Abstract

Leaf rust caused by Puccinia triticina Eriks is one of the most problematic diseases of wheat throughout the world. The gene Lr42 confers effective resistance against leaf rust at both seedling and adult plant stages. Previous studies had reported Lr42 to be both recessive and dominant in hexaploid wheat; however, in diploid Aegilops tauschii (TA2450), we found Lr42 to be dominant by studying segregation in two independent F2 and their F2:3 populations. We further fine-mapped Lr42 in hexaploid wheat using a KS93U50/Morocco F5 recombinant inbred line (RIL) population to a 3.7 cM genetic interval flanked by markers TC387992 and WMC432. The 3.7 cM Lr42 region physically corresponds to a 3.16 Mb genomic region on chromosome 1DS based on the Chinese Spring reference genome (RefSeq v.1.1) and a 3.5 Mb genomic interval on chromosome 1 in the Ae. tauschii reference genome. This region includes nine nucleotide-binding domain leucine-rich repeat (NLR) genes in wheat and seven in Ae. tauschii, respectively, and these are the likely candidates for Lr42. Furthermore, we developed two kompetitive allele-specific polymorphism (KASP) markers (SNP113325 and TC387992) flanking Lr42 to facilitate marker-assisted selection for rust resistance in wheat breeding programs.

Keywords: wheat, Aegilops tauschii, Lr42, disease resistance, molecular mapping, KASP markers, marker-assisted selection

1. Introduction

Wheat is one of the leading staple foods worldwide, providing one-fifth of the calories and protein to more than 4.5 billion people [1]. Wheat production is constrained not only due to changing climate, but to a great extent by the emergence of new and more virulent races of economically important pathogens. Several diseases and insect pests, including leaf rust (caused by Puccinia triticina Eriks), threaten sustainable wheat production in the major wheat-growing areas of the world [2]. In Kansas alone, the leaf rust epidemic of 2007 caused yield losses of 13.9% in winter wheat [3]. Yield losses are attributed to fewer kernels, aggregated by lower kernel weight [2], and losses can be severe if wheat is infected early in development and may reach epidemic proportions in susceptible cultivars under favorable conditions [4]. Diving into history, one can find a reference to leaf rust in the Bible and literature of classical Greece and Rome [5]. Also, the existence of prevalence of this disease from that era until today indicates that this pathogen has evolved along with wheat or other grass species and there has been no permanent solution to control this disease, and likewise for other rusts.

Breeding for rust resistance is considered as one of the most economical approaches to manage rust diseases, and wheat breeding programs throughout the world are deploying rust resistance genes in commercial cultivars. The populations of P. triticina are reported to be highly variable in North America [6], with many different virulence pathotypes or races detected annually. Therefore, a more durable approach for long-lasting resistance is the pyramiding of different race-specific and race non-specific genes in single cultivars [7]. However, combining different resistance genes using phenotypic selection is a challenging and cumbersome process. Molecular markers can be very useful for simultaneous stacking of different resistance genes. Thus, the availability of tightly linked molecular markers for different genes is essential for facilitating the stacking of these genes into a single genetic background.

To date, around 80 leaf rust resistance (Lr) genes have been formally reported in wheat and its wild relatives [8]. Aegilops tauschii Coss, the D-genome donor of wheat, has been a rich source of resistance genes [9,10] and agronomic traits [11]. Several leaf rust resistance genes (Lr21 (1D), Lr32 (3D), Lr39 (2D)) have been transferred into bread wheat from Ae. tauschii, including Lr42 [12]. Lr42 was introgressed into wheat through a direct cross with Ae. tauschii (accession TA 2450) and released as KS91WGRC11 (Century*/TA2450) for further utilization in hexaploid wheat breeding. KS91WGRC11 (carrying Lr42) has been successfully used by breeders in several breeding programs [13,14]. Studying near-isogenic lines (NILs) for the Lr42, Martin et al. [15] reported that Lr42 plays an important role in increasing yield, test weight, and kernel weight in wheat. Lr42 still is one of the highly effective genes, conferring resistance at both seedling and adult plant stages and being used in CIMMYT lines for breeding against leaf rust.

Cox et al. [16] first reported Lr42 on chromosome 1DS using monosomic analysis in wheat, and it was found to be closely linked to Lr21. In their study, Cox et al. [16] reported Lr42 to be a partially dominant race-specific gene. However, Czembor et al. [17] used Diversity Arrays Technology (DArT) markers to map Lr42 gene on chromosome 3D and reported that Lr42 behaved as a dominant gene. By analyzing a set of near-isogenic lines (NILs), Sun et al. [18] mapped Lr42 on the distal end of chromosome arm 1DS by employing simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers. Using a segregating population of NILs (for Lr42) and evaluating for rust infection at both seedling and adult plant stages, they identified three molecular markers—WMC432, CFD15, and GDM33—closely linked to Lr42. WMC432, about 0.8 cM from Lr42, was found to be the closest marker; however, no flanking markers were reported. Further, Liu et al. [19] analyzed an F2 population derived from a cross of KS93U50 (Lr42)/Morocco to map Lr42 on chromosome 1DS using six SSR loci with the quantitative calculation method and reported Lr42 as a recessive gene. Lr42 was flanked by WMC432 and GDM33 onto a 17 cM region at the distil end of chromosome 1DS with the closest proximal marker (WMC432) around 4 cM away. Although the previous studies were able to map Lr42 to wheat chromosome 1DS, the gene lies in a very gene-rich and recombination-hotspot region at the terminal tip of wheat chromosome 1DS; therefore, SSR markers flanking 17 cM regions are not suitable for marker-assisted selection.

The objectives of this study were to (1) determine the genetic and physical location of Lr42 on the chromosome 1D and (2) develop kompetitive allele-specific polymorphism (KASP) markers to facilitate marker-assisted selection of Lr42 in wheat breeding programs. This work will lay the foundation for further cloning of the gene.

2. Results

2.1. Genetic Analysis of Lr42 in Ae. tauschii

The parental lines TA2433 and TA10132 (AL8/78) showed a highly susceptible response to the leaf rust isolate PNMRJ, with an infection type (IT) score of 3, whereas the Lr42-carrying accession TA2450 showed highly resistant response with an IT score. Of the 66 F2 plants screened from the TA2450/TA2433 population, 50 were resistant and 16 were susceptible, fitting a 3:1 ratio (χ2 = 0.20, p = 0.89) for a single dominant gene (Lr42) segregation in this population (Table 1). Further, the 100 F2:3 families also exhibited a good fit for the expected 1:2:1 (resistant:segregating:susceptible) ratio (χ2 = 1.92, p = 0.38).

Table 1.

Segregation of Lr42 in Ae. tauschii and hexaploid wheat populations against leaf rust race PNMRJ. The observed and expected ratios correspond to the resistance:susceptible in F2 generations and homozygous resistant:segregating:homozygous susceptible in F2:3 generations.

| Sr No. | Species | Population | Generation | Lines Evaluated | Observed Ratio | Expected Ratio | χ2 | p-Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ae. tauschii | TA2450/TA2433 | F2 | 66 | 50:16 | 3:1 | 0.20 | 0.89 |

| F2:3 | 100 | 27:54:19 | 1:2:1 | 1.92 | 0.38 | |||

| 2 | Ae. tauschii | TA2450/TA10132 (AL8/78) | F2 | 67 | 53:14 | 3:1 | 0.60 | 0.44 |

| F2:3 | 100 | 33:53:14 | 1:2:1 | 7.58 | 0.02 | |||

| 3 | T. aestivum | KS93U50/Morocco | F5 RIL | 234 | 99:135 | 1:1 | 5.54 | 0.02 |

* α = 0.01.

The second F2 population derived from the cross TA2450/TA10132 showed 53 resistant and 14 susceptible individuals, fitting a 3:1 ratio (χ2 = 0.60, p = 0.44) and confirming that Lr42 behaves as a dominant gene (Table 1). Similarly, 100 F2:3 families (TA2450/TA10132) evaluated also fit the 1:2:1 (resistant:segregating:susceptible) ratio (χ2 = 7.58, p = 0.02), with skewing toward resistant families. Our results from segregation of resistance and susceptibility in these two populations suggest that Lr42 shows dominant inheritance in Ae. tauschii backgrounds.

2.2. Phenotypic Evaluation of KS93U50/Morocco RIL Population

The hexaploid wheat line KS93U50 carrying Lr42 showed resistance reaction against isolate PNMRJ producing an infection type (IT) score of 2, whereas Morocco, the susceptible parent of the RIL population, exhibited an IT score of 3+ as expected. The individual plants of 234 F5 RILs from the KS93U50/Morocco population were evaluated for responses to PNMRJ and 99 RILs were found to be rust-susceptible, while the other 135 RILs showed a resistant response. The 1S:1R segregation ratio (χ2 = 5.54) suggests the presence of a single resistance gene Lr42 in the RIL population (Table 1).

2.3. Marker Discovery and Molecular Mapping

Numerous genomic resources were employed to develop new markers to saturate the target Lr42 region. The flanking markers for Lr42, namely GDM33, WMC432, and CFD15 [19], were amplified from Chinese Spring (CS) chromosomes 1D, 4D, and 6D bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) pools. These pools were developed from a BAC library contructed from fraction-I chromosomes (1D, 4D, and 6D) obtained through flow cytometry separation of CS DNA. CFD15 was physically mapped to two BAC clones (146DhC878D17 and 146DhC799I02), whereas WMC432 was mapped to four BAC clones (146DhB488K16, 146DhC808O03, 146DhB488K16, and 146DhB458C07). Both these markers were mapped to the single BAC contig ctg1768; however, the distal marker GWM33 could not be mapped to a unique BAC contig. Our BAC-based physical map of CS chromosome 1D is anchored to Ae. tauschii 10K Infinium SNP-based genetic maps, and we identified BAC contigs proximal and distal to ctg1768 in a 1D physical map (https://urgi.versailles.inra.fr/gb2/gbrowse/wheat_phys_1D_v1/). Six BAC contigs were identified spanning this very terminal region of chromosome 1DS. The 24 BACs in these six contigs were end-sequenced to identify five new SSR markers.

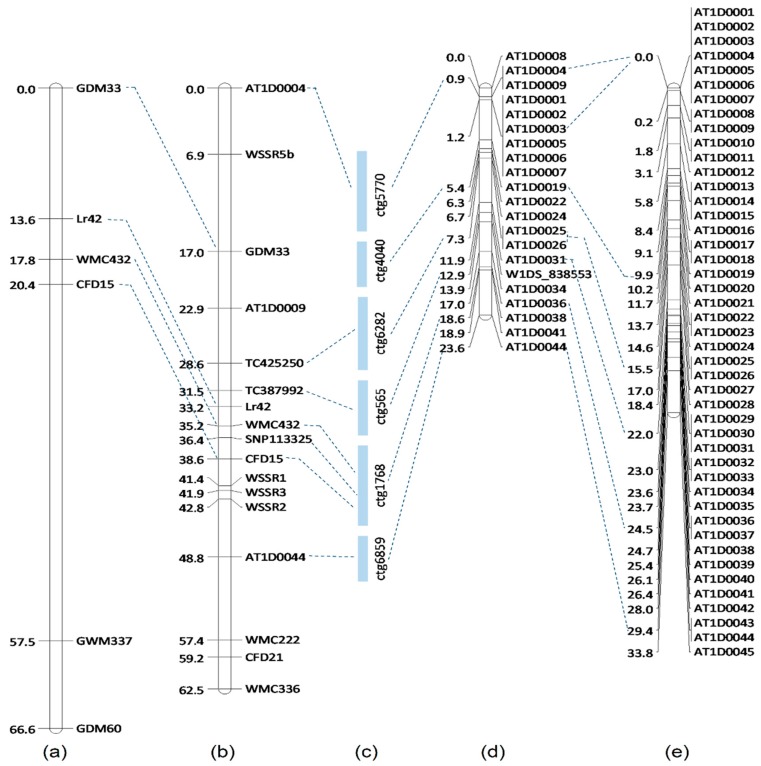

We further employed comparative genomic analysis with chromosome 1H of barley [20] for the development of new molecular markers. The collinear interval on chromosome 1H was determined, and 24 genes were predicted to carry plant defense-related domains. Wheat expressed sequence tag (EST) sequences collinear to barley genes were used to develop 19 new EST markers for saturation of the Lr42 region. In addition, we identified 44 SNPs from Ae. tauschii 10K Infinium SNPs mapped on the terminal end of chromosome 1D in a Prelude (TA2988)/synthetic wheat (TA8051) RIL population (Figure 1) and also in an Ae. tauschii AL8/78 (TA10132)/AS75 F2 population [21]. These SNPs were anchored on a CS 1D physical map. Thus, a total of five SSR markers, 19 EST markers, and 44 KASP markers were designed to enrich the candidate region. Of the 68 markers, 11 were polymorphic between KS93U50 and Morocco and used for mapping of Lr42 (Figure 1, Table 2). We were able to narrow Lr42 to a 3.7 cM interval flanked by markers TC387992 and WMC432 as against the previously reported 17 cM interval on the terminal end of the short arm of chromosome 1D in wheat (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparative genetic and physical map of the leaf rust resistance gene Lr42: (a) genetic map in a KS93U50/Morocco F2 population [21]; (b) genetic map in a KS93U50/Morocco F5 recombinant inbred line (RIL) population (current study); (c) physical mapping of the Lr42 region on Chinese Spring 1D bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) contigs (current study), and (d) Prelude (TA2988)/synthetic wheat (TA8051) RIL population (current study), and (e) an Ae. tauschii AL8/78 (TA10132)/AS75 F2 population [19].

Table 2.

Simple sequence repeat (SSR) and KASP markers developed and mapped on the KS93U50/Morocco RIL population.

| Sr. No. | Primer Name | Assay Type | Sequence(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | WSSR1 | SSR | ACGACGTTGTAAAACGACTGGAGACAGACGAACGCATA |

| TGCATGCATACACACACCAG | |||

| 2 | WSSR2 | SSR | ACGACGTTGTAAAACGACAGCAATGCAGTTGCAAAGAG |

| GCAAAGATGGACAGATGGCT | |||

| 3 | WSSR3 | SSR | ACGACGTTGTAAAACGACAAGATCAGCTCCGACAGCTC |

| CGAAGTCAGCACAAACCAAA | |||

| 4 | WSSR5 | SSR | ACGACGTTGTAAAACGACTGGTGAATCTTGCACCACAT |

| CTGGACACCGTTCGTTAGGT | |||

| 5 | AT1D004 | KASP | GGTACCATGTTGTTTCGCATGTCTAT |

| GTACCATGTTGTTTCGCATGTCTAC | |||

| GGAGGCAGAGACAATAAGTTTATGTTACAA | |||

| 6 | AT1D0009 | KASP | GGAGATCTTTATATTTGTGGTTTGCCA |

| GAGATCTTTATATTTGTGGTTTGCCG | |||

| CCAGGTCACAGGCTGTGATGTTTAA | |||

| 7 | TC425250 | KASP | GCACTACTTTTATTGATGTTGTGTAACC |

| AAGCACTACTTTTATTGATGTTGTGTAACT | |||

| CAGAGGGAAGAAAACAACACTGAACAAAA | |||

| 8 | TC387992 | KASP | TTGGATCTGCATTCCTTCTCCCA |

| GGATCTGCATTCCTTCTCCCG | |||

| CTTTGGGATGTTGCTGCTGGAGAT | |||

| 9 | SNP113325 | KASP | GGTGTTTGGCAGCATCATCACG |

| GGTGTTTGGCAGCATCATCACC | |||

| GACAACTTGAGACACTAGATATCAGAGAT |

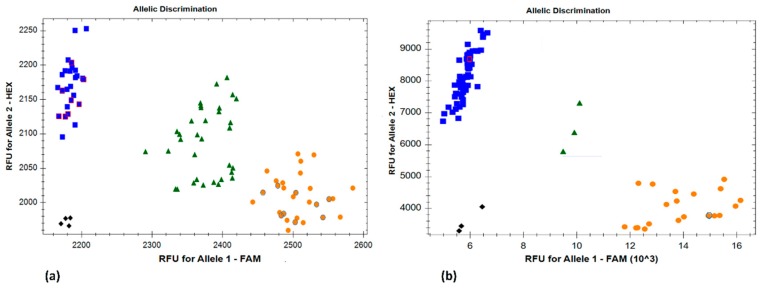

Further, an additional KASP marker, SNP113325, developed from comparative analysis with barley, was mapped 3.2 cM proximal to Lr42, but physically mapped to the same BAC contig as WMC432 and CFD15. The two KASP markers, SNP113325 and TC387992, could be very useful in marker-assisted selection for Lr42 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kompetitive allele-specific polymorphism (KASP) marker SNP113325 identifying the resistant and susceptible parents and selected progenies of (a) an Ae. tauschii (TA2450/TA2433) F2 population; (b) a hexaploid wheat (KS93U50/Morocco) F5 RIL population. Blue: susceptible homozygotes; green: heterozygotes; orange: resistant homozygotes; black: non-template controls. The parental resistant (orange with a blue border) and susceptible (blue with a red border) lines have been highlighted in the respective figures.

2.4. Candidate Genes in the Lr42 Region in Wheat and Ae. tauschii

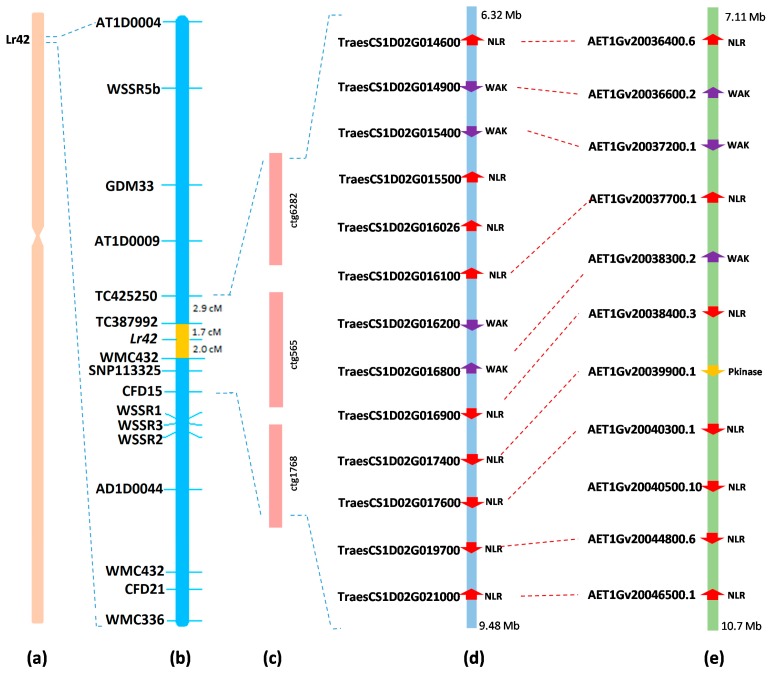

The flanking markers (TC42520 and CFD15) and BAC end sequences from the region flanking Lr42 were BLASTN searched against CS Wheat RefSeq v1.1 [22]. We identified a corresponding physical segment of 3.16 Mb (6,327,249 bp to 9,490,443 bp) on the tip of the short arm of chromosome 1D of CS Wheat. On the other hand, we identified a 3.5 Mb syntenic Lr42 region in Ae. tauschii chromosome 1. There are 109 high-confidence genes in the 3.16 Mb Lr42 region based on CS Wheat RefSeq v1.1, of which 23 genes were associated with disease resistance function and three were annotated as serine/threonine protein kinase genes (Table S1). Among the 23 disease resistance genes, 19 genes had NLR domains (associated with most of the rust resistance genes cloned in wheat to date) and another four genes had wall-associated kinase (WAK) domains. Further analysis of these 19 NLR genes showed that 10 genes carry pseudo-NLRs (Table S2); therefore, only nine carry functional NLR domains in the Lr42 region (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Candidate genes in the Lr42 region in wheat and Ae. tauschii. (a) Physical location of Lr42 on chromosome 1DS of wheat; (b) genetic location of Lr42 in KS93U50/Morocco F5 RIL; (c) BAC contigs spanning the Lr42 physical region; (d) annotated genes in the Lr42 region in CS RefSeq v1.1 [22]; (e) annotated genes in the Lr42 region in the Ae. tauschii chromosome 1 sequence [21]. NLR: nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeats; WAK: wall-associated kinase; Pkinase: protein kinase.

In Ae. tauschii, we identified 98 genes in the 3.5 Mb Lr42 region, with 21 genes encoding plant disease defense-related proteins (Table S3), using the PFAM database [23]. Among the 21 genes, three have putative wall-associated kinase (WAK) domains, seven genes had serine/threonine protein kinase (Pkinase) domains, and 11 genes had NB-ARC domains (Figure 3). Comparative analysis of wheat and Ae. tauschii genes in the Lr42 region showed that four of the 11 NLR genes in Ae. tauschii are orthologues of pseudo-NLRs in wheat. Furthermore, the comparison of genes from two species showed that six NLRs and two WAKs from wheat have high sequence similarity (>96%) and are orthologues in Ae. tauschii. One NLR gene from wheat could be an orthologue of a protein kinase (Pkinase) gene from Ae. tauschii as it shared a sequence similarity of 90%. Apart from these genes, no orthologues were found in Ae. tauschii for one WAK and two NLR genes that were present in wheat. By contrast, one NLR gene was present in Ae. tauschii but absent in wheat (Figure 3).

3. Discussion

Leaf rust can cause severe losses in wheat yield and grain quality. Host resistance is a key component in managing leaf rust, and thus, molecular genetic characterization of resistance and identification of tightly linked molecular markers can help achieve better understanding of the mechanism of leaf rust resistance and facilitate marker-assisted breeding and gene pyramiding. Liu et al. [19] mapped Lr42 on the short arm of wheat chromosome 1D after analyzing F2 and F3 generations of KS93U50/Morocco population. In the current study, we advanced the population to F5 RILs. Segregation observed in F2 and F3 generations of the KS93U50/Morocco population as studied by Liu et al. [19] suggested that Lr42 was recessive. In the current study, we evaluated two independent Ae. tauschii F2 populations (TA2450/TA2433 and TA2450/TA10132) for a response to leaf rust using the same isolate, PNMRJ. In both the populations, the majority of plants were resistant, indicating a dominant monogenic control of the resistance reaction. Further segregation pattern in the F2:3 generation in the two Ae. tauschii populations was consistent with F2, suggesting that Lr42 behaves as a dominant gene in Ae. tauschii. Ae. tauschii (the D-genome donor of wheat) is the source of Lr42, however, the segregation behavior of Lr42 had not been studied earlier in Ae. tauschii. There are several conflicting reports regarding the segregation behavior of the Lr42 gene in hexaploid wheat. Cox et al. [16] reported that Lr42 was partially dominant, whereas Czembor et al. [17] reported it as being a dominant gene in wheat. However, these studies used several different genetic backgrounds or different leaf rust isolates, which could have resulted in the differences, as demonstrated by Kolmer and Dyck [24].

Applying BAC-based physical mapping, BAC-end sequencing, and comparative genomic analysis with barley [20], we identified 68 new markers and further mapped Lr42 to a 3.7 cM interval. Liu et al. [19] reported Lr42 as being located on the distal tip of chromosome 1DS flanked by a 17 cM interval. In the current study, we significantly reduced the size of the Lr42 flanking segment by mapping TC387792 and WMC432, as being 1.7 cM and 2.0 cM away from Lr42 on the distal and proximal regions, respectively. Additionally, SNP113325 lies 3.2 cM distal to Lr42 and is also tightly linked to Lr42 in the RIL population. The two KASP markers SNP113325 and TC387792 have been used for screening of hard winter wheat in regional nurseries (see 2018 SRPN, Table 10 from https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/30421000/HardWinterWheatRegionalNurseryProgram/2018%20SRPN%20021519.xlsx) in marker-assisted selection for Lr42 in wheat breeding programs.

We further physically delimited the Lr42 region to a 3.16 Mb (6,327,249 bp to 9,490,443 bp) region in chromosome 1D using the Chinese Spring reference genome RefSeq v1.1 [22]. As expected, Lr42 is present in a high-recombination region with a higher genetic-to-physical map ratio, making the search for the candidate gene relatively easy compared to the centromeric region. Though we identified 109 genes in this region, 23 of these genes have kinase domains mostly associated with disease-related genes in wheat. Besides the 23 genes, three genes were annotated as protein kinases (Pkinases); however, Pkinase genes have not been associated with wheat rust resistance genes to date. Out of the 23 genes, 10 genes were found to be pseudo-NLRs, leaving only 13 candidate genes. Of the final 13 candidate genes, nine genes have NLR domains and four genes have WAK domains. In Ae. tauschii, we identified seven genes with NLR domains that could be candidates for Lr42. Currently, several rust resistance genes have been cloned in wheat, including Lr10 [25], Lr21 [26], Lr1 [27], Lr22a [28], Sr33 [29], Sr35 [30], Sr45 [31], and Yr10 [32], and all encode an NLR-type protein. Though wall-associated kinase domains (WAKs) have been reported to confer resistance to fungi in wheat, such as Snn1 against Septoria nodorum blotch [33] and Stb6 against Septoria tritici blotch [34], none of them showed resistance to wheat rusts. Therefore, the nine NLR-type genes in the Lr42 region are the most probable candidates for the Lr42 gene. Nonetheless, it is possible that Lr42 has a regulatory mechanism different from NBS-LRR type genes. Molecular cloning of Lr42 is thus required to reveal the complete regulation mechanism, which can be facilitated using novel cloning techniques such as MutRenSeq [31] or TACCA [28]. These techniques have been recently used to clone several disease-related genes in wheat, such as Lr22a [28] and Pm2 [35]. Thus, we have identified an Lr42 susceptible mutant by EMS mutagenesis of Ae. tauschii accession TA2450, and future efforts will be made to further characterize Lr42.

Lr42 is physically located on the distal region of wheat chromosome 1DS, where a number of disease-related genes have been mapped to, such as Lr21 [26], Sr33 [29], Sr45 [31], Pm24 [36], and several other genes of agronomic importance. In wheat, the terminal gene-rich regions have been found to be positively correlated with recombination frequency [37]. Identification of tightly linked flanking markers could facilitate marker-assisted selection of Lr42 in wheat breeding programs. The KASP markers developed in our study closely flank Lr42 and could be efficiently used for marker-assisted selection of Lr42 and help in stacking of the Lr42 gene with other race non-specific disease resistance genes to develop wheat cultivars with more durable resistance against leaf rust.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Rust Resistance Evaluation

Lr42 was identified from Ae. tauschii accession TA2450 [16]. We screened several Ae. tauschii accessions with leaf rust race PNMRJ and identified two Ae. tauschii accessions, TA2433, and TA10132 (AL8/78), that were susceptible to PNMRJ (PNMRJ is avirulent to Lr42). TA2450 was then crossed to TA2433 and TA10132 to develop two F2 populations (TA2450/TA2433 and TA2450/TA10132). A total of 100 F2 plants were derived from each cross (TA2450/TA2433 and TA2450/TA10132), of which a sample of around 70 plants were artificially inoculated with leaf rust race PNMRJ in a greenhouse following the method described by Liu et al. [19]. Briefly, the F2 plants from each of the two crosses, along with the parental lines, were planted in plastic trays. The plants were artificially inoculated with PNMRJ at the two-leaf stage. For artificial inoculation, the PNMRJ spores were suspended in Soltrol 170 mineral oil (CPChemicals LLC, Garland, TX, USA). The suspension was sprayed on the seedlings using a pressure sprayer, followed by incubation at 20 °C for 24 h in a humid chamber. Following incubation, the F2 plants were grown in a greenhouse at 20–24 °C for the establishment of infection. At ten days after inoculation, the seedlings were scored for rust infection type (IT) on a 1 to 4 scale (; = hypersensitive flecks, 1 = small uredinia with necrosis, 2 = moderate size pustules with chlorosis, 3 = moderate-large size uredinia without necrosis or chlorosis, and 4 = large uredinia lacking necrosis or chlorosis) [38,39]. The scoring was repeated after two days for confirmation. For further study, F2:3 progenies for each cross were grown and evaluated for leaf rust to identify homozygous non-segregating families. About 20 seeds for each family were grown and evaluated using the same procedure used for the F2 populations. Based on the reactions of parental lines to PNMRJ, the plants with IT ≤ 2 were considered resistant and those with IT > 2 susceptible.

In addition to the two Ae. tauschii populations, we used the F5 RIL population of 234 progenies developed from the wheat cross KS93U50/Morocco. The RIL population, along with parents KS93U50 and Morocco, were grown and evaluated for leaf rust resistance under controlled greenhouse conditions with three replications. The F5 RILs were advanced lines from the F2 population analyzed by Liu et al. [19] to map Lr42. The inoculation and scoring method was the same as described for Ae. tauschii populations. The data from the three populations were used to deduce the inheritance pattern of Lr42.

4.2. Marker Discovery and Saturation in the Candidate Region

Previously reported Lr42 flanking markers [19] were mapped on to the physical map of chromosome 1D of Chinese Spring wheat (https://urgi.versailles.inra.fr/gb2/gbrowse/wheat_phys_1D_v1/) by identifying the BACs associated with the candidate region using three-dimensional BAC pools. Identified BACs spanning this region were end-sequenced to generate five new PCR-based SSR markers using the DesignPrimer tool (https://kofler.or.at/bioinformatics/SciRoKo/DesignPrimer.html). Further, the genomic information from the BACs and comparative analysis with chromosome 1H of barley [20] was conducted to develop an additional 19 EST markers. In addition, KASP markers were developed from Ae. tauschii 10K Infinium single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [19] that were mapped onto the BACs of this region. A total of 68 new molecular markers, along with previously reported markers, were used to genotype the F5 RILs along with the parents. The polymorphic markers were used for the construction of a genetic map for the Lr42 region. The EST markers that were polymorphic between parents were later converted into KASP-based markers for easy and reliable genotyping and to select Lr42 in breeding programs.

4.3. DNA Extraction and Genotyping of the RIL Population

Ten-day-old uninfected seedlings of RILs, along with parental lines, were used for DNA extraction using the cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) method [40]. Extracted DNA samples were quantified using a Nanodrop ND1000 spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies, US) for normalization of DNA concentration. For SSR and EST genotyping, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was carried out in a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA) using 20 µL of reaction mixture containing 100 ng genomic DNA, 25 ng each of forward and reverse primers, and 10 µL of 2× PCR Mastermix. Thermocycling profile was set as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; 30 cycles each at 95 °C for 30 sec, 50–61 °C (depending upon the annealing temperature of particular primers) for 30 sec, 72 °C for 1 min; and a final extension step at 72 °C for 7 min. The EST and SSR PCR products were visualized using 3% high-resolution agarose gel (GeneMate, ISC Bioexpress, Inc, Kaysville, UT, USA). The kompetitive allele-specific polymorphism (KASP) genotyping was carried out using 8 µL of total reaction mixture containing 3 µL of 20–25 ng/µL genomic DNA, 5 µL of KASP Mastermix (LGC Genomics, Teddington, UK) consisting of a FAM and HEX specific FRET cassette, Taq polymerase and optimized buffer; and 0.07 µL of KASP assay mix consisting of two allele-specific primers and one common primer. For accurate distribution of the small volume of assay mix, KASP Mastermix and assay mix were combined before dispensing. PCR was carried out using a Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The PCR profile was designed as follows: 94 °C for 20 min (hot start activation); 10 touchdown cycles each at 94 °C for 20 sec, 61–55 °C for 60 sec (dropping by 0.6 °C per cycle); followed by 35 cycles at 94 °C for 20 sec and 55 °C for 60 sec. Bio-Rad CFX Manager (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA) was used for reading the plates after PCR.

4.4. Statistical Analysis and Genetic Mapping

Pearson’s chi-squared analysis was used to test the goodness of fit for observed frequencies to the expected genetic frequencies. The chi-squared analysis was performed in R ver 3.4 [41] using the function ‘chisq.test’. CarthaGene v1.3 was employed for the construction of genetic maps and automatical marker ordering to obtain a multipoint maximum likelihood map [42]. Firstly, a logarithm of odds (LOD) score of 3.0 was used as a threshold value for identifying the linkage groups, followed by ordering of the markers using the Kosambi mapping function [43]. The genetic linkage map was improved using the ‘simulated annealing’ algorithm and ‘verification algorithms’ in Carthagene [42]. MapChart version 2.2 [44] was used to draw and combine different genetic maps.

4.5. Physical Mapping of the Lr42 Region on Chromosome 1DS

Using BAC-end sequences and the sequences of EST markers flanking Lr42, we identified the Lr42 region in the hexaploid wheat Chinese Spring (CS) chromosome 1D RefSeq v1.1 [22] and the Ae. tauschii reference genome sequence [45] using BLASTN [46]. Gene annotation of the Lr42 genomic interval on CS chromosome 1D of wheat [22] and Ae. tauschii chromosome 1 [45] was obtained to identify candidate disease-resistance genes in the region.

5. Conclusions

In the current study, we fine-mapped the leaf rust resistance gene Lr42 to a 3.7 cM region from the previously reported 17 cM region on chromosome 1DS in wheat. We further physically mapped the Lr42 region on Chinese Spring RefSeq v1.1 and Ae. tauschii reference genomes and identified genes with defense-related functions as possible candidates for Lr42. The KASP markers flanking Lr42 developed in the current study will facilitate marker-assisted selection of Lr42 and pyramiding of the gene with other adult plant resistance genes for effective management of leaf rust in wheat.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the South Dakota Agriculture Experimental Station (Brookings, SD, USA) and Kansas State University Agriculture Experimental Station (Manhattan KS) for providing the resources to conduct the experiments.

Abbreviations

| MAS | Marker-assisted selection |

| KASP | Kompetitive allele-specific PCR |

| BAC | Bacterial artificial chromosome |

| EST | Expressed sequence tag |

| SSR | Simple sequence repeat |

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be found at https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/20/10/2445/s1.

Author Contributions

S.K.S. and B.S.G. conceptualized the experiment and designed the methodology; S.K.S., H.S.G., and J.S.S. performed data curation and formal analysis; C.L., D.W., H.S.G., J.S.S., W.L., and S.K.S. performed the investigation; G.B., D.W., and S.K.S. developed the mapping populations; H.S.G. and S.K.S. performed the software analysis; S.K.S. supervised the experiment; H.S.G. and S.K.S. wrote the original manuscript; B.S.G., G.B., D.W., W.L., and J.S.S. contributed to the interpretation of results and revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript.

Funding

This project was collectively funded by the USDA hatch projects SD00H538-15 and the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grants 2011-68002-30029 (Triticeae-CAP), 2017-67007-25939 (Wheat-CAP) and 2019-67013-29015 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture and South Dakota Wheat Commission grant 3X9267. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Shiferaw B., Smale M., Braun H.J., Duveiller E., Reynolds M., Muricho G. Crops that feed the world 10. Past successes and future challenges to the role played by wheat in global food security. Food Sec. 2013;5:291–317. doi: 10.1007/s12571-013-0263-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolton M.D., Kolmer J.A., Garvin D.F. Wheat Leaf Rust Caused by Puccinia Triticina. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2008;9:563–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2008.00487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appel J.A., Dewolf E., Todd T., Bockus W.W. Preliminary 2015 Kansas Wheat Disease Loss Estimates. Kansas Department of Agriculture; Manhattan, KS, USA: 2015. [(accessed on 18 March 2019)]. Kansas Cooperative Plant Disease Survey Report. Available online: http://agriculture.ks.gov/docs/default-source/PP-Disease-Reports-2014/2014-ks-wheat-disease-loss-estimates.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marasas C.N., Melinda S., Singh R.P. The Economic Impact in Developing Countries of Leaf Rust Resistance Breeding in CIMMYT-Related Spring Bread Wheat. CIMMYT (International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center); Texcoco, Mexico: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chester K.S. The Nature and Prevention of the Cereal Rusts as Exemplified in the Leaf Rust of Wheat. Chronica Botanica Company; Walthan, MA, USA: 1946. p. 269. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolmer J.A., Hughes M.E. Physiologic Specialization of Puccinia Triticina on Wheat in the United States in 2012. Plant Dis. 2014;98:1145–1150. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-12-13-1267-SR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolmer J.A., Chen X., Jin Y. Diseases Which Challenge Global Wheat Production the Wheat Rusts. In: Carver B.F., editor. Wheat: Science and Trade. Wiley-Blackwell; Ames, IA, USA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qureshi N., Bariana H., Kumran V.V., Muruga S., Forrest K.L., Hayden M.J., Bansal U. A New Leaf Rust Resistance Gene Lr79 Mapped in Chromosome 3BL from the Durum Wheat Landrace Aus26582. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2018;131:1091–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00122-018-3060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gill B.S., Raupp W.J., Sharma H.C., Browder L.E., Hatchett J.H., Harvey T.L., Moseman J.G., Waines J.G. Resistance in Aegilops Squarrosa to Wheat Leaf Rust, Wheat Powdery Mildew, Greenbug, and Hessian Fly. Plant Dis. 1986;70:553–556. doi: 10.1094/PD-70-553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhaliwal H.S., Singh H., Gupta S., Bagga P.S., Gill K.S. Evaluation of Aegilops and wild Triticum species for resistance to leaf rust (Puccinia recondita f. Sp. Tritici) of Wheat. Int. J. Trop. Agric. 1991;9:118–122. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okamoto Y., Nguyen A.T., Yoshioka M., Iehisa J.C.M., Takumi S. Identification of Quantitative Trait Loci Controlling Grain Size and Shape in the D Genome of Synthetic Hexaploid Wheat Lines. Breed. Sci. 2013;63:423–429. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.63.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill B.S., Friebe B., Raupp W.J., Wilson D.L., Cox T.S., Sears R.G., Brown-Guedira G.L., Fritz A.K. Wheat genetics resource center: The first 25 years. Adv. Agron. 2006;1:73–136. doi: 10.1016/S0065-211389002-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bacon R.K., Kelly J.T., Milus E.A., Parsons C.E. Registration of Soft Wheat Germplasm AR93005 Resistant to Leaf Rust. Crop Sci. 2006;46:1398. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2005.0273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh R.P., Huerta-Espino J., Sharma R., Joshi A.K., Trethowan R. High Yielding Spring Bread Wheat Germplasm for Global Irrigated and Rainfed Production Systems. Euphytica. 2007;157:351–363. doi: 10.1007/s10681-006-9346-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin J.N., Carver B.F., Hunger R.M., Cox T.S. Contributions of Leaf Rust Resistance and Awns to Agronomic and Grain Quality Performance in Winter Wheat. Crop Sci. 2003;43:1712. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2003.1712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox T.S., Raupp W.J., Gill B.S. Leaf Rust-Resistance Genes Lr41, Lr42, and Lr43 Transferred from Triticum Tauschii to Common Wheat. Crop Sci. 1994;34:339. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1994.0011183X003400020005x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Czembor P.C., Radecka-Janusik M., Pietrusińska A., Czembor H.J. In: Proceedings of the 11th International Wheat Genetics Symposium, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 24–29 August 2008. Appel R., Eastwood R., Lagudah E., Langridge P., Mackay M., McIntyre L., Sharp P., editors. Sydney University Press; Sidney, Australia: 2008. pp. 739–740. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun X., Bai G., Carver B.F., Bowden R. Molecular mapping of wheat leaf rust resistance gene Lr42. Crop Sci. 2010;50:59–66. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2009.01.0049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Z., Bowden R.L., Bai G. Molecular markers for leaf rust resistance gene Lr42 in Wheat. Crop Sci. 2013;53:1566–1570. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2012.09.0532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Barley Genome Sequencing Consortium. Mayer K.F., Waugh R., Brown J.W., Schulman A., Langridge P., Platzer M., Fincher G.B., Muehlbauer G.J., Sato K., et al. A physical, genetic and functional sequence assembly of the barley genome. Nature. 2012;491:711–716. doi: 10.1038/nature11543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo M.-C., Gu Y.Q., You F.M., Deal K.R., Ma Y., Hu Y., Huo N., Wang Y., Wang J., Chen S., et al. A 4-gigabase physical map unlocks the structure and evolution of the complex genome of Aegilops tauschii, the wheat D-genome progenitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:7940–7945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219082110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium (IWGSC) IWGSC RefSeq principal investigators. Appels R., Eversole K., Feuillet C., Keller B., Rogers J., Stein N., IWGSC whole-genome assembly principal investigators. Pozniak C.J., et al. Shifting the Limits in Wheat Research and Breeding Using a Fully Annotated Reference Genome. Science. 2018;361:eaar7191. doi: 10.1126/science.aar7191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El-Gebali S., Mistry J., Bateman A., Eddy S.R., Luciani A., Potter S.C., Qureshi M., Richardson L.J., Salazar G.A., Smart A., et al. The Pfam Protein Families Database in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D427–D432. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolmer J., Phytopathology P.D. Gene Expression in the Triticum Aestivum-Puccinia Recondita f. Sp. tritici gene-for-gene system. Phytopathology. 1994;84:437–440. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-84-437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feuillet C., Travella S., Stein N., Albar L., Nublat A., Keller B. Map-Based Isolation of the Leaf Rust Disease Resistance Gene Lr10 from the Hexaploid Wheat (Triticum aestivum, L.) Genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:15253–15258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2435133100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang L., Brooks S.A., Li W., Fellers J.P., Trick H.N., Gill B.S. Map-Based cloning of leaf rust resistance gene lr21 from the large and polyploid genome of bread wheat. Genetics. 2003;164:655–664. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.2.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cloutier S., McCallum B.D., Loutre C., Banks T.W., Wicker T., Feuillet C., Keller B., Jordan M.C. Leaf rust resistance gene Lr1, isolated from bread wheat (Triticum aestivum, L.) is a member of the large psr567 gene family. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007;65:93–106. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thind A.K., Wicker T., Šimková H., Fossati D., Moullet O., Brabant C., Vrána J., Doležel J., Krattinger S.G. Rapid Cloning of Genes in Hexaploid Wheat Using Cultivar-Specific Long-Range Chromosome Assembly. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017;35:793–796. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Periyannan S., Moore J., Ayliffe M., Bansal U., Wang X., Huang L., Deal K., Luo M., Kong X., Bariana H., et al. the gene Sr33, an ortholog of barley mla genes, encodes resistance to wheat stem rust race Ug99. Science. 2013;341:786–788. doi: 10.1126/science.1239028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saintenac C., Zhang W., Salcedo A., Rouse M.N., Trick H.N., Akhunov E., Dubcovsky J. Identification of wheat gene Sr35 that confers resistance to Ug99 stem rust race group. Science. 2013;341:783–786. doi: 10.1126/science.1239022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steuernagel B., Periyannan S.K., Hernández-Pinzón I., Witek K., Rouse M.N., Yu G., Hatta A., Ayliffe M., Bariana H., Jones J.D.G., et al. Rapid cloning of disease-resistance genes in plants using mutagenesis and sequence capture. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:652–655. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu W., Frick M., Huel R., Nykiforuk C.L., Wang X., Gaudet D.A., Eudes F., Conner R.L., Kuzyk A., Chen Q., et al. The stripe rust resistance gene Yr10 encodes an evolutionary-conserved and unique CC–NBS–LRR sequence in wheat. Mol. Plant. 2014;7:1740–1755. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssu112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi G., Zhang Z., Friesen T.L., Raats D., Fahima T., Brueggeman R.S., Lu S., Trick H.N., Liu Z., Chao W., et al. The hijacking of a receptor kinase–driven pathway by a wheat fungal pathogen leads to disease. Sci. Adv. 2016;2:e1600822. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saintenac C., Lee W.-S., Cambon F., Rudd J.J., King R.C., Marande W., Powers S.J., Bergès H., Phillips A.L., Uauy C., et al. Wheat receptor-kinase-like protein stb6 controls gene-for-gene resistance to fungal pathogen zymoseptoria tritici. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:368–374. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sánchez-Martín J., Steuernagel B., Ghosh S., Herren G., Hurni S., Adamski N., Vrána J., Kubaláková M., Krattinger S.G., Wicker T., et al. Rapid gene isolation in barley and wheat by mutant chromosome sequencing. Genome Biol. 2016;17:221. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1082-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang X.-Q., Röder M.S. High-density genetic and physical bin mapping of wheat chromosome 1D reveals that the powdery mildew resistance gene Pm24 is located in a highly recombinogenic region. Genetica. 2011;139:1179–1187. doi: 10.1007/s10709-011-9620-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gill K.S., Gill B.S., Endo T.R., Taylor T. Identification and high-density mapping of gene-rich regions in chromosome group 1 of wheat. Genetics. 1996;144:1001–1012. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.2.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stakman E.C., Stewart D.M., Loegering W.Q. Identification of physiologic races of Puccinia graminis var. tritici. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 1981;3:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roelfs A.P., Bushnell W.R., San O., New D., London Y., Montreal T., Tokyo S. The Cereal Rusts: Diseases, Distribution, Epidemiology, and Control. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saghai-Maroof M.A., Soliman K.M., Jorgensen R.A., Allard R.W. Ribosomal DNA Spacer-Length Polymorphisms in Barley: Mendelian Inheritance, Chromosomal Location, and Population Dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:8014–8018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.24.8014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.The R Development Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2017. [(accessed on 18 March 2019)]. Available online: https://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Givry S., Bouchez M., Chabrier P., Milan D., Schiex T. CARHTA GENE: Multipopulation integrated genetic and radiation hybrid mapping. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:1703–1704. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kosambi D.D. The estimation of map distances from recombination values. Ann. Eugen. 1943;12:172–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1943.tb02321.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Voorrips R.E. MapChart: Software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J. Hered. 2002;93:77–78. doi: 10.1093/jhered/93.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luo M.-C., Gu Y.Q., Puiu D., Wang H., Twardziok S.O., Deal K.R., Huo N., Zhu T., Wang L., Wang Y., et al. Genome sequence of the progenitor of the wheat d genome aegilops tauschii. Nature. 2017;551:498. doi: 10.1038/nature24486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Altschul S.F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.