Abstract

Objective

Develop an epidemiological study of injuries occurred among male professional football players during the Copa America 2011, held in Argentina.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of injuries sustained during the 43rd edition of the Copa America football in Argentina, in 2011. The lesions were evaluated by the medical department of the selections and reported to the CONMEBOL. The data were compiled and reported in accordance with rules established by the FIFA Medical Assessment and Research Centre (F-MARC) in 2005.

Results

There was a higher prevalence of lesions in the lower limbs. Thighs and knees were the most affected segments. The most frequent diagnoses were muscle injuries. The injuries were mostly minor degrees of severity and there was little difference in the prevalence of lesions according to the stages of the match, with slight predominance in the final 15 minutes. The incidence of lesions per 1,000 game hours was similar to the average found in the literature.

Conclusions

The results obtained allowed us to outline a profile of the prevalence, distribution per body segment, minute in which occurred and severity of injuries in professional football players of participating teams in the Copa America 2011 in Argentina. The extreme rigor of referees may be partly attributed to the highly competitive nature of international tournaments. However, this results cannot be considered definitive because of the need to be compared to other epidemiological studies with same design using similar concepts and criteria.

Keywords: Athletes Football/injuries Epidemiology

Introduction

Football (soccer) is the most popular type of sport worldwide. It has been estimated that at least 200,000 professional football players and 240 million amateur players practice this sport, which covers all age groups and both genders. It also presents a high injury rate.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Approximately 80% of these individuals are male.6, 7 It is a sport that involves much physical contact and short, fast discontinuous movements such as acceleration, deceleration, changes of direction, jumps and pivots. Because of these characteristics, it presents high numbers of injuries in absolute terms8, 9 and has aroused great interest within the field of sports traumatology.

High-yield sports have gone through many changes over recent years, particularly in relation to increased physical demands and risk of injury. It has been estimated that the incidence of football injuries is around 10-15/1,000 hours of training, and can be four to six times greater during games, depending on the study design and the criteria used for defining and characterizing the injuries.10 This heterogeneity causes difficulty with regard to epidemiological analysis, data gathering and the uniformity of the diagnostic criteria and recovery time.

Methodological variations give rise to significant differences in the results and make conclusions and comparisons between studies very difficult. With the aim of minimizing these discrepancies, a group of specialists at FIFA's Medical Assessment and Research Center (F-MARC) was brought together in 2005 and established a consensus by defining concepts and standard methodology for studies on football injuries.11

Materials and methods

The concept used to defined football injuries was the same as chosen by Fuller et al.11 for the FIFA consensus of 2005, i.e. describing them as any physical complaint sustained by a player that results from training or games, independent of any need for medical care or time off from activities.

The subjects of this investigation were the players in the 12 teams that took part in the 43rd Copa America tournament, which was held in eight cities in Argentina between July 1 and 24, 2011, organized by Conmebol. During this period, the team studied played 26 games and each team participated in a minimum of three games, equivalent to the preliminary phase of the tournament, and a maximum of six games, if they participated in the final or the third-place playoff. The general data on the tournament are gathered together in Table 1.

Table 1.

General data on the tournament.

| Teams participating | 12 |

| Players per team | 23 |

| Goalkeepers per team | 3 |

| Total number of players | 276 |

| Total number of matches | 26 |

| Games with extra time | 3 |

| Minutes played | 2,430 |

| Players injured | 26 |

| Total number of injuries | 63 |

Source: Conmebol

The injuries were evaluated by each team's medical department at the ends of the games. The records containing the data relating to the type of injury, body segment affected, date of occurrence, severity and minute of the game in which they occurred were informed by the teams’ physicians and were complied by a member of the tournament organization. Appendix A on the last page presents FIFA's standard form in Spanish that was used by the physicians during the competition.

The severity of the injuries was subdivided according to the estimated recovery period in days, as follows. Grade I/insignificant: no time off needed; grade II/minimal: 1 to 3 days off; grade III/mild: 4 to 7 days off; grade IV/moderate: 8 to 28 days off; grade V/severe: more than 28 days off; and grade VI/career-terminating.11 The final results from this study were assessed retrospectively and were grouped in accordance with FIFA's methods, including the segment classification, injury mechanism (trauma or overload) and diagnoses (Annex 1).

Results

There were 26 games, played over a 17-day period. Among these, the duration of 23 games was 90 minutes and three games lasted for 120 minutes, thus totaling 2,430 minutes of game. In total, 26 players suffered injuries, accumulating 63 injuries.

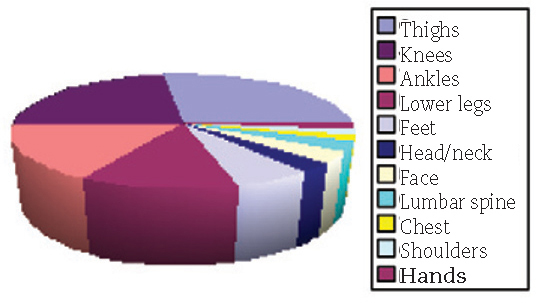

The type of injury most frequently sustained was bruising (25 cases), and the regions most frequently affected were the thighs (17 injuries) and knees (15 injuries). Table 2 and Fig. 1 present the injuries groups according to diagnosis, and Table 3 and Fig. 2 gather together the injuries according to the part of the body affected.

Table 2.

Diagnosis.

| Injury Cases | (n) |

|---|---|

| Bruise | 25 |

| Contracture | 12 |

| Tear | 7 |

| Synovitis | 6 |

| Sprain | 4 |

| Strain | 3 |

| Laceration | 2 |

| Others | 3 |

| Total | 63 |

Source: Conmebol.

Fig. 1.

Diagnoses.

Table 3.

Body segment affected.

| Anatomical location Cases | (n) |

|---|---|

| Thigh | 17 |

| Knee | 15 |

| Ankle | 10 |

| Lower leg | 8 |

| Foot | 4 |

| Head/neck | 2 |

| Face | 2 |

| Lumbar spine | 2 |

| Chest | 1 |

| Shoulder | 1 |

| Hand | 1 |

| Total | 63 |

Fonte: Conmebol.

Fig. 2.

Segment affected.

Among the 26 players injured, 13 (50%) suffered injuries due to contact, while the other 13 (50%) became hurt through indirect trauma. The referees considered that nine of the 13 cases of contact (69%) were fouls, but only one player was sent off.

The Peruvian team did not send in the data relating to the minute of the game at which the injury occurred, nor did they inform the length of time off that these players needed, as estimates for injury severity. In individual terms, four Peruvian players suffered four injuries each, and these were the players who individually presented the greatest numbers of injuries. The Peruvian team was also the one that had the greatest number of injuries, totaling 35. Two Chilean players suffered injuries in the game against Peru and the time during the game at which these occurred was also not informed.

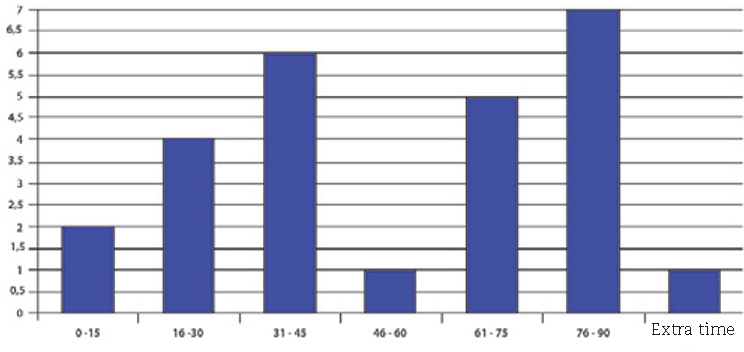

In relation to the minute of the game, 26 injuries were reported. Of these, 13 (50%) occurred during the first half, 12 (46%) occurred during the second half and one (4%) occurred during extra time. The injuries suffered by players of the Peruvian team were excluded from the statistics, because the minute at which they occurred was not specified.

The distribution of the injuries according to severity showed that grade II/minimal injuries (nine cases) were responsible for 32.14% of the total, followed by grade IV/moderate injuries (eight cases), with 28.58%. Grade V/severe injuries (one case) accounted for only 3.58%, thus totaling 28 injuries reported. The Peruvian team was excluded from these statistics because data relating to severity were not provided in detail.

The halves of the game were subdivided into 15-minute periods and extra time. The period with the greatest number of injuries was from the 76th to the 90th minute of the game, with a total of seven injuries (27%). The distribution of the injuries according to period of the game is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Injury distribution according to period of the game.

The estimated number of injuries according to the duration of the activity was 70.7 per 1,000 hours of game, and the incidence of injuries per tournament game was 2.42 over the duration of the competition.

With regard to the prevalence per region of the body, it was seen that 54 (85.7%) of the injuries occurred in the lower limbs and nine (14.3%) occurred elsewhere in the body. Two (3.3%) occurred in the arms, three (4.7%) in the trunk region and four (6.3%) in the head and neck.

Bruises accounted for 39% of all of the injuries (25 in total), followed by muscle contractures with 19% (12 in total). It was noted that nine of the 25 bruises (36%) occurred in the knee, which was the segment most affected. The distribution of these injuries according to body segment is presented in Table 4 and Fig. 4. In relation to muscle contractures, the segment most affected was the thigh, accounting for seven of the 12 injuries (58%), while three (25%) occurred in the calf. The adductor muscles were more frequently involved in the thigh, accounting for three of the seven injuries (43%).

Table 4.

Distribution of bruises according to body segment.

| Segment | Cases |

|---|---|

| Knee | 9 |

| Lower leg | 4 |

| Thigh | 3 |

| Ankle | 2 |

| Foot | 2 |

| Face | 2 |

| Chest | 1 |

| Hand | 1 |

| Shoulder | 1 |

| Total | 25 |

Source: Conmebol.

Fig. 4.

Injury distribution according to period of the game.

Fig. 5 shows the distribution of the injuries according to severity. The incidence of the different types of injury according to the players’ positions on the pitch was not evaluated.

Fig. 5.

Injury distribution according to severity.

Discussion

Several epidemiological studies on the incidence and causes of football injuries have been conducted,1, 2, 5, 7, 11 with the aim of reducing the morbidity in these cases and increasing the players’ safety. Methodological problems relating to these investigations were described in detail by Finch et al.,12 Jung and Dvorak13 and Noyes et al.,14 and these included differences in the concepts used, differences relating to data-gathering and lack of uniformity regarding diagnostic criteria and recovery time. A variety of risk factors and preventive measures have been cited,15, 16, 17 but few groups have investigated the real effectiveness of such measures.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 Previous injuries and inadequate rehabilitation were indicated as risk factors for future injuries by Dvorak et al.15 and Hawkins et al.,28 and up to 25% of the cases are recurrent injuries.29, 30

Younger football players present greater incidence of injuries to the arms, head and face than the average.31 Sullivan et al.32 suggested that the more reckless behavior of these players during sports activities is the main explanation for this finding. In the legs, too, it is noticeable that there is greater incidence of bruises among young players. Most of these are caused by trauma, although it is observed that over the football season, up to 34% of the injuries are due to overload.30

With regard to prevalence according to diagnosis, bruises, strains and sprains are the injuries most frequently encountered in the literature.33, 34, 35 Our study found similar results, given that in addition to showing that leg injuries formed the absolute majority, the types more found were bruises and contractures. Since most of the injuries occurred in the muscles of the thigh and lower leg, the results obtained were concordant, given that they showed that the thigh muscles were the main injury site.

Approximately 28% of the injuries occurred during foul tackles, and this proportion is even higher in international competitions.36 In another study, Fuller et al.37 pointed out that referees consider 47% of the tackles responsible for cases of injury to be fouls. The data gathered in the present study indicate that the referees were more rigorous during the Copa America, such that 69% of these cases were considered to be fouls. Traditionally, it is observed that referees are less tolerant in international games with regard to physical contact between players, although the reasons for this have not been discussed.

Determining the exact time during the game at which injuries occur is also fundamental, given that the great majority of them occur in the first and last 15 minutes of the game.38 In this regard, the present study found similar results, given that most of the injuries occurred during the last 15 minutes of the game. The estimate for the number of injuries according to the duration of the activity was 70.7 for every 1,000 hours of game, and this was compatible with the data in the literature (40-90/1,000 hours of game).10 The large number of injuries observed may reflect greater intensity of the matches because of the extremely competitive nature of tournaments between nations. However, further studies are needed in order to confirm this finding.

The classification of the injury severity generally reflects the length of the player's time off. One model that has traditionally been used30 divides injuries into grades I, II and III, such that grade I includes time off < 7 days, grade II between 7 and 28 days and grade III > 28 days. Another classification that has commonly been used separates injuries into trauma and overload types. Van Mechelen et al.39 defined acute injuries as those that were caused by a single traumatic event and overload injuries as those caused by repetitive microtrauma. The present study was based on the FIFA consensus of 2005, which divides injuries into six categories, and it demonstrated that the majority were classified as mild injuries with time off of no more than three days. This finding is concordant with the general findings in the literature.

It has also been observed in some epidemiological studies that the risk of injury varies from one player to another according to their playing positions.34, 40 However, with the advent of modern football, in which the players hardly maintain fixed positions at all, this situation has changed.

Rev Bras Ortop. 2013;48(2):131-136

This can be confirmed from the studies by Ekstrand et al.5,41 and McMaster et al.,34 which did not find any significant difference in player position with regard to the incidence of injury. Goalkeepers account for the majority of arm injuries, given that this is the only playing position in which these limbs are used to perform the function.42 The present study did not take injured players’ positions into account because of the scarcity of pertinent information.

Certain methodological limitations of the present study need to be pointed out. There is a possibility that the outcome information may have been biased, given that precise data on injuries could have been altered or even omitted by the teams’ physicians. The information obtained in relation to injuries that occurred during games played by the Peruvian team were incomplete, thus making it impossible to include data relating to the time during the game at which the injury occurred and relating to estimated severity according to the time off. The effect of these potential biases of information on the prevalences detected therefore cannot be adequately estimated. Furthermore, the small size of the sample of players and matches and the cross-sectional nature of this study impede establishment of an unequivocal cause-effect relationship. We also emphasize that this was the first study conducted at this level involving Conmebol.

Conclusions

The analysis on the results obtained from the present study made it possible to outline a profile for the prevalence, distribution according to body segment, time of occurrence and severity of injuries among professional football players in the national teams that took part in the Copa America in Argentina in 2011.

The great majority of the findings from this study are concordant with the data obtained from other epidemiological studies involving football injuries. There was greater prevalence of injuries in the lower limbs; the most frequent diagnoses were muscle injuries and most of the injuries were of mild grade of severity. Moreover, injuries occurred slightly more often during the last 15 minutes of the match. These observations indicate that the statistics on such studies have an unvarying and predictable pattern. There was coherence in the data obtained in relation the incidence of injuries per 1,000 hours of game.

However, the referees’ rigor in relation to physical contact between the players was much greater than the average found in the literature. This may reflect discrepancies in the methodology used, between the different studies, as well as suggesting that there is greater intensity and competitiveness in games in tournaments between nations. The conflicting results cannot be considered to be definitive, since they need to be compared with other epidemiological studies that use similar designs and concepts.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there was no conflict of interests in conducting this study.

Footnotes

Work performed in the Sports Medicine Department, Institute of Orthopedics and Traumatology, HC/FMUSP, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil.

References

- 1.Inklaar H. Soccer injuries. Incidence and severity. Sports Med. 1994;18(1):55–73. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199418010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inklaar H. Soccer injuries II. Aetiology and prevention. Sports Med. 1994;18(2):81–93. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199418020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tucker A.M. Common soccer injuries. Diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation. Sports Med. 1997;25(1):21–32. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199723010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoy K., Lindblad B.E., Terkelsen C.J., Helleland H.E., Terkelsen C.J. European soccer injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20(3):318–322. doi: 10.1177/036354659202000314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ekstrand J., Gillquist J. The avoidability of soccer injuries. Int J Sports Med. 1983;4(2):1424–1428. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1026025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Timpka T., Risto O., Bjormsjo M. Boys soccer league injuries: a community-based study of time-loss from sports participation and long-term sequelae. Eur J Public Health. 2008;18(1):19–24. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckm050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Junge A., Dvorak J. Soccer injuries: a review on incidence and prevention. Sports Med. 2004;34(13):929–938. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200434130-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsudo V., Martin V. Lesoes no futebol profissional. Projeto Piloto. Ambito Med Desp. 1995;12:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keller C.S., Noyes F.R., Bencher C.R. The medical aspects of soccer injury epidemiology. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15(3):230–237. doi: 10.1177/036354658701500307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paus V., Torrengo F., Del Compare P. Incidence of injuries in juvenile soccer players. Rev Asoc Argent Traumatol Deporte. 2003;10(1):28–34. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuller C.W., Ekstrand J., Junge A., Andersen T.E., Bahr R., Dvorak J. Consensus statement on injury definitions and data collection procedures in studies of football (soccer) injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:193–201. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2005.025270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finch C.F. An overview of some definitional issues for sports injury surveillance. Sports Med. 1997;24(3):157–163. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199724030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Junge A., Dvorak J. Influence of definition and data collection on the incidence of injuries in football. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(Suppl 5):S40–S46. doi: 10.1177/28.suppl_5.s-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noyes F.R., Lindenfeld T.N., Marshall M.T. What determines an athletic injury (definition)? Who determines an injury (occurrence)? Am J Sports Med. 1988;16(Suppl 1):S65–S68. doi: 10.1177/03635465880160s116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dvorak J., Junge A., Chomiak J., Graf-Baumann T., Peterson L., Rosch D. Risk factor analysis for injuries in football players: possibilities for a prevention program. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(Suppl 5):S69–S74. doi: 10.1177/28.suppl_5.s-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engstrom B.K., Renstrom P.A. How can injuries be prevented in the World Cup soccer athlete? Clin Sports Med. 1998;17(4):755–768. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(05)70116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taimela S., Kujala U.M., Osterman K. Intrinsic risk factors and athletic injuries. Sports Med. 1990;9(4):205–215. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199009040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Askling C., Karlsson J., Thorstensson A. Hamstring injury occurrence in elite soccer players after preseason strength training with eccentric overload. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2003;13(4):244–250. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2003.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caraffa A., Cerulli G., Projetti M., Aisa G., Rizzo A. Prevention of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in soccer: a prospective controlled study of proprioceptive training. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1996;4(1):19–21. doi: 10.1007/BF01565992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ekstrand J., Gillquist J., Liljedahl S.O. Prevention of soccer injuries: supervision by doctor and physiotherapist. Am J Sports Med. 1983;11(3):116–120. doi: 10.1177/036354658301100302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heidt R.S., Jr., Sweeterman L.M., Carlonas R.L., Traub J.A., Tekulve F.X. Avoidance of soccer injuries with preseason conditioning. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(5):659–662. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280050601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hewett T.E., Lindenfeld T.N., Riccobene J.V., Noyes F.R. The effect of neuromuscular training on the incidence of knee injury in female athletes: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(6):699–706. doi: 10.1177/03635465990270060301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Junge A., Rosch D., Peterson L., Graf-Baumann T., Dvorak J. Prevention of soccer injuries: a prospective intervention study in youth amateur players. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(5):652–659. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300050401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandelbaum BR. ACL tears in female athletes: the challenge of prevention with neuromuscular training programs. In: Annual proceedings from the AAOS Meeting: New Orleans, 2003.

- 25.Soderman K., Werner S., Pietila T., Engstrom B., Alfredson H. Balance board training: prevention of traumatic injuries of the lower extremities in female soccer players? A prospective randomized intervention study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8(6):356–363. doi: 10.1007/s001670000147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Surve I., Schwellnus M.P., Noakes T., Lombard C. A fivefold reduction in the incidence of recurrent ankle sprains in soccer players using the Sport-Stirrup orthosis. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(5):601–606. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tropp H., Askling C., Gillquist J. Prevention of ankle sprains. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13(4):259–262. doi: 10.1177/036354658501300408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hawkins R.D., Hulse M.A., Wilkinson C., Hodson A., Gibson M. The association football medical research programme: an audit of injuries in professional football. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35(1):43–47. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.35.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielsen A.B., Yde J. Epidemiology and traumatology of injuries in soccer. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17(6):803–807. doi: 10.1177/036354658901700614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hawkins R.D., Fuller C.W. A prospective epidemiological study of injuries in four English professional football clubs. Br J Sports Med. 1999;33(3):196–203. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.33.3.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoff G.L., Martin A. Outdoor and indoor soccer: injures among youth player. Am J. Sports Med. 1986;14:231–233. doi: 10.1177/036354658601400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sullivan J.A., Gross R.H., Grana W.A., Garcia-Moral C.A. Evaluation of injuries in youth soccer. Am J Sports Med. 1980;8(5):325–327. doi: 10.1177/036354658000800505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt-Olsen S., Bunemann L.K., Lade V., Brass0e J.O. Soccer injuries of youth. Int. J Sports Med. 1985;19(3):161–164. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.19.3.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McMaster W. Injuries in Soccer. Am J Sports Med. 1978;6(6):354–357. doi: 10.1177/036354657800600607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ekstrand J., Nigg N. Surface-related injuries in soccer. Sports Med. 1989;8(1):56–62. doi: 10.2165/00007256-198908010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Junge A., Dvorak J., Graf-Baumann T., Peterson L. Football injuries during Fifa tournaments and the Olympic Games, 1998-2001: development and implementation of an injuryreporting system. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(Suppl 1):80S–90S. doi: 10.1177/0363546503261245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fuller C., Junge A., Dvorak J. An assessment of football referees decisions in incidents leading to player injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(Suppl 1):17S–20S. doi: 10.1177/0363546503261249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahnama N., Reilly T., Lees A. Injury risk associated with playing actions during competitive soccer. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36(5):354–359. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.36.5.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Mechelen W. Sports injury surveillance systems. ‘One size fits all’? Sports Med. 1997;24(3):164–168. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199724030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Engstron B., Johanson C., Tornkusist H. Soccer injuries among elite female players. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:273–275. doi: 10.1177/036354659101900408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]