Abstract

Discoveries of bacterial communities in environments that previously have been described as sterile have in recent years radically challenged the view of these environments. In this study we aimed to use 16S rRNA sequencing to describe the composition and temporal stability of the bacterial microbiota in bovine milk from healthy udder quarters, an environment previously believed to be sterile. Sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene is a technique commonly used to describe bacterial composition and diversity in various environments. With the increased use of 16S rRNA gene sequencing, awareness of methodological pitfalls such as biases and contamination has increased although not in equal amount. Evaluation of the composition and temporal stability of the microbiota in 288 milk samples was largely hampered by background contamination, despite careful and aseptic sample processing. Sequencing of no template control samples, positive control samples, with defined levels of bacteria, and 288 milk samples with various levels of bacterial growth, revealed that the data was influenced by contaminating taxa, primarily Methylobacterium. We observed an increasing impact of contamination with decreasing microbial biomass where the contaminating taxa became dominant in samples with less than 104 bacterial cells per mL. By applying a contamination filtration on the sequence data, the amount of sequences was substantially reduced but only a minor impact on number of identified taxa and by culture known endogenous taxa was observed. This suggests that data filtration can be useful for identifying biologically relevant associations in milk microbiota data.

Introduction

The introduction of DNA based methods to study bacterial communities has in recent years stimulated interest and substantially challenged previous knowledge about environments thought to be sterile. Milk, placenta and airways are examples of environments that previously were considered sterile in healthy individuals, but when studied with DNA based methods revealed to harbor their own microbiome [1–5]. Simultaneously publications on problems with laboratory and reagent contamination in microbiota studies have become increasingly common and a list of commonly occurring contaminating genera has been created [6, 7]. Occasionally discoveries of a microbiome in a previously believed sterile environments have been questioned and attributed to methodological artefacts [8].

Milk microbiota has been suggested to play an important role for infant gut development and maternal mammary gland health [9]. For the bovine mammary gland, a milk microbiota has been described [1] and associated to; somatic cell count (SCC) [10], culture negative mastitis samples [2], intra-mammary infection [11, 12],history of intra-mammary infection [13], farm environment [14] and cow genotype [15]. Recently the “logical implications” for a bovine milk microbiota has been questioned based on udder immunology and established models for mastitis control [16].

Sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene is the most commonly used technique to describe bacterial composition and diversity in various environments. 16S rRNA gene sequencing has revolutionized science but it is a challenging technique that is prone to introduction of errors and biases (see Pollock et al. [17] for review). Several published studies report occurrence of contamination in blank controls originating either from the reagents used to process samples or the laboratory environment [6–8, 18, 19]. Salter et al. [6] was among the first to suggest a correlation between microbial biomass and level of contamination. In their study, dilution series of a pure culture of Salmonella bongori became dominated with non-Salmonella DNA after extraction and sequencing when input bacterial biomass was approximately 103–104 bacterial cells per mL. Glassing et al.[7] found similar results, in their study they extracted DNA from molecular grade water and determined DNA concentration using qPCR and universal primers. They reported contamination as 10 Escherichia coli equivalent genomes per μl in the absence of competing human DNA, corresponding to 104 E. coli cells/mL. Subsequently, the “best practice” for microbiome studies based on sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene is constantly discussed [17].

In this paper we add information to the knowledge gap on how the microbiome profile in low biomass bovine milk samples is affected by sample processing.

The milk samples used in this study came from an animal experiment that was designed to assess the composition and temporal stability of the bovine milk microbiota in healthy udder quarters using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Due to earlier reported technical challenges with samples containing a low bacterial biomass [6, 7] we sequenced the collected milk samples, negative controls, positive controls and used culturing data to evaluate; 1) how sample preparation and sequencing influence the bacterial composition, 2) the relation between cultivable bacteria and microbiota composition assessed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing and 3) level of contamination. Further we assessed two data filtration methods to exclude contaminating taxa from the data set.

Material and method

Animal study design

Nine cows in the dairy herd at the Swedish Livestock Research Center in Uppsala, Sweden were enrolled in the experiment. The cows were in lactation 1–3, day 187–316 in lactation at first sampling and had a milk SCC below 100 000 cells/mL in each udder quarter for six samplings during the three weeks prior to the start of the experiment. Milk SCC is used as a measurement of inflammation in the mammary gland and can also be used as an indicator of intramammary infection. SCC below 100 000 cells per mL is considered to indicate a healthy mammary gland. Quarter level milk samples were taken before morning milking on Mondays and Thursdays over four consecutive weeks. All cows were fed a standard diet with ad libitum silage and individual concentrate rations to meet the calculated nutrient requirements for their individual milk production. During the whole experiment all cows were kept in one group in a loose housing system, having access to the same type of bedding material, milked twice daily in an automatic rotary (DeLaval AMR, DeLaval AB, Tumba, Sweden) with 12 hour intervals. No antibiotics or other medication were given to the animals during the experiment or the three weeks preceding the experiment.

All animal handling was approved by the Uppsala animal ethics committee, protocol no: C99/13.

Sampling and bacterial culturing

Milk samples were taken according to guidelines for bacteriological analyses [20]. Teats were wiped visually clean with an individual moist cloth, the teat apex was wiped with two alcohol soaked cotton wads, three squirts of milk were discarded before the milk sample was collected by hand milking into a sterile 15 mL tube and placed on ice. The collected milk samples were transported to a laboratory and gently mixed after reaching room temperature before being divided into five aliquots, each consisting of 2 mL of milk; four aliquots were frozen at minus 80°C and stored (for maximum 7 months) until sample preparation whereas the fifth aliquot was used for bacterial culturing and determination of SCC. The maximum time from sampling to freezing or bacterial culturing was 4.1 and 5.1 hours, respectively.

For bacterial culturing; 10 μl of milk was inoculated on agar plates with 5% bovine blood and 0.05% esculin (National Veterinary Institute, Uppsala, Sweden) and incubated aerobically at 37°C. Growth was evaluated after 24 and 48 hours as no growth 0–2 CFU/10 μl, sparse growth 3–10 CFU/10 μl, moderate growth 11–50 CFU/10 μl or abundant growth >50 CFU/10 μl. Plates with growth of >2 CFU were evaluated, and bacterial isolates were identified to species level using MALDI-TOF, when appropriate, at the ISO 17025 accredited Mastitis Laboratory at the National Veterinary Institute, Uppsala, Sweden. Milk SCC was measured on a DeLaval Cell counter (DCC DeLaval AB, Tumba, Sweden) with a fluorescent microscopy based method. Milk aliquots were processed and bacterial inoculation was performed on an ethanol cleaned bench top, only sterile equipment was used in contact with milk.

DNA extraction

Milk aliquots were thawed, warmed to 20°C and vortexed at room temperature before 1 mL of milk was withdrawn for DNA extraction. The milk was centrifuged at 13 000 x g for 5 minutes, the supernatant and the fat layer was removed and DNA was extracted from the cell pellet using the PowerFood Microbial DNA isolation kit, kit batch no PF15C12, (MO BIO Laboratories, Inc., Carlsbad, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions except that a Mini-Beadbeater (Biospec products, Bartlesville, USA) was used for cell lysis. The bead beating step was performed 2 x 1 minutes at the setting homogenize. DNA extraction was performed in batches of 24 samples. For each DNA extraction batch an empty vial was used as a no-template DNA extraction control (NTC) into which the first reagent was added and further processed as the milk samples, i.e. one NTC per 23 extracted milk samples.

16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing

Illumina MiSeq sequencing libraries were prepared by amplifying the V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene using the 341F-805R primers described by Hugerth et al. [21]. The primers contained a linker sequence compatible with barcoding primers that were used to attach sample specific barcodes and Illumina adaptors in a second PCR. Each PCR reaction contained 12.5 μl of Phusion high-fidelity PCR master mix with HF buffer (Life technologies; Carlsbad, USA), 1.25 μl of each primer in a 10 μM solution, 5 μl DNA free water and 5 μl of DNA template. Thermocycling was performed on a MyCycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, USA) and thermocycling conditions were: initial denaturation at 98°C for 30 sec, 35 cycles of denaturation at 98°C for 10 sec, annealing at 60°C for 30 sec and elongation at 72°C for 7 sec, a final elongation was performed at 72°C for 2 min after the last cycle. A positive and a negative PCR control were included in each run and the PCR reaction was repeated if the negative PCR control contained a band when visualised on 1% agarose gel. PCR products (20 μl) were purified with Ampure Beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, USA) using 0.8 volumes of beads per volume of PCR product and eluted in (40 μl of) DNA free water. The second PCR attached Illumina adapters and barcodes; used the same thermocycling conditions for 10 cycles, 10 μl of purified PCR products as DNA template and one barcode per milk sample. PCR products were again purified with Ampure Beads but eluted in Elution Buffer. DNA was quantified with Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA). The samples were thereafter pooled into equimolar amounts and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq sequencer with v3 sequencing chemistry (Illumina Inc., San Diego, USA) at the Science for Life Laboratory (Uppsala, Sweden). The NTC’s from DNA extraction were included in all the steps of the 16S gene amplification. In the second PCR, all NTC reactions were run separately but a limited number of barcodes were used, i.e. the same barcode was used for several NTC. DNA extraction and first PCR preparations were performed in a laminar air-flow hood cleaned with 10% bleach and 70% ethanol, and UV-irradiated for 30 minutes before execution of sample processing.

Mock community as positive control

Five commonly occurring udder pathogens were chosen to create a bacterial mock community used for method evaluation. Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883, Streptococcus dysgalactiae CCUG 39323, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 and Trueperella pyogenes CCUG 39326 were cultured separately in 50 mL nutrient broth with 10% horse serum aerobically on a shaker at 37°C. The time of culture was 25 hours for T. pyogenes and 4 hours for the other bacteria. Bacterial concentrations were determined by manual counting of several aliquots from different dilutions using a Bürker counting chamber and a microscope with 100X enlargement. The five bacterial strains were used to create a mock community with equal numbers of cells and the mock community was prepared in three different dilutions (107, 105 and 103 cells of each bacterial species per mL). DNA from the mock communities was extracted and 16S gene amplification was performed as for the milk samples except that a Precellys24 (Bertin Technologies, Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France, with cell disruption for 2 x 45 sec at 6500 rpm) was used for cell lysis during DNA extraction. Information on number of 16S rRNA gene copies per bacterial strain was obtained from the Ribosomal RNA Operon Copy Number Database (RRNDB) and NCBI GeneBank for accurate calculation of relative abundance of 16S rRNA genes in input data.

Illumina sequencing data analysis

The generated sequencing data was processed according to the procedure described by Müller et al. [22]. Cutadapt tool [23] and Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME) version 1.8.0 [24] was used to generate operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using the open reference OTU picking strategy at a threshold of 97%, with U-CLUST against a Greengenes core set (gg_13_8) [25, 26]. The representative sequences were aligned against the Greengenes core set using PyNAST software [27]. The chimeric sequences were removed by ChimeraSlayer [28]. Taxonomy was assigned to each OTU using the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) classifier with a minimum confidence threshold of 80% [29]. The OTU table was further filtered to include OTUs present in at least three samples and randomly subsampled to contain 1498 reads per sample. After analysis of sequence data, genera that represented >1% of the total relative abundance in a NTC were identified as contaminants. Taxonomic families containing a contaminant were manually filtered out from the OTU table. A weighted UniFrac dissimilarity matrix was created in QIIME for the original and the filtered data. The UniFrac distances between samples were used to compare consecutively collected samples in bacteriologically stable quarters with randomly selected samples (i.e. samples taken from quarters with the same bacteriological finding by culture three or four days apart were compared to random values in the data set). This procedure was repeated both in the original and the filtered data set. In addition, the contamination identified herein were compared to the contamination identified by the “decontam” package in R [30].

Descriptive analysis on sequencing results and statistical analyses, multivariate analyses and contamination identification were performed using Microsoft Excel, PAST [31] and R [32] and statistical significance was set at the level P<0.05. The 16S rRNA gene sequences were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number PRJNA485047.

Results

Udder health and bacterial growth in milk

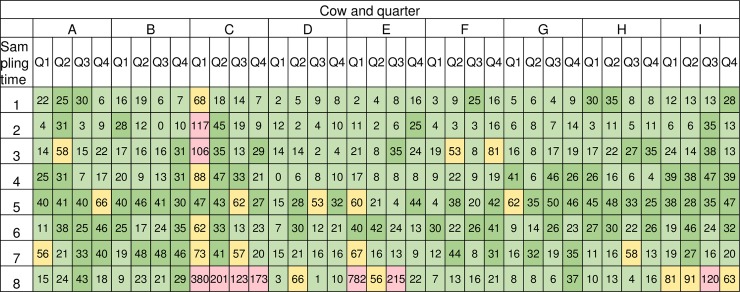

In this study the milk SCC of a majority of the quarters were stable and 96.9% (279/288) of the samples had a value below 100 000 cells/mL, averaging 17 195 cells/mL (Fig 1). The majority of the milk samples, 79.2% (228/288 samples), had no bacterial growth after 48 hours, 20 samples (6.9%) had sparse growth, 34 samples (11.8%) had moderate growth and six samples (2.1%) had abundant growth of bacteria after 48 hours (Table 1). Bacterial species identified by the Mastitis Laboratory at the National Veterinary Institute, Uppsala, Sweden were: Corynebacterium spp. (44 samples), mixed flora (15 samples) and Staphylococcus spp. (1 sample) (Table 1). Mixed flora was defined as growth of more than one phenotypically different CFU on the agar plate and were not further evaluated. Sixteen out of 36 quarters were bacteriological stable by culture throughout the study period, i.e. had the same bacterial species identified, or absence of bacteria, at all sampling points.

Fig 1. Milk somatic cell count (SCC) per cow, quarter and sampling time.

Milk SCC expressed as x 1000/mL, cow (A-I) and quarter (Q1-Q4) in columns and sampling time (1–8) in rows. Light green; 0–24, dark green; 25–50, yellow; 51–100, pink; >100 cells/mL.

Table 1. Bacterial growth in 10 μl of milk per cow, quarter and sampling time.

| Cow and quarter | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sampling time |

Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 |

| 1 | 0 | C2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | C1 | C2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | C1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | C1 | C2 | C1 | 0 | 0 | M2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | S1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | C1 | 0 | M1 | M1 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | C1 | 0 | C1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | C1 | C1 | C1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | M1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | C1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | C1 | M1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | C1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | C2 | C1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | M1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | C1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | M2 |

| 5 | C1 | C1 | 0 | C2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | C1 | C1 | C1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | C1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | C1 | C2 | C1 | C2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | C2 | C2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | C1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | C1 | C2 | C1 | M1 | 0 | M1 | C1 | C2 | C1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | M1 | M1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | C1 | C3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | C1 | C1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | M1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | M1 | 0 | M1 | 0 | C2 | 0 | 0 | C1 | 0 | 0 |

Cow (A-I) and quarter (Q1-Q4) in columns and sampling time (1–8) in rows. 0 indicates no growth, C = growth of Corynebacterium spp, M = growth of mixed bacterial flora, S = growth of Staphylococcus spp. Superscripts 1, 2, 3 indicate sparse (3–10 CFU), moderate (11–50 CFU) and abundant (>50 CFU) growth, respectively.

Microbiota in milk samples and negative controls

The 288 milk samples generated on average of 7 726 ±8355 quality controlled reads per sample (reads and DNA concentrations are provided in S1 Table). With the subsample threshold set to 1498 reads/sample, 278 milk samples were used for further analysis.

According to the sequencing results, four genera were present in more than 95% of all the milk samples; Methylobacterium, Achromobacter, Burkholderia and an unclassified genus in the family Oxalobacteriaceae. Together these genera represented 66% of the sequence data. Methylobacterium was the only genus present in all milk samples with average abundance of 57.9% (range 0.4–92.9%). Box plots for the ten most abundant genera are provided in S1 Fig.

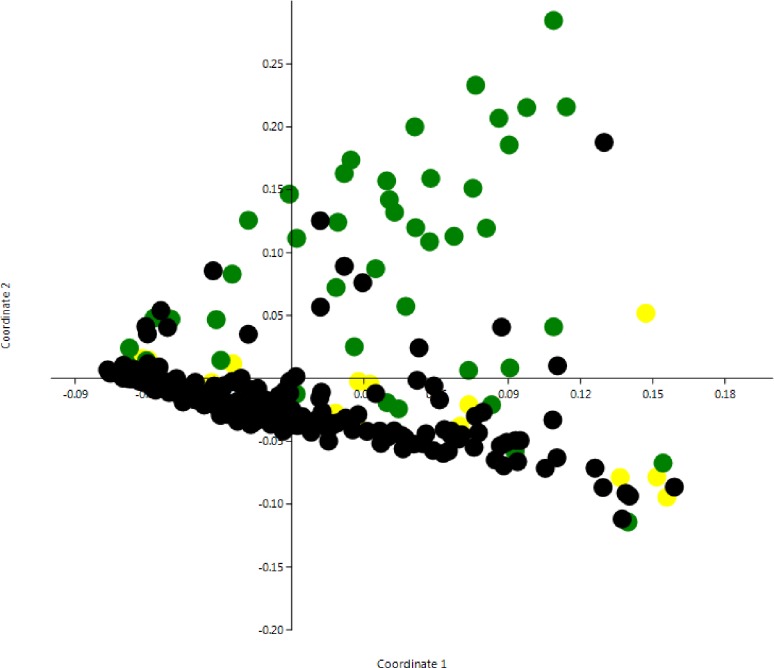

A principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Bray Curtis distances was applied on the sequence and culture dependent data to search for clustering patterns among the samples. The PCoA revealed that growth of Corynebacterium spp. was a major factor affecting dissimilarity in the milk samples (Fig 2). An analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) revealed that samples with bacterial growth (Corynebacterium or mixed flora) were significantly different from other samples (S3 Table).

Fig 2. Principal coordinates analysis with Bray-Curtis similarity index of milk samples in the study (n = 278).

Samples are color-coded based on bacterial growth; black = no growth, green = growth of Corynebacterium spp, yellow = growth of mixed bacterial flora.

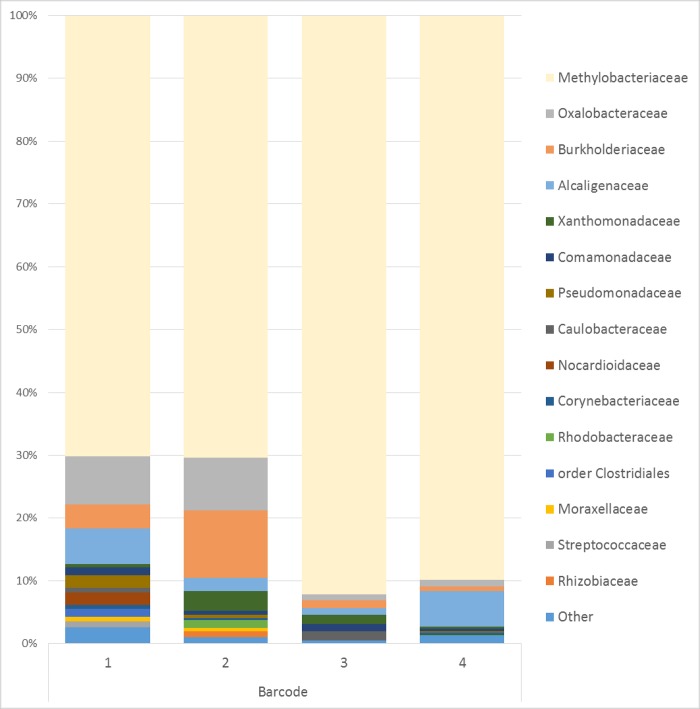

After DNA isolation and PCR amplification, seven out of 14 NTC had measurable amounts of DNA and were subsequently sequenced. Within the four barcodes used for the sequenced NTC, 47 different taxa were identified. The most predominant genus in the NTC’s, Methylobacterium, was present in all NTC’s and represented 70.0–92.2% of the data (Fig 3). In addition, Achromobacter, Burkholderia, Corynebacterium, Pseudomonas, Stenotrophomonas and unclassified genus in the family Oxalobacteraceae and Comamonadaceae were present in all sequenced NTC.

Fig 3. Relative abundance of the 15 most common families or order of bacteria found in NTC.

14 no-template DNA extraction controls (NTC’s) were individually processed and barcoded with a limited number of barcodes, 7 NTC’s marked with 4 different barcodes were included in sequencing.

Since Methylobacterium was detected in all milk samples and in all NTC’s we investigated if there were differences in (Methylobacterium) abundance, between DNA extraction batches with and without detectable amounts of DNA in the NTC. Regardless if the NTC for a specific DNA extraction batch contained or did not contain DNA, Methylobacterium was the most predominant genera in the associated milk samples. Moreover, there was no difference in relative abundance of Methylobacterium between milk samples prepared in DNA extraction batches with or without measurable amounts of DNA in NTC (p-value 0.75, t-test).

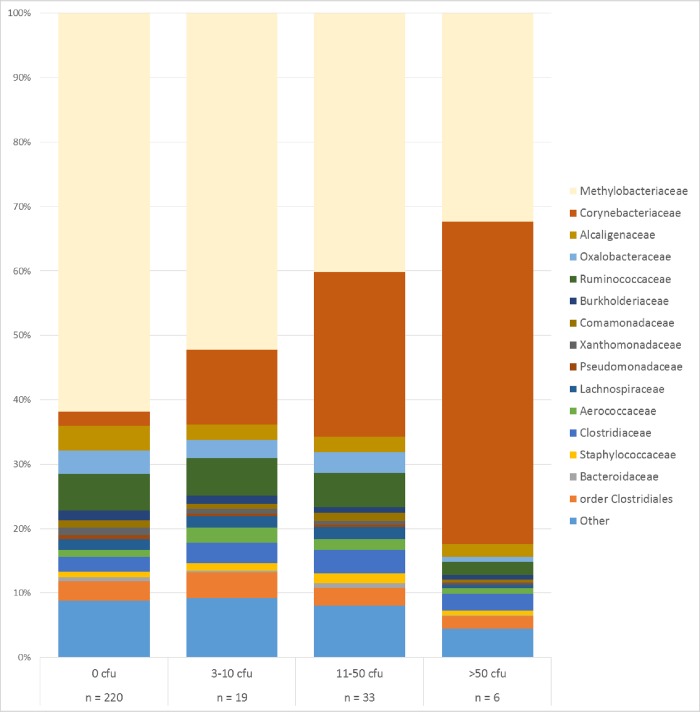

There was an association between the proportion of Methylobacterium and number of bacteria determined by culturing. In milk samples with no bacterial growth after 48 hours, Methylobacterium was the most predominant taxa with an average abundance of 61.8%. In samples with abundant growth (i.e. >50 CFU/10μl) Methylobacterium was present in significantly lower proportions (P<0.01, t-test) with an average abundance of 32.3% (Fig 4), these samples were instead dominated by Corynebacterium, which is in agreement with what was found on the agar plates. There was a decrease in number of identified taxa per milk sample with increased bacterial growth/biomass, a total of 460 different taxa were identified in milk samples with no bacterial growth while a total of 94 different taxa were identified in milk samples with abundant bacterial growth (>50 CFU/10μl milk).

Fig 4. Relative abundance of the 15 most common families or order of bacteria found in bovine milk samples.

Milk samples (n = 278) are grouped by number of colony forming units (CFU) in 10μl milk. Presence of Corynebacterium spp. was confirmed by culture and found in 44 milk samples.

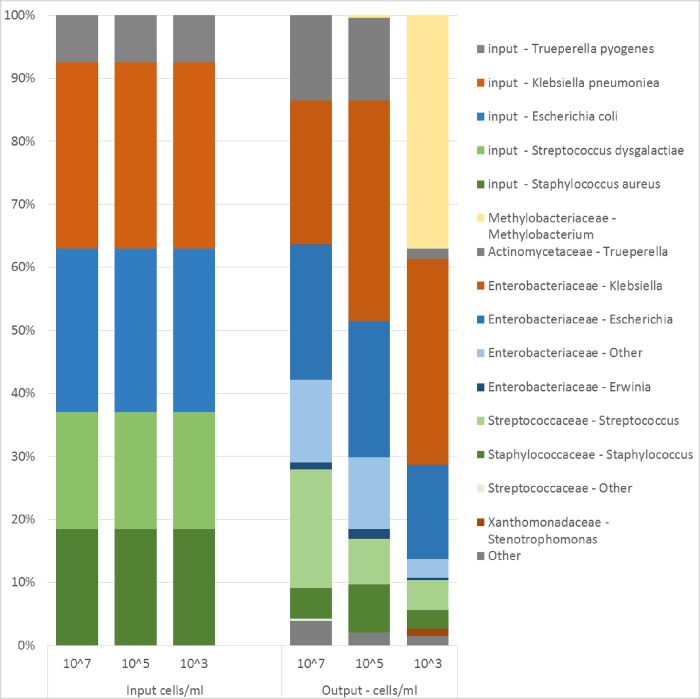

Mock community as positive control

The microbial analysis of the three mock community dilutions revealed the presence of a total of 21 different taxa. More than 96% of the sequence data in the two highest concentrations (5x107 and 5x105 cells/mL) were associated with the input bacteria whereas in the lowest concentration (5x103 cells/mL) only 60% of the sequence data originated from input bacteria. In the lowest concentration (5x103 cells/mL) Methylobacterium represented 37% of the total abundance (Fig 5), while this species accounted for less than 0.5% of the sequences when the bacterial concentration was higher than 105 cells/mL. There were also indications that sample processing (DNA extraction, PCR, choice of primer etc.) influenced the proportions of the taxa within the mock community. Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus dysgalactiae became less abundant in the sequence data compared to input, while Trueperella pyogenes became more abundant than expected. The Gram-negative Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae became more abundant in the sequence data than input and were correctly classified at the family level (Enterobacteriaceae). However at genus level Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae where classified as Klebsiella, Erwinia, Escherichia and “other”.

Fig 5. Relative abundance of input cells and the 10 most common genera found by sequencing in a mock community.

Input bacterial cells, corrected for number of 16S rRNA genes per species (left), and sequencing results (right) from a bacterial mock community at three different dilutions of a bacterial mix created from five commonly occurring udder pathogens.

Effect of data filtration and identified contaminants

An analysis of sequence data identified genera that represented >1% of the total relative abundance in a NTC as contaminants. Nine taxonomic families were found to contain at least one contaminant and were excluded from the data set. Consequently, the filtered data set did not contain any genera from the families; Alcaligenaceae, Burkholderiaceae, Caulobacteraceae, Methylobacteriaceae, Nocardioidaceae, Oxalobacteraceae, Pseudomonadaceae, Rhodobacteraceae or Xanthomonadaceae, a total of 39 genera in the data set belonged to these families. Contamination filtration led to a 72% reduction in available data from milk samples leaving 622 839 sequence reads for further analysis. The number of identified taxa decreased from 487 in the original data set to 438 in the filtered data set. After data filtration Corynebacterium and unclassified genus in the Ruminococcaceae and Clostridiaceae family were the most abundant genera, together they represented 33% of total abundance and were present in 94%, 96% and 72% of the milk samples respectively.

In order to study how the filtration method influenced the relation between samples, UniFrac distances between samples collected consecutively from the same cow and quarter were compared with UniFrac distances between randomly selected samples in the data set. Before filtration there was no difference in the UniFrac distance between consecutive and random comparisons (p-value 0.30, t-test). However in the filtered data set there was a significant difference between consecutive and random comparisons with larger UniFrac distances for random comparisons (p-value <0.01, t-test).

The recently published “decontam” R-package [30] was also used to identify contamination. The strict (0.5) threshold settings in the prevalence-based contaminant identification in the “decontam” R-package identified 32 contaminating taxa. Ten taxa were identified as contamination by both protocols, a list of identified contaminants is available in S2 Table, Corynebacterium was but Methylobacterium was not identified as a contaminant by the “decontam” R-package.

Discussion

The animal experiment for this study was designed to compare the milk microbiota within quarter over time, as well as between quarters and between animals over time. A large proportion of quarters had a similar bacteriological finding by culture throughout the study period indicating that bacteria findings by culture dependent methods were stable over time. Corynebacterium spp. was the most commonly isolated bacteria by culture and was repeatedly detected in milk from the same quarters adding further support that bacteriological response was stable over time. We aimed to study the composition and temporal stability of the milk microbiota using 16S amplicon sequencing. Despite a very careful treatment of the samples, with all DNA isolations carried out in a laminar air flow hood pretreated with UV light and cleaned with both 10% bleach and 70% ethanol, contamination from reagents and the laboratory environment had a pronounced effect on the results. Due to this contamination, characterization and assessment of temporal stability of the bovine milk microbiota via 16S rRNA sequencing proved difficult and is further discussed below.

When bacterial cell count determined by culture dependent analysis or manual counting was below 104 cells per mL, contaminating taxa became more dominant. This was observed both in sequence data generated from a created mock community as well as in milk samples where concentration of bacteria was determined by a culture-based approach. When the bacterial concentration in a created mock community corresponded to 5x103 cells/mL Methylobacterium, the major contaminant in this study, represented 37% of the sequences. Similar proportions of Methylobacterium was identified in milk samples when the bacterial concentration corresponded to 103−104 cells/mL. Noteworthy is an observed correlation between the relative abundance of Methylobacterium and abundance of bacterial growth in milk samples, where Methylobacterium became more abundant with fewer viable bacteria (Fig 4). These results are in line with previously published data from Salter et al. and Glassing et al. [6, 7] who reported thresholds of 103–104 bacterial cells/mL and 10 E. coli equivalent genomes per μl respectively. Thus, the evidence that low bacterial biomass 16S-based microbiota studies are prone to be contaminated is increasing.

Randomly occurring DNA contamination in a laboratory environment is challenging to overcome and milk samples can easily become contaminated either at sampling in the barn, or during laboratory sample processing. In this experiment precaution was taken to minimize and characterize contamination arriving from different steps but measurable amounts of DNA occurred in every other NTC from DNA extraction. Due to the small bacteriological biomass in the milk samples it was necessary to use many PCR-cycles. Using many PCR-cycles may enhance the impact of a contamination and introduce PCR-artefacts such as chimera sequences but was inevitable in this study. However, there was no statistical difference in relative abundance of Methylobacterium in milk samples prepared in batches where measurable amounts of DNA could be found in the NTC, compared with batches where no DNA could be found in the NTC. This led us to the conclusion that absence of visible bands or measurable amounts of DNA in NTC´s does not necessarily imply absence of contamination.

Methylobacterium is a genus consisting of 52 species of aerobic Gram-negative bacteria that are slow growing, commonly isolated from soil, leaf surface and fresh water and have capacity to form biofilms [33]. Methylobacterium has been reported to cause colonization and infection in immunocompromised humans [34] and has previously been reported as a contaminant in microbiome studies [6, 35]; to our knowledge Methylobacterium has never been isolated from milk of dairy cows.

Different DNA extraction methods can affect and skew the relative abundance of bacteria present in a mock community and some DNA extraction methods are more prone to introduce contamination [18, 36]. Further, in each step to prepare samples for sequencing there is a risk that biases are introduced (thoroughly discussed by Pollock et al. [17]). We used the Power food DNA extraction kit from MO BIO since this according to the literature [37] and personal experience yielded most DNA from the milk samples. From the sequenced mock community we noticed that the method introduced some biases in the distribution of taxa. Sequencing of the mock community led to an overestimation of Gram-negative bacteria and an underestimation of two out of three Gram-positive bacteria (Fig 5) an effect that might be related to the DNA extraction method used. We also noticed that partial sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene might not be sufficient for correct annotation of all present bacteria since E. coli and K. pneumoniae were annotated into four different genera, although, all within the Enterobacteriaceae family.

Identification of contaminants in this study was based on presence of a taxa in NTC and a threshold of >1% relative abundance. Davis et al. [30] reason in a similar manner for the prevalence-based contaminant identification in the R-package “decontam”. Accordingly; prevalence of contaminants will be higher in negative controls than in true samples due to the absence of competing DNA in the sequencing process. The prevalence-based contaminant identification in the “decontam” R-package also include a stricter threshold option that will identify all sequences that are more prevalent in negative controls than in positive samples as contaminants. Here, Methylobacterium was not identified as a contaminant by the “decontam” R-package, likely due to the presence of Methylobacterium in all samples and high prevalence in the milk samples. In conclusion, the “decontam” R-package is a highly useful tool and complement for identification of contaminating taxa.

Evaluation of the data filtering of contaminants in this data set was made under the assumption that a milk microbiota stable over a short time period exists, in the absence of disease and major environmental changes. This assumption was based on the fact that in the bovine udder each quarter (mammary gland) functions as a separate unit. Intra-mammary infection often occurs in a quarter with no immunological or bacterial response in neighboring quarters. Studies of the bovine milk microbiota have confirmed that the microbiota in two quarters within the same cow can be substantially different [2, 11] and also that the microbiota profile of quarters within the same cow are more similar to each other than quarters of other cows [38]. It has also been shown that the human milk microbiota often, yet not always, is stable over time [39]. Thus, we expected the difference in microbiota between two samples to be smallest if they were taken from the same quarter from two consecutive sampling points that had the same bacteriological response by culture. With the weighted UniFrac dissimilarity matrix created in QIIME for the original and the filtered data, distances for consecutive samplings in bacteriologically stable quarters were compared to distances for randomly selected comparisons in the data set. In the original data set there was no difference between consecutive and random comparisons, while in the filtered data set there was a significant difference between consecutive and random comparisons, with larger similarity between consecutive comparisons. This demonstrates that even if the data filtration contribute to a substantial reduction in sequence data it can improve the possibility to find biologically relevant associations in milk microbiota data.

In this study Corynebacterium was the most commonly isolated bacteria in milk samples by culture but Corynebacterium DNA was also present in all NTC. With the threshold set to >1% abundance in a NTC for a genera to be categorized as a contaminant, Corynebacterium did not meet the requirements and was subsequently not filtered from the data set, consequently Corynebacterium became the most abundant genus in the data after filtration. Interestingly Corynebacterium isolated by culture was a major factor affecting dissimilarity before filtration even though it was not very abundant (S3 Table). Of the nine taxonomic families that were filtered from the data set, none is known to contain major mastitis causing pathogens. In the family Pseudomonadaceae, one genus (Pseudomonas aeruginosa) is known to cause mastitis in dairy cows but is considered a rare udder pathogen in Sweden [40]. A similar strategy to exclude contaminating taxa used here was discussed by Glassing et al. [7] but rejected due to too large data loss and loss of known endogenous taxa. The method for filtration used herein did indeed lead to a great reduction in available data but had a small effect on the number of identified taxa and only had a minor impact on known endogenous taxa in the bovine milk microbiota.

In this study we have shown that the impact of contamination in samples with a low biomass can conceal biologically relevant associations. Further we conclude that proper identification of the contaminants is necessary in order to evaluate the overall impact of the contamination, and that absence of measurable amounts of DNA in negative controls does not imply absence of contamination.

Supporting information

Relative abundance of the ten most abundant genera before data filtration separated by bacterial growth in 10 μl of milk. The 25–75 percent quartiles and median value are shown within the box, whiskers represent value less than 1.5 times box height, values 1.5–3 times box height are shown as circles and values >3 times box height are shown as stars.

(PNG)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

One-way ANOSIM with Bonferroni corrected p-values based on BrayCurtis similarity index, samples are classified based on the type of bacterial growth identified by culture. One sample with growth of Staphylococcus omitted.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The Swedish Research Council Formas is gratefully acknowledged for financial support (2012-1365-22729-42).

Sequencing was performed by the SNP&SEQ Technology Platform in Uppsala. The facility is part of the National Genomics Infrastructure (NGI) Sweden and Science for Life Laboratory. The SNP&SEQ Platform is also supported by the Swedish Research Council and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

This work was supported by the SLU Bioinformatics Infrastructure (SLUBI), Uppsala, Sweden and the National Bioinformatics Infrastructure in Sweden (NBIS) supported by the Swedish Research Council.

Data Availability

The 16S rRNA gene sequences are deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number PRJNA485047. The project will be released on 9/7/2019. However, data is available through the following link: https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA485047?reviewer=vqfummt0kvlb0tak59n0404r1k.

Funding Statement

The Swedish Research Council Formas (http://www.formas.se/en/) financially supported this study by a grant (2012-1365-22729-42) rewarded to SA, JD, MM, KPW, Kö. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Oikonomou G, Machado VS, Santisteban C, Schukken YH, Bicalho RC. Microbial diversity of bovine mastitic milk as described by pyrosequencing of metagenomic 16s rDNA. PloS one. 2012;7(10):e47671 10.1371/journal.pone.0047671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuehn JS, Gorden PJ, Munro D, Rong R, Dong Q, Plummer PJ, et al. Bacterial community profiling of milk samples as a means to understand culture-negative bovine clinical mastitis. PloS one. 2013;8(4):e61959 10.1371/journal.pone.0061959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickson RP, Huffnagle GB. The Lung Microbiome: New Principles for Respiratory Bacteriology in Health and Disease. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(7):e1004923 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aagaard K, Ma J, Antony KM, Ganu R, Petrosino J, Versalovic J. The placenta harbors a unique microbiome. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(237):237ra65 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng J, Xiao X, Zhang Q, Mao L, Yu M, Xu J. The Placental Microbiome Varies in Association with Low Birth Weight in Full-Term Neonates. Nutrients. 2015;7(8):6924–37. 10.3390/nu7085315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salter SJ, Cox MJ, Turek EM, Calus ST, Cookson WO, Moffatt MF, et al. Reagent and laboratory contamination can critically impact sequence-based microbiome analyses. BMC Biol. 2014;12:87 10.1186/s12915-014-0087-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glassing A, Dowd SE, Galandiuk S, Davis B, Chiodini RJ. Inherent bacterial DNA contamination of extraction and sequencing reagents may affect interpretation of microbiota in low bacterial biomass samples. Gut Pathog. 2016;8:24 10.1186/s13099-016-0103-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lauder AP, Roche AM, Sherrill-Mix S, Bailey A, Laughlin AL, Bittinger K, et al. Comparison of placenta samples with contamination controls does not provide evidence for a distinct placenta microbiota. Microbiome. 2016;4(1):29 10.1186/s40168-016-0172-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeurink PV, van Bergenhenegouwen J, Jimenez E, Knippels LM, Fernandez L, Garssen J, et al. Human milk: a source of more life than we imagine. Benef Microbes. 2013;4(1):17–30. 10.3920/BM2012.0040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oikonomou G, Bicalho ML, Meira E, Rossi RE, Foditsch C, Machado VS, et al. Microbiota of cow's milk; distinguishing healthy, sub-clinically and clinically diseased quarters. PloS one. 2014;9(1):e85904 10.1371/journal.pone.0085904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganda EK, Bisinotto RS, Lima SF, Kronauer K, Decter DH, Oikonomou G, et al. Longitudinal metagenomic profiling of bovine milk to assess the impact of intramammary treatment using a third-generation cephalosporin. Sci Rep. 2016;6:37565 10.1038/srep37565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganda EK, Gaeta N, Sipka A, Pomeroy B, Oikonomou G, Schukken YH, et al. Normal milk microbiome is reestablished following experimental infection with Escherichia coli independent of intramammary antibiotic treatment with a third-generation cephalosporin in bovines. Microbiome. 2017;5(1):74 10.1186/s40168-017-0291-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falentin H, Rault L, Nicolas A, Bouchard DS, Lassalas J, Lamberton P, et al. Bovine Teat Microbiome Analysis Revealed Reduced Alpha Diversity and Significant Changes in Taxonomic Profiles in Quarters with a History of Mastitis. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:480 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doyle CJ, Gleeson D, O'Toole PW, Cotter PD. Impacts of Seasonal Housing and Teat Preparation on Raw Milk Microbiota: a High-Throughput Sequencing Study. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2017;83(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Derakhshani H, Plaizier JC, De Buck J, Barkema HW, Khafipour E. Association of bovine major histocompatibility complex (BoLA) gene polymorphism with colostrum and milk microbiota of dairy cows during the first week of lactation. Microbiome. 2018;6(1):203 10.1186/s40168-018-0586-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rainard P. Mammary microbiota of dairy ruminants: fact or fiction? Vet Res. 2017;48(1):25 10.1186/s13567-017-0429-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollock J, Glendinning L, Wisedchanwet T, Watson M. The Madness of Microbiome: Attempting To Find Consensus "Best Practice" for 16S Microbiome Studies. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2018;84(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abusleme L, Hong BY, Dupuy AK, Strausbaugh LD, Diaz PI. Influence of DNA extraction on oral microbial profiles obtained via 16S rRNA gene sequencing. J Oral Microbiol. 2014;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Segal LN, Alekseyenko AV, Clemente JC, Kulkarni R, Wu B, Gao Z, et al. Enrichment of lung microbiome with supraglottic taxa is associated with increased pulmonary inflammation. Microbiome. 2013;1(1):19 10.1186/2049-2618-1-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oliver SP, Gonzalez RN, Hogan JS, Jayarao BM, Owens WE. Microbiological Procedures for the Diagnosis of Bovine Udder Infection and Determination of Milk Quality. 4 ed. NMC Inc, Verona, WI, USA: The National Mastitis Council; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hugerth LW, Wefer HA, Lundin S, Jakobsson HE, Lindberg M, Rodin S, et al. DegePrime, a program for degenerate primer design for broad-taxonomic-range PCR in microbial ecology studies. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2014;80(16):5116–23. 10.1128/AEM.01403-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muller B, Sun L, Westerholm M, Schnurer A. Bacterial community composition and fhs profiles of low- and high-ammonia biogas digesters reveal novel syntrophic acetate-oxidising bacteria. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2016;9:48 10.1186/s13068-016-0454-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnetjournal. 2011;17(1). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7(5):335–6. 10.1038/nmeth.f.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(19):2460–1. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rideout JR, He Y, Navas-Molina JA, Walters WA, Ursell LK, Gibbons SM, et al. Subsampled open-reference clustering creates consistent, comprehensive OTU definitions and scales to billions of sequences. PeerJ. 2014;2:e545 10.7717/peerj.545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caporaso JG, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, DeSantis TZ, Andersen GL, Knight R. PyNAST: a flexible tool for aligning sequences to a template alignment. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(2):266–7. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haas BJ, Gevers D, Earl AM, Feldgarden M, Ward DV, Giannoukos G, et al. Chimeric 16S rRNA sequence formation and detection in Sanger and 454-pyrosequenced PCR amplicons. Genome Res. 2011;21(3):494–504. 10.1101/gr.112730.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2007;73(16):5261–7. 10.1128/AEM.00062-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis NM, Proctor DM, Holmes SP, Relman DA, Callahan BJ. Simple statistical identification and removal of contaminant sequences in marker-gene and metagenomics data. Microbiome. 2018;6(1):226 10.1186/s40168-018-0605-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hammer O, Harper D, Ryan P. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica. 2001;4(1). [Google Scholar]

- 32.R Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kovaleva J, Degener JE, van der Mei HC. Methylobacterium and Its Role in Health Care-Associated Infection. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2014;52(5):1317–21. 10.1128/JCM.03561-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanders JW, Martin JW, Hooke M, Hooke J. Methylobacterium mesophilicum infection: case report and literature review of an unusual opportunistic pathogen. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2000;30(6):936–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barton HA, Taylor NM, Lubbers BR, Pemberton AC. DNA extraction from low-biomass carbonate rock: an improved method with reduced contamination and the low-biomass contaminant database. J Microbiol Methods. 2006;66(1):21–31. 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brooks JP, Edwards DJ, Harwich MD Jr., Rivera MC, Fettweis JM, Serrano MG, et al. The truth about metagenomics: quantifying and counteracting bias in 16S rRNA studies. BMC Microbiol. 2015;15:66 10.1186/s12866-015-0351-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quigley L, O'Sullivan O, Beresford TP, Paul Ross R, Fitzgerald GF, Cotter PD. A comparison of methods used to extract bacterial DNA from raw milk and raw milk cheese. J Appl Microbiol. 2012;113(1):96–105. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05294.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Derakhshani H, Plaizier JC, De Buck J, Barkema HW, Khafipour E. Composition of the teat canal and intramammary microbiota of dairy cows subjected to antimicrobial dry cow therapy and internal teat sealant. Journal of dairy science. 2018;101(11):10191–205. 10.3168/jds.2018-14858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hunt KM, Foster JA, Forney LJ, Schutte UM, Beck DL, Abdo Z, et al. Characterization of the diversity and temporal stability of bacterial communities in human milk. PloS one. 2011;6(6):e21313 10.1371/journal.pone.0021313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ericsson Unnerstad H, Lindberg A, Persson Waller K, Ekman T, Artursson K, Nilsson-Ost M, et al. Microbial aetiology of acute clinical mastitis and agent-specific risk factors. Vet Microbiol. 2009;137(1–2):90–7. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Relative abundance of the ten most abundant genera before data filtration separated by bacterial growth in 10 μl of milk. The 25–75 percent quartiles and median value are shown within the box, whiskers represent value less than 1.5 times box height, values 1.5–3 times box height are shown as circles and values >3 times box height are shown as stars.

(PNG)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

One-way ANOSIM with Bonferroni corrected p-values based on BrayCurtis similarity index, samples are classified based on the type of bacterial growth identified by culture. One sample with growth of Staphylococcus omitted.

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

The 16S rRNA gene sequences are deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number PRJNA485047. The project will be released on 9/7/2019. However, data is available through the following link: https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA485047?reviewer=vqfummt0kvlb0tak59n0404r1k.