Abstract

Objective

To analyze retrospectively 309 fractures in the clavicle and the relation with injury of the supraclavicular nerve after trauma.

Methods

It was analyzed 309 patients with 312 clavicle fractures. The Edinburgh classification was used. Four patients had fractures in the medial aspect of the clavicle, 33 in the lateral aspect and 272 in the diaphyseal aspect and three bilateral fractures.

Results

255 patients were analyzed and five had paresthesia in the anterior aspect of the thorax. Four patients had type 2 B2 fracture and one type 2 B1 fracture. All patients showed spontaneous improvement, in the mean average of 3 months after the trauma.

Conclusion

Clavicle fractures and/or shoulder surgeries can injure the lateral, intermediary or medial branches of the supraclavicular nerve and cause alteration of sensibility in the anterior aspect of the thorax. Knowledge of the anatomy of the nerve branches helps avoid problems in this region.

Keywords: Clavicle, Fractures bone, Nerve compression syndromes

Resumo

Objetivo

Analisar retrospectivamente 309 fraturas da clavícula e sua relação com a lesão do nervo supraclavicular após trauma.

Métodos

Foram analisados 309 pacientes com 312 fraturas da clavícula. Foi usada a classificação de Edinburgh. Quatro pacientes apresentavam fraturas da região medial da clavícula, 33 da região lateral, 272 da região diafisária e três com fraturas bilaterais.

Resultados

Foram analisados 255 pacientes e cinco apresentavam parestesia na região anterior do tórax. Quatro pacientes apresentaram fratura do tipo 2 B2 e um do tipo 2 B1. Todos os pacientes tiveram melhoria espontânea, em média de três meses após o trauma.

Conclusão

Fraturas da clavícula e/ou cirurgias no ombro podem lesar os ramos lateral, intermediário ou medial do nervo supraclavicular e causar alteração da sensibilidade na região anterior do tórax. O conhecimento da anatomia dos ramos nervosos ajuda a evitar problemas nessa região.

Palavras-chave: Clavícula, Fraturas ósseas, Síndromes de compressão nervosa

Introduction

Fractures of the clavicle are frequent injuries and are responsible for 2% to 15% of all fractures of the human body and 33% to 45% of the injuries affecting the scapular belt.1, 2, 3, 4 According to the literature, diaphyseal fractures are responsible for 69% to 82% of clavicle fractures and more than half of these present displacement; fractures of the lateral third, for 21% to 28%; and fractures of the middle third, for 2% to 3%.3, 5, 6, 7 There are two peaks of incidence: the first and larger peak is associated with young and active male patients; and the second, with elderly individuals, with slight predominance of females.4, 5, 8

Morphologically, the clavicle has an S shape that results from union between two opposing curves at the level of the middle third. The bone is thin and consequently weak at this union, which is the commonest location for fractures.1, 5, 9

The supraclavicular nerve is a sensory nerve that originates from the C3 and C4 nerve roots of the superficial cervical plexus and divides into medial, intermediate and lateral branches. The nerves form branches in the proximal region of the clavicle and provide sensitivity for the clavicle, anteromedial region of the shoulder and proximal region of the thorax.4, 7 This anatomy makes them particularly vulnerable to injury, in cases of clavicle fracture or during surgical treatment of such fractures.10

The aim of the present study was to retrospectively analyze 309 clavicle fractures and their relationship with injuries to the supraclavicular nerve subsequent to trauma.

Material and methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted on 309 patients with 312 clavicle fractures seen between 2000 and 2010, at Hospital Santa Teresa, Petrópolis. Radiographic assessments were performed using standard radiographs and were based on the Edinburgh classification.5 Among the patients analyzed, four (1%) presented fractures in the medial region of the clavicle, 33 (11%) in the lateral region and 272 (88%) in the diaphyseal region; three patients presented bilateral fractures (Figure 1). There were 219 male patients (71%) and 90 female patients (29%). Their ages ranged from 17 to 67 years, with a mean of 32 years. There were 166 fractures (53%) on the left side and 146 (47%) on the right side.

Figure 1.

Total number of clavicle fractures in the sample, divided according to location.

None of the patients presented any previous fractures of the clavicle. Conservative treatment was used for 277 patients, a sling or orthotic device was used for eight patients, and surgical treatment was used for 32 patients.

Inclusion criteria

Patients were included in this study if they presented a displaced fracture of the diaphysis of the clavicle and were aged over 17 years and under 70 years.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded from this study if they presented: age under 17 years or over 70 years; proximal or distal fractures of the clavicle; fractures without displacement; pathological fractures; exposed fractures; vascular alterations; delayed consolidation or pseudarthrosis; floating shoulder; previous fractures of the clavicle; or cranial trauma.

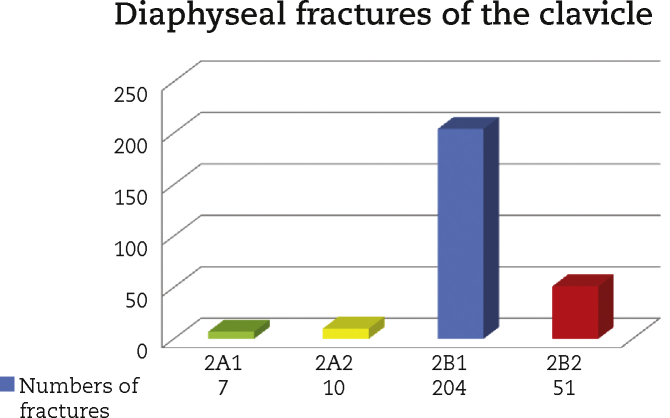

Thus, 255 patients with displaced fractures were included in this study: 204 with type 2 B1 and 51 with type 2 B2 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Diaphyseal fractures of the clavicle divided according to the Edinburgh classification.

For each patient, clinical and radiographic evaluations were performed in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd month after the trauma.

Results

Among the 255 patients analyzed, five reported that they not only had pain and functional incapacity of the affected limb immediately after the trauma, but also had paresthesia on the anterior face of the thorax (Table 1).

Table 1.

Identification of the patients with complaints of paresthesia following diaphyseal fracture of the clavicle.

| Sex and age | Type of injury and side | Classification | Treatment | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 y; M | (RPS) Fall from bicycle General lacerations Right side |

2 B2 | Conservative | Improvement of paresthesia after 2 months |

| 29 y; M | (LBT) Fall from motorcycle Fracture of left tibia Right side (JRS) |

2 B2 | Conservative | Improvement of paresthesia after 3 months |

| 24 y; M | Fall from motorcycle General lacerations Fracture of the right patella Left side (RMM) |

2 B2 | Conservative | Improvement of paresthesia after 3 months |

| 23 y; M | Fall from height Laceration of left shoulder Left side |

2 B1 | Conservative | Improvement of paresthesia after 2 months |

| 35 y; M | (MLS) Fall from standing position while playing soccer Left side |

2 B2 | Conservative | Improvement of paresthesia after 1 month |

None of the 32 patients who were treated surgically presented any complaints of paresthesia in the anterior region of the thorax.

Discussion

The frequency of displaced and comminuted diaphyseal fractures of the clavicle, resulting from high-energy trauma, has increased considerably.11

Supraclavicular nerve injuries in association with clavicle fractures are very rare. However, these nerves are situated in a vulnerable location, and operations on the posterior triangle of the cervical region may cause inadvertent damage to the nerve branches.12

The supraclavicular nerve emerges, in common with other cutaneous branches of the cervical plexus, at the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. It contains C3 and C4 fibers and divides into branches.12, 13, 14, 15 These are distributed into three main groups. The medial group innervates the region proximal to the sternal angle and the sternoclavicular joint.

The intermediate group passes anteriorly or occasionally through the clavicle and innervates the skin in the region of the anterior axial line. The lateral group passes close to the acromion, in the region of the deltoid muscle and also over the posterior region of the shoulder, and innervates the skin as far as the region of the scapular spine (posterior axial line).12

The proximity of the supraclavicular nerves to the clavicle makes them vulnerable to injury when the clavicle is fractured, or when surgical access to the clavicle is needed. The symptoms may comprise alterations to sensitivity located only in the dermatome of the nerve branch involved, or diffuse hyperesthesia resembling a regional painful syndrome.12, 16 Nathe et al.14 reported that 97%w of the specimens that they dissected contained medial and lateral branches of the supraclavicular nerve. Approximately half (49%) presented an additional intermediate branch. No branches were encountered closer than 2.7 cm from the sternoclavicular joint or 1.9 cm from the acromioclavicular joint. Between these two limits, there was great variation in the locations of the nerve branches. For this reason, diaphyseal fractures are more liable to cause nerve injury. Our evaluation demonstrated that the nerve injuries occurred in cases of diaphyseal fracture and that most of them were in cases of high-energy trauma with significant displacements (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Diagram showing the layout of the branches of the supraclavicular nerve. A, lateral branch; B, intermediate branch; C, medial branch.

Supraclavicular nerve injury can occur following traction. In some cases, the nerve branches were found passing through an osteofibrous tunnel. Gelberman et al.16 described resection of the nerve, while Omokawa et al.17 identified two patients in whom the tunnel was opened and the nerve branches were released.

Nerve injury has also been identified following closed fracturing of the clavicle. Ivey et al.18 successfully treated two patients with hypersensitivity in the anterior region of the thorax, by means of stellate ganglion block. Metha et al.12 described two patients in whom the area of the nerve injury was resected. In the present study, five patients presented hypoesthesia on the anterolateral face of the thorax following closed fracturing of the clavicle and achieved improvement of their symptoms over a period of approximately three months, without presenting signs of neuropathy.

With the growing numbers of indications for surgical treatment of clavicle fractures, surgeons should remain cautious in relation to the branches of the supraclavicular nerve, when constructing surgical accesses. Furthermore, attention should be paid to persistent pain associated with clavicle fractures that are treated conservatively or by means of internal fixation, because of the possibility of neuropathy of the supraclavicular nerve.10 It is worth emphasizing that, because of the great variation in the branches of the supraclavicular nerve, the symptoms may extend beyond the anatomical zone determined, and may include the proximal region of the deltoid and the posterolateral region of the scapular belt.16 The incidence of paresthesia subsequent to operations on clavicle fractures ranges from 12% to 29% in patients who were treated using a plate.19, 20 Wang et al.21 found paresthesia in 46% of their patients and observed that patients treatment with horizontal incisions were more liable to develop paresthesia than were those treated with vertical incisions. The group with horizontal incisions also presented a greater area of paresthesia. Although paresthesia is a tolerable complication, some patients do not tolerate this sensation and may cause problems for the surgeon. We suggest that vertical incisions should be used, so as to diminish the paresthesia and avoid patient dissatisfaction.

Conclusion

Clavicle fractures and/or surgery on the shoulder may injure the lateral, intermediate or medial branches of the supraclavicular nerve and cause alterations to sensitivity in the anterior region of the thorax. Knowledge of the anatomy of the nerve branches helps avoid problems in this region.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Work performed at the “Prof. Dr. Donato D’Ângelo” Orthopedics and Traumatology Service, Hospital Santa Teresa, Petrópolis, RJ, and the Petrópolis School of Medicine, Petrópolis, RJ, Brazil.

References

- 1.Rowe C.R. An atlas of anatomy and treatment of midclavicular fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1968;58:29–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nordqvist A., Petersson C. The incidence of fractures of the clavicle. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;(300):127–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Postacchini F., Gumina S., De Santis P., Albo F. Epidemiology of clavicle fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(5):452–456. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.126613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nowak J., Mallmin H., Larsson S. The aetiology and epidemiology of clavicular fractures. A prospective study during a two-year period in Uppsala, Sweden Injury. 2000;31(5):353–358. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(99)00312-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson C.M. Fractures of the clavicle in the adult. Epidemiology and classification. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(3):476–484. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.80b3.8079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allman F.L., Jr. Fractures and ligamentous injuries of the clavicle and its articulation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1967;49(4):774–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanley D., Trowbridge E.A., Norris S.H. The mechanism of clavicular fracture. A clinical and biomechanical analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70(3):461–464. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.70B3.3372571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan L.A., Bradnock T.J., Scott C., Robinson C.M. Fractures of the clavicle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(2):447–460. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Havet E., Duparc F., Tobenas-Dujardin A.C., Muller J.M., Fréger P. Morphometric study of the shoulder and subclavicular innervation by the intermediate and lateral branches of supraclavicular nerves. Surg Radiol Anat. 2007;29(8):605–610. doi: 10.1007/s00276-007-0258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Neill K., Stutz C., Duvernay M., Schoenecker J. Supraclavicular nerve entrapment and clavicular fracture. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(6):e63–e65. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31822c0796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeray K.J. Acute midshaft clavicular fracture. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(4):239–248. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200704000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehta A., Birch R. Supraclavicular nerve injury: the neglected nerve? Injury. 1997;28(7):491–492. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(97)00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romeo A.A., Rotenberg D.D., Bach B.R., Jr. Suprascapular neuropathy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999;7(6):358–367. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199911000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nathe T., Tseng S., Yoo B. The anatomy of the supraclavicular nerve during surgical approach to the clavicular shaft. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(3):890–894. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1608-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jelev L, Surchev L. Study of variant anatomical structures (bony canals, fibrous bands, and muscles) in relation to potential supraclavicular nerve entrapment. Clin Anat. 2007 Apr;20(3):278-85. PubMed PMID: 16838268. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Gelberman R.H., Verdeck W.N., Brodhead W.T. Supraclavicular nerve-entrapment syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57(1):119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Omokawa S., Tanaka Y., Miyauchi Y., Komei T., Takakura Y. Traction neuropathy of the supraclavicular nerve attributable to an osseous tunnel of the clavicle. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;(431):238–240. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000146742.21301.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ivey M., Britt M., Johnston R.V., Jr. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy after clavicle fracture: case report. J Trauma. 1991;31(2):276–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Canadian Orthopaedic Trauma Society. Nonoperative treatment compared with plate fixation of displaced midshaft clavicular fractures. A multicenter, randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(1):1-10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Shen W.J., Liu T.J., Shen Y.S. Plate fixation of fresh displaced midshaft clavicle fractures. Injury. 1999;30(7):497–500. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(99)00140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang K., Dowrick A., Choi J., Rahim R., Edwards E. Post- operative numbness and patient satisfaction following plate fixation of clavicular fractures. Injury. 2010;41(10):1002–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]