Abstract

Lithospermum erythrorhizon cell cultures have been used to produce plant secondary metabolites, as well as in biosynthetic studies. Shikonin, a representative secondary metabolite of L. erythrorhizon, was first produced industrially by dedifferentiated cell cultures in the 1980s. This culture system has since been used in research on various plant secondary metabolites. Other boraginaceaeous plant species, including Arnebia, Echium, Onosma and Alkanna, have been shown to produce shikonin, and studies have assessed shikonin regulation, including transgene expression, in these plants. This review summarizes current knowledge of shikonin production by L. erythrorhizon cell and hairy root cultures, including the historical aspect of large-scale production, and discusses future biochemical and biological research using this species.

Keywords: lithospermic acid B, Lithospermum erythrorhizon, plant cell cultures, shikonin derivatives

Introduction

Higher plants produce a large number of secondary metabolites, many of which are utilized in medicines, pesticides, spices, dyes, and fragrances. These compounds generally have complicated structures exhibiting chirality, preventing the cost-effective chemical synthesis of many of these natural compounds. Market demands may be fulfilled with field-grown or cultivated plants (Balandrin et al. 1985; Dicosmo and Misawa 1995). However, many of these plant species cannot be cultivated, and growth for many years, especially of woody plants, may be required to obtain sufficient material (Kieran et al. 1997).

Plant cell culture systems provide an effective method for the stable production of valuable natural compounds, including secondary metabolites. Efforts in the 1970s and 1980s were triggered by the industrial production, by Mitsui Chemicals (formerly Mitsui Petrochemical Industries), of shikonin by cell cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. This was the first industrial scale production of a secondary metabolite by dedifferentiated plant cells, and was followed by the large-scale production of other plant products, e.g., the production of the cancer chemotherapeutic agent paclitaxel (Taxol). The key to the successful production of shikonin derivatives is dependent on the development of a production medium tailored for shikonin. In fact, the production medium M9 was optimized solely for the production of shikonin derivatives.

The chemotaxonomy of shikonin derivatives is fairly narrow. These compounds have been detected to occur in some boraginaceaeous plants belonging to the genera Lithospermum, Arnebia, Anchusa, Echium, Onosma and Alkanna. Culture of cells from these other, non-Lithospermum plant species in M9 medium, has yielded findings similar to those observed in Lithospermum (Malik et al. 2016). This review summarizes previous research on shikonin production by L. erythrorhizon, including the mechanisms that regulate shikonin biosynthesis. In addition, this review discusses future aspects of shikonin research, especially research related to its biochemistry and cellular biology.

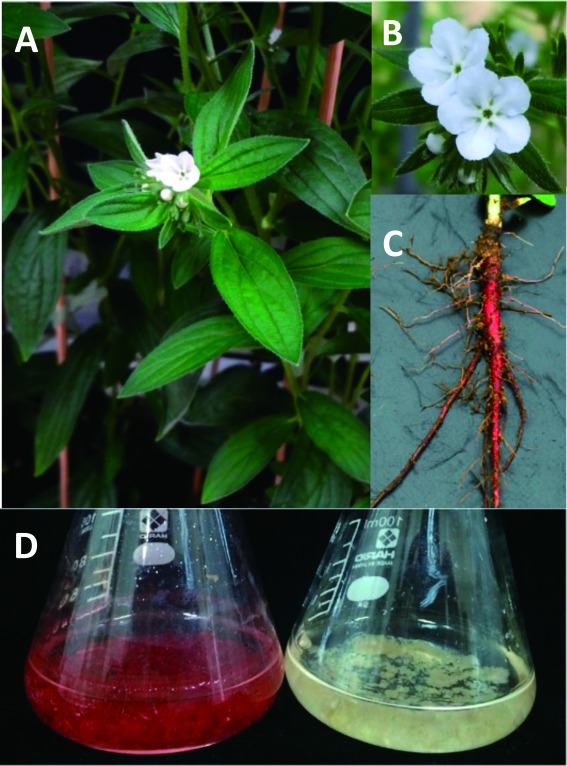

Characteristics of Lithospermum erythrorhizon and shikonin derivatives

Lithospermum erythrorhizon Sieb. et Zucc. (Boraginaceae) is a perennial herbaceous plant native to Japan, Korea, and China. Because the root bark (cork layers) of this plant contains large amounts of red naphthoquinone pigments (shikonin derivatives; Figure 1), the roots of L. erythrorhizon are red-purple in color and have been used as a dye since ancient times. Historically, the purple dye extracted from L. erythrorhizon was used to dye clothes of high-class bureaucrats in Japan. In addition, the dried roots have been used as a crude drug (Fujita and Yoshida 1937), including as an ingredient of the ointment ‘Shi-Un-Koh,’ which is used to treat skin disorders, such as wounds, burns, frostbite, swelling, and hemorrhoids (Ootsuka et al. 1972). The effectiveness of this ointment has been described in detail (Hayashi 1977a). Shikonin and its fatty acid ester derivatives, like acetylshikonin, occurring naturally in L. erythrorhizon roots, have shown various pharmacological activities, including antibacterial (Kyogoku et al. 1973; Tabata et al. 1982; Tanaka and Odani 1972), wound-healing (Hayashi 1977b), anti-inflammatory (Hayashi 1977c), tumor-inhibiting (Papageorgiou 1980; Sankawa et al. 1977), anti-angiogenic (Hisa et al. 1998), and anti-topoisomerase (Ahn et al. 1995) properties. L. erythrorhizon roots have also been used in the traditional, orally administered anti-tumor medicine ‘Shikon-Borei-Toh.’

Figure 1. Intact plant and cell suspension cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. (A) An intact L. erythrorhizon plant. The Japanese name ‘Murasaki’ is the representative name of purple color in Japanese. Flowers are white, whereas the roots are dark red to dark purple in color due to the high accumulation of shikonin derivatives in the outer bark and cork layer of the roots. The dried roots are used as a crude drug in Japanese and Chinese traditional medicines. (B) Close up of flowers. (C) Intact root of a young L. erythrorhizon plant. (D) L. erythrorhizon cells cultured in M9 medium (left) producing shikonin derivatives, and in LS medium (right), used for cell subculture.

The chemical structure of shikonin, first proposed in 1918 (Kuroda 1918), was finally determined to be an optical isomer of alkannin (Brockmann 1935), with shikonin being the R-form and alkannin the S-form (Arakawa and Nakazaki 1961). However, naturally occurring shikonin isolated from the roots and callus cultures of Lithospermum was later found to be a mixture of 84–93% R-form and 7–16% S-form (Papageorgiou et al. 1999). Other sources of natural naphthoquinone pigments include the roots of Macrotomia euchroma Pauls and Alkanna tinctoria, although these components are ester derivatives of alkannin. The absolute configurations of these compounds have little effect on their wound healing and anti-inflammatory activities (Seto et al. 1992).

The properties of shikonin derivatives are dependent on their handling. Red pigments in native form are extracted from dried materials, including roots and cultured cells. If shikonin is extracted from fresh tissues, it gradually darkens over several days, finally becoming black precipitates, which are thought to be polymers. Contact of shikonin solution with metals tends to result in the formation of insoluble complexes. For example, the ash of Camellia trees, which contains high amounts of Al, is used as a dye mordant; when mixed with shikonin solution, it forms of a beautiful purple color, which is utilized to dye clothes.

L. erythrorhizon, the representative source of shikonin, has faced the risk of extinction in recent years, and its cultivation is very difficult. Its germination rate is low, its seedlings are very susceptible to infection by viruses, and the plants are sensitive to disinfectants. According to the Amato Pharmaceutical Company, which expended considerable effort to maintain this plant species, desirable conditions for its cultivation in the field include moderate sunlight and relatively low nutrition, as well as special care to prevent its lower leaves from contact with soil upon watering (personal communication). Commercial use of this plant requires growth for three years to obtain a sufficient quantity of roots, from which crude drugs can be prepared, but growth for three years is usually very difficult. However, the yield of shikonin by chemical biosynthesis was only 0.7%, an amount insufficient for the industrial production of this compound (Terada et al. 1983).

Establishment of a high shikonin-producing line and production medium M9

Callus tissues of L. erythrorhizon were originally derived from seedlings and were grown on Linsmaier–Skoog (LS) basal (Linsmaier and Skoog 1965) agar medium containing 10−6 M 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and 10−5 M kinetin. The tissues were subsequently subcultured in the same medium containing 10−6 M indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) in place of 2,4-D and grown in the dark at 25°C, to produce the red pigmented shikonin derivatives (Mizukami et al. 1977; Tabata et al. 1974). The chemical composition of shikonin derivatives in callus cultures were the same as in the intact roots (Mizukami et al. 1978). Repeated cell selection of L. erythrorhizon callus cultures resulted in a high-yielding cell line, M18, with a shikonin content of 1.2 mg/g fresh weight of cells, a 20-fold increase over the original strain (Mizukami et al. 1978). Selection of 478 single-cell clones from a single callus yielded eight relatively stable cell lines, with an average shikonin content of 2.3 mg/g fresh weight (4.8% of dry weight), higher than the shikonin content of intact roots (ca. 1.3%) (Tabata et al. 1978). This strain was subsequently used for large-scale cell cultures.

The development of an industrial scale shikonin production system (Tabata and Fujita 1985) was dependent on the development of the M9 pigment production medium (Fujita et al. 1981a, 1982). This medium was designed by thoroughly optimizing the constituents present in White’s medium (White 1954). Essentially, M9 medium does not contain ammonium ions, which are abundant in LS medium, while having a >10-fold greater concentration of Cu2+ ion than LS medium. The process of developing M9 medium led to the identification of many chemical and physical regulatory factors (Fujita et al. 1981b; Fukui et al. 1983; Kim and Chang 1990) (Table 1). Positive regulators include methyl jasmonate (MJ), acidic oligosaccharide, Cu2+ and cold temperature (<21°C), whereas negative regulators include light, NH4+, ethanol, and high temperature (>28°C). The regulatory mechanisms are complex. For example, even in the presence of a high concentration of NH4+, as in LS medium, the presence of acidic oligosaccharide may induce shikonin production, explaining the feasibility of callus selection on LS agar medium (Tani et al. 1992, 1993). MJ is also a strong inducer of shikonin production in LS medium (Gaisser and Heide 1996; Yazaki et al. 1997). Light is the greatest inhibitor of shikonin production, almost completely inhibiting its production in M9 medium. Blue light had the strongest inhibitory effect (Yamamoto et al. 2002), suggesting the involvement of a flavin-linked enzyme in shikonin biosynthesis or of a flavoprotein in signal transduction (Tabata et al. 1993). Details of the effects of these factors and other regulatory elements are described elsewhere (Touno et al. 2000, 2005; Yazaki et al. 1999; Yoshikawa et al. 1986).

Table 1. Factors affecting shikonin production in L. erythrorhizon cell suspension cultures.

| Enhancer | Suppressor |

|---|---|

| IAA1 | Light (especially blue)1, 2 |

| Kinetin (differ with culture medium)1, 15 | 2,4-D1 |

| Streptomaycin3 | Lumiflavin (photodegradation product of FMN)4 |

| Ascorbic acid3 | p-Coumeric acid3 |

| L-Pheniylalanine3 | Benzoic acid3 |

| p-Hydroxybenzoic acid (in M9 medium)3 | Ammonium ion5 |

| Cu2+ 6 | Fe2+, Ca2+ 3 |

| Agar7 | Glutamine8 |

| Fungal clicitator (Penicillium)9 | Mevinolin (inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase)10 |

| Acidic oligosaccharides (12 to 22 mers)10 | 2-Aminoindan-2-phosphonic acid (inhibitor of PAL)11 |

| Methyl jasmonate11, 12 | Giberellin A313 |

| Ethylene14 | Ethanol (>1% in medium) |

| 1-Aminocyclopropane (ethylene precursor)14 | Silver ion (ethylene-response inhibitor)14 |

| Cold treatment (<21°C) | Aminoethoxyvinylglycine (ethylene biosynthesis inhibitor) 14 |

| High temperature (>28°C) |

1 Tabata et al. 1974; Fukui et al. 1983, 2 Yamamoto et al. 2002, 3 Mizukami et al. 1977, 1978, 4Tabata et al. 1993, 5 Fujita et al. 1981a, 6 Fujita et al. 1981b, 7 Fukui et al. 1983, 8 Yazaki et al. 1987, 9 Kim and Chang 1990, 10 Tani et al. 1992; Tani et al. 1993, 11 Gaisser and Heide 1996, 12 Yazaki et al. 1997, 13 Yoshikawa et al. 1986, 14 Touno et al. 2005, 15 Touno et al. 2000.

Large-scale production of shikonin

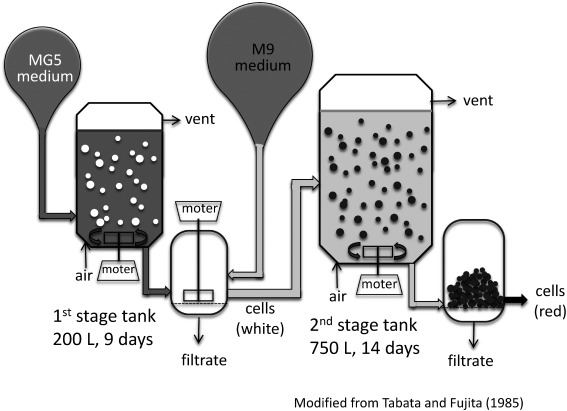

Because M9 medium was optimized solely for shikonin production, it is inferior to LS medium in promoting cell growth due to lack or low concentrations of essential nutrients, such as phosphate, in M9 medium. Industrial scale production of shikonin utilizes a “two-stage culture system” of L. erythrorhizon cells. In the first stage, cells of the high-producing strain M18 are allowed to proliferate in “growth medium”, without producing shikonin derivatives; in the second stage, these cells were transferred to M9 medium for shikonin production (Fujita et al. 1982) (Figure 2). To improve cell growth during the first stage, each component of LS medium was optimized, with the resulting “growth medium” MG-5 containing one-third of the original concentrations of Ca2+, NH4+/(NH4++NO3−), SO42−, and BO33−. The cell yield was 15% higher with MG-5 medium than with LS medium, while the use of both MG5 and M9 media in the dual-culture system resulted in an 11.5-fold increase in shikonin yield compared with growth in the LS/White dual culture system.

Figure 2. Scheme of large-scale culture set-up for production of shikonin. L. erythrorhizon cells were cultured for 9 days in MG5 medium, a modified LS medium for high cell growth. The MG5 medium was removed by filtration, and L. erythrorhizon cells were transferred to a production tank and cultured for 14 days in M9 medium. Shikonin derivatives mainly attached to the cell surface and were easily extracted from the filtered cell mass after drying.

To produce shikonin on an industrial scale, cultured cells were grown in 200 l fermentation tank containing MG5 medium for 9 days. The cultures were subsequently filtered to remove MG5 medium, and the cells were transferred to a second 750 l tank containing M9 and cultured for 14 days. The red-colored cells were harvested by filtration and dried, and the red pigment was extracted from the harvested cells with n-hexane. The chemical composition of the extracted shikonin derivatives was very similar to that of the intact roots. The differences in the relative amounts of each shikonin derivative between the extracts and the intact roots were much lower than the differences between batches of intact roots purchased in the market (Tabata and Fujita 1985). To isolate free shikonin, the extracted red pigments were hydrolyzed with 2% KOH, which turned the shikonin blue (Papageorgiou et al. 1999). The aqueous solution was acidified, and free shikonin was recovered by extraction into the organic phase. Pure shikonin was subsequently obtained by recrystallization.

Comparing the yields of shikonin by plant cultivation (48 months, shikonin content 1.4%) and cell culture (0.8 month, 20%) indicated that the latter method is about 800 times more productive than the former. Another calculation showed that a 750 l culture tank containing 600 l medium can produce 2 g/l shikonin in 2 weeks. This was equivalent to the yield over 4 years from a field of 17.6 hectares, with L. erythrorhizon plants cultivated at a density of 3.5 plants/m2, resulting in 25 g of intact roots per plant with a shikonin content of 1.0%. Shikonin production by plant cell culture was far more economical than by chemical synthesis (Terada et al. 1983, 1987). Beginning in 1984, shikonin produced by this method was used commercially in Japan for cosmetics, such as lipsticks, lotions, and soaps; at present, however, these products are not available.

Shikonin biosynthetic pathway and key regulatory enzymes

Removal of shikonin from living cells with liquid paraffin

Shikonin derivatives are highly accumulated on cell surfaces. These naphthoquinone compounds strongly inhibit many enzymes, as well as interfere with the isolation of pure RNA and DNA. Thus, biochemical studies of shikonin biosynthesis require removal of shikonin from living cultured cells prior to their homogenization. To overcome this problem, liquid paraffin was overlaid on M9 medium throughout the entire culture period to remove shikonin pigments from the cell surface (Heide and Tabata 1987a). Cell growth was not affected by the presence of 3–10 ml paraffin in 30 ml M9 medium in a conical flask, and production of shikonin derivatives was only slightly reduced. Most of the shikonin derivatives move to the paraffin layer, whereas pigments remaining on the cells can be largely reduced during early growth phase. This process was necessary to obtain active enzymes from cells producing shikonin and was also advantageous for the preparation of high quality RNA samples.

Biosynthetic pathway and its regulation

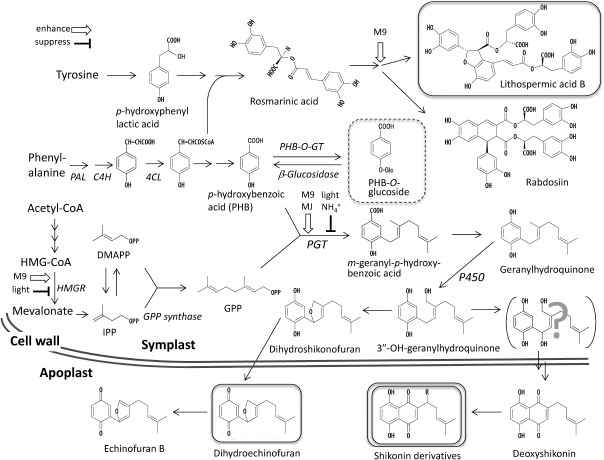

Early studies of shikonin biosynthesis involved tracer experiments in Lithospermum callus cultures, showing that shikonin was biosynthesized through the prenylation of p-hydroxybenzoic acid (PHB), which was derived from L-phenylalanine and two molecules of mevalonic acid (Inouye et al. 1979). This pathway was analogous to that of alkannin in Plagiobotrys arizonicus (Schmid and Zenk 1971). Many subsequent studies have elucidated the shikonin biosynthetic pathway (Figure 3). Two key precursors of shikonin, geranyl diphosphate (GPP) derived via the mevalonate pathway (Li et al. 1998) and PHB derived via the shikimate pathway (Inouye et al. 1979), are coupled by a geranyltransferase to yield the intermediate, m-geranyl-p-hydroxybenzolic acid (GBA) (Heide and Tabata 1987b). GBA is subsequently converted to geranylhydroquinone, followed by the hydroxylation of the geranyl chain (Yamamoto et al. 2000a). The formation of a naphthalene ring by this intermediate yields shikonin, whereas cyclicization of the geranyl moiety to form a furan ring yields dihydroechinofuran (Yazaki et al. 1986a). Thus, the formation of the naphthalene ring is regarded as critical for shikonin synthesis, although details of the latter half of the biosynthetic route have not yet been clarified. One exception is the finding that deoxyshikonin, a shikonin derivative lacking the hydroxyl residue on the side chain, is a biosynthetic precursor of acetylshikonin, as shown by tracer experiments with radio-labeled phenylalanine and deoxyshikonin (Okamoto et al. 1995), suggesting that the oxygen atom on the side chain of shikonin is introduced during the last step of shikonin formation. It is to be noted that the biosynthesis takes place in symplast, while the final products, shikonin derivatives, are accumulated in apoplast.

Figure 3. Secondary metabolism in cultured L. erythrorhizon cells. Shikonin exists in living plant cells as esters of low molecular weight fatty acids, such as acetate, whereas free shikonin is undetectable. Inhibition of shikonin production in LS medium results in the accumulation in vacuoles of the aromatic intermediate, p-hydroxybenzoic acid (PHB), as its O-glucoside. Induction of PHB geranyltransferase and inhibition of naphthalene ring formation results in the accumulation of large amounts of dihydroechinofuran, partially oxidized to the orange compound, echinofuran B, in both media. In addition to secreting these quinone metabolites, L. erythrorhizon cells produce large amounts of the phenylpropanoid tetramer, lithospermic acid B, which accumulates inside the cells. End products that show high accumulation are highlighted with squares.

Several genes encoding shikonin biosynthetic enzymes have been identified in L. erythrorhizon. With regard to the biosynthesis of PHB, cDNAs encoding genes involved in the general phenylpropanoid pathway, including phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) (Yazaki et al. 1997), cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H) (Yamamura et al. 2003), and 4-coumarate:CoA ligase (4CL) (Yazaki et al. 1995), have been isolated. These three enzymes are almost constantly expressed in cultured L. erythrorhizon cells. The enzyme involved in coupling these aromatic and prenyl substrates, PHB:geranyltransferase (PGT) (Heide and Tabata 1987b; Inouye et al. 1979), was found to require a divalent cation, with Mg2+ being optimal, while its optimal pH ranged widely from 7.1 to 9.3. This enzyme was highly specific for both substrates, PHB and GPP, and its activity was 35 times higher in shikonin-producing than in non-producing cells. This enzyme was detectable only in the microsomal fraction with a density (ρ) of 1.09–1.10 g·cm−3, similar to that of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Heide and Tabata 1987b). Because conventional purification of this membrane protein was difficult (Mühlenweg et al. 1998), we used homology-based PCR to isolate cDNAs encoding PHB-geranyltransferase. These cDNAs, LePGT-1 and -2, were isolated by using primers for the conserved amino acid sequences of the PHB-polyprenyltransferase (gene: coq2) family involved in ubiquinone biosynthesis (Yazaki et al. 2002). The transcriptional regulation of PGT was found to contribute to the regulation of shikonin biosynthesis, including enhancement by MJ and suppression by light and ammonium ions.

Regulation of the quantity of prenyl chain was found to parallel the induction of shikonin production. HMG-CoA reductase, which regulates the mevalonate pathway in many organisms, was found to catalyze a rate-limiting reaction for GPP biosynthesis in L. erythrorhizon (Köhle et al. 2002; Lange et al. 1998). The regulatory pattern of gene expression was similar to that of PGT. In contrast, GPP synthase, which catalyzes the synthesis of GPP from isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and 3,3-dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) in the presence of Mg2+ or Mn2+, was constitutively active in L. erythrorhizon cell suspension cultures (Heide 1988; Heide and Berger 1989). This enzyme differed from other plant GPP synthases, in that it localized to the cytosol and utilized as substrates IPP and DMAPP from the mevalonate pathway (Li et al. 1998). In contrast, all other GPP synthases localized to plastids and were involved in non-mevalonate pathways.

Geranylhydroquinone 3″-hydroxylase, which provides a common intermediate for shikonin and dihydroechinofuran from geranylhydroquinone (GHQ), was identified in suspension cultures of non-pigmented cells (Yamamoto et al. 2000a). This enzyme, which introduces a hydroxyl residue to the isoprenoid side chain of GHQ at position 3″, localizes to the microsomal fraction. Further analyses suggested that this enzyme was a cytochrome P450 dependent monooxygenase with high affinity for GHQ (Km=1.5 µM).

Although these enzyme activities have been reported involved in shikonin biosynthesis, the genes encoding these proteins have not yet been identified. Proteins involved in this pathway include GPP synthase (Sommer et al. 1995), PHB O-glucosyl transferase (Bechthold et al. 1991; Li et al. 1997; Yazaki et al. 1995) and geranylhydroquinone 3″-hydroxylase (Yamamoto et al. 2000a). Molecular biological approaches are required to isolate these genes, including their regulation by light in cultured L. erythrorhizon cells.

Gene determination by subtractive hybridization

The finding, that shikonin production is reversibly regulated by irradiation with light, suggested cDNAs potentially related to shikonin production in cultured L. erythrorhizon cells could be isolated by conventional subtractive hybridization. The genes preferentially expressed in the dark were designated L. erythrorhizon dark-inducible (LEDI) genes. These genes included the oxidoreductase-like genes LEDI-3 through -5 (Yazaki et al. 1999), as well as LEDI-2, which encodes a small polypeptide of 114 amino acids and shows the strictest dark-selectivity (Yazaki et al. 2001). These dark-selective genes also included a fragment of LePGT. However, biosynthetic enzymes encoded by the genes described in the above paragraph were not found.

We therefore utilized a more powerful technique, PCR-selected subtraction, to search for dark-inducible genes. Of about 800 candidate clones, 240 showed dark-induction. These included several biosynthetic genes previously identified by other methods, including genes encoding LePGTs, HMG-CoA reductase and LEDIs (our unpublished data). In addition, more systematic transcriptome information has been obtained by RNA-seq analysis. We intend to expand this analysis to identify genes involved in the later regulation of shikonin biosynthesis.

Other metabolites highly accumulated in L. erythrorhizon cells

Intact L. erythrorhizon plants produce caffeic acid derivatives, such as rosmarinic acid (Figure 3), and cultured L. erythrorhizon cells were shown to produce this caffeic acid dimer (Mizukami et al. 1992, 1993). Moreover, transfer of L. erythrorhizon cells from LS medium to M9 medium resulted in an increase in production of lithospermic acid B, a caffeic acid tetramer, comparable to the level of shikonin derivatives (Yamamoto et al. 2000b). In addition, lower amounts of other caffeic acid derivatives like rabdosiin were detected in M9 medium (Fukui et al. 1984; Yamamoto et al. 2000c). A striking difference, however, was seen upon illumination, which strongly inhibited the production of shikonin but not of lithospermic acid B (Yamamoto et al. 2002). Another difference between lithospermic acid B and shikonin derivatives were their sites of accumulation, with lithospermic acid B accumulating inside cells, presumably in vacuoles, in contrast to shikonin derivatives, which accumulate on cell surfaces. Lithospermic acid B is biosynthesized by branching from 4-coumaric acid or its CoA ester, however, thus sharing a common phenylpropanoid pathway with shikonin (Figure 4).

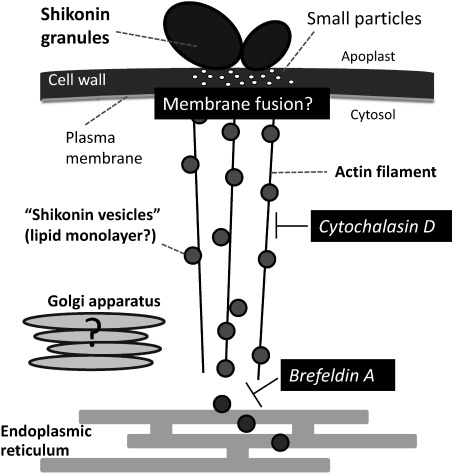

Figure 4. Schematic model of shikonin secretion from L. erythrorhizon cells. Electron microscopic studies suggested that the shikonin-producing cell contained electron-dense vesicles derived from endoplasmic reticulum. These vesicles may cross the plasma membrane for excretion by unknown mechanisms, with shikonin derivatives accumulating as red granules on cell walls. Many small particles were found beneath the shikonin-rich red granules attached to the cell surface. Because shikonin derivatives are highly hydrophobic, these intracellular vesicles are regarded as lipid monolayers, similar to oil bodies (Tatsumi et al. 2016).

Secretion of Shikonin

Intracellular biosynthesis and transport of shikonin

The aromatic shikonin precursor PHB is derived from shikimate, which localizes to plastids, whereas another key intermediate, GPP, is produced in the cytosol via the mevalonate pathway. The enzyme coupling both substrates, LePGT, localizes to the ER. In LS medium or under illumination in M9 medium, however, the expression of PGT is strongly suppressed, with excess amounts of PHB being glucosylated and accumulating in vacuoles (Yazaki et al. 1986b, 1995). UDPG:PHB glucosyltransferase was purified from shikonin-free L. erythrorhizon cell cultures (Bechthold et al. 1991) and shown to localize in the cytosol (Yazaki et al. 1995). If shikonin production ceases, the biosynthesis of GPP, another key intermediate, is downregulated at the HMG-CoA reductase step, thereby avoiding the over-accumulation of GPP. The geranylated intermediate is hydroxylated by cytochrome P450, but the steps and cellular location involved in ring formation, resulting in the production of shikonin or dihydroechinofuran, have not yet been determined (Figure 3).

Little information is available about the transport mechanisms of shikonin derivatives. An early electron microscopic analysis of shikonin-producing L. erythrorhizon cells suggested that shikonin pigments or their intermediates accumulated in “secretion vesicles”, which originate from electron dense, spherical swellings formed in highly elongated rough ER (Tabata et al. 1982; Tsukada and Tabata 1984). These secretion vesicles are thought to be present in the microsomal fraction (ρ=1.09–1.10 g·cm−3) containing PHB-geranyltransferase activity (Yamaga et al. 1993), because in vitro incubation of 14C-labeled deoxyshikonin with these vesicles resulted in the generation of 14C-labeled shikonin and 14C-labeled shikonin esters, including acetyl- and β-hydroxyisovaleryl-shikonin, indicating that these vesicles contain enzymes responsible for both the hydroxylation and acylation of deoxyshikonin (Okamoto et al. 1995). Moreover, granules attached to the cell surface were thought to contain shikonin derivatives secreted from these cells (Tsukada and Tabata 1984). Because these electron micrographs were taken after chemical fixation, the granules appeared to be empty, suggesting that lipophilic substances are removed by the dehydration process but that these structures are surrounded by membranes. Thus, intracellular shikonin vesicles were thought to fuse to plasma membranes and form extracellular granules containing high amounts of shikonin derivatives (Tabata 1996) (Figure 4).

There are, however, several drawbacks to this model of shikonin derivative secretion. First, as shikonin derivatives are very hydrophobic, these shikonin vesicles are surrounded by a phospholipid monolayer rather than a lipid bilayer like oil bodies. Those oleophilic particles may not simply fuse to plasma membranes, because fusion would result in a strong phospholipid imbalance between the inner and outer leaflets. Second, this model cannot explain the origin of the large quantities of membrane lipids observed in large extracellular granules or the high shkonin production rate, amounting to about 10% of cell weight. Third, this model cannot explain how these shikonin-containing structures on plasma membranes cross the cell wall, as such images were not observed.

Our recent report may, however, provide a key to the mechanism underlying the secretion of shikonin derivatives. Using hairy roots of L. erythrorhizon (Figure 5), a model system closer to intact roots than dedifferentiated cells, we observed similar extracellular granules on epidermal cells, along with many small vesicle-like structures inside cell walls (Tatsumi et al. 2016). This study also showed that shikonin secretion was stopped by depolymerization of actin filaments or inhibition of the adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-ribosylation factor/guanine nucleotide exchange factor (ARF/GEF) system, suggesting that shikonin secretion utilizes, at least partly, the same pathway as the sec system (Tatsumi et al. 2016) (Figure 4).

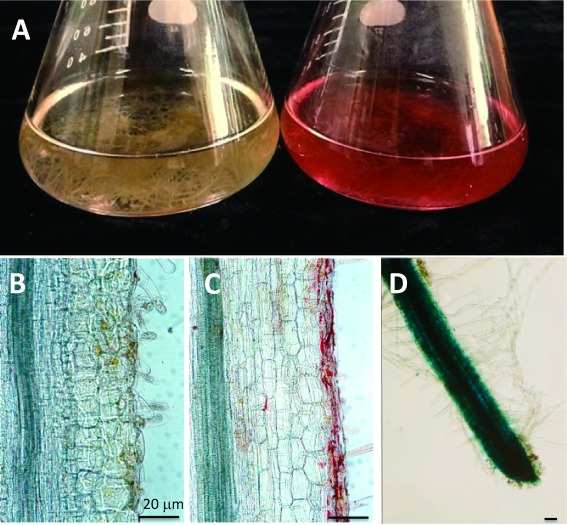

Figure 5. Hairy roots of L. erythrorhizon. (A) Hairy root cultures in M9 medium under illumination (left) and in the dark (right). (B, C) Longitudinal sections of a hairy root grown under illumination (B) and in the dark (C). Shikonin derivatives accumulatd in epidermal cells. (D) Whole mount picture of a GUS transformant of an L. erythrorhizon hairy root. Scale bars are 20 µm.

To date, two genes have been reported to be associated with the shikonin secretion process. LeDI-2, which was isolated by subtractive hybridization, encodes a small, membrane-bound polypeptide. The expression pattern of LEDI-2 paralleled that of shikonin production. Suppression of LeDI-2 by antisense RNA also suppressed the shikonin accumulation, but did not affect membrane-bound LePGT enzyme activity (Yazaki et al. 2001). Another small protein, LEPS-2, containing 184 amino acids, was cloned by differential display between shikonin-producing and non-producing strains (Yamamura et al. 2003). LEPS-2 expression was also closely associated with shikonin production. Moreover, LEPS-2 was found to be a cell wall protein, suggesting its involvement in the accumulation of shikonin pigment in cell walls. To date, however, details of the biochemical functions of LEDI-2 and LEPS-2 remain unknown.

Stable transformation of L. erythrorhizon

Establishment of a stable transformation method is in general a hurdle for non-model plants, such as L. erythrorhizon, but it can improve the productivity of secondary metabolites by genetic engineering and enable reverse genetic methods for the functional analyses of genes. Attempts to stably transform cultured cells have been unsuccessful. In 1998, we utilized intact shoots and Agrobacterium rhizogenes (ATC C 15834) to introduce desired genes into hairy roots of L. erythrorhizon (Yazaki et al. 1998) (Figure 5). Briefly, a foreign gene was introduced into A. rhizogenes prior to infecting the plants; following infection, this gene would integrate into the plant genome, in parallel with the rol genes of the Ri plasmid. Root tissue is the specific site for the production and accumulation of shikonin derivatives in intact plants, and the synthesis of shikonin derivatives has been detected in hairy roots (Shimomura et al. 1991). Moreover, no special apparatus was needed for transformation via direct infection with A. rhizogenes. A binary vector containing a gene encoding β-glucuronidase (GUS), driven by a CaMV35S promoter, as well as a gene encoding hygromycin phosphotransferase (HPT) as a selection marker was constructed to show that a desired foreign gene could be expressed in L. erythrorhizon hairy roots. The survival rate on hygromycin plates depended on the gene subcloned into the binary vector, being 20%, 25%, and 50% for GUS (Yazaki et al. 1998), ubiC (Sommer et al. 1999), and LEDI-2-antisense (Yazaki et al. 2001), respectively. Histochemical analyses of the transgenic hairy roots using the GUS reporter gene showed that the CaMV35S promoter was active in most of the root tissues (Figure 5).

Shikonin production patterns and responses to various regulatory factors of hairy roots in M9 medium are generally similar to those observed in dedifferentiated cells (Yazaki et al. 1998), suggesting that hairy roots provided an alternative plant material to study shikonin biosynthesis and transport in L. erythrorhizon. For example, this transformation system was utilized in a reverse-genetic study to show that the LeDI-2 gene was involved in shikonin production (Yazaki et al. 2001). Practical differences between cultured cells and hairy root cultures are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Differences between cultured cells and hairy root of L. erythrorhizon.

| · | In LS liquid medium, hairy roots can produce shikonin, which gradually darkens and finally becomes black precipitates (our unpublished data). |

| · | In M9 medium, induction of shikonin synthesis by hairy roots is more rapid than that of cultured cells (Yazaki et al. 2001). |

| · | Induction of LEDI-2 gene expression in hairy roots is more rapid than that of cultured cells (Yazaki et al. 2001). |

| · | In hairy roots cultures, the addition of n-hexadecane drastically increases shikonin productivity compared to the cell suspension cultures (Sim et al. 1994). |

| · | M9 medium, which is most effective for shikonin production in cultured cells, is not optimal for shikonin production by hairy roots due to the shortage of nourishment (Fukui et al. 1999). |

Future aspects

Current ‘omics’ technologies provide very powerful tools to analyze expressed genes and proteins as well as synthesized metabolites. We have used these techniques to thoroughly analyze biological events that occur in cultured cells and the hairy roots of L. erythrorhizon. Transcriptomics data in several shikonin-producing boraginaceaeous plants were recently published (Wu et al. 2017). Active competition in this field will accelerate the progress in understanding the pathways and regulatory mechanisms of shikonin biosynthesis and transport.

Natural plant products may include large numbers of valuable, potentially useful resources. Along with conventional plant cell culture systems involved in the production of compounds like shikonin, natural compounds may be produced by metabolic engineering. For example, foreign genes can be introduced into various host plants, or expressed in microorganisms (Yazaki 2004). Although the production of these secondary metabolites requires basic knowledge of their biosynthetic pathways, the pathways involved in the biosynthetic reactions of certain secondary metabolites have not been completely elucidated. Further basic studies are required for successful metabolic engineering and synthetic biology. Moreover, efforts are needed to determine the mechanisms involved in the accumulation of these natural products in plant cells, because secondary metabolites often accumulate in specific organelles like vacuoles, or in specific cell layers such as the epidermis, and can be transported from source cells to sink organs (Yazaki 2005, 2006). Integrated studies of the biosynthesis and transport of these secondary metabolites may improve future metabolic engineering.

Acknowledgments

This review article is associated with The JSPCMB Award for Distinguished Research in 2016. I am grateful to the Editor-in-Chief of Plant Biotechnology for the kind invitation to submit this review. I am also grateful to Amato Pharmaceutical Products Ltd. and Takeda Garden for Medicinal Plant Conservation in Kyoto for providing intact L. erythrorhizon plants. I also thank a former Ph.D. student, Ms. Kyoko Yamamoto, who helped in summarizing the contents of this review. This work was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 16K13087 and an additional grant from Mission Research of RISH, Kyoto University.

Abbreviations

- 2,4-D

2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid

- 4CL

4-coumarate:CoA ligase

- ARF

adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-ribosylation factor

- C4H

cinnamate 4-hydroxylase

- DMAPP

3,3-dimethylallyl diphosphate

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- GBA

m-geranyl-p-hydroxybenzolic acid

- GEF

guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- GHQ

geranylhydroquinone

- GPP

geranyl diphosphate

- GUS

β-glucuronidase

- HPT

hygromycin phosphotransferase

- IPP

isopentenyl diphosphate

- LEDI

L. erythrorhizon dark-inducible

- LEPS

L. erythrorhizon pigment callus-specific gene

- LS

Linsmaier-Skoog

- MJ

methyl jasmonate

- PAL

phenylalanine ammonia-lyase

- PGT

PHB:geranyltransferase

- PHB

p-hydroxybenzoic acid

References

- Ahn BZ, Baik KU, Kweon GR, Lim K, Hwang BD (1995) Acylshikonin analogs: Synthesis and inhibition of DNA topoisomerase-I. J Med Chem 38: 1044–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa H, Nakazaki M (1961) Absolute configuration of shikonin and alkannin. Chem Ind 25: 947 [Google Scholar]

- Balandrin MF, Klocke JA, Wurtele ES, Bollinger WH (1985) Natural plant chemicals: Sources of industrial and medicinal materials. Science 228: 1154–1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechthold A, Berger U, Heide L (1991) Partial purification, properties, and kinetic studies of UDP-glucose: p-hydroxybenzoate glucosyltransferase from cell cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Arch Biochem Biophys 288: 39–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmann H Jr (1935) Die Konstitution des Alkannins, Shikonins und Alkannnans. Justus Liebigs Ann Chem 521: 1–47 (in German) [Google Scholar]

- Dicosmo F, Misawa M (1995) Plant cell and tissue culture: Alternatives for metabolite production. Biotechnol Adv 13: 425–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita N, Yoshida Y (1937) Ueber die Anatomie von Radix Lithospermi. Yakugaku Zasshi 57: 368–391 [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y, Hara Y, Suga C, Morimoto T (1981a) Production of shikonin derivatives by cell suspension cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. 2. A new medium for the production of shikonin deivatives. Plant Cell Rep 1: 61–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y, Hara Y, Ogino T, Suga C (1981b) Production of shikonin derivatives by cell suspension cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon: 1. Effects of nitrogen sources on the production of shikonin derivatives. Plant Cell Rep 1: 59–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y, Tabata M, Nishi A, Yamada Y (1982) New medium and production of secondary compounds with the two-staged culture method. In: Fujiwara A (ed) Plant Tissue Culture 1982. Maruzen, Tokyo, pp 312–313

- Fukui H, Feroj Hansan AFM, Ishii Y, Tanaka M (1999) An envelope-shaped film culture vessel for shikonin production by Lithospermum erythrorhizon hairy root cultures. Plant Biotechnol 16: 171–174 [Google Scholar]

- Fukui H, Yazaki K, Tabata M (1984) Two phenolic acids from Lithospermum erythrohizon cell suspension cultures. Phytochemistry 23: 2398–2399 [Google Scholar]

- Fukui H, Yoshikawa N, Tabata M (1983) Induction of shikonin formation by agar in Lithospermum erythrorhizon cell suspension cultures. Phytochemistry 22: 2451–2453 [Google Scholar]

- Gaisser S, Heide L (1996) Inhibition and regulation of shikonin biosynthesis in suspension cultures of Lithospermum. Phytochemistry 41: 1065–1072 [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M (1977a) Pharmacological studies of Shikon and Tooki. (1) Pharmacological effects of the water and ether extracts. Nippon Yakurigaku Zasshi 73: 177–191 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M (1977b) Pharmacological studies of Shikon and Tooki. (2) Pharmacological effects of the pigment components, Shikonin and acetylshikonin. Nippon Yakurigaku Zasshi 73: 193–203 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M (1977c) Pharmacological studies of Shikon and Tooki. (3) Effect of topical application of the ether extracts and Shiunko on inflammatory reactions. Nippon Yakurigaku Zasshi 73: 205–214 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heide L (1988) Geranylpyrophosphate synthase from cell cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. FEBS Lett 237: 159–162 [Google Scholar]

- Heide L, Berger U (1989) Partial purification and properties of geranyl pyrophosphate synthase from Lithospermum erythrorhizon cell cultures. Arch Biochem Biophys 273: 331–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heide L, Tabata M (1987a) Enzyme activities in cell-free extracts of shikonin-producing Lithospermum erythrorhizon cell suspension cultures. Phytochemistry 26: 1645–1650 [Google Scholar]

- Heide L, Tabata M (1987b) Geranylpyrophosphate p-hydroxybenzoate geranyltransferase activity in extracts of Lithospermum erythrorhizon cell cultures. Phytochemistry 26: 1651–1655 [Google Scholar]

- Hisa T, Kimura Y, Takada K, Suzuki F, Takigawa M (1998) Shikonin, an ingredient of Lithospermum erythrorhizon, inhibits angiogenesis in vivo and in vitro. Anticancer Res 18(2A): 783–790 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye H, Ueda S, Inoue K, Matsumura H (1979) Biosynthesis of shikonin in callus cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Phytochemistry 18: 1301–1308 [Google Scholar]

- Kieran PM, MacLoughlin PF, Malone DM (1997) Plant cell suspension cultures: Some engineering considerations. J Biotechnol 59: 39–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DJ, Chang HN (1990) Increased shikonin production in Lithospermum erythrorhizon suspension cultures with in situ extraction and fungal cell treatment (elicitor). Biotechnol Lett 12: 443–446 [Google Scholar]

- Köhle A, Sommer S, Yazaki K, Ferrer A, Boronat A, Li SM, Heide L (2002) High level expression of chorismate pyruvate-lyase (UbiC) and HMG-CoA reductase in hairy root cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Plant Cell Physiol 43: 894–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda T (1918) Tokyo Kagaku Zasshi 39: 1051–1115 (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kyogoku K, Terayama H, Tachi Y, Suzuki T, Komatsu M (1973) Constituents of “shikon.” II. Comparison of contents, constituents, and antibacterial effect of fat soluble fraction between “nanshikon” and “koshikon.” Shoyakugaku Zasshi 27: 31–36 (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Lange BM, Severin K, Bechthold A, Heide L (1998) Regulatory role of microsomal 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase for shikonin biosynthesis in Lithospermum erythrorhizon cell suspension cultures. Planta 204: 234–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SM, Hennig S, Heide L (1998) Shikonin: A geranyl diphosphate-derived plant hemiterpenoid formed via the mevalonate pathway. Tetrahedron Lett 39: 2721–2724 [Google Scholar]

- Li SM, Wang ZX, Heide L (1997) Purification of UDP-glucose: 4-hydroxybenzoate glucosyltransferase from cell cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Phytochemistry 46: 27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsmaier EM, Skoog F (1965) Organic growth factor requirements of tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant 18: 100–127 [Google Scholar]

- Malik S, Bhushan S, Sharma M, Ahuja PS (2016) Biotechnological approaches to the production of shikonins: A critical review with recent updates. Crit Rev Biotechnol 36: 327–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizukami H, Konoshima M, Tabata M (1977) Effect of nutritional factors on shikonin derivative formation in Lithospermum callus cultures. Phytochemistry 16: 1183–1186 [Google Scholar]

- Mizukami H, Konoshima M, Tabata M (1978) Variation in pigment production in Lithospermum erythrorhizon callus cultures. Phytochemistry 17: 95–97 [Google Scholar]

- Mizukami H, Ogawa T, Ohashi H, Ellis BE (1992) Induction of rosmarinic acid biosynthesis in Lithospermum erythrorhizon cell suspension cultures by yeast extract. Plant Cell Rep 11: 480–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizukami H, Tabira Y, Ellis BE (1993) Methyl jasmonate-induced rosmarinic acid biosynthesis in Lithospermum erythrorhizon cell suspension cultures. Plant Cell Rep 12: 706–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mühlenweg A, Melzer M, Li SM, Heide L (1998) 4-Hydroxybenzoate 3-geranyltransferase from Lithospermum erythrorhizon: Purification of a plant membrane-bound prenyltransferase. Planta 205: 407–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto T, Yazaki K, Tabata M (1995) Biosynthesis of shikonin derivatives from L-phenylalanine via deoxyshikonin in Lithospermum cell cultures and cell free extract. Phytochemistry 38: 83–88 [Google Scholar]

- Ootsuka Y, Yakazu M, Shimizu T (1972) Kanpou Shinryou Iten. Nanzandou, Tokyo (in Japanese)

- Papageorgiou VP (1980) Naturally occurring isohexenylnaphthazarin pigments: A new class of drugs. Planta Med 38: 193–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou VP, Assimopoulou AN, Couladouros EA, Hepworth D, Nicolaou KC (1999) The chemistry and biology of alkaninn, shikonin, and related naphthazarin natural products. Angew Chem Int Ed 38: 270–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankawa U, Ebizuka Y, Miyazaki T, Isomura Y, Otsuka H, Shibata S, Inomata M, Fukuoka F (1977) Antitumor activity of shikonin and its derivatives. Chem Pharm Bull 25: 2392–2395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid HV, Zenk MH (1971) p-Hydroxybenzoic acid and mevalonic acid as precursors of the plant naphthoquinone alkannin. Tetrahedron Lett 12: 4151–4155 [Google Scholar]

- Seto Y, Motoyoshi S, Nakamura H, Imuta J, Ishitoku T, Isayama S (1992) Effect of shikonin and its derivatives, pentaacetylated shikonin (MDS-004) on granuloma formation and delayed-type allergy in experimental animals. Pharmaceut Soc Jpn (Yakugaku Zasshi) 112: 259–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura K, Sudo H, Saga H, Kamada H (1991) Shikonin production and secretion by hairy root cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Plant Cell Rep 10: 282–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim SJ, Kim DJ, Chang HN (1994) Shikonin production by extractive cultivation in transformed-suspension and hairy root cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Ann N Y Acad Sci 745: 442–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer S, Kohle A, Yazaki K, Shimomura K, Bechthold A, Heide L (1999) Genetic engineering of shikonin biosynthesis hairy root cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon transformed with the bacterial ubiC gene. Plant Mol Biol 39: 683–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer S, Severin K, Camara B, Heide L (1995) Intracellular localization of geranylpyrophosphate synthase from cell cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Phytochemistry 38: 623–627 [Google Scholar]

- Tabata M (1996) The mechanism of shikonin biosynthesis in Lithospermum cell cultures. Plant Tissue Culture Lett 13: 117–125 [Google Scholar]

- Tabata M, Fujita Y (1985) Production of shikonin by plant cell cultures. In: Zaitlin M, Day P, Hollaender A (eds) Biotechnology in Plant Science. Orlando, pp 207–218

- Tabata M, Mizukami H, Hiraoka N, Konoshima M (1974) Pigment formation in callus cultures of Lithospermum erythrohizon. Phytochemistry 13: 927–932 [Google Scholar]

- Tabata M, Ogino T, Yoshioka N, Hiraoka N (1978) Frontiers of Plant Tissue Culture 1978. University of Calgary Press, Albera, pp 213–222

- Tabata M, Tsukada M, Fukui H (1982) Antimicrobial activity of quinone derivatives from Echium lycopsis callus cultures. Planta Med 44: 234–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata M, Yazaki K, Nishikawa Y, Yoneda F (1993) Inhibition of shikonin biosynthesis by photodegradation products of FMN. Phytochemistry 32: 1439–1442 [Google Scholar]

- Tabata M, Yoshikawa N, Tsukada M, Fukui H (1982) Localization and regulation of shikonin formation in the cultured cells of Lithospermum erythrorhizon In: Fujiwara A (ed) Plant Tissue Culture 1982. Maruzen, Tokyo, pp 335–336

- Tanaka Y, Odani T (1972) Pharmacodynamic study on “shiunko”. 1. Antibacterial effect of “shiunko”. Pharmaceut Soc Jpn 95: 525–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani M, Fukui H, Shimomura M, Tabata M (1992) Structure of endogenous oligogalacturonides inducing shikonin biosynthesis in Lithospermum cell cultures. Phytochemistry 31: 2719–2723 [Google Scholar]

- Tani M, Takeda K, Yazaki K, Tabata M (1993) Effects of oligogalacturonides on biosynthesis of shikonin in Lithospermum cell cultures. Phytochemistry 34: 1285–1290 [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumi K, Yano M, Kaminade K, Sugiyama A, Sato M, Toyooka K, Aoyama T, Sato F, Yazaki K (2016) Characterization of shikonin derivative secretion in Lithospermum erythrorhizon hairy roots as a model of lipid-soluble metabolite secretion from plants. Front Plant Sci 7: 1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada A, Tanoue Y, Hatada A, Sakamoto H (1983) Total synthesis of shikalkin [(±)-shikonin]. J Chem Soc Chem Commun Issue 18: 987–988 [Google Scholar]

- Terada A, Tanoue Y, Hatada A, Sakamoto H (1987) Synthesis of shikalkin (±-shikonin) and related compounds. Bull Chem Soc Jpn 60: 205–213 [Google Scholar]

- Touno K, Harada K, Yoshimatsu K, Yazaki K, Shimomura K (2000) Shikonin derivative formation on the stem of cultured shoots in Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Plant Cell Rep 19: 1121–1126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touno K, Tamaoka J, Ohashi Y, Shimomura K (2005) Ethylene induced shikonin biosynthesis in shoot culture of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Plant Physiol Biochem 43: 101–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada M, Tabata M (1984) Intracellular localization and secretion of naphthoquinone pigments in cell cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Planta Med 50: 338–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RP (1954) The Cultivation of Animal and Plant Cells. Ronald Press, New York

- Wu FY, Tang CY, Guo YM, Bian ZW, Fu JY, Lu GH, Qi JL, Pang YJ, Yang YH (2017) Transcriptome analysis explores genes related to shikonin biosynthesis in Lithospermeae plants and provides insights into Boraginales’ evolutionary history. Sci Rep 7: 4477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaga Y, Nakanishi K, Fukui H, Tabata M (1993) Intracellular localization of p-hydroxybenzoate geranyltransferase, a key enzyme involved in shikonin biosynthesis. Phytochemistry 32: 633–636 [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H, Inoue K, Li SM, Heide L (2000a) Geranylhydroquinone 3″-hydroxylase, a cytochrome P-450 monooxygenase from Lithospermum erythrorhizon cell suspension cultures. Planta 210: 312–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H, Inoue K, Yazaki K (2000b) Caffeic acid oligomers in Lithospermum erythrorhizon cell suspension cultures. Phytochemistry 53: 651–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H, Yazaki K, Inoue K (2000c) Simultaneous analysis of shikimate-derived secondary metabolites in Lithospermum erythrorhizon cell suspension cultures by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl 738: 3–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H, Zhao P, Yazaki K, Inoue K (2002) Regulation of lithospermic acid B and shikonin production in Lithospermum erythrorhizon cell suspension cultures. Chem Pharm Bull 50: 1086–1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamura Y, Sahin FP, Nagatsu A, Mizukami H (2003) Molecular cloning and characterization of a cDNA encoding a novel apoplastic protein preferentially expressed in a shikonin-producing callus strain of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Plant Cell Physiol 44: 437–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazaki K (2004) Chapter 43: Natural products and metabolites. In: Klee H, Paul Christou P (eds) Handbook of Plant Biotechnology. John Wiley & Sons Inc., New York, pp 811–857

- Yazaki K (2005) Transporters of secondary metabolites. Curr Opin Plant Biol 8: 301–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazaki K (2006) ABC transporters involved in the transport of plant secondary metabolites. FEBS Lett 580: 1183–1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazaki K, Fukui H, Kikuma M, Tabata M (1987) Regulation of shikonin production by glutamine in Lithospermum erythrorhizon cell cultures. Plant Cell Rep 6: 131–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazaki K, Fukui H, Tabata M (1986a) Isolation of the intermediates and related metabolites of shikonin biosynthesis from Lithospermum erythrorhizon cell cultures. Chem Pharm Bull 34: 2290–2293 [Google Scholar]

- Yazaki K, Fukui H, Tabata M (1986b) Accumulation of p-O-β-D-glucosylbenzoic acid and its relation to shikonin biosynthesis in Lithospermum cell cultures. Phytochemistry 25: 1629–1632 [Google Scholar]

- Yazaki K, Inushima K, Kataoka M, Tabata M (1995) Intracellular localization of UDPG: p-hydroxybenzoate glucosyltransferase and its reaction product in Lithospermum cell cultures. Phytochemistry 38: 1127–1130 [Google Scholar]

- Yazaki K, Kataoka M, Honda G, Severin K, Heide L (1997) cDNA cloning and gene expression of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase in Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 61: 1995–2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazaki K, Kunihisa M, Fujisaki T, Sato F (2002) Geranyl diphosphate: 4-hydroxybenzoate geranyltransferase from Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Cloning and characterization of a key enzyme in shikonin biosynthesis. J Biol Chem 277: 6240–6246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazaki K, Matsuoka H, Shimomura K, Bechthold A, Sato F (2001) A novel dark-inducible protein, LeDI-2, and its involvement in root-specific secondary metabolism in Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Plant Physiol 125: 1831–1841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazaki K, Matsuoka H, Ujihara T, Sato F (1999) Shikonin biosynthesis in Lithospermum erythrorhizon: Light-induced negative regulation of secondary metabolism. Plant Biotechnol 16: 335–342 [Google Scholar]

- Yazaki K, Ogawa A, Tabata M (1995) Isolation and characterization of two cDNAs encoding 4-coumarate:CoA ligase in Lithospermum cell cultures. Plant Cell Physiol 36: 1319–1329 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazaki K, Takeda K, Tabata M (1997) Effects of methyl jasmonate on shikonin and dihydroechinofuran production in Lithospermum cell cultures. Plant Cell Physiol 38: 776–782 [Google Scholar]

- Yazaki K, Tanaka S, Matsuoka H, Sato F (1998) Stable transformation of Lithospermum erythrorhizon by Agrobacterium rhizogenes and shikonin production of the transformants. Plant Cell Rep 18: 214–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa N, Fukui H, Tabata M (1986) Effect of gibberellin A3 on shikonin production in Lithospermum callus cultures. Phytochemistry 25: 621–622 [Google Scholar]