Abstract

Background

Non-Technical Skills (NTS) are becoming more important in medical education. A lack of NTS was identified as a major reason for unsafe patient care, favouring adverse events and team breakdown. Therefore, the training of NTS should already be implemented in undergraduate teaching. The goal of our study was to develop and validate the Anaesthesiology Students’ Non-Technical Skills (AS-NTS) as a feasible rating tool to assess students’ NTS in emergency and anaesthesiology education.

Methods

The development of AS-NTS was empirically grounded in expert- and focus groups, field observations and data from NTS in medical fields. Validation, reliability and usability testing was conducted in 98 simulation scenarios, during emergency and anaesthesiology training sessions.

Results

AS-NTS showed an excellent interrater reliability (mean 0.89), achieved excellent content validity indexes (at least 0.8) and was rated as feasible and applicable by educators. Additionally, we could rule out the influence of the raters’ anaesthesiology and emergency training and experience in education on the application of the rating tool.

Conclusions

AS-NTS provides a structured approach to the assessment of NTS in undergraduates, providing accurate feedback. The findings of usability, validity and reliability indicate that AS-NTS can be used by anaesthesiologists in different year of postgraduate training, even with little experience in medical education.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12909-019-1609-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Non-technical skills, Simulation, Education

Background

In patient care, both Technical Skills (TS) and Non-Technical Skills (NTS) are necessary to maintain best practice as well as reach a high level of expertise [1]. TS are routinely taught in trainee programs. However, evaluation and assessment of NTS have been missing for a long time [2, 3]. NTS are defined as “the cognitive, social and personal resource skills that complement technical skills and contribute to safe and efficient task performance” [4].

Adverse events in high-risk settings often take place due to deficiencies in NTS [5], which has been shown in various fields such as aviation and nuclear energy [6–8] and has also been confirmed for medical care: up to 70% of adverse events are due to human errors [9–11]. In order to reduce medical errors, good NTS and improved teamwork are essential [12].

NTS interventions and mostly feedback on NTS have shown to have positive effects on team performance, concluding that good patient care requires TS and NTS, which have been found to correlate in crew resource management [13, 14] and to foster improved clinical performance like quicker problem solving in simulated operating theatre environment [15]. The positive effects of NTS also encompass enhanced patient safety. Salas et al. showed in a meta-analysis the positive effects of NTS on team members’ reactions and attitudes related to teamwork safety [16]. Other studies pointed out positive effects of NTS on clinical performance (TS) and on patient outcome like surgical complications and morbidity [17].

Knowledge of necessity and benefits of NTS lead many institutions to emphasize the importance of interpersonal skills [13, 16–21] and these departments implemented crew-resource training programs in their curricula, primarily focussing on NTS during postgraduate training [22].

The training of NTS should not only be focused in postgraduate training - undergraduate curricula and education should already integrate the concept of “patient safety”, directly addressing, teaching and assessing NTS [23, 24]. Only a few studies have investigated the effect of teaching NTS in undergraduates. Hagemann et al. showed that even one brief seminar had positive effects on undergraduates’ NTS [21].

The German Association for Medical Education has acknowledged the repeatedly expressed need of NTS implementation in undergraduate education by publishing a “Learning Objective Catalogue for Patient Safety in Undergraduate Medical Education”, which has the aim to unify the curricular targets in German medical faculties [25]. However, a concrete curriculum, implementation or teaching strategy for NTS in undergraduate education is not given yet. In addition, due to a missing conventional rating tool a structured assessment of NTS in undergraduates is often lacking.

To create and realize an implementation and teaching strategy for NTS in undergraduates, at first the structured assessment of NTS with a robust method is necessary [4], in order to provide specific and formative feedback and to monitor the learning progress in undergraduates.

Several rating tools for assessing NTS in medical professionals are available. They are helpful to provide feedback which is not based on “gut feeling” and to speak “the same language” during the feedback process [26–31]. However, the existing rating tools, such as the Anaesthetists’ Non-Technical Skills (ANTS) [32], are very complex and not designed for undergraduates or junior residents, as ANTS is developed for experienced anaesthesiologists to rate trainees who have reached certain TS, which limits its broad application in undergraduate education. A feasible application is further limited as for raters a two-day training with the rating scheme is required. The use of ANTS delays the feedback loop, as the NTS ratings are based on video clips of the training sessions, which are evaluated after the training [5].

The goal of this study was to develop a rating tool to assess NTS in undergraduate education in emergency medicine and anaesthesiology: Anaesthesiology Students’Non-Technical Skills (AS-NTS). The tool is supposed to be feasible and easily handled without the necessity for video recording or extended instructions and trainings for the user.

Methods

Study design

This study was performed at the Department of Anaesthesiology in the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany. The study was conducted in the period of Janurary 2017 to December 2017. Undergraduates and residents in anaesthesiology participated in this study with a stepwise design in order to develop and validate a rating tool for NTS in undergraduates in anaesthesiology. The development took place in four steps (Table 1), empirically grounded on qualitative and quantitative research methods:

Review of published literature (expert group)

Focus group and half-structured interviews

Field observation

Implementation and validation

Table 1.

Development steps of AS-NTS

| Qualitative and quantitative research methodology | Conducted Steps | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Development | |||

| Development step | 1. | Expert groupa |

• Literature search • Development of a NTS list and discussion of their relevance for undergraduates |

| 2. | Focus groupsb and half-structured interviews |

• Discussion of NTS • Development of a hierarchical structure of NTS |

|

| Validation | |||

| Development step | 3. | Field Observation |

• Testing of feasibility and practicality • Evaluation if the skills were observable |

| 4. |

a) Evaluation questionnaire b) Analyzing the interrater reliability |

• Calculation of the content validity indexc • Validation of usability and feasibility • Assessment of NTS in 98 simulation scenarios during emergency training sessions by two/ three independent raters |

|

Legend: a The expert group consisted of two anaesthesiology specialists with profound experience in medical education and of two specialists who work on the assessment of psycho-social skills in Multiple Mini Interviews for the purpose of student selection, one of them being a psychologist and one of them highly qualified in medical education. The composition of the expert group was chosen to combine expertise of anaesthesiology, medical education and psychology

bThe focus group consisted of five anaesthesiology specialists, two male and three female participants, with a median age of 34.8 years. The mother language of all participants is German and they all had completed their residency at the Department of Anaesthesiology, University Medical Center Hamburg Eppendorf. The qualification criteria to join the focus group were 1) to be at anaesthesiology specialist level and 2) to work regularly in anaesthesiology and emergency medicine and in medical teaching. Routine in emergency care was required in order to link the theoretical discussion about the NTS with reality settings

cThe content validity index for each dimension was calculated, reflecting the proportion of relevance [33]

Table 1 shows a scheme of the conducted developmental steps and underlying research methods.

A detailed explanation of the development is given in the Additional file 1.

Study setting: assessment of NTS during emergency and anaesthesiology training sessions

The undergraduate curriculum of the Medical Faculty of Hamburg has implemented emergency training sessions in nearly every semester, in order to experience the students in emergency medicine. We use high fidelity simulators (Rescue Anne Laerdal) which are suitable for training technical skills such as endotracheal intubation, defibrillation or drug administration.

NTS were assessed in four different training sessions (Advanced cardiac life support I, II, III and operation room simulation) of four different semesters. In each training session a pre-existing set of standardized simulation scenarios were used (13 in total, a detailed description of the simulation scenarios is provided in the Additional file 1).

The simulation scenarios are standardised and solely for each type of training session. For example, the training session “Advanced cardiac life support II (ACLS II)”, which is held in the 3rd year of undergraduate education, includes the scenarios: “Hyperkalaemia”, “Hypothermia” and “Aspiration”.

In each training session every student is assigned to a small group which rotates through each simulation scenario.

With each following semester, the simulation scenarios require more advanced TS and NTS. In order to rule out that low NTS skills are due to technical skills being not proceduralized we decided to test our rating system in students who had already passed the basic life support training in following training sessions:

○ Advanced cardiac life support I (ACLS I: 2nd or 3rd year undergraduates, pre-existing simulation scenarios: 2; number of rated simulation scenarios for interrater agreement analysis: 20)

○ Advanced cardiac life support II (ACLS II: 3rd year undergraduates, pre-existing simulation scenarios: 3; number of rated simulation scenarios for interrater agreement analysis: 24)

○ Advanced cardiac life support III (ACLS III: 4th year undergraduates, pre-existing simulation scenarios: 5; number of rated simulation scenarios for interrater agreement analysis: 23)

○ Operation room (OR) simulation (3rd or 4th year undergraduates, pre-existing simulation scenarios: 3; number of rated simulation scenarios for interrater agreement analysis: 31)

In each training session, the undergraduates are divided into groups of three. Each of these groups rotates through the simulation scenarios of the training session. In each simulation scenario one student takes the role of the physician, the other two that of paramedics or anaesthetic co-workers. The student in the role of the physician leads the team and delegates basic tasks such as establishing the monitoring, preparing defibrillation and other required medical procedures to the other team members. Therefore, only this student was evaluated by the two or three supervising anaesthesiologists, using the AS-NTS.

Raters and interrater reliability

Twenty-one anaesthesiologists (Table 2) conducted the training sessions during the study period. In 67 emergency simulation scenarios two of them rated the students independently, in the 31 operating room simulation scenarios three raters were involved. The raters who rated the same simulation scenario, did not discuss their results while rating, in order to rule out cognitive bias.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the twenty-one raters

| Sex | Mean Age | Experience in medical Education | Anaesthesiology training |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female: 13 | 31.7 years | High*1: 5 | Attendings: 5 |

| Male:8 | Medium*2: 8 | 5th year residents: 5 | |

| Low*3:8 | 4th year residents: 4 | ||

| 3rd year residents: 4 | |||

| 2nd year residents: 3 |

Legend: *1: High experience: organization of and high involvement in undergraduate teaching *2: Medium experience: certain routine in undergraduate teaching *3: Low experience: introduced to undergraduate teaching during the study time

The rater teams changed frequently based on the teaching schedule. The raters all received a five-minute introduction into the AS-NTS.

The interrater-reliability was investigated using a two-step approach.

In the first step a classical analysis of interrater-reliability was conducted, analysing data from rating pairs. To rule out agreement by chance, the intraclass correlation (ICC) from six pairs of raters were calculated, which had rated at least six simulation scenarios together. The first analysis included 67 of the total of 98 simulation scenarios. In five of the six pairs the first author (R1) took part (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of the six pairs of raters

| Pairings | Sex | Age | Experience in medical education | Anaesthesiology training | Number of rated simulation scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1/R2 | F/M | 32/27 | High/Low | A./2nd year resident | 17 |

| R1/R3 | F/M | 32/27 | High/Middle | A./3rd year resident | 14 |

| R1/R4 | F/F | 32/34 | High/High | A./5th year resident | 7 |

| R1/R5 | F/M | 32/38 | High/Middle | A./A. | 8 |

| R1/R6 | F/F | 32/29 | High/Low | A./4th year resident | 14 |

| R7/R8 | M/F | 31/28 | Middle/Low | 5th−/3rd year resident | 7 |

Abbreviation: A Attending, R Rater

In the second step of the interrater-reliability analysis, the whole data set from the 98 simulation scenarios was analysed. To rule out that either the strong involvement of R1 in the development process of AS-NTS or the medical training had an effect on the interrater reliability, data was aggregated across raters being in the same year of training. This allowed us to investigate the relationship between medical expertise and rating agreement (Table 4).

Table 4.

Ratings and comparisons by anaesthesiology training after data aggregation

| Year of anaesthesiology training | Number of rated simulation scenarios |

|---|---|

| Attending (n = 5) vs 2nd year resident (n = 3) | 23 |

| Attending (n = 5) vs 3rd year resident (n = 4) | 16 |

| Attending (n = 5) vs 4th year resident (n = 4) | 20 |

| Attending (n = 5) vs 5th year resident (n = 5) | 11 |

| 4th year (n = 4) vs 3rd year resident (n = 4) | 15 |

| 5th year (n = 5) vs 3rd year resident(n = 4) | 13 |

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 23.0. Intraclass correlation (ICC) was used for ordinally scaled data and Cohens Kappa for nominally scaled data to calculate interrater reliability. We used the one-way random effects model to calculate the ICCs [34]. Values of ICC and kappa below 0.40 are interpreted as poor correlation, between 0.40 and 0.59 as fair correlation, between 0.60 and 0.74 as good correlation and between 0.75 and 1.00 as excellent correlation [35].

Results

Development of the AS-NTS assessment tool

The literature search resulted in 12 different NTS important in anaesthesiology (Table 5). The discussions in the focus- and expert group revealed, that not all of these NTS are highly important for undergraduates. During the field observations some NTS were difficult to observe. Using the results of the focus group discussions we defined new dimensions specifically for undergraduates, symbiosing some pre-defined NTS:

Planing tasks, prioritising and conducting

Teamwork: exchanging information and leading the team

Team orientation

Table 5.

Hierarchical mapping of Non-Technical skills and multi-step development of AS-NTS

| Non-Technical Skill | Step 1: Literature | Step 2: Focus group | Step 3: Field Observation | Part of rating tools | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highly important | Important | Skill (precursor skill) Observable | Skill difficult to observe | ANTS system | AS-NTS | |||

| Situational awareness | [26, 28, 30, 36–45] | * | * | * | ||||

| Prioritising (Planning Tasks) | [12, 31, 46] | * | * | * | * |

DIMENSION 1: Planning tasks, prioritising and problem solving |

||

| Decision-making | [12, 28, 41, 42, 47–54] | * | (*) | * | * | |||

| Maintaining standards | [31, 38, 39, 43, 54] | * | (*) | * | * | |||

| Coordinating team members and activities | [39, 55] | * | * | * | * |

DIMENSION 2: Teamwork and leadership |

||

| Communication | [12, 22, 26, 28–31, 38, 40, 41, 43–47, 49–51, 53–59] | * | * | * | ||||

| Leadership | [7, 12, 16, 26, 29–31, 36, 39, 41–44, 46, 47, 55–58] | * | * | * | ||||

| Using authority and assertiveness | [38, 39, 56] | * | (*) | * | * | |||

| Team-building | [12, 28, 31, 36, 38, 39, 56] | * | * | * |

DIMENSION 3: Team orientation |

|||

| Team orientation/ Teamwork | [12, 28, 29, 31, 36, 38, 39, 45, 46, 56–58] | * | * | * | * | |||

| Resolving conflicts/ problems | [12, 39, 42, 47, 56] | * | * | |||||

| Supporting others | [22, 28, 39, 42] | * | * | * | ||||

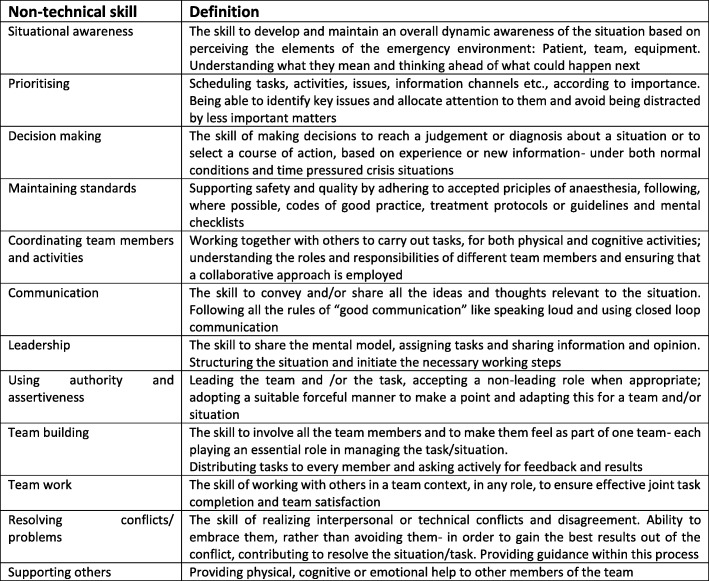

Table 5 displays the created list of the NTS and the further conducted steps which were decisive for the inclusion of each skill. The last column illustrates which NTS is part of ANTS and AS-NTS. Figure 1 displays the definition of the NTS.

Fig. 1.

Definition of the NTS. The definitions were extracted from the cited taxonomies in Table 5, mostly the ANTS system

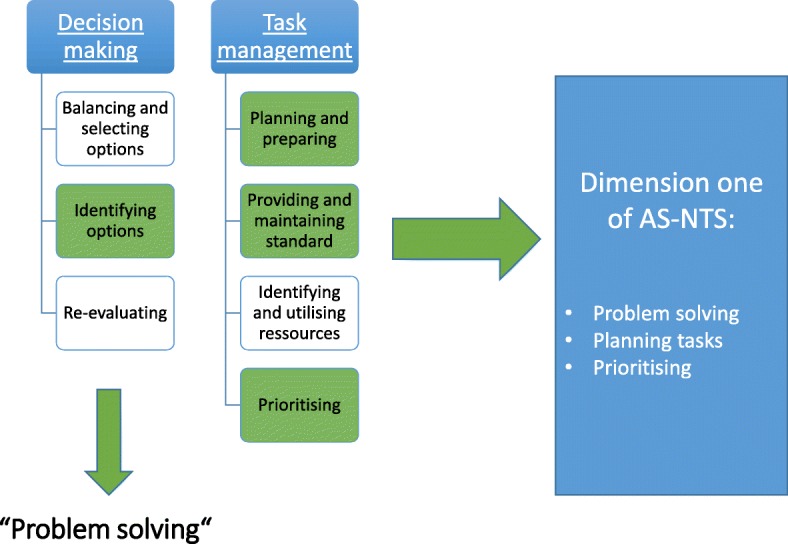

The first dimension of AS-NTS:

“Planning tasks, prioritizing and problem solving” resulted as a compound, mainly formed by pre-defined NTS dimensions “Decision making” and “Task management” (Fig. 2). The elements that were considered important in undergraduates and therefore created the basis to define the first dimension of AS-NTS are highlighted.

Fig. 2.

Underlying NTS for dimension one of AS-NTS

“Coordinating team members”, “communication” and “Leadership” were regarded as highly important in the focus group and performance could be observed in different levels during the field observation, therefore these elements created the basis for dimension two of ANAESTHESIOLOGY STUDENTS’ NON-TECHNICAL SKILLS: “Teamwork and leadership”.

Leadership, defined as the skill of directing others, coordinating, managing workload and motivating others [37] is often separated into two independent dimensions allowing for the assessment of different leadership styles [60] distinguishing between task orientation and team orientation. In this leadership model, “Task orientation” is closely related to our first two AS-NTS dimensions, therefore we decided to add “Team orientation” as third and final dimension of the AS-NTS. “Teamwork and leadership” emphasizes the collaborative processes to perform a task, whereas “Team orientation” focuses on the collaborative processes to build a team.

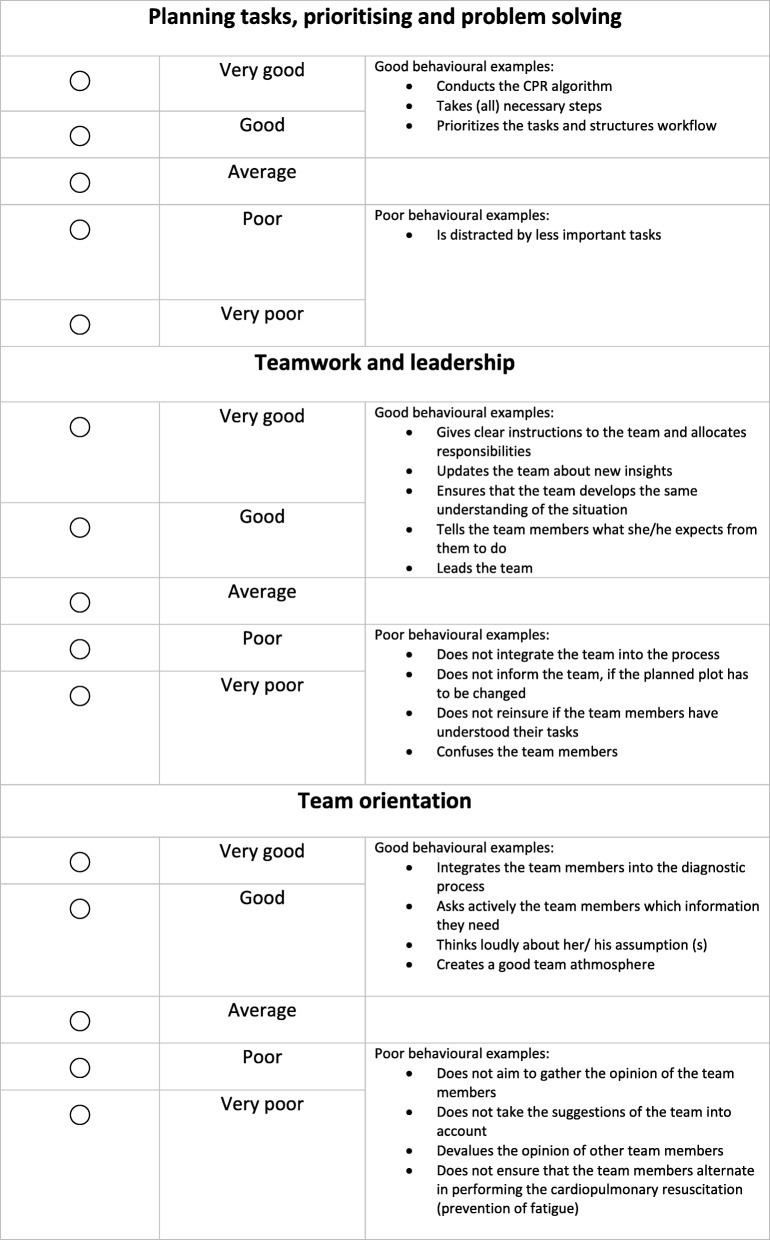

In contrast to the ANTS, performance is rated in the AS-NTS on the three dimensions and not on the level of skills. However, the underlying skill structure was used to give behaviorally anchored rating examples to clarify what a “good” or “poor” performance on each dimension might look like. In the final AS-NTS assessment tool (Fig. 3), a five-point Likert scale was used for each dimension, although the ANTS system has a four-point scale [32]. Cook et al. could show that, in regard to reliability and interrater reliability, there are no differences in 5- and 9- point scales in mini-clinical evaluation exercise [61].

Fig. 3.

AS-NTS assessment tool (english version; the original German version has been added to the Additional file 1)

Feasibility and content validity of the scoring system

The interviews with eight anaesthesiologists in their first year of residency, who used both the AS-NTS and ANTS in simulation training (including video tapings), showed that no further dimension had to be added to the AS-NTS rating tool (step 4). Furthermore, they confirmed the feasibility of AS-NTS and concluded that in undergraduates, as well as in the first 2 years of residency in anaesthesiology, the ANTS system is too complex.

Without video tapings it is nearly impossible to complete ANTS, due to time shortness. This was already pointed out by the developers [5, 32]. The eight anaesthesiologists discovered the rating of the videos to be very time consuming and delaying the feedback loop.

These anaesthesiology trainees decided to continue their postgraduate training curriculum using AS-NTS, rather than ANTS, for their first 2 years of residency.

The results from an additional evaluation questionnaire, completed by 21 anaesthetits, who had used the rating tool at least three times in undergraduate medical education, confirmed that the AS-NTS was feasible and practical (Additional file 1: Table S1). Additionally, they rated the importance of each dimension of AS-NTS.

The content validity index for each dimension was calculated, reflecting the proportion of relevance [62]. The calculated content validity index for the first dimension of AS-NTS was 0.9, for the second dimension 0.95 and for the third dimension 0.8. A content validity index of 0.75 or higher is considered as “excellent” [33].

Interrater reliability

The interrater reliability reached high levels of agreement (Table 6), except for dimension two, in the group of 3rd vs. 5th year residents (fair correlation). The ICC indicated a high rater agreement regardless of educational experience, training in anaesthesiology or familiarity with the AS-NTS rating tool.

Table 6.

Interrater reliability of the six pairs of raters and of all data (98 rated simulation scenarios)

| Raters | ICC D.1 |

ICC D.2 |

ICC D.3 |

ICC Overall | Cohen’s Kappa D.1 |

Cohen’s Kappa D.2 |

Cohen’s Kappa D.3 |

Cohen’s Kappa Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interrater reliability of six pair of raters (67 emergency and anaesthesiology simulation scenarios) | ||||||||

| R1/R2 | 0.925 | 0.955 | 0.882 | 0.922 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.92 |

| R1/R3 | 0.897 | 0.856 | 0.945 | 0.886 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.78 | 0.88 |

| R1/R4 | 0.855 | 0.825 | 0.874 | 0.837 | 0.833 | 0.853 | 0.854 | 0.837 |

| R1/R5 | 0.943 | 0.949 | 1 | 0.976 | 1 | 0.87 | 0.78 | 0.88 |

| R1/R6 | 0.905 | 0.978 | 0.943 | 0.945 | 0.893 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| R7/R8 | 0.706 | 0.706 | 0.706 | 0.681 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.56 |

| Interrater reliability of the 67 emergency simulation scenarios after data aggregation across raters’anaesthesiology training | ||||||||

| A./2nd year | 0.880 | 0.893 | 0.830 | 0.868 | 0.87 | 0.8 | 0.82 | 0.87 |

| A./3rd year | 0.915 | 0.900 | 0.950 | 0.917 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.95 | 0.92 |

| A./4th year | 0.871 | 0.937 | 0.884 | 0,897 | 0.91 | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.86 |

| A./5th year | 0.811 | 0.787 | 0.834 | 0.805 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.87 | 0.78 |

| 4th/3rd year | 0.729 | 0.767 | 0.722 | 0.733 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.74 |

| 5th/3rd year | 0.650 | 0.500 | 0.680 | 0.624 | 0.73 | 0.48 | 0.68 | 0.63 |

| Interrater reliability of the 31 OR simulation scenarios with 3 raters per each simulation scenario | ||||||||

| ICC Dimension one | ICC Dimension two | ICC Dimension three | ICC overall | |||||

| 0.737 | 0.780 | 0.684 | 0.738 | |||||

Abbreviations: A. Attending, R.: Rater, Year Year of anaesthesiology training

Discussion

The development of the AS-NTS was performed in a stepwise approach, beginning with a review of pre-existing literature, continuing with focus group analysis and field observation, and ending with implementation and validation.

The steps were processed by means of empirical and qualitative research methods, which have gained a broad application in medical research [63–71].

During the field observations some skills proved to be difficult to observe and excluded from ANAESTHESIOLOGY STUDENTS’ NON-TECHNICAL SKILLS, based on developmental guidelines of assessment tools described by Abell et al., who recommend items to be excluded, if they are not observable in at least 50% of field observations [72].

Nonetheless, the excluded skills are part of most existing NTS taxonomies and regarding the importance of these skills, one might argue that they should still be taught and addressed in undergraduate education.

However, acquiring and refining NTS is an individual and ongoing process [73]. Therefore, in undergraduate training pre-cursors of some NTS should be assessed and evaluated. Further, most of the taxonomies from which the NTS list was extracted, are developed for postgraduate training- focussing on specialist level, which makes these skills not one to one transferable to undergraduates.

Those skills should be focused in more advanced educational levels, mostly in postgraduate training. Nevertheless, the aim of the study was to include as many NTS as possible into the ANAESTHESIOLOGY STUDENTS’ NON-TECHNICAL SKILLS, in order to assess them in undergraduates to provide accurate feedback, enhancing the learning process. [74] For this goal, skills were redefined during the development of ANAESTHESIOLOGY STUDENTS’ NON-TECHNICAL SKILLS, symbiosing some pre-defined NTS and focusing more on pre-cursors and underlying elements of skills. This adaptation process was not solely based on the expert- and focus groups- but was supported by literature and resulted in the new dimensions of ANAESTHESIOLOGY STUDENTS’ NON-TECHNICAL SKILLS, specifically designed for undergraduates. The adaptation step was necessary, as some NTS are highly important but not fully developed in undergraduates.

Transferred to the first dimension of ANAESTHESIOLOGY STUDENTS’ NON-TECHNICAL SKILLS, two main dimensions of described NTS (“Decision making” and “Task management”) were symbiosed to the first AS-NTS dimension “Planning tasks, prioritizing and problem solving”.

This might lead to the assumption a specific assessment of these skills is not possible, as they are assessed in the same dimension of performance and in pre-existing rating tools, they are separately assessed.

This objection can be warded by focusing on the developmental rational and existing literature:

“Decision making” is a complex skill which is divided into subskills and rated separately by some behavioral taxonomies [28, 29, 32]. Flowerdew et al. pointed out that it is not only making the decision which is of great importance, but also following the effects caused by the decision, like planning and prioritizing tasks to conduct the decision [38]. Here, “Decision making” is directly linked to the dimension “Task management”, which includes the elements: “Planning and preparing, prioritizing, providing and maintaining standard, identifying and utilizing resources”. Conducting the elements of “Task management” is the following consequence after “a decision is made”.

The comprehensiveness of “Decision making” and “Task management” regarding the training level of undergraduates was pointed out repeatedly, leading to the exclusion of these dimensions and focusing on some elements of these skills.

The elements of “Decision making” are: Identifying options, balancing risks, selecting options and re-evaluating [7, 20, 32, 56, 75].

Identifying options is necessary to solve a problem- in the decision making loop the risks and benefits of the solving strategy are re-evaluated – this concept of decision making is applicable in more complex scenarios than in undergraduate simulation training. Therefore, the focus group discussed and agreed to include “problem solving” as a less complex proxy of decision making into the first dimension of AS-NTS.

The strength of this study was scrutinizing the interrater reliability from different viewpoints. The interrater reliability was not only defined by a few designated raters, as in classical approaches. A two-step approach was chosen to analyse rater agreement, simultaneously examining if personal background (a.e. year of anaesthesiology training or experience in medical education) might influence ratings. First, agreement of rater pairs were analysed with a sufficient number of ratings, excluding agreement by chance, then data aggregation of the full sample was conducted based on anaesthesiology training, to calculate the interrater reliability. AS-NTS achieved excellent Interrater reliability, only within the group of 5th year vs. 3rd year anaesthesiology residents, the ICC and Cohens Kappa were “good” and only “fair” for dimension two of AS-NTS.

Data aggregation in the full sample, supports the result that the rating agreement is detached from anaesthesiology training and experience in medical education, fostering the usability of AS-NTS.

The strong involvement of Rater 1 in the assessment of the interrater reliability might lead to the assumption one rater could influence all the other raters. Regarding our results, this is not the case, as data aggregation across all raters, in which Rater 1 is not represented predominantly, showed high agreement on ratings as well.

The dimensions of the final version of AS-NTS achieved excellent content validity indexes according to a guideline for evaluating standardized assessment instruments [35]. However, one weakness of the study is that the calculation of the content validity index was only calculated from the evaluation of twenty-one anaesthesiologists. Although there is no predefined sample size required to establish content validity [76], the effect of agreement by chance is higher in a small sample.

The AS-NTS has high potential to improve NTS assessment in undergraduate education and ultimately patient safety, because a lack of NTS leads to adverse events in high-risk settings [5]. A recent study by Hagemann et al. showed that NTS in undergraduate students are improved after only one seminar [21]. Due to its good feasibility, the AS-NTS could be applied to all students as a standardised assessment and feedback tool.

Limitations

The AS-NTS has only been tested in German language at one institution with a limited number of teachers. Further studies should be conducted to establish the validity, reliability and feasibility of the English version.

Conclusion

AS-NTS provides a structured approach to the assessment of NTS in undergraduates, providing accurate feedback. The findings of usability, validity and reliability indicate that the AS-NTS can be used by anaesthesiologists in different year of postgraduate training, even with little experience in medical education.

Additional file

AS-NTS. (DOCX 93 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all medical teachers from the Department of Anaesthesiology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf.

Abbreviations

- ANTS

Anaesthesiology Non-Technical Skills

- AS-NTS

Anaesthesiology Students’Non-Technical Skills

- CVI

Content Validity Index

- ICC

Intraclass correlation

- NTS

Non-Technical skills

- TS

Technical skills

Authors’ contributions

PM-K made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. She has been involved in drafting the manuscript and given final approval of the version to be published. She agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. AK made substantial contributions to acquisition of data. She has been involved in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and has given final approval of the version to be published. She agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. WH made substantial contributions to conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data. He has been involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. He has given final approval of the version to be published. He agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. LS-U made substantial contributions to acquisition of data. She has been involved in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and has given final approval of the version to be published. She agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. SZ made substantial contributions to conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data. He has been involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. He has given final approval of the version to be published. He agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. JCK made substantial contributions to conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data. He has been involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. He has given final approval of the version to be published. He agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was not supported by any funding.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The assessment of NTS in simulation scenarios in undergraduate education was performed after approval by the local ethics committee in January 2017 (Ethikkommission der Ärztekammer Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany; Correspondence PV5563). Written informed consents were obtained from the study participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Stefan Zimmermann and Jens Christian Kubitz contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Parisa Moll-Khosrawi, Phone: +4940741018364, Email: pmollkho@icloud.com.

Anne Kamphausen, Email: a.kamphausen@uke.de.

Wolfgang Hampe, Email: hampe@uke.de.

Leonie Schulte-Uentrop, Email: lschulte@uke.de.

Stefan Zimmermann, Email: auswahlverfahren@uke.de.

Jens Christian Kubitz, Email: j.kubitz@uke.de.

References

- 1.Weinger MB. Experience≠ ExpertiseCan simulation be used to tell the difference? The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. 2007;107(5):691–694. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000287288.83609.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaba DM, DeAnda A. The response of anesthesia trainees to simulated critical incidents. Anesth Analg. 1989;68(4):444–451. doi: 10.1213/00000539-198904000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fletcher G, McGeorge P, Flin RH, Glavin RJ, Maran NJ. The role of non-technical skills in anaesthesia: a review of current literature. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88(3):418–429. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flin RH, O'Connor P, Crichton M. Safety at the sharp end: a guide to non-technical skills: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.; 2008.

- 5.Flin R, Patey R, Glavin R, Maran N. Anaesthetists’ non-technical skills. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105(1):38–44. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salas Eduardo, Burke C. Shawn, Bowers Clint A., Wilson Katherine A. Team Training in the Skies: Does Crew Resource Management (CRM) Training Work? Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society. 2001;43(4):641–674. doi: 10.1518/001872001775870386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flin R, Martin L, Goeters K-M, Hormann H, Amalberti R, Valot C, et al. Development of the NOTECHS (non-technical skills) system for assessing pilots’ CRM skills. Human Factors and Aerospace Safety. 2003;3:97–120. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flin R. Safe in their hands?: licensing and competence assurance for safety-critical roles in high risk industries. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pierre MS, Hofinger G, Buerschaper C. Human Factors und Patientensicherheit in der Akutmedizin: Springer; 2014.

- 10.Hoffmann B, Siebert H, Euteneier A. Patient safety in education and training of healthcare professionals in Germany. Bundesgesundheitsbl Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz. 2015;58(1):87–94. doi: 10.1007/s00103-014-2075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Müller MP, Hänsel M, Stehr SN, Fichtner A, Weber S, Hardt F, et al. Six steps from head to hand: a simulator based transfer oriented psychological training to improve patient safety. Resuscitation. 2007;73(1):137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Risser DT, Rice MM, Salisbury ML, Simon R, Jay GD, Berns SD. The potential for improved teamwork to reduce medical errors in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34(3):373–383. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(99)70134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Connor P, Campbell J, Newon J, Melton J, Salas E, Wilson KA. Crew resource management training effectiveness: a meta-analysis and some critical needs. Int J Aviat Psychol. 2008;18(4):353–368. doi: 10.1080/10508410802347044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riem N, Boet S, Bould MD, Tavares W, Naik VN. Do technical skills correlate with non-technical skills in crisis resource management: a simulation study. Br J Anaesth. 2012;109(5):723–728. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doumouras A, Hamidi M, Lung K, Tarola C, Tsao M, Scott J, et al. Non-technical skills of surgeons and anaesthetists in simulated operating theatre crises. Br J Surg. 2017;104(8):1028–1036. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salas E, Wilson KA, Burke CS, Wightman DC, Howse WR. Crew resource management training research, practice, and lessons learned. Reviews of human factors and ergonomics. 2006;2(1):35–73. doi: 10.1177/1557234X0600200103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmutz J, Manser TD. Do team processes really have an effect on clinical performance? A systematic literature review. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110(4):529–544. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cannon-Bowers JA, Salas E. Team performance and training in complex environments: recent findings from applied research. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 1998;7(3):83–87. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.ep10773005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flin R, Patey R. Improving patient safety through training in non-technical skills. British Medical Journal Publishing Group. 2009;339:b3595. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon M, Darbyshire D, Baker P. Non-technical skills training to enhance patient safety: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2012;46(11):1042–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hagemann V, Herbstreit F, Kehren C, Chittamadathil J, Wolfertz S, Dirkmann D, et al. Does teaching non-technical skills to medical students improve those skills and simulated patient outcome? Int J Med Educ. 2017;8:101. doi: 10.5116/ijme.58c1.9f0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaba DM, Howard KJ, Gaba SKDM, Fish KJ, Howard SK. Crisis management in anesthesiology 1994.

- 23.Walton M, Woodward H, Van Staalduinen S, Lemer C, Greaves F, Noble D, et al. Republished paper: the WHO patient safety curriculum guide for medical schools. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87(1026):317–321. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2009.036970rep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.der Medizinischen Wissenschaften SA. Projekt „Zukunft Medizin Schweiz “–Phase lll–Aus-und Weiterbildung in Patientensicherheit und Fehlerkultur. Unter Mitarbeit von Barbara Gassmann, Jacques Haller, Martin Täuber, Peter M Suter Schweizerische Akademie der Medizinischen Wissenschaften. 2007.

- 25.Kiesewetter J, Gutmann J, Drossard S, Salas DG, Prodinger W, Mc Dermott F, et al. The learning objective catalogue for patient safety in undergraduate medical education–a position statement of the Committee for Patient Safety and Error Management of the German Association for Medical Education. GMS journal for medical education. 2016;33:1. doi: 10.3205/zma001009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim J, Neilipovitz D, Cardinal P, Chiu M, Clinch J. A pilot study using high-fidelity simulation to formally evaluate performance in the resuscitation of critically ill patients: the University of Ottawa critical care medicine, high-Fidelity simulation, and crisis resource management I study. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(8):2167–2174. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000229877.45125.CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andersen PO, Jensen MK, Lippert A, Østergaard D, Klausen TW. Development of a formative assessment tool for measurement of performance in multi-professional resuscitation teams. Resuscitation. 2010;81(6):703–711. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yule S, Flin R, Paterson-Brown S, Maran N, Rowley D. Development of a rating system for surgeons’ non-technical skills. Med Educ. 2006;40(11):1098–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas E, Sexton J, Helmreich R. Translating teamwork behaviours from aviation to healthcare: development of behavioural markers for neonatal resuscitation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2004;13(suppl 1):i57–i64. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.009811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Healey A, Undre S, Vincent C. Developing observational measures of performance in surgical teams. BMJ Qual Saf. 2004;13(suppl 1):i33–i40. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.009936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooper S, Cant R, Porter J, Sellick K, Somers G, Kinsman L, et al. Rating medical emergency teamwork performance: development of the TEAM emergency assessment measure (TEAM) Resuscitation. 2010;81(4):446–452. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fletcher G, Flin R, McGeorge P, Glavin R, Maran N, Patey R. Anaesthetists’ non-technical skills (ANTS): evaluation of a behavioural marker system. Br J Anaesth. 2003;90(5):580–588. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lynn MR. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs Res. 1986. [PubMed]

- 34.Koch GG. Intraclass correlation coefficient. Encyclopedia of statistical sciences. 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assess. 1994;6(4):284. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaba DM, Howard SK, Flanagan B, Smith BE, Fish KJ, Botney R. Assessment of clinical performance during simulated crises using both technical and behavioral ratings. The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. 1998;89(1):8–18. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199807000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salas E, Burke CS, Stagl KC. Developing teams and team leaders: strategies and principles. Leader development for transforming organizations: growing leaders for tomorrow. 2004. pp. 325–355. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flowerdew L, Brown R, Vincent C, Woloshynowych M. Development and validation of a tool to assess emergency physicians’ nontechnical skills. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59(5):376–85.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mishra A, Catchpole K, McCulloch P. The Oxford NOTECHS system: reliability and validity of a tool for measuring teamwork behaviour in the operating theatre. BMJ Qual Saf. 2009;18(2):104–108. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2007.024760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frankel A, Gardner R, Maynard L, Kelly A. Using the communication and teamwork skills (CATS) assessment to measure health care team performance. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33(9):549–558. doi: 10.1016/S1553-7250(07)33059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guise JM, Deering SH, Kanki BG, Osterweil P, Li H, Mori M, et al. Validation of a tool to measure and promote clinical teamwork. Simulation in healthcare: journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare. 2008;3(4):217–223. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e31816fdd0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flin R, Martin L. Behavioral markers for crew resource management: a review of current practice. Int J Aviat Psychol. 2001;11(1):95–118. doi: 10.1207/S15327108IJAP1101_6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kines P, Andersen LP, Spangenberg S, Mikkelsen KL, Dyreborg J, Zohar D. Improving construction site safety through leader-based verbal safety communication. J Saf Res. 2010;41(5):399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fernandez R, Kozlowski SW, Shapiro MJ, Salas E. Toward a definition of teamwork in emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(11):1104–1112. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mitchell L, Flin R. Non-technical skills of the operating theatre scrub nurse: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2008;63(1):15–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ottestad E, Boulet JR, Lighthall GK. Evaluating the management of septic shock using patient simulation. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(3):769–775. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000256849.75799.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mickan SM, Rodger SA. Effective health care teams: a model of six characteristics developed from shared perceptions. Journal of interprofessional care. 2005;19(4):358–370. doi: 10.1080/13561820500165142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boreham N, Shea C, Mackway-Jones K. Clinical risk and collective competence in the hospital emergency department in the UK. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(1):83–91. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00441-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cosby KS, Roberts R, Palivos L, Ross C, Schaider J, Sherman S, et al. Characteristics of patient care management problems identified in emergency department morbidity and mortality investigations during 15 years. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51(3):251–61. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.06.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kachalia A, Gandhi TK, Puopolo AL, Yoon C, Thomas EJ, Griffey R, et al. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the emergency department: a study of closed malpractice claims from 4 liability insurers. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(2):196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaissi A, Johnson T, Kirschbaum MS. Measuring teamwork and patient safety attitudes of high-risk areas. Nurs Econ. 2003;21(5):211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schenkel SM, Khare RK, Rosenthal MM, Sutcliffe KM, Lewton EL. Resident perceptions of medical errors in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(12):1318–1324. doi: 10.1197/S1069-6563(03)00559-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stella D, Hendrie J, Smythe J, Graham I. Critical incident monitoring is a useful quality improvement tool for the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Australasia. 1996;8(4):215–219. [Google Scholar]

- 54.White AA, Wright SW, Blanco R, Lemonds B, Sisco J, Bledsoe S, et al. Cause-and-effect analysis of risk management files to assess patient care in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(10):1035–1041. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Senior B, Swailes S. Inside management teams: developing a teamwork survey instrument. Br J Manag. 2007;18(2):138–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8551.2006.00507.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Malec JF, Torsher LC, Dunn WF, Wiegmann DA, Arnold JJ, Brown DA, et al. The mayo high performance teamwork scale: reliability and validity for evaluating key crew resource management skills. Simul Healthc. 2007;2(1):4–10. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e31802b68ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morgan PJ, Pittini R, Regehr G, Marrs C, Haley MF. Evaluating teamwork in a simulated obstetric environment. Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. 2007;106(5):907–915. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000265149.94190.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cooper S, O’carroll J, Jenkin A, Badger B. Collaborative practices in unscheduled emergency care: role and impact of the emergency care practitioner—qualitative and summative findings. Emerg Med J. 2007;24(9):625–629. doi: 10.1136/emj.2006.043943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Apker J, Mallak LA, Gibson SC. Communicating in the “gray zone”: perceptions about emergency physician–hospitalist handoffs and patient safety. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(10):884–894. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blake RR, Mouton JS. Grid® principles versus Situationalism: a final note. Group & Organization Studies. 1982;7(2):211–215. doi: 10.1177/105960118200700208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cook DA, Beckman TJ. Does scale length matter? A comparison of nine-versus five-point rating scales for the mini-CEX. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2009;14(5):655. doi: 10.1007/s10459-008-9147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martuza VR. Applying norm-referenced and criterion-referenced measurement in education: Allyn & Bacon, Incorporated; 1977.

- 63.Hitzier R, Honer A, Maeder C. Die institutionalisierte Kompetenz zur Konstruktion von Wirklichkeit.

- 64.Asbury J-E. Overview of focus group research. Qual Health Res. 1995;5(4):414–420. doi: 10.1177/104973239500500402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Basch CE. Focus group interview: an underutilized research technique for improving theory and practice in health education. Health Educ Q. 1987;14(4):411–448. doi: 10.1177/109019818701400404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Morgan D. The focus group guidebook: sage publications. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pelz C, Schmitt A, Meis M, editors. Knowledge Mapping als Methode zur Auswertung und Ergebnispräsentation von Fokusgruppen in der Markt-und Evaluationsforschung. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research; 2004: Deutschland.

- 68.Bogner A, Littig B, Menz W. Introduction: expert interviews—an introduction to a new methodological debate. Interviewing experts: Springer. 2009. pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jun M, Peterson RT, Zsidisin GA. The identification and measurement of quality dimensions in health care: focus group interview results. Health Care Manag Rev. 1998;23(4):81–96. doi: 10.1097/00004010-199810000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dorussen H, Lenz H, Blavoukos S. Assessing the reliability and validity of expert interviews. European Union Politics. 2005;6(3):315–337. doi: 10.1177/1465116505054835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zwick Michael M., Schröter Regina. Fokusgruppen in der empirischen Sozialwissenschaft. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2012. Konzeption und Durchführung von Fokusgruppen am Beispiel des BMBF-Projekts „Übergewicht und Adipositas bei Kindern, Jugendlichen und jungen Erwachsenen als systemisches Risiko“; pp. 24–48. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Abell N, Springer DW, Kamata A. Developing and validating rapid assessment instruments. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stewart GL, Barrick MR. Team structure and performance: assessing the mediating role of intrateam process and the moderating role of task type. Acad Manag J. 2000;43(2):135–148. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sevdalis N, Hull L, Birnbach D. Improving patient safety in the operating theatre and perioperative care: obstacles, interventions, and priorities for accelerating progress. Br J Anaesth. 2012;109:i3–i16. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goeters K-M. Evaluation of the effects of CRM training by the assessment of non-technical skills under LOFT. Human Factors and Aerospace Safety. 2002;2(1).

- 76.Polit DF, Beck CT, Owen SV. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2007;30(4):459–467. doi: 10.1002/nur.20199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

AS-NTS. (DOCX 93 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.