Abstract

Existing research indicates that justice-involved individuals use a variety of different drugs and polysubstance use is common. Research shows that different typologies of drug users, such as polydrug users versus users of a single drug, have differing types of individual-, structural-, and neighborhood-level risk characteristics. However, little research has been conducted on how different typologies of drug use are associated with HIV risks among individuals in community corrections and their intimate sex partners. This paper examines the different types of drug use typologies among men in community correction programs and their female primary sex partners. We used latent class analysis to identify typologies of drug use among men in community correction programs in New York City and among their female primary sex partners. We also examined the associations between drug use typologies with sexual and drug use behaviors that increase the risk of HIV acquisition. The final analysis included a total of 1167 participants (822 male participants and 345 of their female primary sex partners). Latent class analyses identified three identical typologies of drug use for both men and their female primary sex partners: (1) polydrug use, (2) mild polydrug users with severe alcohol and marijuana use, and (3) alcohol and marijuana users. Men and women who were classified as polydrug users and mild polydrug users, compared to those who were classified as alcohol and marijuana users, tended to be older and non-Hispanic Caucasians. Polydrug users and mild polydrug users were also more likely to have risky sex partners and higher rates of criminal justice involvement. There is a need to provide HIV and drug use treatment and linkage to service and care for men in community correction programs, especially polydrug users. Community correction programs could be the venue to provide better access by reaching out to this high HIV risk key population with increased rates of drug use and multiple sex partners.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11524-018-0265-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Drug use, Criminal justice, HIV, Sexual risk behaviors

Introduction

With close to 7 million people under some form of state or federal supervision (i.e., community corrections, probation, parole, jails, and prisons) [1], the USA ranks higher than all other countries in the proportion of its citizens that are incarcerated. More than half of these individuals are under community supervision (i.e., mandated to probation or parole, community courts, or alternative-to-incarceration programs) [1]. In 2015, over 4.5 million adults were in community correction programs, which is approximately equal to 1 in 53 adults in the USA [2]. The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (NCASA) estimates that approximately 70–85% of all offenders have violated drug laws, were intoxicated or high at the time of the offense, committed the offense to support a drug habit, or have a history of drug addiction [3].

Research has consistently shown the close relationship between criminal justice system involvement, drug use, and HIV risk behaviors [4, 5]. The HIV/AIDS epidemic in the USA coincided with the advent of the “war on drugs” and a sharp rise in mandatory minimum sentencing [4]. As a result, many drug-using individuals at high risk for HIV are also at high risk for criminal justice involvement (CJI). Although there is a lack of reliable large-scale epidemiologic data on HIV prevalence among community correction populations [6], a small number studies have found HIV prevalence rates as high as 13–17% among this population [7, 8], and it has been estimated that 17–25% of people living with HIV/AIDS in the USA pass through the criminal justice system annually [9]. Although most research on criminal justice populations has focused on prisons or jails, one of the greatest periods of risk for HIV transmission is when these individuals are living in the community [4, 10, 11].

Existing research indicates that justice-involved individuals use a variety of different drugs and polysubstance use is common [12, 13]. Polysubstance use is the use of more than two substances over a defined time frame (90 days in this study). The Drug Abuse Monitoring program, which measured the extent of drug and alcohol use among people arrested in 39 cities across the USA, found that more than 70% of arrestees tested positive for at least one of five drugs (i.e., cocaine, marijuana, opiates, methamphetamine, or phencyclidine (PCP)), and more than 20% tested positive for multiple drugs in both 1999 and 2003 [14, 15]. Of all study sites, New York City had the highest rate of inmates testing positive for any of the five drugs—79.9% for males and 74.9% for females—compared with a median of 64.2% for males and 62.5% for females tested in the other US cities [16].

Research shows that different typologies of drug users, such as polydrug users versus users of a single drug, have differing types of individual-, structural-, and neighborhood-level risk characteristics [17, 18]. For example, polydrug users have been shown to be less likely to engage and remain in drug abuse treatment, especially methadone maintenance therapy, than single drug users [19]. Polydrug use has been shown to complicate HIV prevention and intervention [20]. Injection drug users who use multiple drugs have been found to have higher levels of HIV-related risky drug and sexual behaviors than single drug users, such as being more likely to share needles [21] and have more casual sex partners and a greater involvement in sex trading [22].

Polydrug use has been found to increase the odds of involvement in the criminal justice system [23]. Polydrug users have also been found to be more likely to be unemployed, divorced, or separated, and have lower levels of education than single drug users [17]. Studies of heterosexual drug-using couples suggest differentiated gender risks [24–26]. Women may have less ability than men to control the circumstances of their drug use, including procurement of drugs, using and sharing drugs, and ability to inject [27, 28]. Women frequently use drugs in the context of close relationships, including intimate sexual relationships [24, 29].

Despite the extremely high prevalence of drug use among individuals in community correction programs, little research has been conducted on how different typologies of drug use are associated with HIV risks among this population or among their intimate sex partners. Identifying drug use typologies of individuals in community correction programs and their associated risky drug and sexual behaviors may help guide the design of targeted interventions and services for this population and may also help inform HIV and drug treatment and services and improve clinical outcomes [30, 31]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine different types of drug use typologies among men in community correction programs and their female primary sex partners. This study used latent class analysis (LCA) to identify typologies of drug use among men in community correction programs in New York City and that of their female primary sex partners. We also examine the associations between drug use typologies with sexual and drug use behaviors that place one at risk for HIV/AIDS. We examine whether the typologies are associated with sociodemographics (e.g., age and ethnicity), sex, and drug risks, and structural factors such as unemployment and types of criminal justice charges. We speculate that both men and their female primary sex partners who fall in the typologies of polydrug use may report greater sexual risks.

Methods

Design and Study Population

Male participants were screened to participate in a randomized controlled trial to assess the effectiveness of a couple-based HIV prevention intervention—Project PACT, Protect and Connect—among drug-involved men in community correction programs and their female primary sex partners. Male participants were recruited from different community correction programs including the Center for Court Innovation, Bronx Community Solutions (BCS), Fortune, Exodus, and Department of Probation (DOP) sites in New York City. To be eligible to be screened for Project PACT, participants had to be (1) male, (2) age 18 or older, (3) have a female sexual or intimate partner, and (4) be on probation or reporting to BCS or within the past 90 days. Eligible male participants were asked to refer their female partners for study participation.

Procedures

Trained research assistants (RAs) approached male clients at community correction programs after they were sentenced and gave them flyers briefly describing the study. If a man indicated that he was interested in participating in the study, the RA completed informed consent procedures and conducted a screening interview to determine study eligibility. Once the potential participant’s eligibility was established, he was asked to invite his female primary sex partner to participate. The main female sex partner was then consented and screened. The interview with the female partner was conducted, on average, within a month of the male partner’s interview. The majority of women were interviewed within 2–7 days of their male partner. When we interviewed the female partner, we verified that she was indeed the primary sex partner of the male participant by asking several questions (e.g., how many people did they have vaginal or anal sex with, in the past year, besides their main partner). This yielded a total sample of 1209 individuals, with 845 males and 364 female partners. The Columbia University IRB approved all study activities.

Measures

During screening, male participants and their female primary sex partners separately completed a face-to-face interview that was approximately 20 min in length. The interview elicited detailed information on sociodemographic characteristics (i.e., age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education level, employment status, and location of residence), drug and alcohol use history, sexual behaviors, sexual partner characteristics, and incarceration history. Although the male participants and their female partners reported their own characteristics and behaviors, each was asked questions about their perception of their partner’s characteristics and sexual and drug risk behaviors.

Individual Characteristics

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Screening participants were asked about their age and their race/ethnicity. Participants could select one or more race/ethnicity categories. Any participant who reported that they were Black/African American (even if they also selected additional racial/ethnic categories) was coded as “Black” for the analysis. All participants who did not report that they were Black/African American were coded as “Non-Black.” Participants were also asked about their marital status (i.e., single, married, separated/widowed/divorced), whether they were currently employed, had children under the age of 18 years old, and their annual household income.

Drug Use and Alcohol Use

Male participants and their female partners were asked if they had ever used illicit drugs and whether they used in the past 90 days. This included all forms of ingestion of heroin, cocaine, crack, marijuana, crystal meth, ecstasy, non-prescribed methadone, and non-therapeutic use of stimulants, barbiturates, amphetamines, or opiates. Each was also asked about alcohol use and misuse (e.g., ever drank alcohol or binge drank (had five or more alcoholic beverages on one occasion) in the past 90 days).

Sexual and Drug Risk Behaviors

Male participants and their female partners were asked how many sex partners they had in the past year in addition to their primary sex partners, and the number of times they had unprotected vaginal sex in the past year. They were also asked if they had been diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the past year. In addition, we inquired about their perceptions of their main partner’s HIV risks in the past year (i.e., had sex with another partner, injected drugs, shared a syringe with someone in the past year, had an STI, or was HIV positive) or perpetrated severe partner violence in the past year.

Structural Characteristics

Criminal Justice History

Participants were asked whether they had been required to report to community court, an alternative-to-incarceration (ATI) program, drug treatment court, mental health court, or were on probation or parole in the past 90 days. They were also asked if they had been charged with a misdemeanor in the past year.

Employment History

Participants were asked to categorize their current employment status based on the following categories: not employed, employed part-time, and employed full-time.

Drug and Alcohol Treatment

Participants were asked whether they attended an alcohol or drug treatment program in the past 90 days.

Statistical Analysis

To categorize and identify potential typologies of drug use among individuals in community correction programs and their association with alcohol use history, sociodemographic characteristics, employment, incarceration history, sexual risk behaviors, sexual partner, and structural characteristics, we conducted a LCA using the screener data.

The benefit of using LCA to define typologies of substance use variables is that with the exploration of latent classes, we are able to define unobserved groups in the sample that form unique and informative subgroups in responses to their substance use patterns [32]. Such an exploration into the unobserved similarity in substance use patterns would not be sufficiently detected in a simple dichotomization of substance use variables, as individuals would be slotted into groups that are defined by a single behavior or symptom instead of multiple symptoms or patterns. Considering that substance use is a construct comprised of multiple behaviors and is not a unitary phenomenon, the use of LCA allows us to identify the different combination of behaviors that can define substance use.

To assess the differential typologies of drug use among the study sample, we conducted separate analyses for males and females in this sample. We used 11 dichotomous variables on drug history indicating the use of alcohol, marijuana, crack, ecstasy, sedatives, methamphetamines, heroin, methadone, opiates, uppers, and other injectable drugs in the last 90 days to classify latent classes.

To assess class fit, we compared models with varying number of latent classes upon Akaike information criteria (AIC), Bayesian information criteria (BIC), sample-size-adjusted Bayesian information criteria (SSBIC), entropy values (a measure of individual classification based on posterior probabilities), and bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT). The final model was selected based on model fit statistics, consistency with literature findings, and interpretability [33, 34]. Specifically, we decided the final model based on (1) significant results of the BLRT test, (2) smallest SSBIC fit statistics, (3) percent of sample in each derived class (> 5% of the total sample), and (4) entropy values (> 0.60).

Additionally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess if there were significant differences in emergent class bases on the male participants’ recruitment of a female partner. We found that the final substance use typologies did not significantly differ between those male participants that recruited a female partner and those that did not. As such, the final analysis was conducted with all male participants, regardless of female partner recruitment status. For additional information regarding sensitivity analysis, please contact the author.

Upon identifying the optimal number of latent classes, we conducted and reported post hoc one-way ANOVA for individual, structural, and community factors to further characterize the typologies of drug use clusters separately among male participants and their primary female sex partners.

To assess the predictive validity of the derived typologies upon aforementioned individual and structural factors, we conducted a binomial logistic regression. In this analysis, we examined whether differential patterns in substance use typology (i.e., derived classes) by gender-predicted sociodemographic characteristics, sexual and drug risk behaviors, criminal justice involvement, employment status, and alcohol or drug treatment by drug cluster. All analyses were conducted using Mplus version 8 [35].

Results

We observed incremental improvement in several model fit indices (BLRT/SSBIC/AIC) from one to two classes solutions for both male participants and their female primary sex partners (Supplemental Table 1a and 1b). Crucially, however, despite having comparable fit indices (BLRT and SSBIC), the four-class solution for both males and females yielded a delineation of classes with less than 5% of the sample (i.e., 1.05 and 3.1%, respectively), indicating a poor delineation and fit of classes [33, 36]. The three-class model was also interpretable and made theoretical sense. Together, these considerations strongly argued that the three-class model was the best fitting solution for both male participants and their female primary sex partners. For greater detail on the individual characteristics of each group, refer to Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristic of sample.

| Polydrug users (Poly; n = 54) | Mild polydrug users with severe alcohol and marijuana use (M-Poly; n = 248) | Alcohol and marijuana users (AM; n = 520) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Alcohol and drug use1 | ||||||

| Alcohol | 534 | (45.8) | 403 | (49.0) | 131 | (38.0) |

| Marijuana | 537 | (46.0) | 387 | (47.1) | 150 | (43.3) |

| Crack/cocaine | 124 | (10.6) | 77 | (9.4) | 47 | (13.6) |

| Ecstasy | 38 | (3.3) | 31 | (3.8) | 7 | (2.0) |

| Sedatives/tranquilizers | 62 | (5.3) | 45 | (5.5) | 17 | (4.9) |

| Methamphetamines | 3 | (0.3) | 2 | (0.2) | 1 | (0.3) |

| Heroin | 82 | (7.0) | 55 | (6.7) | 27 | (7.8) |

| Methadone2 | 34 | (2.9) | 24 | (2.9) | 10 | (2.9) |

| Opiate-based drugs2 | 76 | (6.5) | 60 | (7.3) | 16 | (4.6) |

| Stimulants2 | 10 | (0.9) | 7 | (0.9) | 3 | (0.9) |

| Injected drugs | 49 | (4.2) | 33 | (4.0) | 16 | (4.6) |

| Alcohol and drug use3 | ||||||

| Alcohol | 719 | (61.6) | 526 | (64.0) | 193 | (55.9) |

| Marijuana | 878 | (75.2) | 624 | (75.9) | 254 | (73.6) |

| Crack/cocaine | 293 | (25.1) | 188 | (22.9) | 105 | (30.4) |

| Ecstasy | 195 | (16.7) | 145 | (17.6) | 50 | (14.5) |

| Sedatives/tranquilizers | 105 | (9.0) | 81 | (9.9) | 24 | (7.0) |

| Methamphetamines | 27 | (2.3) | 17 | (2.1) | 10 | (2.9) |

| Heroin | 153 | (13.1) | 105 | (12.8) | 48 | (13.9) |

| Methadone1 | 71 | (6.1) | 49 | (6.0) | 22 | (6.4) |

| Opiate-based drugs1 | 145 | (12.4) | 113 | (13.7) | 32 | (9.3) |

| Stimulants1 | 51 | (4.4) | 41 | (5.0) | 10 | (2.9) |

| Injected drugs | 87 | (7.5) | 58 | (7.1) | 29 | (8.4) |

| Sociodemographic | ||||||

| Age, mean(SD) | 32.7 | (12.5) | 32.5 | (12.4) | 33.2 | (12.5) |

| Black | 602 | (51.6) | 421 | (51.2) | 181 | (52.5) |

| White | 59 | (5.1) | 34 | (4.1) | 25 | (7.2) |

| Total sample n = 1167 | Males n = 822 | Females n = 345 | ||||

| Drug risk behaviors | ||||||

| Shared syringe2 | 30 | (2.6) | 17 | (2.1) | 13 | (3.8) |

| Sexual partner | ||||||

| Age, mean(SD) | 31.88 | (12.1) | 30.7 | (11.8) | 34.6 | (12.4) |

| Black | 534 | (45.8) | 336 | (40.9) | 198 | (57.4) |

| White | 66 | (5.7) | 59 | (7.2) | 7 | (2.0) |

| IPV4 | 49 | (4.2) | 38 | (4.7) | 11 | (3.2) |

| Other sexual partner | 510 | (43.7) | 346 | (42.1) | 164 | (47.5) |

| Injected drugs | 102 | (8.7) | 69 | (8.4) | 33 | (9.6) |

| STI+ | 53 | (4.5) | 29 | (3.5) | 24 | (7.0) |

| HIV+ | 73 | (6.3) | 48 | (5.8) | 25 | (7.2) |

| Criminal justice involvement | ||||||

| Misdemeanor3 | 497 | (42.6) | 451 | (54.9) | 46 | (13.3) |

| Community court4 | 211 | (18.1) | 191 | (23.2) | 20 | (5.8) |

| Probation3 | 722 | (61.9) | 687 | (83.6) | 35 | (10.1) |

| Mandated to receive services3 | 207 | (17.7) | 183 | (22.3) | 24 | (7.0) |

| ATI2,5 | 179 | (15.3) | 156 | (19.0) | 23 | (6.7) |

| Employment | ||||||

| Unemployed | 826 | (70.8) | 581 | (70.7) | 245 | (71.0) |

| Alcohol or drug treatment1 | ||||||

| Attended drug or alcohol treatment program | 217 | (18.6) | 181 | (22.0) | 36 | (10.4) |

| Borough | ||||||

| Bronx | 497 | (42.6) | 352 | (42.8) | 145 | (42.0) |

| Brooklyn | 385 | (33.0) | 284 | (34.5) | 101 | (29.3) |

| Manhattan | 236 | (20.2) | 156 | (19.0) | 80 | (23.2) |

| Queens | 38 | (3.3) | 23 | (2.8) | 15 | (4.3) |

| Staten Island | 11 | (0.9) | 7 | (9.0) | 4 | (1.2) |

1Past 90 days

2Not prescribed by a doctor

3Lifetime

4IPV—in the past year, has your main sexual partner threatened you with a lethal weapon, choked you, constantly prevented you from seeing friends or family or going out without him/her, or constantly stalked you?

5Alternative-to-incarceration

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Total Sample

The final analysis includes a total of 1167 participants (822 male participants and 345 of their female primary sex partners). Of the total sample, 40.8% recruited their female partners for this the study. Among the male samples, 51.2% were Black/African American, 4.1% were non-Hispanic Caucasian, 25.9% were Hispanic, and the average age was 32.53 years old (SD = 12.42). Among the female primary sex partners in the sample, 52.5% were Black/African American, 7.2% were non-Hispanic Caucasian, 25.2% were Hispanic, and the average age was 33.23 years old (SD = 12.53).

Male Participants’ Descriptive and Bivariate Analysis

Almost half (49%) reported using alcohol in the past 90 days, 47.1% marijuana, 9.4% crack/cocaine, 7.3% used non-prescribed opiates, 6.7% heroin, 3.8% ecstasy, 2.9% non-prescribed methadone, 0.9% non-prescribed stimulants, 0.3% sedatives/tranquilizers, 0.2% crystal meth/methamphetamines, and 4% reported injecting drugs. Sexual and drug risk behaviors were evident as 9.4% reported having had an STI in the past year, 1.5% reported being HIV positive, and 2.1% shared syringes in the past year. On average, the male participants had sex with 4.11 (SD = 6.86) women other than their female primary sex partner in the last year, and on average, they reported having had unprotected sex in the past year with 1.16 (SD = 4.02) female partners other than their female primary sex partner. Of the male partners’ reports of their female primary sex partner’s characteristics, the majority said that their female primary sex partner was Black/African American (40.9%). Only 7.2% had a non-Hispanic Caucasian primary sexual partner. Male partners reported that in the past year, 42.1% of their primary female partners had sex with another male, 8.4% injected drugs, 3.5% had an STI, 5.9% reported that she was HIV positive, and 11.5% report experiencing IPV perpetrated by their female sex partner in the past year. Criminal justice involvement among the sample of male participants found that the majority were on probation (83.6%), 22.3% were required by a judge to receive services, 54.9% were charged with a misdemeanor in the past year, 23.2% were required by a judge to attend community court in the past 90 days, and 19% were in ATI programs in the past 90 days. Of all the male participants in the sample, 22% attended a drug or alcohol treatment program in the past 90 days and 70.7% were unemployed at time of the study interview.

Female Primary Sex Partner Participants’ Descriptive and Bivariate Analysis

Based on finding from the screening interviews with the female primary sex partners, 38% reported alcohol use, 43.3% reported marijuana use, 13.6% reported crack/cocaine use, 2% reported ecstasy use, 4.9% reported use of sedatives/tranquilizers, 0.3% reported crystal meth/methamphetamine use, 7.8% reported use of heroin, 2.9% reported non-prescribed use of methadone, 4.6% reported non-prescribed use of opiates, 0.9% reported non-prescribed use of stimulants, and 4.6% reported injection drug use in the past 90 days. As to the sexual and drug risk behaviors among the female primary sex partners of men in the sample, the prevalence of self-reported STIs among the women was 17.1%, the HIV prevalence was 3.77%, and 3.8% shared syringes in the past year. On average, females in the sample had sex with 2.83 men (SD = 16.35) other than their primary sexual partner in the past year and, on average, had unprotected sex with 0.47 men (SD = 1.323) other than their primary sexual partner during this time period. Based on data from the female sex partners of men in the study, the men had the following characteristic: 57.4% were Black/African American, 2% were non-Hispanic Caucasian, and the average age of a male partner was 34.56 years old (SD = 12.387), 47.5% had sex with someone other than the female primary partner in the past year, 9.6% injected drugs, 7% of the men had had an STI in the past year, 7.2% were HIV positive, and 3.2% of the women reported that they had experienced severe IPV from their male partner. Among the female primary sex partners, 10.1% were on probation during the past 90 days, 7% were required by a judge to receive services, 13.3% were charged with a misdemeanor in the past year, 5.8% were required by a judge to attend community court in the last 90 days, and 6.7% were in ATI programs. Of the females in the sample, 10.4% attended a drug or alcohol treatment program during the past 90 days and 71% were unemployed at time of the interview.

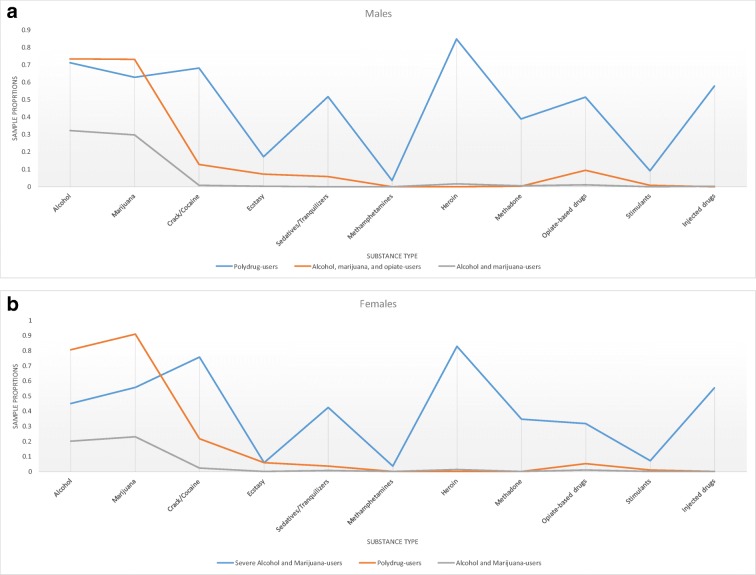

Clusters of Drug Use for Male Participants

We identified three drug typologies among the male participants: (1) polydrug users, (2) mild polydrug users with severe alcohol and marijuana use, and (3) alcohol and marijuana users (Table 2). Among the total sample of men (n = 822), we found that 6.6% were polydrug users (n = 54), 30.2% were mild polydrug users with severe alcohol and marijuana use (n = 248), and the majority of the sample were classified as alcohol and marijuana users (n = 520; 63.3%) Fig. 1a.

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics of three latent classes of male substance users

| Polydrug users (Poly; n = 54) | Mild polydrug users with severe alcohol and marijuana use (M-Poly; n = 248) | Alcohol and marijuana users (AM; n = 520) | Class comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Alcohol and drug use1 | |||||||

| Binge drinking alcohol | 39 | 72.222 | 219 | 88.306 | 145 | 27.885 | M-Poly > Poly > AM |

| Marijuana | 34 | 62.963 | 219 | 88.306 | 134 | 25.769 | M-Poly > Poly > AM |

| Crack/cocaine | 38 | 70.370 | 39 | 15.726 | 0 | 0.000 | Poly > M-Poly > AM |

| Ecstasy | 9 | 16.667 | 22 | 8.871 | 0 | 0.000 | Poly > M-Poly > AM |

| Sedatives/tranquilizers | 28 | 51.852 | 17 | 6.855 | 0 | 0.000 | Poly > M-Poly > AM |

| Methamphetamines | 2 | 3.704 | 0 | 0.000 | 0 | 0.000 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Heroin | 47 | 87.037 | 0 | 0.000 | 8 | 1.538 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Methadone2 | 22 | 40.741 | 0 | 0.000 | 2 | 0.385 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Opiate-based drugs2 | 28 | 51.852 | 28 | 11.290 | 4 | 0.769 | Poly > M-Poly > AM |

| Stimulants2 | 5 | 9.259 | 2 | 0.806 | 0 | 0.000 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Injected drugs | 32 | 59.259 | 0 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.192 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Sociodemographic | |||||||

| Age, mean(SD) | 41.67 | 11.317 | 30.46 | 11.4 | 32.58 | 12.582 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Black | 17 | 31.481 | 135 | 54.435 | 269 | 51.731 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| White | 11 | 20.370 | 6 | 2.419 | 17 | 3.269 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Sexual and drug risk behaviors | |||||||

| Number of sexual partners, mean(SD) | 2.93 | 2.338 | 5.60 | 9.262 | 3.50 | 5.419 | M-Poly > Poly and AM |

| Number of unprotected sexual partners, mean(SD) | 1.24 | 1.704 | 1.80 | 6.449 | 0.83 | 2.201 | M-Poly > AM |

| Self-reported crabs | 0 | 0.000 | 4 | 1.613 | 0 | 0.000 | M-Poly > AM |

| Shared syringe3 | 11 | 20.370 | 3 | 1.210 | 3 | 0.577 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Sexual partner characteristics | |||||||

| Age, mean(SD) | 37.98 | 11.575 | 28.82 | 11.134 | 30.91 | 11.851 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Black | 13 | 24.074 | 109 | 43.952 | 214 | 41.154 | Poly < M-Poly and AM |

| White | 14 | 25.926 | 19 | 7.661 | 26 | 5.000 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| IPV4 | 3 | 5.556 | 13 | 5.242 | 22 | 4.231 | Not significant |

| Other sex partner | 30 | 55.556 | 127 | 51.210 | 189 | 36.346 | Poly and M-Poly > AM |

| Injected drugs | 26 | 48.148 | 18 | 7.258 | 25 | 4.808 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| STI+ | 14 | 25.926 | 6 | 2.419 | 9 | 1.731 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| HIV+ | 4 | 7.407 | 20 | 8.065 | 24 | 4.615 | |

| Criminal justice involvement | |||||||

| Misdemeanor3 | 37 | 68.519 | 144 | 58.065 | 270 | 51.923 | Not significant |

| Community court1 | 26 | 48.148 | 79 | 31.855 | 86 | 16.538 | Poly > M-Poly > AM |

| Probation1 | 37 | 68.519 | 191 | 77.016 | 459 | 88.269 | Poly and M-Poly >AM |

| Required to receive services1 | 24 | 44.444 | 68 | 27.419 | 91 | 17.500 | Poly > M-Poly > AM |

| ATI5 | 22 | 40.741 | 40 | 16.129 | 94 | 18.077 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Parole1 | 3 | 5.556 | 10 | 4.032 | 25 | 4.808 | Not significant |

| Employment | |||||||

| Unemployed | 44 | 81.481 | 188 | 75.806 | 349 | 67.115 | M-Poly> AM |

| Alcohol or drug treatment1 | |||||||

| Attended drug or alcohol treatment program | 29 | 53.704 | 38 | 15.323 | 114 | 21.923 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Borough | |||||||

| Bronx | 27 | 50.000 | 126 | 50.806 | 119 | 22.885 | Not significant |

| Brooklyn | 6 | 11.111 | 67 | 27.016 | 211 | 40.577 | Not significant |

| Manhattan | 17 | 31.481 | 49 | 19.758 | 90 | 17.308 | Not significant |

| Queens | 2 | 3.704 | 6 | 2.419 | 15 | 2.885 | Not significant |

| Staten Island | 2 | 3.704 | 0 | 0.000 | 5 | 0.962 | Not significant |

1Past 90 days

2Not prescribed by a doctor

3Past year

4IPV—in the past year, has your main sexual partner threatened you with a lethal weapon, choked you, constantly prevented you from seeing friends or family or going out without him/her, or constantly stalked you?

5Alternative-to-incarceration

Fig. 1.

a Three latent classes of males in community supervision programs by type of substance use. b Three latent classes of females in community supervision programs by type of substance use

There was a significant difference between classes on age (F(2, 819) = 18.850, p < 0.001), race/ethnicity, specifically on rates of African American (F(2, 671) = 7.719, p < 0.001) and non-Hispanic Caucasians (F(2, 671) = 18.877, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed that those males in the polydrug-using class were significantly less likely to be African American and significantly more likely to be older and non-Hispanic Caucasian when compared to mild polydrug users and alcohol- and marijuana-using classes. There was no significant difference between clusters on the number of individuals of Hispanic descent.

There was a significant difference between classes on number of sexual partners (F(2, 804) = 8.823, p < 0.001), number of unprotected sexual partners other than their primary sexual partner (F(2, 804) = 4.868, p < 0.001), needle sharing (F(2, 819) = 54.099, p < 0.001), and rates of crabs (F(2, 671) = 4.646, p = 0.010) in the past year. Specifically, post hoc analysis revealed that those males in the mild polydrug-using class were significantly more likely to have multiple sexual partners when compared to polydrug-using and alcohol- and marijuana-using classes. Males in the mild polydrug-using class were also significantly more likely to have greater number of unprotected sexual partners and higher rates of self-reported crabs when compared to the alcohol- and marijuana-using class, but not significantly different than those in the polydrug-using class. Finally, males in the polydrug-using class were significantly more likely to share needles in the past year when compared to the two other classes.

The primary female partners of the men significantly differed by class in age (F(2, 799) = 13.730, p < 0.001) and race/ethnicity, specifically on rates of African American (F(2, 652) = 5.317, p = 0.005) and non-Hispanic Caucasians (F(2, 652) = 15.127, p < 0.001). Specifically, post hoc analysis indicated that those female partners with a male partner in the polydrug-using class were significantly more likely to be older and non-Hispanic Caucasian, while being significantly less likely to be African American when compared to mild polydrug-using and alcohol- and marijuana-using classes. There was also a significant difference between primary female partners upon having sex with someone outside of their relationship (F(2, 819) = 9.960, p < 0.001), had history of injection drug use (F(2, 819) = 70.066, p < 0.001), and having an STI in the past year (F(2, 819) = 47.492, p < 0.001). Specifically, those primary female partners with male partners in the alcohol- and marijuana-using class were significantly less likely to have sex with someone outside of their relationship when compared to the polydrug-using and mild polydrug-using classes. Additionally, those female partners with male partners in the polydrug-using class were significantly more likely to have had history of injection drug use and an STI in the past year when compared to the alcohol- and marijuana-using and mild polydrug-using classes. There were no significant differences between the three drug clusters on the male partner self-reported HIV status of the female sex partner and on experiencing IPV perpetrated by the female partner (i.e., threatened them with a weapon in the past year, choked them, stalked them, etc.).

There was a significant difference between classes upon rates of probation in the past 90 days (F(2, 819) = 12.866, p < 0.001), mandate by a judge to receive services (F(2, 819) = 13.364, p < 0.001), judge required community court in the past 90 days (F(2, 819) = 22.157, p < 0.001), and enrollment in an ATI program (F(2, 819) = 9.281, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed that males in the alcohol- and marijuana-using class were significantly more likely to be on probation in the past 90 days when compared to mild polydrug-using and polydrug-using classes. Males in the polydrug-using class were significantly more likely to be mandated by a judge to receive services and attend community court in the past 90 days, and enroll in an ATI program when compared to alcohol- and marijuana-using and mild polydrug-using classes. Additionally, males in the mild polydrug-using class were significantly more likely to be mandated by a judge to receive services and attend community court in the past 90 days when compared to the alcohol- and marijuana-using class. There was no significant difference between classes on misdemeanor charges in the past year and rates of parole in the past 90 days.

There was a significant difference between classes on unemployment (F(2, 819) = 4.724, p = 0.009), such that males in the mild polydrug-using class were significantly more likely to be unemployed when compared to the alcohol- and marijuana-using class. There was a significant difference between classes on seeking drug or alcohol treatment program in the past 90 days (F(2, 819) = 19.876, p < 0.001), such that post hoc analysis revealed males in the polydrug-using class were significantly more likely to seek these services when compared to the other two classes.

Predictive Validity of Male Drug Clusters

A binomial logistic regression was performed to ascertain the predictive validity of drug use typologies among males based upon individual and structural factors. The model for individual difference in self-reported HIV (χ2(2) = 25.236, p < 0.0001) and Caucasian race (χ2(2) = 8.610, p = 0.014) was significant. Males with positive self-reported HIV were significantly more likely to be in the polydrug-using and mild polydrug-using classes when compared to alcohol- and marijuana-using class. Additionally, those in the polydrug class were significantly more likely to self-report positive HIV status when compared to the other two classes. Caucasians were significantly more likely to be in the alcohol- and marijuana-using class than non-Caucasians.

The model for criminal justice history difference in mandated reporting to a community court (χ2(2) = 25.236, p < 0.0001), enrollment in alternative-to-incarceration program (χ2(2) = 25.236, p < 0.0001), court supervision (χ2(2) = 25.236, p < 0.0001), probation (χ2(2) = 25.236, p < 0.0001), and parole (χ2(2) = 25.236, p < 0.0001) was significant. Specifically, those in the alcohol- and marijuana-using class were significantly less likely to be mandated to report to a community court, enrolled in TI program, or be in court supervision. Men in the polydrug-using class were significantly more likely to be on probation and parole than not on probation or parole.

Those who said that they shared syringes in the past year (χ2(2) = 23.322, p < 0.0001) were significantly more likely to be in the polydrug use and mild polydrug use class than those that did not share syringes in the past year. Those who were unemployed (χ2(2) = 9.602, p = 0.008) were significantly more less likely to be in the alcohol- and marijuana-using class than those who were employed. All other variables were not significant predictors of drug cluster among males (p > 0.05).

Female Drug Use Clusters

Data gathered through interviews with the female sample primary sex partners found that, similar to the males, female partner drug use could be clustered in three ways: (1) polydrug users, (2) mild polydrug users with severe alcohol and marijuana use, and (3) alcohol and marijuana users (Table 3). Among the 345 females in the sample, we found that 8.4% were polydrug users (n = 29), 25.5% were mild polydrug users with severe alcohol and marijuana use (n = 88), and a majority of females (66.1%; n = 228) were alcohol and marijuana users Fig. 1b.

Table 3.

Descriptive characteristics of two latent classes of female substance users

| Polydrug users (Poly; n = 29) | Mild polydrug users with severe alcohol and marijuana use (M-Poly; n = 88) | Alcohol and marijuana users (AM; n = 228) | Class comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Alcohol and drug use1 | |||||||

| Binge drinking alcohol | 13 | 44.83 | 80 | 90.91 | 38 | 16.67 | M-Poly > Poly > AM |

| Marijuana | 16 | 55.17 | 83 | 94.32 | 51 | 22.37 | M-Poly > Poly > AM |

| Crack/cocaine | 22 | 75.86 | 22 | 25.00 | 3 | 1.32 | Poly > M-Poly > AM |

| Ecstasy | 2 | 6.90 | 5 | 5.68 | 0 | 0.00 | Poly & M-Poly >AM |

| Sedatives/tranquilizers | 13 | 44.83 | 3 | 3.41 | 1 | 0.44 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Methamphetamines | 1 | 3.45 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Heroin | 24 | 82.76 | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 1.32 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Methadone2 | 10 | 34.48 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Opiate-based drugs2 | 10 | 34.48 | 5 | 5.68 | 1 | 0.44 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Stimulants2 | 2 | 6.90 | 1 | 1.14 | 0 | 0.00 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Injected drugs | 16 | 55.17 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Sociodemographic | |||||||

| Age, mean(SD) | 40 | 11.158 | 33.78 | 12.849 | 32.15 | 12.334 | Poly > AM |

| Black | 12 | 41.38 | 50 | 56.82 | 119 | 52.19 | Not significant |

| White | 6 | 20.69 | 5 | 5.68 | 14 | 6.14 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Sexual and drug risk behaviors | |||||||

| Number of sexual partners, mean(SD) | 3.66 | 3.384 | 2.47 | 4.204 | 2.86 | 19.923 | Not significant |

| Number of unprotected sexual partners, mean(SD) | 1.90 | 2.795 | .57 | 1.403 | .25 | .784 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Self-reported herpes | 3 | 10.34 | 1 | 1.14 | 6 | 2.63 | Poly > M-Poly |

| Self-reported HIV positive | 2 | 6.90 | 8 | 9.09 | 6 | 2.63 | M-Poly > AM |

| Self-reported STI | 10 | 34.48 | 17 | 19.32 | 32 | 14.04 | Poly > AM |

| Shared syringe3 | 11 | 37.93 | 1 | 1.14 | 1 | 0.44 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Sexual partner characteristics | |||||||

| Age, mean(SD) | 45.24 | 8.305 | 34.95 | 12.188 | 33.04 | 12.254 | Poly > AM |

| Black | 15 | 10.34 | 54 | 61.36 | 129 | 56.58 | Not significant |

| White | 4 | 6.90 | 2 | 2.27 | 1 | 0.44 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| IPV4 | 3 | 34.48 | 3 | 3.41 | 5 | 2.19 | Not significant |

| Other sex partner | 19 | 37.93 | 48 | 54.55 | 97 | 42.54 | Not significant |

| Injected drugs | 18 | 10.34 | 4 | 4.55 | 11 | 4.82 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| STI+ | 7 | 6.90 | 5 | 5.68 | 12 | 5.26 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| HIV+ | 6 | 34.48 | 6 | 6.82 | 13 | 5.70 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Criminal justice involvement | |||||||

| Misdemeanor3 | 12 | 41.38 | 11 | 12.50 | 23 | 10.09 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Community court1 | 6 | 20.69 | 2 | 2.27 | 12 | 5.26 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Probation1 | 3 | 10.34 | 12 | 13.64 | 20 | 8.77 | Not significant |

| Required to receive services1 | 5 | 17.24 | 4 | 4.55 | 15 | 6.58 | Not significant |

| ATI5 | 4 | 13.79 | 5 | 5.68 | 14 | 6.14 | Not significant |

| Parole1 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 2.27 | 0 | 0.00 | M-Poly > AM |

| Employment | |||||||

| Unemployed | 29 | 100.00 | 68 | 77.27 | 148 | 64.91 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Alcohol or drug treatment1 | |||||||

| Attended drug or alcohol treatment program | 10 | 34.48 | 9 | 10.23 | 17 | 7.46 | Poly > M-Poly and AM |

| Borough | |||||||

| Bronx | 13 | 44.83 | 32 | 36.36 | 100 | 43.86 | Not significant |

| Brooklyn | 2 | 6.90 | 26 | 29.55 | 73 | 32.02 | Not significant |

| Manhattan | 13 | 44.83 | 27 | 30.68 | 40 | 17.54 | Not significant |

| Queens | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 3.41 | 12 | 5.26 | Not significant |

| Staten Island | 1 | 3.45 | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 1.32 | Not significant |

1Past 90 days

2Not prescribed by a doctor

3Past year

4IPV—in the past year, has your main sexual partner threatened you with a lethal weapon, choked you, constantly prevented you from seeing friends or family or going out without him/her, or constantly stalked you?

5Alternative-to-incarceration

There was a significant difference between classes on age (F(2, 342) = 5.297, p = 0.005), race/ethnicity, specifically on rates of non-Hispanic Caucasians (F(2, 283) = 3.743, p = 0.025). Post hoc analysis revealed that those females in the polydrug-using class were significantly more likely to be non-Hispanic Caucasian when compared to mild polydrug users and alcohol- and marijuana-using classes. Additionally, females in the polydrug user class were significantly older than those in the alcohol and marijuana user class. There was no significant difference between clusters on the number of females of African American or Hispanic descent.

There was a significant difference between classes on number of unprotected sexual partners other than their primary sexual partner (F(2, 339) = 35.565, p < 0.001), needle sharing (F(2, 342) = 71.768, p < 0.001), rates of herpes (F(2, 283) = 2.999, p = 0.051) in the past year, HIV-positive status (F(2, 283) = 3.479, p = 0.032), and having any STI (F(2, 342) = 4.058, p = 0.018). Specifically, post hoc analysis revealed that females in the polydrug-using class were significantly more likely to have greater number of unprotected sexual partners and endorse needle sharing when compared to mild polydrug-using and alcohol- and marijuana-using classes. Additionally, females in the polydrug-using class were significantly more likely to have any form of STI when compared to alcohol- and marijuana-using class, but not the mild polydrug-using class. Females in the mild polydrug-using class had significantly higher rates of self-reported herpes and being HIV positive when compared to the alcohol and marijuana user class, but not the polydrug-using class. There was no significant difference in number of sexual partners between classes.

The primary male partners of the women significantly differed by class in age (F(2, 341) = 13.434, p < 0.001) and race/ethnicity, specifically on rates of non-Hispanic Caucasians (F(2, 282) = 11.283, p < 0.001). Specifically, post hoc analysis indicated that those male partners with a female partner in the polydrug-using class were significantly more likely to be older and non-Hispanic Caucasian when compared to mild polydrug-using and alcohol- and marijuana-using classes. There was also a significant difference between primary male partners upon having history of injection drug use (F(2,342) = 70.687, p < 0.001), having an STI in the past year (F(2, 342) = 7.479, p = 0.001), and self-reported HIV status of the male sex partner (F(2, 334) = 4.491, p = 0.012). Specifically, those primary male partners with female partners in the polydrug-using class were significantly more likely to have had history of injection drug use, an STI in the past year, and positive self-reported HIV status when compared to the two other classes. There were no significant differences between the three drug clusters on the primary male partner on sex with someone outside of their relationship and experiencing IPV perpetrated by the male partner (i.e., threatened them with a weapon in the past year, choked them, stalked them, etc.).

There was a significant difference between classes upon misdemeanor charges in the past year (F(2, 342) = 11.574, p < 0.001) and judge required community court in the past 90 days (F(2, 342) = 7.178, p = 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed that females in the polydrug-using class were significantly more likely have been charged with a misdemeanor and required to attend community court when compared to mild polydrug-using and alcohol- and marijuana-using classes. There was no significant difference between classes on rates of probation in the past 90 days, mandate by a judge to receive services, enrollment in an ATI program, and rates of parole in the past 90 days.

There was a significant difference between classes on unemployment (F(2, 342) = 9.212, p < 0.001), such that females in the polydrug-using class were significantly more likely to be unemployed when compared to the two other class. There was a significant difference between female classes on seeking drug or alcohol treatment program in the past 90 days (F(2, 342) = 10.586, p < 0.001), such that post hoc analysis revealed females in the polydrug-using class were significantly more likely to seek these services when compared to the other two classes.

Predictive Validity of Female Drug Clusters

A binomial logistic regression was performed to ascertain the predictive validity of drug use typologies among females based upon individual and structural factors. The model for individual difference in self-reported HIV (χ2(2) = 22.398, p < 0.001) and Caucasian race (χ2(2) = 5.937, p = 0.051) was significant. Females with positive self-reported HIV were significantly more likely to be in the polydrug-using and mild polydrug-using classes when compared to alcohol- and marijuana-using class. Additionally, those in the polydrug class were significantly more likely to self-report positive HIV status when compared to the other two classes. Caucasians were significantly more likely to be in the mild polydrug-using class than non-Caucasians.

The model for criminal justice history difference was significant for mandated reporting to a community court (χ2(2) = 6.012, p = 0.049). Specifically, those in the polydrug-using class were significantly more likely to be mandated to report to a community court. Those who were unemployed (χ2(2) = 143.538, p < 0.001) were significantly more less likely to be in the polydrug-using class than those who were employed. Additionally, females who had self-reported being positive for an STI (χ2(2) = 9.027, p < 0.011) were significantly more likely to be in the polydrug-using class than those who did not report having an STI. All other variables were not significant predictors of drug cluster among females (p > 0.05).

Discussion

Although extensive research has been done on the relationship between polydrug use and HIV, this paper addresses a significant gap in the literature by describing the typologies of drug use and their correlates (e.g., sociodemographics, sexual and drug risks, and structural characteristics) among men in community corrections and their female primary sex partners. More than half of the males and their female sex partners in this study were African American, a small percentage of the sample were non-Hispanic Caucasian (less than 10%), and the participants were slightly over 30 years of age for both genders. The sociodemographic characteristics in this study are generally consistent with what is known about men in community correction programs in New York City, although our sample had a smaller proportion of non-Hispanic Caucasians (4.1%) than those under custody in New York City (24.7%) [37].

Overall, the prevalence of reported recent illicit drug use (such as heroin, crack, cocaine, and other opioids) in this study among both men and women was remarkably lower than what we expected. The drug with the greatest prevalence of use reported by both genders was crack, where women reported a slightly higher prevalence of the use of this drug in the past 90 days than the men. Moreover, we found that nearly half of both genders in this study reported current use of marijuana. We offer two potential explanations for the low reports of current illicit use of multiple drugs in our study. First, men in this study may have underreported drug use because admitting to currently using drugs while they are in community correction programs may legally jeopardize their status and result in harsher criminal punishment. Second, reporting current use of marijuana, which is decriminalized in New York State, may be perceived as less serious as it does not have the same legal consequences compared to reporting use of other illicit drugs.

Latent class analyses identified three identical typologies of drug use for both men and their female primary sex partners: (1) polydrug use, (2) mild polydrug users with severe alcohol and marijuana use, and (3) alcohol and marijuana use among men and women. Our findings show that there are a number of significant correlates associated with the typologies for both genders. Men and women who were classified as polydrug users, compared to those who were classified as other types of users, tended to be older and non-Hispanic Caucasians. We found that age was a significant predictor of drug use group among men and women in this sample, such that older individuals were significantly more likely to be in the polydrug use group. Furthermore, we found that among both males and females, non-Hispanic Caucasians were significantly more likely to be in the polydrug use cluster than other racial/ethnic groups. Though we lack definitive data on reasons for participants’ arrest, our findings indicate that people of color, and primarily Black/African American individuals, are arrested for marijuana possession and other minor drug charges more frequently than non-Hispanic Caucasians, which is consistent with what has been extensively shown in New York City and across the USA [38–42].

Our results have significant implications for HIV/STI prevention and intervention. Female partners who had a male partner in the polydrug use group were significantly more likely to have a history of injection drug use and to have had an STI than females who did not have a male partner in the polydrug use group. Additionally, females who were in the polydrug-use group had higher numbers of unprotected sex partners than women in the other groups. Males who had a female partner in the polydrug-use group were significantly more likely to be HIV positive, have a history of injection drug use, and have had an STI in the past year. These findings are consistent with the literature showing polydrug users have higher sexual risks compared to their counterparts [22, 43, 44]. These results indicate that HIV prevention and intervention programs should focus on couples where one or both partners are polydrug users.

Individuals in the polydrug use groups in this study were found to have distinct characteristics in criminal justice history and employment. As expected, participants in the polydrug use cluster generally had higher rates of criminal justice involvement than participants in the other groups. Male polydrug users were significantly more likely to be mandated to receive services by a judge, attend community court, or attend an alternative-to-incarceration (ATI) program in the past 90 days than males in other groups. Although the female partners were not recruited as clients from the community correction programs, a significant number of them also reported some history of criminal justice system involvement. Female polydrug users were significantly more likely to have committed a misdemeanor or attend community court in the past 90 days than females who were not polydrug users. The majority of both genders in the study were unemployed; however, female polydrug users had a higher prevalence of unemployment than those in other groups (100 vs. 67.3%). While it is difficult for any individual coming out of community corrections to find employment, our findings indicate that it may be particularly challenging for female polydrug users to find a job, and they may require additional intervention strategies (such as connection to opioid substitution therapy or other drug treatment services) in order to successfully transition back to the community.

The study has a number of limitations that need to be mentioned. Male participants were not recruited randomly, but were a self-selected sample. Moreover, not all the male participants recruited their female partners into the study; thus, the female primary sex partners may not represent all female partners of men in community correction programs. Furthermore, male participants recruited their female partners (who indicated that they were the primary sexual partner) and whether the male participants “forced” their female primary sex partners to participate in the study is unknown. Additionally, the sample size of non-Hispanic Caucasians in this study is small, as is the size of the polydrug-use cluster. Moreover, no drug testing was done. Drug use was assessed based on self-reported data. Moreover, drug use variables are used as dichotomous variables without measuring the severity of drug use. Furthermore, we have not included any biological measures for substance use, HIV, HCV, or STIs, so our prevalence estimates are likely conservative. Furthermore, while the use of LCA has been well substantiated as a means to study substance use typologies, advances in statistical modeling have suggested the use of a hybrid approach using LCA and item response theory (IRT) to better understand the multidimensional nature of substance use symptoms and behaviors [45].

Future research should pay more attention to addressing the above limitations in order to produce more robust typologies of drug users and their correlates. This research is critically needed, given the growing population of people in community correction programs.

Despite these limitations, there are distinct strengths of this study and the analytical methods used. The use of LCA allows us to better define unobserved typologies of substance use behaviors that would have otherwise been lost if we relied upon traditional methods [46]. Furthermore, this study not only provided insight into the different typologies of drug use by gender, but also tested the predictive validity of those classes upon classifying individual and structural factors.

Conclusion

xFindings from this study have important drug use and HIV prevention implications. There is a pressing need to provide HIV and drug use treatment and linkages to service and care for men in community correction programs with a strong attention to polydrug users. More targeted attention should be given to polydrug users to prevent HIV risk behaviors and link people to HIV and drug use services and care. Community correction programs could be the venue to provide better access by reaching out to this high HIV risk key population with increased rates of drug use and multiple sex partners. Given that the men were willing to recruit and successfully bring in their female primary sex partners to participate in the study, a couple-based HIV prevention approach and linkage to drug use services may be appropriate, where both can receive the intervention together. Couple-based approaches may serve this population well, given that both drug-using clusters and both genders reported significant risks for HIV and continued drug usex.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 18 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the assistance of the Center for Court Innovation and the New York City Department of Probation for supporting the implementation of this study, and want to particularly thank the men and women who participated in this study.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (grant R01DA033168). Dr. Davis is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (T32 grant MH019139 and P30 grant MH043520) and Mr. Marotta is supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (T32 grant DA037801).

References

- 1.Kaeble D, Glaze L, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Correctional Populations in the United States, 2015. In. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice; 2016.

- 2.Kaeble D, Bonczar T, Bureau of Justice Statistics . Probation and Parole in the United States, 2015. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Califano Jr, JA. Behind bars: Substance abuse and America's prison population. New York, NY: National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University (CASA), January 1998. Available online at http://www.casacolumbia.org/Absolutenm/articlefiles/5745.pdf. Accessed 15 Sept 1999.

- 4.Clark C, McCullumsmith C, Waesche M, Islam M, Francis R, Cropsey K. HIV-risk characteristics in community corrections. J Addict Med. 2013;7(1):45–51. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3182781806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maruschak L, Beavers R. HIV in prisons, 2007–2008. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larney S, Hado S, McKenzie M, Rich J. Unknown quantities: HIV, viral hepatitis, and sexually transmitted infections in community corrections. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41(4):283. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belenko S, Langley S, Crimmins S, Chaple M. HIV risk behaviors, knowledge, and prevention education among offenders under community supervision: a hidden risk group. AIDS Educ Prev. 2004;16(4):367–385. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.4.367.40394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis A, Dasgupta A, Goddard-Eckrich D, El-Bassel N. Trichomonas vaginalis and human immunodeficiency virus coinfection among women under community supervision: a call for expanded T. vaginalis screening. Sex Transm Dis. 2016;43(10):617–622. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spaulding A, Seals R, Page M, Brzozowski A, Rhodes W, Hammet THIV. AIDS among inmates of and releases from US correctional facilities, 2006: declining share of epidemic but persistent public health opportunity. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braithwaite R, Arriola K. Male prisoners and HIV prevention: a call for action ignored. Am J Public Health. 2008;93:759–763. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.5.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blankenship K, Smoyer A. Between spaces: understanding movement to and from prison as an HIV risk factor. In: Sanders B, Thomas Y, Deeds B, editors. Crime, HIV and health: intersections of criminal justice and public health concerns. Dordrecht: Springer; 2013. pp. 207–221. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark B, Perkins A, McCullumsmith C, Islam A, Sung J, Cropsey K. What does self-identified drug of choice tell us about individuals under community corrections supervision? J Addict Med. 2012;6:57–67. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e318233d603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cropsey K, Stevens E, Valera P, et al. Risk factors for concurrent use of benzodiazepines and opioids among individuals under community corrections supervision. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;154:152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freudenberg N. HIV in the epicenter of the epicenter: HIV and drug use among criminal justice populations in new York City, 1980–2007. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46:159–170. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.521460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Z. Drug and alcohol use and related matters among arrestees, 2003. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring . 2000 arrestee drug abuse monitoring: annual report. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinotti G, Carli V, Tedeschi D, di Giannantonio M, Roy A, Janiri L, Sarchiapone M. Mono and polysubstance dependent subjects differ on social factors, childhood trauma, personality, suicidal behaviour, and comorbid Axis I diagnoses. Addict Behav. 2009;34(9):790–793. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Racz S, Saha S, Trent M, et al. Polysubstance use among minority adolescent males incarcerated for serious offenses. Child Youth Care Forum. 2016;45(2):205–220. doi: 10.1007/s10566-015-9334-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monga N, Rehm J, Fischer B, Brissette S, Bruneau J, el-Guebaly N, Noël L, Tyndall M, Wild C, Leri F, Fallu JS, Bahl S. Using latent class analysis (LCA) to analyze patterns of drug use in a population of illegal opioid users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearson F, Cleland C, Chaple M, Hamilton Z, Prendergast M, Rich J. Substance use, mental health problems, and behavior at risk for HIV: evidence from CJDATS. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40(4):459–469. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrell P, Mancha B, Petras H, Trenz R, Latimer W. Latent classes of heroin and cocaine users predict unique HIV/HCV risk factors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;122(3):220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meacham M, Rudolph A, Strathdee S, et al. Polydrug use and HIV risk among people who inject heroin in Tijuana, Mexico: a latent class analysis. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50:1351–1359. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.1013132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Betts K, Chan G, McIlwraith F, et al. Differences in polysubstance use patterns and drug-related outcomes between people who inject drugs receiving and not receiving opioid substitution therapies. Addiction. 2016;111:1214–1223. doi: 10.1111/add.13339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnard M. Needle sharing in context: patterns of sharing among men and women injectors and HIV risks. Addiction. 1993;88(6):805–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bryant J, Brener L, Hull P, Treloar C. Needle sharing in regular sexual relationships: an examination of serodiscordance, drug using practices, and the gendered character of injecting. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;107(2):182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Syvertsen J, Robertson A, Strathdee S, Martinez G, Rangel M, Wagner K. Rethinking risk: gender and injection drug-related HIV risk among female sex workers and their non-commercial partners along the Mexico-US border. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(5):836–844. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cleland C, Des Jarlais D, Perlis T, Stimson G, Poznyak V. HIV risk behaviors among female IDUs in developing and transitional countries. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):271. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Go V, Quan V, Voytek C, Celentano D, Nam L. Intra-couple communication dynamics of HIV risk behavior among injecting drug users and their sexual partners in northern Vietnam. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;84(1):69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cruz M, Mantsios A, Ramos R, et al. A qualitative exploration of gender in the context of injection drug use in two U.S.-Mexico border cities. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(2):253–262. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9148-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Callaghan R, Brands B, Taylor L, et al. The clinical characteristics of adolescents reporting methamphetamine as their primary drug of choice: an examination of youth admitted to inpatient substance-abuse treatment in northern British Columbia, Canada, 2001–2005. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:286–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suh J, Ruffins S, Robins C, et al. Self-medication hypothesis: connecting affective experience and drug choice. Psychoanal Psychol. 2008;25:518–532. doi: 10.1037/0736-9735.25.3.518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muthén B. Latent variable analysis. The Sage handbook of quantitative methodology for the social sciences. Thousands oaks: SAGE; 2004. p. 345–368.

- 33.Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct Equ Model. 2007;14(4):535–569. doi: 10.1080/10705510701575396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muthén B. Statistical and substantive checking in growth mixture modeling: comment on Bauer and Curran (2003). Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus. The comprehensive modelling program for applied researchers: user’s guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2015. p. 5.

- 36.Celeux G, Soromenho G. An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. J Classif. 1996;13(2):195–212. doi: 10.1007/BF01246098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.New York State Corrections and Community Supervision. Under custody report: profile of under custody population as of January 1, 2016. Albany, NY; Department of Corrections and Community Supervision; 2016.

- 38.Ramchand R, Pacula R, Iguchi M. Racial differences in marijuana-users’ risk of arrest in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;84(3):264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Golub A, Johnson B, Dunlap E. The race/ethnicity disparity in misdemeanor marijuana arrest in New York City. Criminol Public Policy. 2007;6(1):131–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9133.2007.00426.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White K, Holman M. Marijuana prohibition in California: racial prejudice and selective arrests. Race, Gender Class. 2012;19(3/4):75–92. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson B, Golub A, Dunlap E, Sifaneck S. An analysis of alternatives to New York City’s current marijuana arrest and detention policy. Policing: Int J Police Strat Manag. 2008;31(2):226–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Austin W, Ressler R. Who gets arrested for marijuana use? The perils of being poor and black. Appl Econ Lett. 2017;24(4):211–213. doi: 10.1080/13504851.2016.1178838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kokkevi A, Kanavou E, Richardson C, Fotiou A, Papadopoulou S, al e. Polydrug use by European adolescents in the context of other problem behaviours. Nordic Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;31(4):323–342. doi: 10.2478/nsad-2014-0026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Connor J, Gullo M, White A, Kelly A. Polysubstance use: diagnostic challenges, patterns of use and health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27(4):269–275. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muthén B. Should substance use disorders be considered as categorical or dimensional? Addiction. 2006;101(s1):6–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muthén B, Muthén LK. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24(6):882–891. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb02070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 18 kb)