Abstract

Objectives

To compare ultrasonography and abdominal radiography with intravenous urography in the investigation of urinary tract infection in men.

Design

Prospective study in two hospital departments. Radiological procedures and urological assessments performed on different days by different clinicians

Setting

District general hospital.

Participants

Consecutive series of men (n=114) referred to the department of urology for investigation of proved urinary tract infection.

Interventions

Ultrasonography and intravenous urography of renal tract and assessment of urinary flow rate. Clinical assessment, cystoscopy, urodynamic studies, and transrectal ultrasonography with biopsy.

Main outcome measures

Sensitivity and specificity of ultrasonography and abdominal radiography compared with intravenous urography.

Results

Important abnormalities were seen in 53 of 100 fully evaluated patients, the most common being a poorly emptying bladder (34). The combination of plain radiographs of kidneys, ureter, and bladder and ultrasonography detected more abnormalities than intravenous urography alone. No important abnormality was missed by this combination (sensitivity 100% and specificity 93%).

Conclusions

Ultrasonography with abdominal radiography is as accurate as intravenous urography in detecting important urological abnormalities in men presenting with urinary tract infection. This combination is safer than intravenous urography and should be the initial investigation for such patients. Additional determination of urinary flow rate is useful for the assessment of an incompletely emptying bladder.

What is already known on this topic

Ultrasonography alone is the primary investigation of choice for urinary tract infection in children and women

Ultrasonography has limited sensitivity for renal stones and poor sensitivity for ureteric stones

Urinary infection is less common in men than women and the risk factors are different

What this study adds

Ultrasonography is as effective as intravenous urography in men with urinary tract infection only when it is combined with plain radiography

In men aged over 50 an incompletely emptying bladder is the most common abnormality

In such patients determination of urinary flow rate is particularly helpful

Introduction

Ultrasonography with abdominal radiography has now replaced intravenous urography for the investigation of urinary tract infection in children, though minor degrees of renal scarring and reflux may be missed.1–6 Ultrasonography alone is almost as good as intravenous urography for the routine evaluation of women with urinary tract infection,7–11 and plain radiography is not usually performed. Because men have a much lower incidence of urinary tract infection and a higher incidence of stone disease, intravenous urography remains the conventional investigation because underlying anatomical abnormalities may be detected.12,13 Intravenous urography involves the use of ionising radiation and contrast media, the health risks of which are well documented with quantifiable morbidity and mortality.14,15 Ultrasonography is cheaper and quicker than intravenous urography but depends more on the skill of the operator.5

We carried out a prospective study to establish whether abdominal radiography with ultrasonography can detect as many important abnormalities as intravenous urography in men presenting with proved urinary tract infection.

Methods

From January 1995 to December 1996, we investigated 114 men who presented consecutively to the departments of urology and nephrology with proved urinary tract infection. Complete data were obtained on 100 patients. Fourteen men were not included in the analysis (one attended for only one investigation, four did not attend the outpatient appointment, one declined investigation, eight had incomplete data). Ultrasonography and intravenous urography were performed on separate days and by different radiologists. At the time of the study the standard investigation in adult men with a proved urinary tract infection was intravenous urography. As ultrasonography does not have any biophysical ill effects we did not obtain formal consent from the patients for this additional investigation. The local ethics committee subsequently approved the study.

The results of the first investigation, usually intravenous urography, were not known at the time of the second investigation. All ultrasound examinations were performed with a 3.5 MHz probe on various ultrasound scanners. Each kidney was assessed in the longitudinal and transverse planes and renal length was recorded. The bladder was assessed with the bladder full and after micturition. The volume after micturition was considered relevant if it was greater than 100 ml. Urinary flow rates were assessed in the department of radiology with a Dantec Urodyn 1000. Determination of flow rates was judged acceptable if >150 ml urine was voided.

Intravenous urography comprised a full length plain film, an immediate cross kidney film after injection of contrast media, a seven minute cross kidney film, a 15 minute full length film, and a bladder film after micturition. Tomography was used at the discretion of the supervising radiologist.

Findings of all three investigations were recorded separately. For each patient we compared the results of ultrasonography alone, ultrasonography with plain radiography, and intravenous urography. We divided the urinary tract into the upper tract (defined as the kidneys and ureters) and the lower tract (bladder, prostate, and urethra). We also recorded incidental findings in other systems. Statistical analysis was performed with the χ2 test.

After the radiological assessments we saw and examined patients in the department of urology. We recorded fever, flank pain, frequency, burning, and frank haematuria and noted the presence of diabetes and whether or not infections were recurrent. Subsequent investigations included additional measurements of flow rates, cystoscopy, urodynamic assessment, and transrectal ultrasonography, when appropriate. Clinical diagnosis was on the basis of history, examination, and these investigations.

Results

The mean (range) age of participants was 54 (18-88) years. Fifty three had had only one single infection, and 47 had more than one documented episode. We assessed 62 men with cystoscopy and four with full urodynamic investigation. We assessed flow rates in 90. Nine patients underwent transrectal ultrasonography. Of these, three underwent biopsy, and two were found to have prostate cancer. Table 1 summarises the results and compares the two radiological techniques. Fifty three patients had a detectable abnormality considered to be clinically significant. All important abnormalities detected by intravenous urography were also detected by ultrasonography or abdominal radiography. Table 2 shows incidental abnormalities.

Table 1.

Findings in 100 adult men with proved urinary tract infection, according to method of investigation

| Ultrasonography and x ray | Intravenous urography | |

|---|---|---|

| Upper tract: | ||

| Hydronephrosis | 8 | 7 |

| Kidney stone | 3 | 3 |

| Ureteric stone | 2 | 2 |

| Small/scarred kidney | 4 | 3 |

| Pelvic kidney | 1 | 1 |

| Ureteric dilatation | 0 | 3 |

| Lower tract: | ||

| Residual urine | 34 | 26 |

| Diverticulum | 6 | 7 |

| Bladder stone | 1 | 1 |

Table 2.

Incidental findings in 100 men with proved urinary tract infection, according to method of investigation

| Ultrasonography and x ray | Intravenous urography | |

|---|---|---|

| Renal cysts | 9 | 4 |

| Duplex without dilatation | 3 | 6 |

| Gall stones | 3 | 0 |

| Minor spinal abnormalities | 2 | 0 |

| Fetal lobulation of kidney | 1 | 1 |

Ultrasonography detected hydronephrosis in eight patients. In one case intravenous urography showed that the collecting system was within normal limits. Ultrasonography alone missed five out of six cases of urinary tract stones, but all were detected with the addition of plain radiography. In two cases ultrasonography misdiagnosed stones that were not detected by plain radiography or intravenous urography. In one case plain radiography misdiagnosed a stone not seen on intravenous urography. Although ultrasonography missed a bladder stone, this patient had been catheterised and the bladder was therefore empty. Three small, scarred kidneys were found by both methods. In one man ultrasonography misdiagnosed one kidney as small and scarred that was subsequently shown to be normal on intravenous urography.

Both methods identified a pelvic kidney. Ultrasonography failed to detect three cases of ureteric dilatation. Two of these, however, had dilatation secondary to ureteric stones that were seen on the plain radiograph, the other had associated hydronephrosis secondary to chronic retention that was seen on ultrasonography. Intravenous urography identified two patients with non-functioning kidneys. Ultrasonography showed that these kidneys were small and scarred.

Ultrasonography detected a poorly emptying bladder in 34 patients compared with 26 detected with intravenous urography. Ultrasonography alone missed one bladder diverticulum. Table 3 shows the final clinical diagnosis in 100 men. Table 4 shows the ability of abdominal radiography and ultrasonography to detect abnormalities seen on intravenous urography.

Table 3.

Clinical diagnosis in 100 adult men with proved urinary tract infection

| No of men* | |

|---|---|

| Bladder outflow obstruction | 36 |

| Underactive detrusor | 7 |

| Bladder diverticulum | 7 |

| Chronic retention | 4 |

| Urethral stricture | 3 |

| Renal stone | 3 |

| Ureteric stone | 2 |

| Prostatitis | 3 |

| Prostate cancer | 2 |

| Pelviureteric obstruction | 2 |

| Bladder stone | 1 |

| Pelvic kidney | 1 |

| Phimosis | 1 |

Several men had more than one diagnosis.

Table 4.

Ability of ultrasonography and abdominal radiography (x ray) to detect abnormalities seen on intravenous urography (sensitivity 100%, specificity 93%, positive predictive value 0.95, negative predictive value 1.0, accuracy 97%)

| Ultrasonography with radiography |

Intravenous urography

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |

| Positive | 56 | 3 |

| Negative | 0 | 41 |

Discussion

We have shown in this series that plain radiography with ultrasonography of the renal tract will detect most clinically important abnormalities that would normally be shown on intravenous urography. Patients with urinary tract infection are investigated to discover any underlying disease process which, if treated, will prevent or reduce further infections. In our study over half of the men with proved urinary tract infection had some abnormality.

The incompletely emptying bladder

The most common abnormality was an incompletely emptying bladder, either because of obstructed outflow, an underactive detrusor, or urethral stricture. Four out of seven patients with an underactive detrusor were diagnosed with formal urodynamic assessment. Patients with obstructed outflow were diagnosed either with urodynamics or clinically in the presence of a low urinary flow together with an incompletely emptying bladder in accordance with standard urological practice. The proportion of patients with obstruction was significantly higher in men aged over 50 years, which is predictable in view of the high prevalence of benign prostatic hypertrophy.16

The high proportion of patients who produced satisfactory measurements of flow rate was mainly due to the presence of a flow rate machine in the radiology department so that patients were confirmed to have a full bladder before micturition. The usefulness of such measurements in this group of patients has previously been emphasised by other authors,13,17 but this has not been widely adopted. Our series indicates that for patients with a poorly emptying bladder a clinical diagnosis can usually be made with ultrasonography and flow rate; formal urodynamic studies are necessary in only a minority. Flow rate measurements are also helpful in the diagnosis and management of prostatitis.18

Stones

Ultrasonography alone is not as effective as intravenous urography in the diagnosis of urinary tract stone disease, and indeed in our series five of the six cases of urinary tract stones were missed on ultrasonography alone. With the addition of plain radiography all the urinary tract stones were diagnosed, although without the additional information of precise site and degree of obstruction that intravenous urography would have shown.

If a proteus or another organism that can split urea is isolated from the urine the chance of underlying stone disease is considerably higher.19 The high overall rate of abnormality in our series is similar to that reported by Maskell in 1989, even though we used less rigorous microbiological criteria to select patients for further investigation.20

Upper tract dilatation and scarring

Ultrasonography misdiagnosed hydronephrosis in one patient. Dilatation, however, does not equate with obstruction, and it was only with the additional anatomical and functional information from intravenous urography that we could say that this patient's collecting system was normal. Ultrasonography wrongly diagnosed a small kidney that was subsequently shown to be normal on intravenous urography. In the two patients in whom a unilateral non-functioning kidney was seen on intravenous urography, ultrasonography also showed the kidneys to be small and scarred.

In 1990 Spencer et al compared use of ultrasonography with intravenous urography in men and women.21 They showed the usefulness of ultrasonography and said that without the additional use of plain radiography a considerable number of abnormalities would be missed. They also found a high proportion of patients with incompletely emptying bladders, but the causes were not clear. This observation and our data should encourage the use of flow rate machines for patients presenting with urinary tract infection.

Safety

Previous authors have highlighted the added safety of ultrasonography compared with intravenous urography,5,21 and certainly there is a saving in cost and time. Figures from the National Radiation Protection Board show that the radiation dose of an intravenous urographic examination is 2.5 mSv. This is equivalent to 14 months' background radiation and comes at a risk of induction of fatal cancer (in patients aged 16-69 with an average life expectancy) of 1:8000. The radiation dose of a normal plain radiograph is 0.7 mSv, which is equivalent to four months' background radiation and a risk of cancer of 1:30 000. The latest ionising radiation (medical exposure) regulations underline the importance of justifying all medical exposure to x rays and encourage appropriate use of alternatives.15

Ultrasonography has specific advantages over intravenous urography in the assessment of the lower urinary tract, including a measure of volume after micturition and size and projection of the prostate. Urologists use these features in recommending different treatments for obstruction of bladder outflow.

Incidental findings and symptoms

The importance and usefulness of incidental findings varies according to clinical presentation. In patients with right flank pain an ultrasound examination that shows gallstones may be helpful. Uncomplicated duplex collecting systems without dilatation were judged to be unimportant; if obstruction is present ultrasonography usually shows dilatation. Spinal abnormalities such as sacral agenesis may be important in younger patients with a suspected neuropathic bladder.

The subgroup analysis that correlated symptoms with clinical diagnosis showed an increased incidence of lower tract abnormalities in patients aged over 50 years. This might be expected in view of the age related causes of obstruction of outflow, including benign prostatic hyperplasia and carcinoma of the prostate. Fever and flank pain may indicate pyelonephritis, but studies have shown a high incidence of these symptoms in patients in whom infection was localised to the bladder.22,23 In our study neither flank pain nor fever correlated with an upper tract abnormality, and over half such patients had no abnormality at all. Fever and flank pain are not indications for intravenous urography. We found these symptoms unhelpful in predicting whether an upper or lower tract abnormality was present, and there was no added relevance if a patient had recurrent urinary tract infection or diabetes.

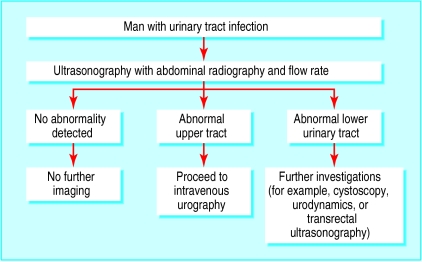

Ultrasonography can detect stones at the vesicoureteric junction but cannot easily show the normal ureter or ureteric calculi in other positions; it can, however, show any secondary dilatation of the pelvicaliceal system. An intravenous urogram is superior in these circumstances and would therefore be the next investigation. We propose the algorithm outlined in the figure for men with a proved urinary tract infection and agree that the high proportion of underlying abnormalities justifies active investigation in these patients.20,24,25 Specialist referral is not indicated in younger men with normal results on ultrasonography and plain radiography who recover from the infection and regain normal flow.

Conclusions

Intravenous urography remains an important investigation, particularly in the assessment of stone disease, upper tract obstruction, and any abnormalities seen on plain film and ultrasonography. In view of the hazards of ionising radiation and contrast media, however, ultrasonography, radiography, and determination of flow rate should be the initial investigations of choice in men presenting with a symptomatic and proved urinary tract infection.

Figure.

Proposed algorithm for investigations of men with urinary tract infection

Acknowledgments

Ann Frost and Jayne Clarke typed the manuscript, and the audit department of the Lister Hospital retrieved the case records.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Alon U, Pery M, Davidai G, Berant M. Ultrasonography in the radiologic evaluation of children with urinary tract infection. Pediatrics. 1986;78:58–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindsell D, Moncrieff M. Comparison of ultrasound examination and intravenous urography after a urinary tract infection. Arch Dis Child. 1986;61:81–82. doi: 10.1136/adc.61.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kenda R, Kenig T, Silc M, Zupancic Z. Renal ultrasound and excretory urography in infants and young children with urinary tract infection. Pediatr Radiol. 1989;19:299–301. doi: 10.1007/BF02467297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kangarloo H, Gold RH, Fine RN, Diament MJ, Boechat MI. Urinary tract infection in infants and children evaluated by ultrasound. Radiology. 1985;154:367–373. doi: 10.1148/radiology.154.2.3880909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewis-Jones HG, Lamb GHR, Hughes PL. Can ultrasound replace the intravenous urogram in preliminary investigation of renal tract disease? A prospective study. Br J Radiol. 1989;62:977–980. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-62-743-977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sherwood T, Whitaker RH. Initial screening of children with urinary tract infections: is plain film radiography and ultrasonography enough? BMJ. 1984;288:827. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6420.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fair WR, McClennan BL, Jost RG. Are excretory urograms necessary in evaluating women with urinary tract infection? J Urol. 1979;121:313–315. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)56766-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engel G, Schaeffer AJ, Grayhack JT, Wendel EF. The role of excretory urography and cystoscopy in the evaluation and management of women with recurrent urinary tract infection. J Urol. 1980;123:190–191. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)55849-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fowler JE, Jr, Pulaski ET. Excretory urography, cystography, and cystoscopy in the evaluation of women with urinary-tract infection: a prospective study. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:462–465. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198102193040805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fairchild TN, Shuman W, Berger RE. Radiographic studies for women with recurrent urinary tract infections. J Urol. 1982;128:344–345. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)52918-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNicholas MM, Griffin JF, Cantwell DF. Ultrasound of the pelvis and renal tract combined with a plain film of abdomen in young women with urinary tract infection: can it replace intravenous urography? A prospective study. Br J Radiol. 1991;64:221–224. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-64-759-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipsky BA. Urinary tract infections in men. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:138–150. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-2-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Booth CM, Whiteside CG, Milroy EJ, Turner-Warwick RT. Unheralded urinary tract infection in the male. A clinical and urodynamic assessment. Br J Urol. 1981;53:270–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1981.tb06104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ansell G, Bettmann MA, Kaufman JA, Wilkins RA, editors. Complications in diagnostic imaging and interventional radiology. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwall Science; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposures) Regulations 2000, National Radiation Protection Board 2000. www.nrpb.org.uk (accessed Oct 2001).

- 16.Garraway WM, Collins GM, Lee RJ. High prevalence of benign prostatic hypertrophy in the community. Lancet. 1991;338:469–471. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90543-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lepor H. Benign prostatic hyperplasia. In: Walsh PC, Retik AB, Vaughan ED, Wein AJ, editors. Campbell's urology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1998. pp. 1453–1477. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nickel JC. Prostatitis: evolving management strategies. Urol Clin North Am. 1999;26:737–751. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pead L, Maskell R. Urinary tract infection in adult men. J Infect. 1981;3:71–78. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(81)92386-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maskell R. Urine microscopy and culture in the selection of patients for urinary tract investigation. Br J Urol. 1989;63:7–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1989.tb05113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spencer J, Lindsell D, Mastorakou I. Ultrasonography compared with intravenous urography in investigation of urinary tract infection in adults. BMJ. 1990;301:221–224. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6745.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huland H, Busch R, Riebel T. Renal scarring after symptomatic and asymptomatic upper urinary tract infection: a prospective study. J Urol. 1982;128:682–685. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)53133-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Busch R, Huland H. Correlation of symptoms and results of direct bacterial localisation in patients with urinary tract infections. J Urol. 1984;132:282–285. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gower PE. Urinary tract infections in men. Investigate at all ages. BMJ. 1989;298:1595–1596. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6688.1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaeffer AJ. Infections of the urinary tract. In: Walsh PC, Retik AB, Vaughan ED, Wein AJ, editors. Campbell's urology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1998. pp. 533–614. [Google Scholar]