Summary

Axonal mitochondrial quality is essential for neuronal health and functions. Compromised mitochondrial quality, reflected by loss of membrane potential, collapse of ATP production, abnormal morphology, burst of reactive oxygen species generation, and impaired Ca2+ buffering capacity, can alter mitochondrial transport. Mitochondrial transport in turn maintains axonal mitochondrial homeostasis in several ways. Newly generated mitochondria are anterogradely transported along with axon from soma to replenish axonal mitochondrial pool, while damaged mitochondria undergo retrograde transport for repair or degradation. Besides, mitochondria are also arrested in axon to quarantine damages locally. Accumulating evidence suggests abnormal mitochondrial transport leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and axon degeneration in a variety of neurological and psychiatric disorders. Further investigations into the details of this process would help to extend our understanding of various neurological diseases and shed light on the corresponding therapies.

Keywords: central nervous system disorders, mitochondrial dynamics, mitochondrial transport, mitophagy

1. INTRODUCTION

The disorders of central nervous system could be devastating due to failures in controlling basic physiological functions and problems with emotional changes and mental tasks. In the past decades, extensive efforts have been made to develop therapies against central nervous system disorders by targeting ion channels and neurotransmitters.1, 2 Besides these achievements, insights gained in recent years have revealed the critical contribution of mitochondria to neuronal health.3 Mitochondria not only serve as the “powerhouse” of neurons but also play essential roles in metabolizing neurotransmitters, buffering Ca2+, and sending signal deciding neuronal survival.4 Mitochondrial quality is therefore the basis of neural homeostasis. Stress‐induced mitochondrial damage results in the collapse of bioenergy generation and even worse, neuronal demise.5, 6 Neurons monitor mitochondrial quality by replenishing mitochondria, repairing damaged mitochondria by fusing with healthy ones, or eliminating mitochondria through autophagic clearance (mitophagy). The dysfunction of mitochondrial quality control has been associated with various neurological disorders.5, 6, 7, 8

Highly polarized morphology distinguishes neurons from other cells. Their long, thin axons are not only unique in morphology but also fundamental to neuronal functions by forming specialized compartments such as synapses and nodes of Ranvier. To meet the ever‐changing demands of neurons, mitochondria have been located in these distal compartments in axons.4 However, it is more challenging for neurons to control the quality of these distal mitochondria due to the limited extent of both mitochondrial biogenesis and degradation in axons.9 To cope with this, neurons develop finely regulated transport system. Specifically, mitochondria newly generated in soma are distributed to axons by anterograde transport, while senescent or damaged mitochondria in axons undergo retrograde transport for repair or autophagic clearance.9 Mitochondria are distributed according to their quality, which is fundamental to neuronal homeostasis and functions.4 The alternation of axonal mitochondrial transport is intimately related to compromised mitochondrial quality and thus contributes to neurological disorders. For example, aberrant protein aggregates and disease‐relevant mutants are prone to compromise axonal mitochondrial trafficking, which further leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal death in a number of neurodegenerative disorders.10, 11, 12 Therefore, correction of disrupted mitochondrial transport seems to be a promising therapy for some neurological disorders. Here, we review the contributions of mitochondrial transport to axonal mitochondrial quality control and its implications for neurological disorders.

2. MITOCHONDRIAL TRANSPORT MACHINERY

Mammalian axons have polarized microtubules with their plus ends oriented toward the terminus and minus ends toward the soma.13 In general, two kinds of motor proteins are responsible for transporting mitochondria in two directions, that is, kinesin family for anterograde transport (away from soma) and dynein‐dynactin complex for retrograde transport (toward soma). In addition, specific mitochondrial anchor protein takes responsibility for mitochondrial docking in axons.

2.1. Anterograde transport motors

Among the kinesin family members, kinesin‐1 (also known as KIF5) serves as the major motor for the anterograde transport of neuronal mitochondria.14 Kinesin heavy chain (KHC) interacts with mitochondria via adaptor proteins, Miro and Milton. Miro is an atypical Rho (Ras homolog) family of GTPases which locates in outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM). Miro interacts with Milton which binds to the C‐terminus of KHC. Mutations in either Miro or Milton disrupt mitochondrial anterograde transport in axons.15, 16 Besides Miro and Milton, syntabulin also adapts KHC to mitochondria.17 In addition, hypoxia‐up‐regulated mitochondrial movement regulator (HUMMR) senses hypoxia and interacts with Miro to regulate mitochondrial mobility.18 Some other kinesin motors, such as kinesin‐3 family proteins KIF1Bα19 and KLP6,20 may also drive anterograde mitochondrial motility.

2.2. Retrograde transport motors

Cytoplasmic dynein drives the mitochondrial retrograde movement in axons. Unlike kinesin family, there is only one identified dynein motor. Dynein is proposed to form a complex with dynactin, and the complicated structure of dynein‐dynactin complex makes it hard to study. Loss of Miro reduces both anterograde and retrograde mitochondrial transport in Drosophila,21 implying the involvement of Miro/Milton in mitochondrial retrograde transport as adaptor proteins. Supportively, dynein‐dynactin complex has been shown to interact with Miro and Milton.22

2.3. Anchor protein

Syntaphilin serves as a mitochondrial anchor protein in axons through its axon‐sorting domain and microtubule‐binding domain.23 In addition, SNPH‐mediated mitochondrial docking is also dependent on kinesin24 and dynein light chain LC8.25 A recent study indicated the recruitment of syntaphilin to mitochondria by optogenetic approach was sufficient to arrest mitochondria transported promptly in both directions. It seems that motor and anchor proteins present on one particular mitochondrion simultaneously and the balance of their forces may decide the direction of mitochondrial movements.26

3. MITOCHONDRIAL QUALITY AND CHANGES OF MITOCHONDRIAL MOVEMENTS

Mitochondrial transport responds to mitochondrial quality and thereby modulates their distribution, which is important to neuronal functions and homeostasis. Compromised mitochondrial quality can be reflected by loss of membrane potential, collapse of ATP production, abnormal mitochondrial morphology, burst of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS), and impaired capacity of Ca2+ buffering. Here, we discussed how impaired mitochondrial quality may impact on mitochondrial trafficking.

3.1. Mitochondrial membrane potential

Stresses or aging can result in the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, which is also defined as mitochondrial depolarization. Under physical conditions, axonal mitochondria with normal membrane potential are transported anterogradely and those with low membrane potential are transported toward the cell body.27 However, mitochondrial uncoupler carbonyl cyanide 3‐chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) induces the phosphorylation and degradation of Miro in a PINK/Parkin‐dependent pathway,28, 29 which further reduces mitochondrial mobility in rat hippocampal axons.28 In addition, as illustrated by a Friedreich ataxia model in Drosophila, depolarized mitochondria with normal mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) production have shown deficits in axonal trafficking, implying mitochondrial depolarization is sufficient to arrest mitochondria.30

3.2. ATP production

Cargo transportation along the axon is an ATP‐consuming process, and more intriguingly, motors for mitochondria seem to be fueled by ATP generated from oxidative phosphorylation rather than glycolysis.31 In cortical neurons from rat brains, inhibition of mitochondrial ATP production by mitochondrial H+‐ATP‐synthase inhibitor oligomycin arrests axonal mitochondrial trafficking while the inhibition of glycolysis shows little impact on mitochondrial mobility.31 These results indicate proper mitochondrial energy generation is the basis for mitochondrial movements in axons and bioenergetic crisis caused by aging or stresses32 may undermine axonal mitochondrial trafficking. On the other hand, axonal mitochondrial mobility changes to fit the neuronal metabolic demands. High extracellular glucose level also decreases axonal mitochondrial mobility by O‐GlcNAcylation of Milton,33 which in turn improves the availability of glucose to mitochondria and thus facilitates bioenergy generation.

3.3. Mitochondrial morphology

Mitochondrial morphology is regulated by several mitochondrial fission and fusion proteins. Dominant negative or depletion of mitochondrial fusion protein mitofusin 2 (Mfn2) causes mitochondrial fragmentation, which coincides with disrupted mitochondrial movement in axons.34 Furthermore, both Mfn1 and Mfn2 interact with Miro and Milton through which they regulate axonal mitochondrial transport.34 Additionally, dynamin‐related protein 1 (Drp1) not only serves as a mitochondrial fission protein but functions with actin‐related protein 10 (Actr10) to promote mitochondrial retrograde transport in axons.35 However, mitochondrial morphology may not be the primary factor to drive mitochondrial trafficking, since the abundance or activity of mitochondrial fission/fusion proteins could be affected by mitochondrial membrane potential loss,36 ATP depletion,37 and mtROS generation.38

3.4. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species

Although mitochondria are the major sites for intracellular ROS generation,39, 40 the association of ROS with axonal mitochondrial transport has been poorly understood. In nonneuronal cells, mitochondria may cause accumulation of nuclear ROS after their retrograde transport during hypoxia.41 The majority of ROS triggered by hypoxia originate from mitochondrial complex III.42 Consistently, mild and prolonged incubation of complex III inhibitor antimycin A promotes axonal mitochondrial retrograde transport in hippocampal neurons.43 In addition, ROS seem to increase the ATPase activity of dynein.44 However, ROS caused by extracellular H2O2 incubation arrest axonal mitochondrial mobility both in vitro45 and in vivo.46 It remains undetermined whether different sources or abundance of ROS exert on mitochondrial trafficking distinctively. Neurons undergoing ischemia may provide a model to address this issue, in which mtROS40 and mitochondrial quality control play critical roles.7, 47, 48, 49

3.5. Mitochondrial calcium buffering

Mitochondria have also been deemed critical for neuronal Ca2+ buffering. Although it is well established that cytosolic Ca2+ is a key regulator of mitochondrial transport, the association of mitochondrial Ca2+ with their movement is still enigmatic. Increased cytosolic Ca2+ arrests mitochondrial trafficking through its binding to Miro1, which dissociates Miro1 from kinesin‐1/Milton/Miro1 complex50 or strips kinesin‐1 from the microtubule.51 It has been reported that WldS, a protein that slows down Wallerian degeneration of axons, exerts its neuroprotection by enhancing mitochondrial trafficking.52 Noteworthy, mitochondria in WldS‐expressing mouse brains show stronger Ca2+ buffering capacity.52 Consistently, axonal mitochondria with lower Ca2+ tend to be mobile and increased Ca2+ in mitochondrial matrix by the activation of mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter arrests mitochondrial transport in axons.53 These results suggest the direct link between axonal mitochondrial mobility and mitochondrial Ca2+; however, the details await further investigations.

4. MITOCHONDRIAL TRANSPORT CONTRIBUTES TO AXONAL MITOCHONDRIAL QUALITY CONTROL

4.1. Anterograde transport for replenishing axonal mitochondria

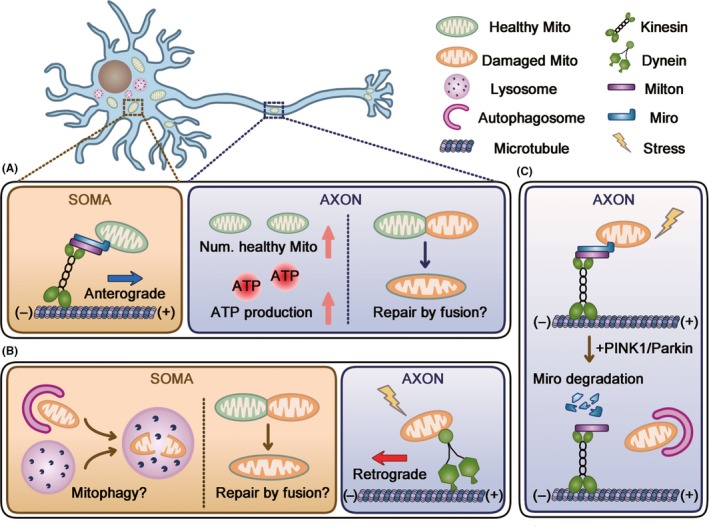

Although mitochondrial biogenesis is shown to occur locally in the axon,54 most new mitochondria are proposed to be generated in the soma.9 Supportively, the study using MitoTimer, a time‐sensitive fluorescent protein located in mitochondrial matrix, has shown that the mitochondrial aging is proportional to the distance from soma.55 Under such circumstances, mitochondrial anterograde transport is indispensable for mitochondrial quality control by providing young mitochondria to distal regions. Accordingly, enhanced mitochondrial transport contributes to energy recovery from injuries and promotes axon regeneration and neuronal survival.56, 57 However, it is still unclear whether improved mitochondrial quality in axons rescues axonal injuries merely by enhancing energy production or alternatively by repairing damaged mitochondria through mitochondrial fusion (Figure 1A). Intriguingly, both mitochondrial fusion and fission proteins could interact with mitochondrial transport system.34, 35 However, the interaction between mitochondrial mobility and dynamics needs to be further addressed.

Figure 1.

Three possible interplays of mitochondrial transport with mitochondrial quality control in axon. Mitochondria are distributed throughout the whole neuron, and neuronal soma is the main compartment where lysosomes residue and mitochondrial biogenesis takes place. Mitochondrial transport could mediate mitochondrial quality control through the following mechanisms: (A) mitochondria generated in soma are anterogradely transported into axon. Improved axonal mitochondrial quality could benefit from increased number of healthy mitochondria or probably mitochondrial fusion between healthy and damaged mitochondria. (B) Damaged mitochondria undergo retrograde transport for mitophagy in soma or fusing with somatic mitochondria. (C) Damaged mitochondrial mobility is arrested by PINK1/Parkin‐dependent degradation of Miro and cleared by local mitophagy in axon

4.2. Retrograde transport for mitochondrial repair or clearance

In addition to the machinery for mitochondrial biogenesis, the degradation organelles, lysosomes, are also predominantly localized in neuronal soma.58, 59 Thus, it has been speculated that damaged mitochondria in axons return to cell bodies for degradation. Indeed, most mitochondria with low membrane potential are retrogradely transported in intact axons.27 Similarly, mitochondria move retrogradely and escape from axons after mild and chronic stress in cultured hippocampal neurons.43 In addition, soma‐restricted mitophagy has been shown in both in vitro60 and in vivo.61 These results indicate that mitochondrial retrograde transport may serve as an axonal mitochondrial quality control strategy by removing damaged mitochondria from axons. However, these studies did not address the final outcome of those mobile mitochondria (being repaired by fusing with somatic mitochondria or being cleared in soma; Figure 1B). Thus, the direct evidence showing axonal mitochondria return to soma for repair or clearance is still lacking.

4.3. Arresting mitochondrial mobility to quarantine damages

Accumulating evidence indicates the previously underestimated close association of mitochondrial mobility with mitophagy in axon. PINK1/Parkin, the most extensively studied mitophagy pathway, is found to degrade Miro upon mitochondrial depolarization, which arrests mitochondrial movements.28 A more recent study showed that axonal mitochondria were cleared in situ by PINK1/Parkin‐mediated mitophagy.62 These observations proposed that the mitochondrial arrest‐and‐mitophagy manner quarantines mitochondrial damages spatially from further affecting the overall mitochondria pool (Figure 1C). However, axonal mitophagy has not been verified in disease‐relevant models and there is a paucity of direct evidence proving the significance of mitochondrial arrest to axonal health. Additionally, Parkin deficiency reduces axonal mitochondrial content in Drosophila.61 This result is in contrast to the predicted local mitophagy in axons62 and implies that soma could be the main compartment for mitophagy in neuron. Further investigations are needed to explore the factors in deciding the intracellular sites where axonal mitochondria degradation occurs. It is possible that mitochondrial transport responds to different stresses and disposes axonal mitochondria in distinct ways.

5. IMPLICATIONS OF AXONAL MITOCHONDRIAL TRANSPORT FOR NEUROLOGICAL DISORDERS

5.1. Neurodegeneration

Neurodegeneration is characterized by the progressive loss of structure or functions of certain neuronal subtypes, which further leads to functional impairments. Although in the face of increasing clinical demand, there have been few effective therapies for neurodegenerative disorders due to the limited insight into their mechanisms. In recent years, the role of mitochondria in the neurodegeneration has begun to come to prominence.63 Here, we focus on the association of mitochondrial transport with neurodegeneration.

5.1.1. Alzheimer's disease (AD)

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most prevalent form of dementia worldwide. AD is characterized by progressive death of specific neuronal populations64; however, mounting evidence indicates axon degeneration long precedes somatic cell death.65, 66 One feature of axon pathology in AD is the impaired axonal transport, including axonal mitochondrial transport defects.67, 68

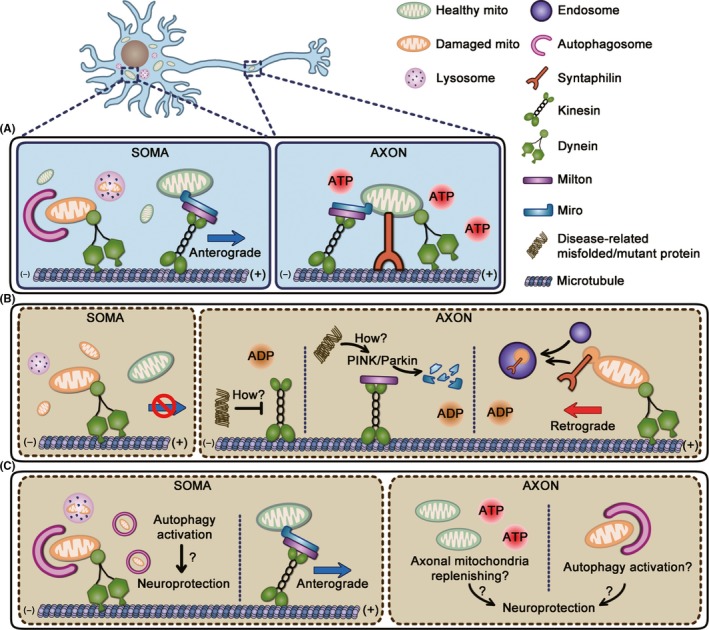

Extracellular plaques composed of amyloid‐β (Aβ) peptides and intracellular fibrillar tau aggregates are two major histopathological hallmarks of AD. Both Aβ and tau have been shown to disrupt axonal mitochondrial transport. Incubation of cultured hippocampal neurons with Aβ reduces mitochondrial mobility.10, 69 Unlike Aβ, the impact of tau on axonal transport is still inconclusive under physiological conditions.69, 70 Tau overexpression in differentiated N2a cells has been shown to arrest axonal mitochondrial trafficking.71 However, the inhibitory effect of Aβ on axonal mitochondrial movements is counteracted by tau ablation in cultured hippocampal neurons, indicating a more critical role of tau in mitochondrial trafficking under pathological conditions.69 Intriguingly, mitochondrial anterograde transport seems to be more vulnerable in AD.69, 71, 72 One possible mechanism underlying the more obvious loss of mitochondrial anterograde transport is that tau inhibits kinesin‐1 activity but has little effect on dynein‐based movement.71, 73, 74 In addition to mitochondrial anterograde motors, mitochondrial anchor protein syntaphilin buds out of axonal mitochondria and is further degraded in AD‐related mutant hAPP Tg neurons, which increases mitochondrial retrograde movements in axons (Figure 2A,B).43 Furthermore, mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) blockage by genetic depletion of cyclophilin D, one of the structural components of mPTP, attenuates impaired mitochondrial trafficking induced by Aβ and this protective effect is related to the reduced Ca2+ and ROS.75 These results imply that defective mitochondrial transport in AD may also result from the release of mitochondrial Ca2+ and ROS.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of involvements of mitochondrial transport in neurodegeneration diseases. A, In intact neurons, mitochondrial transport system properly distributes mitochondria which satisfy energy demands of axons. Besides, damaged axonal mitochondria undergo autophagic clearance successfully in soma after retrograde transport. B, Mitochondrial transport is impaired in neurodegeneration diseases. Neurodegeneration‐related misfolded or mutant proteins can inhibit kinesin‐1 activity71, 73, 74, 103 and induce degradation of Miro1 in a Parkin‐dependent manner.89 The detailed mechanisms underlying the inhibition of mitochondrial anterograde transport in neurodegeneration need further investigations. Additionally, mitochondrial anchor protein syntaphilin buds out of axonal mitochondria and is further degraded in early stages of AD and fALS, which increased mitochondrial retrograde movements in axons.43 However, damaged mitochondria accumulate after returning back to soma due to autophagy defects and a lack of mitochondrial anterograde transport in a long run causes axonal energy depletion. C, The combination of corrected mitochondrial trafficking with autophagy activation might confer neuroprotection by degrading both somatic and axonal damaged mitochondria and ameliorating energy stress in axons simultaneously

The defects of anterograde motor's function together with loss of mitochondrial anchor protein lead to the increase of axonal mitochondrial retrograde transport in AD‐relevant models, which may serve as a first‐line strategy to remove defective mitochondria in axons. However, axonal mitochondria cannot be replenished due to a lack of mitochondrial anterograde transport in a long run. Consistently, reduced mitochondrial content in neurites has been reported in models both in vivo76 and in vitro.71 Given the critical role of mitochondria in energy production and synaptic Ca2+ buffering, impaired axonal mitochondrial transport may lead to synaptic dysfunction and axon degeneration. Furthermore, accumulated mitochondria in soma could not be cleared as a result of autophagy defects (Figure 2A,B),77, 78 which would further aggravate neuronal death in AD.

5.1.2. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), which is caused by the selective loss of motor neurons in the spinal cord, motor cortex, and brain stem, is the most frequent adult‐onset motor neuron disease.79 Approximately 10% of ALS is inherited (familiar ALS, fALS), and several genes have been reported to be related to fALS, including superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), TAR DNA‐binding protein (TARDBP; TDP‐43), fused in sarcoma (FUS), vesicle‐associated membrane protein–associated protein B (VAPB), and C9orf72.80 Although most ALS cases are sporadic without clear genetic consequences, mitochondrial defects and impaired axonal transport have been shown to be intimately linked with motor neuron degeneration.81, 82

In fALS‐related animal models or cultured neurons, the alteration of axonal mitochondrial transport is inconsistent with distinct gene mutations. Similar to AD, selective anterograde defect has been reported in cultured cortical neurons expressing ALS mutant SOD1G93A, SOD1A4V, SOD1G85R, SOD1G37R, or VAPBP56S and in embryonic motor neurons expressing SOD1G93A.12, 83 The intact sciatic nerve of presymptomatic SOD1G93A transgenic mice also exhibits reduced anterograde transport of mitochondria.84, 85 However, wild‐type TDP‐43 and ALS‐related mutants TDP‐43Q331K, A315T, or M337V lead to decreased mitochondrial mobility in both anterograde and retrograde directions.85, 86 In addition, the roles of FUS, C9orf72, and their mutants in mitochondrial transport are still conflicting.87, 88

The molecular mechanisms underlying defective mitochondrial transport remain unsolved. It was reported that ALS mutant SOD1 induced degradation of Miro1 in a Parkin‐dependent manner, which further inhibited anterograde axonal transport of mitochondria.89 The degradation of syntaphilin also contributes to the alteration of mitochondrial mobility in the early stages of fALS‐linked mice (Figure 2A,B).43 However, given the roles of Miro and syntaphilin in both anterograde and retrograde mitochondrial transport, further investigations are needed to address the selective defects of mitochondrial anterograde transport in some fALS models.

Lack of mitochondrial anterograde transport may result in the loss of mitochondrial content in neurites which has been verified in several fALS models.12, 90 Thus, increasing mitochondrial mobility might help to replenish axonal mitochondria or to send damaged mitochondria for mitophagy in soma. However, enhanced axonal motility by depletion of syntaphilin fails to slow the disease progression in hSOD1G93A mice.91 Instead, improved autophagy‐lysosomal functions by enhancing transport of late endosomes ameliorate ALS‐like phenotype.92 Given the mitochondrial dysfunction and autophagy defects in ALS,93, 94 it may be necessary to combine strategies correcting mitochondrial transport with drugs activating autophagy to improve the mitochondrial quality in ALS (Figure 2C).

5.1.3. Huntington's disease (HD)

Huntington's disease (HD) is an autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder caused by the pathogenic expansion of the CAG tract beyond 35 repeats at the N‐terminus of the huntingtin (Htt) protein.95 Htt interacts with both anterograde and retrograde transport motor proteins.96, 97 For certain cargoes, the phosphorylation state of Htt plays a role in deciding the directions of their axonal transport.99

Recent studies have indicated that impaired mitochondrial transport involves in the pathology of HD. Mutant of Htt (mHtt) impairs mitochondrial trafficking in both directions in neurons.100, 101 Noteworthy, in striatal neurons, mitochondrial transport impairment occurs before mHtt aggregates formation102 while mitochondria become immobile adjacent to aggregates in cortical neurons,101 suggesting the vulnerability of striatal neurons to mHtt toxicity compare with other neuronal subtypes.

The mechanism by which mHtt inhibits mitochondrial transport is not fully understood. Soluble N‐terminal mHtt interacted with mitochondria, which interferes with the association of microtubule‐based transport motors with mitochondria.102 Alternatively, mHtt could sequester motor proteins into aggregates and abolish axonal mitochondrial trafficking in neurons.103

5.1.4. Parkinson's disease (PD)

Parkinson's disease (PD) is characterized by the selective loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and intracellular inclusions containing aggregates of α‐synuclein.104 Although mitochondrial dysfunction is generally accepted underlying PD pathogenesis, the alteration of mitochondrial transport in PD neurons is still inconclusive. Besides the aforementioned studies on Parkin or PINK1, two PD‐linked proteins, some other evidence emphasizes the involvement of mitochondrial transport in PD pathology. 6‐OHDA and MPP+, two toxins causing dopaminergic neuron death, disrupt axonal mitochondrial transport in cultured neurons, and this inhibitory effect on mitochondrial transport can be reversed by antioxidants,105, 106 indicating ROS may be one of the consequences of mitochondrial arrest in PD‐related models.

5.2. Neuropsychiatric disorders

Mitochondrial dysfunctions and mitochondrial motility defects have also been associated with several psychiatric disorders.

Although mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation system (OXPHOS) deficits, especially complex I deficit, contribute to schizophrenia,107 direct evidence for altered mitochondrial trafficking in schizophrenia has been lacking. Disrupted in schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) is a genetic risk factor for schizophrenia.108 DISC1 interacts with TRAK1 and Miro1 to regulate anterograde transport of mitochondria, which is impaired by a rare DISC1 sequence variant.109 In addition, NDE1 and GSK3β, two interactors of DISC1, also function with TRAK1 to regulate axonal mitochondrial motility.110 DISC1 may also collaborate with syntaphilin to anchor mitochondria in axons.111 In neuronal stress, DISC1 dysfunction impairs mitochondrial functions.112 However, it remains unclear whether DISC1‐related mitochondrial trafficking plays a role in mitochondrial dysfunction in schizophrenia.

The cannabinoid CB1 receptor may play a critical role in the pathology of various neuropsychiatric disorders including alcoholism, depression, anxiety, and schizophrenia.113 Interestingly, CB1 receptor localizes to mitochondria where its activation inhibits mitochondrial respiration and mobility, which contributes to acute cannabinoid‐induced memory impairment.114

Depression was found to be associated with impaired mitochondrial quality indicated by increased production of mtROS.115 Depression can be attributed to a loss of serotonin which increases mitochondrial motility in cultured hippocampal neurons.116 More intriguingly, dopamine, another depression‐related neurotransmitter, seems to exert different impacts on mitochondrial trafficking through multiple dopamine receptors.117

Current evidence has implied the involvement of both mitochondrial dysfunctions and transport alternations in neuropsychiatric disorders. However, it remains enigmatic how mitochondrial dysregulations may contribute to these diseases. Since the neurotransmitter receptors are promising therapeutic targets for not only psychiatric disorders but also other neurological diseases,118, 119 their impacts on axonal mitochondrial quality and mobility need to be addressed in details. Further researches in this field will extend our knowledge about the pathology of psychiatric disorders and open a way to develop novel therapies.

5.3. Traumatic axonal injury

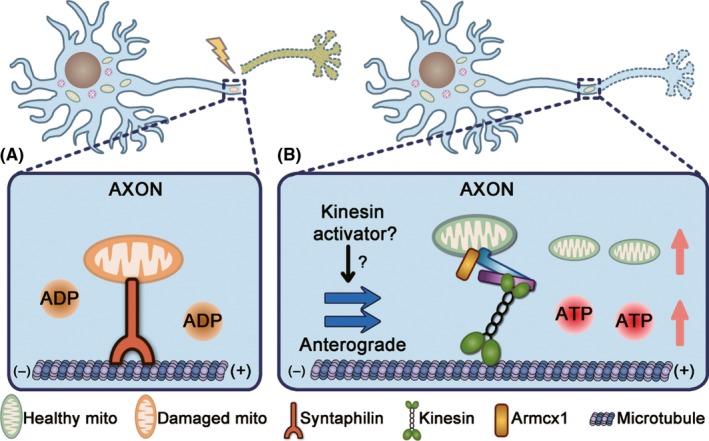

An estimated 50 million people will experience traumatic brain injury (TBI) every year, which has become a global health concern.120 Traumatic axonal injury (TAI), as an important pathoanatomical subtype of TBI, is a major cause of mortality and functional impairment.121 Lines of evidence suggest that mitochondrial transport plays a critical role in TAI by using axotomy. Axotomy causes acute mitochondrial membrane potential loss and ATP depletion in injured axons of mature neurons in which syntaphilin expression is higher and axonal mitochondria are less mobile56 (Figure 3A). Increased mitochondrial transport by either Miro1 overexpression or syntaphilin knockout promotes axonal regeneration by replenishing healthy mitochondria and thus rescuing energy deficits in injured axons56 (Figure 3B). Additionally, dual‐leucine zipper kinase‐1 (DLK‐1), a regulator of axon regeneration, elevates axonal mitochondrial density in a Miro‐independent manner, and increased axonal mitochondria are required for axon regeneration after axotomy.122 Armadillo repeat–containing, X‐linked 1 (Armcx1) could interact with Miro1 and enhance mitochondrial transport in adult retinal ganglion cells (RGCs).57 Armcx1 overexpression promotes mitochondrial transport and neurite outgrowth in cortical neurons (Figure 3B) and, more importantly, promotes neuronal survival and axon regeneration after optic nerve injury in vivo.57 Taken together, mitochondrial transport resolves bioenergetic crisis in injured axons by replenishing axonal mitochondria, suggesting that modulating mitochondrial transport might provide a novel strategy to axonal regeneration in TAI.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of neuroprotection of mitochondrial anterograde transport against TAI. A, TAI causes mitochondrial damages and ATP depletion in injured axons of mature neurons in which syntaphilin expression is higher and mitochondrial mobility is limited. B, Increased mitochondrial anterograde transport by syntaphilin knockout56 or overexpression of Miro1,56, 122 DLK‐1,122 or Armcx157 replenishes axonal mitochondria and rescues energy collapse in injured axons, which further promotes axon regeneration. It is worth further investigations to treat TAI by enhancing mitochondrial anterograde transport with kinesin activators

6. PERSPECTIVE

Mitochondrial transport is critical to maintain the healthy state of mitochondrial population in axons and play an important role in various neurological and psychiatric disorders. However, many issues in this field need to be addressed. It is unknown how motor and anchor proteins sense mitochondrial quality and make corresponding respond. Besides, the intracellular sites where axonal mitochondria undergo mitophagy await to be untangled. It is also worthwhile to investigate how mitochondrial transport coordinates with other mitochondrial quality control strategies, such as mitophagy and mitochondrial fusion/fission. Fortunately, emerging technologies, such as optogenetics,26, 123 have implemented more precise control of mitochondrial quality and mitochondrial motor or anchor proteins, which will help to extend our understanding of how mitochondrial transport involves in mitochondrial quality control in axon. Although the defects of axonal mitochondrial trafficking have been implicated in various neurological disorders, limited efforts have been made to rescue impaired mitochondrial transport in disease‐relevant models. In addition, mitochondrial transport must work in tandem with other mitochondrial quality control strategies to maintain axonal mitochondrial homeostasis. Thus, the combination of corrected mitochondrial trafficking with enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis or mitophagy (Figure 2C) may be indispensable for the treatment of neurological disorders. On the other hand, mitochondrial trafficking may serve as a novel readout in screening potential compounds for neurological disorders. In particular, mitochondrial anterograde transport seems to be a promising therapeutic target for TAI and the activator of kinesin‐1 has been available (Figure 3B).124 Taken together, pioneer investigations are needed to explore the translational implications of axonal mitochondrial transport in central nervous system disorders.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81630098, 81573406 and 81822044).

Zheng Y‐R, Zhang X‐N, Chen Z. Mitochondrial transport serves as a mitochondrial quality control strategy in axons: Implications for central nervous system disorders. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2019;25:876–886. 10.1111/cns.13122

REFERENCES

- 1. Ng J, Papandreou A, Heales SJ, Kurian MA. Monoamine neurotransmitter disorders–clinical advances and future perspectives. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(10):567‐584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kumar P, Kumar D, Jha SK, Jha NK, Ambasta RK. Ion channels in neurological disorders. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2016;103:97‐136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Devine MJ, Kittler JT. Mitochondria at the neuronal presynapse in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018;19(2):63‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Course MM, Wang X. Transporting mitochondria in neurons. F1000Res. 2016;5(F1000 Faculty Rev):1735. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yuan Y, Zhang X, Zheng Y, Chen Z. Regulation of mitophagy in ischemic brain injury. Neurosci Bull. 2015;31(4):395‐406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Golpich M, Amini E, Mohamed Z, Azman Ali R, Mohamed Ibrahim N, Ahmadiani A. Mitochondrial dysfunction and biogenesis in neurodegenerative diseases: pathogenesis and treatment. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2017;23(1):5‐22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang X, Yan H, Yuan Y, et al. Cerebral ischemia‐reperfusion‐induced autophagy protects against neuronal injury by mitochondrial clearance. Autophagy. 2013;9(9):1321‐1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Youle RJ, van der Bliek AM. Mitochondrial fission, fusion, and stress. Science. 2012;337(6098):1062‐1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sheng ZH, Cai Q. Mitochondrial transport in neurons: impact on synaptic homeostasis and neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(2):77‐93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rui YF, Tiwari P, Xie ZP, Zheng JQ. Acute impairment of mitochondrial trafficking by beta‐amyloid peptides in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26(41):10480‐10487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chang D, Rintoula GL, Pandipati S, Reynolds IJ. Mutant huntingtin aggregates impair mitochondrial movement and trafficking in cortical neurons. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;22(2):388‐400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. De Vos KJ, Chapman AL, Tennant ME, et al. Familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis‐linked SOD1 mutants perturb fast axonal transport to reduce axonal mitochondria content. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16(22):2720‐2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baas PW, Deitch JS, Black MM, Banker GA. Polarity orientation of microtubules in hippocampal neurons: uniformity in the axon and nonuniformity in the dendrite. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85(21):8335‐8339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pilling AD, Horiuchi D, Lively CM, Saxton WM. Kinesin‐1 and Dynein are the primary motors for fast transport of mitochondria in Drosophila motor axons. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(4):2057‐2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stowers RS, Megeath LJ, Gorska‐Andrzejak J, Meinertzhagen IA, Schwarz TL. Axonal transport of mitochondria to synapses depends on milton, a novel Drosophila protein. Neuron. 2002;36(6):1063‐1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guo XF, Macleod GT, Wellington A, et al. The GTPase dMiro is required for axonal transport of mitochondria to Drosophila synapses. Neuron. 2005;47(3):379‐393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cai Q, Gerwin C, Sheng ZH. Syntabulin‐mediated anterograde transport of mitochondria along neuronal processes. J Cell Biol. 2005;170(6):959‐969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li Y, Lim S, Hoffman D, Aspenstrom P, Federoff HJ, Rempe DA. HUMMR, a hypoxia‐ and HIF‐1alpha‐inducible protein, alters mitochondrial distribution and transport. J Cell Biol. 2009;185(6):1065‐1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nangaku M, Sato‐Yoshitake R, Okada Y, et al. KIF1B, a novel microtubule plus end‐directed monomeric motor protein for transport of mitochondria. Cell. 1994;79(7):1209‐1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tanaka K, Sugiura Y, Ichishita R, Mihara K, Oka T. KLP6: a newly identified kinesin that regulates the morphology and transport of mitochondria in neuronal cells. J Cell Sci. 2011;124(14):2457‐2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Russo GJ, Louie K, Wellington A, et al. Drosophila miro is required for both anterograde and retrograde axonal mitochondrial transport. J Neurosci. 2009;29(17):5443‐5455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van Spronsen M, Mikhaylova M, Lipka J, et al. TRAK/Milton motor‐adaptor proteins steer mitochondrial trafficking to axons and dendrites. Neuron. 2013;77(3):485‐502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kang JS, Tian JH, Pan PY, et al. Docking of axonal mitochondria by syntaphilin controls their mobility and affects short‐term facilitation. Cell. 2008;132(1):137‐148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen Y, Sheng ZH. Kinesin‐1‐syntaphilin coupling mediates activity‐dependent regulation of axonal mitochondrial transport. J Cell Biol. 2013;202(2):351‐364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen YM, Gerwin C, Sheng ZH. Dynein light chain LC8 regulates syntaphilin‐mediated mitochondrial docking in axons. J Neurosci. 2009;29(30):9429‐9438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van Bergeijk P, Adrian M, Hoogenraad CC, Kapitein LC. Optogenetic control of organelle transport and positioning. Nature. 2015;518(7537):111‐114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miller KE, Sheetz MP. Axonal mitochondrial transport and potential are correlated. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 13):2791‐2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang X, Winter D, Ashrafi G, et al. PINK1 and Parkin target Miro for phosphorylation and degradation to arrest mitochondrial motility. Cell. 2011;147(4):893‐906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shlevkov E, Kramer T, Schapansky J, LaVoie MJ, Schwarz TL. Miro phosphorylation sites regulate Parkin recruitment and mitochondrial motility. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(41):E6097‐E6106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shidara Y, Hollenbeck PJ. Defects in mitochondrial axonal transport and membrane potential without increased reactive oxygen species production in a Drosophila model of Friedreich ataxia. J Neurosci. 2010;30(34):11369‐11378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zala D, Hinckelmann MV, Yu H, et al. Vesicular glycolysis provides on‐board energy for fast axonal transport. Cell. 2013;152(3):479‐491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Atamna H. Heme, iron, and the mitochondrial decay of ageing. Ageing Res Rev. 2004;3(3):303‐318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pekkurnaz G, Trinidad JC, Wang X, Kong D, Schwarz TL. Glucose regulates mitochondrial motility via Milton modification by O‐GlcNAc transferase. Cell. 2014;158(1):54‐68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Misko A, Jiang SR, Wegorzewska I, Milbrandt J, Baloh RH. Mitofusin 2 is necessary for transport of axonal mitochondria and interacts with the miro/milton complex. J Neurosci. 2010;30(12):4232‐4240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Drerup CM, Herbert AL, Monk KR. Nechiporuk AV. Regulation of mitochondria‐dynactin interaction and mitochondrial retrograde transport in axons. Elife. 2017;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36. Chen Y, Dorn GW 2nd. PINK1‐phosphorylated mitofusin 2 is a Parkin receptor for culling damaged mitochondria. Science. 2013;340(6131):471‐475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. De Vos KJ, Allan VJ, Grierson AJ, Sheetz MP. Mitochondrial function and actin regulate dynamin‐related protein 1‐dependent mitochondrial fission. Curr Biol. 2005;15(7):678‐683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wu S, Zhou F, Zhang Z, Xing D. Mitochondrial oxidative stress causes mitochondrial fragmentation via differential modulation of mitochondrial fission‐fusion proteins. FEBS J. 2011;278(6):941‐954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Turrens JF. Superoxide production by the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Biosci Rep. 1997;17(1):3‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chouchani ET, Pell VR, Gaude E, et al. Ischaemic accumulation of succinate controls reperfusion injury through mitochondrial ROS. Nature. 2014;515(7527):431–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Al‐Mehdi AB, Pastukh VM, Swiger BM, et al. Perinuclear mitochondrial clustering creates an oxidant‐rich nuclear domain required for hypoxia‐induced transcription. Sci Signal. 2012;5(231):ra47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Guzy RD, Hoyos B, Robin E, et al. Mitochondrial complex III is required for hypoxia‐induced ROS production and cellular oxygen sensing. Cell Metab. 2005;1(6):401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lin MY, Cheng XT, Tammineni P, et al. Releasing syntaphilin removes stressed mitochondria from axons independent of mitophagy under pathophysiological conditions. Neuron. 2017;94(3):595–610 e596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Xu M, Li XX, Chen Y, Pitzer AL, Zhang Y, Li PL. Enhancement of dynein‐mediated autophagosome trafficking and autophagy maturation by ROS in mouse coronary arterial myocytes. J Cell Mol Med. 2014;18(11):2165–2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Debattisti V, Gerencser AA, Saotome M, Das S, Hajnoczky G. ROS control mitochondrial motility through p38 and the motor adaptor Miro/Trak. Cell Rep. 2017;21(6):1667–1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Liao PC, Tandarich LC, Hollenbeck PJ. ROS regulation of axonal mitochondrial transport is mediated by Ca2+ and JNK in Drosophila. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0178105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang X, Yuan Y, Jiang L, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induced by tunicamycin and thapsigargin protects against transient ischemic brain injury: Involvement of PARK2‐dependent mitophagy. Autophagy. 2014;10(10):1801–1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shen Z, Zheng Y, Wu J, et al. PARK2‐dependent mitophagy induced by acidic postconditioning protects against focal cerebral ischemia and extends the reperfusion window. Autophagy. 2017;13(3):473–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yuan Y, Zheng Y, Zhang X, et al. BNIP3L/NIX‐mediated mitophagy protects against ischemic brain injury independent of PARK2. Autophagy. 2017;13(10):1754–1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. MacAskill AF, Rinholm JE, Twelvetrees AE, et al. Miro1 is a calcium sensor for glutamate receptor‐dependent localization of mitochondria at synapses. Neuron. 2009;61(4):541–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang X, Schwarz TL. The mechanism of Ca2+ ‐dependent regulation of kinesin‐mediated mitochondrial motility. Cell. 2009;136(1):163–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Avery MA, Rooney TM, Pandya JD, et al. Wld(S) prevents axon degeneration through increased mitochondrial flux and enhanced mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering. Curr Biol. 2012;22(7):596–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chang KT, Niescier RF, Min KT. Mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ as an intrinsic signal regulating mitochondrial motility in axons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(37):15456–15461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Amiri M, Hollenbeck PJ. Mitochondrial biogenesis in the axons of vertebrate peripheral neurons. Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68(11):1348–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ferree AW, Trudeau K, Zik E, et al. MitoTimer probe reveals the impact of autophagy, fusion, and motility on subcellular distribution of young and old mitochondrial protein and on relative mitochondrial protein age. Autophagy. 2013;9(11):1887–1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhou B, Yu P, Lin MY, Sun T, Chen Y, Sheng ZH. Facilitation of axon regeneration by enhancing mitochondrial transport and rescuing energy deficits. J Cell Biol. 2016;214:103‐119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cartoni R, Norsworthy MW, Bei F, et al. The mammalian‐specific protein Armcx1 regulates mitochondrial transport during axon regeneration. Neuron. 2017;94(3):689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Parton RG, Simons K, Dotti CG. Axonal and dendritic endocytic pathways in cultured neurons. J Cell Biol. 1992;119(1):123–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Farias GG, Guardia CM, De Pace R, Britt DJ, Bonifacino JS. BORC/kinesin‐1 ensemble drives polarized transport of lysosomes into the axon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(14):E2955–E2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Cai Q, Zakaria HM, Simone A, Sheng ZH. Spatial parkin translocation and degradation of damaged mitochondria via mitophagy in live cortical neurons. Curr Biol. 2012;22(6):545–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sung H, Tandarich LC, Nguyen K, Hollenbeck PJ. Compartmentalized regulation of Parkin‐mediated mitochondrial quality control in the Drosophila nervous system in vivo. J Neurosci. 2016;36(28):7375–7391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ashrafi G, Schlehe JS, LaVoie MJ, Schwarz TL. Mitophagy of damaged mitochondria occurs locally in distal neuronal axons and requires PINK1 and Parkin. J Cell Biol. 2014;206(5):655–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Schon EA, Przedborski S. Mitochondria: the next (neurode)generation. Neuron. 2011;70(6):1033–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Goate AM. Alzheimer's disease: the challenge of the second century. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(77):77sr71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kneynsberg A, Combs B, Christensen K, Morfini G, Kanaan NM. Axonal degeneration in tauopathies: disease relevance and underlying mechanisms. Front Neurosci. 2017;11:572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Salvadores N, Sanhueza M, Manque P, Court FA. Axonal degeneration during aging and its functional role in neurodegenerative disorders. Front Neurosci. 2017;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kandan NM, Pigino GF, Brady ST, Lazarov O, Binder LI, Morfini GA. Axonal degeneration in Alzheimer's disease: when signaling abnormalities meet the axonal transport system. Exp Neurol. 2013;246:44–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Vicario‐Orri E, Opazo CM, Munoz FJ. The pathophysiology of axonal transport in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43(4):1097–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Vossel KA, Zhang K, Brodbeck J, et al. Tau reduction prevents a beta‐induced defects in axonal transport. Science. 2010;330(6001):198–U152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Yuan A, Kumar A, Peterhoff C, Duff K, Nixon RA. Axonal transport rates in vivo are unaffected by tau deletion or overexpression in mice. J Neurosci. 2008;28(7):1682–1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ebneth A, Godemann R, Stamer K, et al. Overexpression of tau protein inhibits kinesin‐dependent trafficking of vesicles, mitochondria, and endoplasmic reticulum: implications for Alzheimer's disease. J Cell Biol. 1998;143(3):777–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Calkins MJ, Reddy PH. Amyloid beta impairs mitochondrial anterograde transport and degenerates synapses in Alzheimer's disease neurons. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2011;1812(4):507–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Seitz A, Kojima H, Oiwa K, Mandelkow EM, Song YH, Mandelkow E. Single‐molecule investigation of the interference between kinesin, tau and MAP2c. EMBO J. 2002;21(18):4896–4905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Stern JL, Lessard DV, Hoeprich GJ, Morfini GA, Berger CL. Phosphoregulation of Tau modulates inhibition of kinesin‐1 motility. Mol Biol Cell. 2017;28(8):1079–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Guo L, Du H, Yan S, et al. Cyclophilin D deficiency rescues axonal mitochondrial transport in Alzheimer's neurons. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Iijima‐Ando K, Hearn SA, Shenton C, Gatt A, Zhao L, Iijima K. Mitochondrial mislocalization underlies Abeta42‐induced neuronal dysfunction in a Drosophila model of Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One. 2009;4(12):e8310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Schneider JL, Cuervo AM. Autophagy and human disease: emerging themes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2014;26:16–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Tammineni P, Ye X, Feng T, Aikal D, Cai Q. Impaired retrograde transport of axonal autophagosomes contributes to autophagic stress in Alzheimer's disease neurons. eLife. 2017;6:e21776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Braak H, Brettschneider J, Ludolph AC, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Del Tredici K. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis‐a model of corticofugal axonal spread. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9(12):708–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Renton AE, Chio A, Traynor BJ. State of play in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genetics. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(1):17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Rossi S, Cozzolino M, Carri MT. Old versus new mechanisms in the pathogenesis of ALS. Brain Pathol. 2016;26(2):276–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Boillee S, Vande Velde C, Cleveland DW. ALS: a disease of motor neurons and their nonneuronal neighbors. Neuron. 2006;52(1):39–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Morotz GM, De Vos KJ, Vagnoni A, Ackerley S, Shaw CE, Miller CC. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis‐associated mutant VAPBP56S perturbs calcium homeostasis to disrupt axonal transport of mitochondria. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(9):1979–1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Bilsland LG, Sahai E, Kelly G, Golding M, Greensmith L, Schiavo G. Deficits in axonal transport precede ALS symptoms in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(47):20523–20528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Magrane J, Cortez C, Gan WB, Manfredi G. Abnormal mitochondrial transport and morphology are common pathological denominators in SOD1 and TDP43 ALS mouse models. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(6):1413–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Wang W, Wang L, Lu J, et al. The inhibition of TDP‐43 mitochondrial localization blocks its neuronal toxicity. Nat Med. 2016;22(8):869–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Chen Y, Deng J, Wang P, et al. PINK1 and Parkin are genetic modifiers for FUS‐induced neurodegeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25(23):5059–5068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Baldwin KR, Godena VK, Hewitt VL, Whitworth AJ. Axonal transport defects are a common phenotype in Drosophila models of ALS. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25(12):2378–2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Moller A, Bauer CS, Cohen RN, Webster CP, De Vos KJ. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis‐associated mutant SOD1 inhibits anterograde axonal transport of mitochondria by reducing Miro1 levels. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26(23):4668–4679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Vande Velde C, McDonald KK, Boukhedimi Y, et al. Misfolded SOD1 associated with motor neuron mitochondria alters mitochondrial shape and distribution prior to clinical onset. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e22031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Zhu YB, Sheng ZH. Increased axonal mitochondrial mobility does not slow amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)‐like disease in mutant SOD1 mice. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(26):23432–23440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Xie YX, Zhou B, Lin MY, Wang SW, Foust KD, Sheng ZH. Endolysosomal deficits augment mitochondria pathology in spinal motor neurons of asymptomatic fALS mice. Neuron. 2015;87(2):355–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Murphy MP, Hartley RC. Mitochondria as a therapeutic target for common pathologies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:865‐886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Nixon RA. The role of autophagy in neurodegenerative disease. Nat Med. 2013;19(8):983–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Caron NS, Dorsey ER, Hayden MR. Therapeutic approaches to Huntington disease: from the bench to the clinic. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17(10):729–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. McGuire JR, Rong J, Li SH, Li XJ. Interaction of huntingtin‐associated protein‐1 with kinesin light chain – implications in intracellular trafficking in neurons. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(6):3552–3559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Engelender S, Sharp AH, Colomer V, et al. Huntingtin‐associated protein 1 (HAP1) interacts with the p150Glued subunit of dynactin. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6(13):2205–2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Caviston JP, Ross JL, Antony SM, Tokito M, Holzbaur E. Huntingtin facilitates dynein/dynactin‐mediated vesicle transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(24):10045–10050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Colin E, Zala D, Liot G, et al. Huntingtin phosphorylation acts as a molecular switch for anterograde/retrograde transport in neurons. EMBO J. 2008;27(15):2124–2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Song W, Chen J, Petrilli A, et al. Mutant huntingtin binds the mitochondrial fission GTPase dynamin‐related protein‐1 and increases its enzymatic activity. Nat Med. 2011;17(3):377–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Chang DT, Rintoul GL, Pandipati S, Reynolds IJ. Mutant huntingtin aggregates impair mitochondrial movement and trafficking in cortical neurons. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;22(2):388–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Orr AL, Li S, Wang C‐E, et al. N‐terminal mutant huntingtin associates with mitochondria and impairs mitochondrial trafficking. J Neurosci. 2008;28(11):2783–2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Trushina E, Dyer RB, Badger JD, et al. Mutant huntingtin impairs axonal trafficking in mammalian neurons in vivo and in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(18):8195–8209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Poewe W, Seppi K, Tanner CM, et al. Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Lu X, Kim‐Han JS, Harmon S, Sakiyama‐Elbert SE, O'Malley KL. The Parkinsonian mimetic, 6‐OHDA, impairs axonal transport in dopaminergic axons. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Kim‐Han JS, Antenor‐Dorsey JA, O'Malley KL. The parkinsonian mimetic, MPP+, specifically impairs mitochondrial transport in dopamine axons. J Neurosci. 2011;31(19):7212–7221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Ben‐Shachar D. Mitochondrial multifaceted dysfunction in schizophrenia; complex I as a possible pathological target. Schizophr Res. 2017;187:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Millan MJ, Andrieux A, Bartzokis G, et al. Altering the course of schizophrenia: progress and perspectives. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(7):485–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Ogawa F, Malavasi E, Crummie DK, et al. DISC1 complexes with TRAK1 and Miro1 to modulate anterograde axonal mitochondrial trafficking. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(4):906–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Ogawa F, Murphy LC, Malavasi EL, et al. NDE1 and GSK3beta associate with TRAK1 and regulate axonal mitochondrial motility: identification of cyclic AMP as a novel modulator of axonal mitochondrial trafficking. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2016;7(5):553–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Park C, Lee S‐A, Hong J‐H, et al. Disrupted‐in‐schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) and Syntaphilin collaborate to modulate axonal mitochondrial anchoring. Mol Brain. 2016;9(1):69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Park SJ, Lee SB, Suh Y, et al. DISC1 modulates neuronal stress responses by gate‐keeping ER‐mitochondria Ca(2+) transfer through the MAM. Cell Rep. 2017;21(10):2748–2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Vinod KY, Hungund BL. Cannabinoid‐1 receptor: a novel target for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. Expert Opin Ther Tar. 2006;10(2):203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Marsicano G. A cannabinoid link between mitochondria and memory. Nature. 2016;71:75–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Klinedinst NJ, Regenold WT. A mitochondrial bioenergetic basis of depression. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2015;47(1–2):155–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Chen S, Owens GC, Crossin KL, Edelman DB. Serotonin stimulates mitochondrial transport in hippocampal neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;36(4):472–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Chen S, Owens GC, Edelman DB. Dopamine inhibits mitochondrial motility in hippocampal neurons. PLoS One. 2008;3(7):e2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Yan H, Zhang X, Hu W, et al. Histamine H3 receptors aggravate cerebral ischaemic injury by histamine‐independent mechanisms. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Dalmau J, Geis C, Graus F. Autoantibodies to synaptic receptors and neuronal cell surface proteins in autoimmune diseases of the central nervous system. Physiol Rev. 2017;97(2):839–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Zeiler FA, Thelin EP, Donnelly J, et al. Genetic drivers of cerebral blood flow dysfunction in TBI: a speculative synthesis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(1):25–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Hill CS, Coleman MP, Menon DK. Traumatic axonal injury: mechanisms and translational opportunities. Trends Neurosci. 2016;39(5):311–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Han SM, Baig HS, Hammarlund M. Mitochondria localize to injured axons to support regeneration. Neuron. 2016;92(6):1308–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Tkatch T, Greotti E, Baranauskas G, et al. Optogenetic control of mitochondrial metabolism and Ca2+ signaling by mitochondria‐targeted opsins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(26):E5167–E5176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Randall TS, Yip YY, Wallock‐Richards DJ, et al. A small‐molecule activator of kinesin‐1 drives remodeling of the microtubule network. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(52):13738–13743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]