Abstract

Background

Dipyrone (metamizole) is a non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug used in some countries to treat pain (postoperative, colic, cancer, and migraine); it is banned in others because of an association with life‐threatening blood agranulocytosis. This review updates a 2001 Cochrane review, and no relevant new studies were identified, but additional outcomes were sought.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and adverse events of single dose dipyrone in acute postoperative pain.

Search methods

The earlier review searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, LILACS and the Oxford Pain Relief Database to December 1999. For the update we searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE,EMBASE and LILACS to February 2010.

Selection criteria

Single dose, randomised, double‐blind, placebo or active controlled trials of dipyrone for relief of established moderate to severe postoperative pain in adults. We included oral, rectal, intramuscular or intravenous administration of study drugs.

Data collection and analysis

Studies were assessed for methodological quality and data extracted by two review authors independently. Summed total pain relief over six hours (TOTPAR) was used to calculate the number of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief. Derived results were used to calculate, with 95% confidence intervals, relative benefit compared to placebo, and the number needed to treat (NNT) for one participant to experience at least 50% pain relief over six hours. Use and time to use of rescue medication were additional measures of efficacy. Information on adverse events and withdrawals was collected.

Main results

Fifteen studies tested mainly 500 mg oral dipyrone (173 participants), 2.5 g intravenous dipyrone (101), 2.5 g intramuscular dipyrone (99); fewer than 60 participants received any other dose. All studies used active controls (ibuprofen, paracetamol, aspirin, flurbiprofen, ketoprofen, dexketoprofen, ketorolac, pethidine, tramadol, suprofen); eight used placebo controls.

Over 70% of participants experienced at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours with oral dipyrone 500 mg compared to 30% with placebo in five studies (288 participants; NNT 2.4 (1.9 to 3.2)). Fewer participants needed rescue medication with dipyrone (7%) than with placebo (34%; four studies, 248 participants). There was no difference in participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief with 2.5 g intravenous dipyrone and 100 mg intravenous tramadol (70% vs 65%; two studies, 200 participants). No serious adverse events were reported.

Authors' conclusions

Based on very limited information, single dose dipyrone 500 mg provides good pain relief to 70% of patients. For every five individuals given dipyrone 500 mg, two would experience this level of pain relief who would not have done with placebo, and fewer would need rescue medication, over 4 to 6 hours.

Keywords: Humans; Acute Disease; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal/administration & dosage; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal/adverse effects; Dipyrone; Dipyrone/administration & dosage; Dipyrone/adverse effects; Pain, Postoperative; Pain, Postoperative/drug therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Single‐dose dipyrone for the treatment of acute postoperative pain

Dipyrone is a popular medicine for pain relief in many countries and is used to treat postoperative pain, colic pain, cancer pain and migraine. Other countries (e.g. USA, UK, Japan) have banned its use because of an association with potentially life‐threatening blood disorders such as agranulocytosis. There was too little information available to draw any conclusions about most of the doses and routes of administration of dipyrone used in these studies. A single 500 mg oral dose of dipyrone provided at least 50% pain relief to adults with moderate or severe postoperative pain, with similar efficacy to ibuprofen 400 mg. A single 2.5 g intravenous dose was equivalent to 100 mg intravenous tramadol for at least 50% pain relief. Adverse effects were poorly reported, but no serious events or adverse event withdrawals were reported.

Background

This is an update of a review published in The Cochrane Library in Issue 3, 2001 (Edwards 2001).

Acute pain occurs as a result of tissue damage either accidentally due to an injury or as a result of surgery. Acute postoperative pain is a manifestation of inflammation due to tissue injury. The management of postoperative pain and inflammation is a critical component of patient care. This is one of a series of reviews whose aim is to increase awareness of the range of analgesics that are potentially available (depending on licensing in different countries), and present evidence for relative analgesic efficacy through indirect comparisons with placebo, in very similar trials performed in a standard manner, with very similar outcomes, and over the same duration. Such relative analgesic efficacy does not in itself determine choice of drug for any situation or patient, but guides policy‐making at the local level. The series includes well established analgesics such as paracetamol (Toms 2008), naproxen (Derry C 2009a), diclofenac (Derry P 2009), and ibuprofen (Derry C 2009b), newer cyclo‐oxygenase‐2 selective analgesics, such as celecoxib (Derry 2008), etoricoxib (Clarke 2009), and parecoxib (Lloyd 2009), and opioid/paracetamol combinations, such as paracetamol and codeine (Toms 2009).

Acute pain trials

Single dose trials in acute pain are commonly short in duration, rarely lasting longer than 12 hours. The numbers of participants are small, allowing no reliable conclusions to be drawn about safety. To show that the analgesic is working, it is necessary to use placebo (McQuay 2005). There are clear ethical considerations in doing this. These ethical considerations are answered by using acute pain situations where the pain is expected to go away, and by providing additional analgesia, commonly called rescue analgesia, if the pain has not diminished after about an hour. This is reasonable, because not all participants given an analgesic will have significant pain relief. Approximately 18% of participants given placebo will have significant pain relief (Moore 2006), and up to 50% may have inadequate analgesia with active medicines. The use of additional or rescue analgesia is hence important for all participants in the trials. Clinical trials measuring the efficacy of analgesics in acute pain have been standardised over many years. Trials have to be randomised and double blind. Typically, in the first few hours or days after an operation, patients develop pain that is moderate to severe in intensity, and will then be given the test analgesic or placebo. Pain is measured using standard pain intensity scales immediately before the intervention, and then using pain intensity and pain relief scales over the following 4 to 6 hours for shorter acting drugs, and up to 12 or 24 hours for longer acting drugs. Pain relief of half the maximum possible pain relief or better (at least 50% pain relief) is typically regarded as a clinically useful outcome. For patients given rescue medication it is usual for no additional pain measurements to be made, and for all subsequent measures to be recorded as initial pain intensity or baseline (zero) pain relief (baseline observation carried forward). This process ensures that analgesia from the rescue medication is not wrongly ascribed to the test intervention. In some trials the last observation is carried forward, which gives an inflated response for the test intervention compared to placebo, but the effect has been shown to be negligible over 4 to 6 hours (Moore 2005). Patients usually remain in the hospital or clinic for at least the first 6 hours following the intervention, with measurements supervised, although they may then be allowed home to make their own measurements in trials of longer duration.

Dipyrone, or metamizole, is a non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAID). It was first synthesised in 1920 in Germany, and the drug was launched there in 1922. NSAIDs have pain‐relieving, antipyretic and anti‐inflammatory properties, and have proven efficacy following day surgery and minor surgery. They reversibly inhibit cyclooxygenase (prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase), the enzyme mediating production of prostaglandins (PGs) and thromboxane A2. These mechanisms may be involved with some of the known problems associated with NSAIDs, including gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, renal and hypertensive adverse effects (Fitzgerald 2001; Hawkey 1999; Hawkey 2002; Patrono 2009).

Dipyrone is a controversial analgesic. It is used most commonly to treat postoperative pain, colic pain, cancer pain and migraine, and in many countries (e.g. Russia, Spain, Mexico, and in many parts of South‐America, Asia, and Africa) it remains a popular non‐opioid first line analgesic (PASG 1999), either by prescription only, as in Germany and Spain, or over the counter. In others it has been banned (e.g. USA, UK, Japan, Canada, and parts of Europe and Scandinavia) because of its association with potentially life‐threatening blood dyscrasias such as agranulocytosis. In countries where it is banned it may still be available and widely used by immigrant populations (Bonkowsky 2002). It is sold under many different brand names, including Analgin and Novalgin, and is also known in some areas as "Mexican aspirin". In addition to use as a single agent, it is commonly used in combination products.

There is a wealth of literature on agranulocytosis associated with dipyrone: a large, international study found vastly differing rates of agranulocytosis in the eleven countries in which information was collected (IAAAS 1986). There are a number of published criticisms of this study (Kramer 1988). None of these criticisms mention the importance of size (of the population studied and the analyses) for detecting true incidence rates for rare events. Size is an important criterion of study validity (Moore 1998). A report from Sweden suggested a rate of 1 case of agranulocytosis in 1439 prescriptions (Hendenmalm 2002), although there may be differences between populations in their susceptibility to agranulocytosis (Merida Rodrigo 2009). A recent review of non chemotherapy drug‐induced agranulocytosis identified dipyrone in six definite and five probable high quality case reports, with a median time to onset of only two days (Andersohn 2007). While the risk of agranulocytosis remains uncertain (Edwards 2002b), dipyrone is one of the 10 drugs most commonly associated with it (Andersohn 2007).

The use of dipyrone (metamizole) has been reported to be associated with other potentially serious adverse events such as chronic interstitial nephritis and gastro‐intestinal disturbances (Zukowski 2009), as well as allergic/idiosyncratic reactions like anaphlaxis, bronchospasm, toxic epidermal necrolysis (Arellano 1990).

The earlier review, which searched to 1999, identified a relatively small number of studies of generally moderate methodological quality, so that conclusions about efficacy, and tolerability, were not robust. The update was undertaken to see if there were now more data available to give a more robust estimate of efficacy, and because additional measures of efficacy derived from use of rescue medication are now routinely sought in this type of study (Moore 2005).

Objectives

To evaluate the analgesic efficacy and safety of dipyrone in the treatment of acute postoperative pain, using methods that permit comparison with other analgesics evaluated in the same way, and criteria of efficacy recommended by an in‐depth study at the individual patient level (Moore 2005).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Reports were included if they were published randomised placebo or active controlled, double blind studies of a single dose of dipyrone, with a minimum of 10 participants per treatment arm. Multiple dose studies were included if appropriate data from the first dose were available, and cross‐over studies were included provided that data from the first arm were presented separately.

Abstracts, review articles, case reports, and clinical observations were excluded, as were reports that did not clearly state that the interventions had been randomly allocated, were concerned with other pain conditions, or used experimental pain or volunteer participants.

Types of participants

Male or female patients (aged 15 years and above) experiencing postoperative pain of moderate to severe intensity, which is defined as ≥3 on a 4 point categorical scale or ≥30 mm on a 100 mm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS).

Types of interventions

Single dose dipyrone compared with placebo or an active comparator, administered postoperatively when pain intensity was moderate or severe. Oral, rectal, intravenous and intramuscular routes of administration were included.

Types of outcome measures

Data were collected on the following:

patient characteristics;

pain model (dental or other type of surgery);

patient reported pain at baseline (physician, nurse, or carer reported pain will not be included in the analysis);

patient‐reported pain relief and/or pain intensity expressed hourly over four to six hours using validated pain scales (pain intensity and pain relief in the form of visual analogue scales (VAS) or categorical scales, or both), or reported total pain relief (TOTPAR) or summed pain intensity difference (SPID) at four to six hours;

number of participants using rescue medication;

time to use of rescue medication, and the time of assessment;

withdrawals ‐ all cause, adverse event;

adverse events ‐ participants experiencing one or more, and any serious adverse event, and the time of assessment.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the following databases:

Cochrane CENTRAL, Issue 3 1999 for the original review, and Issue 1, 2010 for the update;

MEDLINE (via OVID), 1966 to October 1999 for the original review, and February 2010 for the update;

EMBASE (via OVID), 1974 to October 1999 for the original review, and February 2010 for the update;

LILACS (via Brazilian Cochrane Centre) to December 1999 for the original review, and February 2010 for the update;

Oxford Pain Relief Database (Jadad 1996a).

Reference lists of retrieved studies were also manually searched.

Search strategies for MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL can be found in Appendix 1, Appendix 2 and Appendix 3 respectively.

Language

No language restriction was applied.

Additional sources

For the original review attempts were made to identify additional studies by contact with authors, experts, pharmaceutical companies and the Brazilian and San Antonio Cochrane Centres. The website of the National Institute of Health (http://clinicaltrials.gov) was searched to identify ongoing clinical trials on dipyrone. Where possible, authors of reports were contacted to obtain additional relevant information (e.g. number of patients assessed) if this was not provided. Pharmaceutical companies known to manufacture dipyrone were contacted for unpublished studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently carried out searches, reviewed the titles and abstracts retrieved, and agreed on which reports should be retrieved in full for assessment for inclusion in the review. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with the third author.

Quality assessment

Two review authors independently assessed the included studies for methodological quality using a five‐point scale (Jadad 1996b).

The scale used is as follows: Is the study randomised? If yes ‐ one point; Is the randomisation procedure reported and is it appropriate? If yes add one point, if no deduct one point; Is the study double blind? If yes then add one point; Is the double blind method reported and is it appropriate? If yes add 1 point, if no deduct one point; Are the reasons for patient withdrawals and dropouts described? If yes add one point.

A Risk of bias table was completed for the categories of randomisation, allocation concealment, and blinding.

The results are described in the 'Methodological quality of included studies' section below, and 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Data management

Data for outcomes reported in the earlier review were checked by one author. Data for new outcomes were extracted by two review authors and recorded on a standard data extraction form. Data suitable for pooling were entered into RevMan 5.0.

Data analysis

QUOROM guidelines were followed where appropriate (Moher 1999). For efficacy analyses we used the number of participants in each treatment group who were randomised, received medication, and provided at least one post‐baseline assessment. For safety analyses we used number of participants randomised to each treatment group. Analyses were planned for different doses (where there were at least 200 participants). Sensitivity analyses were planned for pain model (dental versus other postoperative pain), trial size (39 or fewer versus 40 or more per treatment arm), and quality score (2 versus 3 or more).

Primary outcome: Number of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief

For each study, mean TOTPAR (total pain relief) or SPID (summed pain intensity difference) for active and placebo groups were converted to %maxTOTPAR or %maxSPID by division into the calculated maximum value (Cooper 1991). The proportion of participants in each treatment group who achieved at least 50%maxTOTPAR was calculated using verified equations (Moore 1996; Moore 1997a; Moore 1997b). These proportions were then converted into the number of participants achieving at least 50%maxTOTPAR by multiplying by the total number of participants in the treatment group. Information on the number of participants with at least 50%maxTOTPAR for active treatment and placebo was then used to calculate relative benefit (RR) and number needed to treat to benefit (NNT).

Pain measures accepted for the calculation of TOTPAR or SPID were:

five‐point categorical pain relief (PR) scales with comparable wording to "none, slight, moderate, good or complete";

four‐point categorical pain intensity (PI) scales with comparable wording to "none, mild, moderate, severe";

Visual analogue scales (VAS) for pain relief;

VAS for pain intensity;

five‐point categorical global scale with the wording "poor, fair, good, very good, excellent" (Collins 2001).

Secondary outcomes:

1. Use of rescue medication. Numbers of participants requiring rescue medication were used to calculate NNTs to prevent use of rescue medication for treatment and placebo groups. Median (or mean) time to use of rescue medication was used to calculate the weighted mean of the median (or mean) for the outcome. Weighting was by number of participants.

2. Adverse events. Numbers of participants reporting adverse events for each treatment group were used to calculate relative risk (RR) and numbers needed to treat to harm (NNH) estimates for:

any adverse event

any serious adverse event (as reported in the study)

withdrawal due to an adverse event

3. Other withdrawals. Withdrawals for reasons other than lack of efficacy (participants using rescue medication ‐ see above) and adverse events were noted.

Relative benefit or risk estimates were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using a fixed‐effect model (Morris 1995). NNT or NNH with 95% CI were calculated using the pooled number of events by the method of Cook and Sackett (Cook 1995). A statistically significant difference from control was assumed when the 95% CI of the relative benefit did not include one.

Homogeneity of studies was assessed visually (L'Abbe 1987). The z test (Tramer 1997) would be used to determine if there was a significant difference between NNTs for different doses of active treatment, or between groups in the sensitivity analyses.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

Different doses of dipyrone were analysed separately. Sub‐group analyses were planned to determine the effect of presenting condition (pain model), and sensitivity analysis was planned for high versus low (two or fewer versus three or more) quality studies.

A minimum of two studies and 200 participants had to be available for any statistical analysis (Moore 1998).

Results

Description of studies

The original searches identified 15 studies that met the inclusion criteria. No new studies for inclusion were identified by the updated searches, but we were unable to obtain one potentially relevant study (Shi 2003). It is unclear whether this study is in postoperative pain as the keywords mention only fever; details are in Studies awaiting classification. Two reports were identified by the original searches that could not be obtained. One of these (Handwerker 1990) appears to be a review chapter, and we consider that it is unlikely to report an original study not identified by the searches. The other (Mitev 1980) is an abstract, so does not satisfy inclusion criteria. One study (Pinto 1984) included one or more participants aged 14 years, but was nonetheless included. Eighty‐one other studies were excluded after obtaining and reading the full report, including three identified in the updated searches; details are in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Eight included studies used both placebo and active controls (Bhounsule 1990; Boraks 1987; Miguel Rivero 1997; Olson 1999; Pinto 1984; Rubinstein 1986; Sakata 1986; Pereira 1986); the active controls in these studies were oral ibuprofen 400 mg, paracetamol (500 mg or 1 g), aspirin 600/650 mg, flurbiprofen 50 mg and ketoprofen (25 mg or 50 mg). Seven studies used an active control only (Bagan 1998; Gonzalez Garcia 1994; Ibarra 1993; Mendl 1992; Patel 1980; Rosas Pérez 1986; Stankov 1995). The active control drugs in these studies were oral dexketoprofen (12.5 mg or 25 mg), oral ketorolac 10 mg, intramuscular ketorolac 30 mg, intramuscular pethidine 100 mg, intravenous tramadol 100 mg and rectal suprofen 300 mg.

Oral dipyrone 500 mg was used in 173 participants in six studies (Bhounsule 1990; Boraks 1987; Gonzalez Garcia 1994; Olson 1999; Pinto 1984; Rubinstein 1986), 575 mg in 40 participants in one study (Bagan 1998), and 1 g in 57 participants in two studies (Sakata 1986; Pereira 1986). Dipyrone 1 g suppositories were used in 20 participants in one study (Rosas Pérez 1986), 2 g intramuscular in 35 participants in one study (Miguel Rivero 1997), 2.5 g intramuscular in 99 participants in two studies (Ibarra 1993; Patel 1980), and 2.5 g intravenous in 101 participants in two studies (Mendl 1992; Stankov 1995).

Two studies were carried out in participants who had undergone dental surgery (Bagan 1998; Boraks 1987), five following orthopaedic surgery (Gonzalez Garcia 1994; Ibarra 1993; Miguel Rivero 1997; Sakata 1986; Pereira 1986), three following episiotomy (Bhounsule 1990; Ibarra 1993; Olson 1999), one following tonsillectomy (Pinto 1984), and four following laparotomy (Patel 1980) or abdominal or urological surgery (Mendl 1992; Rubinstein 1986; Stankov 1995).

Two studies (Bagan 1998; Miguel Rivero 1997) used multiple doses of study medication, but reported outcomes for the first dose separately. All studies reported single dose efficacy over 4 to 6 hours.

Full details of included studies are in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

Methodological quality of included studies

All included studies were both randomised and double blind. Six studies (Bhounsule 1990; Boraks 1987; Mendl 1992; Patel 1980; Rosas Pérez 1986; Sakata 1986) scored the minimum of 2/5 on the Oxford Quality Scale, while five scored 3/5 (Gonzalez Garcia 1994; Ibarra 1993; Olson 1999; Pinto 1984; Pereira 1986) and four score 4/5 (Bagan 1998; Miguel Rivero 1997; Rubinstein 1986; Stankov 1995). Few studies adequately described the methods used to ensure randomisation and blinding, and eight did not adequately report on withdrawals.

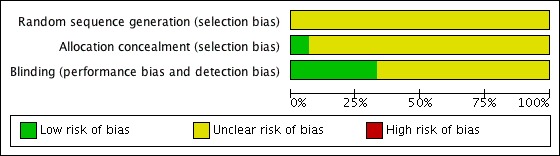

A Risk of bias table was completed for randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding criteria. While no studies were at high risk of bias, the lack of detail for the methods used meant that no study was considered at low risk of bias (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Effects of interventions

Eight studies compared dipyrone (500 mg, 1 g, 2 g) with placebo over 4 to 6 hours (Boraks 1987; Bhounsule 1990; Miguel Rivero 1997; Pereira 1986; Olson 1999; Pinto 1984; Rubinstein 1986; Sakata 1986). Only the 500 mg dose of oral dipyrone provided sufficient data for statistical analysis.

Number of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief

Dipyrone 500 mg (oral) versus placebo

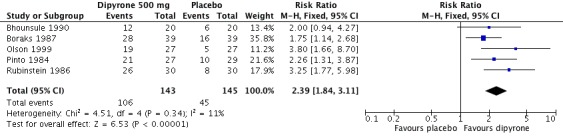

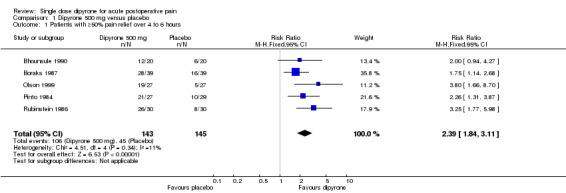

Five studies compared oral dipyrone 500 mg with placebo over 4 to 6 hours (Bhounsule 1990; Boraks 1987; Olson 1999; Pinto 1984; Rubinstein 1986). There were 288 participants in the comparison.

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours with dipyrone 500 mg was 73% (106/143; range 60% to 87%)

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours with placebo was 32% (45/145; range 19% to 41%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 2.3 (1.8 to 3.1), giving an NNT for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours of 2.4 (1.9 to 3.1) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Dipyrone 500 mg versus placebo, outcome: 1.1 Patients with ≥50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses of the primary outcome

There were insufficient data to carry out subgroup analyses on the primary outcome for route of administration or pain model, or to carry out sensitivity analysis for study quality.

Dipyrone 1 g (oral) versus placebo

Two studies compared oral dipyrone 1 g with placebo (Sakata 1986; Pereira 1986); 38/57 (67%) of those treated with dipyrone 1 g experienced ≥50% pain relief over 4 hours compared with 10/56 (18%) treated with placebo. There were insufficient data for statistical analysis.

Dipyrone 2 g (IM) versus placebo

One study compared intramuscular dipyrone 2 g with placebo (Miguel Rivero 1997); 26/35 of those treated with intramuscular dipyrone 2 g experienced ≥50% pain relief over 5 hours compared with 16/35 treated with placebo. There were insufficient data for statistical analysis.

Dipyrone 500 mg (oral) versus paracetamol 500‐600 mg

Three studies compared oral dipyrone 500 mg with paracetamol 500 mg (Pinto 1984; Rubinstein 1986) or 600 mg (Bhounsule 1990); 58/77 (75%) of those treated with dipyrone 500 mg experienced ≥50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours compared with 53/79 (67%) treated with paracetamol 500 mg or 600 mg. There were insufficient data for statistical analysis.

Dipyrone 500 mg (oral) versus aspirin 600‐650 mg

Two studies compared oral dipyrone 500 mg with aspirin 600 mg (Bhounsule 1990) or 650 mg (Boraks 1987); 39/59 (66%) of those treated with dipyrone 500 mg experienced ≥50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours compared with 30/61 (49%) treated with aspirin 600 mg or 650 mg. There were insufficient data for statistical analysis.

Dipyrone 1 g (oral) versus paracetamol 1 g

Two studies compared oral dipyrone 1 g with paracetamol 1 g (Sakata 1986; Pereira 1986); 38/57 (67%) of those treated with dipyrone 1 g experienced ≥50% pain relief over 4 hours compared with 38/58 (66%) treated with paracetamol 1 g. There were insufficient data for statistical analysis.

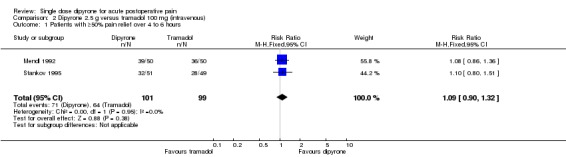

Dipyrone 2.5 g (intravenous) versus tramadol 100 mg

Two studies compared intravenous dipyrone 2.5 g with intravenous tramadol 100 mg (Mendl 1992; Stankov 1995).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over 4 hours with dipyrone 2.5 g was 70% (71/101; range 63% to 78%)

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over 4 hours with placebo was 65% (64/99; range 57% to 72%)

The relative risk was 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3). There was no significant difference between treatments (Analysis 2.1)

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 Dipyrone 2.5 g versus tramadol 100 mg (intravenous), Outcome 1 Patients with ≥50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

There were no other comparisons in which the same dose and route of administration of dipyrone were compared with either placebo or an active comparator in more than one study. Results for individual studies are available in Summary of efficacy results in individual studies (Appendix 5).

Number of participants using rescue medication

The number of participants needing rescue medication during the study period was not reported in five studies (Bhounsule 1990; Mendl 1992; Patel 1980; Rosas Pérez 1986; Sakata 1986). It is unclear whether there were no withdrawals for this reason in these studies.

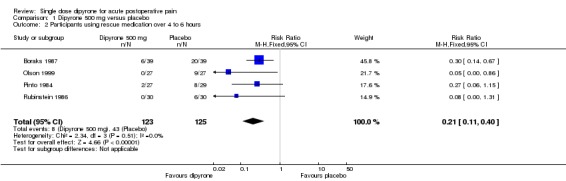

Dipyrone 500 mg (oral) versus placebo

Four studies comparing dipyrone 500 mg with placebo provided data on the number of participants using rescue medication before the end of the study (4 to 6 hours) (Boraks 1987; Olson 1999; Pinto 1984; Rubinstein 1986).

The proportion of participants using rescue medication over 4 to 6 hours with dipyrone 500 mg was 7% (8/123; range 0% to 15%)

The proportion of participants using rescue medication over 4 to 6 hours with placebo was 34% (43/125; range 20% to 51%)

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 0.19 (0.09 to 0.38), giving an NNT to prevent use of rescue medication over 4 to 6 hours of 3.6 (2.7 to 5.4) (Analysis 1.2).

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 Dipyrone 500 mg versus placebo, Outcome 2 Participants using rescue medication over 4 to 6 hours.

There were insufficient data for analysis of any other dose or route of administration of dipyrone for this outcome. Results for individual studies are available in Summary of efficacy outcomes in individual studies (Appendix 5).

Time to use of rescue medication

One study comparing oral dipyrone 500 mg with placebo following episiotomy (Olson 1999) reported a mean time to use of rescue medication of >6 hours for dipyrone, 6 hours or more for ketoprofen 25 mg and 50 mg, and 5.3 hours for placebo. Another study using oral dipyrone 575 mg following dental surgery (Bagan 1998) reported a median time to use of rescue medication of >6 hours for dipyrone, dexketoprofen 12.5 mg and dexketoprofen 25 mg. One other study using intramuscular dipyrone 2 g following orthopaedic surgery (Miguel Rivero 1997) reported a median time to use of rescue medication of 2.6 hours for dipyrone, 3.5 hours for ibuprofen arginine 400 mg and 1.8 hours for placebo.

Adverse events

One study (Sakata 1986) did not mention adverse events, and another (Pereira 1986) reported only that the study medication was "well tolerated". Reporting of adverse events in the other studies was inconsistent, with some reporting only those that were considered related to the test drug, or that were "clinically relevant". Few events were reported, and no analysis could be carried out for participants experiencing one or more adverse events. No serious adverse events were reported. Details of events in individual studies are provided in Summary of adverse events and withdrawals (Appendix 6).

Withdrawals

No adverse event withdrawals were reported in any of the studies. Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy are reported above under 'Use of rescue medication'. Eight studies (Bhounsule 1990; Boraks 1987; Mendl 1992; Patel 1980; Pinto 1984; Rosas Pérez 1986; Sakata 1986; Pereira 1986) did not specifically report on all cause withdrawals.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This update found no new studies, so there remain only nine studies that use various doses of dipyrone (500 mg to 2.5 g), administered by different routes (oral, suppository, intramuscular and intravenous), following different surgical procedures, and compared with placebo and/or a variety of active comparators. The original studies provided some additional data for numbers of participants using rescue medication, but very little on the mean or median time to its use, which is a useful indicator of duration of analgesia.

For the primary outcome of at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours, there were sufficient data from placebo controlled comparisons to analyse only oral dipyrone 500 mg versus placebo (288 participants). The relative benefit was 2.3 (1.8 to 3.0), giving an NNT of 2.4 (1.9 to 3.2). For every five individuals treated, two would experience at least 50% pain relief who would not have done so with placebo. For the same comparison (248 participants), the relative risk of needing rescue medication within 4 to 6 hours was 0.19 (0.09 to 0.38), giving an NNT to prevent use of rescue medication of 3.6 (2.7 to 5.4). For every seven individuals treated, two would not need rescue medication who would have done with placebo.

Results from studies using different doses and routes of administration were all consistent with a benefit of dipyrone over placebo.

For active controlled comparisons there were sufficient data to analyse only the comparison of 2.5 g intravenous dipyrone with 100 mg intravenous tramadol in two studies (200 participants). The relative benefit was 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3), indicating no significant difference between treatments. Only one of these studies provided data on use of rescue medication.

Indirect comparisons of NNTs for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours in reviews of other analgesics using identical methods indicate that dipyrone has similar efficacy to ibuprofen 400 mg (Derry 2009; NNT 2.5 (2.4 to 2.6)) and paracetamol 1000 mg plus codeine 60 mg (Toms 2009; NNT 2.2 (1.8 to 2.9)), is more effective than paracetamol 1000 mg alone (Toms 2008; NNT 3.6 (3.4 to 4.0)) and less effective than etoricoxib 120 mg (Clarke 2009; 1.9 (1.7 to 2.1)).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The studies involved participants who had undergone a diverse range of surgical procedures, from episiotomy to total hip replacement. They probably represent the adult populations likely to be given the drug, although older people, pregnant women, and those with contraindications were excluded form the studies. Relatively few had undergone dental extractions, which are commonly used in these single dose studies.

Quality of the evidence

Overall the methodological quality of the studies was moderate; all studies had to be randomised and double blind to satisfy inclusion criteria, but half did not report on withdrawals, and few gave details of the randomisation and blinding procedures, or of how missing data were handled. Treatment group sizes were small, so that even when several studies contributed data for an outcome, the number of events was small, and confidence in the result must therefore be limited.

All studies enrolled participants with established pain following surgery, with pain levels sufficient to demonstrate reduction, or otherwise, due to treatment. Adverse event data were not well reported, with no information on whether data were collected after use of rescue medication (which may cause its own adverse events). The small size of each treatment arm and small number of studies means that this review is underpowered to address the safety of dipyrone.

Potential biases in the review process

The included studies were identified from a comprehensive search of published papers, and standard methods have been used for analysis. A number of studies (10) were excluded from the original review because they presented data in a way that this review could not utilise, or used non‐standard measurement scales. It is possible, but unlikely, that these studies could have given different results that would have changed the findings of this review.

We can estimate the number of participants in studies with zero effect (relative benefit of 1) required in order to change the NNT for at least 50% pain relief to an unacceptably high level (in this case 10) (Moore 2008). Data from over 900 participants in such studies would be required, and it is unlikely that such data exist.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We are not aware of any other systematic reviews or meta‐analyses of dipyrone in acute postoperative pain. A recent narrative review (Jage 2008) reported that dipyrone has similar efficacy to other NSAIDs and intravenous paracetamol, has a notable spasmolytic effect, and is rarely associated with agranulocytosis and other disorders of haematopoiesis.

Authors' conclusions

This analysis is based on information from relatively few patients and the quantitative estimates produced are not robust. The results should be interpreted with caution. It appears that dipyrone is an effective analgesic and an oral dose of 500 mg may be of similar efficacy to oral ibuprofen 400 mg when used to treat moderate or severe postoperative pain.

There was insufficient information of adequate quality for any safety analyses to be conducted. Dipyrone has been reported to cause blood dyscrasias such as agranulocytosis (an adverse effect which can occur with short‐term treatment). There was no mention of blood dyscrasias, or any other serious adverse event in these trials.

Further evidence is required to determine whether the potential benefits of using dipyrone outweigh its potential harm. In many countries other drugs for which more evidence exists are readily available, and should probably be used in preference to dipyrone. In other countries, dipyrone may be one of a handful of drugs available. While dipyrone may provide adequate analgesia, patients should be monitored for blood dyscrasias as recommended by the manufacturers, if resources allow. The short onset of agranulocytosis seen in case reports is cause for concern. Both this, and the need for monitoring, have implications for over the counter availability.

Methodologically rigorous studies would be required to establish the benefit/risk trade‐off for dipyrone, particularly if the risk of rare adverse events was to be established. Such studies would need to be large, of adequate duration, provide definitions of outcomes and independent verification of cases.

Feedback

Availability of dipyrone in South Africa

Summary

What trade names are used for 'Dipyrone' in South Africa and which companies are distributing it? {SD: Should this be dated?}

Reply

We have referred to: Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference, 32nd Edition, Pharmaceutical Press, London which states that dipyrone is available in South Africa only as a combination drug (Hyoscine butylbromide/dipyrone).

The proprietary preparations are: Baralgan, Norifortan, Scopex Co (manufactured by Hoechst) Buscopan (manufactured by Boehringer Ingelheim)

Dipyrone is not listed on the World Health Organisation's 'Essential Drugs List'.

Contributors

Frances Fairman, Review Group Co‐ordinator

Acknowledgements

The following helped retrieve specific papers for the original review: Christine Aguilar; the Brazilian Cochrane Centre; Joan‐Ramon Laporte, University of Barcelona; Vladimir Stoukov, Centre for Evidence‐based Medicine, Moscow; Medical Information Unit, Aventis Pharma Ltd, UK; University Library Barquisimeto, University of Venezuela; Pablo Ortiz, Boehringer Ingelheim, Madrid; Luis Miguel Torres, Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar Cádiz, Spain.

Fuensanta Meseguer was an author on the original review but was not involved in the update of this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE (via OVID) search strategy

Dipyrone/

dipyrone OR metamizole.mp

adolkin OR afebrin OR aminopyrine sulphonate OR anador OR analgin OR analginum OR ascorfebrina OR baralgin OR dolemicin OR dolo buscopan OR huberdor OR inalgon OR lasain OR lisalgil OR metamizol OR metamizole OR metamizole sodium OR methampyrone OR minalgin OR natrium novaminsulfonicum OR neo meubrina OR neu novalgin OR neu novalgine OR neuro‐brachont OR neuro‐formatin S OR nolotil OR noramidaophenum OR noraminophenazonum OR norgesic OR novalgina OR novalgine OR novamidazofen OR optalgin OR pirenil OR sulpyrinepyrethane OR trisalgina.ti,ab

OR/1‐3

Pain, postoperative.sh

((postoperative adj4 pain$) or (post‐operative adj4 pain$) or post‐operative‐pain$ or (post$ NEAR pain$) or (postoperative adj4 analgesi$) or (post‐operative adj4 analgesi$) or ("post‐operative analgesi$")).ti,ab,kw.

((post‐surgical adj4 pain$) or ("post surgical" adj4 pain$) or (post‐surgery adj4 pain$)).ti,ab,kw.

(("pain‐relief after surg$") or ("pain following surg$") or ("pain control after")).ti,ab,kw.

(("post surg$" or post‐surg$) AND (pain$ or discomfort)).ti,ab,kw.

((pain$ adj4 "after surg$") or (pain$ adj4 "after operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ surg$")).ti,ab,kw.

((analgesi$ adj4 "after surg$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "after operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ surg$")).ti,ab,kw.

OR/5‐11

randomized controlled trial.pt.

controlled clinical trial.pt.

randomized.ab.

placebo.ab.

drug therapy.fs.

randomly.ab.

trial.ab.

groups.ab.

OR/13‐20

4 AND 12 AND 21

Appendix 2. EMBASE (via OVID) search strategy

Dipyrone/

dipyrone OR metamizole.mp

adolkin OR afebrin OR aminopyrine sulphonate OR anador OR analgin OR analginum OR ascorfebrina OR baralgin OR dolemicin OR dolo buscopan OR huberdor OR inalgon OR lasain OR lisalgil OR metamizol OR metamizole OR metamizole sodium OR methampyrone OR minalgin OR natrium novaminsulfonicum OR neo meubrina OR neu novalgin OR neu novalgine OR neuro‐brachont OR neuro‐formatin S OR nolotil OR noramidaophenum OR noraminophenazonum OR norgesic OR novalgina OR novalgine OR novamidazofen OR optalgin OR pirenil OR sulpyrinepyrethane OR trisalgina.ti,ab

OR/1‐3

Postoperative pain.sh

((postoperative adj4 pain$) or (post‐operative adj4 pain$) or post‐operative‐pain$ or (post$ NEAR pain$) or (postoperative adj4 analgesi$) or (post‐operative adj4 analgesi$) or ("post‐operative analgesi$")).ti,ab,kw.

((post‐surgical adj4 pain$) or ("post surgical" adj4 pain$) or (post‐surgery adj4 pain$)).ti,ab,kw.

(("pain‐relief after surg$") or ("pain following surg$") or ("pain control after")).ti,ab,kw.

(("post surg$" or post‐surg$) AND (pain$ or discomfort)).ti,ab,kw.

((pain$ adj4 "after surg$") or (pain$ adj4 "after operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ surg$")).ti,ab,kw.

((analgesi$ adj4 "after surg$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "after operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ surg$")).ti,ab,kw.

OR/5‐11

clinical trials.sh

controlled clinical trials.sh

randomized controlled trial.sh

double‐blind procedure.sh

(clin$ adj25 trial$).ab

((doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).ab

placebo$.ab

random$.ab

OR/13‐20

4 AND 12 AND 21

Appendix 3. CENTRAL search strategy

MESH descriptor Dipyrone

dipyrone OR metamizole:ti,ab,kw.

adolkin OR afebrin OR aminopyrine sulphonate OR anador OR analgin OR analginum OR ascorfebrina OR baralgin OR dolemicin OR dolo buscopan OR huberdor OR inalgon OR lasain OR lisalgil OR metamizol OR metamizole OR metamizole sodium OR methampyrone OR minalgin OR natrium novaminsulfonicum OR neo meubrina OR neu novalgin OR neu novalgine OR neuro‐brachont OR neuro‐formatin S OR nolotil OR noramidaophenum OR noraminophenazonum OR norgesic OR novalgina OR novalgine OR novamidazofen OR optalgin OR pirenil OR sulpyrinepyrethane OR trisalgina:ti,ab,kw.

OR/1‐3

MESH descriptor Pain, Postoperative

((postoperative adj4 pain$) or (post‐operative adj4 pain$) or post‐operative‐pain$ or (post$ NEAR pain$) or (postoperative adj4 analgesi$) or (post‐operative adj4 analgesi$) or ("post‐operative analgesi$")):ti,ab,kw.

((post‐surgical adj4 pain$) or ("post surgical" adj4 pain$) or (post‐surgery adj4 pain$)):ti,ab,kw.

(("pain‐relief after surg$") or ("pain following surg$") or ("pain control after")):ti,ab,kw.

(("post surg$" or post‐surg$) AND (pain$ or discomfort)):ti,ab,kw.

((pain$ adj4 "after surg$") or (pain$ adj4 "after operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ surg$")):ti,ab,kw.

((analgesi$ adj4 "after surg$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "after operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ surg$")):ti,ab,kw.

OR/4‐10

Limit 12 to CENTRAL

Appendix 4. Glossary

Categorical rating scale: The commonest is the five category scale (none, slight, moderate, good or lots, and complete). For analysis numbers are given to the verbal categories (for pain intensity, none = 0, mild = 1, moderate = 2 and severe = 3, and for relief none = 0, slight = 1, moderate = 2, good or lots = 3 and complete = 4). Data from different subjects is then combined to produce means (rarely medians) and measures of dispersion (usually standard errors of means). The validity of converting categories into numerical scores was checked by comparison with concurrent visual analogue scale measurements. Good correlation was found, especially between pain relief scales using cross‐modality matching techniques. Results are usually reported as continuous data, mean or median pain relief or intensity. Few studies present results as discrete data, giving the number of participants who report a certain level of pain intensity or relief at any given assessment point. The main advantages of the categorical scales are that they are quick and simple. The small number of descriptors may force the scorer to choose a particular category when none describes the pain satisfactorily. VAS: Visual analogue scale: For pain intensity, lines with left end labelled "no pain" and right end labelled "worst pain imaginable", and for pain relief lines with left end labelled "no relief of pain" and right end labelled "complete relief of pain", seem to overcome the limitation of forcing patient descriptors into particular categories. Patients mark the line at the point which corresponds to their pain or pain relief. The scores are obtained by measuring the distance between the no relief end and the patient's mark, usually in millimeters. The main advantages of VAS are that they are simple and quick to score, avoid imprecise descriptive terms and provide many points from which to choose. More concentration and coordination are needed, which can be difficult post‐operatively or with neurological disorders. TOTPAR: Total pain relief (TOTPAR) is calculated as the sum of pain relief scores over a period of time. If a patient had complete pain relief immediately after taking an analgesic, and maintained that level of pain relief for six hours, they would have a six‐hour TOTPAR of the maximum of 24. Differences between pain relief values at the start and end of a measurement period are dealt with by the trapezoidal rule. This is a simple method that approximately calculates the definite integral of the area under the pain relief curve by calculating the sum of the areas of several trapezoids that together closely approximate to the area under the curve. SPID: Summed pain intensity difference (SPID) is calculated as the sum of the differences between the pain scores and baseline pain score over a period of time. Differences between pain intensity values at the start and end of a measurement period are dealt with by the trapezoidal rule. VAS TOTPAR and VAS SPID are visual analogue versions of TOTPAR and SPID. See "Measuring pain" in Bandolier's Little Book of Pain, Oxford University Press, Oxford. 2003; pp 7‐13 (Moore 2003).

Appendix 5. Summary of efficacy outcomes in individual studies

| Analgesia | Rescue medication | ||||

| Study ID | Treatment | PI or PR | Number with 50% PR | Median time to use (h) | Number using |

| Bagan 1998 | (1) dipyrone 575 mg, n = 40 (2) dexketoprofen 12.5 mg, n = 38 (3) dexketoprofen 25 mg, n = 42 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 8.5 (2) 10.7 (3) 13.0 |

(1) 14/40 (2) 18/38 (3) 25/42 |

All >6 h | at 6 h: (1) 19/40 (2) 12/38 (3) 11/42 |

| Bhounsule 1990 | (1) dipyrone 500 mg, n = 20 (2) ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 20 (3) paracetamol 600 mg, n = 20 (4) aspirin 600 mg, n = 20 (5) placebo, n = 20 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 13.0 (2) 14.2 (3) 8.1 (4) 6.7 (5) 7.4 |

(1) 12/20 (2) 13/20 (3) 7/20 (4) 5/20 (5) 6/20 |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Boraks 1987 | (1) dipyrone 500 mg, n = 39 (2) aspirin 650 mg, n = 41 (3) flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 40 (4) placebo, n = 39 |

At 6 h: (1) 28/39 (2) 25/41 (3) 25/40 (4) 16/39 |

Not reported | at 6 h: (1) 6/39 (2) 1/41 (3) 4/40 (4) 20/39 |

|

| Gonzalez Gracia 1994 | (1) dipyrone 500 mg, n = 30 (2) ketorolac 10 mg, n = 30 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 13.8 (2) 15.1 |

(1) 19/30 (2) 22/30 |

Not reported | at 6 h: (1) 14/30 (2) 11/30 |

| Ibarra 1993 | (1) dipyrone 2.5 g, n = 48 (2) ketorolac 30 mg, n = 49 |

PGE: v good or excellent at 6 h: (1) 37/48 (2) 36/49 |

Not reported | at 6 h: (1) 4/48 (2) 3/49 |

|

| Mendl 1992 | (1) dipyrone 2.5 g iv, n = 50 (2) tramadol 100 mg iv, n = 50 |

VAS TOTPAR 4: (1) 302.3 (2) 280.0 |

(1) 39/50 (2) 36/50 |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Miguel Rivero 1997 | (1) dipyrone 2 g, n = 35 (2) ibuprofen arginine 400 mg, n = 36 (3) placebo, n = 35 |

VAS SPID 5: (1) 196.8 (2) 187.0 (3) 119.8 |

(1) 26/35 (2) 25/36 (3) 16/35 |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Olson 1999 | (1) dipyrone 500 mg, n = 27 (2) ketoprofen 25 mg, n = 28 (3) ketoprofen 50 mg, n = 26 (4) placebo, n = 27 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 9.6 (2) 9.1 (3) 9.3 (4) 2.8 |

(1) 19/27 (2) 19/28 (3) 18/26 (4) 5/27 |

(1) >6 (2) >6 (3) >6 (4) 1.3 |

at 6 h: (1) 14/67 (2) 20/67 (3) 25/66 (4) 31/39 |

| Patel 1980 | (1) dipyrone 2.5 g im, n = 51 (2) pethidine 100 mg im, n = 49 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 15.1 (2) 15.5 |

(1) 37/51 (2) 36/49 |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Pinto 1984 | (1) dipyrone 500 mg, n = 27 (2) paracetamol 500 mg, n = 29 (3) placebo, n = 29 |

TOTPAR 4: (1) 10.7 (2) 11.4 (3) 5.6 |

(1) 21/27 (2) 24/29 (3) 10/27 |

Not reported | at 4 h: (1) 2/27 (2) 0/29 (3) 8/29 |

| Rosas Perez 1986 | (1) dipyrone 1 g supp, n = 20 (2) suprofen 300 mg supp, n = 20 |

VAS SPID 6: (1) 295.8 (2) 267.7 |

(1) 17/20 (2) 15/20 |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Rubinstein 1986 | (1) dipyrone 1000 mg, n = 30 (2) paracetamol 500 mg, n = 30 (3) placebo, n = 30 |

TOTPAR 4: (1) 11.9 (2) 10.1 (3) 4.7 |

(1) 26/30 (2) 22/30 (3) 8/30 |

Not reported | at 4 h: (1) 0/30 (2) 2/30 (3) 6/30 |

| Sakata 1986 | (1) dipyrone 1000 mg, n = 29 (2) paracetamol 1000 mg, n = 30 (3) placebo, n = 27 |

TOTPAR 4: (1) 8.7 (2) 8.4 (3) 2.8 |

(1) 18/29 (2) 17/30 (3) 3/27 |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Santos Pereira 1986 | (1) dipyrone 1000 mg, n = 28 (2) paracetamol 1000 mg, n = 28 (3) placebo, n = 29 |

SPID 4: (1) 6.2 (2) 6.4 (3) 2.1 |

(1) 22/28 (2) 21/28 (3) 7/29 |

Not reported | at 4 h: (1) 1/28 (2) 0/28 (3) 11/29 |

| Stankov 1995 | (1) dipyrone 2.5 g, n = 51 (2) tramadol 100 mg, n = 49 |

VAS SPID 4: (1) 247.8 (2) 228.0 |

(1) 32/51 (2) 28/49 |

Not reported | at 4 h: (1) 1/51 (2) 0/49 |

Appendix 6. Summary of adverse events and withdrawals

| Adverse events | Withdrawals | ||||

| Study ID | Treatment | Any | Serious | Adverse event | Other |

| Bagan 1998 | (1) dipyrone 575 mg, n = 40 (2) dexketoprofen 12.5 mg, n = 38 (3) dexketoprofen 25 mg, n = 42 |

13 participants in total reported 18 events (1) somnolence, headache (2) somnolence, gastric discomfort, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, tiredness, other |

None | None | None |

| Bhounsule 1990 | (1) dipyrone 500 mg, n = 20 (2) ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 20 (3) paracetamol 600 mg, n = 20 (4) aspirin 600 mg, n = 20 (5) placebo, n = 20 |

None | None | None | Not reported |

| Boraks 1987 | (1) dipyrone 500 mg, n = 39 (2) aspirin 650 mg, n = 41 (3) flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 40 (4) placebo, n = 39 |

(1) 4/39 (somnolence, dizziness, nausea, headache) (2) 6/41 (3) 7/40 (4) 8/39 (somnolence, dizziness, nausea, warm feeling) |

Not reported | None reported | Not reported |

| Gonzalez Garcia 1994 | (1) dipyrone 500 mg, n = 30 (2) ketorolac 10 mg, n = 30 |

(2) 2/30 (somnolence) | None | None | None |

| Ibarra 1993 | (1) dipyrone 2.5 g, n = 48 (2) ketorolac 30 mg, n = 49 |

(1) 1/48 (nausea) (2) 4/49 (nausea, tiredness, headache) (mild or moderate, related to test drugs) |

None | None | None |

| Mendl 1992 | (1) dipyrone 2.5 g iv, n = 50 (2) tramadol 100 mg iv, n = 50 |

"No clinically relevant side effects observed" | None | None | Not reported |

| Miguel Rivero 1997 | (1) dipyrone 2 g, n = 35 (2) ibuprofen arginine 400 mg, n = 36 (3) placebo, n = 35 |

(1) 0/35 (2) 1/36 (3) 1/35 (headache ‐ judged related to test drug) |

None | None | None |

| Olson 1999 | (1) dipyrone 500 mg, n = 27 (2) ketoprofen 25 mg, n = 28 (3) ketoprofen 50 mg, n = 26 (4) placebo, n = 27 |

"No adverse events reported during this study" | None | None | None |

| Patel 1980 | (1) dipyrone 2.5 g im, n = 51 (2) pethidine 100 mg im, n = 49 |

(1) 1/51 (hypotension) (2) 1/49 (urinary retention) (not related to test drugs) |

None | None | Not reported |

| Pinto 1984 | (1) dipyrone 500 mg, n = 27 (2) paracetamol 500 mg, n = 29 (3) placebo, n = 29 |

(1) 1/27 (arterial hypertension) | None | None | Not reported |

| Rosas Perez 1986 | (1) dipyrone 1 g supp, n = 20 (2) suprofen 300 mg supp, n = 20 |

"No undesirable side effects attributable to the product were observed" | None | None | Not reported |

| Rubinstein 1986 | (1) dipyrone 1000 mg, n = 30 (2) paracetamol 500 mg, n = 30 (3) placebo, n = 30 |

(2) 1/30 (vomiting) | None | None | None |

| Sakata 1986 | (1) dipyrone 1000 mg, n = 29 (2) paracetamol 1000 mg, n = 30 (3) placebo, n = 27 |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Santos Pereira 1986 | (1) dipyrone 1000 mg, n = 28 (2) paracetamol 1000 mg, n = 28 (3) placebo, n = 29 |

"well tolerated" | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Stankov 1995 | (1) dipyrone 2.5 g, n = 51 (2) tramadol 100 mg, n = 49 |

(1) 12/51 (2) 16/4 (mostly gastrointestinal with nausea, or affecting airways in participants with bronchitis) |

Not reported | None | None |

Appendix 7. Abstract and Plain language summary in Spanish

Antecedentes: La dipirona (metamizol) es un fármaco antiinflamatorio no esteroideo utilizado en algunos países para tratar el dolor (postquirúrgico, cólico, oncológico, y de migraña). En otros paises no está autorizado debido al riesgo de producir agranulocitosis grave.

Objetivos: Valorar la eficacia y seguridad de dipirona en dosis única en dolor agudo postquirúrgico.

Estrategia de búsqueda: En la revisión inicial, se utilizaron las bases de datos CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, LILACS, y la Base de Datos de la Unidad del Dolor de Oxford, hasta diciembre de 1999. Para la revisión actualizada se buscó en CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE y LILACS, hasta febrero de 2010.

Criterios de Selección: Ensayos clínicos controlados, aleatorizados y doble ciego de dipirona en dosis œnica, con control activo o frente a placebo, en el tratamiento del dolor postquirúrgico moderado o severo de pacientes adultos. Se incluyeron ensayos en los que la administración de los fármacos en estudio fuese oral, rectal, intramuscular o intravenosa.

Recogida de datos y análisis: Se valoró la calidad metodológica de los estudios y se extrajeron los datos de los mismos por dos autores de forma independiente. Se utilizó la suma del alivio total del dolor en 6 horas (TOTPAR) para calcular el número de pacientes que obtenían al menos el 50% del alivio del dolor, sobre la valoración basal. Los resultados obtenidos se utilizaron para calcular, con los intervalos de confianza del 95%, el beneficio relativo comparado con placebo, y el número necesario de pacientes que deberían ser tratados para obtener al menos un alivio del dolor del 50% en uno de ellos (NNT). Las medidas adicionales de eficacia incluyeron la utilización de medicación de rescate y el momento de su administración. Se recogió información sobre efectos adversos y retiradas de participantes.

Principales resultados: Se incluyeron quince estudios, en los cuales 173 participantes recibieron 500 mg de dipirona por vía oral, 101 participantes 2.5 g de dipirona por vía intravenosa, 99 participantes 2.5 g de dipirona por vía intramuscular, y menos de 60 participantes recibieron otras dosis. Todos los estudios tuvieron control activo (ibuprofeno, paracetamol, aspirina, flurbiprofeno, ketoprofeno, dexketoprofeno, ketorolaco, petidina, tramadol, suprofeno), y ocho estudios estuvieron controlados con placebo. En cinco estudios (288 participantes) el porcentaje de pacientes que obtuvo al menos el 50% de alivio en 4 a 6 horas con 500 mg de dipirona oral fue del 70% mientras que con placebo el porcentaje que lo obtuvo fue del 30% (NNT 2.4 (1.9‐3.2)). En cuatro estudios (248 participantes), el número de pacientes que precisó medicación de rescate fue menor con dipirona (7%) que con placebo (34%). En dos estudios (200 participantes), no se observaron diferencias en el número de pacientes que obtenían al menos el 50% de alivio con 2.5 g de dipirona intravenosa (70%) y con 100 mg de tramadol intravenoso (65%). No se notificaron efectos adversos graves.

Conclusiones de los autores: En base a información muy limitada, la dosis única de 500 mg de dipirona proporciona un buen alivio del dolor en el 70% de los pacientes. De cada cinco pacientes que reciben 500 mg, en dos se obtendría este alivio que no se hubiese obtenido con placebo, y además el número de pacientes que necesitaría medicación de rescate habría sido menor.

Resumen en lenguaje común

La dipirona (metamizol) es un analgésico popular en muchos países que se utiliza para el tratamiento del dolor postquirúrgico, el dolor cólico, el dolor oncológico y la migraña. En otros países, como EEUU, Reino Unido y Japón), no està autorizado su uso por la posibilidad de que produzca alteraciones sanguíneas graves, tales como agranulocitosis. La información obtenida en los estudios revisados ha sido escasa para extraer conclusiones acerca de la mayoría de las dosis y vías de admisnistración de dipirona utilizadas. La administración de una dosis única de 500 mg de dipirona proporcionó al menos un 50% de alivio del dolor postquirúrgico moderado o severo en pacientes adultos, y su eficacia fue similar a la de 400 mg de ibuprofeno. La dosis única de 2.5 g intravenosos fue equivalente a 100 mg de tramadol intravenoso para obtener un alivio de al menos el 50%. La información a cerca de efectos adversos fue escasa, pero no se notificaron efectos adversos graves o retiradas por éstos.

Appendix 8. Search terms used for earlier review

dipyrone OR (all brand names of dipyrone) AND (pain or analgesi*) The brand names used in the search strategy were: adolkin, afebrin, aminopyrine sulphonate, analgin, analginum, ascorfebrina, baralgin, dolemicin, dolo buscopan, huberdor, inalgon, lasain, metamizol, metamizole, metamizole sodium, methampyrone, natrium novamin‐sulfonicum, minalgin, neo meubrina, neu novalgin, neu novalgine, neuro‐brachont, neuro‐formatin S, nolotil, noramidaophenum, noraminophenazonum, norgesic, novalgina, novalgine, novamidazofen, optalgin, pirenil, pyrethane, sulpyrine, trisalgina (Reynolds 1993).

Data and analyses

Comparison 1.

Dipyrone 500 mg versus placebo

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Patients with ≥50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours | 5 | 288 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.39 [1.84, 3.11] |

| 2 Participants using rescue medication over 4 to 6 hours | 4 | 248 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.21 [0.11, 0.40] |

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Dipyrone 500 mg versus placebo, Outcome 1 Patients with ≥50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

Comparison 2.

Dipyrone 2.5 g versus tramadol 100 mg (intravenous)

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Patients with ≥50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours | 2 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.90, 1.32] |

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 March 2014 | Amended | This review will be replaced by a new protocol in preparation. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2001 Review first published: Issue 3, 2001

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 25 November 2013 | Amended | This review has been withdrawn, seePublished notes. |

| 5 April 2011 | Amended | Byline altered; Fuensanta Meseguer added to acknowledgements as was not involved in the update of this review. |

| 8 February 2011 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 10 November 2010 | Review declared as stable | The authors declare that there is unlikely to be any further studies to be included in this review and so it should be published as a 'stable review'. |

| 24 September 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 20 July 2010 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Data on use of rescue medication in original studies added to analyses. Review rewritten to conform with new Cochrane standards and methods. |

| 11 March 2010 | New search has been performed | New searches run. No new studies identified for inclusion. |

| 28 May 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 23 May 2003 | Feedback has been incorporated | Feedback incorporated |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, active control (dexketoprofen), single and multiple oral dose. Study duration 6 h for single dose phase and 3 days for multiple dose phase. Baseline PI = moderate or severe Self assessment at t = 0, 0.15, 0.30, 1, then hourly up to 6 h for single dose phase. |

|

| Participants | Impacted third molar extraction N = 120 M 46, F 74 Mean age 25 years |

|

| Interventions | Dipyrone 575 mg, n = 40 Dexketoprofen‐trometamol 12.5 mg, n = 38 Dexketoprofen‐trometamol 25 mg, n = 42 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale (0‐3) and 100mm VAS (no pain to maximum pain) PR: standard 5 point scale (0‐4) PGE: non‐standard 4 point scale Use of rescue medication Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4 Rescue medication allowed after 1 h |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "identical capsules" |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, placebo control, single oral dose. Study duration 6 h. Baseline PI = severe Self assessment at t = 0, 0.5,1.5, 2, then hourly up to 6 h. |

|

| Participants | Post‐episiotomy N = 100 All F Age: Not reported |

|

| Interventions | Dipyrone 500 mg, n = 20 Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 20 Paracetamol 600 mg, n = 20 Aspirin 600 mg, n = 20 Placebo, n = 20 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale (0‐3) PR: non‐standard 4 point PR (1‐4) ‐ standard wording, but nonstandard numbering Adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W0. Total = 2 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | "All tablets pre‐packaged in individual dose packets" |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, placebo control, single oral dose. Study duration 6 h. Baseline PI = moderate or severe Self assessment at t = 0, 0.5, 1, then hourly up to 6 h. |

|

| Participants | Dental extraction N = 159 M 84, F 75 Mean age: 27 years |

|

| Interventions | Dipyrone 500 mg, n = 39 Aspirin 650 mg, n = 31 Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 40 Placebo, n = 39 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale (0‐3) PR: 5 point scale (1‐5) standard wording, but nonstandard numbering PGE: standard 5 point scale Adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W0. Total = 2 Rescue medication allowed after 1 h |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, active (ketorolac) control, single oral dose. Study duration 6 h. Baseline PI = moderate or severe Self assessment at t = 0, 0.5, 1.0, then hourly up to 6 h. |

|

| Participants | Orthopaedic surgery N = 60 M 27, F 33 Mean age = 41 years |

|

| Interventions | Dipyrone, 500 mg, n = 30 Ketorolac 10 mg, n = 30 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: non standard 5 point scale (none‐very severe) PR: standard 5 point scale (0‐4) Use of rescue medication Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W1. Total = 3 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, active control (ketorolac), single IM dose. Study duration 6 h Baseline PI = moderate or severe Self assessment at t = 0, 0.5, 1.0, then hourly up to 6 h. |

|

| Participants | Orthopaedic surgery N = 97 M 40, F 57 Mean age = 35 years |

|

| Interventions | Dipyrone 2.5 g IM, n = 48 Ketorolac 30 mg IM, n = 49 (48 analysed for efficacy) |

|

| Outcomes | PI: non‐standard 5 point scale (none‐very severe) PR: standard 5 point scale (0‐4) PGE: standard 5 point scale |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W1. Total = 3 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | "dual observer technique" |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, active control (tramadol), single IV dose. Study duration 4 h Baseline PI = severe Self assessment at t = 0.15, 0.30, 1, then hourly up to 4 h. |

|

| Participants | Abdominal or urinary tract surgery N = 100 M/F not reported Age 18‐65 years |

|

| Interventions | Dipyrone 2.5 g IV, n = 50 Tramadol 100 mg IV, n = 50 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: VAS ‐ verbal pain rating scale (undefined) PR: 100 mm VAS (no relief‐complete relief) Adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W0. Total = 2 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, placebo control, single and multiple oral dose phases. Duration of single dose phase 5 h. Baseline PI = ≥50/100 mm Self assessment at t = 0, 0.15, 0.30, 1, then hourly up to 5 h. |

|

| Participants | Orthopaedic surgery ‐ total hip replacement N = 106 M 48, F 58 Mean age 62 years |

|

| Interventions | Dipyrone 2 g IM, n = 35 Ibuprofen arginine 400 mg (oral), n = 36 Placebo, n = 35 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: 100 mm VAS (no pain‐unbearable pain) PGE: standard 5 point scale Use of rescue medication Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4 Rescue medication allowed after 1 h |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "double dummy" |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, placebo control, single oral dose. Study duration 6 h Baseline PI = severe Self assessment at t = 0.15, 0.30, 1.0, 1.5 and then hourly up to 6 h. |

|

| Participants | Post‐episiotomy or 2nd degree vaginal tear N = 108 All F Mean age: 24 years |

|

| Interventions | Dipyrone 500 mg, n = 27 Ketoprofen 25 mg, n = 28 Ketoprofen 50 mg, n = 26 Placebo, n = 27 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale (0‐3) PR: standard 5 point scale (0‐4) PGE: non‐standard 4 point scale Use of rescue medication Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W1. Total = 4 Remedication was allowed after 1 h |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "individual randomisation envelope for each patient entering the study " |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Study medication not identical, but nurse prepared medication as indicated to total volume of 4 ml and administered it to the patient. Administration of study medication and observation of patient carried out by two individuals to maintain the double‐blind character. |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, active (pethidine) control, single IM dose. Study duration 6 h. Baseline PI = severe Self assessment at t = 0.30, 1, then hourly up to 6 h. |

|

| Participants | Elective exploratory laparotomy N = 100 M 82, F 18 Mean age 40 years |

|

| Interventions | Dipyrone 2.5 g IM, n = 51 Pethidine 100 mg IM, n = 49 |

|

| Outcomes | PR: standard 5 point scale (0‐4) Adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W0. Total = 2 Rescue medication allowed after 1 h |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Study medication not indistinguishable, but administered by research worker who had no contact with other investigators |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, placebo control, single oral dose. Study duration 4 h Baseline PI = moderate or severe Self assessment at t = 0.15, 1, then hourly up to 4 h. |

|

| Participants | Orthopaedic surgery N = 85 M 57, F 28 Mean age 39 years |

|

| Interventions | Dipyrone 1 g, n = 28 Acetaminophen 1 g, n = 28 Placebo, n = 29 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale (0‐3) PR: standard 5 point scale (0‐4) PGE: non‐standard 4 point scale Use of rescue medication |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W0. Total = 3 Rescue medication allowed after 2 h |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Capsules were identical in appearance |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, placebo control, single oral dose. Study duration 4 h. Baseline PI = moderate or severe Self assessment at t = 0.5, 1, and then hourly up to 4 h. |

|

| Participants | Post‐tonsillectomy N = 85 M 33, F 52 Mean age: 23 years |

|

| Interventions | Dipyrone 500 mg, n = 27 Acetaminophen 500 mg, n = 29 Placebo, n = 29 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale (0‐3) PR: standard 5 point scale (0‐4) PGE: non‐standard 4 point scale Use of rescue medication Adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W0. Total = 3 Rescue medication allowed after 2 h |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Capsules were identical in appearance |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, active control (suprofen), single rectal dose. Study duration 6 h. Baseline PI = moderate or severe Self assessment at t = 0.5, 1, and then hourly up to 6 h. |

|

| Participants | Post‐episiotomy N = 40 All F Mean age: 26 years |

|

| Interventions | Dipyrone 1 g suppository, n = 20 Suprofen 300 mg suppository, n = 20 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: 10 cm VAS (no pain‐maximum pain) PR: standard 5 point scale (0‐4) where [0 = none, 2 = 50% PR, 3 = 75% PR, 4 =100% PR] PGE: non‐standard 4 point scale Use of rescue medication Adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W0. Total = 2 Rescue medication allowed after 1 h |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, placebo control, single oral dose. Study duration 4 h Baseline PI = moderate and severe Self assessment at t = 0.30, 1, and then hourly up to 4 h. |

|

| Participants | Urological surgery N = 90 Mean age 49 years |

|

| Interventions | Dipyrone 500 mg, n = 30 Acetaminophen 500 mg, n = 30 Placebo, n = 30 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale (0‐3) PR: standard 5 point scale (0‐4) PGE: non‐standard 4 point scale Use of rescue medication Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4 Rescue medication allowed after 2 h |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Capsules were identical in appearance |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, placebo control, single oral dose. Study duration 4 h Baseline PI = moderate and severe Self assessment at t = 0.30, 1, and then hourly up to 4 h. |

|

| Participants | Mainly orthopaedic surgery N = 86 M 49, F 37 Mean age: 32 years |

|

| Interventions | Dipyrone 1 g, n = 30 Acetaminophen 1 g, n = 30 Placebo group, n = 30 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale (0‐3) PR: standard 5 point (0‐4) PGE: nonstandard 4 point scale |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W0. Total = 2 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, placebo control, single oral dose. Duration of study 4 h Baseline PI = moderate and severe Self assessment at t = 0.15, 0.30, 1, 2 h and 4 h. |

|

| Participants | Elective abdominal or urological surgery N = 100 (88 analysed ‐ 12 did not fulfil eligibility criteria) M 47, F 53 Mean age 49 years |

|

| Interventions | Dipyrone 2.5 g, n = 51 (44 analysed) Tramadol 100 mg, n = 49 (44 analysed) |

|

| Outcomes | PI: 100 mm VAS (no pain‐worst possible pain) PR: 100 mm VAS (no PR‐complete PR) PGE: 100 mm VAS (ineffective‐excellent) Use of rescue medication Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W1. Total = 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "randomisation list" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Study drug administered by one investigator and assessed in the presence of another who was unaware of the allocation |

DB ‐ double blind; F ‐ female; M ‐ male; N ‐ total number of participants in study; n ‐ number of participants in treatment arm; PGE ‐ patient global evaluation; PI ‐ pain intensity; PR ‐ pain relief; R ‐ randomised; W ‐ withdrawals

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Aizawa 1972 | Not randomised. |

| Alvarez Rios 1994 | Dipyrone administered as rescue analgesic only. |

| Amata 1997 | Not randomised. |

| Atalay 1995 | Comparators both used extradural route. |

| Banos 1989 | Not a randomised controlled trial ‐ review. |