation of the final manuscript. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: Dr Salmon reports research and consulting support from Pfizer, Merck, and Walgreens; Dr Klein reports research support from Pfizer, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Pasteur, Protein Science (now Sanofi Pasteur), Dynavax, and MedImmune; the other authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Ten great public health achievements–worldwide, 2001-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(24):814–818 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atwell JE, Van Otterloo J, Zipprich J, et al. Nonmedical vaccine exemptions and pertussis in California, 2010. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):624–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Omer SB, Salmon DA, Orenstein WA, deHart MP, Halsey N. Vaccine refusal, mandatory immunization, and the risks of vaccine-preventable diseases. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(19):1981–1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orenstein WA, Hinman AR. The immunization system in the United States - the role of school immunization laws. Vaccine. 1999;17(suppl 3):S19–S24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw J, Mader EM, Bennett BE, Vernyi-Kellogg OK, Yang YT, Morley CP. Immunization mandates, vaccination coverage, and exemption rates in the United States. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5(6):ofy130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Omer SB, Pan WK, Halsey NA, et al. Nonmedical exemptions to school immunization requirements: secular trends and association of state policies with pertussis incidence. JAMA. 2006;296(14):1757–1763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lieu TA, Ray GT, Klein NP, Chung C, Kulldorff M. Geographic clusters in underimmunization and vaccine refusal. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):280–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buttenheim AM, Jones M, Mckown C, Salmon D, Omer SB. Conditional admission, religious exemption type, and nonmedical vaccine exemptions in California before and after a state policy change. Vaccine. 2018;36(26):3789–3793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.California Legislative Information Bill history: SB-277 public health: vaccinations. 2015. Available at: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billHistoryClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520160SB277. Accessed August 16, 2018

- 10.Jones M, Buttenheim A. Potential effects of California’s new vaccine exemption law on the prevalence and clustering of exemptions. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(9):e3–e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.California Department of Public Health; ShotsForSchool Kindergarten school reporting data. 2015. Available at: www.shotsforschool.org/k-12/reporting-data/. Accessed August 16, 2018

- 12.Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine; Committee on Infectious Diseases; Committee on State Government Affairs; Council on School Health; Section on Administration and Practice Management . Medical versus nonmedical immunization exemptions for child care and school attendance. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20162145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.California Department of Public Health Immunization Branch 2017-2018 Kindergarten Immunization Assessment - Executive Summary. 2018. Available at: https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/CDPH Document Library/Immunization/2017-2018KindergartenSummaryReport.pdf. Accessed August 16, 2018

- 14.California Department of Public Health Immunization Branch 2016-2017 Kindergarten Immunization Assessment - Executive Summary. 2017. Available at: http://eziz.org/assets/docs/shotsforschool/2016-17KindergartenSummaryReport.pdf. Accessed August 16, 2018

- 15.California Legislative Information Health and safety code chapter 1: Educational and Child Care Facility Immunization Requirements [120325 - 120380]. Available at: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displayText.xhtml?lawCode=HSC&division=105.&title=&part=2.&chapter=1.&article. Accessed August 16, 2018

- 16.Delamater PL, Leslie TF, Yang YT. Change in medical exemptions from immunization in California after elimination of personal belief exemptions. JAMA. 2017;318(9):863–864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.California Legislative Information SB-277 public health: vaccinations. 2015. Available at: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520160SB277. Accessed August 16, 2018

- 18.Brennan JM, Bednarczyk RA, Richards JL, Allen KE, Warraich GJ, Omer SB. Trends in personal belief exemption rates among alternative private schools: Waldorf, Montessori, and holistic kindergartens in California, 2000-2014. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(1):108–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richards JL, Wagenaar BH, Van Otterloo J, et al. Nonmedical exemptions to immunization requirements in California: a 16-year longitudinal analysis of trends and associated community factors. Vaccine. 2013;31(29):3009–3013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carrel M, Bitterman P. Personal belief exemptions to vaccination in California: a spatial analysis. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):80–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delamater PL, Leslie TF, Yang YT, Jacobsen KH. An approach for estimating vaccination coverage for communities using school-level data and population mobility information. Appl Geogr. 2016;71:123–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seither R, Calhoun K, Street EJ, et al. Vaccination coverage for selected vaccines, exemption rates, and provisional enrollment among children in kindergarten - United States, 2016-17 school year. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(40):1073–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohanty S, Buttenheim AM, Joyce CM, Howa AC, Salmon D, Omer SB. Experiences with medical exemptions after a change in vaccine exemption policy in California. Pediatrics. 2018;142(5):e20181051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karlamangla S; Los Angeles Times Pushback against immunization laws leaves some California schools vulnerable to outbreaks. 2018. Available at: https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-sears-vaccines-fight-20180713-story.html. Accessed August 3, 2018

- 25.Delamater PL, Leslie TF, Yang YT. A spatiotemporal analysis of non-medical exemptions from vaccination: California schools before and after SB277. Soc Sci Med. 2016;168:230–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wheeler M, Buttenheim AM. Ready or not? School preparedness for California’s new personal beliefs exemption law. Vaccine. 2014;32(22):2563–2569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Medical Association AMA supports tighter limitations on immunization opt outs. 2015. Available at: https://www.ama-assn.org/content/ama-supports-tighter-limitations-immunization-opt-outs. Accessed August 3, 2018

- 28.Omer SB, Allen K, Chang DH, et al. Exemptions from mandatory immunization after legally mandated parental counseling. Pediatrics. 2018;141(1):e20172364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]