Abstract

Background:

Women represent 23% of all Americans living with HIV. By 2020, more than 70% of Americans living with HIV are expected to be 50 and older.

Setting:

This study was conducted in the Southern US – a geographic region with the highest number of new HIV infections and deaths.

Objective:

To explore the moderating effect of age on everyday discrimination; group-based medical distrust; enacted, anticipated, internalized HIV stigma; depressive symptoms; HIV disclosure; engagement in care; antiretroviral medication adherence; and quality of life among women living with HIV.

Methods:

We used multi-group structural equation modeling to analyze baseline data from 123 participants enrolled at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill site of the Women’s Interagency HIV Study during October 2013 - May 2015.

Results:

Although age did not moderate the pathways hypothesized, age had a direct effect on internalized stigma and quality of life. Everyday discrimination had a direct effect on anticipated stigma and depressive symptoms. Group-based medical distrust had a direct effect on depressive symptoms and a mediated effect through internalized stigma. Internalized stigma was the only form of stigma directly related to disclosure. Depressive symptoms was a significant mediator between group-based medical distrust, everyday discrimination, and internalized stigma reducing ART medication adherence, engagement in care, and quality of life.

Conclusions:

Everyday discrimination, group-based medical distrust, and internalized stigma adversely affect depressive symptoms, ART medication adherence, and engagement in care, which collectively influence the quality of life of women living with HIV.

Keywords: women living with HIV, discrimination, stigma, medical distrust, adherence, quality of life, depression

Introduction

In the United States (US), the lifetime risk of acquiring HIV among women varies by race, ethnicity, and geography. While white women have a 1 in 880 lifetime risk, the lifetime risk is 1 in 48 for African American women and 1 in 227 for Hispanic women/Latinas.1 Overall, women represent 23% of all Americans living with HIV.2 Geographically, the Southern US has the highest number of new HIV infections and deaths; further, in comparison to the rest of the nation, the quality of HIV prevention, care and treatment in this region varies.3 Eight of the 10 states and the 10 metropolitan statistical areas with the highest rates of new HIV diagnoses are in the South.3 Poverty, conservative social values, an excess burden of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and lack of access to primary healthcare are common in this region.3–4 Additionally, with its historical legacies and institutional policies promoting discrimination, exacerbating HIV stigma and fear, as well as denying equal opportunities, inequities in life and health outcomes are significant.4

Because of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and other scientific advances, persons living with HIV (PLWH) now have a longer life expectancy and will age with HIV as a co-morbid condition.5 Older persons, defined age 50 and older, comprise an estimated 45% of currently diagnosed PLWH in the US.6 By 2020, more than 70% of Americans living with HIV are expected to be 50 and older.7 The quality of life of aging PLWH may be diminished due to loneliness and isolation associated with illness and/or previous loss of family and friends; co-morbidities and medical complications; polypharmacy; poorer mental health; and stigma and discrimination from healthcare providers and society.5–8

Once considered unidimensional, HIV stigma is now recognized as a multidimensional construct with multiple mechanisms of action. In the HIV Stigma Framework by Earnshaw and Chaudoir9, the mechanisms of HIV stigma include enacted, anticipated, and internalized forms. Turan and colleagues10 conceptualized four forms of HIV stigma -- enacted, anticipated, community (perceived), and internalized – that are layered upon structural and intersectional stigmas (race, class, gender, sexuality), which in turn influence engagement in care.

PLWH directly experience enacted HIV stigma through discrimination, stereotyping, and/or prejudice by others because of their HIV status.11 Anticipated HIV stigma is reflected in the person’s concerns about discrimination or adverse events that might happen should one’s HIV status become known by others – whether a consequence of intentional or planned disclosure, or inadvertent disclosure through breaches in confidentiality.12 Perceived or community stigma relates to how much a PLWH believes that the public stigmatizes someone with HIV.13 Internalized HIV stigma, also referred to as self-stigma, occurs when the negative attitudes, beliefs, and feelings associated with HIV become integrated into self – threatening self-concept and self-esteem.14–16 The mechanisms of action associated with HIV stigma are a barrier to prevention, treatment, disclosure, engagement in care, and adherence among PLWH.17

WLWH tend to experience more negative effects of HIV stigma than men.18–19 Among women, those reporting higher levels of HIV stigma frequently have higher levels of stress and depressive symptoms,20–21 are less likely to receive medical care for HIV21–22 and adhere to ART,23–24 and frequently report a lower quality of life.21, 25 However, little is known about how older PLWH, especially WLWH, experience the various forms of HIV stigma compared to their younger counterparts. 26. In a meta-analysis of 24 studies conducted in PLWH in North America, Logie and Gadalla27 found a negative relationship between age and stigma. This study was limited by the substantial variability in how HIV stigma was measured, the small number of WLWH in the samples, and data collection periods of more than a decade ago (2000 to 2007). In recent work by Emlet and colleagues26, PLWH 55 and older had significantly lower overall and internalized stigma compared to PLWH under 40, even with controlling for gender, sexual orientation, income, time since diagnosis, depression, maladaptive coping, and social support. When controlling for demographic and psychosocial variables, this study found that age did not predict enacted or anticipated stigma. However, there was a significant interaction between depression and age suggesting that stigma declines with age among those who are depressed but increases to age 50 and then decreases in older age groups among those without depression.

In a random US national sample, Kessler and colleagues28 documented that 60.9% of participants reported day-to-day exposure to discrimination. The construct of everyday discrimination describes aspects of interpersonal discrimination that are sometimes relatively minor, can be chronic or episodic, but are common.29 These frequent instances of unfair treatment adversely impact the health of individuals being discriminated against – both physically and mentally.29 Likely related to prior discrimination in the healthcare setting, group-based medical distrust – the tendency not to trust the medical system and its personnel – is also associated with negative health outcomes.30 In the US, group-based medical distrust, especially related to race and/or ethnicity, is a significant mediator of ART medication adherence among PLWH31–32 and is associated with sub-optimal HIV healthcare utilization among WLWH.33 When medical trust is high, PLWH are more engaged in self-care.34 Consequently, experiences of discrimination and medical distrust impair patient-provider relationships, negatively influencing engagement in care,13 and adherence to ART.31–32

In PLWH over the age of 50, especially WLWH, there has been minimal exploration of the moderating effect of age on the multidimensional mechanisms associated with HIV stigma and its interaction with depressive symptoms and health outcomes, ART medication adherence, and engagement in care.3, 26 Further, research exploring the intersection of experiences with everyday discrimination, group-based medical distrust, and the mechanisms of action of HIV stigma among WLWH in the Southern US is limited.3 Thus, a theoretical understanding of the relationships among these phenomena will facilitate development of effective interventions to help WLWH successfully age, engage in care, and adhere to ART while optimizing quality of life.

Guided by empirical evidence and presented in graphic form, theory synthesis allows representation of factors preceded or influenced by a particular factor or set of factors, represent the effects that occur after an event, and put discrete scientific data into a more theoretically organized representation.35 Therefore, building upon the theoretical work of Earnshaw and Chaudoir9 and Turan and colleagues10, this study aimed to explore the theoretical pathways, and the moderating effect of age, among group-based medical distrust [GBM], experiences with everyday discrimination [EVD], HIV stigma (enacted [ENA], anticipated [ANT], internalized [INT]), depressive symptoms [DEP], HIV disclosure [DIS], engagement in care [ENG], ART medication adherence [ADH], and quality of life [QOL] among WLWH.

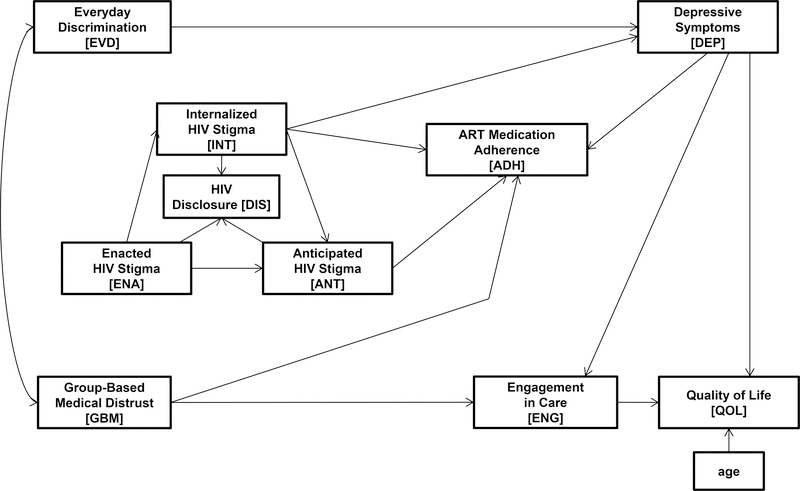

In the proposed theoretical model (figure 1), we hypothesized that EVD and GBM, as independent exogenous variables, had a non-directional association. EVD was hypothesized to be directly associated with DEP while GBM was hypothesized to be directly associated with both ADH and ENG. Treating HIV stigma as a multidimensional construct, we hypothesized that ENA would directly influence INT and ANT. In turn, INT would directly influence DEP while INT and ANT would directly influence ADH. INT, ENA, and ANT were hypothesized to have a direct effect on DIS. DEP, preceded by INTL and EVD, was hypothesized to decrease ENG, ADH, and QOL. Similarly, ENG, preceded by GBM and DEP was hypothesized to negatively influence QOL. The goal of the analysis was to explore these theoretical relationships and identify the most parsimonious model which yielded robust fit indices.

Figure 1.

The hypothesized structural equation model.

Methodology

We analyzed screening and baseline data from WLWH who enrolled at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) site of the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) between October 2013 and May 2015. The WIHS is a multicenter, prospective, observational study of women who are either living with HIV or at risk for HIV acquisition; the first enrollment wave occurred in 1994.36 Reflecting the significant HIV disease burden in the Southern US, four new sites – including UNC – were added during the most recent WIHS participant expansion in 2013. WLWH were eligible to enroll in the WIHS if they were between the ages of 25–60, consented to participate in the study, complete the interview in English or Spanish, travel to the research site for an interview and physical examination every six months, and have blood drawn for laboratory testing.36–37

Human subjects’ approval for the WIHS was obtained from the UNC Office of Human Research Ethics; in addition, this study was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board. The constructs associated with the specific aim of this study were measured using psychometrically reliable and valid instruments and are described in Table I.29–30, 38–42

Table I.

Variable Descriptions and Pearson Correlation Coefficients among the Variables in the Final Model (N = 123 Women).

| Variable [abbreviation] Measurement Instrument (psychometric properties) Range; psychometric properties |

EVD | GBM | ENA | INT | ANT | DEP | ENG | ADH | DIS | QOL | Women < 50 Years of Age (n = 90) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | ||||||||||||

|

Everyday Discrimination [EVD]

Everyday Discrimination Scale29 (α=0.88) Range: 10 (high) - 40 (low) |

.40** | .17 | .06 | .30** | .45** | −.21* | −.14 | .08 | −.43** | 16.08 | 6.44 | ||

|

Group Based Medical Distrust [GBM]

Group-Based Medical Distrust Scale30 (α=0.88) Range: 12 (high) - 60 (low) |

.29 | .06 | .08 | .10 | .33** | −.41** | −.12 | −.08 | −.24* | 27.06 | 7.80 | ||

|

HIV Stigma – Enacted [ENA]

HIV-Related Enacted Stigma Scale38 (α=0.95) Range: 11 (low) - 44 (high) |

.29 | .33 | .44** | .43** | .31** | −.08 | −.13 | −.04 | −.17 | 23.43 | 6.85 | ||

|

HIV Stigma – Internalized [INT]

HIV-Related Internalized Stigma Scale38 (α=0.88) Range: 7 (low) - 28 (high) |

.21 | .71** | .58** | .35** | .27* | −.20 | −.25* | −.21* | −.26* | 16.44 | 4.33 | ||

|

HIV Stigma – Anticipated [ANT]

HIV-Related Anticipated Stigma Scale38 (α=0.86) Range: 6 (low) - 24 (high) |

.28 | .16 | .44* | .46** | .19 | .03 | −.10 | −.07 | −.12 | 17.30 | 3.95 | ||

|

Depressive Symptoms [DEP]

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale39 (α=0.85–.90) Range: 0 (low) - 60 (high) |

.21 | .47** | .11 | .60** | .34 | −.32** | −.33** | −.07 | −.65** | 15.23 | 11.22 | ||

|

Engagement in Care [ENG]

Healthcare Utilization Scale41 (α=0.71) Range: 0 (poor/inappropriate) - 4 (high/appropriate) |

−.19 | −.23 | .05 | −.39* | −.12 | −.42* | .12 | .14 | .40** | 2.98 | 1.07 | ||

|

Medication Adherence [ADH]

Medication Adherence Self-Report for HIV Care40 (α=0.80) Range: 0% - 100% adherence/30 days |

.01 | −.12 | −.11 | −.05 | .05 | −.31 | −.03 | .03 | .20 | 90.56 | 8.94 | ||

|

HIV Disclosure [DIS]

HIV Disclosure Scale41 Range: 0 (no disclosure) - 8 (high level) |

−.13 | −.33 | −.37* | −.54** | −.55** | −.31 | .12 | .04 | .05 | 3.36 | 1.57 | ||

|

Quality of Life [QOL]

Brief Health Status Assessment Instrument42 (α=0.78– 0.85) Range: 1 (low) - 100 (high) |

−.18 | −.22 | −.12 | −.45** | −.21 | −.77** | .50** | .15 | .06 | 68.27 | 20.73 | ||

| Women ≥ 50 Years of Age (n = 33) | M | 14.64 | 26.48 | 22.66 | 14.63 | 15.93 | 14.06 | 3.09 | 92.93 | 3.36 | 65.43 | ||

| SD | 5.78 | 6.87 | 7.79 | 5.51 | 3.45 | 10.94 | 1.13 | 13.56 | 1.32 | 23.42 | |||

Notes. Values to the right of the black boxes, shaded in gray, are the correlation coefficients for women age < 50 years of age and values to the left of the black boxes are the correlation coefficients for women ≥ 50 years of age. M = Mean. SD = Standard Deviation.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

Analytically, the moderating effects of age were tested for invariance of the pathways (Figure 1) across the two age groups (WLWH >50 years vs. < 50 years) using multi-group structural equation modeling (MG-SEM).43 In MG-SEM, equality constraints were imposed on the pathways and the data for both groups were analyzed simultaneously to obtain efficient estimates.44 In the unconstrained model, the pathways were allowed to vary across the two age groups. The nested chi-square (χ2) test statistic was used to compare the fit between these two models. If a better model fit were obtained from the unconstrained model, it would suggest that the pathways are moderated by age; in other words, the strength of the pathways among the variables in the model was different across the two age groups. Bootstrapping was implemented to address the issue of unstable standard error estimation resulting from the small sample.45 The effect sizes, instead of p-values, were reported as the standardized regression coefficients of the pathways which assess the strengths of relationships as hypothesized in the structural equation model tested in this study (see figure 1).

Results

A total of 123 WLWH enrolled in the UNC WIHS site. The mean age of the women was 43.29 years (SD = 9.24) with 26.8% (n=33) of the women being aged 50 or older. Most of the women were non-white (75.6% were African American, 8.9% Hispanic/Latina and 2.4% Native American/Alaskan Native). Approximately 35% of the women had less than a high school (HS) education and another 35% had completed HS or earned a HS equivalent; the remaining 30% had some college education or possessed an undergraduate or higher degree. Less than half of women were legally married, in a common law marriage, or were living with a partner (43.4%), while 34. 4% had never married. Most (81.2%) had an annual household income of $24,000 or less and 58.5% were unemployed at the time of WIHS enrollment.

WLWH of all ages experienced high levels of everyday discrimination. On the instrument used to measure this construct, the Everyday Discrimination Scale29, the possible scores range between 10 and 40 with lower scores illustrating higher discrimination. Among WLWH under 50 and among those 50 or older, their respective mean scores were 16.08 (SD = 6.44) and 14.64 (SD = 5.78). Similarly, WLWH had moderately high levels of medical distrust as measured by the Group-Based Medical Distrust Scale30 (range of 12 to 60 with lower scores representing higher levels of distrust). The mean score among WLWH under 50 was 27.06 (SD = 7.80), while the mean score among WLWH 50 or older was 26.48 (SD = 6.87). Please see Table I for more information.

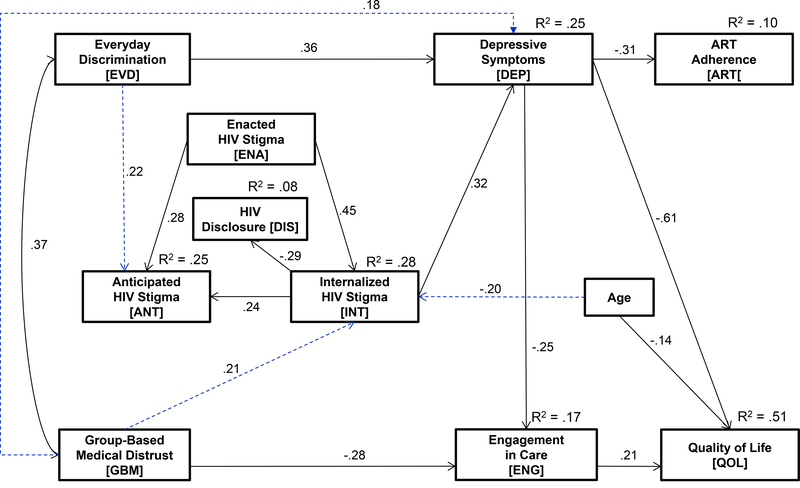

Using IBM SPSS AMOS version 23.0,46 the proposed specified model, as illustrated in Figure 1, was tested using MG-SEM. The proposed specified model converged during initial estimation, but several pathways were non-significant (INT-ADH, ANT-DIS, ANT-ADH, ENC-DIS, and GBM-ADH. Using the modification index (MI), a stepwise model generation strategy was then employed deleting the non-significant parameters and introducing substantively meaningful and justifiable pathways (both recursive and non-recursive) to improve goodness of fit.7; the new pathways introduced, beyond those originally hypothesized, are indicated in blue in figure 2. Ultimately, a final fitted parsimonious model (figure 2) with more satisfactory and robust fit indices (χ2 = 35.00, df = 39, p = .653; Goodness of Fit Index [GFI] = .95; Normed Fit Index [NFI] = .89; Incremental Fit Index [IFI] = 1.01; Relative Fit Index [RFI] = .84; Comparative Fit Index [CFI] = 1.00; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation [RMSEA] < .001) was identified.

Figure 2. The final fitted structural equation model with stigma as a multidimensional construct.

Fit Indices for Model: X2 = 35.004, df = 39, p = .653; X2/df = .898

GFI = .951; NFI = .889; IFI = 1.014; RFI = .843; CFI = 1.000; RMSEA = .000 [90% CI = .000 – 0.53]

Note: Dotted pathways indicated in blue were newly identified during stepwise model generation.

This fitted model was then utilized to determine the moderating effect of age on the identified model. Using MG-SEM, age was not identified as a moderator of the proposed pathways (Δχ2 = 8.22, Δdf = 9, p = .513). Instead, age was directly related to quality of life (β = −0.14, p < .031) and internalized HIV stigma (β = −0.20, p < .010) in the total sample. Further, the independent exogenous variables, everyday discrimination and group-based medical mistrust, were correlated (r = .37, p < .016). These two variables influenced depressive symptoms with everyday discrimination having a direct effect (β = 0.36, p < .014), and group-based medical mistrust having an indirect, or mediated effect, through internalized stigma (α×β = 0.21×0.32 = 0.07, p < .020). In turn, internalized HIV stigma was directly related to decreased disclosure (β = −0.29, p < .005). Depressive symptoms served as a significant negative mediator of ART medication adherence (α×β = 0.36×(−0.31) = −0.11, p < . 011), engagement in care (α×β = 0.36×(−0.25) = −0.09, p < .027), and quality of life (α×β = 0.36×(−0.61) = −0.22, p < .009). Overall, this model predicted 51% of the variance associated with quality of life among the total sample of WLWH.

Discussion

We identified a model that contextualizes the lives of WLWH and the factors influencing their quality of life in the Southern US, a region where HIV poses a significant burden. Although age did not moderate the pathways among the variables as hypothesized, increased age had a direct and negative effect on internalized HIV stigma and quality of life. Depressive symptoms were a significant mediator in the identified model mediating the paths between everyday discrimination and ART medication adherence; the path between group-based medical distrust-internalized HIV stigma, and group-based medical distrust and ART medication adherence. In turn, depressive symptoms had a direct and negative effect on engagement in care and quality of life.

As an increased number of WLWH will age in the coming years, it is essential to understand the contextual factors that influence elements of the HIV care continuum and quality of life in this population. WLWH in the US are more likely to be of color and socioeconomically disadvantaged, and frequently experience many layers of discrimination – racism, sexism, ageism, and classism – in their everyday lives. These socially constructed layers of discrimination, referred to as intersectional stigma, may result in multiple stigmatized social positions hindering engagement and retention in care and ART medication adherence and function as powerful stressors.48–52 Subsequently, physiologic responses to these and other stressors, including the mechanisms of action of HIV stigma, negatively impact health in the long term48 and are associated with HIV disease progression and symptoms, decreased CD4 counts, development of AIDS, and an increased risk for mortality.53–55 Understanding how experiences with everyday discrimination relate to health inequities and quality of life among WLWH is critical in order to develop effective interventions.

In this study, experiences with everyday discrimination were also common and directly linked to depressive symptoms, which in turn diminished ART medication adherence, engagement in care, and quality of life. In a study by Casagrande et al56, African Americans and whites who experienced discrimination were more likely to have delays in seeking medical care and poor adherence to medical care recommendations. Among PLWH, discrimination in the healthcare setting was associated with internalized stigma resulting in depressive symptoms which in turn lowered medication adherence.57 Our study did not identify a relationship between experiences with everyday discrimination and of HIV stigma’s mechanisms of action; instead, our results indicated that depressive symptoms served as a mediator between the effects of everyday discrimination and group-based medical distrust and internalized HIV stigma and ART medication adherence, engagement in care, and quality of life.

In a national sample of PLWH, 41% reported at least one discriminatory healthcare experience since HIV diagnosis and 24% did not completely/almost completely trust their healthcare providers.58 Among WLWH, mistrust of providers and the medical community is associated with discrimination and lack of continuation in care.59 Recently, Stringer and colleagues reported that healthcare workers in HIV/sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics in the Deep South had higher levels of stigma towards PLWH compared to those working in non-HIV/STI clinics.60 This is concerning considering the number of WLWH who receive care in these settings. Further, stigma experienced in the health care setting results in internalized stigma and anticipated stigma from health care workers leading to mistrust of physicians.61 Although a patient-provider relationship built on trust is critical, such relationships take time to develop.

Among this sample of WLWH, mean scores associated with HIV stigma, and its mechanisms of action, were high. Consequently, women were less likely to disclose their status to others. diminishing their potential to obtain social support, engage in intimate relationships, and negotiate safer sex with partners. Across studies, HIV stigma, especially internalized stigma, is associated with depressive symptoms and lower levels of adherence as was identified in this group of WLWH.62–65 Concurrent with the gender inequities for depression in the general population, WLWH have higher rates of depression than men with HIV66 reinforcing the need for screening and referral for treatment, when identified. Further, HIV stigma continues to be a source of shame for many older African American WLWH who consequently avoid treatment for HIV because it might “out” them or because they did not like being isolated in an HIV clinic or the “infectious disease clinic”.59 These results help to shed light on why WLWH who experience chronic depression are nearly twice as likely to die from AIDS-related complications compared to those with little or no depression, even after controlling for diminishing health over time.66

Several studies have explored different types of stigma and their impact on various psychosocial outcomes and adherence. In these studies, the detrimental impact of perceived stigma by the community, experienced stigma in the community, and perceived discrimination in the healthcare setting were linked to lower self-esteem 61, 67 diminished social support,61 and sub-optimal ART medication adherence 67 with internalized stigma being a common mediator. Additionally, several studies have examined the mediators between internalized stigma and diminished ART medication adherence identifying visit adherence68, social support/loneliness69, depressive symptoms69, adherence self-efficacy70, attachment-related anxiety71, and concern about being seen taking HIV medications70–71 as mediators. Further, economic security mediated the relationship between HIV stigma and racial discrimination and physical quality of life among a national cohort of WLWH in Canada; however, economic security did not mediate the relationship between HIV stigma and mental quality of life or between gender discrimination and mental or physical quality of life.49 Thus, future studies need to consider these recently identified mediators between various forms of HIV stigma, especially internalized stigma, and psychosocial outcomes and elements of the HIV care continuum.

The strengths of this study include the use of psychometrically sound instruments enabling the exploration of experiences with everyday discrimination and group-based medical mistrust and their intersection with enacted, anticipated and internalized HIV stigma, elements of the treatment cascade, and quality of life. By treating HIV stigma as a multidimensional construct in the analysis, we were able to specifically examine how multiple types of stigma – enacted, anticipated, and internalized – rather than a unidimensional construct, were related to other constructs in the identified model. Further, the method of analysis – MG-SEM – allowed exploration of complex mediated pathways and the moderating effect of age.

This study is limited by a small non-probability sample potentially impacting covariances, parameter estimates, and testing of model fit as well as reducing generalizability of results. Further, the omission of important variables associated with care and treatment outcomes (e.g., time since diagnosis, availability of transportation, type of employment) also limit this study. Although this sample was representative of WLWH in the US regarding race and ethnicity, multisite studies that are racially and ethnically representative including women from urban and rural environments and from across the age continuum are needed. Further, WLWH who have higher levels of group-based medical distrust and/or HIV stigma may have been less likely to participate in a research study like WIHS. Like all cross-sectional studies, we were not able to determine the exact nature of relationships in the final identified model; thus, longitudinal research designs are critically needed to explore the trajectories of HIV stigma, experiences with everyday discrimination, and the patient-provider relationship, and their connections to ART medication adherence, engagement in care, depressive symptoms, and quality of life over time. Finally, the construct engagement in care was focused on healthcare in general and not specifically HIV-oriented medical care. As WLWH age, the likelihood of experiencing medical complications, co-morbidities, and polypharmacy increases; therefore, it is critical that engagement in primary and HIV-oriented medical care as well as utilization patterns be explored in future research.

Public Health Implications

Everyday discrimination, group-based medical distrust, and internalized HIV stigma adversely affect depressive symptoms, ART medication adherence, and engagement in care, which collectively influence quality of life. Interventions are needed to combat these important contextual factors and their clinical and psychosocial effects on the lives of WLWH.

Acknowledgments

Source of Support

This research was supported in part by the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR, P30 NR014139-04S1 PD: Michael Relf; NINR, P30 NR014139S/Sharron Docherty and Donald. E. Bailey, PIs). Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), U01-AI-10339 (Adaora Adimora). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The WIHS is funded primarily by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), with additional co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH). Targeted supplemental funding for specific projects is also provided by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health. WIHS data collection is also supported by P30-AI-050410 (UNC CFAR).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors have a conflict of interest to declare associated with this study.

Contributor Information

Michael V. Relf, School of Nursing & Research Professor, Duke Global Health Institute, Duke University, Durham, NC.

Wei Pan, School of Nursing, Duke University, Durham, NC.

Andrew Edmonds, Department of Epidemiology The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Catalina Ramirez, Women’s Interagency HIV Study, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Sathya Amarasekara, School of Nursing, Duke University, Durham, NC.

Adaora A. Adimora, School of Medicine & Professor of Epidemiology, Gillings School of Global Public Health The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lifetime risk of HIV diagnosis in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention web site. http://www.justfacts.com/document/lifetime_risk_hiv.pdf. Published February 2016. Accessed February 11, 2019.

- 2.HIV among women. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention web site. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women/index.html. Updated November 17, 2017 Accessed February 11, 2019.

- 3.HIV in the Southern United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention web site. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies/cdc-hiv-in-the-south-issue-brief.pdf. Updated May 2016 Accessed February 11, 2019.

- 4.Reif S, Safley D, McAllaster C, Wilson E, Whetten K. State of HIV in the US Deep South. J Community Health. 2017. October;42(5):844–853. doi: 10.1007/s10900-017-0325-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office of AIDS Working Group on HIV and Aging. HIV and Aging: State of Knowledge and Areas of Critical Need for Research: A report to the NIH Office of AIDS Research by the HIV and Aging Working Group. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012. July 1; 60(Suppl 1):S1–18. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825a3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.HIV among people aged 50 and older. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) web site.https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/olderamericans/index.html. Updated September 18, 2018. Accessed February 11, 2019.

- 7.National HIV/AIDS and Aging Awareness Day Sept. 18. American Psychological Association (APA) website. https://www.apa.org/pi/aids/resources/aging-awareness.aspx. Accessed February 11, 2019.

- 8.Grov C, Golub SA, Parsons JT, Brennan M, Karpiak SE. Loneliness and HIV-related stigma explain depression among older HIV-positive adults. AIDS Care. 2010. May;22(5):630–9. doi: 10.1080/09540120903280901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Earnshaw VA & Chaudoir SR. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS Behav. 2009. December;13(6):1160–77. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9593-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turan B, Hatcher AM, Weiser SD, Johnson MO, Rice WS, Turan JM. Framing mechanisms linking HIV-related stigma, adherence to reatment, and health outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2017. June;107(6):863–869. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herek GM, Glunt EK. An epidemic of stigma. Public reactions to AIDS. Am Psychol. 1988. November;43(11):886–91. 10.1037/0003-066X.43.11.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Amico KR, Copenhaver MM.HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: a test of the HIV stigma framework. AIDS Behav. 2013. June;17(5):1785–95. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0437-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derlega VJ, Winstead BA, Greene K, Serovich J, Elwood WN. Perceived HIV-related stigma and HIV disclosure to relationship partners after finding out about the seropositive diagnosis. J Health Psychol. 2002. July;7(4):415–32. doi: 10.1177/1359105302007004330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cloete A, Mthembu PP, Mkhonta RN, Ginindza T. Measuring AIDS stigmas in people living with HIV/AIDS: the Internalized AIDS-Related Stigma Scale. AIDS Care. 2009. January;21(1):87–93. doi: 10.1080/09540120802032627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sayles JN, Hays RD, Sarkisian CA, Mahajan AP, Spritzer KL, Cunningham WE. Development and psychometric assessment of a multidimensional measure of internalized HIV stigma in a sample of HIV-positive adults. AIDS Behav. 2008. September;12(5):748–58. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9375-3. Epub 2008 Apr 4. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9375-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Relf MV, Williams M, Barroso J. Voices of Women Facing HIV-Related Stigma in the Deep South. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2015. December;53(12):38–47. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20151020-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The White House Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States: Updated to 2020. Available at: https://files.hiv.gov/s3fs-public/nhas-update.pdf. Accessed February 11, 2019.

- 18.Colbert AM, Kim KH, Sereika SM, Erlen JA. An examination of the relationships among gender, health status, social support, and HIV-related stigma. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2010. Jul-Aug;21(4):302–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez A, Miller CT, Solomon SE, Bunn JY, Cassidy DG. Size matters: community size, HIV stigma, & gender differences. AIDS Behav. 2009. December; 13(6):1205–12. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9465-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whetten K, Reif S, Whetten R, Murphy-McMillan LK. Trauma, mental health, distrust, and stigma among HIV-positive persons: implications for effective care. Psychosom Med. 2008. June;70(5):531–8. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817749dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wingood GM, Diclemente RJ, Mikhail I, McCree DH, Davies SL, Hardin JW, Harris Peterson S, Hook EW, Saag M. HIV discrimination and the health of women living with HIV. Women Health. 2007;46(2–3):99–112. doi: 10.1300/J013v46n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sayles JN, Wong MD, Kinsler JJ, Martins D, Cunningham WE. The association of stigma with self-reported access to medical care and antiretroviral therapy adherence in persons living with HIV/AIDS. J Gen Intern Med. 2009. October;24(10):1101–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1068-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, Wilson MG, Deutsch R, Raeifar E, Rourke SB, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2015. September 3;15:848. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2197-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darlington CK, & Hutson SP. Understanding HIV-related stigma among women in the Southern United States: A literature review. AIDS Behav. 2017. January;21(1):12–26. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1504-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holzemer WL, Human S, Arudo J, Rosa ME, Hamilton MJ, Corless I, Robinson L, Nicholas PK, Wantland DJ, Moezzi S, Willard S, Kirksey K, Portillo C, Sefcik E, Rivero-Méndez M, Maryland M. Exploring HIV stigma and quality of life for persons living with HIV infection. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009. May-Jun;20(3):161–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emlet CA, Brennan DJ, Brennenstuhl S, Rueda S, Hart TA, Rourke SB. The impact of HIV-related stigma on older and younger adults living with HIV disease: does age matter? AIDS Care. 2015;27(4):520–8. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.978734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Logie C, Gadalla TM. Meta-analysis of health and demographic correlates of stigma towards people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2009. June;21(6):742–53. doi: 10.1080/09540120802511877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, & Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. J Health Soc Behav. 1999. September;40(3):208–30. doi: 10.2307/2676349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009. February;32(1):20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-08-185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB, Winkel G, Jandorf L, Redd W. The Group-Based Medical Mistrust Scale: psychometric properties and association with breast cancer screening. Prev Med. 2004. February;38(2):209–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pellowski JA, Price DM, Allen AM, Eaton LA, & Kalichman SC. The differences between medical trust and mistrust and their respective influences on medication beliefs and ART adherence among African-Americans living with HIV. Psychol Health. 2017. September;32(9):1127–1139. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2017.1324969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalichman SC, Eaton L, Kalichman MO, Grebler T, Merely C, & Welles B. Race-based medical mistrust, medication beliefs and HIV treatment adherence: test of a mediation model in people living with HIV/AIDS. J Behav Med. 2016. December;39(6):1056–1064. doi: 10.1007/s10865-016-9767-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sohler NL, Li X, & Cunningham CO. Gender disparities in HIV health care utilization among the severely disadvantaged: can we determine the reasons? AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009. September;23(9):775–83. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gaston GB & Alleyne-Green B. The impact of African Americans’ beliefs about HIV medical care on treatment adherence: a systematic review and recommendations for interventions. AIDS Behav. 2013. January;17(1):31–40. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0323-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker LO & Avant KC. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing (3rd Ed.). 1995; Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Women’s Interagency Study web site. https://statepi.jhsph.edu/wihs/wordpress/. Accessed Febraury 11, 2019.

- 37.Adimora AA, Ramirez C, Benning L, Greenblatt RM, Kempf M-C, Tien PC, Kassaye SG, Anastos K, Cohen M, Minkoff H, Wingood G, Ofotokun I, Fischl MA, Gange S. Cohort profile: The Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS). Int J Epidemiol. 2018. April 1;47(2):393–394i. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bunn JY, Solomon SE, Miller C, Forehand R. Measurement of stigma in people with HIV: a reexamination of the HIV Stigma Scale. AIDS Educ Prev. 2007. June; 19(3):198–208. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.3.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. J Youth Adolesc. 1991;20(2):149–66. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson IB, Fowler FJ, Cosenza CA, Michaud J, Bentkover J, Rana A, Kogelman L & Rogers WH. Cognitive and field testing of a new set of medication adherence self-report items for HIV care. AIDS & Behavior. 2014;18(12):2349–2358. doi: 10.1007/s10461-103-0610-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Women’s Interagency HIV Study. Screening Form. 2013.

- 42.Bozzette SA, Hays RD, Berry SH, Kanouse DE & Wu AW Derivation and properties of a brief health status assessment instrument for use in HIV disease. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;8(3):253–65. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199503010-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed). 2010. New York: Guildford. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Byrne BM. Testing for multigroup invariance using AMOS Graphics: A road less traveled. Structural Equation Modeling: A multidisciplinary journal. 2004;11(20:272–300. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem1102_8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Efron B & Ribshirani RJ. An introduction to the bootstrap. 1998. New York: Chapman and Hall. [Google Scholar]

- 46.International Business Machines (IBM). IBM SPSS AMOS. https://www.ibm.com/us-en/marketplace/structural-equation-modeling-sem.

- 47.MacAllum RH. Model Specification: Procedures, Strategies, and Related Issues In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications (Hoyle RH, Ed.). 1995;Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turan B, Hatcher AM, Weiser SD, Johnson MO, Rice WS, Turan JM. Framing mechanisms linking HIV-related stigma, adherence to treatment, and health outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2017. June;107(6):863–869. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Logie CH, Wang Y, Lacombe-Duncan A, Wagner AC, Kaida A, Conway T, Webster K, de Pokomandy A, Loutfy MR. HIV-related stigma, racial discrimination, and gender discrimination: Pathways to physical and mental health-related quality of life among a national cohort of women living with HIV. Prev Med, 2017. December 22;pii: S0091–7435(17)30505–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.12.018. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Caiola C, Docherty SL, Relf M, Barroso J. Using an intersectional approach to study the impact of social determinants of health for African American mothers living with HIV. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2014. Oct-Dec:37(4):287–98. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Earnshaw VA, Bogart LM, Dovidio JF, Williams DR. Stigma and racial/ethnic HIV disparities: moving toward resilience. Am Psychol;68(4):225–36. doi: 10.1037/a0032705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sangaramoorthy T, Jamison AM, Dyer TV. HIV Stigma, Retention in Care, and Adherence Among Older Black Women Living With HIV. 2017 Jul – Aug; J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2013. May-Jun:28(4):518–531. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Earnshaw VA, Lang SM, Lippitt M, Jin H, Chaudoir SR. HIV stigma and physical health symptoms: do social support, adaptive coping, and/or identity centrality act as resilience resources? AIDS Behav. 2015. January:19(1):41–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0758-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leserman J Role of depression, stress, and trauma in HIV disease progression. Psychosom Med. 2008. June:70(5):539–45. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181777a5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leserman J HIV disease progression: depression, stress, and possible mechanisms. Biol Psychiatry. 2003. August 1 54(3):295–306. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00323-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Casagrande SS, Gary TL, LaVeist TA, Gaskin DJ, Cooper LA. Perceived discrimination and adherence to medical care in a racially integrated community. J Gen Intern Med. 2007. March;22(3):389–95. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0057-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Turan B, Rogers AJ, Rice WS, Atkins GC, Cohen MH, Wilson TE, Adimora AA, Merenstein D, Adedimeji A, Wentz EL, Ofotokun I, Metsch L, Tien PC, Johnson MO, Turan JM, Weiser SD. (2017. December). Association between perceived discrimination in healthcare settings and HIV medication adherence: Mediating psychosocial mechanisms. AIDS Behav;21(12):3431–3439. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1957-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thrasher AD, Earp JA, Golin CE, Zimmer CR. Discrimination, distrust, and racial/ethnic disparities in antiretroviral therapy adherence among a national sample of HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008. September 1;49(1):84–93. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181845589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McDoom MM, Bokhour B, Sullivan M, Drainoni ML. How older black women perceive the effects of stigma and social support on engagement in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015. February;29(2):95–101. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0184. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stringer KL, Turan B, McCormick L, Durojaiye M, Nyblade L, Kempf MC, Lichtenstein B, Turan JM. HIV-related stigma among healthcare providers in the Deep South. AIDS Behav. 2016. January:20(1):115–25. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1256-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kay ES, Rice WS, Crockett KB, Atkins GC, Batey DS, Turan B. Experienced HIV-related stigma in healthcare and community settings: Mediated associations with psychosocial and health outcomes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017. November 13: doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001590. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rueda S, Mitra S, Chen S, Gogolishvili D, Globerman J, Chambers L, Wilson M, Logie CH, Shi Q, Morassaei S, Rourke SB. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: a series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open. 2016. July 13:6(7):e011453. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, Psaros C, Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, Tsai AC. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013. November 13:16(3 Suppl 2):18640. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rao D, Feldman BJ, Fredericksen RJ, Crane PK, Simoni JM, Kitahata MM, Crane. A structural equation model of HIV-related stigma, depressive symptoms, and medication adherence. AIDS Behav. 2012. April:16(3):711–6. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9915-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vyavaharkar M, Moneyham L, Corwin S, Saunders R, Annang L, Tavakoli A. Relationships between stigma, social support, and depression in HIV-infected African American women living in the rural Southeastern United States. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2010. Mar-Apr:21(2):144–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ickovics JR, Hamburger ME, Vlahov D, Schoenbaum EE, Schuman P, Boland RJ, Moore J; HIV Epidemiology Research Study Group. Mortality, CD4 cell count decline, and depressive symptoms among HIV-seropositive women: longitudinal analysis from the HIV Epidemiology Research Study. JAMA. 2001. March 21:285(11):1466–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.11.1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, Browning WR, Raper JL, Mugavero MJ, Turan JM. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav. 2017. January:21(1):283–291. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1451-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rice WS, Crockett KB, Mugavero MJ, Raper JL, Atkins GC, Turan B. Association between internalized HIV-related stigma and HIV care visit adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017. December 15:76(5):482–487. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Turan B, Smith W, Cohen MH, Wilson TE, Adimora AA, Merenstein D, Adedimeji A, Wentz EL, Foster AG, Metsch L, Tien PC, Weiser SD, Turan JM. Mechanisms for the negative effects of internalized HIV-related stigma on antiretroviral therapy adherence in women: The mediating roles of social isolation and depression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016. June 1:72(2):198–205. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Seghatol-Eslami VC, Dark HE, Raper JL, Mugavero MJ, Turan JM, Turan B. Interpersonal and intrapersonal factors as parallel independent mediators in the association between internalized HIV stigma and ART adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017. January 1:74(1):e18–e22. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blake Helms C, Turan JM, Atkins G, Kempf MC, Clay OJ, Raper JL, Mugavero MJ, Turan B. Interpersonal mechanisms contributing to the association between HIV-related internalized stigma and medication adherence. AIDS Behav. 2017. January:21(1):238–247. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1320-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]