Abstract

A colonoscopy is considered to be the standard diagnostic test used to detect early colorectal lesions. Detection rates are expected to improve with optimised visualisation. A systematic review and network meta-analysis was conducted to evaluate detection efficiency in several colonoscopic modalities. Relevant articles were identified in searches of the PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane Library databases. The modalities, comprising of standard-definition white light (SDWL), high-definition white light (HDWL), narrow-band imaging (NBI), autofluorescence imaging (AFI), PENTAX image enhanced technology (i-SCAN), Fuji Intelligent Color Enhancement (FICE), dye-based chromoendoscopy and novel image enhanced systems, including blue laser imaging (BLI) and linked color imaging (LCI), were compared to identify the most efficient modalities that could be used to detect colorectal lesions. Odds ratios (ORs) and mean differences (MDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. As a result, 40 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Overall, in the network meta-analyses, NBI (OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.04–1.58), FICE (OR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.11–1.77), chromoendoscopy (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.22–1.93) and AFI (OR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.07–2.87) were significantly better compared with SDWL at identifying adenoma in patients, and chromoendoscopy also proved significantly superior to HDWL (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.06–1.60). In pairwise analyses, it was demonstrated that chromoendoscopy was significantly superior to HDWL at detecting the number of polyps (MD, −1.11; 95% CI, −1.46, −0.76) and flat lesions (MD, −0.30; 95% CI, −0.49, −0.10) per subject. Additionally, FICE detected a significantly greater number of subjects with polyps (OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.64–0.96) and NBI was significantly better at detecting the number of subjects with flat lesions (OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.60–0.99) compared with HDWL. Based on the meta-analysis, NBI, FICE and AFI were significantly better compared with SDWL at detecting patients with adenoma. Additionally, chromoendoscopy was significantly better than SDWL and HDWL at detecting the number of colorectal adenoma, however additional studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Keywords: detection rate, efficiency, colorectal lesions, endoscopic modalities, colonoscopy

Introduction

Colorectal lesions are found in symptomatic and asymptomatic patient populations during colonoscopy procedures (1). The majority of sporadic colorectal cancers are hypothesised to develop from adenomatous polyps and villous adenomas, which accumulate genetic alterations over a period of years via environmental influences (2).

The colonoscopic removal of polyps has been a mainstay in colorectal cancer prevention following a 67–76% reduction in the incidence of colorectal cancer (3,4). Therefore, an improvement in detection rates of adenomas or polyps would aid in decision making regarding endoscopic treatment, including resection strategy and appropriate surveillance intervals following colonoscopies (5).

High-quality colonoscopies are mandatory to prevent adenoma recurrence and colorectal cancer (3). In the past few years, technical advances have been developed with the purpose of improving detection rates of colorectal lesions, including adenoma, polyps and flat lesions. Image-enhanced endoscopy (IEE) has been demonstrated to facilitate the detection and characterization of polyps and especially nonpolypoid colorectal neoplasms. Indigo carmine is the most frequently used dye in colonoscopies as it deposits in depressed lesions (4,5). Virtual chromoendoscopies have emerged as an effective contrast enhancement technology without the limitation of preparing dyes and applying them through the colonoscope working channel (2,5).

However, colonic lesions are often subtle in appearance and difficult to identify with conventional optical colonoscopy (6). Enhancing mucosal contrast, either by dye use or advanced optical imaging, may improve the detection of adenomatous lesions, but the question as to which endoscopic technique is preferable for detecting lesions remains controversial (6). Previous conventional meta-analyses either could not clearly determine the efficacy of different endoscopic techniques to detect adenomas or other kinds of lesions, or failed to integrate all the evidence (7,8). The aim of the current study was to compare the standard-definition white-light endoscopy (SDWL), high-definition white-light endoscopy (HDWL), chromoendoscopy (CHRO), narrow-band imaging (NBI), autofluorescence imaging (AFI), Fuji Intelligent Color Enhancement (FICE) colonoscopy and i-SCAN colonoscopy to determine the modalities that yielded the highest number of colorectal lesions identified per subject and subjects with colorectal lesions using a network meta-analysis. Additionally, the current study sought to provide a systematic review about endoscopic modalities and new-generation image-enhanced endoscopy facilitates, including blue laser imaging (BLI) and linked color imaging (LCI).

Materials and methods

Search strategy

A literature search of PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed), Embase (www.embase.com) and the Cochrane Library (www.cochranelibrary.com) database was conducted for all studies comparing the detection of colon adenomas/polyps using SDWL, HDWL, AFI, FICE, NBI, i-SCAN, BLI, LCI and CHRO in patients undergoing colonoscopies. The reference lists of included studies, relevant reviews and meta-analyses selected from the electronic database search were also manually searched to avoid missing relevant studies. In cases where studies presented duplicate data, the most recent study was used in the current analysis.

Study selection

Studies were eligible for the current meta-analysis if they met the following criteria: i) Randomised controlled trials or prospective cohort studies; ii) assessed for the detection rate of adenomas/polyps using SDWL, HDWL, AFI, FICE, NBI, BLI, LCI, i-SCAN and CHRO regardless of indication (i.e., screening, surveillance or symptoms). Studies were excluded for the following reasons: i) Included participants with inflammatory bowel diseases or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer; ii) data was inadequate (the content of literature research was not related to polyps/adenoma) for extraction; or iii) designed as a review, editorial, comment or meta-analysis. Two reviewers (SL and LL) independently reviewed the studies derived from the searches to determine whether they were eligible for inclusion and obtained the full articles of the included studies.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from each eligible study: i) Study characteristics, including the start and end date of the study, location, study design, and publication status of the study; ii) participants' characteristics, including the total number of patients, age, inclusion and exclusion criteria and indication for colonoscopy; iii) type of colonoscopy; iv) the outcome of the study, including the total number of lesions and adenomas or polyps, the number of participants with adenomas or polyps, the size and type of colorectal lesions.

Study quality assessment and statistical methods

Two reviewers (LF and OH) independently assessed the quality and risk of bias of the included studies with Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS) (9). The tool is based on a 14-item questionnaire, with each item having the response of ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘unclear’. Any discrepancies in interpretation were resolved by discussion. Network meta-analyses combine direct and indirect evidence for all relative treatment effects and provide estimates with maximum power (10). The R2WinBUGS Package (version 2.1–21; http://cran.r-project.org/) was used to conduct a Bayesian analysis that combined data from multiple randomised control trials (11). Network meta-analyses are better at integrating different types of evidence compared with conventional pairwise meta-analyses, however this type of analysis leads to inevitable heterogeneity (10). Thus, pairwise meta-analyses were also conducted for SDWL and HDWL endoscopy, comparing them with other types of techniques to supplement the network meta-analysis. RevMan 5.3 software (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used to conduct pairwise meta-analyses. For continuous outcomes, the relative effect sizes were calculated as standardised mean differences (SMDs), as previously described (10). For binary outcomes, relative effect sizes were calculated as odds ratios (ORs). The two types of effect sizes were reported with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The I2 statistic is a test used to quantify heterogeneity and it was used to calculate the proportion of variation due to heterogeneity rather than by chance, between the included studies. Values of I2 >50% indicated that heterogeneity existed. When statistical heterogeneity was identified, individual study characteristics were examined and a sensitivity analysis was performed on the primary outcomes. In the sensitivity analysis, after excluding a relatively low-quality study, the combined effect was re-estimated to evaluate the source of heterogeneity (10).

Results

Study description and quality

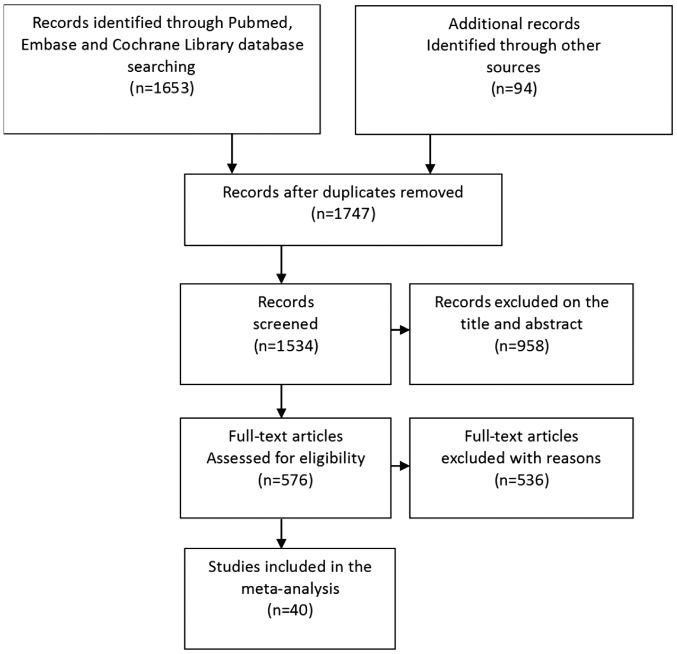

From the initial search, a total of 1,747 potentially relevant studies were identified between December 1949 and December 2017. A total of 958 studies were excluded based on the title and abstract, as they were not relevant to the meta-analysis conducted in the current study, and the full text of the rest of the initial search studies were obtained for further assessment (Fig. 1). A total of 54 studies were excluded as they were review articles, meta-analyses or case reports; 146 studies that were not randomised controlled trials were excluded; and 335 studies that did not have enough data to be extracted were excluded. Only one study about BLI met the inclusion criteria, however an effective meta-analysis could not be conducted and was excluded due to insufficient data. Finally, 40 studies with a total of 14,109 participants were included, which provided enough data for the analyses conducted in the current study (1,12–50). All studies were reported in English and more than one endoscopic technique was assessed in several studies.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the literature search conducted.

Of the 40 studies included, 37 studies were described in full-paper articles and 3 studies were published as abstracts. A total of 12 studies provided data about SDWL, 32 about HDWL, 14 about NBI, nine about CHRO, five about AFI, six about FICE and two about i-SCAN. A total of 23 studies focused on the differentiation of diminutive lesions or flat adenomas. A total of 27 studies compared the number of detected adenomas, 19 compared the number of adenomas detected per participant, 12 compared the number of polyps detected per participant, 29 compared the proportion of patients with at least one adenoma detected and 20 compared the proportion of patients with at least one polyp detected.

The score of the included studies was assessed by the QUADAS tool. Of the 40 studies, 36 were considered to be high quality whilst the remaining four studies were considered to be poor quality and were subsequently removed from the meta-analysis (data not shown). Three of the four relatively poor-quality reports were only published as an abstract.

Network meta-analysis of adenoma detection

A Bayesian network analysis was conducted on the data of subjects with adenoma and for adenoma number detection, which comprised of sufficient controlled studies to avoid excessive heterogeneity (Table I). A total of 29 studies featuring 10,805 patients were included in the analysed group of subjects with adenoma. NBI (OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.04–1.58), FICE (OR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.11–1.77), CHRO (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.22–1.93) and AFI (OR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.07–2.89) were significantly more efficient at identifying patients with adenoma compared with SDWL, and CHRO (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.06–1.60) was also significantly better at identifying patients with adenoma compared with HDWL. However, other endoscopic techniques were not better than HDWL as all 95% CI included 1.00. A total of 27 studies featuring 10,094 patients were included in the group in which the number of adenoma detected was analysed. However, no significant differences were identified among these seven targeted endoscopic techniques in this subgroup; all 95% CI included 1.00.

Table I.

Network meta-analyses of adenoma detection.

| Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Endoscopic modalities | Patients with adenoma | Number of adenoma/subject detected |

| SDWL | ||

| HDWL | 1.18 (0.98–1.39) | 1.17 (0.86–1.55) |

| NBI | 1.29 (1.04–1.58)a | 1.10 (0.74–1.62) |

| FICE | 1.39 (1.11–1.77)a | 1.09 (0.71–1.63) |

| CHRO | 1.53 (1.22–1.93)a | 1.10 (0.73–1.58) |

| i-SCAN | 1.52 (0.81–2.61) | 1.66 (0.74–3.23) |

| AFI | 1.81 (1.07–2.87)a | 1.64 (0.83–2.95) |

| HDWL | ||

| NBI | 1.09 (0.95–1.25) | 0.95 (0.72–1.25) |

| FICE | 1.17 (0.98–1.40) | 0.94 (0.66–1.28) |

| CHRO | 1.30 (1.06–1.60)a | 0.95 (0.64–1.38) |

| i-SCAN | 1.28 (0.70–2.14) | 1.43 (0.68–2.61) |

| AFI | 1.54 (0.89–2.47) | 1.42 (0.68–2.47) |

| NBI | ||

| FICE | 1.08 (0.88–1.32) | 1.01 (0.66–1.44) |

| CHRO | 1.20 (0.94–1.50) | 1.03 (0.63–1.54) |

| i-SCAN | 1.18 (0.62–2.05) | 1.54 (0.67–3.05) |

| AFI | 1.42 (0.82–2.32) | 1.53 (0.69–2.83) |

| FICE | ||

| CHRO | 1.11 (0.88–1.38) | 1.04 (0.64–1.60) |

| i-SCAN | 1.10 (0.59–1.88) | 1.57 (0.66–3.27) |

| AFI | 1.32 (0.74–2.11) | 1.55 (0.69–2.78) |

| CHRO | ||

| i-SCAN | 1.00 (0.51–1.73) | 1.56 (0.68–3.25) |

| AFI | 1.19 (0.68–1.93) | 1.54 (0.70–3.00) |

| i-SCAN | ||

| AFI | 1.30 (0.56–2.57) | 1.13 (0.40–2.46) |

P<0.05. AFI, autofluorescence imaging; CHRO, chromoendoscopy; FICE, Fuji Intelligent Color Enhancement; HDWL, high-definition white light; NBI, narrow-band imaging; SDWL, standard-definition white light.

Pairwise meta-analysis of colorectal lesions detection

To explain the heterogeneity and to supply comprehensive comparisons of the network analysis, pairwise studies were also performed. In the analysis group comparing the number of adenomas per subject, 19 studies featuring 7,727 subjects were included. Two studies (1,45) compared HDWL with CHRO and revealed that CHRO was significantly better than HDWL (MD, −0.44; P=0.0004). Additionally, the number of adenomas per subject was no more likely to be identified using NBI (P=0.78), FICE (P=0.77), i-SCAN (P=0.54) and AFI (P=0.98) compared with HDWL, with MD ranging from −0.09 to 0. In these analysis groups, significant statistical heterogeneity was observed as P≤0.05, however I2 for HDWL-CHRO was 78 (P=0.03), which indicates that there are differences between these studies.

A total of 12 studies featuring 4,409 subjects used number of polyps per patient as the outcome. In these studies, CHRO with a specific dye was significantly superior to SDWL (MD, −0.73; 95% CI, −1.13, −0.33) and HDWL (MD, −1.11; 95% CI, −1.46, −0.76) at detecting the number of polyps per patient. CHRO with a specific dye was also significantly superior at determining the number of flat lesions per subject compared with SDWL (MD, −0.15; 95% CI, −0.30, −0.00) and HDWL (MD, −0.30; 95% CI, −0.49, −0.10), without significant heterogeneity (1,33,44,45).

CHRO detected more subjects with polyps compared with SDWL (MD, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.32–0.57) and HDWL (MD, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.11–0.78), and FICE detected more subjects with polyps compared with HDWL (MD, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.64–0.96). HDWL was significantly more efficient at identifying subjects with flat lesions compared with NBI (OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.60–0.99). Studies involving subjects with >3 adenomas were also analysed, however no significant differences were identified between SDWL, HDWL, FICE, NBI and CHRO.

HDWL proved to be a more effective at detecting diminutive lesions compared with SDWL (OR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.39–0.68). However, HDWL was less effective at detecting flat lesions compared with SDWL (OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.09–2.17). Traditional CHRO seemed to be slightly better at detecting diminutive lesions compared with HDWL (OR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.19–0.63) and FICE (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.35–0.75), however sufficient evidence was lacking (Table II) (32,38).

Table II.

Pairwise meta-analyses of colorectal lesions in different endoscopic modalities.

| Heterogeneity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endoscopic modalities | Number of studies | Number of subjects | Mean Difference/Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | I2 (%) | P-value |

| Adenomas per subject | ||||||

| SD-HD | 3 | 1,140 | −0.06a (−0.19–0.08) | 0.4 | 55 | 0.11 |

| SD-CHRO | 2 | 248 | −0.21a (−0.44–0.01) | 0.07 | 59 | 0.12 |

| HD-CHRO | 2 | 960 | −0.44a (−0.68–0.20) | 0.0004 | 78 | 0.03 |

| HD-FICE | 3 | 1,587 | −0.01a (−0.09–0.07) | 0.77 | 0 | 0.58 |

| HD-AFI | 2 | 194 | 0.00a (−0.12–0.13) | 0.98 | 0 | 0.44 |

| HD-i-SCAN | 1 | 237 | −0.09a (−0.38–0.20) | 0.54 | N/A | N/A |

| HD-NBI | 6 | 3,137 | −0.01a (−0.07–0.06) | 0.78 | 0 | 0.86 |

| Polyps per subject | ||||||

| SD-HD | 3 | 1,140 | −0.11a (−0.30–0.08) | 0.26 | 48 | 0.14 |

| SD-CHRO | 2 | 248 | −0.73a (−1.13–0.33) | 0.0003 | 0 | 0.46 |

| HD-CHRO | 2 | 960 | −1.11a (−1.46–0.76) | <0.00001 | 0 | 0.55 |

| HD-NBI | 2 | 696 | 0.09a (−0.06–0.23) | 0.25 | 0 | 0.32 |

| HD-FICE | 1 | 359 | −0.21a (−0.54–0.12) | 0.21 | N/A | N/A |

| HD-i-SCAN | 1 | 237 | −0.21a (−0.54–0.12) | 0.89 | N/A | N/A |

| Flat lesions per subject | ||||||

| SD-CHRO | 1 | 198 | −0.15a (−0.30–0.00) | 0.04 | N/A | N/A |

| HD-CHRO | 2 | 960 | −0.30a (−0.49–0.10) | 0.003 | 62 | 0.1 |

| HD-NBI | 3 | 859 | 0.46a (−0.30–1.23) | 0.24 | 96 | <0.00001 |

| Subjects with polyp | ||||||

| SD-HD | 4 | 1,374 | 0.86b (0.69–1.07) | 0.17 | 0 | 0.46 |

| SD-CHRO | 4 | 767 | 0.43b (0.32–0.57) | <0.00001 | 0 | 0.86 |

| HD-FICE | 3 | 1,805 | 0.78b (0.64–0.96) | 0.02 | 0 | 0.41 |

| HD-CHRO | 2 | 600 | 0.29b (0.11–0.78) | 0.01 | 81 | 0.02 |

| HD-NBI | 5 | 3,477 | 0.86b (0.63–1.18) | 0.34 | 76 | 0.002 |

| HD-i-SCAN | 1 | 234 | 0.66b (0.40–1.11) | 0.12 | N/A | N/A |

| Subjects with flat lesion | ||||||

| HD-NBI | 3 | 1,413 | 0.77b (0.60–0.99) | 0.05 | 43 | 0.17 |

| Subjects with more than three adenomas | ||||||

| SD-HD | 2 | 750 | 0.93b (0.31–2.81) | 0.9 | 73 | 0.06 |

| SD-CHRO | 2 | 458 | 0.47b (0.22–1.03) | 0.06 | 47 | 0.17 |

| HD-FICE | 2 | 1,459 | 0.90b (0.54–1.50) | 0.68 | 15 | 0.28 |

| HD-NBI | 3 | 2,096 | 1.22b (0.87–1.72) | 0.25 | 0 | 0.45 |

| Flat-lesion number | ||||||

| SD-HD | 3 | 1,022 | 1.54b (1.09–2.17) | 0.01 | 0 | 0.72 |

| SD-CHRO | 2 | 192 | 0.76b (0.41–1.40) | 0.37 | 36 | 0.21 |

| SD-AFI | 1 | 152 | 0.64b (0.21–1.98) | 0.44 | N/A | N/A |

| HD-FICE | 4 | 1,023 | 0.96b (0.65–1.42) | 0.85 | 0 | 0.41 |

| HD-NBI | 9 | 2,862 | 0.89b (0.62–1.26) | 0.5 | 68 | 0.002 |

| HD-CHRO | 1 | 1,680 | 0.54b (0.44–0.66) | <0.00001 | N/A | N/A |

| HD-AFI | 2 | 246 | 0.65b (0.36–1.15) | 0.14 | 9 | 0.29 |

| Diminutive lesion number | ||||||

| SD-HD | 3 | 1,024 | 0.51b (0.39–0.68) | <0.00001 | 0 | 0.86 |

| HD-FICE | 3 | 938 | 0.94b (0.69–1.28) | 0.69 | 0 | 0.64 |

| HD-NBI | 6 | 2,372 | 0.94b (0.78–1.14) | 0.53 | 0 | 0.43 |

| HD-CHRO | 1 | 202 | 0.34b (0.19–0.63) | 0.0006 | N/A | N/A |

| HD-AFI | 1 | 173 | 0.50b (0.24–1.06) | 0.07 | N/A | N/A |

| FICE-CHRO | 1 | 507 | 0.52b (0.35–0.75) | 0.0006 | N/A | N/A |

Mean Difference

Odds Ratio. AFI, autofluorescence imaging; CHRO, chromoendoscopy; FICE, Fuji Intelligent Color Enhancement; HDWL, high-definition white light; NBI, narrow-band imaging; SDWL, standard-definition white light.

Discussion

Early detection of cancers and adenomas of the colon is the key to reducing the incidence rate of colorectal carcinoma. According to several reports, 10–15% of lesions, especially small and flat lesions, remained undiagnosed following conventional colonoscopy, even by experienced colonoscopists (26,41). Therefore, image-enhanced endoscopic techniques, including CHRO, FICE, NBI, AFI and i-SCAN, have come into practice to increase the detection rate of colorectal lesions, and the new-generation image-enhanced techniques have been demonstrated to be superior to conventional techniques in polyp visibility (51,52). Based on the results of the current study, newly developed techniques could greatly enhance the early detection of lesions during a colonoscopy. CHRO could be useful for the detection of colorectal adenomas, especially in the flat and diminutive lesions compared with the other analysed techniques.

Chromoscopy with indigo carmine has been demonstrated to be effective in detecting neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions, with accuracy ranging from 84–97% (53). Individuals with a history or a family history of colorectal cancer, or who have more than three colorectal adenomas, have a high risk of developing cancer (3). Therefore, the aim of colonoscopies is to accurately detect the number of adenomas in patients. Two studies suggested that CHRO was good at detecting adenomas in high-risk populations (25,44). However, the studies' design of tandem colonoscopy, which is usually performed by only one colonoscopist, might induce investigator-dependent bias and thus influence the outcome analysis. That the same colonoscopist performed both of the targeted colonoscopic techniques, and the same region of the colon was again investigated, may influence the CHRO results. Le Rhun et al (33) suggested that the high adenoma detection rates may be due to HDWL used in combination with CHRO. The current study revealed that CHRO was superior to HDWL in the detection of colorectal lesions and that high definition should be one of several factors leading to an improved detection rate.

The duration of withdrawal time, a potential contributory factor, demonstrated a positive association with the adenoma detection rate (ADR) (54). CHRO is known to be a time-consuming technique (6). It is theoretically possible that the increased withdrawal time could result in enhanced adenoma detection. Flat and diminutive lesions are easily missed if adequate time and attention are not devoted to their detection. As flat adenomas present a more likely increased risk for malignant progression compared with polyploid adenomas, it is especially imperative to detect them (52). The Lau and Sung study (55) demonstrated that CHRO improved the detection of flat lesions comparing with HDWL with magnification.

Despite being expensive and time-consuming, CHRO remains irreplaceable, especially in the screening of high-risk patients (55). With more new image enhancement techniques, including BLI, LCI and new NBI (51,52,56), it was demonstrated that the detection rate of colon lesions may be improved without sacrificing image sharpness and brightness.

The efficiency of FICE for the ADR was controversial as well (12,16,17). The data of the current analysis demonstrated that FICE improved the detection of polyps in (P=0.02), however it did not improve the detection of total adenomas and flat lesions. However, in medium-risk individuals presenting for screening or diagnostic colonoscopy, the ADR of FICE was superior to SDWL colonoscopy and equivalent to conventional CHRO (38). When including high-risk individuals undergoing postoperative (sigmoidectomy or rectal anterior resection) follow-up colonoscopy, FICE missed significantly fewer lesions compared with HDWL (24 vs. 46%) (30). Considering the shorter duration of inspection and the outstanding efficiency of FICE for distinguishing between neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions (crucial for determining therapeutic strategies), and the lower miss rate of FICE in high-risk individuals, the authors of the current study hypothesise that it may be appropriate to perform FICE in the screening or diagnostic colonoscopy of high-risk individuals.

Aminalai et al (12) revealed that SDWL imaging using high image resolution technology is just as accurate as techniques that improve contrast enhanced colonoscopies, such as FICE; however the outcome may also be influenced by experience (16). The majority of the studies included in the current analysis were performed by experienced endoscopists and no significant differences in the detection of adenomas were identified between FICE and other endoscopic techniques. Additional studies will be required to identify whether FICE could improve detection rates when performed by less experienced endoscopists.

Novel colonoscopic technologies were developed to improve adenoma detection and to decrease miss rates. Ikematsu et al (51) reported the mean number of adenomas per patient was significantly higher in the BLI group compared with that in the HDWL group, however the ADR was not significantly higher. Thus, the authors of the current study hypothesise that BLI and LCI is a promising modality for the detection of diminutive lesions, especially polypoid and flat lesions, however further studies are required.

NBI has been studied extensively with the ADR results reported in much more detail; positive and negative results have been reported (21,27,49). In the current network analysis, no significant differences in the ADR were identified between NBI and other endoscopic techniques, however NBI seemed to be of value in identifying patients with flat lesions (P=0.05). NBI may be beneficial in colonoscopies, but several factors may contribute to its reduced effectiveness in randomised controlled trials focusing on NBI (19,21,27).

As mentioned, a colonoscopist's experience may have a considerable impact on the detection rate, thus this may also be true with NBI. The efficiency of NBI in the detection of adenomas may not be evident if the colonoscopist does not have sufficient training with an NBI system. Combining data from multiple operators may potentially conceal colonoscopists who have high ADRs using novel technologies or those who perform worse (19). Similar to other endoscopic technologies, NBI also has poorer brightness and resolution compared with HDWL. However, recently these factors were improved by the new-generation video processor system (EVIS LUCERA ELITE) when compared with the previous NBI system (56). Ogiso et al (56) used the polyp visibility scores to evaluate the detection efficiency and demonstrated that NBI with the ELITE system were significantly higher compared with those of HDWL.

The learning effect itself may also be a reason to evaluate the efficiency of NBI. In a UK study, the ADR of the NBI group was consistently 25%; however, the ADR of the HDWL group rose continuously, from 8–26.5% in each consecutive 100 patients (50). The increasing ADR with HDWL may have been as a result of some form of learning effect following the use of the NBI contrast-enhancement technique. The elements of NBI and novel NBI techniques emphasise the contrast of mucosal microvessels, which potentially obscure surface detail to influence the detection of adenomas with NBI (56). Therefore, it suggested that NBI may be helpful under optimal conditions and in right-sided colons (19,40,50).

As yet, few studies have investigated the efficiency of i-SCAN in the colon. Hong et al (24) suggested that i-SCAN failed to prevent missed polyps or to improve adenoma detection compared with HDWL, but further research is required to support this view.

In the current analysis, only two studies that compared the efficiency between i-SCAN and WL met the criteria for inclusion of the current study. With the resulting dearth of subjects, the sample size may be too small to meaningfully compare the ADR efficiency between i-SCAN and WL. Additionally, the optimal settings for the modes of image enhancement of i-SCAN, including contrast, surface enhancement and tone enhancement, remain unclear. This limitation may be a reason to conduct further studies into the efficiency of the ADR of i-SCAN.

Matsuda et al (34), who examined the left and right sides of the colon separately, demonstrated a higher detection rate of adenomas and flat adenomas with AFI compared with WL. In addition, a study demonstrated a significant improvement in the detection of adenomas in a high-risk group of patients (39). However, the results of the current analysis revealed that AFI was no better at detection compared with other endoscopic techniques with the exception of SDWL, regardless of the lesion's shape. The duration and difficulty of operation may limit the use of AFI in detecting colonic lesions (34,35).

The current meta-analysis has several limitations. Marked heterogeneity in some of the analysis groups decreased the power of the findings, with respect to patients' details and endoscopic factors. The current analysis included average-risk individuals undergoing screening endoscopy, high-risk individuals with positive faecal occult blood tests and patients with adenomas on previous endoscopies. The endoscopic factors were the differences in withdrawal time among the studies and the bias generated by a non-blinded design where the same endoscopist performed the two techniques being compared in certain studies, as was predictable from the nature of the intervention. Studies investigating i-SCAN and AFI were scarce, leading to less meaningful results about these novel endoscopic techniques. Additionally, lesion location, morphology and pathology are all important aspects of colonoscopies, however the data were not clearly described in the majority of individual studies.

In conclusion, the current meta-analyses of 40 studies demonstrated that NBI, FICE and AFI were significantly better compared with SDWL in identifying patients with adenomas. Furthermore, CHRO, as a time-consuming technique requiring endoscopy and the spraying of dye, was superior to SDWL and HDWL colonoscopies in the detection of adenomas, polyps and flat lesions. NBI appeared effective in detecting subjects with flat lesions, whereas FICE effective at detecting polyps. The authors of the current study would not suggest applying CHRO in the screening of average-risk individuals, but it may be the first choice to apply in high-risk individuals as it efficiently detected colorectal lesions. Digital colonoscopy methods, including NBI or FICE, could be used to improve neoplasm diagnosis rates and be potentially efficacious at detecting colorectal lesions, including polyps and flat, diminutive adenomas. Additionally, novel image enhanced system, including BLI, LCI and the novel NBI system, were also revealed to have great potential in the detection of colorectal lesions.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The current study was funded by the Beijing Medical and Health Foundation (grant no. YWJKJJHKYJJ-B17303-Z06).

Availability of data and materials

The analyzed data sets generated during the study are available in the published article.

Authors' contributions

LL designed the study and prepared the manuscript. YO and HS collected the data and performed the majority of analyses. SL performed the pairwise analysis. FH, QP and PC provided technical support. HY and SD revised the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Kahi CJ, Anderson JC, Waxman I, Kessler WR, Imperiale TF, Li X, Rex DK. High-definition chromocolonoscopy vs. high-definition white light colonoscopy for average-risk colorectal cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1301–1307. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muto T, Bussey HJ, Morson BC. The evolution of cancer of the colon and rectum. Cancer. 1975;36:2251–2270. doi: 10.1002/cncr.2820360944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, O'Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, Waye JD, Schapiro M, Bond JH, Panish JF, et al. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1977–1981. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahi CJ, Imperiale TF, Juliar BE, Rex DK. Effect of screening colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:770–775. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.12.030. quiz 711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O'Brien MJ, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Hankey BF, Shi W, Bond JH, Schapiro M, Panish JF, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:687–696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuda T, Ono A, Sekiguchi M, Fujii T, Saito Y. Advances in image enhancement in colonoscopy for detection of adenomas. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:305–314. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin XF, Chai TH, Shi JW, Yang XC, Sun QY. Meta-analysis for evaluating the accuracy of endoscopy with narrow band imaging in detecting colorectal adenomas. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:882–887. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Omata F, Ohde S, Deshpande GA, Kobayashi D, Masuda K, Fukui T. Image-enhanced, chromo, and cap-assisted colonoscopy for improving adenoma/neoplasia detection rate: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:222–237. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2013.863964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Bossuyt PM, Kleijnen J. The development of QUADAS: A tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dias S, Welton NJ, Sutton AJ, Ades AE. A generalised linear modelling framework for pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. NICE DSU Technical Support Document. 2011;2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sturtz S, Ligges U, Gelman A. R2WinBUGS: A package for running WinBUGS from R. J Stat Softw. 2005;12:1–16. doi: 10.18637/jss.v012.i03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aminalai A, Rösch T, Aschenbeck J, Mayr M, Drossel R, Schröder A, Scheel M, Treytnar D, Gauger U, Stange G, et al. Live image processing does not increase adenoma detection rate during colonoscopy: A randomized comparison between FICE and conventional imaging (Berlin Colonoscopy Project 5, BECOP-5) Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2383–2388. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bisschops R, Tejpar S, Willekens H, De Hertogh G, Van Cutsem E. Su1432 I-SCAN detects more polyps in lynch syndrome (HNPCC) patients: A prospective controlled randomized back-to-back study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:AB330. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.03.857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boparai KS, van den Broek FJ, van Eeden S, Fockens P, Dekker E. Increased polyp detection using narrow band imaging compared with high resolution endoscopy in patients with hyperplastic polyposis syndrome. Endoscopy. 2011;43:676–682. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooker JC, Saunders BP, Shah SG, Thapar CJ, Thomas HJ, Atkin WS, Cardwell CR, Williams CB. Total colonic dye-spray increases the detection of diminutive adenomas during routine colonoscopy: A randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:333–338. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.126908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cha JM, Lee JI, Joo KR, Jung SW, Shin HP. A prospective randomized study on computed virtual chromoendoscopy versus conventional colonoscopy for the detection of small colorectal adenomas. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2357–2364. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung SJ, Kim D, Song JH, Kang HY, Chung GE, Choi J, Kim YS, Park MJ, Kim JS. Comparison of detection and miss rates of narrow band imaging, flexible spectral imaging chromoendoscopy and white light at screening colonoscopy: A randomised controlled back-to-back study. Gut. 2014;63:785–791. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung SJ, Kim D, Song JH, Park MJ, Kim YS, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. Efficacy of computed virtual chromoendoscopy on colorectal cancer screening: A prospective, randomized, back-to-back trial of Fuji Intelligent Color Enhancement versus conventional colonoscopy to compare adenoma miss rates. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.East JE, Ignjatovic A, Suzuki N, Guenther T, Bassett P, Tekkis PP, Saunders BP. A randomized, controlled trial of narrow-band imaging vs. high-definition white light for adenoma detection in patients at high risk of adenomas. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e771–e778. doi: 10.1111/codi.12014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.East JE, Stavrindis M, Thomas-Gibson S, Guenther T, Tekkis PP, Saunders BP. A comparative study of standard vs. high definition colonoscopy for adenoma and hyperplastic polyp detection with optimized withdrawal technique. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:768–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glenn T, Hoffman BJ, Romagnuolo J, Hawes RH. Does narrow band imaging (NBI) enhance colon polyp detection? Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:AB277. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(05)01243-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gross SA, Buchner AM, Crook JE, Cangemi JR, Picco MF, Wolfsen HC, DeVault KR, Loeb DS, Raimondo M, Woodward TA, Wallace MB. A comparison of high definition-image enhanced colonoscopy and standard white-light colonoscopy for colorectal polyp detection. Endoscopy. 2011;43:1045–1051. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helbig CD, Rex DK. Narrow band imaging (NBI) versus white-light (WL) for colon polyp detection using high definition (HD) colonoscopes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:AB213. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.03.525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong SN, Choe WH, Lee JH, Kim SI, Kim JH, Lee TY, Kim JH, Lee SY, Cheon YK, Sung IK, et al. Prospective, randomized, back-to-back trial evaluating the usefulness of i-SCAN in screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:1011–1021.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hüneburg R, Lammert F, Rabe C, Rahner N, Kahl P, Büttner R, Propping P, Sauerbruch T, Lamberti C. Chromocolonoscopy detects more adenomas than white light colonoscopy or narrow band imaging colonoscopy in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer screening. Endoscopy. 2009;41:316–322. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1119628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurlstone DP, Cross SS, Slater R, Sanders DS, Brown S. Detecting diminutive colorectal lesions at colonoscopy: A randomised controlled trial of pan-colonic versus targeted chromoscopy. Gut. 2004;53:376–380. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.029868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikematsu H, Saito Y, Tanaka S, Uraoka T, Sano Y, Horimatsu T, Matsuda T, Oka S, Higashi R, Ishikawa H, Kaneko K. The impact of narrow band imaging for colon polyp detection: A multicenter randomized controlled trial by tandem colonoscopy. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1099–1107. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0575-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inoue T, Murano M, Murano N, Kuramoto T, Kawakami K, Abe Y, Morita E, Toshina K, Hoshiro H, Egashira Y, et al. Comparative study of conventional colonoscopy and pan-colonic narrow-band imaging system in the detection of neoplastic colonic polyps: A randomized, controlled trial. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:45–50. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2125-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaltenbach T, Friedland S, Soetikno R. A randomised tandem colonoscopy trial of narrow band imaging versus white light examination to compare neoplasia miss rates. Gut. 2008;57:1406–1412. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.137984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kiriyama S, Matsuda T, Nakajima T, Sakamoto T, Saito Y, Kuwano H. Detectability of colon polyp using computed virtual chromoendoscopy with flexible spectral imaging color enhancement. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2012;2012:596303. doi: 10.1155/2012/596303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuiper T, van den Broek FJ, Naber AH, Van Soest EJ, Scholten P, Mallant-Hent RCh, van den Brande J, Jansen JM, van Oijen AH, Marsman WA, et al. Endoscopic trimodal imaging detects colonic neoplasia as well as standard video endoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1887–1894. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lapalus MG, Helbert T, Napoleon B, Rey JF, Houcke P, Ponchon T, Société Française d'Endoscopie Digestive Does chromoendoscopy with structure enhancement improve the colonoscopic adenoma detection rate? Endoscopy. 2006;38:444–448. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le Rhun M, Coron E, Parlier D, Nguyen JM, Canard JM, Alamdari A, Sautereau D, Chaussade S, Galmiche JP. High resolution colonoscopy with chromoscopy versus standard colonoscopy for the detection of colonic neoplasia: A randomized study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsuda T, Saito Y, Fu KI, Uraoka T, Kobayashi N, Nakajima T, Ikehara H, Mashimo Y, Shimoda T, Murakami Y, et al. Does autofluorescence imaging videoendoscopy system improve the colonoscopic polyp detection rate?-A pilot study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1926–1932. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moriichi K, Fujiya M, Sato R, Watari J, Nomura Y, Nata T, Ueno N, Maeda S, Kashima S, Itabashi K, et al. Back-to-back comparison of auto-fluorescence imaging (AFI) versus high resolution white light colonoscopy for adenoma detection. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paggi S, Radaelli F, Amato A, Meucci G, Mandelli G, Imperiali G, Spinzi G, Terreni N, Lenoci N, Terruzzi V. The impact of narrow band imaging in screening colonoscopy: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1049–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pellisé M, Fernández-Esparrach G, Cárdenas A, Sendino O, Ricart E, Vaquero E, Gimeno-García AZ, de Miguel CR, Zabalza M, Ginès A, et al. Impact of wide-angle, high-definition endoscopy in the diagnosis of colorectal neoplasia: A randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1062–1068. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.06.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pohl J, Lotterer E, Balzer C, Sackmann M, Schmidt KD, Gossner L, Schaab C, Frieling T, Medve M, Mayer G, et al. Computed virtual chromoendoscopy versus standard colonoscopy with targeted indigocarmine chromoscopy: A randomised multicentre trial. Gut. 2009;58:73–78. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.153601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramsoekh D, Haringsma J, Poley JW, van Putten P, van Dekken H, Steyerberg EW, van Leerdam ME, Kuipers EJ. A back-to-back comparison of white light video endoscopy with autofluorescence endoscopy for adenoma detection in high-risk subjects. Gut. 2010;59:785–793. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.151589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rastogi A, Early DS, Gupta N, Bansal A, Singh V, Ansstas M, Jonnalagadda SS, Hovis CE, Gaddam S, Wani SB, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of standard-definition white-light, high-definition white-light, and narrow-band imaging colonoscopy for the detection of colon polyps and prediction of polyp histology. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:593–602. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rex DK, Helbig CC. High yields of small and flat adenomas with high-definition colonoscopes using either white light or narrow band imaging. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:42–47. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rotondano G, Bianco MA, Sansone S, Prisco A, Meucci C, Garofano ML, Cipolletta L. Trimodal endoscopic imaging for the detection and differentiation of colorectal adenomas: A prospective single-centre clinical evaluation. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:331–336. doi: 10.1007/s00384-011-1312-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sabbagh LC, Reveiz L, Aponte D, De Aguiar S. Narrow-band imaging does not improve detection of colorectal polyps when compared to conventional colonoscopy: A randomized controlled trial and meta-analysis of published studies. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:100. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stoffel EM, Turgeon DK, Stockwell DH, Normolle DP, Tuck MK, Marcon NE, Baron JA, Bresalier RS, Arber N, Ruffin MT, et al. Chromoendoscopy detects more adenomas than colonoscopy using intensive inspection without dye spraying. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2008;1:507–513. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Togashi K, Hewett DG, Radford-Smith GL, Francis L, Leggett BA, Appleyard MN. The use of indigocarmine spray increases the colonoscopic detection rate of adenomas. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:826–833. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tribonias G, Theodoropoulou A, Konstantinidis K, Vardas E, Karmiris K, Chroniaris N, Chlouverakis G, Paspatis GA. Comparison of standard vs high-definition, wide-angle colonoscopy for polyp detection: A randomized controlled trial. Colorectal Dis 12 (10 Online) 2010:e260–e266. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van den Broek FJ, Fockens P, Van Eeden S, Kara MA, Hardwick JC, Reitsma JB, Dekker E. Clinical evaluation of endoscopic trimodal imaging for the detection and differentiation of colonic polyps. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:288–295. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park SY, Lee SK, Kim BC, Han J, Kim JH, Cheon JH, Kim TI, Kim WH. Efficacy of chromoendoscopy with indigocarmine for the detection of ascending colon and cecum lesions. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:878–885. doi: 10.1080/00365520801935442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adler A, Aschenbeck J, Yenerim T, Mayr M, Aminalai A, Drossel R, Schröder A, Scheel M, Wiedenmann B, Rösch T. Narrow-band versus white-light high definition television endoscopic imaging for screening colonoscopy: A prospective randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:410–416.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.022. quiz 715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adler A, Pohl H, Papanikolaou IS, Abou-Rebyeh H, Schachschal G, Veltzke-Schlieker W, Khalifa AC, Setka E, Koch M, Wiedenmann B, Rösch T. A prospective randomised study on narrow-band imaging versus conventional colonoscopy for adenoma detection: Does narrow-band imaging induce a learning effect? Gut. 2008;57:59–64. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.123539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ikematsu H, Sakamoto T, Togashi K, Yoshida N, Hisabe T, Kiriyama S, Matsuda K, Hayashi Y, Matsuda T, Osera S, et al. Detectability of colorectal neoplastic lesions using a novel endoscopic system with blue laser imaging: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:386–394. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suzuki T, Hara T, Kitagawa Y, Takashiro H, Nankinzan R, Sugita O, Yamaguchi T. Linked-color imaging improves endoscopic visibility of colorectal nongranular flat lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:692–697. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dos Santos CE, Malaman D, Lopes CV, Pereira-Lima JC, Parada AA. Digital chromoendoscopy for diagnosis of diminutive colorectal lesions. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2012;2012:279521. doi: 10.1155/2012/279521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leung FW. PDR or ADR as a quality indicator for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1000–1002. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lau PC, Sung JJ. Flat adenoma in colon: Two decades of debate. J Dig Dis. 2010;11:201–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2010.00439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ogiso K, Yoshida N, Siah KT, Kitae H, Murakami T, Hirose R, Inada Y, Dohi O, Okayama T, Kamada K, et al. New-generation narrow band imaging improves visibility of polyps: A colonoscopy video evaluation study. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:883–890. doi: 10.1007/s00535-016-1167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The analyzed data sets generated during the study are available in the published article.