Abstract

Alopecia areata (AA) is a common autoimmune disease, with a lifetime risk of ~2%. In AA, the immune systems targets the hair follicle, resulting in clinical hair loss. AA prognosis is unpredictable, and currently there is no definitive treatment. Our previous whole genome expression studies identified active immune circuits in AA lesions, including common γ-chain cytokine and IFN pathways. Since these pathways are mediated through JAK kinases, we prioritized clinical exploration of small molecule JAK inhibitors. In preclinical trials in mice, tofacitinib successfully prevented AA development and reversed established disease. In our tofacitinib trial in 12 patients with moderate to severe AA, 11 patients completed a full course of treatment with minimal adverse events. Following limited response to the initial dose (5mg BID), the dose was escalated (10mg BID) for nonresponding subjects. Eight of 12 patients demonstrated ≥50% hair regrowth while 3 patients demonstrated <50% hair regrowth as measured by SALT score. One patient demonstrated no regrowth. Gene expression profiles and Alopecia Areata Disease Activity Index (ALADIN) scores correlated with clinical response. Our open label studies of ruxolitinib and tofacitinib have shown dramatic clinical responses in moderate-to-severe AA, providing strong rationale for larger clinical trials using JAK inhibitors in AA.

INTRODUCTION

AA is a common autoimmune disease, with a lifetime risk of approximately 2%, affecting an estimated 5.3 million individuals in the US (Safavi et al), (McMichael et al). Persistent moderate/severe AA causes significant disfigurement and psychological distress to affected individuals (Colon et al). Clinical development of innovative therapies in AA has lagged far behind other autoimmune conditions.

Alopecia areata results from autoimmune attack on the hair follicles. Using comparative genomics of the transcriptional profiles of skin from both AA model mice, and humans with AA, we have found that cytotoxic CD8 (+) NKG2D (+) T cells are both necessary and sufficient for the induction of AA in mouse models of disease. On the basis of our preclinical findings (Xing et al), we initiated a Phase 2 efficacy signal-seeking clinical trial in moderate to severe AA, assessing the clinical and immunopathological response to treatment with oral tofacitinib, a JAK 1,3 inhibitor which also inhibits JAK 2. Presently, tofacitinib is FDA-approved for the treatment of adult patients with moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and is under study for many other autoimmune conditions (Schwartz et al). Tofacitinib has been shown to prevent the onset of, and reverse, AA in the C3H-HeJ animal model of AA. Thus far, several studies have demonstrated clinical efficacy of oral tofacitinib in treating patients with AA (Jabbari et al) or AU (alopecia universalis) (Kennedy et al), (Liu et al). In all reported cases, clinical response was achieved with minimal or no adverse events.

RESULTS

Primary Efficacy Endpoint

This study was an open-label, clinical trial to investigate tofacitinib 5 mg to 10 mg PO twice daily in the treatment of moderate/severe AA.

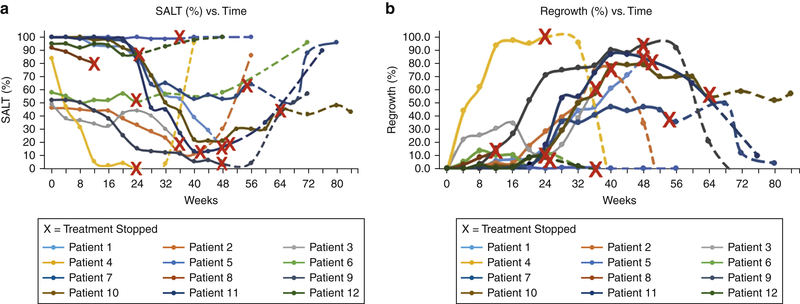

Eight out of twelve patients met the study’s primary efficacy endpoint of 50% or greater hair re-growth from baseline as assessed by SALT index at the end of treatment. The duration of treatment ranged from 6 to 18 months, at the discretion of the investigator and dependent on the individual subject’s response as well as safety considerations. The length of time from baseline for patients to reach primary efficacy endpoint was on average 32 weeks, with the time period ranging from as little as 8 weeks to as much as 64 weeks (Figure 1), (Figure 2), (Table 1).

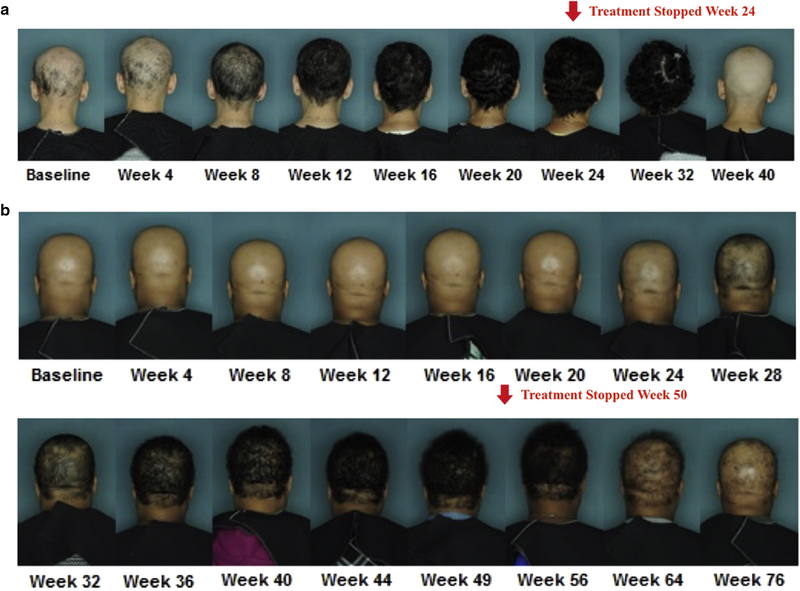

Figure 1. Clinical progression of therapeutic response to Tofacitinib and relapse after discontinuation.

(a) Relapse after treatment was stopped on week 24. (b) Relapse after treatment was stopped on week 50.

Figure 2. Severity of alopecia tool (SALT) scores for individual patients.

(a) during treatment (solid lines) and following cessation of (dashed lines) tofacitinib treatment. An “X” corresponding to each respective patient line indicates time at which treatment was stopped. In the event of a patient dropping out of the study prior to tofacitinib discontinuation or being lost to follow up, the “X” is placed at the end of the patient line. (b) Percentage regrowth for individual patients during and following cessation of tofacitinib treatment.

Table 1.

Characteristics of enrolled patients and treatment course outcomes.

| Patient # | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 52 | 29 | 18 | 40 | 31 | 37 | 36 | 46 | 26 | 24 | 37 | 40 |

| Sex | F | F | M | F | M | M | F | F | F | M | F | F |

| Race | Caucasian | Caucasian | Hispanic | Caucasian | African | African | Hispanic | African | Hispanic | Caucasian | African | Caucasian |

| Duration of current episode of scalp hair loss | 3 years | 1 year | 2 years | 4 years | 30 years | 33–34 years | 10 years | 3 years | 2–3 years | 1 year | 5 years | 20 years |

| Total duration patiant has had alopecia areata | 3 years | 7 years | 3 years | 5 years | 30 years | 33–34 years | 17 years | 20 years | 20 years | 4 years | 16 years | 33 years |

| Total duration of AT/AU (if patient has AT/AU) | 1 year | N/A | N/A | N/A | 30 years | N/A | 6 years | n/a | n/a | 1 year | 4 years | n/a |

| Weeks of dose escelation(s) | 20,28 | 20,32 | 26,32 | N/A | 18,26 | 16 | 12,20 | n/a | 8,16 | 8,16 | 4,12 | 5,12 |

| Week treatment was stopped | 48 | 41 | 38 | 24 | 36 | 24 | 54 | 12 | 48 | 64 | 50 | 25 |

| Baseline SALT (%) score | 100 | 46 | 49 | 84 | 100 | 58 | 100 | 92 | 52 | 100 | 100 | 95 |

| Lowest SALT (%) score achieved | 15 | 11 | 19 | 0 | 99 | 50 | 50 | 80 | 3 | 21 | 13 | 86.5 |

| Week lowest SALT (%) score was achieved | 48 | 40 | 36 | 24 | 20 | 24 | 68 | 12 | 48 | 44 | 40 | 20 |

| Greatest regrowth percentage of SALT (%) score achieved | 85.0 | 76.1 | 61.2 | 100.0 | 1.0 | 13.8 | 50.0 | 13.0 | 94.2 | 79.0 | 87.0 | 8.9 |

| Patient outcome | Responder, Dropped out | Responder | Responder, lost to follow up | Responder | Nonresponder | Nonresponder | Responder | Dropped out | Responder | Responder | Responder | Nonresponder |

| Clinical durability of response * | N/a | 7 weeks | N/a | 8–16 weeks | N/a | N/a | 14 weeks | N/a | 8–16 weeks | 24 weeks | 10–26 weeks | N/a |

| Absolute durability of response** | N/a | 7–15 weeks | N/a | 8–16 weeks | N/a | N/a | 22 weeks | N/a | 16 weeks | 24 weeks | 26 weeks | N/a |

Clinical durability of response is defined as the minimum observed time a responder maintained 50% regrowth after the treatment drug has been discontinued. This accounts for the amount of durability that is clinically significant as it only considers duration in which a patient would still quality as a “responder” upon discontinuation of drug.

Absolute durability of response is defined as the minimum observed time a responder maintained a SALT score that was below the patients’ baseline SALT score after the treatment drug has been discontinued. In some cases, there is a range of dates which reflect that this was an outcome that occurred while the patient was between visits.

Four out of the five patients with either AT or AU successfully achieved 50% or greater response in hair regrowth. All patients who had reached the study’s primary efficacy endpoint, with the exception of one patient, failed to respond to lower doses, in some cases despite prolonged treatment, but responded with onset of regrowth within 4 weeks of initiation of the higher dose of tofacitinib, at 10 mg BID.

Secondary Efficacy Outcomes

As secondary endpoints, efficacy was measured by changes in hair re-growth as a continuous variable as determined by physical exam and Canfield photography, as well as patient and physician global evaluation scores.

Global overall improvement in SALT score at end of treatment

Eleven out of twelve patients attained a global overall improvement in SALT score at the end of treatment with results ranging from 12.1% to 100% regrowth, with an average 56.8% regrowth. Baseline SALT scores for the twelve patients ranged from 46% to 100% and at the end of treatment SALT scores ranged from 0% to 99%. The average baseline SALT score of 81.3% decreased to 40.8% at the end of treatment. Only one subject had no response to the study medication after 36 weeks of administration, having experienced a negligible decrease in SALT score with approximately 1% hair regrowth that consisted of 0.5–1mm depigmented fine terminal hairs throughout the scalp and facial area. Vellus hair growth was not used in SALT score calculations. No patients experienced worsening of AA from baseline at the time of treatment discontinuation, with eleven patients exhibiting varying degrees of hair regrowth.

Time to Regrowth of Scalp and Body Hair

Regrowth was seen in responders as soon as four weeks after the effective dose of study medication was initiated. All twelve patients, experienced between 0 and less than 25% of hair regrowth by week 4 as assessed by physician global assessment (PGA), a static evaluation of scalp regrowth rated as “worse”, “same”, or “improved”. The degrees to which hair regrowth presented itself at 4 weeks were highly varied and individual responses ranged from less than 1% with the introduction of few fine terminal hairs to at most approximately 45% regrowth with depigmented and pigmented, terminal and fine terminal hairs. Three patients displayed mild shedding of scalp hair while on tofacitinib, but at end of treatment, remained improved compared to baseline.

All 12 enrolled patients exhibited varying degrees of body hair regrowth. Regrowth of body hair was documented as soon as four weeks after effective dose of study medication was initiated. Body hair regrowth was mixed, with some patients experiencing minimal to full facial hair regrowth, including eyelashes and eyebrows. Other areas of body hair regrowth noted in patients included the arms, legs, axillary and groin area.

Durability of Responses

To assess the durability of responses, patients who achieved 50% regrowth from baseline during the first 6 to 18 months, were followed for an additional 6 months off treatment or until it was determined that relapse had occurred. Of the eight patients who achieved 50% regrowth, one patient dropped out of the observation period in order to continue the medication outside of the study. Of the seven patients who were followed observationally, six patients exhibited variable hair shedding after completion of the study treatment, with two patients showing initial signs of shedding approximately 3–4 weeks after end of treatment, and four patients showing initial signs of shedding approximately 8 weeks after end of treatment. Hair shedding was initially slight, but accelerated at 4–6 months off tofacitinib. The final patient did not exhibit any hair shedding throughout the observational period (24 weeks / 6 months off tofacitinib). Excellent durability of response was seen in three out of the eight responders, maintaining lower SALT scores as compared to baseline SALT scores at nearly 24 weeks off tofacitinib. Four patients experienced worsening of AA compared to baseline at the conclusion of the study at nearly 24 weeks off the study medication. Shedding of body hair coincided with the timeline of scalp hair loss.

Overall, eleven out of the twelve patients who were initially enrolled in this study completed the intended 24 to 72 weeks of study treatment. One patient underwent early termination of the study treatment at week 12 due to experiencing hypertensive urgency as an adverse event.

Change in Patient Quality of Life Assessment

Change in patient quality of life assessment was compared from baseline to selected visits during the treatment period (Weeks 12 and 24). Quality of life measures were based on changes in the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) (Basra et al). Seven out of the twelve patients experienced a decrease in their DLQI score as measured from baseline to week 24 (see table 4). The mean baseline DLQI score of 6.5 ± 5 decreased to 5.2 ± 6.7 at 3 months of treatment and later increased to 6 ± 6.9 at the end of 6 months of treatment.

Differences in regrowth between patients with patch type AA vs patients with alopecia totalis or universalis

At the end of treatment, the five subjects who were either AT or AU had experienced hair regrowth ranging from 1.0% to 84%, with an average of 52.2% regrowth. This is in comparison to subjects with moderate to severe patchy AA who at the end of treatment, experienced hair regrowth ranging from 12.1% to 100%, with an average 52.1% regrowth. Overall, patients with either patch type AA or AT or AU had, on average, very similar percentage hair regrowth at the end of study treatment. Given the small sample of these patients, it is not known if the observation of similar regrowth rates among AA, AT, and AU patients will continue to hold in future studies.

Biomarker and Clinical Correlative Studies

Gene expression profiling was performed on skin biopsies taken at baseline and up to 24 weeks of treatment, with additional optional biopsies performed if indicated by clinical considerations.

We applied both naïve and supervised clustering to this dataset in order to assess two features: the overall molecular effect of tofacitinib treatment on patient samples, and the concordant molecular response of the disease. The former was assessed by an unbiased, unsupervised differential expression analysis and the latter was measured by response to previously published gene expression signatures defining AA pathology. To ensure parity of the data, for this analysis we only included patient samples that had matched pre-treatment, Tx-00, and 24 weeks of treatment, Tx-24, samples.

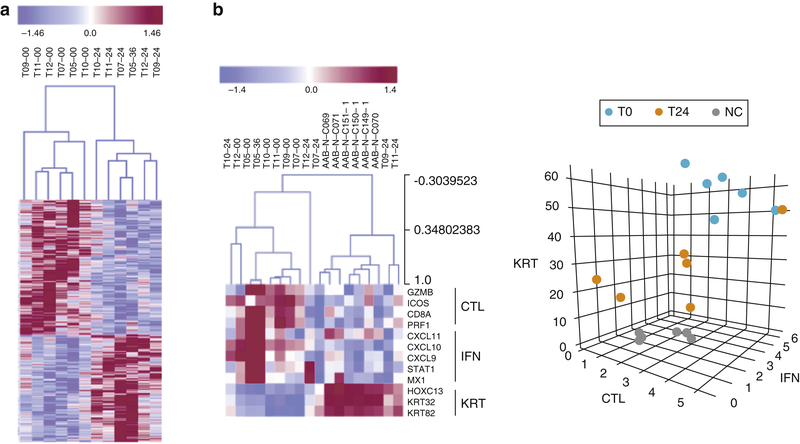

Figure 3A represents the overall molecular impact of tofacitinib treatments observed in the patient biopsies. Molecular response in this instance was defined as molecular divergence between patient samples taken at pre-treatment and >24 weeks of treatment. Unsupervised clustering was able to produce a biomarker panel that robustly segregated pre- and post-treatment samples with no cross-over in the clustering (4A dendrogram). The gene list that comprises this signature is available in supplemental data.

Figure 3. Molecular analysis of skin biopsies taken from patients during a clinical trial of tofacitinib citrate.

(a) 24 weeks of treatment corresponds with significant shifts in molecular profile of scalp biopsies. (b). ALADIN signature scoring accurately predicts and reflects response to treatment using a disease signature.

These molecular effects coincide with significant shifts in ALADIN score in most patients (4B heatmap). In this instance, unaffected control patient biopsies were included as a reference, (indicated as AAB-N-Cx). All initial patient biopsies cluster away from unaffected controls using ALADIN. Treated patient samples that cluster with the control samples indicate significant suppression of AA molecular pathology and suggest response to tofacitinib, while patient samples that remain clustered with pre-treated samples suggest resistance or recalcitrance to treatment. This is more simply represented in the 3D ALADIN plot. Prior to treatment, patients start at a steady-state with significant distance from healthy, unaffected samples (T0 vs NC, normal control). During treatment, patients that respond will shift in this space towards the NC samples (T24). One patient (a clinical nonresponder) showed virtually no molecular shift following treatment (T0 and T24 datapoints are proximal to each other). The pharmacodynamic reduction in ALADIN score during treatment in the favorable responders and lack thereof in the patients in whom there was little or no clinical response, confirm the utility of the ALADIN scores as a physiological relevant dynamic biomarker that positively correlates with clinical response.

Adverse Events

In this study, an Adverse Event (AE) is defined as any new untoward medical occurrence or worsening of a pre-existing medical condition in a patient or clinical investigation subject administered an investigational (medicinal) product and may or may not have a causal relationship with this treatment. Specific frequencies for adverse events are noted in (Table 2). Of note, tofacitinib was discontinued for 1 patient with a history of hypertension who experience a hypertensive urgency while on the study medication.

Table 2.

Adverse events of patient enrolled differentiated by severity of adverse event grade.

| Adverse Event | Any Grade | Grade 3–4 |

|---|---|---|

| Upper resperatory infection | 11 (91.6%) | 0 |

| Increased bowel movement frequency | 4 (33.3%) | 0 |

| Blood on Urinalysis | 4 (33.3%) | |

| Loose stools | 3 (25%) | 0 |

| Mild acne | 3 (25%) | 0 |

| Weight Gain | 2 (16.6%) | 0 |

| Asymptomatic bacteriuria | 2 (16.6%) | |

| Hypertensive Urgency | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| Bloating | 1 (8.3%) | 0 |

| Constipation | 1 (8.3%) | 0 |

| Dizziness | 1 (8.3%) | 0 |

| Headache | 1 (8.3%) | 0 |

| Neuropathic pain | 1 (8.3%) | 0 |

| Vaginal spotting (post menopause) | 1 (8.3%) | 0 |

| Conjunctivitis | 1 (8.3%) | 0 |

| Urinary Retention | 1 (8.3%) | 0 |

| Transaminitis | 1 (8.3%) | 0 |

Clinical laboratory evaluation was performed on all subjects during the screening period, at baseline and as otherwise deemed necessary to monitor for abnormal values and for normalization of those values. Clinical laboratory evaluation consisted of complete blood count, basic metabolic profile, hepatic panel and urinalysis with microscopic exam, hepatitis B and C screening panel, HIV test, fasting lipid profile, TB and serum pregnancy test for women of child bearing potential. No patient met protocol-defined clinical laboratory discontinuation criteria. Overall, there were no major abnormalities in laboratory evaluations. The laboratory adverse events that were observed are listed in Table 2. Notably, tofacitinib was discontinued for 1 patient after experiencing persistent 1+ blood on urinalysis. The patients primary care doctor was concerned and requested that we discontinue the study drug.

Discussion

Tofacitinib is known to effectively treat rheumatoid arthritis by modulating the interferon response inflammatory pathway by inhibition of JAK1/JAK3 (Keisuke et al). AA and RA share the same interferon-gamma response pathway, which provided the rationale for selecting tofacitinib for evaluation in AA (Xing et al). Already, tofacitinib has been shown to prevent the onset of, and reverse, AA in the C3H-HeJ animal model of AA (Xing et al).

Tofacitinib was effective in achieving a global overall improvement in SALT score at the end of treatment for eleven out of twelve patients. The effective dose for the majority of responders was 10mg BID. Only 1 subject had a full response to 5mg BID. In contrast to previous work on this subject (Kennedy et al) the majority of our patients did not respond to 5mg BID after at least 1 month of therapy. Some patients remained on 5mg BID for 4 to 6 months prior to dose escalation yet had absolutely no hair growth. However, once the dose was increased to 10mg BID, regrowth onset was seen within one month. Further studies are needed to explore the difference in response between our studies versus prior reported studies. Baseline SALT scores for the twelve patients ranged from 46% to 100% and at the end of treatment SALT scores ranged from 0% to 99%. The mean baseline SALT score of 81.3% decreased to 40.8% at the end of treatment. Overall, patients with either patch type AA, or AT or AU had on average very similar percentage hair regrowth at the end of study treatment. This suggests that the severity of disease may not be the determining factor for response versus no response. It may be possible that a long duration of current episode of AA decreases the probability of therapeutic response, but based on our observations longer duration of disease does not appear to preclude response to therapy.

Tofacitinib was well tolerated in all twelve patients. One patient discontinued the study due to hypertension. There were no reported serious adverse events. Observed adverse effects were infrequent and clinical laboratory abnormalities were uncommon. This study adds to the existing literature supporting the potential of Janus kinase inhibitors to halt hair loss and allow regrowth in some patients with alopecia areata. Although this therapy is not a cure, as evidenced by relapse of hair loss after treatment ended, tofacitinib may potentially be a therapeutic option for the treatment of hair loss in some AA patients. Further work is needed to elucidate optimal treatment strategies for maintenance of response and minimization of risks. Limitations in this study consist of those inherent in an open label study. This includes observer bias as a result of physicians and study participants being un-blinded during treatment. To limit this bias, objective tools, such as SALT scoring, and photography were used to measure the primary and secondary efficacy of treatment. Another limitation of this study is the small sample size. This decreases the study’s external validity and as a result may not be generalizable to the population of interest i.e. patients with moderate to severe AA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design, Oversight, and Participants

The study was conceived and conducted by the investigative team at Columbia University. This study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice (GCP), as defined by the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) and in accordance with the ethical principles underlying European Union Directive 2001/20/EC and the United States Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21, Part 50 (21CFR50). Monitoring for regulatory compliance and adherence to the IRB approved protocol was performed by the Columbia University Clinical Trials Office and the Department of Surgery Regulatory Team. The study was registered on clinicaltrials.gov prior to initiation. IRB approval was granted for all experiments performed in this study and written informed patient consent was obtained for all experiments, procedures, and treatments involved in this study. In addition, permission was granted from patients for the publication of their photographs. This was an open-label pilot study of tofacitinib 5mg BID to 10mg orally BID, for 6 to 18 months in the treatment of moderate to severe AA, and AT or AU, followed by 6 months follow-up off drug to assess for delayed response to treatment and/or the incidence and timing of recurrence of disease. The initial treatment dose was tofacitinib 5mg PO BID for at least 1 month, which was increased to 10mg + 5mg QD for at least 1 month, and then to 10mg PO BID if the patient had absence of any terminal hair regrowth on the scalp. End of treatment was defined as at least 6–12 months on a dose that appeared to be having a positive response i.e. an effective dose or ending of treatment if no regrowth occurred within 3 months of the highest tolerable dose, and at least 6 months total tofacitinib treatment. A full course of treatment was defined as at least 6–12 months on a dose that appeared to be having a positive response i.e. an effective dose or ending of treatment if no regrowth occurred within 3 months of the highest tolerable dose and at least 6 months total tofacitinib treatment. We enrolled 12 adult patients, including 7 patients with moderate to severe AA (30–95% hair loss) and 5 patients with alopecia totalis (AT) or AU.

Study Assessments and Outcomes

The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of responders at the end of treatment, (6 to 18 months of treatment), with response defined as 50% or greater hair re-growth from baseline as assessed by the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score, a standardized, validated method for estimating hair loss in AA (Olsen et al). Secondary efficacy endpoints included hair re-growth as a continuous variable as determined by physical exam and Canfield photography, as well as patient and physician global evaluation scores. Additionally, Quality of Life measures (Dermatology Quality of Life Index – DLQI) were done at regular pre-specified intervals. To assess the durability of responses, patients were followed for an additional 6 months after treatment was completed. Additionally, safety analysis was included as a secondary endpoint for all subjects who received at least one dose of tofacitinib and was monitored at monthly visits.

Biomarker Studies

We were able to accurately recapitulate the molecular assessment of patient recovery during treatment (see figure 3) using gene expression and the ALADIN signature. Moreover, we were able to leverage this data to construct biomarkers corresponding to patient response to treatment and tofacitinib mechanism-of-action (MoA) (see figure 3). Rather than being derived from the pathogenic definitions of the disease, this signature is specifically derived to measure patients’ individual molecular responses in their scalp skin biopsies as a function of tofacitinib treatment over time, facilitated by the sequential time points. Statistically significant overlap of this signature and the pathogenic signature provides a quantitative framework for the a priori prediction of drug efficacy (Petukhova et al). Furthermore, these quantitative molecular profiles can be used to define the molecular regulatory mechanism of response to tofacitinib using network analysis (Chen et al), (Margolin et al), and to predict non-responders a priori - patients that exhibit low phenotypic response to treatment also show incomplete or impartial molecular response based on the tofacitinib MoA exhibited in responder patients, (see figure 3).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by a grant from the AA Initiatives – Gates Foundation and the Locks of Love Foundation. Photographic equipment was provided by Canfield Scientific, Inc. Ali Jabbari is supported by the NIH/NIAMS (K08AR0691110). Columbia SDRC (NIAMS P30AR044535) Cores were extensively utilized.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Columbia University has filed patent applications around the use of JAK inhibitors in alopecia areata, which have been licensed to Aclaris Therapeutics, Inc. R.C., J.M.W. and A.M.C. are consultants to Aclaris Therapeutics, Inc. A.M.C. has received grant support from Pfizer, Inc (unrelated to the context of this trial).

This work was supported in part by a grant from the AA Initiatives – Gates Foundation and the Locks of Love Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Clinical trials registration number: NCT02299297

REFERENCES

- Basra MK, Fenech R, Gatt RM, Salek MS, Finlay AY. The Dermatology Life Quality Index 1994–2007: a comprehensive review of validation data and clinical results. Br J Dermatol 2008;159:997–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JC, Alvarez MJ, Talos F, et al. Identification of causal genetic drivers of human disease through systems-level analysis of regulatory networks. Cell 2014;159:402–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colon EA, Popkin MK, Callies AL, Dessert NJ, Hordinsky MK. Lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with alopecia areata. Comprehensive psychiatry 1991;32:245–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabbari A, Nguyen N, Cerise JE, et al. Treatment of an alopecia areata patient with tofacitinib results in regrowth of hair and changes in serum and skin biomarkers. Exp Dermatol 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeshima Keisuke, Yamaoka Kunihiro,Kubo Satoshi, et al. The jak inhibitor tofacitinib regulates synovitis through inhibition of interferon-gamma and interleukin-17 production by human CD4+ T cellsArthritis Rheum, 64 (2012), pp. 1790–1798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy Crispin M, Ko JM, Craiglow BG, et al. Safety and efficacy of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib citrate in patients with alopecia areata. JCI Insight. 2016;22:1(15):e89776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu LY, Craiglow BG, Dai F, King BA. Tofacitinib for the treatment of severe alopecia areata and variants: a study of 90 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(1):22–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin AA, Nemenman I, Basso K, et al. ARACNE: an algorithm for the reconstruction of gene regulatory networks in a mammalian cellular context. BMC bioinformatics 2006;7 Suppl 1:S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMichael AJ, Pearce DJ, Wasserman D, et al. Alopecia in the United States: outpatient utilization and common prescribing patterns. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2007;57:S49–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen EA, Hordinsky MK, Price VH, et al. Alopecia areata investigational assessment guidelines--Part II. National Alopecia Areata Foundation. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2004;51:440–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petukhova L, Cabral RM, Mackay-Wiggan J, Clynes R, Christiano AM. The genetics of alopecia areata: What’s new and how will it help our patients? Dermatologic therapy 2011;24:326–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safavi KH, Muller SA, Suman VJ, Moshell AN, Melton LJ, 3rd. Incidence of alopecia areata in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1975 through 1989. Mayo Clinic proceedings 1995;70:628–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz DM, Bonelli M, Gadina M, O’Shea JJ. Type I/II cytokines, JAKs, and new strategies for treating autoimmune diseases. Nature reviews Rheumatology 2016;12:25–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing L, Dai Z, Jabbari A, et al. Alopecia areata is driven by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and is reversed by JAK inhibition. Nature medicine 2014;20:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.