Abstract

Chemotherapy is now in common use for the treatment of tumors; however, with tumor growth retardation comes the severe side effects that occur after a chemotherapy cycle. Eicosapentaenoic acids (EPA) used in combination with chemotherapy has an additive effects and provides a rationale for using EPA in tandem with chemotherapy. To improve the efficacy and safety of this combination therapy, a further understanding that EPA modulates with the tumor microenvironment is necessary. Connexin 43 (Cx43) is involved in enhancing chemosensitivity that was suppressed in a tumor microenvironment. We aim to investigate the role of EPA in chemosensitivity in murine melanoma by inducing Cx43 expression. The dose-dependent upregulation of Cx43 expression and gap junction intercellular communication were observed in B16F10 cells after EPA treatment. Furthermore, EPA significantly increased the expression levels of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) signaling pathways. The EPA-induced Cx43 expression was reduced after MAPK inhibitors. Knockdown Cx43 in B16F10 cells reduced the therapeutic effects of combination therapy (EPA plus 5-Fluorouracil). Our results demonstrate that the treatment of EPA is a tumor induced Cx43 gap junction communication and enhances the combination of EPA and chemotherapeutic effects.

Keywords: Eicosapentaenoic acids, Connexin 43, 5-Fluorouracil, combination therapy

Introduction

Gap junctions are involved in cellular electrical and metabolic activities. A connexon is made up of six connexins. Connexins are the predominant gap junction protein in vertebrates. Connexin 43 (Cx 43) bridges channels between adjacent cells and allows the exchange of small molecules. Cx43 can facilitate the passage of chemotherapy drugs or death signals between neighboring tumor cells 1. Many tumor cells are characterized by dysfunction or reducing expression of Cx43 2. Cx43 has the correct effect on chemotherapy 1, 3, 4. The amino acid peptide drug (αCT-1) that mimics a cytoplasmic region of Cx43 and had the ability of Cx43-mediated gap junctional intercellular communication, leading to the improved efficacy of chemotherapy 5. The ability of retinoic acid reversed tumor metastasis in chemoresistant cells through the upregulation of Cx43 6.

Omega-3 fatty acids, including eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), are derived from marine plants and animals. Humans obtain these from dietary sources, because humans are not able to synthesize EPA 7. EPA has anti-inflammatory and antitumor abilities that work by regulating cellular signal pathways 8. EPA modulated in immunity and inhibits the expression of intracellular interleukin-2, tumor necrosis factor -α, and interleukin-4 in T cells 9. Previously, we found that EPA did not influence the proliferation of T cells 8. Meanwhile, EPA reduced the function of antigen-presenting cells 10, 11. Recently, we demonstrated that EPA induced host antitumor immunity by inhibiting tumor indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO) expression. EPA has potential as a cancer therapy 8. The combination of EPA and chemotherapy had delayed tumor growth 12. Recently, the relationship between EPA and Cx43 expression in cardiomyocytes has been demonstrated 13 but the role of EPA in the expression of cx43 in tumor cells remains unknown. In this study, we elucidate whether EPA can enhance the responses to chemotherapy by upregulating Cx43.

Material and Methods

Cell lines, reagents and mice

B16F10 murine melanoma cells were routinely maintained in Dulbecco's.

Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 25 mM glucose, and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), as previously described 14. EPA, SB203580, SP600125, 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU), and Lucifer yellow were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The working concentrations of the inhibitors were as follows: 25 μM SB203580 (Sigma-Aldrich), or 10 μM SP600125 (Sigma-Aldrich) 3. Cells were pretreated with various inhibitors for 1 h, then EPA (100 μM) was added to cells for 24 h. Male C57BL/6 mice aged 6-8 weeks were purchased from the National Laboratory Animal Center of Taiwan. Adulthood is biologically defined as the age at which human or other organisms reach sexual maturity. Mice come of mating age sometime between 6-8 weeks of age. Adult mice 6-20 weeks old are the best to carryout studies 15, 16. The animals were maintained in specific pathogen-free animal care facility under isothermal conditions with regular photoperiods. The experimental protocol adhered to the rules of the Animal Protection Act of Taiwan and was approved by the Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Sun Yat-sen University (the permit number: 10714).

Western blotting

Cells with various treatments were collected and lysed in lysed buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40), 50 mM Tris-Cl). The bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA) was used to test protein content. Proteins were fractionated on SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with antibodies against Cx43 (synthetic peptide corresponding to the C-terminal segment of the cytoplasmic domain of human/rat Cx43, C6219, Sigma-Aldrich), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Santa Cruz, CA, USA), phosphor-ERK (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), p38 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), phosphor-p38 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), c-jun N terminal kinase (JNK) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), phosphor-JNK (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) or monoclonal antibodies against β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG were used as the secondary antibody and protein-antibody complexes were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence system 17.

Analysis of Cx43 transcriptional activity

Cells were used lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to cotransfected with luciferase reporter plasmids driven by Cx43 promoters (0.66 μg) 1 and pTCYLacZ (0.34 μg), which is a β-galactosidase (β-gal) expression plasmid driven by the β-actin promoter. Then, cells were treated with EPA (0-100 μM) and cell lysates were harvested at different concentrations after 6 h transfection. The cell lysates were assessed for their luciferase activities as determined by a dual-light luciferase and β-gal reporter gene assay system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) using a luminometer (Minilumate LB9506, Bad Wildbad) 3. Relative luciferase activity was measured as luciferase activity divided by β-gal activity to normalize transfection efficiency per microgram protein. Meanwhile, the BCA protein assay (Pierce) was used to determine protein content in each sample.

Cell viability assay

EPA-treated, non-treated, or transfected cells were exposed to 0-40 μM of 5-FU under for 48 h. Cell viability was determined with a colorimetric WST-8 (Dojindo Labs, Tokyo, Japan) assay and expressed as the mean of the percentage of surviving cells relative to that of the cells in the absence of 5-FU 17.

Knockdown of Cx43

The specific shRNA of Cx43 plasmids (sc-35091-SH, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. B16F10 cells were used lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogene) to transfected with Cx43 shRNA or control shRNA plasmids 1.

Cx43 functional assay

By using fluorescent dye, lucifer yellow (Sigma-Aldrich), levels of gap junctional intercellular communication in non-treated and EPA-treated cell in culture were determined scrape loading and dye transfer technique. Scrape loading was performed applying cuts on cell monolayer with a razor blade, and then 0.5% lucifer yellow was added to the cells. The dye was rinsed away after 5 min. Cells were washed PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and cells stained with lucifer yellow were detected by fluorescence microscope at magnification of ×200 1, 3. The dye-spreading area was quantified by measuring the fluorescent area in three flied at the center of the scrape line using QCapture Pro 6.0 (QImaging, Surrey, BC, Canada).

Animal study

A group of 8 mice were inoculated subcutaneously with 106 B16F10 cells at day 0, and at day 7 nodules developed at all injection sites with an approximate tumor volume of 80 mm3. Groups of tumor-bearing mice were orally administrated with EPA (25 mg/kg) at day 7 followed by 5-FU (40 mg/kg) treatment on days 9, 11, and 13, or with either treatment alone. All mice were monitored for tumor growth and survival as previously described 3. A tumor burden greater than 10% body weight or tumor diameter exceeding 20 mm in an adult mouse was performed euthanasia.

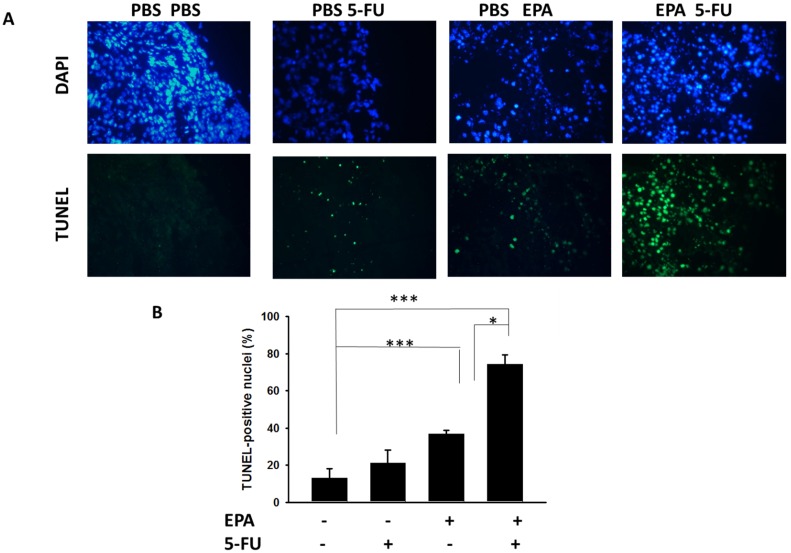

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end-labeling (TUNEL) assay

Mice were inoculated with 106 B16F10 cells at day 0. Groups of 6 tumor-bearing mice were orally administrated with EPA (25 mg/kg) at day 7 for a week followed by 5-FU (40 mg/kg) treatment at days 9, 11, and 13, or with either treatment alone. Then, tumors were excised and snap frozen at day 15. TUNEL assay was used to detect cell apoptosis within tumors and was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). Nuclei were stained with 50 μg/ml of DAPI. TUNEL-positive cells were counted under the microscope. We counted three high-power (× 200) fields that showed highest density of positive-stained cells per field to determine the average percentage of apoptotic (TUNEL positive) cells in each section 1.

Statistical analysis

The ANOVA was used to determine differences between groups. The survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier survival curve and log-rank test. Any P value less than 0.05 is regarded as statistically significant.

Results

EPA-induced Cx43 expression and gap junction intercellular communication in B16F10 cells

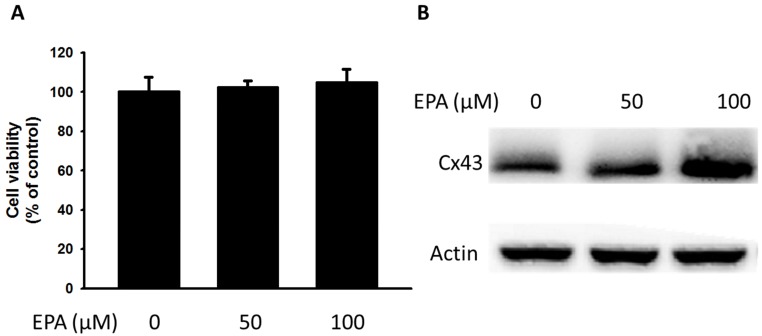

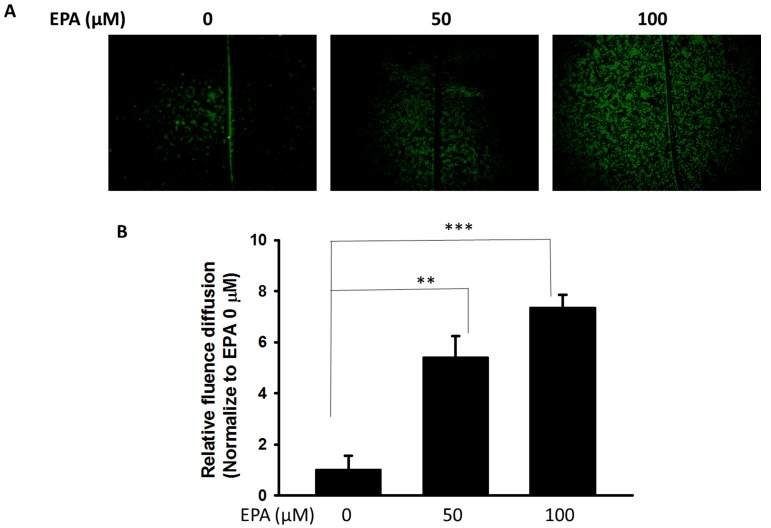

The potential cytotoxic effects of EPA (0~100 μM) were measured by using WST-8 assay. At concentration up to 100 μM EPA, no cytotoxic effects were observed on B16F10 cells treated for 24 h (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, to examine the effect of EPA on Cx43 levels in murine melanoma cells (B16F10), B16F10 cells were incubated with different concentrations of EPA, and then measured by Western blotting. Treatment of B16F10 cells with 0, 50, 100 μM of EPA induced a dose-dependent increase in Cx43 levels compared to controls (Fig. 1B). To examine the extent to which Cx43 expression was related to gap junction intercellular communication in B16F10 cells, the gap junction permeable fluorescent dye lucifer yellow was used to perform the scrape loading/dye transfer assay. The gap junction function showed an increased level of dye transport in B16F10 cells (Fig. 2A). The results were consistent with the presence of Cx43 in cells treated with EPA. The dye transfer in B16F10 cells was higher after 100 μM EPA treatment than that in control treatment (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, our results show that degrees of gap junction intercellular communication were correlated with the expression of Cx43 induced by EPA in melanoma cells (Fig. 2B). These results suggested that EPA might induce Cx43 expression and increase the function of Cx43 in gap junction intercellular communication.

Figure 1.

Effects of EPA on the expression of Cx43 in tumor cells. (A) B16F10 cells were treated with EPA (0-100 μM) for 24 h. The number of cell was measured by the WST-8 assay. (B) The B16F10 cells were treated with of EPA for 24 h. The B16F10 cells were collected and measured for Cx43 by Western blotting. The Immunoblotting assay was repeated three times with similar results.

Figure 2.

EPA induced gap junction intercellular communication in B16F10 cells. (A) The B16F10 cells treated for 24 h with different concentrations of EPA were determined by scrape loading and dye transfer analysis. (B) The gap junction intercellular communication was expressed as fold of the control. (n = 6, data are mean± SD. ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001).

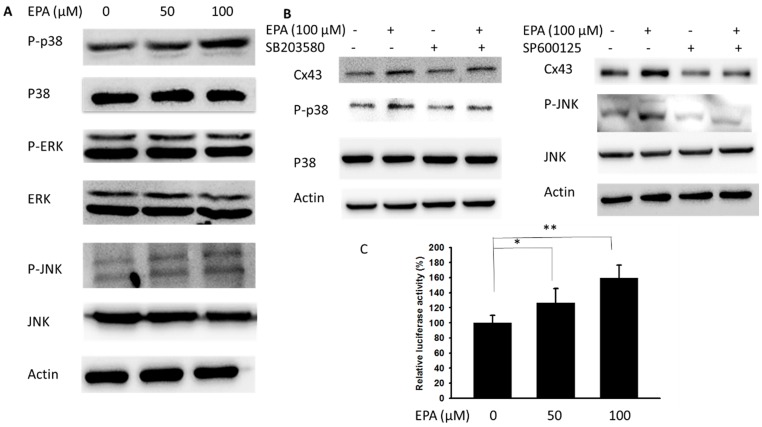

EPA enhanced Cx43 expression through the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) signaling pathways

Further, the potential molecular mechanisms in EPA-induced Cx43 expression were determined in B16F10 cells. Recently, a different MAPK kinase expression might involve the particles-induced regulation of Cx43 expression 18. In this study, the phosphorylation of JNK and p38 were increased after EPA treatment, but the phosphorylation of ERK was not observed (Fig. 3A). There were no significant effects on the phosphorylation of ERK expression after EPA treatment in B16F10 cells. Meanwhile, EPA-induced Cx43 protein expression was blocked by inhibitor of p38 (SB203580) and JNK (SP600125) in B16F10 cells (Fig. 3B). By using the inhibitor of p38 and JNK, EPA-induced Cx43 expression was reduced in B16F10 cells (Fig. 3B). An important function of MAPKs signaling pathway is to activate transcription factors that can regulate gene expression. By using promoter reporter assay, the effect of EPA on the Cx43 promoter activity was examined. The ratio of luciferase activity in B16F10 cells was higher in 100 μM EPA treatment than that in control treatment (Fig. 3C). The p38 and JNK play impartment roles in EPA-induced Cx43 expression in B16F10 cells.

Figure 3.

MAPK inhibitors reduced EPA-induced Cx43 expression. (A) The B16F10 cells were treated with EPA (0-100 μM) for 24h. The cells were lysed and protein expression of ERK, P38, JNK, P-ERK, P-P38, and P-JNK was examined. (B) After treatment of cells with inhibitor for p38 (SB203580) and JNK (SP600125) for 1h, The B16F10 cells were treated with EPA (100 μM) for 24h. The cells were lysed and protein expression of Cx43, P-P38, P-P38, JNK and p-JNK was examined. (C) EPA induced Cx43 transcriptional activity in B16F10 cells. The B16F10 cells transfected with luciferase gene under the control of Cx43 promoter were treated with EPA (0-100 μM) for 24 h. The transcriptional activity of Cx43 was determined by the luciferase reporter assay and is expressed as the fold of the relative luciferase activity relative to that in the control tumor cells. (n = 4, data are mean± SD. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01).

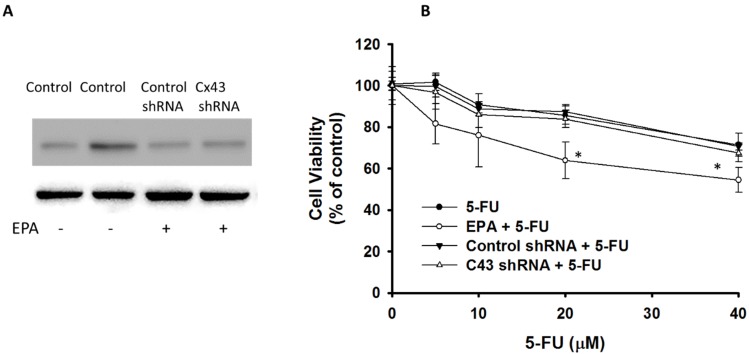

EPA increased the susceptibility of B16F10 cells to 5-FU

To further examine the relationship between Cx43 expression and chemotherapy-induced cytotoxicity, the cell viability of B16F10 cell was measured after 5-FU, EPA or EPA combined with 5-FU treatment. Under 5-FU treatment, the cell viability in EPA-treated cells was significantly reduced as compared to untreated cells (Fig. 4). The role of Cx43 in EPA-induced additive cytotoxic effect was further studied by using knockdown Cx43 in B16F10 cells (Fig. 4A). When the expression of Cx43 was downregulated, the combo therapy induced additive cytotoxic activity was not observed (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that Cx43 plays an important role in the susceptibility of B16F10 cells to 5-FU.

Figure 4.

EPA-induced Cx43 expression in combination with 5-FU exerted cytotoxic effects on B16F10 cells. (A) EPA-treated or control cells were transfected with Cx43 shRNA or control plasmids. The expression of Cx43 was determined by Western blotting in B16F10 cells. (B) Down-regulation-Cx43 expression eliminated the cytotoxic effect of 5-FU. EPA-treated or control cells were transfected with Cx43 shRNA or control plasmids. The cells were exposed to 5-FU (0-40 μM) for 24 h followed by determination of their viability by the WST-8 assay. (n = 6, data are mean± SD. * P < 0.05).

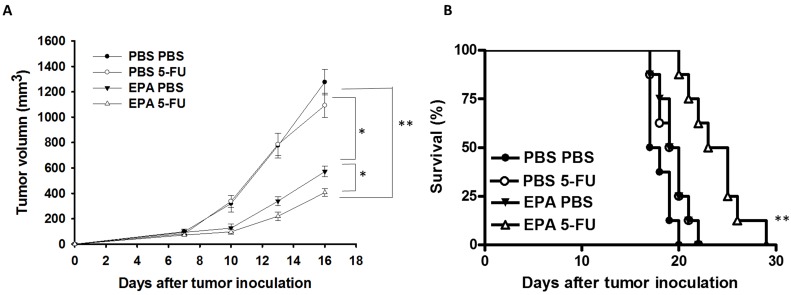

EPA in combination with 5-FU enhanced the antitumor activity

The B16F10-bearing mice were evaluated the antitumor effects of EPA in combination with 5-FU. Fig. 5A shows that EPA slightly inhibited tumor growth in comparison with these in PBS-treated control mice. The combination therapy of EPA and 5-FU significantly inhibited the tumor growth. The low-dose 5-FU group did not show any antitumor activity. The tumor volume of mice treated with the combo therapy was reduced 53.26% when compared with those in the PBS-treated group. The tumor volume of EPA-treated group inhibited 31.18% compared with those in the PBS-treated group. The mice treated with EPA plus 5-FU enhanced the survival of tumor-bearing mice compared with the mice treated with PBS, but the survival of the mice treated with EPA was not observed with similar results (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, the tumor sections from B16F10-bearing mice treated with PBS, EPA or 5-FU alone, or in combination were analyzed by a TUNEL assay. The TUNEL assay showed an increase in the number of cells undergoing apoptosis in the EPA-treated tumors compared with the PBS-treated tumors (Fig. 6A and B). Few signals were observed in the low-dose 5-FU group. There was a 5.73-fold increase in the number of apoptotic cells induced by EPA plus 5-FU compared with these in the control group (Fig. 6B). Taken together, EPA could reduce tumor growth in the murine tumor model and EPA combined with 5-FU shows signs of additive antitumor effects.

Figure 5.

Additive antitumor effects of combo therapy. Groups of 8 mice that had been inoculated subcutaneously with B16F10 cells (106) at day 0. Groups of B16F10 tumor-bearing mice were orally administrated with EPA (25 mg/kg) at day 7 followed by 5-FU (40 mg/kg) treatment on days 9, 11, and 13, or with either treatment alone. (A) The tumor volume was measured. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the mice bearing B16F10 tumors. (* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01).

Figure 6.

The combo therapy increased tumor cells undergoing apoptosis. Groups of 6 mice that had been inoculated subcutaneously with B16F10 cells (106) at day 0. Groups of B16F10 tumor-bearing mice were orally administrated with EPA (25 mg/kg) at day 7 followed by 5-FU (40 mg/kg) treatment on days 9, 11, and 13, or with either treatment alone. (A) Tumors were excised at day 15, and TUNEL assay was used to detect apoptotic cells (× 400). (B) TUNEL-positive cells were counted from three fields of highest density of positive-stained cells in each section to determine the percentage of apoptotic cells. (n=4, data are mean± SD. * P < 0.05; *** P < 0.001).

Discussion

Intercellular communication was reduced during tumor formation. The antitumor activity of chemotherapeutic agents was enhanced by increasing gap junction activity in tumor cells 19. Treatment with EPA results in Cx43 up-regulated in tumor cells. When the expression of Cx43 in cells was reduced, cell death was increased after 5-FU treatment. A low dose 5-FU alone did not significantly decrease tumor growth in vivo as this combinational therapy of EPA and 5-FU showed a 68.17% reduction when compared with the control group. An increase in the amount of tumor cells undergoing apoptosis was observed in tumor sections. Our results have demonstrated that an increase in the antitumor activity of 5-FU via enhancement of gap junction expression with EPA.

The tumor volume of B16F10-bearing mice treated with the EPA was reduced 55.19% in comparison with the control groups. Many studies have demonstrated that tumor apoptosis is induced by EPA treatment 12, 20. EPA combined with chemotherapy results in the inhibition of tumor growth 12. EPA can directly induce tumor cell death through a different pathway in other studies. The intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways were triggered after EPA treatment 12. However, EPA also played a role in changing the lipid raft and inhibiting the oncoprotein 20, 21. EPA disrupted the mitochondrial membrane potential and induced oxidative stress in tumor cells 20. Demethylating agents may promote tumor suppressor gene re-expression. Fortunately, it has been demonstrated that EPA induces DNA demethylation in solid tumor cells 22. EPA dose not reduce the growth of breast cancer cells in vitro, but the mechanisms, which may involve microRNA (miRNA), have been demonstrated 23. Meanwhile, EPA directly suppresses T cell proliferation by inhibiting IL-2 expression and IL-2 receptor production 24. Although EPA did not significantly influence the viability of B16F10 cells in vitro (Fig. 1A), EPA inhibited tumor growth in vivo (Fig. 5A and 6). Recently, EPA has antitumor activity and modulates tumor immune tolerance 8. Our recent studies pointed out that EPA decreased tumor IDO expression and increased host T cell viability. The oral administration of EPA in tumor-bearing mice may destroy the immunosuppressive phenotype of tumor microenvironment. EPA is a potent adjuvant that induces antitumor immunity by reducing the expression of IDO in tumor microenvironment. In the present study, the results of the TUNEL assay showed EPA-treated group had the almost 2.83-folds signals compared with that in PBS-treat group. EPA as tumor immune checkpoint inhibitors may result in more apoptosis signals and the delay tumor growth by attracting active host T cells.

Recent studies revealed that natural products or nanoparticles enhanced Cx43 expression by regulating MAPK signaling pathways 3, 18. We studied the effect of EPA on Cx43 expression and function in the present study. EPA increases the activation of p38 and JNK pathway and is thought to involve in the upregulation of Cx43. We suggest that EPA combined with 5-FU holds promise as potential therapies for tumors by taking advantage of the antitumor activity of 5-FU and pleiotropic effects of EPA.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Kaohsiung Municipal Ta-Tung Hospital research project, (kmtth-107-008), China Medical University research project (CMU104-S-03) and NSYSU-KMU JOINT RESEARCH PROJECT (#NSYSUKMU 108-P030).

Author Contributions

C.J.Y.; and C.H.L conceived, designed and revised the experiments; C.T.K, C.J.Y, L.H.W, and M.C.C. performed the experiments; C.R.P, N.P. and C.H.L. analyzed the data; C.J.Y. Y.H.C., W.L. and C.H.L. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; C.J.Y. and C.H.L wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Chang WW, Lai CH, Chen MC, Liu CF, Kuan YD, Lin ST, Lee CH. Salmonella enhance chemosensitivity in tumor through connexin 43 upregulation. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:1926–1935. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saccheri F, Pozzi C, Avogadri F, Barozzi S, Faretta M, Fusi P, Rescigno M. Bacteria-induced gap junctions in tumors favor antigen cross-presentation and antitumor immunity. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:44ra57. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng YJ, Chang MY, Chang WW, Wang WK, Liu CF, Lin ST, Lee CH. Resveratrol enhances chemosensitivity in mouse melanoma model through connexin 43 upregulation. Environ Toxicol. 2015;30:877–886. doi: 10.1002/tox.21952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin HC, Yang CJ, Kuan YD, Wang WK, Chang WW, Lee CH. The inhibition of indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase 1 by connexin 43. Int J Med Sci. 2017;14:1181–1188. doi: 10.7150/ijms.20661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grek CL, Rhett JM, Bruce JS, Abt MA, Ghatnekar GS, Yeh ES. Targeting connexin 43 with α-connexin carboxyl-terminal (ACT1) peptide enhances the activity of the targeted inhibitors, tamoxifen and lapatinib, in breast cancer: clinical implication for ACT1. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:296. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1229-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi G, Zheng X, Wu X, Wang S, Wang Y, Xing F. All-trans retinoic acid reverses epithelial-mesenchymal transition in paclitaxel-resistant cells by inhibiting nuclear factor κ B and upregulating gap junctions. Cancer Sci. 2019;110:379–388. doi: 10.1111/cas.13855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee CH, Lee SD, Ou HC, Lai SC, Cheng YJ. Eicosapentaenoic acid protects against palmitic acid-induced endothelial dysfunction via activation of the AMPK/eNOS pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:10334–10349. doi: 10.3390/ijms150610334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang CC, Yang CJ, Wu LH, Lin HC, Wen ZH, Lee CH. Eicosapentaenoic acid reduces indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 expression in tumor cells. Int J Med Sci. 2018;15:1296–1303. doi: 10.7150/ijms.27326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaudszus A, Gruen M, Watzl B, Ness C, Roth A, Lochner A, Barz D, Gabriel H, Rothe M, Jahreis G. Evaluation of suppressive and pro-resolving effects of EPA and DHA in human primary monocytes and T-helper cells. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:923–935. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P031260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujikawa M, Yamashita N, Yamazaki K, Sugiyama E, Suzuki H, Hamazaki T. Eicosapentaenoic acid inhibits antigen-presenting cell function of murine splenocytes. Immunology. 1992;75:330–335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakajima K, Yamashita T, Kita T, Takeda M, Sasaki N, Kasahara K, Shinohara M, Rikitake Y, Ishida T, Yokoyama M, Hirata K. Orally administered eicosapentaenoic acid induces rapid regression of atherosclerosis via modulating the phenotype of dendritic cells in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1963–1972. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.229443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Eliseo D, Velotti F. Omega-3 fatty acids and cancer cell cytotoxicity: implications for multi-targeted cancer therapy. J Clin Med. 2016;5:pii. doi: 10.3390/jcm5020015. E15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salameh A, Dhein S. Pharmacology of gap junctions. New pharmacological targets for treatment of arrhythmia, seizure and cancer? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1719:36–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsao YT, Kuo CY, Cheng SP, Lee CH. Downregulations of AKT/mTOR signaling pathway for Salmonella-mediated suppression of matrix metalloproteinases-9 expression in mouse tumor models. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1630. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson SJ, Andrews N, Ball D, Bellantuono I, Gray J, Hachoumi L, Holmes A, Latcham J, Petrie A, Potter P, Rice A, Ritchie A, Stewart M, Strepka C, Yeoman M, Chapman K. Does age matter? The impact of rodent age on study outcomes. Lab Anim. 2017;51:160–169. doi: 10.1177/0023677216653984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dutta S, Sengupta P. Men and mice: relating their ages. Life Sci. 2016;152:244–248. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang CJ, Chang WW, Lin ST, Chen MC, Lee CH. Salmonella overcomes drug resistance in tumor through P-glycoprotein downregulation. Int J Med Sci. 2018;15:574–579. doi: 10.7150/ijms.23285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qin Y, Han L, Yang D, Wei H, Liu Y, Xu J, Autrup H, Deng F, Guo X. Silver nanoparticles increase connexin43-mediated gap junctional intercellular communication in HaCaT cells through activation of reactive oxygen species and mitogen-activated protein kinase signal pathway. J Appl Toxicol. 2018;38:564–574. doi: 10.1002/jat.3563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato H, Iwata H, Takano Y, Yamada R, Okuzawa H, Nagashima Y, Yamaura K, Ueno K, Yano T. Enhanced effect of connexin 43 on cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity in mesothelioma cells. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009;110:466–475. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08327fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray M, Hraiki A, Bebawy M, Pazderka C, Rawling T. Anti-tumor activities of lipids and lipid analogues and their development as potential anticancer drugs. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;150:109–128. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao W, Ma Z, Rasenick MM, Yeh S, Yu J. N-3 poly-unsaturated fatty acids shift estrogen signaling to inhibit human breast cancer cell growth. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ceccarelli V, Valentini V, Ronchetti S, Cannarile L, Billi M, Riccardi C, Ottini L, Talesa VN, Grignani F, Vecchini A. Eicosapentaenoic acid induces DNA demethylation in carcinoma cells through a TET1-dependent mechanism. FASEB J; 2018. fj201800245R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LeMay-Nedjelski L, Mason-Ennis JK, Taibi A, Comelli EM, Thompson LU. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated fatty acids time-dependently reduce cell viability and oncogenic microRNA-21 expression in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells (MCF-7) Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:pii. doi: 10.3390/ijms19010244. E244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terada S, Takizawa M, Yamamoto S, Ezaki O, Itakura H, Akagawa KS. Suppressive mechanisms of EPA on human T cell proliferation. Microbiol Immunol. 2001;45:473–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2001.tb02647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]