Abstract

Bullying is an adverse childhood experience that is more common among youth with special needs and is associated with increased psychopathology throughout the lifespan. Individuals with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q) represent one group of special needs youth who are at increased risk for bullying due to co-occurring genetically-mediated developmental, physical, and learning difficulties. Furthermore, individuals with 22q are at increased risk for developing psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia. However, there is a paucity of research exploring the impact of bullying on individuals with 22q and the possible impact this has on risk for psychosis in this population. To explore this relationship using existing research the goals of the review are: (i) to explore the nature of bullying among youth with special needs, and (ii) to discuss its potential role as a specific risk factor in the development of adverse outcomes, including psychosis symptoms. We reviewed the relationship between bullying and its short and long-term effects on the cognitive, social, and developmental functioning of typically developing individuals and those with special needs. We propose an interactive relationship between trauma, stress, and increased psychosis risk among youth with 22q with a history of bullying. The early childhood experience of trauma in the form of bullying promotes an altered developmental trajectory that may elevate the risk for maladaptive functioning and subsequent psychotic disorders, particularly in youth with genetic vulnerabilities. Therefore, we conclude the experience of bullying among individuals with 22q should be more closely examined.

Keywords: 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, DiGeorge syndrome, Bullying, Psychosis, Trauma, Chronic stress, Victimization

1. Introduction

The vulnerability-stress model for psychosis risk posits that interactions between endogenous and exogenous factors contribute to the development of psychosis spectrum disorders. This model hypothesizes that certain biological vulnerabilities (e.g., genetic predisposition, neurophysiological dysregulation, etc.) interact with environmental stressors (e.g., perinatal issues, adverse experiences, substance misuse, etc.) and lead to the emergence of psychosis symptoms (Nuechterlein and Dawson, 1984). When individuals possess a genetic or biological vulnerability to psychosis, they can only withstand a certain amount of environmental stressors; once this threshold of stress is surpassed, there is higher risk for the development of psychosis (Zubin and Spring 1977). From this perspective, the experience of trauma increases one’s subjective stress and, therefore, leaves an individual with greater susceptibility to developing psychopathology.

One population has demonstrated unique genetic vulnerability to the development of psychosis: individuals with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q; Stoddard et al., 2010). Chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q) results from the most common de novo microdeletion and occurs in approximately 1 in 2000–4000 live births (Botto et al., 2003; Grati et al., 2015; Shprintzen, 2008). The chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome is typically associated with a variety of complex medical (e.g., cleft palate, congenital heart defects, facial anomalies, immune function, velopharyngeal dysfunction), developmental (e.g., speech difficulties, learning/developmental disorders, poor motor/balance and coordination, social deficits), and psychiatric issues (e.g., psychosis, anxiety, ASD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; Goldenberg et al., 2012; Gothelf, 2014; Stoddard et al., 2010; Tang et al., 2014). Individuals with 22q not only demonstrate a genetic vulnerability for psychiatric disorders, but are also more likely to endorse the presence of a variety of stressors. Additionally, these individuals are more likely to experience repeated or chronic stress than their typically developing counterparts. One such form of chronic stress is bullying. Although currently limited, emerging research on bullying among youth with disabilities report that they are 1.5 times more likely to be victimized (Blake et al., 2012) and become involved in bullying through various roles (McLaughlin et al., 2010; Rose et al., 2015; Rose et al., 2011).

Exposure to chronic stress, like bullying, in conjunction with increased genetic risk may have a significant impact on the development of psychosis in this population. To date, there has not been an in-depth investigation into the effect of bullying in individuals with 22q in general, let alone the possible relationship this form of chronic stress has on risk for psychosis specifically. We propose that bullying may have an even greater impact on individuals with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome due to the increased risk associated with multiple physical, developmental, intellectual, and psychiatric vulnerabilities. In this review, we first present 1) an overview of the impact of stress on psychological and functional outcomes in 22q, 2) the impact of bullying for individuals with and without special needs, and 3) the potential role of bullying as a chronic stressor leading to expression of psychosis risk in 22q.

2. 22Q11.2 Deletion syndrome

As previously stated, individuals with 22q show higher rates of psychiatric comorbidities particularly for anxiety disorders (36%), ADHD (37%) and psychosis spectrum disorders (10% in adolescents, 41% in adults) according to a recent study conducted by Schneider et al. (2014). Additionally, a study by Yi et al. (2014) illustrated that those with 22q and congenital heart disease (CHD) had greater risk for developing psychosis spectrum disorders with 71% of the sample meeting criteria. Most individuals with 22q have borderline to low average IQ scores, and they typically perform better in verbal than non-verbal tasks (De Smedt et al., 2007; Woodin et al., 2001). Individuals with 22q have significant global and domain specific cognitive impairments which have been shown to correlate with not only role but social functioning (Campbell et al., 2015).

Despite the increased risk factors for bullying in this population, there are currently no known studies that have specifically examined bullying perpetration or victimization among individuals with 22q. As a relevant comparison, children with chronic illness, complex medical conditions (e.g., asthma, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes), and motor skills/coordination difficulties all have been noted to be at increased risk for bullying victimization (Bejerot et al., 2013; Faith et al., 2015; Pittet et al., 2010). Given the host of medical, physical, and neurodevelopmental challenges that typically present in individuals with 22q, there is a real concern about their increased risk factors for bullying victimization.

3. Impact of stress on individuals with 22Q

3.1. Prevalence of anxiety disorders

Research on individuals with 22q suggests that stress and anxiety levels are important considerations in the development of psychosis. In general, early Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) increase the risk of developing later anxiety disorders and are associated with atypical development of physiological stress responses (Elzinga et al., 2008). Youth with 22q commonly experience anxiety disorders such as specific phobia, separation anxiety, and generalized anxiety disorder ranging from 32% to 61% (Dekker and Koot, 2003; Gothelf et al., 2007). Additionally, due to the medical comorbidities of the deletion (e.g. cleft palate, heart abnormalities), youth with 22q also experience a number of medical procedures and surgeries early in their life, which can increase the risk of anxiety disorders due to the stress of medical trauma experienced (Beaton and Simon, 2010). Higher anxiety scores among youth with 22q have also been associated with lower adaptive functioning (Angkustsiri et al., 2012). A significant negative correlation is noted among youth with 22q who endorse symptoms associated with fear of parental separation and fear of physical injury with their adaptive functioning (Angkustsiri et al., 2012). Individuals with 22q who go on to develop schizophrenia were more likely to have accompanying symptoms of anxiety and lower verbal IQ scores over time (Goldenberg et al., 2012). Given the complex nature of the role that stress and anxiety plays on the psychopathology of youth with 22q, additional research is warranted to determine how elevated levels of stress and comorbid anxiety disorders contribute to the emergence of psychosis symptoms in this population.

3.2. Social cognition and functioning

Furthermore, social cognition deficits have been identified in the development of psychosis in 22q. Specifically, in youth with 22q, theory of mind is a significant predictor in the development of positive symptoms, while processing speed is a significant predictor of negative symptoms (Jalbrzikowski et al., 2012). Similar to individuals with schizophrenia without 22q, social cognition impairments (e.g., emotional processing, theory of mind) have also been reported, along with some difficulty among their first-degree relatives (Jalbrzikowski et al., 2012).

Social relationships have been suggested as an important buffer against traumatic experiences (Yang and McLoyd, 2015). Beaton and Simon (2010) highlighted that the role of parents’ coping ability and level of socio-emotional support may contribute as a risk or protective factor psychosis risk for youth with 22q. Due to their early medical, developmental, and learning difficulties, youth with 22q come to rely on their parents for most of their daily needs and may continue to do so for a longer duration of time compared to their same-aged peers, depending on their adaptive functioning abilities and independent living skills. Thus, it would make sense that when bullying is an issue for youth with 22q, their parents’ coping abilities, modelled ways of dealing with everyday stressors associated with interpersonal conflicts, and level of social support would contribute to some extent in youth’s level of chronic stress, thereby impacting their risk or protection from developing psychosis (Beaton and Simon, 2010).

4. Bullying involvement and related outcomes

Bullying is an act of repeated aggression or intimidation towards another where an imbalance in power exists between individuals (Arseneault et al., 2010; Olweus, 1993; Vaillancourt et al., 2009). It is also a form of adverse childhood experience (ACE (Radford et al., 2013); which usually involves some form of physical violence, intimidation, ridicule, name-calling, social exclusion, and/or extortion. Early research on the nature of bullying considered it a common psychosocial problem during school age years, and the general public viewed bullying as a typical childhood experience that is typically resolved (Arseneault et al., 2010).

Early adolescence (ages 12–14) marks the highest prevalence rates of bullying victimization at 25–27% (Lessne and Yanez, 2016; Whitney et al., 1992). Recent national data suggests that 20% of school aged youth are the victims of bullying during an academic year (Lessne and Yanez, 2016). Researchers have identified groups that are specifically vulnerable to bullying, such as lesbian, gay and other sexual minority individuals, youth with weight problems, and those with learning/developmental disabilities.

As previously stated, bullying is a form of adverse childhood experience (ACE), and the number and chronic nature of ACES experienced by an individual is associated with health outcomes. There are three roles involved in a given bullying situation: 1) the pure “bully” (i.e., perpetrates, but no victimization); 2) the “bully/victim” (i.e., has been a bully and a victim); and 3) the pure “victim” (i.e., has never been a bully; Berger, 2007; Wolke et al., 2014). Olweus (2001) introduced a more nuanced definition of the various roles involved in a bullying situation (e.g., students who bully, followers, passive bullies); we refer readers to this work for additional information.

Bullying victimization occurs in 1 out of 5 school-aged youth (Lessne and Yanez, 2016). Prevalence of bullying victimization is comparable across the biological sexes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014; Finkelhor et al., 2015). In contrast, males are more likely to be bullying perpetrators and bully/victims than females (Cook et al., 2009). Due to the overt nature of physical bullying, adults (i.e., school staff, parents) tend to be more aware of its occurrence when it involves males than females (Undheim and Sund, 2010). Somewhat higher rates of victimization occur among Caucasians (21.6%) and African-Americans (24.7) (Lessne and Yanez, 2016).

Victimization is more common for youth with low self-esteem and who are socially isolated, have poor interpersonal skills, and those who are perceived as “different” or “easy targets” (Arseneault et al., 2010; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). Risk factors for bullying victimization are based on both environmental factors (e.g., low socioeconomic status, school overcrowding, and child maltreatment in the home) (Arseneault et al., 2010; Barnes et al., 2006; Shields and Cicchetti, 2001; Wolke et al., 2014) and genetic factors (e.g., temperament, aggression, internalizing problems, externalizing problems, existing medical/neurodevelopmental vulnerabilities) (Arseneault et al., 2010; Schreier et al., 2009; Shakoor et al., 2015). Several studies indicated that heritable traits accounted for approximately 35% of the increased propensity for bullying victimization (Arseneault et al., 2010; Schreier et al., 2009; Shakoor et al., 2015). This presumes that there is no single cause for bullying, and that various individual, familial, and environmental factors are at play (Olweus et al., 1999).

Studies show that any involvement in bullying (i.e., as a pure bully, bully/victim, or pure victim) is associated with poorer psychological functioning (Kelleher et al., 2008; Wolke et al., 2014) in both childhood and adulthood. In childhood, bullying perpetration is linked to higher rates of maladjustment, substance use, truancy, vandalism, aggressive behaviors (e.g., carrying weapons), school dropout, psychosomatic problems, and increased risk for psychosis at age 18 (Gini, 2008; Nansel et al., 2001; Olweus, 1993; Solberg and Olweus, 2003; Wolke et al., 2014). Victims of bullying are more likely to develop depressive and anxiety symptoms, sleep problems, and experience poor academic functioning (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). Additionally, the experience of being a bully/victim results in an even greater risk of developing externalizing symptoms (aggression, conduct problems), internalizing symptoms (depression, suicidality), negative sense of self and others, poor social skills, peer rejection, severe psychopathology, physical health concerns, and higher adjustment problems than pure victims (Arseneault et al., 2010; Arseneault et al., 2006; Holt et al., 2015; Hunter et al., 2014; National Academies of Sciences, 2016). In adulthood, bullying history has been associated with a variety of poor long-term outcomes, with serious mental illness and psychosis being the most significant (Ashford et al., 2012; Bentall et al., 2012; M. L. Campbell and Morrison, 2007; De Loore et al., 2007; Kelleher et al., 2008; Kelleher et al., 2013; Lataster et al., 2006; Tunnard et al., 2014).

4.1. Bullying risks and outcomes related to youth with special needs

ACEs pose added negative implications to the general course of childhood development, and it may be more detrimental to youth with concurrent disability status, medical issues, and/or neurodevelopmental disorders. A substantial number of studies have confirmed that the rate of bullying victimization is higher among youth with special needs (60%) in comparison to typically developing (TD) children (10–27%; (Estell et al., 2009; Nansel et al., 2004; Thompson et al., 1994; Whitney et al., 1992). Individuals with disabilities are twice as likely to be involved in bullying victimization (Rose and Monda-Amaya, 2011; Whitney et al., 1992) in comparison to TD youth (Whitney et al., 1992).

Despite their disability status, studies indicate that youth with special needs also participate as bully/victims and bullying perpetrators (Maïano et al., 2016; Rose et al., 2015; Rose and Monda-Amaya, 2011). A study by Maïano et al. (2016) showed that bullying experiences in youth with special needs includes participation as victims (36.3%), bully/victims (25.2%), and bullies (15.1%). Interestingly, the prevalence rates obtained for bullying perpetration among youth with intellectual disabilities (ID) were similar to those from studies on TD youth (Due and Holstein, 2008; Nansel et al., 2004). A study by Schrooten et al. (2016) showed that adolescents with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) endorsed higher bullying perpetration towards others(6.2%) than TD (3.9%) despite having greater social impairment. Bullying perpetration by youth with special needs may be due to previously learned behaviours from school-aged peers, or as a way to address past victimization (Schrooten et al., 2016; Whitney et al., 1992).

Further variability in the bullying and victimization prevalence rates among different subgroups of youth with special needs have been indicated (Rose and Monda-Amaya, 2011; Van Roekel, Scholte and Didden, 2010). For youth with moderate to mild intellectual disability (ID), the risk for bullying victimization is higher compared to children in mainstream classrooms (Thompson et al., 1994). In general, low social support (i.e., few peer friendships) was identified as a risk factor for bullying among youth with special needs (Thompson et al., 1994). As such, there is an evident need to protect the vulnerable youth with special needs from avoidable harm.

5. The interplay of bullying and vulnerability in psychosis symptom development for 22Q

Genetic risk for the development of psychosis has been well documented in individuals with 22q. Studies have shown similar genetic and enzymatic disruptions in individuals with 22q and those with schizophrenia. Specifically, studies have shown disruption in Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) which is a gene that encodes a key dopa-mine catabolic enzyme. This gene has been implicated in genetic models of schizophrenia and is notably located in the area of deletion associated with 22q11 deletion syndrome. Similarly, proline dehydrogenase (PRODH) is gene that is involved in glutamate production and has been shown to be both affected by the microdeletions associated with 22q and correlated with development of juvenile onset schizophrenia. A comprehensive review of the genetic risk and vulnerability for the development of psychosis in individuals with 22q can be found here (Williams and Owen, 2004).

Individuals with 22q are uniquely vulnerable to experience both bullying and the development of psychosis spectrum disorders. Several studies on youth with 22q have attributed it to the compounding effects of chronic stress, anxiety, and trauma on poor adaptive functioning and increased risk for psychopathology (Angkustsiri et al., 2012; Beaton and Simon, 2010; Gothelf et al., 2007; Schneider et al., 2014). Beaton and Simon (2010) proposed that a cascade of chronic elevated stress, negative life events, and poor coping skills among youth with 22q place them at elevated risk for psychosis.

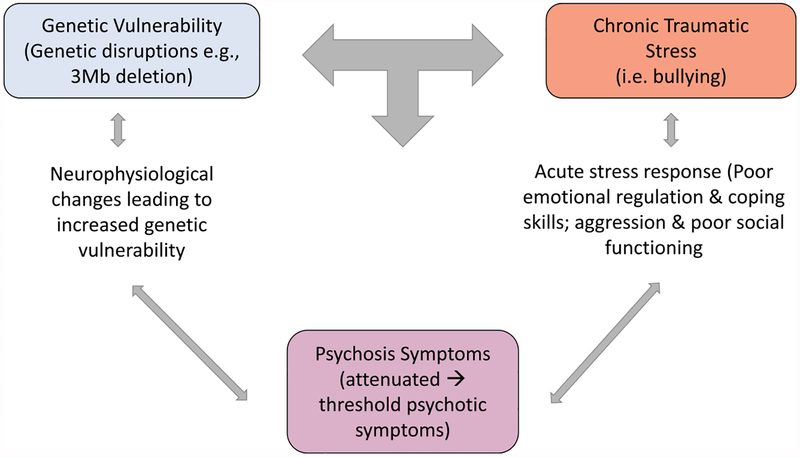

A recent review on the relationship between trauma and psychosis risk among CHR individuals suggests an initial genetic vulnerability that interacts with traumatic experiences (Mayo et al., 2017). The interplay between genetics and early traumatic events places individuals at an altered developmental trajectory and at greater risk for psychotic-like experiences. With the emergence of subthreshold symptoms of psychosis, one is exposed to increased risk for future instances of trauma. This proposed trauma-psychosis relationship offers a promising way of further understanding the relationship between bullying and psychosis risk among individuals with 22q. Additional research is needed to investigate the interaction between the 22q population’s traumatic experiences (specifically bullying) and elevated psychosis risk (see Fig. 1). As can be seen in Fig. 1 the interplay between stress and genetic vulnerability is cyclical. An initial stress-related insult on genetically vulnerable individuals can lead to attenuated psychosis symptoms. Continued stress then exacerbates existing symptoms, possibly contributing to threshold psychotic experiences. We will discuss these dynamic interactions below.

Fig. 1.

Interaction between genetic risk, chronic stress, and psychosis.

5.1. Early and chronic stress

In infancy and toddlerhood, many children with 22q are affected by multiple medical and immune system complications, which often lead to early invasive, complex surgeries, and possibly repeated medical interventions. Individuals with 22q become increasingly aware of their individual differences in academics and social abilities from TD peers in the school setting. Social adjustment to their same-aged classmates may be more challenging and associated with increased shyness, withdrawal from others, and poorer self-image or self-esteem due to difficulties in speech and differences in physical appearance or abilities. In addition, youth with 22q who have ID and poorer adaptive functioning abilities may be prone to increased risk for bullying and victimization. As explained by Angkustsiri et al. (2014), it may be expected that, with continued exposure to negative social interactions, youth with 22q would experience increased anxiety in emotional difficulties due to poor social competence. Consequently, such repeated and chronic stressors during critical developmental periods can lead to the dysregulation of their hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Lupien et al., 2005; McEwen, 2014). The early negative experience of bullying victimization may promote HPA axis dysregulation and possible exhaustion of coping resources. Indeed, a dose-response relationship has been indicated regarding the number of victimization events in early childhood and the increased risk for psychosis symptoms in early adolescence (Arseneault et al., 2010; Bentall et al., 2012; Kelleher et al., 2013; Schreier et al., 2009). Over time, it is possible that prolonged HPA axis dysregulation due to bullying experiences may lead to increased high risk for psychosis among individuals with 22q.

Individuals with 22q deletion syndrome are one example of a special needs population that report high rates of ID, medical, and neurodevelopmental impairments that may be at increased risk for bullying involvement. Specifically, most individuals with 22q struggle with social and interpersonal situations due to poor social cognition (e.g., theory of mind, interpretation of social cues), emotional recognition, processing speed, and verbal reasoning (Goldenberg et al., 2012; Jalbrzikowski et al., 2012). While individuals with 22q have been described to have age-expected levels of social interest and motivation, they are generally far less socially competent then their same-aged peers; instead, some are more successful at making and maintaining friendships with developmentally-matched peers who are chronologically younger (Angkustsiri et al., 2014; Norkett et al., 2017). Due to co-occurring genetically-mediated developmental, physical, and learning difficulties, youth with 22q are more likely to negatively stand out among their peers (Angkustsiri et al., 2012; Jalbrzikowski et al., 2015; Jonas et al., 2014; Niarchou, Martin, Thapar, Owen, & van den Bree, 2015; Tunnard et al., 2014). The occurrence of borderline cognitive abilities and poor interpretation of social situations may result in poor social competence and elevated risk for being a target of bullying victimization (Angkustsiri et al., 2014; L. E. Campbell et al., 2015).

5.2. Bullying and psychosis risk

Longstanding bullying victimization has been associated with negative psychological development and may contribute to the development of serious mental illness such as psychosis. A history of bullying victimization has been linked to an increase in psychosis symptoms, particularly symptoms of suspiciousness or paranoia in individuals with established psychotic illnesses (Shakoor et al., 2015; Trotta et al., 2013; Valmaggia et al., 2015). Additionally, studies indicate that increased severity and duration of bullying victimization were significantly associated with the emergence of psychosis symptoms in clinical high-risk (CHR) individuals (Addington et al., 2013; Bebbington et al., 2004; Schreier et al., 2009; Van Dam et al., 2012). An examination of individual symptoms demonstrated a trend with regards to clinical suspicion, showing elevated endorsements symptoms of suspiciousness in individuals with a reported history of bullying victimization in both CHR and TD individuals (Valmaggia et al., 2015). Researchers have hypothesized that this increase in symptoms in TD, CHR, and clinical symptomatic populations may be attributed to maladaptive behaviours and negative coping styles learned during the sensitive period of adolescent development. Indeed, a study found that internalizing problems mediated the relationship between bullying victimization and psychosis symptoms (Fisher et al., 2013). Individuals who reported having negative attributional styles and endorsed a history of bullying victimization were more likely to find supporting evidence for their hostile and threatening views of the world (Shakoor et al., 2015). Additionally, early psychotic experiences may mediate the relationship between bullying and adulthood psychosis symptoms (Wolke et al., 2014). Though not all individuals who experience trauma are expected to develop such psychotic-like experiences, however, an individual’s risk increases as a result of their environmental, as well as genetic, factors. Overall, while most of the current research suggests that bullying victimization is associated with increased risk for developing psychosis symptoms during adolescence and later adulthood (Shakoor et al., 2015; Trotta et al., 2013), some studies have failed to confirm this relationship (Bentall et al., 2012). However, it is important to note that the impact of bullying does not simply attenuate over time, and that it can have negative long-term effects on mental health status.

6. Conclusion

Stress and anxiety are known factors that contribute to onset of serious mental illness and have been linked to the development of psychosis in 22q (Beaton and Simon, 2010). Due to the genetic vulnerability for psychosis and its potential interaction with stress that exists in the 22q population, it is essential to further explore the impact of both bullying perpetration and victimization among youth with 22q and its potential role in the development of psychosis symptoms. Due to the high risk for psychosis in youth with 22q, the careful and ongoing assessment of daily stress and anxiety is important. While not everyone with 22q and or who has experienced bullying is expected to develop any lifetime symptoms of psychosis, it is important to carefully monitor when bullying occurs due to the cascade of negative physical and mental health outcomes that goes along with bullying perpetration and victimization.

Acknowledgements

Funding for the current study was supported by the NIH Grant Project #3R01MH107108.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.04.011.

References

- Addington J, Stowkowy J, Cadenhead KS, Cornblatt BA, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, … Cannon TD, 2013. Early traumatic experiences in those at clinical high risk for psychosis. E. Interv. Psychiatr 7 (3), 300–305. 10.1111/eip.12020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angkustsiri K, Goodlin-Jones B, Deprey L, Brahmbhatt K, Harris S, Simon TJ, 2014. Social impairments in chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2ds): autism spectrum disorder or a different endophenotype? J. Autism Dev. Disord 44(4), 739–746. 10.1007/s10803-013-1920-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angkustsiri K, Leckliter I, Tartaglia N, Beaton EA, Enriquez J, Simon TJ, 2012. An examination of the relationship of anxiety and intelligence to adaptive functioning in children with chromosome 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr.: JDBP (J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr.) 33 (9), 713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arseneault L, Bowes L, Shakoor S, 2010. Bullying victimization in youths and mental health problems: ‘much ado about nothing’? Psychol. Med 40 (5), 717–729. 10.1017/S0033291709991383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arseneault L, Walsh E, Trzesniewski K, Newcombe R, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, 2006. Bullying victimization uniquely contributes to adjustment problems in young children: a nationally representative cohort study. Peds 118 (1), 130–138. 10.1542/peds.2005-2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashford CD, Ashcroft K, Maguire N, 2012. Emotions, traits and negative beliefs as possible mediators in the relationship between childhood experiences of being bullied and paranoid thinking in a non-clinical sample. J. Exp. Psychopatho 3 (4), 624–638. 10.1001/archpedi.161.1.78. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes J, Belsky J, Broomfield KA, Melhuish E, 2006. Neighbourhood deprivation, school disorder and academic achievement in primary schools in deprived communities in England. Int. J. Behav. Dev 30 (2), 127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Beaton EA, Simon TJ, 2010. How might stress contribute to increased risk for schizophrenia in children with chromosome 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome?. J. Neurodev. Disord 3 (1), 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington PE, Bhugra D, Brugha T, Singleton N, Farrell M, Jenkins R, … Meltzer H, 2004. Psychosis, victimisation and childhood disadvantage. Br. J. Psychiatry 185(3), 220–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejerot S, Plenty S, Humble A, Humble MB, 2013. Poor motor skills: a risk marker for bully victimization. Aggress. Behav 39 (6), 453–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentall RP, Wickham S, Shevlin M, Varese F, 2012. Do specific early-life adversities lead to specific symptoms of psychosis? A study from the 2007 the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Schizophr. Bull 38 (4), 734–740. 10.1093/schbul/sbs049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger KS, 2007. Update on bullying at school: science forgotten? Dev. Rev 27 (1), 90–126. [Google Scholar]

- Blake JJ, Lund EM, Zhou Q, Kwok O. m., Benz MR, 2012. National prevalence rates of bully victimization among students with disabilities in the United States. Sch. Psychol. Q 27 (4), 210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botto LD, May K, Fernhoff PM, Correa A, Coleman K, Rasmussen SA, … Elixson EM, 2003. A population-based study of the 22q11. 2 deletion: phenotype, incidence, and contribution to major birth defects in the population. Peds 112 (1), 101–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LE, McCabe KL, Melville JL, Strutt PA, Schall U, 2015. Social cognition dysfunction in adolescents with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (velo-cardio-facial syndrome): relationship with executive functioning and social competence/functioning. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res 59 (9), 845–859. 10.1111/jir.12183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell ML, Morrison AP, 2007. The relationship between bullying, psychotic-like experiences and appraisals in 14–16-year olds. Behav. Res. Ther 45 (7), 1579–1591. 10.1016/j.brat.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss6304a1.htm, Accessed date: 28 September 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016. Understanding Bullying Fact Sheet https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/Bullying_Factsheet.pdf, Accessed date: 28 September 2017.

- Cook CR, Williams KR, Guerra NG, Kim T, 2009. Variability in the prevalence of bullying and victimization In: Jimerson SR, Swearer SM, Espelage DL (Eds.), Handbook of Bullying in Schools: an International Perspective Routledge, New York, pp. 347–362. [Google Scholar]

- De Loore E, Drukker M, Gunther N, Feron F, Deboutte D, Sabbe B, … Myin-Germeys I, 2007. Childhood negative experiences and subclinical psychosis in adolescence: a longitudinal general population study. E. Interv. Psychiatr 1 (2), 201–207. 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2007.00027.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Smedt B, Devriendt K, Fryns JP, Vogels A, Gewillig M, Swillen A, 2007. Intellectual abilities in a large sample of children with Velo-Cardio-Facial Syndrome: an update. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res 51 (Pt 9), 666–670. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2007.00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker MC, Koot HM, 2003. DSM-IV disorders in children with borderline to moderate intellectual disability. I: prevalence and impact. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 42 (8), 915–922. 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046892.27264.1A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Due P, Holstein BE, 2008. Bullying victimization among 13 to 15 year old school children: results from two comparative studies in 66 countries and regions. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 20 (2), 209–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elzinga BM, Roelofs K, Tollenaar MS, Bakvis P, van Pelt J, Spinhoven P, 2008. Diminished cortisol responses to psychosocial stress associated with lifetime adverse events: a study among healthy young subjects. Psychoneuroendocrinology 33 (2), 227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estell DB, Farmer TW, Irvin MJ, Crowther A, Akos P, Boudah DJ, 2009. Students with exceptionalities and the peer group context of bullying and victimization in late elementary school. J. Child Fam. Stud 18 (2), 136–150. 10.1348/0007099041552305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faith MA, Reed G, Heppner CE, Hamill LC, Tarkenton TR, Donewar CW, 2015. Bullying in medically fragile youth: a review of risks, protective factors, and recommendations for medical providers. J. Dev. and Behav. Peds 36 (4), 285–301. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, Hamby SL, 2015. Prevalence of childhood exposure to violence, crime, and abuse: results from the national survey of children’s exposure to violence. JAMA Peds 169 (8), 746–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher H, Schreier A, Zammit S, Maughan B, Munafò MR, Lewis G, Wolke D, 2013. Pathways between childhood victimization and psychosis-like symptoms in the ALSPAC birth cohort. Schizophr. Bull 39 (5), 111 10.1007/s00127-009-0171-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gini G, 2008. Associations between bullying behaviour, psychosomatic complaints, emotional and behavioural problems. J. Peds. and Child Health 44 (9), 492–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg PC, Calkins ME, Richard J, McDonald-McGinn D, Zackai E, Mitra N, … Kohler C, 2012. Computerized neurocognitive profile in young people with 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome compared to youths with schizophrenia and At-Risk for psychosis. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B: Neuropsychiatr. Gen 159 (1), 87–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothelf D, 2014. Measuring prodromal symptoms in youth with developmental disabilities: a lesson from 22q11 deletion syndrome. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 53 (9), 945–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothelf D, Feinstein C, Thompson T, Gu E, Penniman L, Van Stone E, … Reiss A, 2007. Risk factors for the emergence of psychotic disorders in adolescents with 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome. Am. J. Psychiatry 164 (4), 663–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grati FR, Molina Gomes D, Ferreira JC, Dupont C, Alesi V, Gouas L, Vialard F, 2015. Prevalence of recurrent pathogenic microdeletions and microduplications in over 9500 pregnancies. Prenat. Diagn 35 (8), 801–809. 10.1002/pd.4613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt MK, Vivolo-Kantor AM, Polanin JR, Holland KM, DeGue S, Matjasko JL, … Reid G, 2015. Bullying and Suicidal Ideation and Behaviors: a Meta-Analysis. Peds 2014–1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter SC, Durkin K, Boyle JM, Booth JN, Rasmussen S, 2014. Adolescent bullying and sleep difficulties. Eur. J. Psychol 10 (4), 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Jalbrzikowski M, Carter C, Senturk D, Chow C, Hopkins JM, Green MF, … Bearden CE, 2012. Social cognition in 22q11.2 microdeletion syndrome: relevance to psychosis. Schizophr. Res 142 (0), 99–107. 10.1016/j.schres.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalbrzikowski M, Lazaro MT, Gao F, Huang A, Chow C, Geschwind DH, … Bearden CE, 2015. Transcriptome profiling of peripheral blood in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome reveals functional pathways related to psychosis and autism spectrum disorder. PLoS One 10 (7), e0132542 10.1371/journal.pone.0132542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas RK, Montojo CA, Bearden CE, 2014. The 22q11.2 deletion syndrome as a window into complex neuropsychiatric disorders over the lifespan. Biol. Psychiatry 75 (5), 351–360. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher I, Harley M, Lynch F, Arseneault L, Fitzpatrick C, Cannon M, 2008. Associations between childhood trauma, bullying and psychotic symptoms among a school-based adolescent sample. Br. J. Psychiatry 193 (5), 378–382. 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.049536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher I, Keeley H, Corcoran P, Ramsay H, Wasserman C, Carli V, … Cannon M, 2013. Childhood trauma and psychosis in a prospective cohort study: cause, effect, and directionality. Am. J. Psychiatry 170 (7), 734–741. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12091169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lataster T, van Os J, Drukker M, Henquet C, Feron F, Gunther N, Myin-Germeys I, 2006. Childhood victimisation and developmental expression of non-clinical delusional ideation and hallucinatory experiences: victimisation and non-clinical psychotic experiences. Soc. Psychiatr. Epidemiol 41 (6), 423–428. 10.1007/s00127-006-0060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessne D, Yanez C, 2016. Student Reports of Bullying and Cyber-Bullying: Results from the 2015 School Crime Supplement to the National Crime Victimization Survey. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2017/2017015.pdf, Accessed date: 1 October 2017.

- Lupien SJ, Fiocco A, Wan N, Maheu F, Lord C, Schramek T, Tu MT, 2005. Stress hormones and human memory function across the lifespan. Psychoneuroendocrinology 30 (3), 225–242. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maïano C, Aimé A, Salvas M-C, Morin AJ, Normand CL, 2016. Prevalence and correlates of bullying perpetration and victimization among school-aged youth with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. Res. Dev. Disabil 49, 181–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo D, Corey S, Kelly L, Yohannes S, Youngquist A, Stuart B, … Loewy R, 2017. The role of trauma and stressful life events among individuals at clinical-high risk for psychosis: a review. Front. Psychiatry 8 (55). 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, 2014. The brain on stress: the good and the bad In: Popoli M, Diamond D, Sanacora G (Eds.), Synaptic Stress and Pathogenesis of Neuropsychiatric Disorders Springer, New York, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin C, Byers R, Vaughn R, 2010. Responding to Bullying Among Children with Special Educational Needs And/or Disabilities Anti-Bullying Alliance, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Nansel TR, Craig W, Overpeck MD, Saluja G, Ruan WJ, 2004. Cross-national consistency in the relationship between bullying behaviors and psychosocial adjustment. Arch. Peds. & Adol. Med 158 (8), 730–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P, 2001. Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. J. Am. Med. Assoc 285 (16), 2094–2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, E., and Medicine, 2016. Preventing Bullying through Science, Policy, and Practice National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niarchou M, Martin J, Thapar A, Owen MJ, van den Bree M, 2015. The clinical presentation of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children with 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatr. Gen 168 (8), 730–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norkett EM, Lincoln SH, Gonzalez-Heydrich J, D’Angelo EJ, 2017. Social cognitive impairment in 22q11 deletion syndrome: A review. Psychiatry Res 253, 99–106. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein KH, Dawson ME, 1984. A heuristic vulnerability/stress model of schizophrenic episodes. Schizophr. Bull 10 (2), 300–312 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D, 1993. Bullying at School: what We Know and what We Can Do Blackwell Publishing, Malden. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D, 2001. Peer harassment: a critical analysis and some important issues In: Juvonen J, Graham S (Eds.), Peer Harassment in School. Guilford Publications, New York, pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D, Limber S, Mihalic S, 1999. Blueprints for Violence Prevention, Book Nine: Bullying Prevention Program Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence, Boulder, CO. [Google Scholar]

- Pittet I, Berchtold A, Akré C, Michaud P-A, Suris J-C, 2010. Are adolescents with chronic conditions particularly at risk for bullying? Arch. Dis. Child 95 (9), 711–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford L, Corral S, Bradley C, Fisher HL, 2013. The prevalence and impact of child maltreatment and other types of victimization in the UK: findings from a population survey of caregivers, children and young people and young adults. Child Abuse Negl 37 (10), 801–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose CA, Espelage DL, Monda-Amaya LE, Shogren KA, Aragon SR, 2015. Bullying and middle school students with and without specific learning disabilities: an examination of social-ecological predictors. J. Learn. Disabil 48 (3), 239–254. 10.1177/0022219413496279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose CA, Monda-Amaya LE, 2011. Bullying and victimization among students with disabilities: effective strategies for classroom teachers. Interv. Sch. Clin 48 (2), 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Rose CA, Monda-Amaya LE, Espelage DL, 2011. Bullying perpetration and victimization in special education: a review of the literature. Remedial Special Educ 32 (2), 114–130. [Google Scholar]

- Behavior in 22q11.2 Deletion, S.,Schneider M, Debbané M, Bassett AS, Chow EWC, Fung WLA, van den Bree MBM, 2014. Psychiatric disorders from childhood to adulthood in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: results from the international consortium on brain and behavior in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Am. J. Psychiatry 171 (6), 627–639. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreier A, Wolke D, Thomas K, Horwood J, Hollis C, Gunnell D, … Harrison G, 2009. Prospective study of peer victimization in childhood and psychotic symptoms in a nonclinical population at age 12 years. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr 66 (5), 527–536. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrooten I, Scholte RHJ, Cillessen AHN, Hymel S, 2016. Participant roles in bullying among Dutch adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol 1–14. 10.1080/15374416.2016.1138411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakoor S, McGuire P, Cardno AG, Freeman D, Plomin R, Ronald A, 2015. A shared genetic propensity underlies experiences of bullying victimization in late childhood and self-rated paranoid thinking in adolescence. Schizophr. Bull 41 (3), 754–763. 10.1093/schbul/sbu142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, Cicchetti D, 2001. Parental maltreatment and emotion dysregulation as risk factors for bullying and victimization in middle childhood. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol 30 (3), 349–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shprintzen RJ, 2008. Velo-cardio-facial syndrome: 30 years of study. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev 14 (1), 3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solberg ME, Olweus D, 2003. Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus bully/victim questionnaire. Aggress. Behav 29 (3), 239–268. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard J, Niendam T, Hendren R, Carter C, Simon TJ, 2010. Attenuated positive symptoms of psychosis in adolescents with chromosome 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome. Schizophr. Res 118 (1), 118–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang SX, James JY, Moore TM, Calkins ME, Kohler CG, Whinna DA, … Emanuel BS, 2014. Subthreshold psychotic symptoms in 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 53 (9), 991–1000 e1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson D, Whitney I, Smith PK, 1994. Bullying of children with special needs in mainstream schools. Support Learn 9 (3), 103–106. 10.1111/j.1467-9604.1994.tb00168.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trotta A, Di Forti M, Mondelli V, Dazzan P, Pariante C, David A, … Fisher HL, 2013. Prevalence of bullying victimisation amongst first-episode psychosis patients and unaffected controls. Schizophr. Res 150 (1), 169–175. 10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunnard C, Rane LJ, Wooderson SC, Markopoulou K, Poon L, Fekadu A, … Cleare AJ, 2014. The impact of childhood adversity on suicidality and clinical course in treatment-resistant depression. J. Affect. Disord 152–154, 122–130. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undheim AM, Sund AM, 2010. Prevalence of bullying and aggressive behavior and their relationship to mental health problems among 12-to 15-year-old Norwegian adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 19 (11), 803–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt T, McDougall P, Hymel S, Sunderani S, 2009. The relationship between power and bullying behavior In: Jimerson SR, Swearer SM, Espelage DL (Eds.), Handbook of Bullying in Schools: an International Perspective Routledge, New York, pp. 211–222. [Google Scholar]

- Valmaggia LR, Day FL, Kroll J, Laing J, Byrne M, Fusar-Poli P, McGuire P, 2015. Bullying victimisation and paranoid ideation in people at ultra high risk for psychosis. Schizophr. Res 10.1016/j.schres.2015.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam D, Van Der Ven E, Velthorst E, Selten J, Morgan C, De Haan L, 2012. Childhood bullying and the association with psychosis in non-clinical and clinical samples: a review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med 42 (12), 2463–2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Roekel E, Scholte RH, Didden R, 2010. Bullying among adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence and perception. J. Autism Dev. Disord 40 (1), 63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney I, Nabuzoka D, Smith PK, 1992. Bullying in schools: mainstream and special needs. Support Learn 7 (1), 3–7. 10.1111/j.1467-9604.1992.tb00445.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams NM, Owens MJ, 2004. Genetic abnormalities of chromosome 22 and the development of psychosis. Curr. Psychiatry Rep 6 (3), 176–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolke D, Lereya ST, Fisher HL, Lewis G, Zammit S, 2014. Bullying in elementary school and psychotic experiences at 18 years: a longitudinal, population-based cohort study. Psychol. Med 44 (10), 2199–2211. 10.1017/S0033291713002912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodin M, Wang PP, Aleman D, McDonald-McGinn D, Zackai E, Moss E, 2001. Neuropsychological profile of children and adolescents with the 22q11.2 micro-deletion. Genet. Med 3 (1), 34–39 doi: 10.109700125817-200101000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang GS, McLoyd VC, 2015. Do parenting and family characteristics moderate the relation between peer victimization and antisocial behavior? A 5-year longitudinal study. Soc. Dev 24 (4), 748–765. [Google Scholar]

- Yi JJ, Tang SX, McDonald-McGinn DM, Calkins ME, Whinna DA, Souders MC, … Gur RC, 2014. Contribution of congenital heart disease to neuropsychiatric outcome in school-age children with 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B: Neuropsychiatri. Gen 165 (2), 137–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubin J, Spring B, 1977. Vulnerability: a new view of schizophrenia. J. Abnorm. Psychol 86 (2), 103–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]