Key Points

Question

What are the functional and structural changes over time of patients with rod-cone dystrophy harboring mutations in PDE6A and PDE6B?

Findings

In this cohort, longitudinal, follow-up study of 54 patients with rod-cone dystrophy and mutations in PDE6A or PDE6B, progressive photoreceptor degeneration was documented. The findings reveal a similar disease course between both genetic groups with preservation of functional visual abilities at older ages.

Meaning

The results of this study suggest that these functional and structural findings may enable a better prognostic estimation and candidate selection for photoreceptor therapeutic rescue.

Abstract

Importance

A precise phenotypic characterization of retinal dystrophies is needed for disease modeling as a basis for future therapeutic interventions.

Objective

To compare genotype, phenotype, and structural changes in patients with rod-cone dystrophy (RCD) associated with mutations in PDE6A or PDE6B.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In a retrospective cohort study conducted in Paris, France, from January 2007 to September 2017, 54 patients from a cohort of 1095 index patients with RCD underwent clinical examination, including personal and familial history, best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), color vision, slitlamp examination, full-field electroretinography, kinetic visual fields (VFs), retinophotography, optical coherence tomography, near-infrared fundus autofluorescence, and short-wavelength fundus autofluorescence imaging. Genotyping was performed using microarray analysis, targeted next-generation sequencing, and Sanger sequencing validation with familial segregation when possible. Data were analyzed from September 1, 2017, to February 1, 2018. Clinical variables were subsequently analyzed in 2018.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Phenotype and genotype comparison of patients carrying mutations in PDE6A or PDE6B.

Results

Of the 54 patients included in the study, 19 patients of 17 families (11 women [58%]; mean [SD] age at diagnosis, 14.83 [10.63] years) carried pathogenic mutations in PDE6A, and 35 patients of 26 families (17 women [49%]; mean [SD] age at diagnosis, 21.10 [11.56] years) had mutations in PDE6B, accounting for prevalences of 1.6% and 2.4%, respectively. Among 49 identified genetic variants, 14 in PDE6A and 15 in PDE6B were novel. Overall, phenotypic analysis revealed no substantial differences between the 2 groups except for night blindness as a presenting symptom that was noted to be more prevalent in the PDE6A than PDE6B group (80% vs 37%, respectively; P = .005). The mean binocular BCVA and VF decrease over time (measured as mean individual slopes coefficients) was comparable between patients with PDE6A and PDE6B mutations: 0.04 (0.12) vs 0.02 (0.05) for BCVA (P = .89) and 14.33 (7.12) vs 13.27 (6.77) for VF (P = .48).

Conclusions and Relevance

Mutations in PDE6A and PDE6B accounted for 1.6% and 2.4%, respectively, in a cohort of French patients with RCD. The functional and structural findings reported may constitute the basis of disease modeling that might be used for better prognostic estimation and candidate selection for photoreceptor therapeutic rescue.

This cohort study examines the differences over time between outcomes associated with rod-cone dystrophy in patients with PDE6A and PDE6B mutations.

Introduction

Rod-cone dystrophy (RCD), also known as retinitis pigmentosa (RP) (OMIM #268000), is the most common inherited retinal degeneration, usually inherited as a mendelian trait with a prevalence of 1:4500.1,2,3 Rod-cone dystrophy is genetically and clinically heterogeneous, typically characterized by night blindness, followed by photophobia, gradual visual field constriction, and eventually legal blindness in most severe cases.4 Ophthalmoscopically, RCD is typically characterized by narrowed retinal vessels, waxy optic disc appearance, and peripheral pigment migration resembling bone spicules. Rod-cone dystrophy can be restricted to the retina or be part of a syndrome in 20% to 30% of the cases, such as Usher syndrome combined with deafness, which is the most common form.5

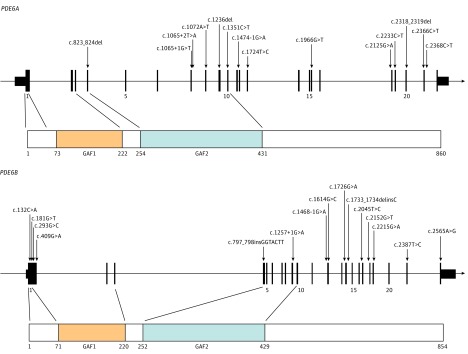

Genes associated with RCD exhibit various cellular functions and expression profiles. Among these, PDE6A (OMIM 180071)6 and PDE6B (OMIM 180072)6,7 encoding the rod-specific cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) phosphodiesterase α and β subunits, respectively, have a central role in the phototransduction cascade.8,9 Mutations in these genes account each for approximately 4% of autosomal-recessive RCD.10,11,12 PDE6A and PDE6B form a heterodimer inhibited by a homodimer composed of 2 γ subunits, encoded by PDE6G. Both PDE6A and PDE6B have 2 putative, noncatalytic domains (GAF1 and GAF2 [cGMP-specific phosphodiesterases, adenylyl cyclases, and formate hydrogenlyase transcriptional activator]), in the N-terminus, which binds cGMP and the polycationic region of 2 γ subunits in the inhibitory state of the complex (Figure 1).13 The C-terminal 250-residue catalytic domain binds guanine nucleotides and magnesium and undergoes posttranslational processing involving lipidation, proteolysis, and carboxymethylation.14

Figure 1. All Novel Mutations in PDE6A and PDE6B Identified in This Study.

The genomic sequence of PDE6A (A) and PDE6B (B) is presented above with protein domains below. Catalytic domains cyclic guanosine monophosphate–specific phosphodiesterases, adenylyl cyclases, and formate hydrogenlyase transcriptional activator FhlA; GAF1 and GAF2 are indicated. Nucleotide numbering is based on complementary DNA sequence of PDE6A refseq NM_000440.2 and NM_000283.3 for PDE6B where A of the ATG initiation codon is 1.

Light-induced activation of the PDE6 complex involves a G-protein (transducin)–mediated displacement of γ subunits leading to cGMP hydrolysis, closure of a transmembrane cGMP-gated cationic channel, and rod photoreceptor hyperpolarization.8 Mutations in PDE6A or PDE6B produce an increase in intracellular cGMP triggering cell death most likely through a calcium/sodium imbalance.15 The activation of a cGMP-dependent protein kinase G may also contribute to cGMP-induced photoreceptor death.16 Several animal models harboring mutations in PDE6A17,18,19 and PDE6B, including the widely used retinal degeneration 1 mice,20 retinal degeneration 10 mice,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 and PDE6A-mutated Cardigan Welsh corgi dogs27 are instrumental to elucidate pathophysiologic mechanisms and for preclinical therapeutic interventions.23,28,29,30,31,32,33

In this study, we identified patients with RCD carrying mutations in PDE6A or PDE6B from a large cohort of 1095 French patients with inherited retinal degeneration. Our aim was to document phenotypic characteristics, monitor retinal structural changes over time, and extract information for disease modeling relevant for prognosis and future therapies.

Methods

Clinical Investigation

Patients were clinically investigated at the National Reference Center for Rare Diseases of Quinze-Vingts Hospital, Paris, France. Ophthalmic examination was performed as previously described.34 All participants signed an informed consent form following explanation of the study and its potential outcome; there was no financial compensation. The study protocol adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki35 and was approved by the ethical Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile de France V.

Mutations Analysis

DNA samples were collected from affected and unaffected family members when possible.36 Microarray analysis (autosomal-recessive RP; Asper Ophthalmics) covering 490 known variants in 17 known genes was initially applied in 2007 with targeted Sanger sequencing in candidate genes (eg, EYS and exon 13 of USH2A).37 Targeted next-generation sequencing in 123 to 215 genes mutated in inherited retinal degeneration was subsequently performed.38,39 Variants' pathogenicity and conservation were evaluated as described in the eAppendix in the Supplement.

Clinical Data Collection

Clinical data were retrospectively collected from medical records. These included sex, age at time of diagnosis and examination, personal and familial history, symptoms, logMAR best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), refractive error, slitlamp biomicroscopy, Lanthony desaturated D-15 panel, Goldmann kinetic visual fields (VFs), full-field electroretinography, spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT), retinophotography, near-infrared fundus autofluorescence (NIRAF), and short-wavelength fundus autofluorescence (SWAF) imaging. Structural changes, including horizontal and vertical diameters through the fovea of the ellipsoid zone (EZ) on SD-OCT and hyperautofluorescent ring on SWAF and NIRAF, were measured using Heidelberg Eye Explorer, version 1.9.10.0 (Heidelberg Engineering) (eFigure 5 in the Supplement).

Statistical Analysis

Because no substantial difference in BCVA and VF was found between both eyes for both genotypic groups (eTable 7 in the Supplement), all variables were averaged between eyes, including BCVA and VF (BCVAou and VFou, respectively) and used for further analysis. Differences between both genotypic groups were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test.

Given the heterogeneity in the number of observations and follow-up visits for each patient, we estimated the rate of decline for both BCVAou and VFou using the slope of the regression line obtained plotting age against BCVA (logMAR) or VF (degrees) for each patient. The regression slopes were then compared between both genetic groups using the Mann-Whitney test. The same approach was used to estimate the rate of change for imaging variables (preserved EZ on SD-OCT and SWAF and NIRAF rings). For the comparison between horizontal and vertical diameters within each group, a Wilcoxon signed ranked test was performed.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted for BCVAou greater than 0.22 logMAR (0.60 Snellen equivalent) and greater than 0.52 logMAR (0.30 Snellen equivalent) and VFou greater than 20°. The difference between the curves from each genotypic group was determined using a log-rank test.

Pearson χ2 test was used to analyze the difference between PDE6A and PDE6B genotypic groups for all categorical variables. Clinical variables were analyzed using SPSS Statistics software, version 21.0 (IBM Inc), with P ≤ .05 considered statistically significant. Two-tailed, paired testing was performed for the Wilcoxon signed ranked test; 2-tailed, unpaired testing was performed for the statistical measures.

Results

Identification of Patients Harboring Mutations in PDE6A and PDE6B

Overall, the genetic screening of 1095 index cases with autosomal-recessive RCD identified 19 patients (17 families) and 35 patients (26 families) with biallelic mutations in PDE6A and PDE6B, respectively (eTables 1 and 2, 5 and 6 in the Supplement). This finding would therefore indicate a prevalence of 1.6% and 2.4% for mutations in PDE6A and PDE6B, respectively.

For PDE6A, a total of 21 mutations were identified of which 14 are novel spanning the entire protein except GAF1 domain (Figure 1), including 5 missense, 3 nonsense, 3 splice-site mutations, and 3 small deletions (eTables 1 and 3 in the Supplement). A total of 28 mutations were identified in PDE6B with 15 novel mutations spanning the entire protein (Figure 1), including 8 missense, 2 nonsense, 2 splice, 1 insertion, 1 insertion-deletion, and 1 change affecting the stop codon (eTables 2 and 4 in the Supplement).

Novel mutated amino acid residues in PDE6A and PDE6B were highly conserved among primates (eFigure 1 in the Supplement) and moderately to highly conserved among 100 species (eTables 3 and 4 in the Supplement, respectively). In the absence of functional analysis, the significance of missense mutations is uncertain.

Age at Time of Diagnosis and Presenting Symptoms

The clinical data for all patients with PDE6A and 34 of 35 patients with PDE6B mutations are summarized in eTables 5 and 6 in the Supplement, respectively. No statistically significant difference was found between the groups for sex (58% of the women [11 of 19] with PDE6A and 49% of the women [17 of 35] with PDE6B mutations ; P = .51) (Table 1) and age at diagnosis (mean [SD], 14.83 [10.63]; range, 5-42 years for PDE6A and 21.10 [11.56]; range, 3-45 years for PDE6B; P = .08). The mean age at the first visit with data available was 38 (15.13) years (range, 7-60 years) for PDE6A and 41.56 (12.73) years (range, 12-63 years) for PDE6B (P = .48). Night blindness was the most prevalent symptom for both groups at presentation, although it was more common in patients with PDE6A than PDE6B mutations (12 of 15 [80%] vs 13 of 35 [37%]; P = .005) (Table 1).

Table 1. Clinical Characteristics of Patients Harboring Mutations in PDE6A and PDE6B Genes.

| Characteristic | PDE6A | PDE6B | Mean Difference (95% CI) | P Value, PDE6A vs PDE6B |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female, No./total No. (%) | 11/19 (58) | 17/35 (49) | NA | .51a |

| Age at diagnosis, mean (SD) [range], y | n = 18 14.83 (10.63) [5-42] |

n = 28 21.10 (11.56) [3-45] |

−6.27 (−13 to 0.50) |

.08b |

| Age at first visit with available data, mean (SD) [range], y | n = 19 38 (15.13) [7-60] |

n = 33 41.56 (12.73) [12-63] |

−3.56 (−11.60 to 4.52) |

.48b |

| Follow-up for BCVA, No. | n = 19 Range, 0-42 y |

n = 34 Range, 0-28 y |

NA | |

| 0 y | 1 | 10 | NA | NA |

| 1-5 y | 10 | 7 | NA | NA |

| 6-10 y | 2 | 7 | NA | NA |

| 11-15 y | 2 | 8 | NA | NA |

| >15 y | 4 | 2 | NA | NA |

| First visit available BCVAou, logMAR (SD) [Snellen equivalent] |

n = 19 0.36 (0.52) [20/40] |

n = 34 0.40 (0.38) [20/50] |

−0.04 (−0.30 to 0.22) |

.28b |

| Estimation of BCVAou decline, mean regression slope (SD) |

n = 17 0.04 (0.12) |

n = 22 0.02 (0.05) |

0.014 (−0.04 to 0.07) |

.88b |

| Follow-up for VF, No. | n = 15 Range, 0-35 y |

n = 22 Range, 0-25 y |

NA | NA |

| 0 y | 5 | 10 | NA | NA |

| 1-5 y | 7 | 6 | NA | NA |

| 6-10 y | 2 | 3 | NA | NA |

| 11-15 y | 0 | 0 | NA | NA |

| >15 y | 1 | 3 | NA | NA |

| First visit with available data, VFou, mean (SD), degrees |

n = 15 14.33 (7.12) |

n = 22 13.27 (6.77) |

1.06 (−3.66 to 5.78) |

.67b |

| Estimation of VFou decline, mean regression slope (SD) |

n = 10 − 1.18 (1.55) | n = 11 − 0.736 (0.873) |

−0.44 (−1.59 to 0.71) |

.48b |

| Night blindness as presenting symptom, No./total No. (%) | 12/15 (80) | 13/35 (37) | NA | .005a |

| Binocular normal color vision, No./total No. (%) | 8/18 (44) | 11/29 (38) | NA | .66a |

| Cataract and/or previous cataract surgery in at least 1 eye, No./total No. (%) | 12/19 (63) | 23/29 (79) | NA | .22a |

| Bilateral undetectable ffERG, No./total No. (%) | 15/18 (83) | 30/34 (88) | NA | .62a |

| Preserved EZ and ONL, No./total No. (%) | 17/18 (94) | 25/32 (78) | NA | .13a |

| Monolateral or bilateral SD-OCT evidence-based CME, No./total No. (%) | 6/19 (32) | 9/32 (28) | NA | .79a |

| Monolateral or bilateral ERM, No./total No. (%) | 6/19 (32) | 10/32 (31) | NA | .98a |

Abbreviations: BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; BCVAou, mean BCVA between right and left eye; CME, cystoid macular edema; ERM, epiretinal membrane; EZ, ellipsoid zone; ffERG, full-field electroretinography; NA, not applicable; ONL, outer nuclear layer; SD-OCT, spectral-domain optical coherence tomography; VF, visual field; VFou, mean VF between right and left eye.

Pearson χ2 test.

Mann-Whitney test.

Visual Acuity Pattern of Change

Data on BCVA were available for at least 1 visit for all patients with PDE6A mutations and were missing for 1 patient with PDE6B mutations (eTables 1 and 2 in the Supplement). In the PDE6A group, mean BCVAou at the first examination was 0.36 (0.52) logMAR (Snellen equivalent: range, 0.01-1.00; median, 0.60). A total of 86 BCVA serial measurements were collected during the follow-up period (number of observations per patient: minimum 1, maximum 15).

In the PDE6B group, mean BCVAou at first examination was 0.40 (0.38) (Snellen equivalent: range, 0.01-1.25; median, 0.50). A total of 121 serial measurements were collected during the follow-up period (number of observations per patient: minimum, 1; maximum, 12).

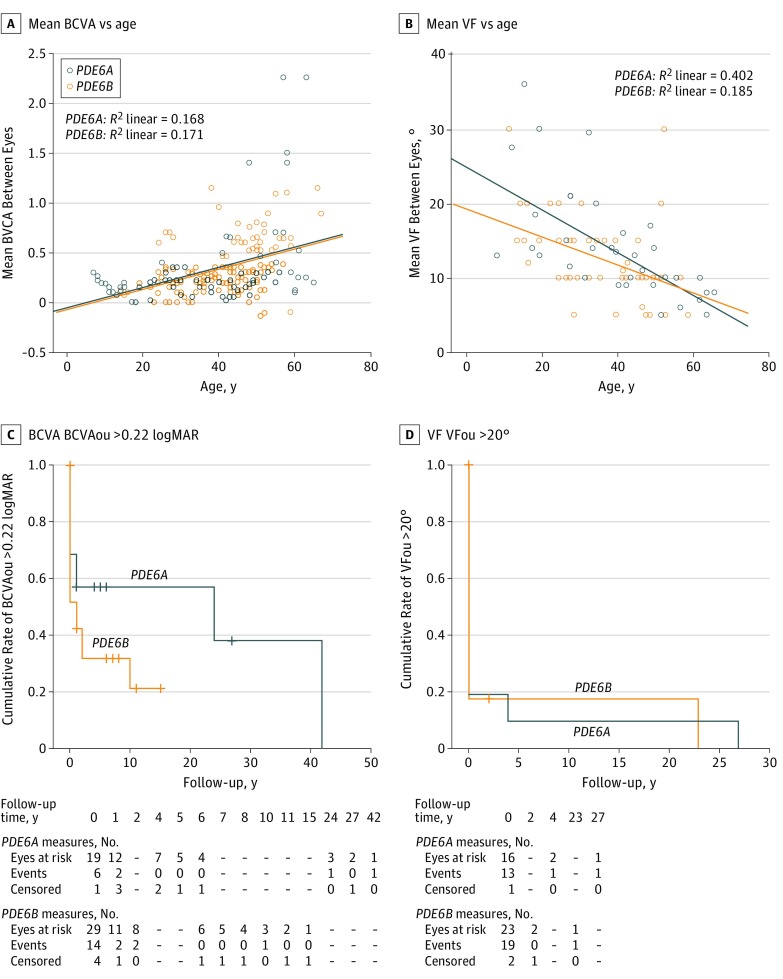

All BCVA measurements were plotted with age as presented in Figure 2A. The estimation of the rate of BCVAou decline using individual regression slopes revealed no statistically significant differences between both genotypic groups (P = .88) (Table 1).

Figure 2. Best-Corrected Visual Acuity (BCVA) and Visual Field (VF) Measures in Patients With PDE6A and PDE6B Mutations .

A, logMAR BCVA vs age. B, VF vs age. All serial measurements collected for all patients were included. C, logMAR BCVA analysis for mean BCVA between right and left eye (BCVAou) greater than 0.22 vs follow-up time. D, Central mean VF between right and left eye (VFou) greater than 20° vs follow-up time. Dashes indicate missing data at those time points.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing the survival distribution of BCVAou greater than 0.22 logMAR (0.60 Snellen equivalent) and BCVAou greater than 0.52 logMAR (0.30 Snellen equivalent) were not statistically significantly different between both genotypic groups (P = .19 and P = .40 respectively) (Figure 2C and eFigure 3 in the Supplement). More than 50% of the patients with PDE6A mutations (n=10) preserved a BCVAou greater than 0.22 logMAR and more than 70% (n=14) preserved a BCVAou greater than 0.52 logMAR 20 years after the initial RCD diagnosis. In the PDE6B group, more than 30% of the patients (n=11) preserved a BCVAou greater than 0.22 logMAR and 60% (n=21) preserved a BCVAou greater than 0.52 logMAR 10 years after the initial diagnosis (Figure 2C and eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

Abnormal Color Vision

Data on Lanthony desaturated D-15 panel color vision testing were available for 18 of 19 patients (95%) with PDE6A mutations and 27 of 35 patients (77%) with PDE6B mutations. Color vision was within the reference range in both eyes in 44% and in 38% of patients with PDE6A and PDE6B mutations (P = .66), respectively (eTables 5 and 6 in the Supplement), with the tritan defect being the most common alteration. No clear correlation was found between BCVA and color vision defect at presentation for both groups.

VF Pattern of Change

All patients carrying PDE6A mutations and 29 of 35 patients (83%) carrying PDE6B mutations had at least 1 VF examination performed for both eyes (eTables 1 and 2 in the Supplement). At the first available visit, VFou values were 14.33° (7.12°) and 13.27° (6.77°) for PDE6A and PDE6B, respectively (P = .67) (Table 1).

Using all observations available (number of observations per PDE6A patients: minimum 1, maximum 6; number of observations per PDE6B patients: minimum 1, maximum 8), VFou was plotted and correlated with age in both genotypic groups using the scatterplots displayed in Figure 2B. The estimation of the rate of VFou decline using individual regression slopes revealed no statistically significant differences between the PDE6A and PDE6B genotypic groups (−1.18 [1.55] vs −0.74 [0.87]; P = .48) (Table 1).

Kaplan-Meier survival curves show the survival distribution of VFou greater than 20 central degrees in more than 80% of the patients before 5 years from disease presentation in both genotypic groups (P = .92) (Figure 2D).

Electroretinography Responses

Full-field electroretinography data were available for 18 of 19 patients (95%) with PDE6A mutations and 34 of 35 patients (97%) with PDE6B mutations. Responses were undetectable for both scotopic and photopic conditions in 15 (83%) and 30 (88%) patients carrying mutations in PDE6A and PDE6B (P = .62), respectively (Table 1).

Ocular Findings

Slitlamp examination was unremarkable other than cataracts. Posterior subcapsular cataract or previous cataract surgery at presentation were present in 12 (63%) and 23 (79%) patients with PDE6A and PDE6B mutations, respectively (P = .22) (Table 1 and eTables 5 and 6 in the Supplement). Fundoscopy for both groups revealed typical changes in keeping with RCD and relative foveal sparing (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). The severity of these alterations correlated with age. Three patients with PDE6B mutations presented with peripheral pigmentary clumps, but none had bone spicules inside the vascular arcades. Narrowed retinal vessels and waxy disc pallor were noticed in 14 of 18 patients (78%) with PDE6A mutations and 16 of 34 patients (47%) with PDE6B mutations (eFigure 2 and eTables 5 and 6 in the Supplement).

SWAF, NIRAF, and SD-OCT Alterations

SWAF revealed a ring of increased autofluorescence surrounding the fovea in 13 of 19 patients (68%) with PDE6A mutations and 24 of 32 patients (75%) with PDE6B mutations. This ring corresponded to the leading border of the progressive peripheral outer retinal thinning surrounding an area of preserved hyperreflective outer retinal bands centrally on SD-OCT (eFigure 2 and eTables 5 and 6 in the Supplement). Peripheral autofluorescence results were abnormal in all patients following various patterns (ie, patches, dots, blots, or mixed) (eFigure 2 and eTables 5 and 6 in the Supplement). NIRAF showed a normal, well-defined area of preserved autofluorescence centrally in both eyes surrounded by reduced autofluorescence corresponding to the outer retinal thinning on SD-OCT in 13 of 17 patients (76%) with PDE6A mutations and in 20 of 26 patients (77%) with PDE6B mutations (eFigure 2 and eTables 5 and 6 in the Supplement). Horizontal cross sections of SD-OCT showed preservations of the outer retinal hyperreflective bands, including the EZ and interdigitation zones, as well as the outer nuclear layer in 17 of 18 patients (94%) with PDE6A mutations and 25 of 32 patients (78%) with PDE6B mutations (P = .13) surrounded by an area with altered hyperreflective bands compatible with outer retinal atrophy.

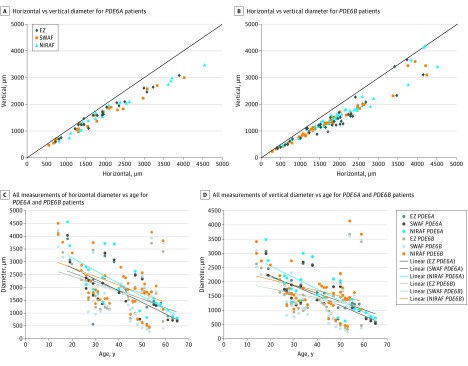

Longitudinal Multimodal Imaging Changes

Ten of 20 patients (50%) with PDE6A mutations and 16 of 35 patients (46%) with PDE6B mutations had at least 1 complete set of SD-OCT, SWAF, and NIRAF data for both eyes. For the 3 imaging modalities, longitudinal measurements determined at different ages of the participants consistently showed a larger horizontal than vertical diameter for both the PDE6A and PDE6B groups following an ellipsoid shape (Table 2 and eFigure 2 in the Supplement). This preserved area tends to adopt a circular shape for smaller-diameter measurements: less than 2000 μm for PDE6A and less than 1500 μm for PDE6B (Figure 3A, upper raw panels and eFigures 2-4 in the Supplement). This finding suggests that the preserved retinal area progresses from ellipsoid to circular shape in advanced stages of the disease. Both horizontal and vertical diameters of the preserved EZ, SWAF, and NIRAF were correlated with age for both genotypic groups (scatterplots in Figure 2B and eFigure 6A and B in the Supplement).

Table 2. Mean Percentage of Horizontal and Vertical Annual Constriction Ellipsoid Zone, SWAF, and NIRAF Diameters.

| Measure | PDE6A (n = 8) | PDE6B (n = 11) | PDE6A vs PDE6B | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation of Reduction, Mean Regression Slope (SD) | Difference (95% CI), P Valuea | Estimation of Reduction, Mean Regression Slope (SD) | Difference (95% CI) P Valuea |

Estimated Horizontal Reduction Difference, (95% CI), P Valueb | Estimated Vertical Reduction Difference, (95% CI), P Valueb | |||

| Horizontal | Vertical | Horizontal | Vertical | |||||

| Ellipsoid zone | −55.87 (35.25) | −26.92 (22.9 2) | −28.95 (−58.10 to 0.20), P = .36 | −81.49 (53.08) | −46.15 (33.23) | −35.34 (−74.72 to 4.04), P = .003 | 26.62 (−18.55 to 69.80), P = .35 | 19.23 (−8.75 to 47.21), P = .24 |

| SWAF | −51.19 (39.21) | −40.19 (25.71) | −11.00 (−43.50 to 21.50), P = .40 | −73.40 (37.23) | −47.98 (28.60) | −25.42 (−54.95 to 4.10), P = .01 | 22.21 (−15.27 to 59.70), P = .27 | 7.79 (−18.87 to 34.45), P = .83 |

| NIRAF | −58.81 (32.8) | −49.88 (32.64) | −8.93 (−44.00 to 26.16), P = .40 | −89.0 (59.12) | −58.16 (27.43) | −30.84 (−71.83 to 10.15), P = .07 | 30.19 (−16.68 to 77.06), P = .48 | 8.28 (−21.27 to 37.84), P = .36 |

Abbreviations: NIRAF, near-infrared fundus autofluorescence; SWAF, short-wavelength fundus autofluorescence.

P values determined using Wilcoxon signed ranked test.

P values determined using Mann-Whitney test.

Figure 3. Longitudinal Structural Changes of Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography (SD-OCT), Short-Wavelength Fundus Autofluorescence (SWAF), and Near-Infrared Fundus Autofluorescence (NIRAF) Images of Patients With PDE6A and PDE6B Mutations.

Horizontal and vertical diameters measured for ellipsoid zone (EZ), inner SWAF, and outer hyperautofluorescent parafoveal rings in patients with PDE6A (A) and PDE6B (B) mutations showing that the vertical diameter is smaller than the horizontal diameter and becoming equal with degeneration progression. All SD-OCT, SWARF, and NIRAF horizontal (C) and vertical (D) measurements of both groups plotted on the same chart show measurements within comparable ranges and clustering into parallel trend lines.

The rate of change in horizontal and vertical diameters of the EZ preservation area, as well as SWAF and NIRAF rings, were estimated using the individual regression slopes of each participant with at least 2 available SD-OCTs. Eight (42%) and 11 (31%) patients were available for this analysis for PDE6A and PDE6B, respectively. A statistically significant difference was found between the rate of change of horizontal against vertical diameters of the preserved EZ (−81.49 [53.08] and −46.15 [33.23], respectively, P < .01) and SWAF (73.40 [37.23] and −47.98 [28.60] respectively, P = .01) in the PDE6B group, possibly confirming the hypothesis of a gradual circularization of the shape of the preserved area.

Discussion

Our study analyzed genotype and phenotype correlation in autosomal-recessive RCD associated with mutations in PDE6A or PDE6B from a cohort of 1095 inherited retinal degeneration index cases. We established a prevalence of 1.6% for PDE6A mutations in keeping with previous reports of 1.15% (2 of 173 families)6 and 3.65% (6 of 164 families).10 PDE6B mutations accounted for 2.4% of RCD in our study; 3.0% to 4.5% (92 comprehensively and 50 partially screened families)11 and 16% (3 of 19 families) were reported in North American patients with RP.12 This variability may be attributed to variable cohort sizes and distinct founder mutations. In comparison, mutations in USH2A account for the most common cause of autosomal-recessive RCD (7%-13.5%),40,41 followed by EYS (4.7%-12%)37,42 in Europe and America, whereas both gene defects account for 9% (11 of 121) and 29% (35 of 121) in Japan, respectively.43

We identified a total of 49 variants including 14 novel variants in PDE6A and 15 novel variants in PDE6B spanning the different functional domains of the proteins expanding their mutations spectrum (Figure 1 and eTables 1-4 in the Supplement). Several changes were recurrent in unrelated families, including c.1705C>A, c.304C>A in PDE6A and c.1010A>G and c.1107+3A>G in PDE6B, that may represent founder mutations. Novel mutations are expected to affect protein function either modifying the GAF domains; residues involved with interacting partners, such as Pγ,44 lead to a truncated protein lacking the cGMP binding sites and/or alter its subcellular localization or an absence of proteins through nonsense-mediated decay and loss of function.45,46

With PDE6A and PDE6B being interacting proteins within the PDE6 complex,47 conceivably, mutations in both proteins cause similar phenotypes. We demonstrated that both genetic groups lead to classic RCD with night blindness and progressive visual field constriction, but with relatively preserved central vision at older ages. The findings suggest that more than 50% of patients with PDE6A mutations and 30% of patients with PDE6B mutations preserve a BCVA of 0.60 or more 20 years after the initial diagnosis. This level is better than in patients with CRB1 mutations, among whom 50% have a BCVA of 0.30 or lower at age 18 years and 0.10 or lower at age 35 years,48 or heterogeneous genetic groups shown to progress from 0.50 to 0.10 within 6 years from diagnosis.49 Estimated mean rate of BCVA decline, based on the regression slope of each patient, was comparable (0.037 [0.12] and 0.023 [0.046] for PDE6A and PDE6B mutations, respectively). Previous studies report annual decline rates of 1%,50 2%,51 and 8.6%52 for RCD overall, and 1.8% for ADRCD (autosomal dominant RCD) caused by RHO mutations.53

Our VF decline rate did not differ significantly between patients with PDE6A and PDE6B mutations (target III1e), with both groups maintaining a central VF of 5° to 10° up to age 60 years. Previous reports document an annual decline of 4.6% (target V4e),50 9.1% (target II4e),54 and 12% (V4e target)51 for RCD overall, and 2.6% (target V4e) for ADRCD caused by RHO mutations.53 Furthermore, for this factor, the methodologic heterogeneity among studies makes a direct comparison of the results impossible.

Structural changes shown using SWAF, NIRAF, and SD-OCT were in keeping with RCD and relative central sparing. A correlation was found between the horizontal and vertical diameters of preserved EZ, SWAF inner-ring diameter, and NIRAF outer-ring diameter in both genetic groups.55 The vertical diameter was consistently smaller than the horizontal diameter in the 3 imaging modalities,56,57,58 which may be explained by anatomic, histologic, or physiologic differences, such as variation in cone density59 and spacing.60 Nevertheless, our data suggest a faster constriction of the horizontal than the vertical diameter, which may account for the circularization of the spared ring shape in the late phases of the disease.

In contrast to previous reports,55 a qualitative analysis of the scatterplots of age vs SWAF or NIRAF rings (Figure 3B and eFigure 6A and B in the Supplement) may suggest a correlation between the ring diameters and age. This discrepancy may be derived from 2 factors: the clinical and genetic heterogeneity of previous reports and the inclusion of serial repeated measurements in our analysis. The prevalence of intraretinal cysts and epiretinal membrane was similar to that in previous reports.61,62

Limitations and Strengths

Our study has several limitations, including its retrospective design (with potential selection bias) and the relatively small sample size (primarily for the longitudinal analysis), which could have affected the statistics. The correlations between BCVA and VF with age was performed using only scatterplots, not providing statistical value, because the results could have been affected by the inclusion of all serial repeated measurements. Prospective longitudinal studies including larger cohorts would be needed to confirm our findings.

However, our study has strengths. Even if the number of patients included was too small to ensure a strong statistical analysis, it is a large cohort considering the prevalence of the disease and, above all, of the PDE6A and PDE6B mutations in the population.

Conclusions

Our study appears to expand the mutations spectrum in PDE6A and PDE6B and outlines the classic autosomal-recessive RCD phenotype with preservation of macular cones over the course of the disorder. These findings may provide a basis for disease modeling used in the design of clinical trials aiming to promote cone survival.

eAppendix. Study Details

eFigure 1. Conservation of Novel Missense Mutated Amino Acids or Splicing Sites for PDE6A and PDE6B Genes

eFigure 2. Fundus Color, Short-Wavelength (SWAF) and Near-Infrared (NIRAF) Autofluorescence and SD-OCT Horizontal Cross-Section Photos of Patients Harboring Mutations in PDE6A And PDE6B at Different Ages

eFigure 3. Kaplan-Meier Analyses of BCVA of PDE6A- and PDE6B-Mutated Patients

eFigure 4. Serial Measurements of BCVA and VF With Parallel SD-OCT, SWAF and NIRAF Images for CIC04774- PDE6A and CIC05351-PDE6B Patients

eFigure 5. Measurements of Structural Changes

eFigure 6. Longitudinal Structural Changes of SD-OCT, SWAF and NIRAF Images of PDE6A- and PDE6B-Mutated Patients

eTable 1. Patients With PDE6A Mutations Identified in This Study With In Silico Analysis of the Variants

eTable 2. Patients With PDE6B Mutations Identified in this Study With In Silico Analysis on Variants

eTable 3. List of Mutations Identified in PDE6A in Our Cohort

eTable 4. List of Mutations Identified in PDE6B in Our Cohort

eTable 5. Clinical Data of Patients Harboring PDE6A Mutations

eTable 6. Clinical Data of Patients Harboring PDE6B Mutations

eTable 7. BCVA, VF and Imaging Data From Both Eyes of the Patients in Both Genetic Cohorts

References

- 1.Bundey S, Crews SJ. A study of retinitis pigmentosa in the City of Birmingham—II: clinical and genetic heterogeneity. J Med Genet. 1984;21(6):421-428. doi: 10.1136/jmg.21.6.421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bunker CH, Berson EL, Bromley WC, Hayes RP, Roderick TH. Prevalence of retinitis pigmentosa in Maine. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984;97(3):357-365. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(84)90636-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg T. Epidemiology of hereditary ocular disorders. Dev Ophthalmol. 2003;37:16-33. doi: 10.1159/000072036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berson EL. Retinitis pigmentosa: the Friedenwald Lecture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34(5):1659-1676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartong DT, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet. 2006;368(9549):1795-1809. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69740-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang SH, Pittler SJ, Huang X, Oliveira L, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa caused by mutations in the alpha subunit of rod cGMP phosphodiesterase. Nat Genet. 1995;11(4):468-471. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLaughlin ME, Sandberg MA, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Recessive mutations in the gene encoding the beta-subunit of rod phosphodiesterase in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Nat Genet. 1993;4(2):130-134. doi: 10.1038/ng0693-130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arshavsky VY, Lamb TD, Pugh EN Jr. G proteins and phototransduction. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:153-187. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.082701.102229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu Y, Yau KW. Phototransduction in mouse rods and cones. Pflugers Arch. 2007;454(5):805-819. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0194-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dryja TP, Rucinski DE, Chen SH, Berson EL. Frequency of mutations in the gene encoding the alpha subunit of rod cGMP-phosphodiesterase in autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40(8):1859-1865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLaughlin ME, Ehrhart TL, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Mutation spectrum of the gene encoding the beta subunit of rod phosphodiesterase among patients with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(8):3249-3253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danciger M, Heilbron V, Gao YQ, Zhao DY, Jacobson SG, Farber DB. A homozygous PDE6B mutation in a family with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Vis. 1996;2:10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muradov KG, Granovsky AE, Schey KL, Artemyev NO. Direct interaction of the inhibitory gamma-subunit of rod cGMP phosphodiesterase (PDE6) with the PDE6 GAFa domains. Biochemistry. 2002;41(12):3884-3890. doi: 10.1021/bi015935m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ong OC, Ota IM, Clarke S, Fung BK. The membrane binding domain of rod cGMP phosphodiesterase is posttranslationally modified by methyl esterification at a C-terminal cysteine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(23):9238-9242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doonan F, Donovan M, Cotter TG. Activation of multiple pathways during photoreceptor apoptosis in the rd mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(10):3530-3538. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang T, Tsang SH, Chen J. Two pathways of rod photoreceptor cell death induced by elevated cGMP. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26(12):2299-2306. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuntivanich N, Pittler SJ, Fischer AJ, et al. . Characterization of a canine model of autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa due to a PDE6A mutation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(2):801-813. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakamoto K, McCluskey M, Wensel TG, Naggert JK, Nishina PM. New mouse models for recessive retinitis pigmentosa caused by mutations in the Pde6a gene. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(1):178-192. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sothilingam V, Garcia Garrido M, Jiao K, et al. . Retinitis pigmentosa: impact of different Pde6a point mutations on the disease phenotype. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(19):5486-5499. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hart AW, McKie L, Morgan JE, et al. . Genotype-phenotype correlation of mouse Pde6b mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(9):3443-3450. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang B, Hawes NL, Hurd RE, Davisson MT, Nusinowitz S, Heckenlively JR. Retinal degeneration mutants in the mouse. Vision Res. 2002;42(4):517-525. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6989(01)00146-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farber DB, Danciger JS, Aguirre G. The beta subunit of cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase mRNA is deficient in canine rod-cone dysplasia 1. Neuron. 1992;9(2):349-356. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90173-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett J, Tanabe T, Sun D, et al. . Photoreceptor cell rescue in retinal degeneration (rd) mice by in vivo gene therapy. Nat Med. 1996;2(6):649-654. doi: 10.1038/nm0696-649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao L, Zabel MK, Wang X, et al. . Microglial phagocytosis of living photoreceptors contributes to inherited retinal degeneration. EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7(9):1179-1197. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201505298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowes C, Li T, Danciger M, Baxter LC, Applebury ML, Farber DB. Retinal degeneration in the rd mouse is caused by a defect in the beta subunit of rod cGMP-phosphodiesterase. Nature. 1990;347(6294):677-680. doi: 10.1038/347677a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pittler SJ, Baehr W. Identification of a nonsense mutation in the rod photoreceptor cGMP phosphodiesterase beta-subunit gene of the rd mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(19):8322-8326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petersen-Jones SM, Entz DD, Sargan DR. cGMP phosphodiesterase-alpha mutation causes progressive retinal atrophy in the Cardigan Welsh corgi dog. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40(8):1637-1644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frasson M, Sahel JA, Fabre M, Simonutti M, Dreyfus H, Picaud S. Retinitis pigmentosa: rod photoreceptor rescue by a calcium-channel blocker in the rd mouse. Nat Med. 1999;5(10):1183-1187. doi: 10.1038/13508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tao W, Wen R, Goddard MB, et al. . Encapsulated cell-based delivery of CNTF reduces photoreceptor degeneration in animal models of retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43(10):3292-3298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Léveillard T, Mohand-Saïd S, Lorentz O, et al. . Identification and characterization of rod-derived cone viability factor. Nat Genet. 2004;36(7):755-759. doi: 10.1038/ng1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Komeima K, Rogers BS, Campochiaro PA. Antioxidants slow photoreceptor cell death in mouse models of retinitis pigmentosa. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213(3):809-815. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar-Singh R, Farber DB. Encapsidated adenovirus mini-chromosome–mediated delivery of genes to the retina: application to the rescue of photoreceptor degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7(12):1893-1900. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.12.1893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahashi M, Miyoshi H, Verma IM, Gage FH. Rescue from photoreceptor degeneration in the rd mouse by human immunodeficiency virus vector–mediated gene transfer. J Virol. 1999;73(9):7812-7816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Audo I, Friedrich A, Mohand-Saïd S, et al. . An unusual retinal phenotype associated with a novel mutation in RHO. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(8):1036-1045. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Audo I, Lancelot ME, Mohand-Saïd S, et al. . Novel C2orf71 mutations account for ∼1% of cases in a large French arRP cohort. Hum Mutat. 2011;32(4):E2091-E2103. doi: 10.1002/humu.21460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Audo I, Sahel JA, Mohand-Saïd S, et al. . EYS is a major gene for rod-cone dystrophies in France. Hum Mutat. 2010;31(5):E1406-E1435. doi: 10.1002/humu.21249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boulanger-Scemama E, El Shamieh S, Démontant V, et al. . Next-generation sequencing applied to a large French cone and cone-rod dystrophy cohort: mutation spectrum and new genotype-phenotype correlation. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:85. doi: 10.1186/s13023-015-0300-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Audo I, Bujakowska KM, Léveillard T, et al. . Development and application of a next-generation-sequencing (NGS) approach to detect known and novel gene defects underlying retinal diseases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:8. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-7-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seyedahmadi BJ, Rivolta C, Keene JA, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Comprehensive screening of the USH2A gene in Usher syndrome type II and non-syndromic recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Exp Eye Res. 2004;79(2):167-173. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glöckle N, Kohl S, Mohr J, et al. . Panel-based next generation sequencing as a reliable and efficient technique to detect mutations in unselected patients with retinal dystrophies. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22(1):99-104. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Littink KW, van den Born LI, Koenekoop RK, et al. . Mutations in the EYS gene account for approximately 5% of autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa and cause a fairly homogeneous phenotype. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(10):2026-2033, 2033.e1-2033.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oishi M, Oishi A, Gotoh N, et al. . Comprehensive molecular diagnosis of a large cohort of Japanese retinitis pigmentosa and Usher syndrome patients by next-generation sequencing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(11):7369-7375. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cote RH. Cyclic guanosine 5′-monophosphate binding to regulatory GAF domains of photoreceptor phosphodiesterase. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;307:141-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manes G, Cheguru P, Majumder A, et al. . A truncated form of rod photoreceptor PDE6 β-subunit causes autosomal dominant congenital stationary night blindness by interfering with the inhibitory activity of the γ-subunit. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e95768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muradov KG, Granovsky AE, Artemyev NO. Mutation in rod PDE6 linked to congenital stationary night blindness impairs the enzyme inhibition by its gamma-subunit. Biochemistry. 2003;42(11):3305-3310. doi: 10.1021/bi027095x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muradov H, Boyd KK, Artemyev NO. Rod phosphodiesterase-6 PDE6A and PDE6B subunits are enzymatically equivalent. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(51):39828-39834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.170068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mathijssen IB, Florijn RJ, van den Born LI, et al. . Long-term follow-up of patients with retinitis pigmentosa type 12 caused by CRB1 mutations: a severe phenotype with considerable interindividual. Retina. 2017;37(1):161-172. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marmor MF. Visual loss in retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;89(5):692-698. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(80)90289-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berson EL, Sandberg MA, Rosner B, Birch DG, Hanson AH. Natural course of retinitis pigmentosa over a three-year interval. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;99(3):240-251. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(85)90351-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holopigian K, Greenstein V, Seiple W, Carr RE. Rates of change differ among measures of visual function in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology. 1996;103(3):398-405. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(96)30679-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Birch DG, Anderson JL, Fish GE. Yearly rates of rod and cone functional loss in retinitis pigmentosa and cone-rod dystrophy. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(2):258-268. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90064-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berson EL, Rosner B, Weigel-DiFranco C, Dryja TP, Sandberg MA. Disease progression in patients with dominant retinitis pigmentosa and rhodopsin mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43(9):3027-3036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grover S, Fishman GA, Anderson RJ, Alexander KR, Derlacki DJ. Rate of visual field loss in retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(3):460-465. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(97)30291-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Robson AG, Tufail A, Fitzke F, et al. . Serial imaging and structure-function correlates of high-density rings of fundus autofluorescence in retinitis pigmentosa. Retina. 2011;31(8):1670-1679. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318206d155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lima LH, Burke T, Greenstein VC, et al. . Progressive constriction of the hyperautofluorescent ring in retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(4):718-727, 727.e1-727.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cabral T, Sengillo JD, Duong JK, et al. . Retrospective analysis of structural disease progression in retinitis pigmentosa utilizing multimodal imaging. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):10347. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10473-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kellner U, Kellner S, Weber BH, Fiebig B, Weinitz S, Ruether K. Lipofuscin- and melanin-related fundus autofluorescence visualize different retinal pigment epithelial alterations in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Eye (Lond). 2009;23(6):1349-1359. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Legras R, Gaudric A, Woog K. Distribution of cone density, spacing and arrangement in adult healthy retinas with adaptive optics flood illumination. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0191141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sawides L, de Castro A, Burns SA. The organization of the cone photoreceptor mosaic measured in the living human retina. Vision Res. 2017;132:34-44. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2016.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Triolo G, Pierro L, Parodi MB, et al. . Spectral domain optical coherence tomography findings in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmic Res. 2013;50(3):160-164. doi: 10.1159/000351681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fahim AT, Daiger SP, Weleber RG. Nonsyndromic retinitis pigmentosa overview In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al. , eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Study Details

eFigure 1. Conservation of Novel Missense Mutated Amino Acids or Splicing Sites for PDE6A and PDE6B Genes

eFigure 2. Fundus Color, Short-Wavelength (SWAF) and Near-Infrared (NIRAF) Autofluorescence and SD-OCT Horizontal Cross-Section Photos of Patients Harboring Mutations in PDE6A And PDE6B at Different Ages

eFigure 3. Kaplan-Meier Analyses of BCVA of PDE6A- and PDE6B-Mutated Patients

eFigure 4. Serial Measurements of BCVA and VF With Parallel SD-OCT, SWAF and NIRAF Images for CIC04774- PDE6A and CIC05351-PDE6B Patients

eFigure 5. Measurements of Structural Changes

eFigure 6. Longitudinal Structural Changes of SD-OCT, SWAF and NIRAF Images of PDE6A- and PDE6B-Mutated Patients

eTable 1. Patients With PDE6A Mutations Identified in This Study With In Silico Analysis of the Variants

eTable 2. Patients With PDE6B Mutations Identified in this Study With In Silico Analysis on Variants

eTable 3. List of Mutations Identified in PDE6A in Our Cohort

eTable 4. List of Mutations Identified in PDE6B in Our Cohort

eTable 5. Clinical Data of Patients Harboring PDE6A Mutations

eTable 6. Clinical Data of Patients Harboring PDE6B Mutations

eTable 7. BCVA, VF and Imaging Data From Both Eyes of the Patients in Both Genetic Cohorts