Abstract

Angiogenesis is a critical aspect of wound healing. We investigated the role of keratinocytes in promoting angiogenesis in mice with lineage-specific deletion of the transcription factor FOXO1. The results indicate that keratinocyte-specific deletion of Foxo1 reduces VEGFA expression in mucosal and skin wounds and leads to reduced endothelial cell proliferation, reduced angiogenesis, and impaired re-epithelialization and granulation tissue formation. In vitro FOXO1 was needed for VEGFA transcription and expression. In a porcine dermal wound-healing model that closely resembles healing in humans, local application of a FOXO1 inhibitor reduced angiogenesis. This is the first report that FOXO1 directly regulates VEGFA expression and that FOXO1 is needed for normal angiogenesis during wound healing.

Keywords: angiogenesis, blood vessel, dermal, endothelial, mucosa, vascular endothelial growth factor-A, forkhead, FOXO, minipig, skin, wound, VEGF

Introduction

Angiogenesis is critical to wound healing and results from multiple signals acting on endothelial cells. The formation of new blood vessels during angiogenesis occurs by a budding or sprouting mechanism from intact vessels at the wound borders and requires endothelial cell proliferation. VEGFA is one of the most potent pro-angiogenic factors in healing wounds [1]. Major sources of VEGFA during wound healing are thought to be from cells in the connective tissue such as macrophages, fibroblasts, and mast cells [1]. VEGFA gene expression is induced by transcription factors including hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α. Genetic deletion of HIF-1α (Hif1a) in endothelial cells inhibits angiogenesis during tumor formation [2]. Global deletion of one allele of Hif1a reduces wound angiogenesis [3]. However, deletion of HIF-1α in myeloid cells has little effect on granulation tissue, raising the possibility that other cells are important in wound vascularization [4]. A better understanding of VEGFA regulation is a key to gaining further insight into wound angiogenesis.

Forkhead box O1 (FOXO1) is a forkhead transcription factor that participates in a wide range of cellular processes [5]. Global disruption of Foxo1 in mice causes lethal vascular remodeling defects [6]. FOXO1 is prominently activated in the leading edge and basal layer of keratinocytes after skin injury [5]. Lineage-specific Foxo1 deletion in keratinocytes interferes with keratinocyte migration and re-epithelialization in skin and mucosal wounds [5,7]. In this study, we investigated the role of FOXO1 in regulating VEGFA expression and angiogenesis in mice with keratinocyte-specific Foxo1 deletion and angiogenesis in a minipig model using a FOXO1 inhibitor.

Materials and methods

Additional details are provided in the supplementary material, Supplementary materials and methods.

Mouse experiments were approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and minipig experiments by the École Nationale Vétérinaire d’Alfort (ENVA, Maisons Alfort, France). Experimental (K14.Cre+.Foxo1L/L) and littermate control (K14.Cre−.Foxo1L/L) mice were generated by breeding transgenic (KRT14-cre+)1Amc/J (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and floxed Foxo1 mice [8]. Experiments were performed with adult mice 10–12 weeks old (four males and three females for D4 group/four males and four females for D7 group). Circular 1-mm diameter full-thickness mucosal wounds in the palatal gingiva (n = 7 per D4 and n = 8 per D7 group) or 2-mm diameter circular excisional wounds in the scalp (n = 3 per group) were created and mice were euthanized on days 4 and 7. Circular 1-cm diameter full-thickness dorsal wounds were created in minipigs (n = 5 per group, all females) to a minimal depth of 1 cm. The FOXO1 inhibitor AS1842856 (EMD Millpore, Billerica, MA, USA) was applied by microinjection (0.012 μmol/wound) on days 0, 2, 4, and 6, and tissue was collected on day 8 [9].

Histologic assessment

Specimens were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde [5] and assessed by Masson’s trichrome stain or by immunofluorescence with specific antibody versus control antibody.

In vitro studies

Human immortalized gingival keratinocytes (HIGKs) were cultured in KGM-2 growth medium supplemented with human keratinocyte growth supplements (Lonza, Allendale, NJ, USA) and maintained in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator at 37 °C [10]. RT-qPCR, chromatin immunoprecipitation assays (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA, USA), RNAi with FOXO1-specific or scrambled siRNA (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), quantitative immunofluorescence measuring mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), and VEGFA promoter activity with a luciferase reporter [11] were performed. Detailed methods are provided in the supplementary material, Supplementary materials and methods.

Results

Keratinocyte-specific Foxo1 deletion impairs angiogenesis during mucosal wound healing

Foxo1 expression was decreased in healing mucosal epithelium of experimental (K14.Cre+.Foxo1L/L) mice (supplementary material, Figure S1). Vascular density in wounds in Foxo1-deleted mice was decreased by 45–52% compared with control littermates (p < 0.05, Figure 1A). Keratinocyte-specific Foxo1 deletion significantly decreased the abundance of proliferating endothelial cells ~40–50%, as measured by Ki-67/CD31 double-positive cells (p < 0.05, Figure 1B). Wound closure was significantly reduced by Foxo1 deletion in keratinocytes (p < 0.05, Figure 1C). The gap between the wound edges was 1.5-fold larger in day 4 wounds of experimental K14.Cre+.Foxo1L/L mice compared with control littermates (p < 0.05, Figure 1C). On day 7, wounds in both groups had re-epithelialized. We reported previously that wound closure was impaired by the deletion of Foxo1 in keratinocytes in skin wounds [5]. Granulation tissue in experimental wounds was reduced on day 4 by 60% (p < 0.05) and on day 7 by 40% (p = 0.08) (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Keratinocyte-specific Foxo1 deletion in mucosal wounds reduces vascular density, endothelial cell proliferation, re-epithelialization, and granulation tissue formation. (A) CD31 immunofluorescence analyses in newly formed connective tissue (original magnification 400×, day 4). Bar = 50 μm. EPI, epithelium; CT, connective tissues. Vascular density in newly formed connective tissue was calculated as the number of CD31 immunopositive blood vessels/mm2. (B) Ki-67/CD31 double immunofluorescence (original magnification 400×, day 4). Bar = 50 μm. Quantification of Ki-67/CD31 double immunopositive cells for analyses of proliferating endothelial cells. (C) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections of K14.Cre−.Foxo1L/L and K14.Cre+.Foxo1L/L wounds (original magnification 100×, day 4). Bar = 100 μm. The epithelial gap (day 4). (D) The area with granulation tissue was measured in Masson’s trichrome-stained sections. Each in vivo value is the mean ±SEM for n = 7 mice per D4 group and n = 8 mice per D7 group. *p < 0.05 versus Cre− group;#p = 0.08 versus Cre− group.

Foxo1 regulates VEGFA

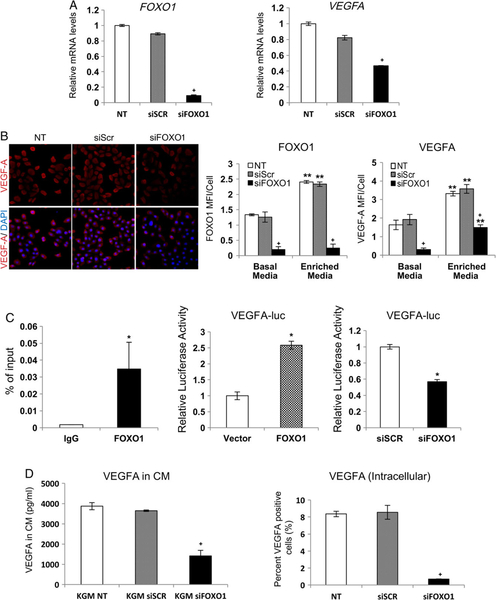

The levels of VEGFA expression were reduced in both mucosal and skin epithelium of experimental (K14.Cre+.Foxo1L/L) mice (Figure 2A and supplementary material, Figure S2). Keratinocyte-specific Foxo1 deletion significantly reduced VEGFA protein levels by 53% on day 4 (p < 0.05) and 42% on day 7 (p = 0.06) in wounded mucosal epithelium in vivo (Figure 2A). The combined level of VEGFA expression in epithelium and connective tissue of Foxo1-deleted mice was decreased by 43–48% compared with control littermates (p < 0.05, Figure 2B). Transfection of human gingival keratinocytes with FOXO1 siRNA significantly reduced VEGFA mRNA levels by 43% and protein levels by 57% (p < 0.05, Figure 3A, B). An analysis of the human VEGFA promoter region revealed a putative FOXO1 response element located between −798 and − 788 bp relative to the transcription start site. Based on this information, primers were selected for the ChIP amplicon between bp −896 and − 728 (supplementary material, Figure S3). Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays showed that endogenous FOXO1 is recruited to the VEGFA promoter (p < 0.05, Figure 3C). Overexpression of FOXO1 stimulated a 2.6-fold increase in VEGFA transcriptional activity, whereas FOXO1 silencing produced a 43% decrease (p < 0.05, Figure 3C). VEGFA released by keratinocytes transfected with FOXO1 siRNA or scrambled control siRNA was measured by ELISA. The levels of VEGFA in the conditioned medium were decreased by 55–60% by FOXO1 knockdown (p < 0.05, Figure 3D). Intracellular levels of VEGFA detected by ELISA were very low. As an alternative, we assessed intracellular VEGFA by flow cytometry. Knockdown of FOXO1 significantly reduced intracellular VEGFA levels in keratinocytes (p < 0.05, Figure 3D).

Figure 2.

Foxo1 deletion in keratinocytes reduces VEGFA expression in vivo. (A) VEGFA immunofluorescence in mucosal wounds (original magnification 400×, day 4). Bar = 50 μm. EPI, epithelium; CT, connective tissues. VEGFA mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) analysis in the epithelium on days 4 and 7. *p < 0.05 versus Cre− group;#p = 0.06 versus Cre− group. (B) VEGFA was assessed by immunofluorescence in the combined epithelium and connective tissue of healing wounds and measured as MFI. Each in vivo value is the mean ±SEM for n = 7 mice per D4 group and n = 8 mice per D7 group. *p < 0.05 versus Cre− group.

Figure 3.

FOXO1 deletion in keratinocytes reduces VEGFA expression in vitro. (A) HIGK cells were transfected with scrambled or FOXO1 siRNAs for 48 h. RT-qPCR analysis of FOXO1 and VEGFA mRNA levels. (B) VEGFA immunofluorescence in HIGK. FOXO1 and VEGFA MFI analysis.+p < 0.05 versus scrambled siRNA; **p < 0.05 versus basal media. (C) ChIP assays for the binding of FOXO1 to the VEGFA promoter. VEGFA-luciferase reporter gene analyses in HIGK; FOXO1 overexpression and FOXO1 silencing. *p < 0.05 versus vector or scrambled siRNA. (D) VEGFA released into keratinocyte conditioned media was measured by ELISA in cells transfected with scrambled or FOXO1 siRNA. The fraction of cells immunopositive for VEGFA in FOXO1- and scrambled-siRNA transfected cells as assessed using flow cytometry.+p < 0.05 versus scrambled siRNA. Each in vitro experiment was performed three times with similar results.

FOXO1 inhibitor reduces angiogenesis in the minipig skin wounds

Dermal wounds were examined at the center and edges, at a midpoint in the time course of healing. The FOXO1 inhibitor significantly reduced vascular density by 37% at the wound edge and 45% in the center (p < 0.05, Figure 4A, B).

Figure 4.

A FOXO1 inhibitor reduces vascular density in minipig skin wounds. CD31 immunofluorescence analyses (original magnification 400×). The FOXO1 inhibitor reduced vascular density on wound edges (A) and in the center area (B). EPI, epithelium; CT, connective tissue. Each in vivo value is the mean ±SEM for n = 5 minipigs per group. *p < 0.05 versus vehicle group. Bar = 50 μm.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that keratinocytes regulate angiogenesis in mucosal and skin wounds and that FOXO1 plays an essential role. ChIP assays indicated that FOXO1 interacts directly with the VEGFA promoter and our luciferase reporter assays indicated that overexpression of FOXO1 stimulates VEGFA transcript levels, and these are reduced by FOXO1 knockdown, supporting the direct regulation of VEGFA by FOXO1. Furthermore, deletion of Foxo1 in keratinocytes reduces re-epithelialization and granulation tissue formation. Local injection of a FOXO1 inhibitor in minipig skin wounds reduced angiogenesis.

While it is known that keratinocytes express VEGFA [12], the mechanism of its regulation during wound healing had not been fully clarified. In vivo and in vitro studies demonstrated that FOXO1 regulates VEGFA expression. We found that Foxo1 deletion in keratinocytes reduced keratinocyte-produced VEGFA and also reduced the total levels of VEGFA in healing wounds. Furthermore, the importance of FOXO1 is supported by reduced angiogenesis following application of a FOXO1 inhibitor to porcine skin wounds that heal similarly to those in humans [13]. That the murine and porcine wound healing models gave similar results supports the importance of keratinocytes in angiogenesis because the impact of Foxo1 deletion in keratinocytes was similar to that of local injection of a FOXO1 inhibitor.

In addition to its effect on keratinocytes, FOXO1 plays a direct role in vascular development and postnatal angiogenesis in endothelial cells [6,8,14,15]. While we show that FOXO1 is needed for VEGFA expression in keratinocytes, FOXO1 activation within vascular cells is also important [6,14]. Endothelial cell-specific deletion of FOXO1 causes hemangiomas resulting from excessive endothelial proliferation and reduced apoptosis [8,16]. In contrast, global or endothelial deletion of FOXO1 during development leads to embryonic lethality due to severe vascular defects [6]. Thus, FOXO1 in postnatal endothelial cells appears to suppress proliferation and permit apoptosis while it is needed in development for the formation of blood vessels. It has been suggested that the molecular signals regulating FOXO1 activity may be different between embryonic vascular development and postnatal vessel formation, and the downstream targets of FOXO1 may differ under these conditions [14]. This is consistent with our findings that the activity of FOXO1 in normal and diabetic healing differs because the microenvironment alters the pattern of genes induced by FOXO1 [7,17].

In our study, we found that FOXO1 deletion in keratinocytes led to impaired wound closure. It affects re-epithelialization in vivo and the capacity of keratinocytes to produce VEGFA in vivo and in vitro. VEGFA affects several components of the wound-healing cascade including angiogenesis, re-epithelialization, granulation tissue formation, and collagen deposition [18,19]. VEGFA can stimulate the migration and proliferation of a number of cell types including keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and myofibroblasts, an important component of wound healing [19,20]. Thus, the effect of VEGFA is likely to extend beyond stimulating angiogenesis during wound healing.

In summary, we found that keratinocyte-specific deletion of FOXO1 impaired wound angiogenesis and led to the reduced granulation tissue formation. This is the first evidence that FOXO1 organizes keratinocyte activity to promote VEGFA expression and wound angiogenesis. Application of a FOXO1 antagonist may be therapeutically useful where inhibition of angiogenesis would be beneficial, such as in end-stage diabetic retinopathy or tumor therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr RA DePinho for the floxed Foxo1 mice and Dr Keping Xie for the VEGFA reporter construct. We thank Dr. Faizan Alawi for help in the analysis of minipig histologic sections. We would also like to thank Eunice Han and Richa Pande for assistance with genotyping. This work was supported by a grant (R01DE019108; DTG) from the NIDCR and ITI grant #926–2013 (PGC).

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest were declare

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL ONLINE

Supplementary materials and methods

Figure S1. FOXO1 immunofluorescence demonstrating lineage-specific Foxo1 deletion in keratinocytes

Figure S2. VEGFA immunofluorescence in skin wounds

Figure S3. VEGFA promoter analysis identifies a putative FOXO1 response element

References

- 1.Nissen NN, Polverini PJ, Koch AE, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor mediates angiogenic activity during the proliferative phase of wound healing. Am J Pathol 1998; 152: 1445–1452. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang N, Wang L, Esko J, et al. Loss of HIF-1α in endothelial cells disrupts a hypoxia-driven VEGF autocrine loop necessary for tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 2004; 6: 485–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang X, Liu L, Wei X, et al. Impaired angiogenesis and mobilization of circulating angiogenic cells in HIF-1α heterozygous-null mice after burn wounding. Wound Repair Regen 2010; 18: 193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vural E, Berbee M, Acott A, et al. Skin graft take rates, granulation, and epithelialization: dependence on myeloid cell hypoxia-inducible factor 1α. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010; 136: 720–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ponugoti B, Xu F, Zhang C, et al. FOXO1 promotes wound healing through the up-regulation of TGF-β1 and prevention of oxidative stress. J Cell Biol 2013; 203: 327–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furuyama T, Kitayama K, Shimoda Y, et al. Abnormal angiogenesis in Foxo1 (Fkhr)-deficient mice. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 34741–34749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu F, Othman B, Lim J, et al. Foxo1 inhibits diabetic mucosal wound healing but enhances healing of normoglycemic wounds. Diabetes 2015; 64: 243–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paik JH, Kollipara R, Chu G, et al. FoxOs are lineage-restricted redundant tumor suppressors and regulate endothelial cell homeostasis. Cell 2007; 128: 309–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagashima T, Shigematsu N, Maruki R, et al. Discovery of novel forkhead box O1 inhibitors for treating type 2 diabetes: improvement of fasting glycemia in diabetic db/db mice. Mol Pharmacol 2010; 78: 961–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oda D, Bigler L, Lee P, et al. HPV immortalization of human oral epithelial cells: a model for carcinogenesis. Exp Cell Res 1996; 226: 164–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi Q, Le X, Abbruzzese JL, et al. Constitutive Sp1 activity is essential for differential constitutive expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 2001; 61: 4143–4154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown LF, Yeo KT, Berse B, et al. Expression of vascular permeability factor (vascular endothelial growth factor) by epidermal keratinocytes during wound healing. J Exp Med 1992; 176: 1375–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sullivan TP, Eaglstein WH, Davis SC, et al. The pig as a model for human wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 2001; 9: 66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Potente M, Urbich C, Sasaki K, et al. Involvement of Foxo transcription factors in angiogenesis and postnatal neovascularization. J Clin Invest 2005; 115: 2382–2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ren B, Best B, Ramakrishnan DP, et al. LPA/PKD-1–FoxO1 signaling axis mediates endothelial cell CD36 transcriptional repression and proangiogenic and proarteriogenic reprogramming. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2016; 36: 1197–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilhelm K, Happel K, Eelen G, et al. FOXO1 couples metabolic activity and growth state in the vascular endothelium. Nature 2016; 529: 216–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang C, Ponugoti B, Tian C, et al. FOXO1 differentially regulates both normal and diabetic wound healing. J Cell Biol 2015; 209: 289–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson KE, Wilgus TA. Vascular endothelial growth factor and angiogenesis in the regulation of cutaneous wound repair. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2014; 3: 647–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bao P, Kodra A, Tomic-Canic M, et al. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor in wound healing. J Surg Res 2009; 153: 347–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park HY, Kim JH, Park CK. VEGF induces TGF-β1 expression and myofibroblast transformation after glaucoma surgery. Am J Pathol 2013; 182: 2147–2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.