Abstract

Previous studies have shown that infusion of a GABAA receptor antagonist, such as bicuculline (bic), into the ventral pallidum (VP) of rats elicits vigorous ingestion in sated subjects and abnormal pivoting movements. Here, we assessed if the ingestive effects generalize to the lateral preoptic area (LPO) and tested both effects for modulation by dopamine receptor signaling. Groups of rats received injections of the dopamine D2 receptor antagonist, haloperidol (hal), the D1 antagonist, SCH-23390 (SCH), or vehicle (veh) followed by infusions of bic or veh into the VP or LPO. Ingestion effects were not observed following LPO bic infusions. Compulsive ingestion associated with VP activation was attenuated by hal, but not SCH. VP bic-elicited pivoting was attenuated by neither hal, nor SCH.

Keywords: basal forebrain, locomotion, feeding, bicuculline

Introduction

Dopamine signaling and the ventral striatopallidal circuitry modulate ingestive behaviors (Kelley et al., 1996; 2005). Systemic administration of L-DOPA and amphetamine, both of which increase extracellular levels of dopamine, decrease feeding in food deprived rats (Sangvi et al., 1975; Blundell and Latham, 1980; Winn et al., 1982). Infusions of GABAA and delta opioid receptor antagonists (Stratford et al., 1999; Smith and Berridge, 2005; Stratford and Wirtshafter, 2012; Inui and Shimura, 2014; Covelo, 2014) and mu opioid receptor agonists (Smith and Berridge, 2005) into the ventral pallidum (VP) produce vigorous ingestion in sated subjects. Interestingly, infusions of GABAA antagonists into the VP also produce abnormal postures and pivoting movements (Zahm et al., 2014; Subramanian et al., 2018; Reichard et al., 2019). The lateral preoptic area (LPO) lies adjacent to the VP and modulates locomotor activation (Zahm et al., 2014) as well as thirst and drinking (Coburn and Striker, 1978; Saad et al., 1996). While pivoting is not seen following infusion of GABAA antagonist into the LPO (Zahm et al., 2014; Subramanian et al., 2018), the extent to which the VP-provoked ingestion generalizes to the LPO is unknown. Nor is it known if VP-elicited ingestion requires dopamine receptor signaling. To address these concerns, groups of sated rats were given injections of the dopamine D2 antagonist, haloperidol (hal), the D1 antagonist, SCH-23390 (SCH), or vehicle (veh) followed by forebrain infusions of bicuculline (bic) or veh and immediately thereafter scored for open field movements and ingestion in a free feeding paradigm.

Methods and Materials

Subjects

Male Sprague Dawley rats (250–320 g), housed in groups of 3–4 before and singly after surgeries, were maintained on a 12 hour light-dark cycle in a temperature- and humidity-controlled vivarium with chow and water available ad libitum. All protocols were approved by the Saint Louis University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with guidelines provided in the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Drugs

All chemicals and drugs, except as noted, were acquired from the Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO, USA). The gamma-aminobutyric acid A (GABAA) receptor antagonist, 9(R)-(−)-bicuculline methbromide (bic) was dissolved in sterile 0.9% saline (veh, Hospira Inc., Lake Forest, IL). Haloperidol (hal) was prepared in a mixture of 20% ethanol, 50% propylene glycol and 30% distilled water as a stock solution, which was diluted with veh for intraperitoneal injections. Hal preferentially binds dopamine D2–D3 relative to D1 class dopamine receptors, whereas SCH preferentially binds D1 (Christensen et al., 1984; Hall et al., 1985; Leslie et al., 1987 a; b; Sokoloff et al., 1990; Bourne, 2001).

Guide cannula placement

Rats were deeply anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (72 mg/kg) and xylazine (11.2 mg/kg) injected intraperitoneally as a cocktail consisting of 45% ketamine (100 mg/ml), 35% xylazine (20 mg/ml) and 20% saline at a dose of 0.16 ml/100 g of body weight. Anesthetized rats were mounted in a Kopf stereotaxic instrument and incisions were made to expose the skulls, in which small burr holes were made over targeted sites. Stainless steel guide cannulae (22 gauge) 13 mm in length were inserted to a depth 2 mm above the centers of the targets and fixed with dental cement anchored to stainless steel screws set in the skull. Stainless steel wire obturators were inserted into the guide cannulae to maintain patency. The incisions were closed with wound clips and the rats were given i.p. injections of Buprenorphine SR (1 mg/kg) and kept warm until they awoke. Consistent with previous reports that unilateral and bilateral LPO infusions generate the same behavioral response, whereas bilateral VP infusions are required to generate a behavioral response (Zahm et al., 2014; Subramanian et al., 2018), cannulae were implanted unilaterally in the LPO (n=7) and bilaterally in the VP (n=10).

Apparatus

The tests were performed in activity monitoring chambers, each comprising a square, white, 43.2 × 43.2 cm floor and clear, 30.5 cm high plexiglass walls (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT). Fixtures containing horizontal rows of 16 point-source infrared illuminators equispaced at 2.54 cm were affixed to the wall on one side of the chambers at heights of 2.54 and 12.7 cm from the floor. Photodetectors were placed on the opposing walls. The lower bank comprised two sets of illuminators and detectors mounted on adjacent walls at a right angle to each other so as to form a grid of 16 × 16 intersecting light beams for measurement of horizontal (forward) locomotion, whereas the upper consisted of a single illuminator/detector pair to reveal rearing. Beam breaks were evaluated with the aid of Activity Monitor software (Med Associates). The monitoring chambers were housed inside dimly illuminated sound attenuating chambers with exhaust fans running (Med Associates).

Effects of dopamine antagonists on ingestion and movements following infusions of bic into the VP

Five days after cannulae were implanted, the rats were brought to the behavior testing room where they were habituated to the apparatus containing the sweet and chow pellets for twenty minutes on three successive days without receiving injections or infusions. On the fourth day, the rats received an i.p. injection of veh and thereafter either veh, 0.1 mg/kg hal or 0.01 mg/kg SCH, alternated on successive days for the duration of the experiments. Thirty minutes after each injection they received bilateral infusions of bic into the VP and were placed immediately in the activity monitors with ad lib access to the sweet and chow pellets

Intracranial infusions were carried out by removing the obturators from the guides and inserting stainless steel injector cannulae (28 gauge) 15 mm in length, connected by a short length of polyethylene tubing (PE 20 0.38/1.09, Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, cat. # 51155) to the Luer needle of a 1.0 μl Hamilton syringe, through and to a depth 2 mm past the tips of the guide cannulae. Infusate was propelled through the injectors at a rate of 0.25 μl/min by a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, model ‘11’ plus) for a duration of one minute, resulting in infusions of 0.25 μl. Bic was prepared at a dilution of 1 mg/3 ml, which resulted in delivery of 67 ng/0.25 μl. This concentration and rate of delivery produced robust locomotor activation in previous studies (Reynolds et al., 2006; Zahm et al., 2014; Subramanian et al., 2018). At completion of the infusions, the injectors were removed and the rats were placed in the activity monitor with two plastic petri dishes, one containing 45 mg chocolate flavored sucrose (sweet) pellets, and the other containing MLab rodent chow pellets (TestDiet, Richmond, IN).

Numbers of ingested pellets were calculated by dividing the difference between the total weight of the pellets provided before each experiment and the weight remaining, including crumbs, at the conclusion of the experiment by the average pellet weight, which was 49 mg. Experiments were begun during the second hour of the light period, after the rats had fed ad libitum during the preceding dark period. The number, duration and direction of pivots and pivoting episodes were monitored visually. A 360° revolution counted as one pivot. A pivoting episode was defined as at least three pivots in succession without interruption.

Localization of Injections

The rats were deeply anesthetized as described and perfused trans-aortically with 0.01 M Sorenson’s phosphate buffer (SPB; pH 7.4) containing 0.9% sodium chloride and 2.5% sucrose, followed by 0.1 M SPB (pH 7.4) containing 4% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% sucrose. The perfused brains were removed and placed in the same fixative for four hours and then in a 30% sucrose solution overnight. Parts of the brains containing infusion sites were sectioned with a cryostat into three adjacent series of 50 μm thick sections. The first series was thaw-mounted onto subbed glass slides and the rest were stored in glass vials containing 0.1 M SPB. The mounted sections were defatted overnight in a 1:1 solution of chloroform and methanol and, after rehydration in decreasing concentrations of methanol in water (100%, 95%, 90%, 80%, 70% and 50%), placed in a filtered solution of 0.1% cresyl violet acetate in 0.3% glacial acetic acid for 10 minutes. The stained sections were dehydrated in increasing concentrations of MeOH and then placed in xylene prior to coverslipping with Permount. Sections were viewed with brightfield optics with an Olympus BX51 microscope and the locations of the injector tips were mapped with the aid of the Neurolucida hardware/software platform (MBF Bioscience, version 4.70.3). The maps were exported to Adobe Illustrator CS2 for preparation of illustrations.

Statistics

The means of beam breaks and pellets ingested per session following veh vs bic infusions into the LPO or VP were statistically compared using paired t-tests with the critical limit set at p < 0.05. To determine the effects of dopamine antagonists, the means of pellets ingested, pivoting episodes and pivots per episode from each treatment group were statistically compared with a one-way ANOVA and a post hoc Holm-Sidak test with the critical limit set at p < 0.05.

Results

Bic infusions into the VP but not LPO elicit compulsive ingestion

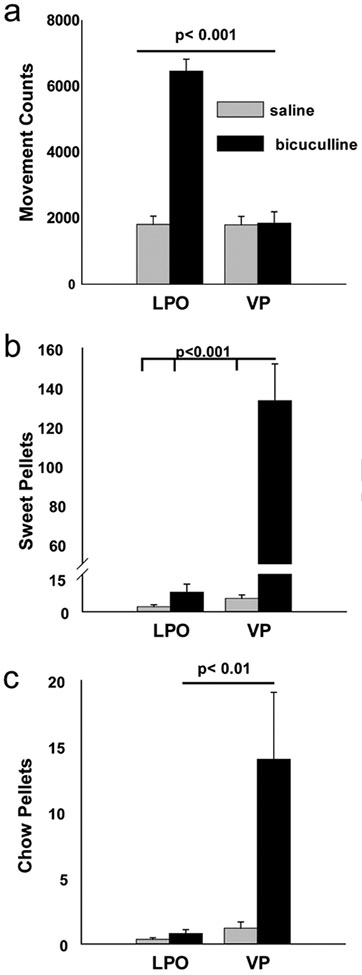

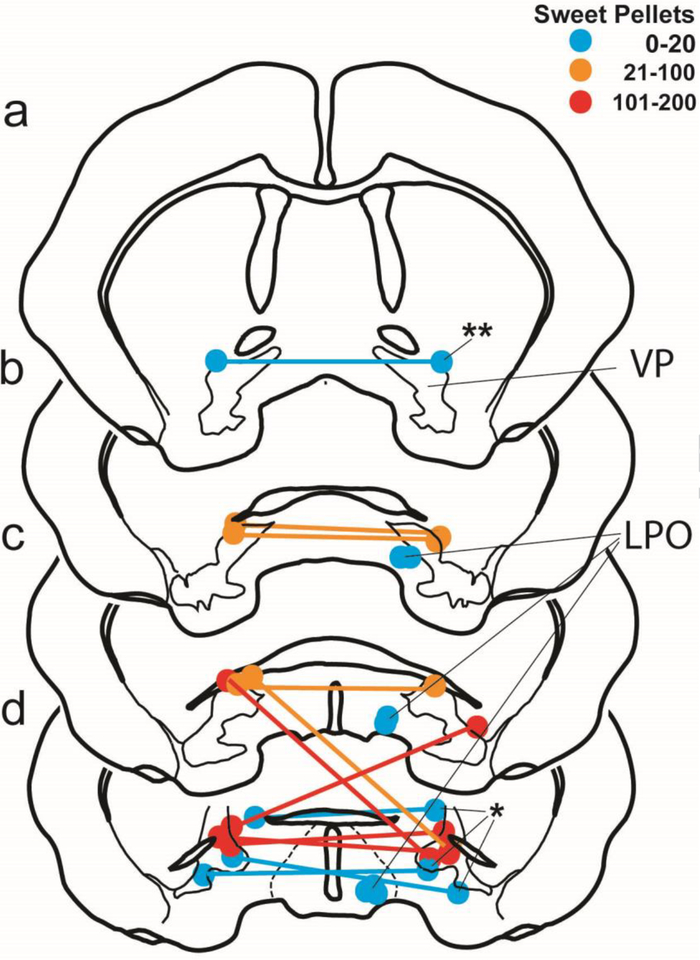

Locomotor counts were significantly more numerous after bic than veh infusions into the LPO [LPO bic: 6467 ± 361 vs LPO sal: 1815 ± 248; t(18)=10.612, p<0.000001] and bic infusions into the VP [VP bic: 1850 ± 345; t(17)=9.186, p<0.000001] (Fig. 1A). Alternatively, VP bic infusions produced locomotor counts not significantly different from veh infusions into the VP [VP sal: 1801 ± 255; t(14)=0.107, p=0.916] or LPO. In contrast, following VP bic infusions significantly more sweet pellets were ingested than after VP veh or LPO bic infusions (Fig. 1B) [VP bic: 133 ± 18.7 vs VP sal: 5.3 ± 1.4; t(7)=6.579, p =0.0003; LPO bic: 7.8 ± 3.3; t(16)=7.347, p<0.000001], whereas pellets ingested following LPO veh and bic infusions were not different [LPO sal: 2.0 ± 0.8; t(9)=1.935, p=0.08]. Likewise, VP bic, as compared to VP veh or LPO infusions, significantly increased the number of chow pellets (Fig. 1C) ingested [VP bic: 14.0 ± 5.0 vs VP sal: 1.2 ± 0.5; t(7)=2.6, p =0.03; LPO bic: 0.8 ± 0.3; t(16)=2.929, p=0.009; LPO sal: 0.4 ± 0.1; t(16)=3.035, p=0.008], whereas numbers of chow pellets ingested by the latter three groups did not differ. Caudal placements of VP infusion sites resulted in greater numbers of sweet pellets being ingested (Fig. 2). In cases in which the injection cannulae hit the VP on only one side of the midline, compulsive ingestion was not elicited (Fig. 2, asterisks). The groups displayed significant preference for sweet over chow pellets [t(7)=6.274, p=0.0004], although one subject (Fig. 2, double asterisks) preferentially ingested chow over sweet pellets (chow: 73.2 ± 18.0 vs sweet: 0.6 ± 0.6).

Figure 1:

Bic infusions into VP but not LPO elicit ingestion in sated rats. a. Total distance traveled, assessed by the number of horizontal beam breaks, was significantly greater following LPO bic infusions (black bar, left) compared to VP bic infusions (black bar, right) and vehicle infusions (gray bars). VP but not LPO bic infusions (black bars) elicited compulsive ingestion of chow (b) and sweet (c) pellets. Significant differences are indicated on the graph..

Figure 2:

Map depicting a series of sections (a-e) through forebrain in rostral to caudal sequence showing the locations of the injector cannula tips. The ventral pallidum (VP) is outlined in a-e and the lateral preoptic area (LPO) indicated in c-d. Colors depict the average number of sweet pellets ingested following bic infusions as indicated on the graph. Dots depict infusion sites and connected dots indicate bilateral infusions. Cases in which at least one infusion missed the VP and thus were not included in analysis are indicated with an asterisk. The single case in which chow pellets were preferred over sweet pellets is indicated by two asterisks.

VP bic-elicited ingestion requires D2 but not D1 receptor signaling

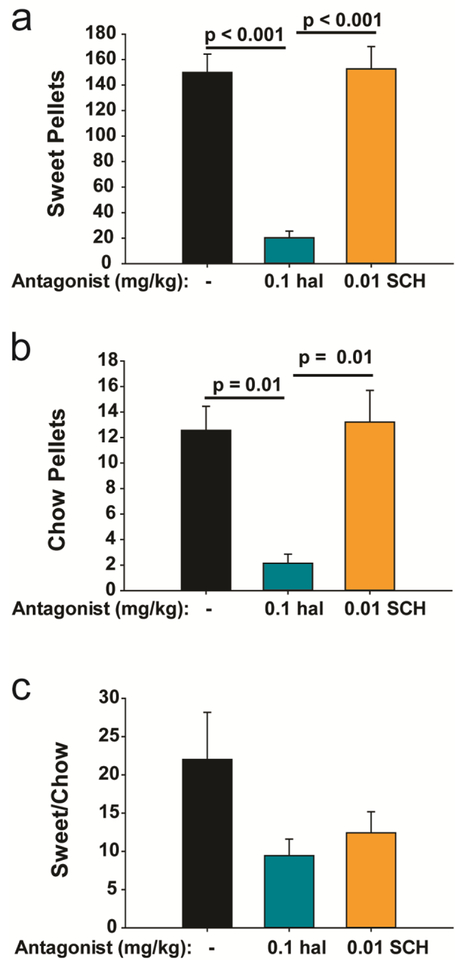

Pretreatment with 0.1 mg/kg hal, as compared to veh, significantly reduced the number of ingested sweet pellets (Fig. 3A) [hal: 19.2 ± 4.8 vs veh: 158 ± 15.7; t(18)=5.62, p< 0.001], whereas pretreatment with 0.01 mg/kg SCH did not [SCH: 183.0 ± 17.7; t(22)=1.10, p=0.3]. Pretreatment with hal also significantly reduced the numbers of chow pellets eaten (Fig. 3B) [hal: 2.1 ± 0.7 vs veh: 12.5 ± 1.9; t(18)=3.023, p=0.01], whereas pretreatment with 0.01 mg/kg SCH did not [SCH: 13.2 ± 2.5; t(22)=0.2310, p=0.8]. There were no significant differences in any parameter tested between the hal veh and SCH veh sessions thereby allowing data from those groups to be combined. Taken together, the results show that VP bic-elicited ingestion of sweet and chow pellets requires signaling through D2 but not D1 receptors. Preference for sweet over chow pellets was affected by neither antagonist, insofar as the ratio of ingested sweet to chow pellets did not differ significantly (Fig. 3C) between treatment groups [veh: 21.9± 6.2, hal: 9.4 ± 3.5, SCH 12.4 ± 2.7; F(2,25)=1.358, p=0.3]. The antagonist-associated reduction in ingestion also was not attributable to motor deficits, insofar as movement counts, but not ingestion, were significantly reduced by pretreatment with SCH (Fig. 4A) as compared to veh [SCH: 1498 ± 93 vs veh: 1998 ± 136; t(22)= 2.684, p= 0.04], whereas, hal reduced ingestion, but not movement [hal: 2078 ± 195; t(18)=0.351, p=0.8].

Figure 3:

VP bic-elicited ingestion requires D2 but not D1 receptor signaling. VP bic infusion elicited compulsive ingestion of sweet (a) and chow (b) pellets when animals received i.p. injections of haloperidol or SCH 23390 vehicle prior to VP bic infusions (black bars). Ingestion was attenuated by pretreatment with 0.1 mg/kg hal (blue bars) but not 0.01 mg/kg SCH (orange bars). Preference for sweet over chow pellets was not significantly altered by pretreatment with either antagonist (c).

Figure 4:

VP bic-elicited locomotion requires D1 but not D2 receptor signaling. a. VP elicited locomotion (black bar) was reduced by pretreatment with SCH (orange bar) but not hal (blue bar). Neither antagonist significantly altered the number (b) or duration (c) of the VP-bic elicited pivots. The data represent group averages (0.1 mg/kg hal n=6, 0.001 mg/kg SCH n=5). The depicted significance reflects Holm-Sidak post-hoc analysis after an ANOVA.

VP bic-elicited pivoting dyskinesias were not altered by dopamine receptor antagonists

Neither antagonist significantly altered the number of pivoting episodes (Fig. 4B) elicited by infusions into the VP of bic as compared to veh [hal: 10.8 ± 1.8, veh: 6.6 ± 1.2, SCH: 5.7 ± 1.1; F(2,25)=2.649, p=0.09]. Likewise, pretreatment with neither antagonist as compared to veh significantly affected the mean number of pivots per episode (Fig. 4C) [hal: 6.0 ± 1.9, veh: 4.4 ± 0.8, SCH: 3.3 ± 0.3; F(2,25)=1.469, p=0.25]. These results argue that the effects of hal and SCH on VP-elicited feeding and movement were not confounded by systematic differences in pivoting.

Discussion

Consistent with previous studies (Zahm et al., 2014; Subramanian et al., 2018; Reichard et al., 2019), the present experiments indicate that LPO and VP have different roles in the modulation of ingestion and movement. Here, the rats were regarded as sated insofar as they were tested immediately after the dark period, when they feed, and they did not eat following veh infusions into either the LPO or VP. Despite robustly increasing locomotion, disinhibiting the LPO provided no drive to consume in sated animals. The rats displayed fluid movements following LPO bic infusions and rarely stopped to investigate the dishes containing food pellets. Conversely, VP bic produced compulsive ingestion of sweet and chow pellets in the absence of increased locomotion. Between pivots and bouts of pivoting, VP bic-infused rats moved around the apparatus freely, displaying heightened interest in the food dishes and all the while sniffing the walls and floors, gaping, grasping and gnawing.

Dopamine antagonists revealed distinct roles for D1 and D2 receptor signaling in VP bic-elicited behaviors. Signaling through D2 receptors was required for VP bic-elicited ingestion, but not movements, whereas D1 receptor signaling was required for movements, but not ingestion. Interestingly, the preference for sweet over chow pellets was maintained in the presence of the D2 antagonist, suggesting that preference is independent of dopamine and may be mediated downstream (Norgren et al., 2006). SCH at 0.01 mg/kg significantly reduced locomotion, but not pellet ingestion, nor the preference for sweet pellets. We did not follow this up with a greater dose of SCH, reasoning that if an increased dose of SCH reduced pellet ingestion, the interpretation would be confounded by the greater motor deficit. Conversely, 0.1 mg/kg hal effectively suppressed ingestion in VP bic-infused rats in the absence of impaired locomotion. The preservation of locomotion is explicated by the observation that VP bic restores locomotion to baseline levels even in the presence of doses of hal up to 2 mg/kg (Subramanian et al., 2018), presumably by surmounting the potentiation, mediated by hal acting at D2 receptors in the Acb, of the strongly inhibitory action of the GABAergic ventral striatopallidal pathway (Heimer and Wilson, 1975; Mogenson et al., 1980; Mogenson and Nielsen, 1983; Zahm et al., 1985; Zahm and Heimer, 1990; Robertson and Jian, 1995; Shreve and Uretsky, 1988; (Austin and Kalivas, 1989; 1990; 1991; Lu et al., 1998; Kupchik et al., 2015; Root et al., 2015 Subramanian et al., 2018). To the contrary, insofar as the antagonists were given systemically in the present study, it cannot be presumed that the attenuation of VP bic-elicited ingestion by hal is due to an action in the striatopallidal pathway over numerous other potentially effective sites in the brain (Wise, 1974).

That compulsive ingestion requires signaling through dopamine D2 receptors whereas pivoting appears to be independent of D2 receptor signaling indicates that the VP can activate certain behavioral programs despite reduced, perhaps absent, dopamine signaling (but see Kitamura et al., 2001). Indeed, pivots persist following VP bic infusions even in the presence of 2 mg/kg hal, a very high dose (Subramanian et al., 2018). That hal blocks compulsive ingestion could be attributable to a hal-mediated silencing of a projection from the VP to lateral hypothalamus that is more D2 receptor dependent (Wise, 1974; Stratford and Wirtshafter, 2012). Another possibility is that VP bic-elicited ingestion, like pivoting, is a distinct, obligatory fixed action response, triggered by bic-mediated dysregulation of downstream projections from the VP to motor effectors (Zahm et al., 2014; Subramanian et al., 2018; Reichard et al., 2019). Different specific effects of dopamine D2 receptor blockade on different behaviors may owe to differences in the relative strengths with which various effector pathways from the VP are restrained by D2 receptor-gated striatopallidal inhibition (see above), but this requires additional study.

Pivoting also persisted in the presence of 0.01 mg/kg SCH, which is a dose that, despite significantly suppressing locomotion, may nevertheless suppress it insufficiently to quell VP bic-elicited pivoting. Given at 5 mg/kg, however, SCH suppressed VP bic-elicited pivoting and general locomotion to such a profound degree as to likely also preclude ingestion (Subramanian et al., 2018).

The observed (apparently) random cycling between pivoting, ingestion, gnawing, gaping and so on suggests that the disinhibited ventral pallidum activates behavior programs intrinsic to the spinal cord and brainstem. Sherrington (1910) and Brown (1911) independently demonstrated that neural circuitry sufficient for basic locomotion exists in the spinal cord. Complex behaviors such as eating, drinking, grooming and attack can be elicited by electrical stimulation of comparatively rostral structures in the midbrain of cats (Magoun et al., 1937; Wyrwicka and Doty, 1966; Sheard et al., 1967; Berntson et al., 1974) and rats (Chaurand et al., 1974; Micco, 1974; Waldbillig, 1975). Rats with transections at the rostral boundary of the superior colliculus display complex grooming, eating and defensive behaviors (Woods, 1964) and classical conditioning (Lovick and Zbrozyna, 1975). We like to speculate that activation of the VP engages these behavior programs, but additional objective data to further substantiate this idea are needed. The circuitry and mechanisms underlying such behavioral activation continue to be of great interest (Subramanian et al., 2018; Reichard et al., 2019).

The present results further distinguish the VP and LPO as distinct output structures that cooperatively and competitively contribute to the physical synthesis of adaptive behaviors (Zahm et al., 2014; Subramanian et al., 2018). Here we show that activation of the VP, but not LPO elicits compulsive ingestion, which is attenuated by blockade of D2, but not D1, receptors. Further, this study together with an accompanying one showing that stimulation of the VP emboldens behavior (Reichard et al., 2019) make evolutionary sense in that organisms often must discount threat in order to eat.

1). Funding:

The work was supported by USPHS NIH grant NS-23805 to DSZ. RAR received support from USPHS NIH grant T32 GM008306.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest

Research involving Human Participants and/or Animals: There were no human subjects. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) weighing 250–375 g were used in accordance with policy mandated in the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (http://grants.nih.gov/grants/olaw/references/phspol.htm) provided by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services with oversight by the Saint Louis University Animal Care Committee. Veterinary care was provided by the Saint Louis University Department of Comparative Medicine.

Ethical approval: All authors read and approved the final submitted manuscript.

Informed consent: There were no human subjects.

Literature Cited

- Austin MC, Kalivas PW. Blockade of enkephalinergic and GABAergic mediated locomotion in the nucleus accumbens by muscimol in the ventral pallidum. Jpn J Pharmacol 1989;50:487–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin MC, Kalivas PW. Enkephalinergic and GABAergic modulation of motor activity in the ventral pallidum. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1990;252:1370–1377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin MC, Kalivas PW. Dopaminergic involvement in locomotion elicited from the ventral pallidum/substantia innominata. Brain Res 1991;542:123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntson GG. Attack, grooming and threat elicited by stimulation of the pontine tegmentum in cats. Physiol Behav 1973;11:81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne JA. SCH 23390: the first selective dopamine D1-like receptor antagonist. CNS drug reviews 2001;7:399–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blundell JE, Latham CJ. Characterisation of adjustments to the structure of feeding behaviour following pharmacological treatment: effects of amphetamine and fenfluramine and the antagonism produced by pimozide and methergoline. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1980; 12:717–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TG. The intrinsic factors in the act of progression in the mammal. Proc R Soc Lond Ser B 1911;84:308–319. [Google Scholar]

- Chaurand JP, Vergnes M and Karli P (1974) [Elicitation of aggressive behavior by electrical stimulation of ventral mesencephalic tegmentum in the rat (author’s transl)]. Physiology & behavior 12:771–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen AV, Arnt J, Hyttel J, Larsen JJ, Svendsen O. Pharmacological effects of a specific dopamine D-1 antagonist SCH 23390 in comparison with neuroleptics. Life sciences 1984;34:1529–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn PC and Striker EM. Osmoregulatory thirst in rats after lateral preoptic lesions. J comp Physiol 1978;92:350–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covelo IR, Patel ZI, Luviano JA, Stratford TR and Wirtshafter D. Manipulation of GABA in the ventral pallidum, but not the nucleus accumbens, induces intense, preferential, fat consumption in rats. Behav Brain Res 2014;270:316–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall H, Kohler C, Gawell L. Some in vitro receptor binding properties of [3H]eticlopride, a novel substituted benzamide, selective for dopamine-D2 receptors in the rat brain. European journal of pharmacology 1985;111:191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimer L, Wilson RD. The subcortical projections of allocortex: Similarities in the neuronal associations of the hippocampus, the piriform cortex and the neocortex In: Santini M, editor. Golgi Centennial Symposium Proceedings. New York:Raven Press; 1975. p. 173–193. [Google Scholar]

- Inui T and Shimura T. Delta-opioid receptor blockade in the ventral pallidum increases perceived palatability and consumption of saccharin solution in rats. Behavior Brain Research 2014;269: 20–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley AE, Baldo BA, Pratt WE, Will MJ. 2005. Corticostriatal-hypothalamic circuitry and food motivation: integration of energy, action and reward. Physiol Behav 86:773–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley AE, Bless EP, Swanson CJ. 1996. Investigation of the effects of opiate antagonists infused into the nucleus accumbens on feeding and sucrose drinking in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 278:1499–1507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura M, Ikeda H, Koshikawa N and Cools AR. GABA A agents injected into the ventral pallidum differentially affect dopaminergic pivoting and cholinergic circling elicited from the shell of the nucleus accumbens. Neuroscience 2001;104:117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupchik YM, Brown RM, Heinsbroek JA, Lobo MK, Schwartz DJ, Kalivas PW. Coding the direct/indirect pathways by D1 and D2 receptors is not valid for accumbens projections. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:1230–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie CA, Bennett JP Jr. Striatal D1- and D2-dopamine receptor sites are separately detectable in vivo. Brain Res 1987a;415:90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie CA, Bennett JP Jr. [3H]spiperone binds selectively to rat striatal D2 dopamine receptors in vivo: a kinetic and pharmacological analysis. Brain Res 1987b;407:253–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovick TA and Zbrozyna AW. Classical conditioning of the corneal reflex in the chronic decerebrate rat. Brain Res 1975;89:337–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu XY, Ghasemzadeh MB, Kalivas PW. Expression of D1 receptor, D2 receptor, substance P and enkephalin messenger RNAs in the neurons projecting from the nucleus accumbens, Neuroscience 82;1998, 767–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magoun HW, Atlas D, Ingersoll EH and Ranson SW. Associated facial, vocal and respiratory components of emotional expression: An experimental study. J. Neurol. and Psychopathol 1937;17: 241–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micco DJ. Complex behaviors elicited by stimulation of the dorsal pontine tegmentum in rats. Brain Res. 1974;75:172–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogenson GJ, Nielsen MA. Evidence that an accumbens to subpallidal GABAergic projection contributes to locomotor activity. Brain Res Bull 1983;11:309–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogenson GJ, Wu M, Jones DL. Locomotor activity elicited by injections of picrotoxin into the ventral tegmental area is attenuated by injections of GABA into the globus pallidus. Brain Res 1980;191:569–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norgren R, Hajnal A, Mungarndee SS. Gustatory reward and the nucleus accumbens, Physiology & behavior. 2006,89:531–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichard RA, Parsley KP, Subramanian S, Stevenson HS, Schwartz ZM, SuraT Zahm DS. The lateral preoptic area and ventral pallidum embolden behavior. 2018;in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds SM, Geisler S, Berod A, Zahm DS. Neurotensin antagonist acutely and robustly attenuates locomotion that accompanies stimulation of a neurotensin-containing pathway from rostrobasal forebrain to the ventral tegmental area. Eur J Neurosci 2006;24:188–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson GS, Jian M. D1 and D2 dopamine receptors differentially increase Fos-like immunoreactivity in accumbal projections to the ventral pallidum and midbrain, Neuroscience. 1995;64:1019–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Root DH, Melendez RI, Zaborszky L and Napier TC. The ventral pallidum: Subregion-specific functional anatomy and roles in motivated behaviors. Prog in Neurobiol 2015;130:29–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad WA, Luiz AC, De Arruda Camargo LA, Renzi A and Manani JV. The lateral preoptic area plays a dual role in the regulation of thirst in the rat. Brain Research Bull 1996;39:171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanghvi IS, Singer G, Friedman E and Gershon S. Anorexigenic effects of d-amphetamine and l-DOPA in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1975;3:81–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheard MH and Flynn JP. Facilitation of attack behavior by stimulation of the midbrain of cats. Brain Research 1967;4:324–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrington CS. Flexion-reflex of the limb, crossed extension reflex and the stepping reflex and standing. J Physiol 1910;40:28–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shreve PE, Uretsky NJ. Effect of GABAergic transmission in the subpallidal region on the hypermotility response to the administration of excitatory amino acids and picrotoxin into the nucleus accumbens. Neuropharmacology 1988;27:1271–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KS and Berridge KC. The Ventral Pallidum and Hedonic Reward: Neurochemical Maps of Sucrose “Liking” and Food Intake. J Neurosci 2005;25:8637–8649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff P, Giros B, Martres MP, Bouthenet ML, Schwartz JC. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel dopamine receptor (D3) as a target for neuroleptics. Nature 1990;347:146–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratford TR, Kelley AE and Simansky KJ. Blockade of GABA(A) receptors in the medial ventral pallidum elicits feeding in satiated rats. Brain Research 1999;825:199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratford TR and Wirtshafter D. Lateral Hypothalamic involvement in feeding elicited from the ventral pallidum. European Journal of Neuroscience 2012;37:648–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian S, Reichard RA, Stevenson HS, Schwartz ZM, Parsley KP, Zahm DS. Lateral preoptic and ventral pallidal roles in locomotion and other movements, Brain structure & function 2018;223:2907–2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldbillig RJ. Attack, eating, drinking, and gnawing elicited by electrical stimulation of rat mesencephalon and pons. J Comp Physiol Psychol 1975;89:200–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn P, Williams SF and Herberg LJ. Feeding stimulated by very low doses of d-amphetamine administered systemically or by microinjection into the striatum. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1982;78:336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Lateral hypothalamic electrical stimulation: does it make animals ‘hungry’? Brain Research 1974;67:187–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods JW. Behavior of chronic decerebrate rats. J Neurophysiol 1964;27:635–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyrwicka W and Doty RW. Feeding induced in cats by electrical stimulation of the brain stem. Expl Brain Res 1966;1:152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahm DS, Heimer L. Two transpallidal pathways originating in the rat nucleus accumbens. J Comp Neurol 1990;302:437–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahm DS, Schwartz ZM, Lavezzi HN, Yetinkoff L and Parsley KP. Comparison of the locomotor-activating effects of bicuculline infusions into the preoptic area and ventral pallidum. Brain Struct Funct 2014;219:511–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahm DS, Zaborszky L, Alones VE, Heimer L. Evidence for the coexistence of glutamate decarboxylase and Met-enkephalin immunoreactivities in axon terminals of rat ventral pallidum. Brain Res 1985;325:317–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]