CONSPECTUS:

The catalytic construction of C–C bonds between organo-halide or -pseudohalide electrophiles and fundamental building blocks such as alkenes, arenes, or CO are widely utilized metal-catalyzed processes. The use of simple, widely available unactivated alkyl halides in these catalytic transformations has significantly lagged behind the use of aryl or vinyl electrophiles. This difference is primarily due to the relative difficulty in activating alkyl halides with transition metals under mild conditions. This account details our group’s work towards developing a general catalytic manifold for the construction of C–C bonds using unactivated alkyl halides and a range of simple chemical feedstocks. Critical to the strategy was the implementation of new modes of hybrid organometallic-radical reactivity in catalysis. Generation of carbon-centered radicals from alkyl halides using transition metals offers a solution to challenges associated with the application of alkyl electrophiles in classical two-electron reaction modes.

A major focus of this work was the development of general, palladium-catalyzed carbocyclizations and intermolecular cross-couplings of unactivated alkyl halides (alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-type reactions). Initial studies centered on the use of alkyl iodides in these processes, but subsequent studies determined that the use of an electron-rich, ferrocenyl bisphosphine (dtbpf) enables the palladium-catalyzed carbocyclizations of unactivated alkyl bromides. Mechanistic studies of these reactions revealed interesting details regarding a difference in mechanism between reactions of alkyl iodides and alkyl bromides in carbocyclizations. These studies were consistent with alkyl bromides reacting via an auto-tandem catalytic process involving atom-transfer radical cyclization (ATRC) followed by catalytic dehydrohalogenation. Reactions of alkyl iodides, on the other hand, involved metal-initiated radical chain pathways.

Recent studies have expanded the scope of alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-type reactions to the use of a first-row metal. Inexpensive nickel precatalysts, in combination with the bisphosphine ligand Xantphos, efficiently activate alkyl bromides for both intra- and intermolecular C–C bond-forming reactions. The reaction scope is similar to the palladium-catalyzed system, but in addition, alkene regioisomeric ratios are dramatically improved over those in reactions with palladium, solving one of the drawbacks of our previous work. Initial mechanistic studies were consistent with a hybrid organometallic-radical mechanism for the nickel-catalyzed reactions.

The novel reactivity of the palladium catalysts in the alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-type reactions have also paved the way for the development of other C–C bond-forming processes of unactivated alkyl halides, including aromatic C–H alkylations as well as low pressure alkoxycarbonylations. Related hybrid organometallic-radical reactivity of manganese has led to an alkene dicarbofunctionalization using alkyl iodides.

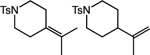

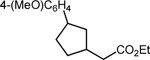

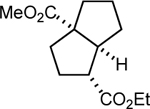

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The catalytic construction of C–C bonds is invaluable to the synthesis and discovery of industrially- and medicinally-relevant compounds. Classical transition-metal-catalyzed cross-couplings such as the Suzuki-Miyaura, Negishi, and Mizoroki-Heck reactions are indispensable methodologies of this class.1 Despite the synthetic utility of these processes, applications have traditionally been limited to the use of activated, or sp2-hybridized aryl or vinyl electrophiles. Modern studies in transition metal catalysis have extended organometallic cross-couplings to reactions with unactivated alkyl electrophiles.2–4 However, at the outset of our studies, there were few general examples of catalytic C–C bond-forming reactions of unactivated alkyl halides with non-organometallic building blocks such as alkenes, arenes, or CO.

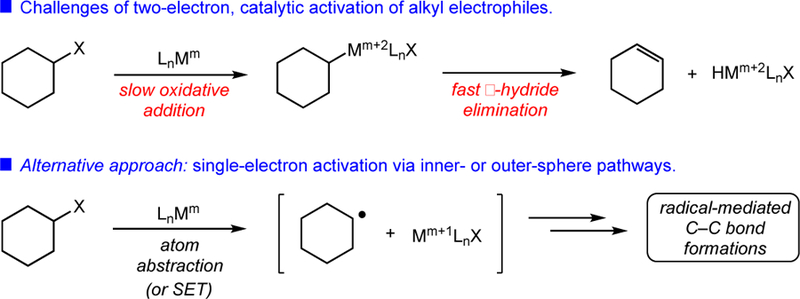

Alkyl halides are ubiquitous chemical building blocks which are widely commercially available and easily synthesized from simple and abundant starting materials. The use of unactivated alkyl halides in transition-metal-catalyzed C–C bond-forming reactions has posed a significant synthetic challenge, however, owing to (1) the relative reluctance of electron-rich, sp3-hybridized electrophiles to undergo oxidative addition with low-valent metal complexes5,6 and (2) the susceptibility of alkylmetal intermediates toward rapid β-hydride elimination rather than desired C–C bond formation (Figure 1).7,8

Figure 1.

Two- and single-electron activation of unactivated alkyl electrophiles.

These limitations of two-electron activation mechanisms must be overcome for successful C–C construction. In cases involving organometallic cross-coupling, this has been accomplished via the judicious selection of ligands.9,10 However, with rare exceptions,11 this approach has not translated to other C–C constructions involving non-organometallic coupling partners (e.g., alkenes). We viewed an alternative activation method as holding potential in mitigating these problems. Many transition metal complexes are known to participate in single-electron activation modes with alkyl electrophiles through either an inner-sphere atom abstraction or outer-sphere single-electron transfer pathway to yield a carbon-centered radical intermediate (Figure 1).12 The carbon-centered radical thus formed is capable of participating in any of a number of C–C bond-forming reactions. This type of single-electron manifold offers a solution to the slow oxidative addition associated with two-electron reactivity, while minimizing the formation of putative alkylmetal intermediates which could lead to deleterious, premature β-hydride elimination.

The use of hybrid organometallic-radical pathways in alkene additions had significant precedent at the start of our studies, most notably in atom-transfer radical additions.13,14 Applications involving unactivated alkyl electrophiles were rare, however, and required the use of superstoichiometric amounts of reactive alkylmetal reagents.15–17 In this account, we detail our work focused on developing general alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-type reactions under mild conditions and the revealing mechanistic studies involved. These studies subsequently led to our group developing several other C–C constructions in the hybrid organometallic-radical manifold, which will also be discussed.

PALLADIUM-CATALYZED CARBOCYCLIZATIONS OF UNACTIVATED ALKYL IODIDES

We began our studies with the goal of developing a carbonylative Mizoroki-Heck-type reaction of unactivated alkyl iodides.18 Our decision to use alkyl iodides as substrates was guided by the higher inherent reactivity of alkyl iodides over other alkyl halides in single-electron manifolds.19 We hypothesized that the CO involved in the reaction would limit undesired dehydrohalogenation owing to either the known addition of carbon-centered radicals to CO–avoiding the production of an alkylpalladium(II) intermediate–or to fast CO migratory insertion if such an intermediate did indeed form.20 Important precedent for this work was Ryu’s application of a palladium/light system for a cascade radical cyclization in a multi-carbonylation sequence.21 This prior work demonstrated the ability of a palladium catalyst to successfully form five-membered cyclic ketones via radical cyclization.

Representative examples of successful carbonylative ring formations are shown in Table 1. These reactions were successfully catalyzed using simple Pd(PPh3)4, albeit under relatively high pressure (50 atm) and temperature (130 °C). A variety of cyclic enones were prepared from both primary and secondary alkyl iodides. Both monocyclic and bicyclic structures were easily accessible via 5-exo and 6-endo modes of cyclization.

Table 1.

Representative Palladium-Catalyzed Carbonylative Carbocyclizations.a

| entry | substrate | product | yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

|

77 10:1 E:Z |

| 2 |  |

|

55 >25:1 E:Z |

| 3 |  |

|

63 1.3:1 rr |

| 4 |  |

|

74 7.1:1 rr |

| 5 |  |

|

91 1.2:1 dr |

| 6 |  |

|

69 |

| 7 |  |

|

90 |

Reactions performed with [substrate]0 = 0.5 M in PhMe at 130 °C under 50 atm CO with 10 mol % Pd(PPh3)4 and 2 equiv iPr2EtN.

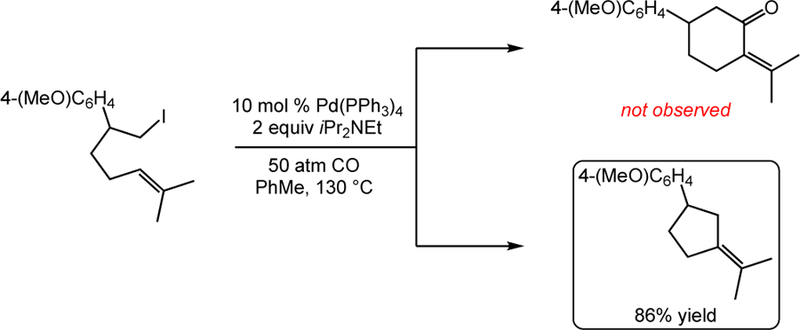

While studying the substrate scope of this carbocyclization, we obtained an exciting and unexpected result which led our investigations down a new avenue.22 The reaction of a hexenyl iodide was anticipated to produce a six-membered enone via a carbonylative 6-exo cyclization (Scheme 1). This product was not observed, however, and instead the sole product was that of a non-carbonylative 5-exo cyclization to give a methylene cyclopentane product in 86% yield as a single alkene regioisomer. We were intrigued by the potential for this process, as such a palladium-catalyzed carbocyclization of unactivated alkyl halides was unknown with the exception of a single report limited to five-membered ring synthesis involving terminal alkenes.11

Scheme 1.

Non-Carbonylative Pathway Favored in Attempted 6-Exo Carbonylative Carbocyclization.

As CO is not incorporated in the reaction, the next experiment was to perform the carbocyclization in its absence. Unexpectedly, while this modification in reaction conditions did not influence reaction efficiency to a large extent, the production of another alkene regioisomer was observed (Scheme 2). While we were able to decrease the CO pressure from 50 atm to 10 atm, lowering pressure further to 2 atm CO led to a significant amount of this undesired regioisomer. This effect was observed with other primary alkyl iodides as well, and in addition these conditions led to a decrease in the production of reductive byproducts. Therefore, these carbocyclizations were performed under 10 atm CO. Interestingly, our studies of substrate scope revealed that reactions of secondary alkyl iodides did not benefit from a CO atmosphere and proceeded efficiently when performed under argon (see below).

Scheme 2.

Unexpected Effect of Carbon Monoxide on the Efficiency of the Non-Carbonylative Carbocyclization.

The carbocyclization succeeded with a range of primary and secondary alkyl iodides containing diverse alkene substitution patterns, enabling the synthesis of 5- and 6-membered carbo- and heterocycles (Table 2). The reaction also efficiently constructed products containing all-carbon quaternary centers. Several bicyclic structures were prepared in good yield, although a mixture of alkene regioisomers formed in certain instances. Notably, the carbocyclization was not limited to the formation of 5-membered rings, as 6-exo cyclization was also possible. As previously mentioned, carbocyclizations of secondary alkyl iodides did not benefit from a CO atmosphere; reactions of this substrate class were performed under Ar with good efficiency. We speculate that the carbocyclizations of primary iodides performed in this study benefited from the CO atmosphere owing to modification of the reactivity profile of the palladium catalyst, although detailed mechanistic studies have not been performed. This issue is resolved in later generations of the reaction, which avoid CO altogether (vide infra).23,24

Table 2.

Representative Palladium-Catalyzed Carbocyclizations of Unactivated Alkyl Iodides.a

Reactions performed with [substrate]0 = 0.5 M in PhH at 110 °C under 10 atm CO with 10 mol % Pd(PPh3)4 and 2 equiv PMP (1,2,2,6,6-pentamethylpiperidine).

Reaction temperature 130 oC.

Reaction performed under Ar.

With respect to the reaction mechanism, our early studies sought to determine whether the carbocyclizations proceeded via single- or two-electron mechanisms. Prior studies have demonstrated that both pathways potentially proceed in reactions of low-valent palladium and alkyl iodides.25,26 Carbonylative and non-carbonylative cyclizations were performed in the presence of 1 equiv of the persistent radical TEMPO ((2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxyl), and in both cases, the TEMPO-trapped adducts were observed (Scheme 3). These results are consistent with the intermediacy of carbon-centered radicals in these reactions involving single-electron mechanisms. Subsequent studies shed light on other mechanistic details of the reactions (vide infra).24

Scheme 3.

Initial Mechanistic Studies Involving Persistent Radical TEMPO.

INTERMOLECULAR PALLADIUM-CATALYZED MIZOROKI-HECK-TYPE CROSS-COUPLINGS OF UNACTIVATED ALKYL IODIDES

Following our carbocyclization studies, we targeted a complementary method involving the intermolecular cross-couplings of unactivated alkyl iodides.27 At the time of our studies, general methods for intermolecular alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-type reactions required the use of reactive reductants (i.e. stoichiometric alkylmetal reagents) and were limited to cross-couplings involving styrene.15,16,28–30 Using palladium catalysis, we were able to overcome these limitations and develop an alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-type cross-coupling using non-styrenyl substrates. We began our studies with the catalytic cross-coupling of iodocyclohexane with acrylonitrile (Scheme 4). Initially, a significant amount of a reductive addition product was observed along with the desired cross-coupling product. We determined that switching to a solvent lacking abstractable hydrogen atoms (PhCF3) and the use of an inorganic base instead of an amine base (K3PO4 instead of Cy2NMe) minimized this byproduct. Further studies indicated that the optimal base was dependent on the identity of the alkene coupling partner; Cy2NMe proved to be superior in reactions with styrenes.

Scheme 4.

Palladium-Catalyzed Alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-Type Cross-Coupling.

With respect to substrate scope, a number of non-styrenyl alkenes were amenable to the cross-coupling–a distinct advantage over existing intermolecular alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-type processes (Scheme 5). Moreover, both primary and secondary alkyl iodides performed well in the reaction. In addition, the reaction of a substrate containing a β-stereogenic center proceeded without epimerization, indicating that reversible β-hydride elimination does not occur prior to coupling.

Scheme 5.

Representative Examples of Palladium-Catalyzed, Intermolecular Alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-Type Cross-Couplings.

Mechanistic studies supported a hybrid organometallic-radical pathway similar to the catalytic carbocyclizations. For example, the reaction of acrylonitrile with a diastereomerically pure, cyclohexyl substrate produced a cross-coupling product in 50:50 dr. Furthermore, the reaction of styrene with a radical-clock (6-iodohex-1-ene) led to exclusive formation of the cyclopentyl product with no linear cross-coupling product observed, consistent with the presence of a carbon-centered radical intermediate which undergoes fast 5-exo cyclization (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

Mechanistic Probes for Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Couplings.

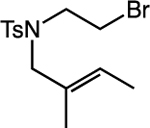

PALLADIUM-CATALYZED MIZOROKI-HECK-TYPE CARBOCYCLIZATIONS OF UNACTIVATED ALKYL BROMIDES

Following our initial studies, we sought to develop new protocols for the alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-type carbocyclizations which addressed important drawbacks that limited the practicality of our approach.24 Firstly, the use of heat- and light-sensitive alkyl iodides in these reactions was less attractive than more stable unactivated alkyl bromides. Applying our previously-developed system to the transformation of alkyl bromides gave little product, however; such substrates are inherently more difficult to activate using metal catalysis.31 Furthermore, as mentioned previously, carbocyclizations of primary alkyl halides required the use of CO atmosphere which was suboptimal. A survey of electron-rich, bidentate ferrocenyl ligands led to a catalytic system which addressed both of these issues (Scheme 7). As with our intermolecular coupling, the use of PhCF3 instead of PhMe was important to limit the formation of reductive byproducts.

Scheme 7.

Palladium-Catalyzed Carbocyclization of Unactivated Alkyl Bromides.

Our studies applying this second-generation catalytic system to reactions of alkyl bromides demonstrated increased reaction efficiencies over our previous carbocyclizations of alkyl iodides in nearly all cases (Table 3, entries 1–5). Importantly, these carbocyclizations avoided the use of a CO atmosphere. This catalytic system also expanded the scope of the carbocyclization to include substrates that were not well-tolerated in our reactions of alkyl iodides. For example, substrates with styrenyl and terminal olefins worked well, and we successfully expanded capabilities in accessing 6-membered heterocycles (Table 3, entries 8–9).

Table 3.

Alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-Type Carbocyclizations of Unactivated Alkyl Bromides.a

| entry | substrate | product | yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

|

90 |

| 2 |  |

|

80 |

| 3 |  |

|

77 7.2:3:1 rr |

| 4 |  |

|

82 4.3:1 rr |

| 5 |  |

|

93 >95:5 dr |

| 6 |  |

|

65 1:1 E:Z |

| 7b |  |

|

65 |

| 8c |  |

|

92 1.9:1 rr |

| 9 |  |

|

75 >95:5 dr 1.5:1 E:Z |

Reactions performed with [substrate]0 = 0.25 M in PhCF3 at 100 °C with 5 mol % [Pd(allyl)Cl]2, 20 mol % dtbpf, and 2 equiv Et3N as base.

DBU used as base instead of Et3N.

Reaction performed at 120 °C with 5 mol % [Pd(allyl)Cl]2, 20 mol % dtbpf, and 2 equiv Cy2NMe as base.

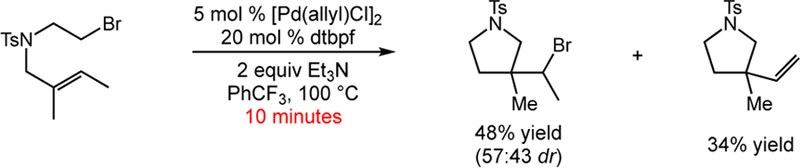

Following our synthetic studies, we sought to gain a detailed understanding of the reaction mechanism. We began by determining if any reaction intermediates could be found at partial conversion. Surprisingly, after 10 minutes we observed an atom-transfer radical cyclization (ATRC) product in addition to the expected alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-type product (Scheme 8). We were able to select for these bromine ATRC products by slight modification of the reaction conditions. Existing methods for the ATRC of alkyl bromides require highly activated substrates.32 While Mitani and co-workers have demonstrated intermolecular atom-transfer radical addition (ATRA) reactions of unactivated alkyl halides,33 our studies disclosed the first examples of ATRC involving unactivated alkyl bromides. With respect to mechanism, it became clear that direct production of the desired carbocyclization product was not the sole reaction pathway.

Scheme 8.

Palladium-Catalyzed Carbocyclization at Short Reaction Time.

Our next major focus was on identifying the role of palladium in the radical cyclization step–specifically, whether palladium served as a simple radical chain initiator or as a true catalyst, and whether reactions of alkyl bromides and iodides proceeded via the same mechanism. We began by comparing the carbocyclizations of an alkyl bromide substrate and its corresponding iodide in the absence and presence of the single-electron inhibitor 1,4-dinitrobenzene (Table 4). Under standard reaction conditions, the reactions of the alkyl bromide and alkyl iodide proceeded in 77% and 48% yield, respectively. The reaction of the alkyl bromide in the presence of 10 mol % 1,4-dinitrobenzene resulted in low yield and conversion, however. Surprisingly, reaction of the corresponding iodide in the presence of 10 mol % 1,4-dinitrobenzene still gave the expected product in high yield.

Table 4.

Carbocyclizations of an Alkyl Bromide and Corresponding Iodide in the Presence of a Single-Electron Inhibitor.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | conditions | conversion (%)a | yield (%)a |

| 1 | X = Br, no additive | 100 | 77 |

| 2 | X = I, no additive | 100 | 48 |

| 3 | X = Br, with 10 mol % dinitrobenzene | <2 | <2 |

| 4 | X = I, with 10 mol % dinitrobenzene | 100 | 78 |

Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as internal standard.

We next studied the dehydrohalogenation of the ATRC intermediates observed in these reactions. In preparation for these studies, we determined that the ATRC of alkyl iodides are also fast; the reaction of the alkyl iodide in Table 4 provided the ATRC product in 68% yield after only 1 minute. Resubjection of the alkyl bromide or iodide ATRC products to the standard reaction conditions provided the expected alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-type products (Table 5). We next studied the dehydrohalogenations in the presence of 1,4-dinitrobenzene. The reaction of the alkyl bromide was significantly inhibited, while the reaction of the alkyl iodide was unaffected. Furthermore, in the absence of metal or ligand, no dehydrohalogenation of the alkyl bromide was observed, while in the case of the alkyl iodide, a significant amount of base-mediated elimination occurred.

Table 5.

Dehydrohalogenation Studies of Alkyl Bromide and Iodide ATRC Intermediates.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | conditions | conversion (%)a | yield (%)a |

| 1 | X = Br, no additive | 100 | 100 |

| 2 | X = I, no additive | 100 | 97 |

| 3 | X = Br, with 10 mol % dinitrobenzene | 22 | 9 |

| 4 | X = I, with 10 mol % dinitrobenzene | 100 | 100 |

| 5 | X = Br, no metal or ligand | <2 | <2 |

| 6 | X = I, no metal or ligand | 56 | 37 |

Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as internal standard.

The results of these studies are consistent with an auto-tandem catalytic mechanism34,35 for the carbocyclizations of unactivated alkyl bromides (Scheme 9). Single-electron activation of the alkyl bromide substrate provides a carbon-centered radical intermediate which undergoes addition to the pendant alkene. Following cyclization, bromine atom transfer delivers the ATRC alkyl bromide. Subsequent single-electron activation of this product followed by addition to palladium and β-hydride elimination gives the carbocyclization product and regenerates the catalyst.

Scheme 9.

Proposed Mechanism for the Carbocyclization of Alkyl Bromides Involving Auto-Tandem Catalysis.

Interestingly, we hypothesize that reactions involving unactivated alkyl iodides proceed via a different mechanism, namely through a metal-initiated, rather than metal-catalyzed, radical chain process (Scheme 10). As further support of this hypothesis, we examined the reactions of representative alkyl bromide and iodide substrates with a more traditional radical initiator, AIBN, in the absence of a metal catalyst. Alkyl iodides are well known to participate in ATRC reactions via innate chain processes,36 and our studies above indicated that simple base-mediated deiodination was possible (Table 5). While the reaction of the bromide depicted in Scheme 7 proceeded with low conversion in the presence of AIBN, the reaction of the corresponding iodide furnished the carbocyclization product in moderate yield, indicating that the palladium is simply serving as a radical initiator in the reactions of alkyl iodides.

Scheme 10.

Proposed Mechanism for the Carbocyclization of Alkyl Iodides Involving an Innate Chain Reaction.

NICKEL-CATALYZED ALKYL-MIZOROKI-HECK-TYPE REACTIONS OF UNACTIVATED ALKYL BROMIDES

Extending the palladium-catalyzed carbocyclizations to unactivated alkyl bromides significantly increased the scope of our approach, yet upon critical examination, we identified two major limitations that remained. The transformations often proceeded with modest alkene regioselectivity, and the requirement of a precious metal precatalyst was also suboptimal. Given the versatility of inexpensive nickel catalysts in the activation of alkyl halides for a variety of cross-couplings and other synthetically useful transformations,37–39 we hypothesized that a nickel-catalyzed method for alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-type carbocyclizations could be developed. A potential challenge we envisioned was the documented higher energy barrier for β-hydride elimination of alkylnickel(II) species versus their palladium counterparts.40 At the start of our studies, existing methods for such nickel-catalyzed carbocyclizations were limited to the use of activated substrates, or alkyl iodides in reactions that produced both alkene regioisomers and reductive cyclization byproducts.29,41,44 We sought a nickel catalytic system that used unactivated alkyl bromides as substrate and minimized the production of alkene regioisomers to enhance the utility of this manifold.23

Initial attempts towards a nickel-catalyzed alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-type reaction of alkyl bromides using bipyridine-type ligands typical of related nickel-catalyzed transformations produced large amounts of the reductive cyclization byproduct in addition to the desired product. An extensive ligand screen uncovered that by switching to the bisphosphine ligand 4,5-bis(diphenylphosphino)-9,9-dimethylxanthene (Xantphos), we were able to both minimize the formation of any reductive cyclization byproducts and facilitate the alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-type process in excellent yields and alkene regioisomeric ratios (Scheme 11). Furthermore, the use of an air-stable nickel precatalyst (NiBr2·glyme) allowed for reaction setup without a glovebox, another distinct advantage over the palladium-catalyzed reactions described above.

Scheme 11.

Nickel-Catalyzed Alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-Type Reaction of Unactivated Alkyl Bromides.

We applied our catalytic system to the carbocyclizations of a range of substrates (Table 6). While yields were generally comparable to those in our palladium-catalyzed work, alkene regioisomeric ratios were significantly improved. Carbocyclizations involving di- and trisubstituted pendant alkenes, styrenes, or terminal alkenes all proceeded in good yield and with excellent alkene regioselectivity. Applications to the synthesis of bicyclic frameworks and six-membered rings was also possible. The new catalytic system also extended the scope to products that were previously inaccessible using our Pd/dtbpf conditions, such as the spirocyclic compound formed in entry 6.

Table 6.

Substrate Scope for Nickel-Catalyzed Alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-Type Carbocyclizations.a

| entry | substrate | product | yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

|

86 1.1:1 E:Z |

| 2 |  |

|

84 >25:1 rr |

| 3 |  |

|

82 15:1 rr |

| 4 |  |

|

86 1.6:1 E:Z |

| 5 |  |

|

70 >25:1 rr |

| 6b |  |

|

80 3.1:1 rr |

| 7 |  |

|

64 >25:1 rr |

Reactions performed with [substrate]0 = 0.25 M in MeCN at 80 °C with 10 mol % NiBr2·glyme, 10 mol % Xantphos, 3 equiv Mn, and 3 equiv Et3N as base.

Reaction performed with [substrate]0 = 0.25 M in DMSO.

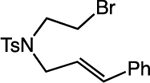

In concert with our cyclization studies, we also explored the possibility for nickel-catalyzed intermolecular alkenylations. Our studies indicated that acyclic or cyclic secondary alkyl bromides were viable substrates in cross-couplings with acrylonitrile or methyl acrylate (Table 7). On the other hand, primary alkyl bromides were poor substrates, and cross-couplings with styrene were also unsuccessful, as styrene dimers predominated.

Table 7.

Substrate Scope for Cross-Couplings of Alkyl Bromides.a

Reactions performed with [substrate]0 = 0.5 M in DMF at 70 °C with 10 mol % Ni(COD)2, 10 mol % Xantphos, 3 equiv alkene, 3 equiv Mn, and 3 equiv Et3N as base.

Reaction performed with [substrate]0 = 0.5 M in MeCN.

Na2CO3 used as base instead of Et3N.

Yield determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy of crude reaction mixture using an internal standard.

We performed several experiments to further understand the mechanism of the nickel-catalyzed reactions (Scheme 12). Under standard conditions, the addition of 10 mol % of the single-electron inhibitor 1,4-dinitrobenzene led to complete recovery of unreacted starting material, consistent with the presence of radical intermediates. In contrast to the palladium-catalyzed transformation, no ATRC product was observed at partial conversion, consistent with a direct alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-type carbocyclization not involving auto-tandem catalysis. We hypothesize that the excellent regioisomeric ratios observed in the reaction are a result of alkene isomerization occurring over the course of the reaction, as low selectivity was observed at short reaction times (see Scheme 11 for the minor regioisomer).

Scheme 12.

Mechanistic Studies of the Nickel-Catalyzed Alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-Type Reaction.

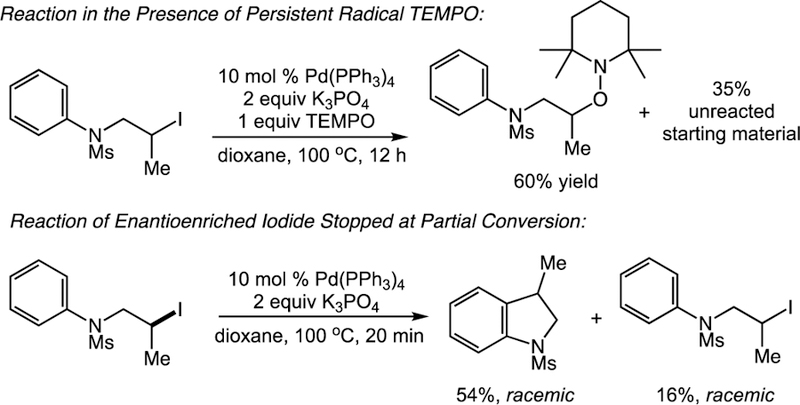

PALLADIUM-CATALYZED AROMATIC C–H ALKYLATIONS WITH UNACTIVATED ALKYL HALIDES

Building upon our successes in the development of alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-type processes, we sought to capitalize on the catalytic hybrid organometallic-radical reactivity to enable C–C bond constructions involving unsaturated units other than alkenes. We viewed aromatic C–H alkylation as a particularly interesting goal, owing to the limitations in substrate scope of canonical Friedel-Crafts alkylations43 and radical-mediated homolytic aromatic substitutions.44 The use of simple Pd(PPh3)4 as catalyst–similar to our early alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck studies–led to a general palladium-catalyzed, ring-forming aromatic C–H alkylation using unactivated alkyl halides.45 Primary and secondary alkyl iodides and bromides were competent substrates for the construction of a diverse array of polycyclic carbocycles and heterocycles (Table 8).

Table 8.

Representative Examples of Palladium-Catalyzed, Ring-Forming C–H Alkylations.a

| entry | substrate | product | yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| 1 | X = Br | 91 | |

| 2 | X = I | 85 | |

|

|

||

| 3b | X = Br | 89 | |

| 4 | X = I | 51 | |

|

|

||

| 5b | X = Br | 54 | |

| 6 | X = I | 82 | |

|

|

||

| 7 | R = H | R = H | 70c |

| 8 | R = Me | R = Me | 90c |

All reactions were performed with [substrate]0 = 0.5 M and 10 mol % Pd(PPh3)4 as catalyst. The reactions of alkyl bromides were performed in PhtBu at 130 °C with 2 equiv PMP (1,2,2,6,6-pentamethylpiperidine) as base. The reactions of alkyl iodides were performed in dioxane at 100 °C with 2 equiv K3PO4 as base.

K3PO4 used as base.

Yield determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy of crude reaction mixture using an internal standard.

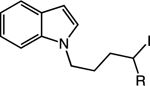

As with the alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck-type reactions, mechanistic studies of the C–H alkylation were consistent with a single-electron activation pathway. Once again, a reaction conducted under standard conditions in the presence of persistent radical TEMPO provided the TEMPO-trapped adduct while no C–H alkylation was observed. Furthermore, reaction of an enantioenriched iodide substrate stopped at partial conversion yielded racemic product. Interestingly, the recovered starting material was completely racemic as well, supporting a reversible single-electron activation of the alkyl halide prior to cyclization (Scheme 13).

Scheme 13.

Mechanistic Studies of the Palladium-Catalyzed C–H Alkylation.

A mechanistic proposal consistent with our studies is depicted in Scheme 14. Following reversible, single-electron activation of the alkyl halide substrate, we propose that a carbon-centered radical then adds to the aromatic ring to form a cyclohexadienyl radical intermediate. Single-electron transfer with a putative palladium(I) intermediate and subsequent deprotonation with base produces the final product. An alternative mechanistic pathway is possible in which addition of the cyclohexadienyl radical to palladium(I) followed by β-hydride elimination of the resulting alkylmetal species gives the product.

Scheme 14.

Proposed Mechanism of the Palladium-Catalyzed C–H Alkylation.

MANGANESE-CATALYZED CARBOACYLATIONS OF ALKENES WITH ALKYL IODIDES

We also sought to extend the hybrid organometallic-radical reactivity to alkene dicarbofunctionalizations. In contrast to the many examples of alkene difunctionalizations involving the addition of two heteroatoms, alkene dicarbofunctionalizations, involving the formation of two C–C bonds, were rare when we began our studies in this area.46 We hypothesized that following the cyclization of the carbon-centered radical as in the alkyl-Mizoroki-Heck work, carbonylation instead of β-hydride elimination would lead to a ring-forming carboacylation process. Early studies indicated that palladium catalysis would not prove suitable for the development of such a transformation, and we became interested in the attractive possibility of using cheaper and more earth-abundant first row transition metals in these reactions. Manganese catalysts are known to participate in both single-electron activation and carbonylation of unactivated alkyl halides and thus appeared suitable for this purpose.47–49 Indeed, simple and commercially available Mn2CO10 efficiently catalyzed a ring-forming carboacylation of alkenes with alkyl iodides under mild conditions and low CO pressures for the synthesis of a variety of carbocyclic and heterocyclic products (Table 9).50

Table 9.

Representative Manganese-Catalyzed Carboacylations.a

| entry | substrate | product | yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

|

83 2:1 dr |

| 2 |  |

|

R = OEt 77, 10:1 dr R = NMePhb 73, 10:1 dr |

| 3c |  |

|

79 1:1 dr |

| 4c |  |

|

64 |

| 5c |  |

|

78 3:1 dr |

| 6 |  |

|

89 7:1 dr |

All reactions were performed with [substrate]0 = 0.13 M in EtOH with 2.5 mol % Mn2(CO)10, 1 equiv KHCO3, and 10 atm CO at rt.

2 equiv amine and KHCO3 used.

5 mol % Mn2(CO)10 used.

Primary and secondary alkyl iodides underwent successful reactions to form a variety of carbo- and heterocycles via 5-exo, 6-exo, and 7-endo cyclization processes. Both alcohols and amines could be used to intercept putative acylmanganese intermediates in the termination step, delivering ester and amide products in high yield.

PALLADIUM-CATALYZED ALKOXYCARBONYLATIONS OF UNACTIVATED ALKYL BROMIDES

The hybrid organometallic-radical activation mode of palladium catalysis used to generate radical intermediates from alkyl halides has utility in other valuable C–C bond-forming reactions beyond alkene (or arene) addition processes. Carbonylations of aryl and vinyl electrophiles have found widespread use in a range of synthetic contexts.51 Applications to unactivated alkyl electrophiles are much less precedented, typically requiring high CO pressures, specialized light irradiation, or the use of relatively unstable alkyl iodides as substrates.52 We hypothesized that the application of the modes of catalysis described herein would enable a mild, low pressure palladium-catalyzed alkoxycarbonylation of alkyl bromides, constituting the first examples of catalytic carbonylations of unactivated alkyl bromides. Upon identification of a suitable catalytic system featuring 5 mol % Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 as precatalyst and 10 mol % IMes as ligand, a general alkoxycarbonylation was developed.53 A diverse range of aliphatic, heterocyclic, and complex substrates were efficiently transformed using a variety of alcohols as nucleophiles (Scheme 15).

Scheme 15.

Palladium-Catalyzed Alkoxycarbonylations of Unactivated Alkyl Bromides.

Mechanistic studies of the alkoxycarbonylation are consistent with an activation step involving an irreversible bromine atom abstraction to generate a carbon-centered radical intermediate. The C–C bond-forming step may involve either outer-sphere addition to a carbonyl ligand, or recombination with the palladium center and migratory insertion to provide an acyl palladium intermediate. Subsequent nucleophilic attack of alkoxide on the acylpalladium intermediate furnishes the product (Scheme 16).

Scheme 16.

Proposed Mechanism for the Catalytic Alkoxycarbonylation.

CONCLUSIONS

In recent years, creative applications of hybrid organometallic-radical catalysis by many research groups has led to unique transformations for organic synthesis. Our studies in this area have featured new modes of reactivity in this class using palladium, nickel, and manganese catalysis to develop several valuable C–C bond-forming reactions of unactivated alkyl halides. The transformations developed used widely available and synthetically accessible alkyl iodides and bromides in reactions with ubiquitous chemical building blocks such as alkenes, arenes, and carbon monoxide. Current work continues to develop new reaction platforms for C–C bond construction using unactivated alkyl electrophiles and first-row transition metal catalysts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by Award No. R01 GM107204 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION

Megan R. Kwiatkowski completed her B.S. in biochemistry in 2015 at the University of Michigan where she conducted undergraduate research with Professor Masato Koreeda. In 2015, she moved to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and began her graduate studies with Professor Erik Alexanian. Her research has focused on the development of metal-catalyzed reactions using unactivated alkyl electrophiles.

Erik J. Alexanian was born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1979. He earned his A.B. in chemistry in 2001 from Harvard University where he worked in the laboratory of Prof. Amir Hoveyda at Boston College. He obtained his Ph.D. from Princeton University under the direction of Professor Erik Sorensen, and carried out postdoctoral studies with Professor John Hartwig at Yale University and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. In 2008, he joined the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and was promoted to associate professor in 2014. Research in the Alexanian laboratory focuses on the development of novel transformations using fundamental synthetic building blocks.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Johansson Seechurn CCC; Kitching MO; Colacot TJ; Snieckus V Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling: A Historical Contextual Perspective to the 2010 Nobel Prize. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 5062–5085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Luh T-Y; Leung M; Wong K-T Transition Metal-Catalyzed Activation of Aliphatic C−X Bonds in Carbon−Carbon Bond Formation. Chem. Rev 2000, 100, 3187–3204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Kambe N; Iwasaki T; Terao J Pd-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions of Alkyl Halides. Chem. Soc. Rev 2011, 40, 4937–4947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Frisch AC; Beller M Catalysts for Cross-Coupling Reactions with Non-Activated Alkyl Halides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2005, 44, 674–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Collman JP Disodium Tetracarbonylferrate, a Transition Metal Analog of a Grignard Reagent. Acc. Chem. Res 1975, 8, 342–347. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Pearson RG; Figdore PE Relative Reactivities of Methyl Iodide and Methyl Tosylate with Transition-Metal Nucleophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1980, 102, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Ozawa F; Ito T; Yamamoto A Mechanism of Thermal Decomposition of Trans-Diethylbis(Tertiary Phosphine)Palladium(II). Steric Effects of Tertiary Phosphine Ligands on the Stability of Diethylpalladium Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1980, 102, 6457–6463. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hartwig J Organotransition Metal Chemistry: From Bonding to Catalysis; University Science Books: Sausalito, CA, 2009; Chapter 10, pp 398–402. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Lee J-Y; Fu GC Room-Temperature Hiyama Cross-Couplings of Arylsilanes with Alkyl Bromides and Iodides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 5616–5617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Netherton MR; Dai C; Neuschütz K; Fu GC Room-Temperature Alkyl−Alkyl Suzuki Cross-Coupling of Alkyl Bromides That Possess β Hydrogens. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123, 10099–10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Firmansjah L; Fu GC Intramolecular Heck Reactions of Unactivated Alkyl Halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 11340–11341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Jahn U Radicals in Transition Metal Catalyzed Reactions? Transition Metal Catalyzed Radical Reactions?: A Fruitful Interplay Anyway. In Radicals in Synthesis III; Heinrich M, Gansäuer A, Eds.; Topics in Current Chemistry; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012; pp 323–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Severin K Ruthenium Catalysts for the Kharasch Reaction. Curr. Org. Chem 2006, 10, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Matyjaszewski K From Atom Transfer Radical Addition to Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. Curr. Org. Chem 2002, 6, 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Affo W; Ohmiya H; Fujioka T; Ikeda Y; Nakamura T; Yorimitsu H; Oshima K; Imamura Y; Mizuta T; Miyoshi K Cobalt-Catalyzed Trimethylsilylmethylmagnesium-Promoted Radical Alkenylation of Alkyl Halides: A Complement to the Heck Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 8068–8077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Ikeda Y; Nakamura T; Yorimitsu H; Oshima K Cobalt-Catalyzed Heck-Type Reaction of Alkyl Halides with Styrenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 6514–6515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Terao J; Watabe H; Miyamoto M; Kambe N Titanocene-Catalyzed Alkylation of Aryl-Substituted Alkenes with Alkyl Halides. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 2003, 76, 2209–2214. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Bloome KS; Alexanian EJ Palladium-Catalyzed Carbonylative Heck-Type Reactions of Alkyl Iodides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 12823–12825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Newcomb M; Sanchez RM; Kaplan J Fast Halogen Abstractions from Alkyl Halides by Alkyl Radicals. Quantitation of the Processes Occurring in and a Caveat for Studies Employing Alkyl Halide Mechanistic Probes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1987, 109, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Sumino S; Fusano A; Fukuyama T; Ryu I Carbonylation of Alkyl Iodides through the Interplay of Carbon Radicals and Pd Catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res 2014, 47, 1563–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Ryu I; Kreimerman S; Araki F; Nishitani S; Oderaotoshi Y; Minakata S; Komatsu M Cascade Radical Reactions Catalyzed by a Pd/Light System: Cyclizative Multiple Carbonylation of 4-Alkenyl Iodides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 3812–3813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Bloome KS; McMahen RL; Alexanian EJ Palladium-Catalyzed Heck-Type Reactions of Alkyl Iodides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 20146–20148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Kwiatkowski MR; Alexanian EJ Nickel-Catalyzed Mizoroki–Heck-Type Reactions of Unactivated Alkyl Bromides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 16857–16860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Venning ARO; Kwiatkowski MR; Roque Peña JE; Lainhart BC; Guruparan AA; Alexanian EJ Palladium-Catalyzed Carbocyclizations of Unactivated Alkyl Bromides with Alkenes Involving Auto-Tandem Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 11595–11600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Kirchhoff JH; Netherton MR; Hills ID; Fu GC Boronic Acids: New Coupling Partners in Room-Temperature Suzuki Reactions of Alkyl Bromides. Crystallographic Characterization of an Oxidative-Addition Adduct Generated under Remarkably Mild Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 13662–13663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Stadtmüller H; Vaupel A; Tucker CE; Stüdemann T; Knochel P Stereoselective Preparation of Polyfunctional Cyclopentane Derivatives by Radical Nickel- or Palladium-Catalyzed Carbozincations. Chem.–Eur. J 1996, 2, 1204–1220. [Google Scholar]

- (27).McMahon CM; Alexanian EJ Palladium-Catalyzed Heck-Type Cross-Couplings of Unactivated Alkyl Iodides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 5974–5977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Nishikata T; Noda Y; Fujimoto R; Sakashita T An Efficient Generation of a Functionalized Tertiary-Alkyl Radical for Copper-Catalyzed Tertiary-Alkylative Mizoroki-Heck Type Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 16372–16375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Liu C; Tang S; Liu D; Yuan J; Zheng L; Meng L; Lei A Nickel-Catalyzed Heck-Type Alkenylation of Secondary and Tertiary α-Carbonyl Alkyl Bromides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 3638–3641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Lebedev SA; Lopatina VS; Petrov ES; Beletskaya IP Condensation of Organic Bromides with Vinyl Compounds Catalysed by Nickel Complexes in the Presence of Zinc. J. Organomet. Chem 1988, 344, 253–259. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Hills ID; Netherton MR; Fu GC Toward an Improved Understanding of the Unusual Reactivity of Pd0/Trialkylphosphane Catalysts in Cross-Couplings of Alkyl Electrophiles: Quantifying the Factors That Determine the Rate of Oxidative Addition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2003, 42, 5749–5752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Clark AJ Copper Catalyzed Atom Transfer Radical Cyclization Reactions. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2016, 2016, 2231–2243. [Google Scholar]

- (33).The authors also propose a two-electron mechanistic pathway for this transformation: Mitani M; Kato I; Koyama K Photoaddition of Alkyl Halides to Olefins Catalyzed by Copper(I) Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1983, 2105, 6719–6721. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Camp JE Auto-Tandem Catalysis: Activation of Multiple, Mechanistically Distinct Process by a Single Catalyst. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2017, 2017, 425–433. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Shindoh N; Takemoto Y; Takasu K Auto-Tandem Catalysis: A Single Catalyst Activating Mechanistically Distinct Reactions in a Single Reactor. Chem.–Eur. J 2009, 15, 12168–12179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Curran DP; Chen MH; Kim D Atom-transfer cyclization. A novel isomerization of hex-5-ynyl iodides to iodomethylene cyclopentanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1986, 108, 2489–2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Tasker SZ; Standley EA; Jamison TF Recent Advances in Homogeneous Nickel Catalysis. Nature 2014, 509, 299–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Wang X; Dai Y; Gong H Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Couplings. In Ni- and Fe-Based Cross-Coupling Reactions; Correa A, Ed.; Topics in Current Chemistry Collections; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp 61–89. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Iwasaki T; Kambe N Ni-Catalyzed C–C Couplings Using Alkyl Electrophiles. In Ni- and Fe-Based Cross-Coupling Reactions; Correa A, Ed.; Topics in Current Chemistry Collections; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp 1–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Lin B-L; Liu L; Fu Y; Luo S-W; Chen Q; Guo Q-X Comparing Nickel- and Palladium-Catalyzed Heck Reactions. Organometallics 2004, 23, 2114–2123. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Millán A; Álvarez de Cienfuegos L; Miguel D; Campaña AG; Cuerva JM Water Control over the Chemoselectivity of a Ti/Ni Multimetallic System: Heck- or Reductive-Type Cyclization Reactions of Alkyl Iodides. Org. Lett 2012, 14, 5984–5987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Tang S; Liu C; Lei A Nickel-Catalysed Novel β,γ-Unsaturated Nitrile Synthesis. Chem. Commun 2013, 49, 2442–2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Rueping M; Nachtsheim BJ A Review of New Developments in the Friedel–Crafts Alkylation – From Green Chemistry to Asymmetric Catalysis. Beilstein J. Org. Chem 2010, 6, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Bowman WR; Storey JMD Synthesis Using Aromatic Homolytic Substitution—Recent Advances. Chem. Soc. Rev 2007, 36, 1803–1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Venning ARO; Bohan PT; Alexanian EJ Palladium-Catalyzed, Ring-Forming Aromatic C–H Alkylations with Unactivated Alkyl Halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 3731–3734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Dhungana RK; Shekhar KC; Basnet P; Giri R Transition Metal-Catalyzed Dicarbofunctionalization of Unactivated Olefins. Chem. Rec 2018, 18, 1314–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Fukuyama T; Nishitani S; Inouye T; Morimoto K; Ryu I Effective Acceleration of Atom Transfer Carbonylation of Alkyl Iodides by Metal Complexes. Application to the Synthesis of the Hinokinin Precursor and Dihydrocapsaicin. Org. Lett 2006, 8, 1383–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Kondo T; Sone Y; Tsuji Y; Watanabe Y Photo-, Electro-, and Thermal Carbonylation of Alkyl Iodides in the Presence of Group 7 and 8–10 Metal Carbonyl Catalysts. J. Organomet. Chem 1994, 473, 163–173. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Kondo T; Tsuji Y; Watanabe Y Photochemical Carbonylation of Alkyl Iodides in the Presence of Various Metal Carbonyls. Tet. Lett 1988, 29, 3833–3836. [Google Scholar]

- (50).McMahon CM; Renn MS; Alexanian EJ Manganese-Catalyzed Carboacylations of Alkenes with Alkyl Iodides. Org. Lett 2016, 18, 4148–4150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Brennführer A; Neumann H; Beller M Palladium-Catalyzed Carbonylation Reactions of Aryl Halides and Related Compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48, 4114–4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Sumino S; Fusano A; Fukuyama T; Ryu I Carbonylation Reactions of Alkyl Iodides through the Interplay of Carbon Radicals and Pd Catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res 2014, 47, 1563–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Sargent BT; Alexanian EJ Palladium-Catalyzed Alkoxycarbonylation of Unactivated Secondary Alkyl Bromides at Low Pressure. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 7520–7523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]