Abstract

The depth and complexity of data now available on chromosome 3D architecture, derived by new technologies such as Hi-C, has triggered the development of models based on polymer physics to explain the observed patterns and the underlying molecular folding mechanisms. Here, we give an overview of some of the ideas and models from physics introduced to date, along with their progresses and limitations in the description of experimental data. In particular, we focus on the Strings&Binders and the Loop Extrusion model of chromatin architecture.

Graphical/Visual Abstract and Caption

Different molecular mechanisms shape chromosome folding. In one classical scenario contacts between distal DNA sites are established by bridging transcription factors. In another one, DNA extruding molecules produce loops. We discuss polymer physics models developed to describe such scenarios.

Introduction

The investigation of the 3D structure of chromosomes in the nucleus of cells, and its functional implications, has been revolutionized by new technologies such as Hi-C (Lieberman-Aiden 2009), or the more recent GAM (Beagrie 2017) and SPRITE (Quinodoz 2018). Such technologies allow to measure the frequency of physical contacts between DNA sites genome-wide, returning for instance the network of interactions formed by regulatory regions and their target genes. In higher organisms chromatin contacts were discovered to have a complex, higher-order architecture (Bickmore 2013, Tanay 2013, Dekker 2016). While strong loops are identified between single pairs of distal DNA sites (Rao 2014), chromosomes are arranged into a sequence of Topological Associating Domains (TADs) (Nora 2012, Dixon 2012), megabase-sized regions marked by strong self-interactions. Structures exist at the sub-TAD level (Phillips-Cremins 2013) and at larger-scales, such as the ‘A/B compartments’ of open and closed chromatin (Lieberman-Aiden 2009). Additionally, TADs appear to form higher-order structures (meta-TADs) (Fraser 2015), arranged in a hierarchy of domains-within-domains, extending across chromosomal scales up to comprise entire chromosomes. Chromatin also forms hubs of inter-chromosomal interactions as those found around the nucleolus and nuclear speckles (Quinodoz 2018, and ref.s therein), along with hundreds of large, gene repressive domains associated with the nuclear lamina (LADs) that also contribute to the organization of the genome inside the nucleus (van Steensel 2017). Importantly, it has been shown that diseases, such as congenital disorders and cancer, can be linked to chromatin mis-folding (Lupiáñez 2015, Valton 2016, Weischenfeldt 2017).

To explain the complexity of the observed interaction patterns and the mode of action of their underlying molecular factors, different models from polymer physics have been introduced, focusing on different folding mechanisms. A class of models has considered the classical scenario of molecular biology where contacts between distal DNA sites and loops are established by diffusing molecules such as transcription factors (TFs) or some effective interaction potential, via mechanisms of equilibrium polymer thermodynamics (Kreth 2004, Nicodemi 2009, Bohn 2010, Barbieri 2012, Brackley 2013, Jost 2014, Brackley 2016, Chiariello 2016, Di Stefano 2016, Di Pierro 2016, Bianco 2018). A different class of polymer models have focused on off-equilibrium folding mechanisms (Lieberman-Aiden 2009, Sanborn 2015, Goloborodko 2016, Fudenberg 2016, Brackley 2017), in particular, on another classical scenario where loops are formed by molecules that bind to a site along DNA and extrude a loop. Those models are shedding light on the origin of contact patterns emerging from Hi-C data, as well as on the specific molecular mechanisms that fold different loci. Here, we briefly review the main features of such models, their comparison with experimental data and the current picture of the physical mechanisms underlying chromatin architecture.

Independent of the underlying physical processes, important computational approaches to reconstruct chromosome 3D conformations have been also developed by optimizing scoring functions of Hi-C data to extract a consensus structure (Duan 2010, Peng 2013, Zhang 2013, Hu 2013, Varoquaux 2014, Lesne 2014), its variability by resampling methods (Baù 2011, Rousseau 2011, Serra 2017), population of individual structures by likelihood maximization of contact data and other information (Kalhor 2012, Giorgietti 2014, Zhang 2015, Hua 2018). However, they are not discussed here.

Equilibrium polymer models of chromatin folding

A classical concept in molecular biology is that contacts between distal DNA sites, e.g., cis-regulatory elements and gene promoters, can be established by molecules such as transcription factors (TFs) that bridge them producing DNA loops. Indeed, a variety of molecular factors has been discovered to play a role in chromosome folding including a number of TFs and other molecules such as CTCF/Cohesin (Sanborn 2015), MLL3/4 (Yan 2017), polycomb repressive complex 1 (Kundu 2017), active and poised Pol-II (Barbieri 2017).

The scenario where DNA folding is mediated by bridging molecules or some effective interaction potential between distal sites has been considered by a class of physics models that investigated self-interacting polymer chains and their equilibrium properties (see, e.g., Kreth 2004, Nicodemi 2009, Bohn 2010, Barbieri 2012, Brackley 2013, Jost 2014, Di Pierro 2016 and ref.s therein). To summarize the main features of that class, here we focus on the Strings&Binders model (SBS), one of the first introduced (Nicodemi 2009).

THE STRINGS & BINDERS MODEL

In the SBS model a chromatin filament is represented by a standard model of polymer physics (de Gennes 1979), i.e. a self-avoiding chain of beads (a ‘string’, Figure 1a). Additionally, along the chain there are specific beads that can be bound and bridged by diffusing molecules (the ‘binders’). Polymer physics is then used to predict the 3D conformations of the system as they spontaneously emerge from the interaction between the binders and the polymer chain. The folding dynamics of the system can be investigated for instance by Monte Carlo or by full Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. In the latter case, beads and binders of the system, all subject to Brownian motion, obey Langevin equations, with particle interaction potentials derived from classical studies of polymer physics (Kremer&Grest 1990). In particular, a Lennard-Jones attractive potential, with an energy scale Eint, models the interactions between binders and their target beads (binding sites) along the polymer chain. The interaction energy Eint, and the concentration of diffusing binders, here denoted by c, are key parameters of the model (see below).

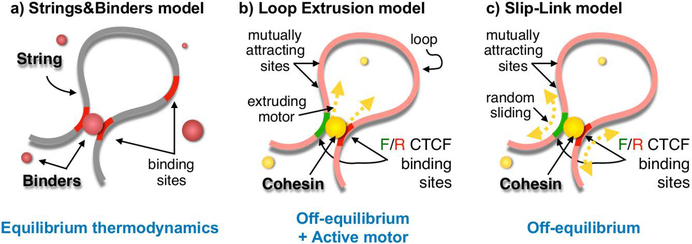

Figure 1. Schematic representation of polymer models describing chromatin folding.

a. The Strings&Binders Switch (SBS) model quantifies the biological scenario where diffusing transcription factors mediate DNA looping and folding. Its stable conformations can be derived by equilibrium thermodynamics.

b. The Loop Extrusion (LE) model quantifies the off-equilibrium folding scenario where an active motor binds to DNA and actively extrude a DNA loop.

c. The Slip-Link (SL) model is a variant without active, energy burning mechanisms, where DNA diffusively slips through a bridging factor.

Importantly, the SBS model has been shown to explain Hi-C, GAM and FISH data, and the 3D structure of genomic loci across chromosomal scales and cell types (Barbieri 2012, Fraser 2015, Brackley 2016, Chiariello 2016, Barbieri 2017, Bianco 2018).

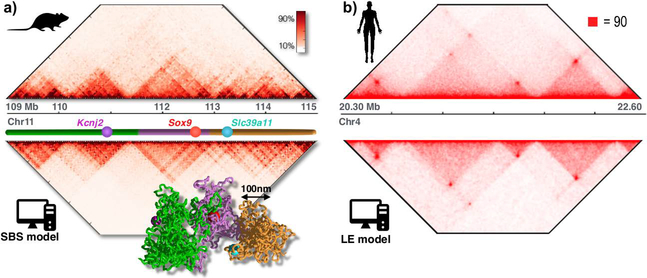

In particular, the SBS was used to describe the folding of loci such as the Sox9 locus in mouse embryonic stem cells (mESC) (Chiariello 2016) and the Epha4 locus in mouse and human cell types (Bianco 2018). Those genomic regions play a key role during cell differentiation and tissue development in mammals and structural variants in the loci are linked to human congenital diseases (Lupianez 2015, Franke 2017 and ref.s therein). The SBS model of the loci was shown to reproduce Hi-C data with good accuracy (Figure 2a, Chiariello 2016, Bianco 2018). In fact, the contact frequency matrices derived from the simulated ensembles of 3D conformations of the different loci have a comparatively high Pearson, r, and distance corrected Pearson correlation coefficient, r’ (r’ accounts for trivial genomic proximity effects, Bianco 2018) with corresponding experimental Hi-C matrices, ranging around r=0.95 and r’=0.60 respectively, below and above the scale of TADs. The model has been validated against independent capture Hi-C (cHi-C) data by its predictions on how chromatin refolds across mutants bearing structural variants, such as large deletions or duplications (Bianco 2018). The ensemble of thermodynamics conformations of the loci derived from the model helps visualizing in 3D the patterns seen in Hi-C data, such TADs and metaTADs (Figure 2a).

Figure 2. Polymer models can reproduce Hi-C data.

a. The folding of the Sox9 locus in mESC is described by the SBS model with good accuracy: Hi-C (Dixon 2012) and model derived contact data have a Pearson correlation r=0.95. A single-molecule 3D conformation of the locus derived from the SBS is also shown to visualize the 3D structure corresponding to Hi-C patterns. Adapted from (Chiariello 2016).

b. The LE model has been used to explain successfully the architecture of chromosomal loci where Cohesin/CTCF is the key driving force of folding, as the one in GM12878 cells shown in the example. Adapted from (Sanborn 2015).

THERMODYNAMIC PHASES AND CONFORMATIONAL CLASSES

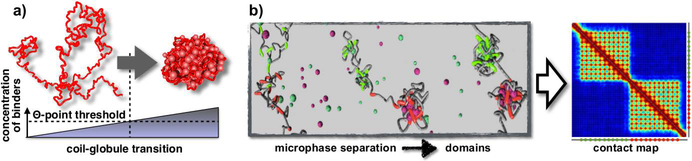

The idea behind the use of the equilibrium thermodynamics to describe chromosome folding is rooted in the scaling and universality concepts established in polymer physics (de Gennes 1979). They dictate that there is a one-to-one correspondence between the thermodynamics phases of the system and its conformational folding classes. Additionally, system details such as the specific shape of the interaction potentials do not affect the equilibrium phase diagram. Hence, by identifying the system thermodynamics states we can access the ensemble of its equilibrium 3D conformations. Consider, for example, the simple toy case of a SBS model with only one type of binders and binding sites (Figure 3a). In that case, as a function of the control parameters Eint and c, the system is subject to a coil-globule phase transition from a thermodynamic state corresponding to open conformations, equivalent to a randomly folded chain, to a collapsed state corresponding to compact globular conformations (Nicodemi 2009) (Figure 3a). The phase transition occurs switch-like by increasing, for example, the concentration c of the binders or their binding energy Eint above a threshold point. Notably, both energy and concentration of the system at the phase transition fall in the range expected from biological considerations (Barbieri 2012, Chiariello 2016). Importantly, the coil-globule transition is a feature universal across interacting polymers, mostly independent on their finer details (de Gennes 1979).

Figure 3. Microphase separation and domain formation.

a. In the SBS view, stable architectural classes of polymer physics correspond to different thermodynamics phases. The SBS toy model with only one type of binders and binding sites, exhibits a coil-globule phase transition, where its 3D conformation switches from being open to compact. Adapted from (Chiariello 2016).

b. In the SBS mixture model, the regions with red and green binding sites fold into distinct domains by microphase separation, as visible in the pairwise contact map. Adapted from (Barbieri 2012).

Microphase separation

The concept of microphase separation, in particular, has been proposed to explain the formation of patterns, such as TADs or metaTADs (Barbieri 2012, Chiariello 2016). It can be illustrated by the toy example of a block-copolymer, i.e., a SBS model with two types of binding sites (red/green) arranged in two blocks, each interacting with a specific type of binders (red/green, Figure 3b). In that model the two blocks can fold independently in either the coil or globule state, as described before. As they have no direct interactions, the system contact matrix exhibits two distinct domains, resembling TADs in Hi-C data (Figure 3b). In polymer physics, that concept is named microphase separation (Leibler 1980). Its implications to chromatin folding have been recently supported by novel exciting experimental results (Hnisz 2017, Larson 2017, Storm 2017). In a real locus, as the Sox9 above, different types of binding sites are required to explain Hi-C data (Chiariello 2016), not just two (red/green) as in the block-copolymer example. They have been shown to correlate each with a combination of different factors, rather than with a single molecule type, returning a picture where a combinatorial code of a few, key molecular factors is likely to regulate Hi-C patterns genome-wide.

Within the above framework, the different regions of a chromosome are expected to fold, at least asymptotically, into conformations belonging to such universality classes as envisaged by equilibrium polymer physics. This has been named the mixture model of chromatin organization (Barbieri 2012, Chiariello 2016), from which the results shown, e.g., for the Sox9 locus in Figure 2a have been derived. One of the limitations of equilibrium models, such as the SBS, is that they require additional hypotheses to explain the so-called CTCF convergence bias (Rao 2014), a specific, yet intriguing feature of loci whose folding is driven by CTCF sites, as described below. Yet, the mixture model also gives a straightforward explanation and a thermodynamic foundation, for instance, to microscopy observations where DNA is typically found organized in distinct open and closed regions, associated respectively to eu- and hetero-chromatin domains.

Off-equilibrium polymer models of chromatin folding

Another appealing scenario whereby distal DNA elements can recognize and meet each other envisages a DNA-sequence tracking mechanism: a molecular factor binds a pair of sites along a chromosome and extrudes a loop bridged by its binding points, scanning the sequence up to reach its anchoring targets (Figure 1b,c). That’s the core idea behind the Loop Extrusion (LE) Model (Sanborn 2015, Goloborodko 2016, Fudenberg 2016) and the Slip-Link (SL) Model (Brackley 2017) that we discuss below.

THE LOOP EXTRUSION MODEL

The LE model (Figure 1b) poses that a Cohesin complex acts as the extruding factor, whose anchor points along the DNA sequence are pairs of CTCF binding sites of opposite orientation. The motivation behind the latter hypothesis is to explain the observation that CTCF motifs positioned at the anchor points of Hi-C loops tend to be convergent (CTCF convergence bias) (Rao 2014). The LE model has been explored by coarse-grained MD simulations of polymers subject to Langevin dynamics (Sanborn 2015, Fudenberg 2016). In simulations, extrusion complexes are represented by harmonic bonds and forward/reverse oriented CTCF sites are represented by two types of specific polymer beads that can halt respectively forward and reverse subunits of the extrusion complex. Initially, each extrusion complex is bound to two adjacent monomers and next by sliding along the chain it can extrude a loop. Extrusion complexes can also stochastically dissociate and consequently release loops. Important parameters of the model are the density of extrusion complexes bound to the polymer chain, and their processivity, which is linked to the rate of dissociation of the complexes. Different choices of the parameters lead to the formation of various patterns in the simulated contact maps (Fudenberg 2016), such as TADs, loops at TAD corners and lines of enriched contacts along the TAD edges, all features clearly visible in Hi-C data.

The LE model is supported by a number of important observations: disruption of CTCF binding sites at specific loci has indeed shown that chromatin organization can be affected (Sanborn 2015, de Wit 2015, Guo 2015, Nora 2017) and, importantly, many of such experimental results can be successfully explained within the LE model scenario (Figure 2b). To better match Hi-C data, a formulation of the LE model also poses that a generic pair-wise attraction force, modeled by a Lennard-Jones attractive potential, must act between all DNA site pairs along the considered sequence (Sanborn 2015). In addition to reproducing Hi-C features and giving a natural interpretation to the CTCT convergence bias, the LE model has also been shown in agreement with FISH measurements of the distance distribution between some selected loci pairs (Sanborn 2015). However, the LE model cannot explain the experimental observation that chromatin compartments are maintained intact even upon severe depletion of chromosome-bound Cohesin (Nora 2017, Schwarzer 2017, Rao 2017). Such observations have raised the view that chromatin organization is only partially dependent on CTCF/Cohesin and maintained by other CTCF/Cohesin-independent mechanisms.

The other key hypothesis of the LE model is that the extruding factor producing the loops is an active motor, hence burning energy at each single step along the DNA sequence. The idea has been controversial because of the large amount of energy (and very high progression speed) required to organize chromatin at a genomic-scale (Brackley 2017). Additionally, while it has been recently shown that the Condensin complex can undergo an ATP based unidirectional active motion along a DNA template (Terakawa 2017), no similar evidences exist to date about Cohesin. That may point out that a CTCF/Cohesin based active loop extrusion motor may play an especially important role, in particular, in contexts where condensing is a main actor, such as at mitosis.

THE SLIP-LINK MODEL

To try to overcome some of the problems inherent to the LE model, an interesting variant, the Slip-Link model (SL, Figure 1c), considers a scenario without active motors (Brackley 2017). As in the LE, the SL model poses that the Cohesin complex becomes loaded at adjacent pairs of sites on the DNA chain and hand-cuffs the two together. However, differently than in the LE, each DNA site bridged by Cohesin can independently slide by thermal diffusion, hence, growing or shrinking a loop, up to when anchoring CTCF convergent sites are reached and the loop halted.

In the view proposed by the SL model, no ATP is needed to extrude loops: the required energy is all provided, at no cost, by the external thermal bath, as much as in the equilibrium models discussed above. Albeit diffusion is the origin of loop formation within the SL, technically the model describes an off-equilibrium system, because of the envisaged adsorbing boundary anchors. Computer simulations have shown that the SL model not only explains the CTCF convergence bias, but also well accounts for the size distribution of CTCF based loops, as derived by ChIA-PET data (Brackley 2017).

THE FRACTAL GLOBULE MODEL

Finally, we mention another off-equilibrium model, the Fractal Globule (FG) model of chromosome folding that was proposed with the first release of Hi-C data (Lieberman-Aiden 2009). It makes the a-priori hypothesis that chromatin is folded in a specific off-equilibrium polymer state, the ‘crumpled globule’, i.e., a transient, highly unstable (Schram 2013) conformation of a free polymer. The FG model predicts that the system contact matrix has a genomic distance related decay, however, it is uniform with no patterns whatsoever, hence the FG cannot explain the formation of specific DNA loops, as well as TADs and the other mentioned patterns observed in more recent experimental data (Dixon 2012, Nora 2012, Rao 2014). However, it is one of the first descriptions of folded chromosomes.

Conclusions

Summarizing, the SBS model quantifies the biological scenario where transcription factors mediate DNA looping and folding, based on basic concepts of polymer equilibrium thermodynamics where 3D structures spontaneously emerge from microphase separation of cognate binding sites along a chromosomal region (Nicodemi 2009, Barbieri 2012, Jost 2014). Interestingly, recent experimental results have shown that concepts such as microphase separation do occur in the nucleus (Hnisz 2017, Larson 2017, Storm 2017). The SBS envisages that the orchestrated action of combinations of a comparatively small number of TFs can produce the variety of patterns observed in HiC or GAM data (Chiariello 2016). The removal of one of such factors is expected to impact the corresponding level of chromosome organization. That could be consistent with the observation that the acute depletion of, say, Cohesin does lead to loss of chromosome structure at the scale of TADs (Rao 2017, Schwarzer 2017). On the other hand, as different factors contribute to the architecture, the model predicts the robustness (Bianco 2018) of the global structure to the removal of one single type of binder (which, as stated, is in general a combination of molecules, rather than a single molecule), hence, the removal of single factors should not erase all Hi-C patterns, as experimentally found (Nora 2017, Kubo 2017, Schwarzer 2017, Rao 2017). However, the depletion of a molecule that is a key component of different types of binders can induce an architectural collapse because multiple binding factors are simultaneously affected.

A limitation of the SBS is that it needs additional ingredients to account for the convergence bias observed at CTCF based loops. Nevertheless, the SBS model has been shown to describe with high accuracy the architecture of a variety of loci, ranging from Xist or Bmp7, to the 7q11.23 and the HoxB regions in mammalian genomes (Chiariello 2016, Annunziatella 2016, Barbieri 2017, Chiariello 2017). Similarly, models of interacting polymers, in the same class of the SBS, informed with data on specific TF binding sites, have been successfully employed to explain pairwise Hi-C contacts across genomic regions and organisms, such as murine erythroblasts (Brackley 2016), Drosophila (Jost 2014) and budding yeast (Cheng 2015). Additionally, machine-learning approaches have been developed to identify the genomic location of the minimal set of molecular factors required to explain folding, based only on architectural data with no a-priori assumptions beyond that chromosome conformations reflects polymer physics (Chiariello 2016, Bianco 2018).

The Loop Extrusion model (Sanborn 2015, Goloborodko 2016, Fudenberg 2016) quantifies another interesting scenario of chromatin folding, where an active motor (e.g., Cohesin) binds to DNA and actively extrude a DNA loop up to encountering oppositely oriented CTCF anchoring sites. A variant of the LE, the Slip-Link model proposes a similar scenario based on random sliding of the loop bridging sites, without requiring an active, energy burning mechanism (Brackley 2017). Importantly, both the LE and the SL models describe well folding at loci where CTCF is the main driving force and are consistent with the CTCF convergence bias (Sanborn 2015, Brackley 2017). In other cases, however, they have been shown to be unable to fit Hi-C contact data. For instance, knockout experiments of CTCF in the globin loci have shown that the 3D structure is preserved (Brackley 2016), highlighting that the LE/SL models cannot explain the architecture; conversely, the folding of those loci was described with good accuracy by thermodynamics mechanisms as those envisaged by the SBS model (Brackley 2016). Similarly, a study of the murine HoxB region in mouse embryonic stem cells showed that homotypic interactions occur between active and poised promoters well described by the SBS model, but inconsistent with CTCF based loops (Barbieri 2017). Additionally, there are examples of loci where the 3D architecture is different in different tissues, but the CTCF profile stays the same (Kragesteen 2018).

A criticism about models based on thermodynamic equilibrium is that there are no special reasons for chromosomes to be at equilibrium in the cell nucleus. Similarly, as huge variety of off-equilibrium states can exist, it may be a-priori difficult to choose the one which applies to describe chromatin. The successes of such models in explaining experimental data may give support to their microscopic assumptions, which remain to be fully investigated.

The emerging scenario is that different mechanisms contribute to shape the complex architecture of the genome of higher-organisms (Figure 1). They include, but are not limited to, both equilibrium processes, as those envisaged for instance in the SBS model, and off-equilibrium processes, such as those considered in the Loop Extrusion model. Indeed, polymer models that take account of both these mechanisms are recently being developed (Nuebler 2018, Pereira 2018) Further progresses from polymer physics can shed light on such molecular mechanisms and their implications in gene regulation. By those advancements, polymer models have been used to predict the effects of structural variants on the 3D organization of chromatin loci and the link with their associated phenotype (Bianco 2018). Hopefully, the progress in our understanding of chromosome architecture can help developing novel approaches to tackle diseases linked to chromatin mis-folding, such as congenital disorders and cancer (Lupiáñez 2015, Valton 2016, Weischenfeldt 2017).

Acknowledgments

MN acknowledges support from the EU ITN n. 813282 PEP-NET, NIH ID 1U54DK107977-01, CINECA ISCRA ID HP10CYFPS5 and HP10CRTY8P, the Einstein BIH Fellowship, and from computing facilities at the INFN, CINECA, and Scope/ReCAS at the University of Naples.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Andrea Esposito, Dipartimento di Fisica, Università di Napoli Federico II, and INFN Napoli, Complesso Universitario di Monte Sant’Angelo, 80126 Naples, Italy.; Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology, Max-Delbrück Centre (MDC) for Molecular Medicine, Robert-Rössle Straße, Berlin-Buch 13125, Germany.

Carlo Annunziatella, Dipartimento di Fisica, Università di Napoli Federico II, and INFN Napoli, Complesso Universitario di Monte Sant’Angelo, 80126 Naples, Italy..

Simona Bianco, Dipartimento di Fisica, Università di Napoli Federico II, and INFN Napoli, Complesso Universitario di Monte Sant’Angelo, 80126 Naples, Italy..

Andrea M. Chiariello, Dipartimento di Fisica, Università di Napoli Federico II, and INFN Napoli, Complesso Universitario di Monte Sant’Angelo, 80126 Naples, Italy..

Luca Fiorillo, Dipartimento di Fisica, Università di Napoli Federico II, and INFN Napoli, Complesso Universitario di Monte Sant’Angelo, 80126 Naples, Italy..

Mario Nicodemi, Dipartimento di Fisica, Università di Napoli Federico II, and INFN Napoli, Complesso Universitario di Monte Sant’Angelo, 80126 Naples, Italy.; Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology, Max-Delbrück Centre (MDC) for Molecular Medicine, Robert-Rössle Straße, Berlin-Buch 13125, Germany. Berlin Institute of Health (BIH), MDC-Berlin, Germany

References

- Annunziatella C, Chiariello AM, Bianco S, Nicodemi M (2016). Polymer models of the hierarchical folding of the Hox-B chromosomal locus. Phys Rev E 94, 042402. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.94.042402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri M, Chotalia M, Fraser J et al. (2012). Complexity of chromatin folding is captured by the strings and binders switch model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 16173–16178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204799109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri M, Xie SQ, Torlai Triglia E et al. (2017). Active and poised promoter states drive folding of the extended HoxB locus in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature Struct. Mol. Bio 24, 515. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baù D et al. (2011) The three-dimensional folding of the α-globin gene domain reveals formation of chromatin globules. Nature Str. Mol. Bio 18 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beagrie RA, Scialdone A, Schueler M et al. (2017). Complex multi-enhancer contacts captured by Genome Architecture Mapping (GAM), a novel ligation-free approach. Nature 543, 519. doi: 10.1038/nature21411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco S, Lupiáñez DG, Chiariello AM et al. (2018). Polymer Physics Predicts the Effects of Structural Variants on Chromatin Architecture. Nature Gen. 50, 662. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickmore WA, van Steensel B (2013). Genome architecture: domain organization of interphase chromosomes. Cell 152: 1270–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn M, Heermann DW (2010). Diffusion-driven looping provides a consistent framework for chromatin organisation. PLoS ONE 5:e12218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackley CA, Taylor S, Papantonis A, Cook PR, Marenduzzo D (2013). Nonspecific bridging-induced attraction drives clustering of DNA-binding proteins and genome organisation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110, E3605–11. doi:0.1073/pnas.1302950110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackley CA, Johnson J, Kelly S, Cook PR, Marenduzzo D (2016). Simulated binding of transcription factors to active and inactive regions folds human chromosomes into loops, rosettes and topological domains. Nucl. Acids Res 44, 3503–3512. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackley CA, Johnson J, Michieletto D et al. (2017). Non-equilibrium chromosome looping via molecular slip-links. Phys. Rev. Lett 119, 138101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.138101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng TMK, Heeger S, Chaleil RAG et al. (2015). A simple biophysical model emulates budding yeast chromosome condensation. eLife 4, e05565. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiariello AM, Annunziatella C, Bianco S, Esposito A, Nicodemi M (2016). Polymer physics of chromosome large-scale 3d organisation. Scientific Reports 6: 29775. doi: 10.1038/srep29775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiariello AM, Esposito A, Annunziatella C et al. (2017). A Polymer Physics Investigation of the Architecture of the Murine Orthologue of the 7q11.23 Human Locus. Front. Neurosci 11, 559. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Gennes PG (1979). Scaling Concepts in Polymer Physics. Cornell Univ. Press, Ithaca, NY. [Google Scholar]

- de Wit E, et al. (2015). CTCF Binding Polarity Determines Chromatin Looping. Molecular Cell 60, 676. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pierro M, et al. (2016). Transferable model for chromosome architecture. PNAS 113, 12168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613607113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke M, et al. (2016). Formation of new chromatin domains determines pathogenicity of genomic duplications. Nature 538, 265. doi: 10.1038/nature19800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, et al. (2015). CRISPR Inversion of CTCF Sites Alters Genome Topology and Enhancer/Promoter Function. Cell 162, 900. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker J, Mirny L (2016). 3D Genome as Moderator of Chromosomal Communication. Cell 164: 1110–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon JR, Selvaraj S, Yue F et al. (2012). Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature 485: 376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature11082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano M, Paulsen J, Lien TG, Hovig E, Micheletti C (2016) Hi-C-constrained physical models of human chromosomes recover functionally-related properties of genome organization. Scientific Reports 6: 35985. doi: 10.1038/srep35985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Z et al. (2010) A three-dimensional model of the yeast genome. Nature 465, 363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser J, Ferrai C, Chiariello AM et al. (2015). Hierarchical folding and reorganisation of chromosomes are linked to transcriptional changes during cellular differentiation. Mol Syst Biol 11, 852. doi: 10.15252/msb.20156492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fudenberg G, Imakaev M, Lu C et al. (2016). Formation of Chromosomal Domains by Loop Extrusion. Cell Reports 15, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgietti L, Galupa R, Nora EP et al. (2014). Predictive Polymer Modeling Reveals Coupled Fluctuations in Chromosome Conformation and Transcription. Cell 157, 950–963. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goloborodko A, Marko JF, Mirny LA (2016). Chromosome Compaction by Active Loop Extrusion. Biophysical Journal 110, 2162. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hnisz D, Shrinivas K, Young RA, Chakraborty AK, and Sharp PA (2017). A Phase Separation Model for Transcriptional Control. Cell 169, 13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Deng K, Qin Z, Dixon J, Selvaraj S, et al. (2013) Bayesian Inference of Spatial Organizations of Chromosomes. PLoS Comput. Biol 9: e1002893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua N, Tjong H, Shin H, Gong K, Zhou XJ, Alber F (2018) Producing genome structure populations with the dynamic and automated PGS software. Nat. Protoc 13:915–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost D, Carrivain P, Cavalli G, Vaillant C (2014). Modeling epigenome folding: formation and dynamics of topologically associated chromatin domains. Nucleic Acids Res 42, 9553–61. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalhor R, Tjong H, Jayathilaka N, Alber F & Chen L (2012) Genome architectures revealed by tethered chromosome conformation capture and population-based modeling. Nat. Biotechnol 30, 90–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kragesteen BK et al. (2018) Dynamic 3D Chromatin Architecture Determines Enhancer Specificity and Morphogenetic Identity in Limb Development. Nature Gen in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer K & Grest GS, Dynamics of entangled linear polymer melts: A molecular‐ dynamics simulation. J. Chern. Phys 92, 5057 (1990) [Google Scholar]

- Kreth G, Finsterle J, von Hase J, Cremer M, Cremer C (2004). Radial arrangement of chromosome territories in human cell nuclei: a computer model approach based on gene density indicates a probabilistic global positioning code. Biophys J 86, 2803–2812. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74333-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo N, et al. (2017). Preservation of Chromatin Organization after Acute Loss of CTCF in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells. BioRxiv doi.org/ 10.1101/118737 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu S, Ji F, Sunwoo H et al. (2017). Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 Generates Discrete Compacted Domains that Change during Differentiation. Molecular Cell 65, 432. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson AG, et al. (2017). Liquid droplet formation by HP1α suggests a role for phase separation in heterochromatin. Nature 547, 236. doi: 10.1038/nature22822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibler L (1980) Theory of Microphase Separation in Block Copolymers. Macromolecules 13, 1602. [Google Scholar]

- Lesne A, Riposo J, Roger P, Cournac A & Mozziconacci J (2014). 3D genome reconstruction from chromosomal contacts. Nat. Methods 11, 1141–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman-Aiden E, van Berkum NL, Williams L et al. (2009). Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science 326: 289–293. doi: 10.1126/science.1181369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupiáñez DG, Kraft K, Heinrich V et al. (2015). Disruptions of topological chromatin domains cause pathogenic rewiring of gene-enhancer interactions. Cell 161, 1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicodemi M, Prisco A (2009) Thermodynamic pathways to genome spatial organization in the cell nucleus. Biophys J 96: 2168–2177. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nora EP, Lajoie BR, Schulz EG et al. (2012). Spatial partitioning of the regulatory landscape of the X-inactivation centre. Nature 485: 381–385. doi: 10.1038/nature11049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nora EP, et al. (2017). Targeted Degradation of CTCF Decouples Local Insulation of Chromosome Domains from Genomic Compartmentalization. Cell 169, 930. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuebler J, Fudenberg G, Imakaev M et al. (2018) Chromatin organization by an interplay of loopextrusion and compartmental segregation. PNAS 115 (29) E6697–E6706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng C et al. (2013) The sequencing bias relaxed characteristics of Hi-C derived data and implications for chromatin 3D modeling. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira MCF, Brackley CA, Michieletto D et al. (2018). Complementary chromosome folding by transcription factors and cohesin. BioRxiv doi.org/ 10.1101/305359 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips-Cremins JE, Sauria ME, Sanyal A et al. (2013). Architectural protein subclasses shape 3D organization of genomes during lineage commitment. Cell 153: 1281–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinodoz SA, et al. (2018). Higher-order inter-chromosomal hubs shape 3-dimensional genome organization in the nucleus. Cell 174, 1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SSP, et al. (2014). A 3D Map of the Human Genome at Kilobase Resolution Reveals Principles of Chromatin Looping. Cell 159, 1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SSP et al. (2017) Cohesin Loss Eliminates All Loop Domains. Cell 5, 171. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau M, Fraser J, Ferraiuolo MA, Dostie J & Blanchette M (2011) Three-dimensional modeling of chromatin structure from interaction frequency data using Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanborn AL, Rao SSP, Huang S-C et al. (2015). Chromatin extrusion explains key features of loop and domain formation in wild-type and engineered genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112, E6456–65. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518552112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schram RD, Barkema GT, Schiessel H (2013). On the stability of fractal globules. The Journal of Chemical Physics 138, 224901. doi: 10.1063/1.4807723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer W et al. (2017) Two independent modes of chromatin organization revealed by cohesin removal. Nature 551, 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra F, Baù D, Goodstadt M, Castillo D, Filion GJ, Marti-Renom MA. (2017) Automatic analysis and 3D-modelling of Hi-C data using TADbit reveals structural features of the fly chromatin colors. PLoS Comput Biol. 13:e1005665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storm AR, et al. (2017). Phase separation drives heterochromatin domain formation. Nature 547, 241. doi: 10.1038/nature22989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanay A, Cavalli G (2013). Chromosomal domains: epigenetic contexts and functional implications of genomic compartmentalization. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 23: 197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terakawa T, et al. (2017). The condensin complex is a mechanochemical motor that translocates along DNA. Science 358, 672. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valton AL, Dekker J (2016). TAD disruption as oncogenic driver. Curr Opin Genet Dev 36, 34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2016.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Steensel B, Belmon AS (2017). Lamina-Associated Domains: Links with Chromosome Architecture, Heterochromatin, and Gene Repression. Cell 169, 780. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varoquaux N, Ay F, Noble WS & Vert J-P (2014) A statistical approach for inferring the 3D structure of the genome. Bioinformatics 30, i26–i33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Chen S-AA, Local A. et al. (2017). Histone H3 Lysine 4 methyltransferases MLL3 and MLL4 Modulate Long-range Chromatin Interactions at Enhancers. Biorxiv dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/110239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weischenfeldt J, et al. (2017). Pan-cancer analysis of somatic copy-number alterations implicates IRS4 and IGF2 in enhancer hijacking. Nature Genetics 49, 65. doi: 10.1038/ng.3722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B & Wolynes PG (2015) Topology, structures, and energy landscapes of human chromosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 6062–6067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Li G, Toh K-C & Sung W-K (2013) 3D chromosome modeling with semi-definite programming and Hi-C data. J. Comput. Biol 20, 831–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]