Abstract

We report a 28-day repeat dose immunotoxicity evaluation of investigational drug MIDD0301, a novel oral asthma drug candidate that targets gamma amino butyric acid type A receptors (GABAAR) in the lung. The study design employed oral administration of mice twice daily throughout the study period with 100 mg/kg MIDD0301 mixed in peanut butter. Compound dosing did not reveal signs of general toxicity as determined by animal weight, organ weight, or hematology. Peanut butter plus test drug (in addition to ad libitum standard rodent chow) did not affect weight gain in the adult mice, in contrast to weight loss in 5 mg/kg prednisone-treated mice. Spleen and thymus weights were unchanged in MIDD0301-treated mice, but prednisone significantly reduced the weight of those organs over the 28-day dosing. Similarly, no differences in spleen or thymus histology were observed following MIDD0301 treatment, but prednisone treatment induced morphological changes in the spleen. The number of small intestine Peyer’s patches was not affected by MIDD0301 treatment, an important factor for orally administered drugs. Circulating lymphocyte, monocyte and granulocyte numbers were unchanged in the MIDD0301-treated animals, whereas differential lymphocyte numbers were reduced in prednisone-treated animals. MIDD0301 treatment did not alter IgG antibody responses to dinitrophenol following dinitrophenyl-keyhole limpet hemocyanin immunization, indicating that systemic humoral immune function was not affected. Taken together, these studies show that repeated daily administration of MIDD0301 is safe and not associated with adverse immunotoxicological effects in mice.

Keywords: GABAAR, Asthma, Immunotoxicity, peanut butter, MIDD0301

Introduction

Asthma is an increasing public health challenge with a patient population approaching 10% of the global population. Low-dose inhaled corticosteroid (with or without a long-acting β2-agonist) inhalers are the mainstays of asthma treatment [1]. Yet, in refractory asthma, disease responds poorly to corticosteroids, prompting increasing oral dosing that is linked to greater side effects and ineffective in steroid-tolerant disease [2]. Injectable biologics can effectively target inflammation in a subset of asthma patients, but high costs permit their use in only severe disease [3, 4]. In contrast to these therapies, MIDD0301 has been developed to target GABAAR on airway smooth muscle (ASM) and inflammatory cells, providing a novel asthma drug mechanism of action [5].

MIDD0301 is an allosteric GABAAR agonist that has been shown to alleviate multiple symptoms of asthma in animal models after oral dosing [5]. The GABAAR is a membrane chloride ion channel that opens in the response to GABA. The receptor is a heteropentamer (comprised of subunits: α1–6, β1–3, γ1–3, δ, ε, π, θ, ρ1–3), and most often takes the form of two alpha, two beta and one tertiary subunit [6]. During the last decades, the role of GABAARs in the brain has been studied extensively and several drugs targeting this receptor are currently available to treat a variety of CNS indications [7].

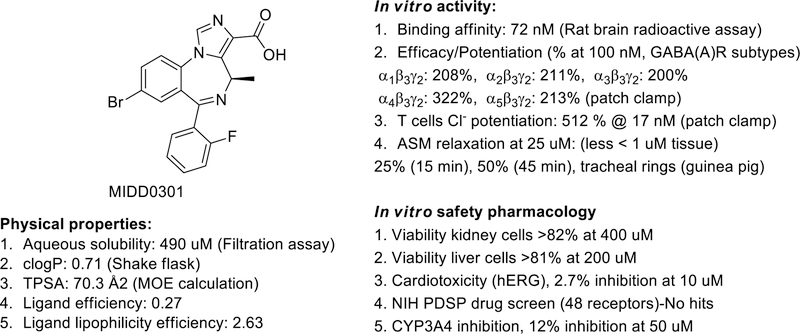

Recently, GABAAR subunits have been identified in many non-CNS cells (human protein atlas) [8]. Importantly, GABAAR alpha subunits have been identified in several cell types associated with asthma such as airway epithelia cells [9, 10], ASM [11], airway leukocytes (such as CD4+ T cells [12] and alveolar macrophages [13]). MIDD0301 relaxes constricted ASM and reduces airway hyperresponsiveness in an ovalbumin-induced murine model of asthma (MIDD0301 chemical structure and properties are summarized in Fig. 1) [5]. MIDD0301 has a half-life of almost 4 hr in the lung and only 5% of the circulating amount of MIDD0301 was found in the brain [14]. In sensorimotor studies, no CNS effects were observed at 1000 mg/kg. Importantly, MIDD0301 has excellent anti-inflammatory properties, reducing eosinophil and macrophage numbers in the lungs of asthmatic mice. A change of CD4+ T cell transmembrane current was observed in the presence of MIDD0301 (EC50 = 17 nM) and 20 mg/kg MIDD0301 p.o. was sufficient to reduce CD4+ T cell numbers in the asthmatic mouse lung. Furthermore, reduction of specific pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-17, IL-4 and TNFα, was observed in MIDD0301-treated asthmatic mice, confirming the immunoregulatory properties of MIDD0301. International regulatory bodies require that investigational new drugs be evaluated for the potential to produce immunosuppression (e.g., FDA Guidance, Oct. 2002 and ICH Expert Working Group advises to carry out immunotoxicity studies in agreement with the European Union, Japan and USA [15]). These studies are especially important for investigational drugs that are designed to reduce immune responsiveness or suspected to have immune suppression as a side effect. The importance of this study is the first systematic evaluation of a drug specifically targeting the GABAAR on immune cells, showing that therapeutically relevant anti-inflammatory activity can be achieved without off-target systemic immune suppression. Here, in addition to anatomical and histological measures, we adopted ICH S8 guidelines to investigate systemic immune suppressive effects of MIDD0301 by quantifying T cell dependent humoral immune responses to dinitrophenol (DNP) following immunization with dinitrophenyl-keyhole limpet hemocyanin (DNP-KLH) [16]. Safety of MIDD0301 was initially shown by administering twice daily doses of up to 100 mg/kg in mice. No adverse side effects were observed during five days of this treatment [5]. Herein, we expand upon these studies, and report the evaluation of the pharmacological effects of MIDD0301 in a 28-day repeat dose study with 100 mg/kg MIDD0301 twice a day. A battery of anatomic, hematologic and immunologic measures were evaluated in male and female mice to uncover any immune-related toxicities.

Figure 1.

Structure, physical properties, in vitro activity and safety pharmacology of MIDD0301.[34, 35]

Material and Methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology policy for experimental and clinical studies [17].

Chemicals.

MIDD0301 was synthesized using a published procedure [18]. A purity was of >98% was confirmed by HPLC. Identity was determined by 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR and high resolution mass spectrometry. Prednisone (>98% purity) was purchased from Sigma (P6254–1g). Skippy creamy peanut butter was used as vehicle.

Experimental animals.

Eight- and six-week-old Swiss Webster male and female mice (Charles River Laboratory) were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions, under standard conditions of humidity, temperature and a controlled 12-hr light and dark cycle and had free access to food and water. All animal experiments were in compliance with the University of Wisconsin−Milwaukee Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

MIDD0301 and prednisone formulation and administration.

Oral gavage: 0.2 ml of MIDD0301 in a 2% hydroxypropylmethylcellulose solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 2.5% polyethylene glycol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was administered by oral gavage with 20G gavage needles (Kent Scientific Corporation, Torrington CT, USA) to a group of mice twice a day for 7 days. Oral administration: MIDD0301 was formulated in 100 mg of peanut butter at a dose of 100 mg/kg. Twice a day, mice were taken from their cages and put in separate boxes that contained 100 mg of peanut butter or 100 mg of compound formulated peanut butter. The animals were left in the container during the feeding and returned 30 min. later to their group cage. During that time, all the peanut butter was consumed.

Immunogen preparation and administration:

A 1 mg/ml DNP-KLH aqueous solution was prepared from solid DNP-KLH (Sigma, 324121–100 mg) and 7.5 ml of that solution was added to 7.5 ml of a 40 mg/ml Al(OH)3 suspension (Thermo, Imject Alum 77161). 100 μl of this solution (50 μg DNP-KLH and 2 mg Al(OH)3) was injected i.p. on days 1 and 21 for immunization.

Necropsy.

Mice were euthanized by carbon dioxide asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation and blood withdrawn by cardiac puncture. Half of the blood was combined with EDTA for blood cell and platelet analysis. The other half was coagulated at room temperature and centrifuged for 10 min. at 2,000 rpm for DNP-specific IgG ELISA. After gross pathology, spleen and thymus were removed and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin overnight at 4°C, followed by three washes with water and storage in 70% ethanol before sectioning. The small intestine was excised and rinsed with water using a syringe with a blunt needle. The clean intestine was washed with 7% (vol/vol) acetic acid/PBS solution and lumen rinsed using a syringe with a blunt needle. After 5 min., the Peyer’s patches turned white and were readily counted by visual examination.

Hematology:

EDTA-treated blood samples were analysed with scil Vet ABC™ Hematology Analyzer providing 13 hematology parameters.

Histology:

General histology processing was performed by the Wisconsin Children’s Research Institute including drying, embedding, slicing and H&E staining. Representative sections were visualized by light microscopy at the indicated magnification.

Quantification of DNP IgG.

DNP IgG was quantified by ELISA using DNP coated wells (Kamiya Biomedical Company #KT-672). Serum from non-immunized mice was diluted 1:10,000 and DNP-KLH-immunized mouse blood was diluted 1:100,000. The assay was performed following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantification of MIDD0301 by LCMS/MS.

Collection for urine. Each MIDD0301-treated mouse was grasped gently by the back of the neck after feeding. With the mouse hanging vertically, a collection tube was placed beneath the penis or female urethral orifice to collect expressed urine without compulsion (50–100 μl). Urine was collected using this method during each day during the last week of compound dosing. For MIDD0301 quantification, 100 μl of urine was combined with 400 μl methanol containing compound 2 [19] as internal standard. The solution was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. and the supernatant evaporated to dryness (speedvac). The solid was reconstituted in 400 μl of methanol containing 4,5-diphenyl imidazole as second internal standard and filtered through a 0.22 μm nylon centrifugal filter unit (Costar). MIDD0301 was quantified using LCMS/MS, as recently reported.[5] Collection of faeces. Normally expressed faecal pellets were collected from the bedding on the last day of dosing and separated from any adherent wood bedding shavings. Faecal samples from each cage housing MIDD0301-treated animals were combined and dried overnight under vacuum (15 torr). The dried faeces was pulverized and 100 mg combined with 400 μl methanol containing compound 2 [19] as internal standard, and the protocol for urine samples was followed for MIDD0301 quantification.

Results

Previous oral dosing of MIDD0301 in mice for pharmacodynamic studies was carried out by oral gavage using 2% hydroxypropylmethylcellulose and 2.5 % polyethylene glycol [5]. During studies of five-day duration, no significant average animal weight changes were observed. Nevertheless, we then carried out a pilot study wherein a small group of mice were gavaged for seven days twice a day with vehicle alone to determine if this route would be suitable for longer-term studies. The study concluded that all mice receiving vehicle gavage twice a day lost weight (28.2 ± 2.3 g) during the seven-day trial in comparison to non-treated animals (29.1 ± 2.3 g). Oral gavage is a very accurate route of administration, however, it has been reported that even when carried out by very experienced personnel, respiratory complications, stomach distension and inflammation due to small lacerations of the esophagus can occur [20]. Furthermore, it has been shown that over time gavaged mice will show impaired weight gain due to reduced food intake [21]. Handling and restraining of animals during the feeding further induces stress, which has been associated with decreased food intake [22].

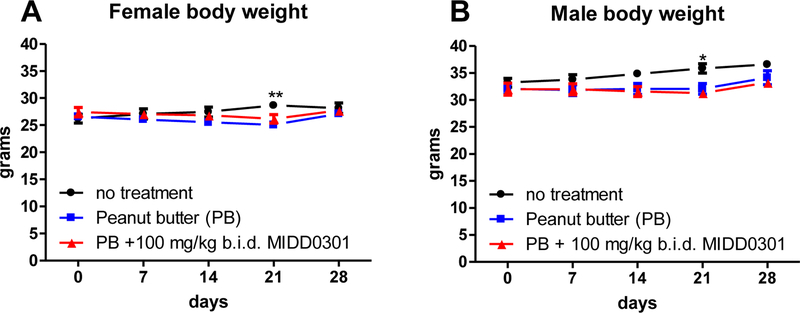

Based on these factors, we chose an oral administration regimen, which has been reported by others where glucose jelly was used to deliver the anti-obesity drug Rimonabant [23]. However, we decided to use peanut butter because of better uniformity for the formulation. To initiate the study, two groups of mice were trained to consume 100 mg of peanut butter twice a day for one week. To ensure precise administration of peanut butter or peanut butter with 100 mg/kg MIDD0301, each mouse was placed singly in a small feeding container with the measured amount of peanut butter and returned to the group housing cage after consumption. A third group of mice was not treated nor moved into feeding containers. The body weights of mice over the course of the study are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Average mouse body weights over the 28-day study. In separate feeding containers, Swiss Webster male and female mice (8 weeks of age) consumed peanut butter or peanut butter + 100 mg/kg MIDD0301 twice a day. Mice in the “no treatment” group were not moved into feeding containers. Animals were weighed every week (mean ± SEM, n = 5). 2-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis and indicated as * = p < 0.05 and ** = p < 0.01.

The average starting weight of the 8-week-old female Swiss Webster mice was lower than the corresponding males. During the course of the study, the average weights of MIDD0301-treated adult female and male mice were not significantly different from the peanut butter-only-treated group. Interestingly, at day 21 both male and female mice receiving peanut butter (with or without MIDD0301) had average weights less than untreated control mice. However, all groups exhibited similar weights at the end of the study (28 days). The average Swiss Webster female weight after 12 weeks was 26 ± 2 grams and 35 ± 2 grams for males, which is in agreement with the average, expected weight for this mouse strain [24]. In addition to weight measurements, gastrointestinal distress was assessed by any observation of unformed stool, diarrhoea or soiled anal region. Any change in grooming behaviour was determined by assessment of grooming activities and hair coat (piloerected or greasy). Behaviour abnormalities were determined by the lack of movement (including any abnormal eating or drinking activities and posture), abnormal respiration, lack of reflex towards touch, bite wounds among cage mates or overlay aggressive behaviour (biting) during handling. No such differences were observed in any group.

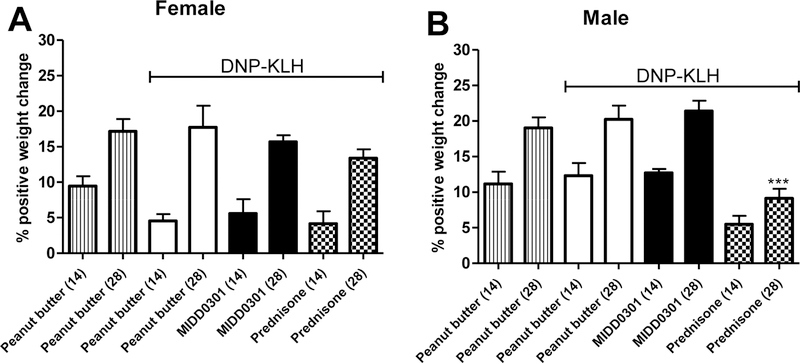

To determine the effect of MIDD0301 on systemic immune function, female and male 6-week-old Swiss Webster mice were immunized with 50 μg DNP-KLH in alum on days one and 21. Consumption of peanut butter formulated MIDD0301 (100 mg/kg, twice a day), peanut butter + prednisone (5 mg/kg/day) or peanut butter alone was carried out for 28 consecutive days. During that period, mice were weighted on days 14 and 28 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of DNP-KLH immunization on average body weight. In separate feeding containers, Swiss Webster female and male mice (6 weeks of age at the beginning of the study) consumed peanut butter, peanut butter + MIDD0301 (100 mg/kg, twice a day) or peanut butter + prednisone (5 mg/kg/day). Three groups were immunized with DNP-KLH on days 1 and 21. Animals were weighed on days (14) and (28). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 5. ANOVA was used for statistical analysis, *** = P < 0.001.

The average weight of female mice increased as expected for the non-immunized and DNP-KLH immunized control groups over the course of four weeks. No significant changes were observed between these two groups. Furthermore, no significant changes were observed for the MIDD0301 (100 mg/kg, twice a day) and prednisone (5 mg/day) treated female mice in comparison to their corresponding peanut butter only control group. Consistent with the results for female mice, DNP-KLH immunization did not cause significant weight changes in male mice over the study duration, in comparison to the non-immunized mice. The average weight of male mice administered MIDD0301 (100 mg/kg, twice a day) was similar to the peanut butter only control group. However, DNP-KLH immunized male mice treated with prednisone (5 mg/kg/day) had significantly reduced average weight at the 28-day time point, in comparison to peanut butter only treated DNP-KLH immunized male mice.

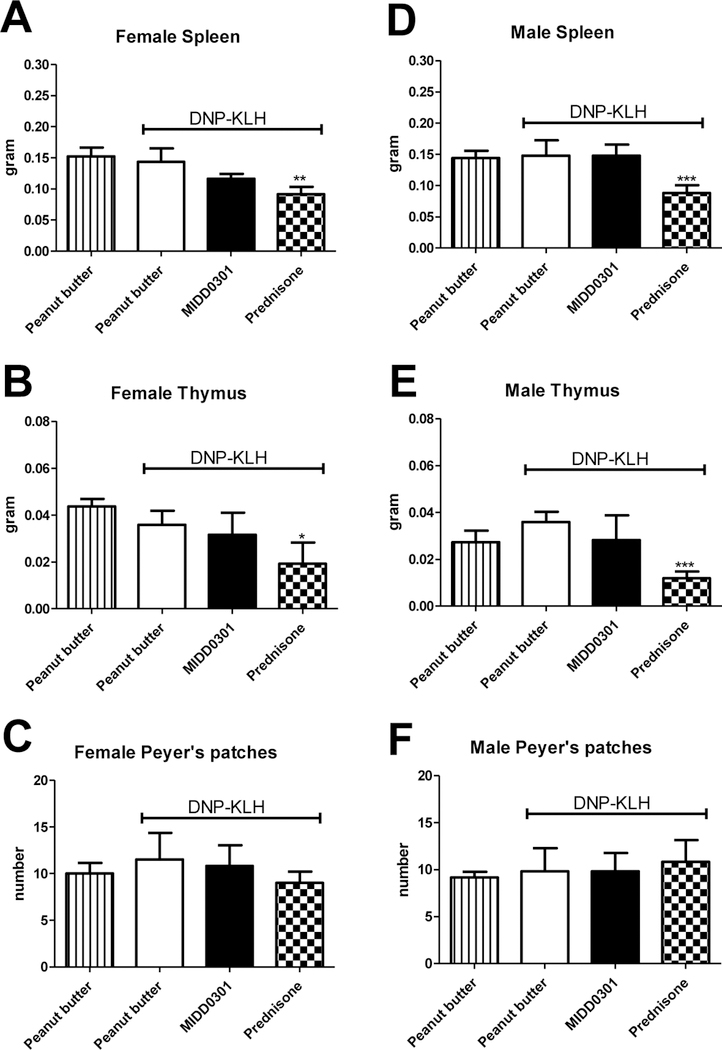

Lymphoid organs and tissues, including thymus, spleen and Peyer’s patches were evaluated in all mouse groups after the 28-day MIDD0301 or prednisone treatment regimens. The results are presented in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of lymphoid organs and Peyer’s patches in DNP-KLH immunized Swiss Webster mice after 28 days of treatment. Mice were 6 weeks old at the beginning of the study. A-C) Female Swiss Webster mice consumed peanut butter, peanut butter + MIDD0301 (100 mg/kg, twice a day) or peanut butter + prednisone (5 mg/kg/day). D-F) Corresponding groups of male Swiss Webster mice were treated in the same fashion. After 28 days, organs were harvested and weighted and intestines dissected for Peyer’s patch counting. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 5. ANOVA was used for statistical analysis: * = p < 0.05; ** = p < 0.01, and; *** = p < 0.001.

No significant differences were observed for spleen and thymus weights or Peyer’s patch numbers between peanut butter fed DNP-KLH immunized and non-immunized animals (Fig. 4, A-F). Spleen and thymus from DNP-KLH immunized MIDD0301 treated male and female mice had weights similar to corresponding DNP-KLH immunized mice given peanut butter alone. However, both male and female mice treated with 5 mg/kg/day prednisone had significantly smaller spleen and thymus weights in comparison to peanut butter only treated DNP-KLH immunized mice. The numbers of Peyer’s patches were unchanged in all groups. Lymphoid organs were further evaluated for gross histological alterations by H&E staining. The images are shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

H&E-stained sections of mouse spleens (A-H, 40x) and thymus (I-P, 100x). A&I) male mice, peanut butter, B&J) female mice, peanut butter, C&K) male DNP-KLH-immunized mice, peanut butter, D&L) female DNP-KLH-immunized mice, peanut butter, E&M) male DNP-KLH-immunized mice, peanut butter + MIDD0301 (100 mg/kg) twice a day for 28 days, F&N) female DNP-KLH-immunized mice, peanut butter + MIDD0301 (100 mg/kg) twice a day for 28 days. G&O) male DNP-KLH-immunized mice, peanut butter + prednisone 5 mg/kg/day for 28 days, H&P) female DNP-KLH-immunized mice, peanut butter + prednisone 5 mg/kg/day for 28 days.

H&E-stained spleen sections reveal typical histological presence of white (lymphoid follicles) and red pulp in all mouse groups. The cellular arrangements of follicles show no remarkable differences among the groups, except for the prednisone-treated animals (Fig. 5, G and H) that exhibited smaller and less uniform follicle size. Similar splenic changes have been reported in patients taking corticosteroids over a long period of time [25]. The H&E staining also highlighted the lymphocyte-rich white pulp, with well-defined features of centrally located germinal centers and the surrounding marginal zone for all spleen sections. The thymus histology of all groups appeared unchanged following treatment. The medulla and cortex regions were well defined in all groups and the thymus cell density appeared unchanged in all groups. Overall, no significant changes in the spleen and thymus histology were observed after repeated MIDD0301 treatment, however, prednisone-treated animals did exhibit some alteration in spleen histology. Blood was collected from mice after the 28-day treatment regimen for hematologic evaluation. The evaluation is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Hematology parameters for non-immunized and DNP-KLH-immunized Swiss Webster mice after indicated treatment for 28 days. The data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 5.

| Mouse (Male) | Peanut buttera | Peanut butterb | MIDD0301b | Prednisone b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNP-KLH-immunization | ||||

| cWBC ×103 (mm3) | 6.4 ± 0.7 | 6.2 ± 0.5 | 6.1 ± 0.7 | 5.8 ± 0.7 |

| dRBC ×106 (mm3) | 8.7 ± 0.2 | 8.1 ± 0.1 | 8.3 ± 0.2 | 8.0 ± 0.1 |

| eHGB (g/dl) | 14.9 ± 0.2 | 14.7 ± 0.2 | 15.1 ± 0.3 | 15.4 ± 0.2 |

| fHCT (%) | 45.1 ± 0.8 | 41.9 ± 0.3 | 43.3 ± 1.2 | 42.8 ± 0.3 |

| gMCV (μm3) | 52.0 ± 0.8 | 51.8 ± 0.8 | 51.8 ± 0.4 | 53.4 ± 0.9 |

| hMCH (pg) | 17.2 ± 0.3 | 18.2 ± 0.4 | 18.2 ± 0.2 | 19.3 ± 0.3 |

| iMCHC (g/dl) | 33.1 ± 0.2 | 35.1 ± 0.4 | 35.0 ± 0.3 | 36.1 ± 0.2 |

| kRDW (%) | 15.0 ± 0.3 | 15.0 ± 0.4 | 15.0 ± 0.2 | 15.7 ± 0.7 |

| lPLT x103 (mm3) | 986 ± 67 | 880 ± 40 | 903 ± 37 | 944 ± 27 |

| mMPV (μm3) | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.1 |

| nDIFF (%) | ||||

| oLYM | 55.0 ± 2.0 | 44.0 ± 2.9 | 50.0 ± 0.7 | 36.6 ± 2.4 |

| pMON | 10.5 ± 0.5 | 9.9 ± 0.3 | 9.4 ± 0.2 | 11.3 ± 0.3 |

| qGRA | 34.5 ± 2.1 | 46.1 ± 2.8 | 40.6 ± 0.7 | 52.1 ± 2.5 |

| Mouse (Female) | Peanut buttera | Peanut butterb | MIDD0301b | Prednisone b |

| DNP-KLH-immunization | ||||

| cWBC x103 (mm3) | 6.1 ± 0.2 | 6.5 ± 0.6 | 5.4 ± 0.7 | 7.4 ± 0.9 |

| dRBC x106 (mm3) | 8.4 ± 0.1 | 7.5 ± 0.2 | 8.0 ± 0.1 | 7.8 ± 0.1 |

| eHGB (g/dl) | 14.6 ± 0.3 | 14.4 ± 0.2 | 14.2 ± 0.1 | 15.0 ± 0.2 |

| fHCT (%) | 43.4 ± 0.9 | 39.7 ± 0.8 | 41.6 ± 0.3 | 41.1 ± 0.5 |

| gMCV (μm3) | 51.8 ± 0.6 | 53.4 ± 0.9 | 52.5 ± 0.9 | 52.6 ± 0.9 |

| hMCH (pg) | 17.3 ± 0.2 | 19.4 ± 0.6 | 18.3 ± 0.3 | 19.2 ± 0.4 |

| iMCHC (g/dl) | 33.6 ± 0.3 | 36.4 ± 0.6 | 35.0 ± 0.3 | 36.6 ± 0.4 |

| kRDW (%) | 14.5 ± 0.2 | 14.9 ± 0.3 | 15.2 ± 0.1 | 15.0 ± 0.4 |

| lPLT x103 (mm3) | 840 ± 54 | 781 ± 39 | 789 ± 29 | 837 ± 39 |

| mMPV (μm3) | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 5.5 ± 0.2 | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 5.3 ± 0.1 |

| nDIFF (%) | ||||

| oLYM | 53.8 ± 3.1 | 47.2 ± 1.4 | 54.7 ± 2.5 | 40.4 ± 1.9 |

| pMON | 10.8 ± 0.3 | 11.1 ± 0.7 | 11.0 ± 0.5 | 10.0 ± 0.7 |

| qGRA | 35.4 ± 3.4 | 41.7 ± 1.4 | 34.3 ± 2.6 | 49.6 ± 2.6 |

Non-immunized male and female Swiss Webster mice consumed peanut butter (100 mg/day, twice a day)

DNP-KLH immunized male and female Swiss Webster mice consumed peanut butter; peanut butter + 100 mg/kg MIDD0301 twice a day, or peanut butter + 5 mg/kg/day prednisone

white blood cells

red blood cells

hemoglobin

hematocrit

mean corpuscular volume

mean cell hemoglobin

mean cell hemoglobin concentration

red cell distribution width

platelets

mean platelet volume

differential white blood cell count

lymphocytes

monocytes

granulocytes

The data is expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 5. ANOVA was used for statistical analysis.

Overall, no significant differences in hematology parameters were found among the four different treatment groups as determined by ANOVA analysis. However, differential lymphocyte values trended lower in the prednisone-treated male and female groups, whereas the differential granulocytes were the highest in these groups. An elevation of granulocytes would be consistent with corticosteroid use in humans where granulocyte (particularly neutrophil) levels are known to increase [26]. Importantly, male and female mice treated with MIDD0301 exhibited differential white blood cells counts similar to the control groups, which are in accord with previously reported hematology ranges for adult Swiss Webster mice [27].

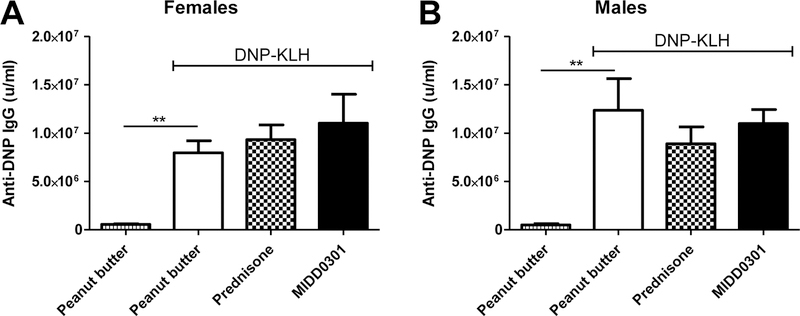

Three groups of female and male mice were immunized with DNP-KLH on days one and 21 of this study. To investigate the effect of MIDD0301 on a T-dependent humoral immune response, serum DNP IgG was measured by ELISA for all mice at day 28 (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Quantification of mouse serum DNP IgG. Swiss Webster male and female mice consumed peanut butter, peanut butter + MIDD0301 (100 mg/kg, twice a day) or peanut butter + prednisone (5 mg/kg/day). DNP-KLH immunization occurred on days 1 and 21, and DNP-specific IgG was quantified on day 28. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 5. ANOVA analysis was used for statistical analysis. ** = P < 0.01.

As expected, DNP-KLH immunization significantly increased DNP-specific IgG in female and male mice (Fig. 6). IgG levels were similar for the DNP-KLH-immunized mice, irrespective of their treatments. Thus, repeat MIDD0301 at 100 mg/kg twice a day did not impair systemic immune function as measured by a secondary antibody response to a classic T-dependent antigen.

Although pharmacokinetic parameters of MIDD0301 have been reported [5], we further investigated the clearance of MIDD0301 when given chronically by quantifying the average concentration of MIDD0301 in faeces and urine. Here, urine and faeces from MIDD0301-treated male and female mice were collected and quantified by LCMS/MS. The average recovery of unmodified MIDD0301 in urine at day 28 was 46.9 ± 11.6 mg per liter of urine (113.0 ± 27.9 μM) and in faeces 349 ± 78.2 mg per kilogram of faeces (841.0 ± 188.6 μmol/kg). Thus, the majority of MIDD0301 is excreted via faeces.

Discussion

Immunotoxicity evaluations are an essential part of preclinical studies to evaluate drug candidates before first in human trials. MIDD0301 is a small molecule developed for the oral treatment of asthma, effective in reducing airway constriction and airway inflammation. In an ovalbumin-induced murine model of asthma, administration of MIDD0301 was able to reduce the number of bronchoalveolar leukocytes that include eosinophils, macrophages and CD4+ T cells [5]. The mode of action of MIDD0301 is novel, targeting GABAARs of leukocytes and ASM. It has been shown that resting and activated T cells express different subtypes of GABAARs [29]; thus selective GABAAR targeting therapeutics can be anti-inflammatory without inducing general suppression of the immune system.

MIDD0301 modulates the transmembrane potential of T cells, which may directly or indirectly reduce the release of intercellular calcium, as shown for GABAAR ligand XHE-III-74 acid [30]. In turn, calcium homeostasis mediates the immune response of T cells [31]. To probe further the influence of MIDD0301 on systemic immunity, high doses of MIDD0301 (100 mg/kg) were administered orally twice a day. Differential white cell counts demonstrated no changes in the number and ratio of lymphocytes, monocytes and granulocytes in the blood of MIDD0301-treated compared to vehicle-treated animals. Furthermore, lymphoid organs (spleen and thymus) and Peyer’s patches were unchanged by treatment as determined by organ weight and histology. This is an important finding, because oral dosing of other anti-inflammatory agents such as dexamethasone are known to induce severe apoptosis of intestinal lymphatic tissue and reduce the numbers of Peyer’s patches [32]. Our results are consistent with this observation, where prednisone treatment caused reduced spleen and thymus mass in both female and male mice. Female and male mice were immunized with DNP-KLH to determine if MIDD0301 caused systemic immune suppression. DNP-specific antibody quantification showed that consumption of MIDD0301 twice a day for 28 days did not diminish this T-dependent response.

Pharmacokinetic experiments in mice with orally administered MIDD0301 have shown a high AUC of 84.0 μM/h in serum (t1/2 = 13.9 hr) and 56.0 μM/h in lung tissue (t1/2 = 3.9 hr) following a 25 mg/kg dose [5]. In addition, we have reported that MIDD0301 is very stable in the presence of human and mouse liver microsomes, with half-lives of 25.7 and 9.2 hr, respectively. We report herein that the concentration of unchanged MIDD0301 in faeces and urine is below 10% of the administered daily dose; consistent with the hypothesis that phase II metabolism plays an important role in MIDD0301 clearance. Similarly low renal secretion has been shown for unchanged NSAID bearing a carboxylic acid function and substantial hepatic conjugation has been reported.[33] Future studies will investigate the phase II metabolism of MIDD0301.

Taken together, we have demonstrated that MIDD0301 induces no adverse immunotoxicological effects in mice at 100 mg/kg twice a day over a period of 28 days. The production of specific antibodies following DNP-KLH immunization was not diminished by MIDD0301, although in an ovalbumin-induced model of asthma, MIDD0301 reduced the number of lung leukocytes [5]. Accordingly, MIDD0301 acts as an anti-inflammatory agent that selectively reduces inflammation in the lung without compromising systemic immune function. Finally, these studies show that MIDD0301 is a safer alternative to prednisone, where 5 mg/kg/day prednisone (2.5% of the MIDD0301 dose) for 28 days in mice reduced spleen and thymus masses, altered spleen morphology and reduced animal weight.

Acknowledgement:

We thank Dr. Beryl R. Forman and Jennifer L. Nemke (Animal Facility at UWM) for their guidance and support.

Funding Sources. This work was supported by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, the National Institutes of Health R03DA031090 (L.A.A.), R01NS076517 (J.M.C., L.A.A.), R01HL118561 (J.M.C., L.A.A., D.C.S.), R01MH096463 (J.M.C., L.A.A.) as well as the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee Research Foundation (Catalyst grant), the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, the Richard and Ethel Herzfeld Foundation.

Abbreviation:

- IND

investigational new drug

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- DNP-KLH

dinitrophenol-keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- GABAAR

GABAA receptor

- AHR

airway hyperresponsiveness

- CNS

central nervous system

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- HRMS

high resolution mass spectrometry

- NSAID

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- EDTA

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: Drs. Li, Cook, Stafford and Arnold are authors of patent application WO2018035246A1 “Gaba(A) receptor modulators and methods to control airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation in asthma. Stafford and Arnold have equity interests in Pantherics Incorporated, which has certain intellectual property rights to these patents.

References

- 1.Myers TR. Guidelines for asthma management: a review and comparison of 5 current guidelines. Respir Care 2008;53:751–67; discussion 67–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raundhal M, Morse C, Khare A, Oriss TB, Milosevic J, Trudeau J, et al. High IFN-gamma and low SLPI mark severe asthma in mice and humans. The Journal of clinical investigation 2015;125:3037–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schumann C, Kropf C, Wibmer T, Rudiger S, Stoiber KM, Thielen A, et al. Omalizumab in patients with severe asthma: the XCLUSIVE study. The clinical respiratory journal 2012;6:215–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abonia JP, Putnam PE. Mepolizumab in eosinophilic disorders. Expert review of clinical immunology 2011;7:411–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forkuo GS, Nieman AN, Kodali R, Zahn NM, Li G, Rashid Roni MS, et al. A Novel Orally Available Asthma Drug Candidate That Reduces Smooth Muscle Constriction and Inflammation by Targeting GABAA Receptors in the Lung. Mol Pharm 2018;15:1766–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olsen RW, Sieghart W. GABA(A) receptors: Subtypes provide diversity of function and pharmacology. Neuropharmacology 2009;56:141–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sieghart W Chapter Three - Allosteric Modulation of GABAA Receptors via Multiple Drug-Binding Sites. Adv Pharmacol 2015;72:53–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. https://wwwproteinatlasorg/ENSG00000187730-GABRD/tissue.

- 9.Fu XW, Wood K, Spindel ER. Prenatal nicotine exposure increases GABA signaling and mucin expression in airway epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2011;44:222–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiang YY, Wang SH, Liu MY, Hirota JA, Li JX, Ju W, et al. A GABAergic system in airway epithelium is essential for mucus overproduction in asthma. Nature Medicine 2007;13:862–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallos G, Yim P, Chang S, Zhang Y, Xu D, Cook JM, et al. Targeting the restricted alpha-subunit repertoire of airway smooth muscle GABAA receptors augments airway smooth muscle relaxation. American journal of physiology Lung cellular and molecular physiology 2012;302:248–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yocum GT, Turner DL, Danielsson J, Barajas MB, Zhang Y, Xu D, et al. GABAA receptor alpha4-subunit knockout enhances lung inflammation and airway reactivity in a murine asthma model. American journal of physiology Lung cellular and molecular physiology 2017;313:L406–L15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanders RD, Grover V, Goulding J, Godlee A, Gurney S, Snelgrove R, et al. Immune cell expression of GABAA receptors and the effects of diazepam on influenza infection. J Neuroimmunol 2015;282:97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yocum GT, Perez-Zoghbi JF, Danielsson J, Kuforiji AS, Zhang Y, Li G, et al. A Novel GABAA Receptor Ligand MIDD0301 with Limited Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration Relaxes Airway Smooth Muscle Ex Vivo and In Vivo. American journal of physiology Lung cellular and molecular physiology 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15. http://wwwichorg/products/guidelines/safety/safety-single/article/immunotoxicity-studies-for-human-pharmaceuticalshtml.

- 16.Kojima F, Frolov A, Matnani R, Woodward JG, Crofford LJ. Reduced T cell-dependent humoral immune response in microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 null mice is mediated by nonhematopoietic cells. J Immunol 2013;191:4979–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tveden-Nyborg P, Bergmann TK, Lykkesfeldt J. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology Policy for Experimental and Clinical studies. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2018;123:233–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnold LA, Stafford D, Cook CM, Emala CW, Forkuo GS, Jahan R, et al. GABA(A) receptor modulators and methods to control airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation in asthma WO2018/035246 A1. 2018.

- 19.Forkuo GS, Nieman AN, Yuan NY, Kodali R, Yu OB, Zahn NM, et al. Alleviation of Multiple Asthmatic Pathologic Features with Orally Available and Subtype Selective GABAA Receptor Modulators. Mol Pharm 2017;14:2088–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown AP, Dinger N, Levine BS. Stress produced by gavage administration in the rat. Contemporary topics in laboratory animal science 2000;39:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Meijer VE, Le HD, Meisel JA, Puder M. Repetitive orogastric gavage affects the phenotype of diet-induced obese mice. Physiology & behavior 2010;100:387–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balcombe JP, Barnard ND, Sandusky C. Laboratory routines cause animal stress. Contemporary topics in laboratory animal science 2004;43:42–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang L, Lee NJ, Nguyen AD, Enriquez RF, Riepler SJ, Stehrer B, et al. Additive actions of the cannabinoid and neuropeptide Y systems on adiposity and lipid oxidation. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism 2010;12:591–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.CFW (Swiss Webster mice) strain code: 024 Charles River description.

- 25.Hassan NM, Neiman RS. The pathology of the spleen in steroid-treated immune thrombocytopenic purpura. American journal of clinical pathology 1985;84:433–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dale DC, Fauci AS, Guerry DI, Wolff SM. Comparison of agents producing a neutrophilic leukocytosis in man. Hydrocortisone, prednisone, endotoxin, and etiocholanolone. The Journal of clinical investigation 1975;56:808–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Serfilippi LM, Pallman DR, Russell B. Serum clinical chemistry and hematology reference values in outbred stocks of albino mice from three commonly used vendors and two inbred strains of albino mice. Contemporary topics in laboratory animal science 2003;42:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meneton P, Ichikawa I, Inagami T, Schnermann J. Renal physiology of the mouse. American journal of physiology Renal physiology 2000;278:F339–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bjurstom H, Wang J, Ericsson I, Bengtsson M, Liu Y, Kumar-Mendu S, et al. GABA, a natural immunomodulator of T lymphocytes. J Neuroimmunol 2008;205:44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forkuo GS, Guthrie ML, Yuan NY, Nieman AN, Kodali R, Jahan R, et al. Development of GABAA Receptor Subtype-Selective Imidazobenzodiazepines as Novel Asthma Treatments. Mol Pharm 2016;13:2026–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monaco S, Jahraus B, Samstag Y, Bading H. Nuclear calcium is required for human T cell activation. J Cell Biol 2016;215:231–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruiz-Santana S, Lopez A, Torres S, Rey A, Losada A, Latasa L, et al. Prevention of dexamethasone-induced lymphocytic apoptosis in the intestine and in Peyer patches by enteral nutrition. Jpen-Parenter Enter 2001;25:338–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davies NM, Skjodt NM. Choosing the right nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug for the right patient: a pharmacokinetic approach. Clinical pharmacokinetics 2000;38:377–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Besnard J, Ruda GF, Setola V, Abecassis K, Rodriguiz RM, Huang XP, et al. Automated design of ligands to polypharmacological profiles. Nature 2012;492:215–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang XP, Mangano T, Hufeisen S, Setola V, Roth BL. Identification of human Ether-a-go-go related gene modulators by three screening platforms in an academic drug-discovery setting. Assay and drug development technologies 2010;8:727–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]