Watch a video presentation of this article

Watch the interview with the author

The clinical presentation of primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) has changed significantly in recent decades, and now most patients are asymptomatic middle‐aged women with (1) abnormal liver chemistries, particularly mild elevations of alkaline phosphatase (AP), gamma‐glutamyltransferase (GGT), and aminotransferases, and (2) early histological stages of the disease.1, 2 These changes are associated with long‐term survival; consequently, the main goal of therapy is to improve cholestasis and thus prevent the progression of liver damage that eventually results in liver cirrhosis and reduced survival free of transplantation. Additionally, the slow progression of the disease limits the hard endpoints of death or liver transplantation for treatment efficacy; therefore, response to treatment is defined as improvement or lack of progression in biochemical markers, liver histology, or the consequences of portal hypertension.

Because of the presumed immunologic pathogenesis of the disease, a number of randomized and observational and pilot studies were performed in the 1980s assessing the effect of several agents, including azathioprine, chlorambucil, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, prednisone, and cyclosporine. Other agents have been evaluated as well, including penicillamine, colchicine, malotilate, thalidomide, silymarin, and atorvastatin. No clear or even deleterious consequences were derived from these studies.1, 2

Ursodeoxycholic Acid and Biochemical Criteria for Optimal Response

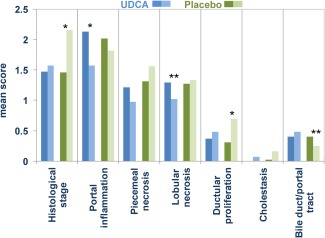

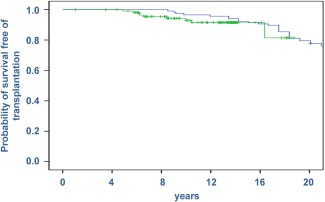

Over the past two decades, increasing evidence has indicated that ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) at 13‐15 mg/kg/day is the treatment of choice for patients with PBC based on placebo‐controlled trials and more recent long‐term case‐control studies. UDCA markedly decreases serum bilirubin, AP, GGT, cholesterol and immunoglobulin M (IgM) levels, and ameliorates histological features in patients with PBC. Moreover, long‐term treatment with UDCA delays the histological progression of the disease3 (Fig. 1), mainly in patients with early histological stage.1, 2 Despite these favorable effects, the use of UDCA in patients with PBC has been questioned, because no clear benefit in survival or time to liver transplantation have been demonstrated in different meta‐analyses and in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.4 However, it should be noted that in some trials, most patients were asymptomatic and at the initial stages of the disease. Therefore, UDCA should be given for much longer periods to confirm apparent changes on survival free of liver transplantation. More recently, a number of studies have shown that biochemical response to UDCA, as indicated by improvement of one or more biochemical tests, assessed at 1 year and 6 months clearly predict the long‐term outcome, since in UDCA responders the survival is similar to that estimated for the matched control population (Fig. 2). Several definitions of optimal biochemical response to UDCA have been proposed (Table 1),5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and ∼40% of patients fulfill at least one condition of incomplete biochemical response. These patients have an increased risk of progression events, and decreased survival free of transplantation. Therefore, the patients with suboptimal biochemical response to UDCA outline the group of patients in whom further single or combined treatments with UDCA are needed. Accordingly, data on the effect of fibrates alone or in combination with UDCA and budesonide in combination with UDCA have been reported. The effect of new agents have been reported, including obeticholic acid; however, this particular agent is not commercially available. Apart from these agents, antiretroviral treatments have been proposed, but the results are meager and the rationale based on the hypothesis of a possible retroviral etiology of PBC has not been validated.1, 2 Molecular therapies with antibodies against B cells and interleukins are currently being investigated.

Figure 1.

Differences in the histological analysis performed within an interval of 4.4 years in patients taking UDCA (blue bars) or placebo (green bars), before (dark blue/dark green) and after (light blue/light green) treatment. Portal inflammation and lobular necrosis decreased in patients taking UDCA, whereas the histological stage and the severity of ductular proliferation increased in patients under placebo. Bile duct paucity was also more prominent in the last biopsy in patients with placebo.3 *P < 0.001. **P < 0.01

Figure 2.

Survival free of liver transplantation in PBC patients with the Barcelona criteria for optimal response. The extended analysis after 5 years of the criteria definition shows that the probability of survival in these patients (green line) parallels that expected of the standardized population (blue line).

Fibrates

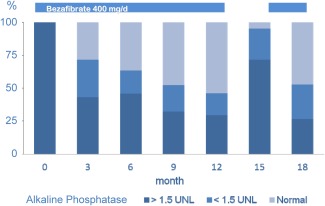

Early studies from Japan described an improvement of biochemical cholestasis and liver histology when giving fibrates (bezafibrate or fenofibrate) in patients with PBC. More recently, treatment with fibrates in PBC has been evaluated in Western countries with similar results regarding to the improvement of cholestasis and cytolysis12, 13, 14, 15 (Table 2). Adding fenofibrate (160 mg/day) for 1 year in 20 patients without biochemical optimal response to UDCA, as defined by the Barcelona criteria, resulted in a significant decrease in cholestasis and cytolysis and other markers of inflammation, such as interleukin‐1 and interleukin‐6.13 These data are consistent with the study performed in our center, which has evaluated 30 patients with PBC without biochemical response to UDCA or with AP levels 1.5 times the upper limit of normal. The addition of bezafibrate (400 mg/day) to UDCA has favorable effects; this combined treatment results in normalization or a dramatic decrease of markers of cholestasis (Fig. 3) and cytolysis after 1 year, as well as a noticeable decrease of itching.14 Discontinuation of bezafibrate for 3 months was associated with a significant elevation of biochemical markers and development of itching. These favorable consequences were more relevant in patients with lower severity and early disease as measured by transient elastography. No severe adverse effects resulting from combined treatment with fibrates have been described, but some patients have experienced heartburn or nausea, resulting in treatment discontinuation. The anticholestatic mechanisms of fibrates are not completely elucidated, but the main action may result from being perixosome proliferator‐activated receptor agonists with multiple targets regulating bile‐transporter expression and inflammation.15 Moreover, fibrates up regulate the expression of multiple drug resistance gene‐3.

Table 2.

Summary of Studies Assessing the Effect of Fibrates in Patients with PBC11

| Study | Country | Year | Daily Dose | Daily Dose UDCA | No. of Patients | Duration | Outcomes Improvement | Adverse Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bezafibrate | ||||||||

| Nakai22 | Japan | 2000 | 400 mg | 600 mg | 10 | 12 mo | AP, ALT, GGT, IgM | No |

| Kurihara23 | Japan | 2000 | 400 mg | 12 | 12 mo | AP, ALT, GGT, IgM | No | |

| Kanda24 | Japan | 2002 | 400 mg | 600 mg | 11 | 6 mo | AP | No |

| Akbar25 | Japan | 2005 | 400 mg | 600 mg | 10 | 12 mo | AP, ALT, GGT, IgM, Chol | No |

| Kita26 | Japan | 2006 | 400 mg | 600 mg | 22 | 6 mo | AP, GGT | No |

| Hazzan27 | Israel | 2010 | 400 mg | 900‐1500 mg | 8 | 4‐12 mo | AP, GGT | No |

| Lens14 | Spain | 2014 | 400 mg | 13‐15 mg/kg | 30 | 12 mo | AP, GGT, ALT, Chol, TGR | Heartburn |

| Honda15 | Japan | 2013 | 400 mg | 600 mg | 19 | 3 mo | AP, GGT, ALT, Chol, TGR, IgM | No |

| Fenofibrate | ||||||||

| Ohira28 | Japan | 2002 | 150‐200 mg | 600‐900 mg | 7 | 6 mo | AP, GGT, IgM | No |

| Walker29 | UK | 2009 | 134‐200 mg | 16 | 3‐4 mo | AP, IgM | No | |

| Liberopoulos30 | Greece | 2010 | 200 mg | 600 mg | 6 | 2 mo | AP, GGT | No |

| Levy13 | USA | 2010 | 160 mg | 13‐15 mg/kg | 20 | 12 mo | AP, AST, IgM,IL‐1, IL‐6 | Esophagitis, ALT increase |

Abbreviations: AP, alkaline phosphatase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; Chol: cholesterol; GGT, gamma‐glutamyltransferase; IgM, immunoglobulin M; IL‐1: interleukin‐1; IL‐6: interleukin‐6; TGR, triglycerides.

Figure 3.

Adding bezafibrate (400 mg/day) to patients with PBC receiving UDCA (13‐15 mg/kg/day) resulted in marked improvement of cholestasis as indicated by the alkaline phosphatase levels, which normalized or were <1.5 times the upper limit of normal levels (UNL) in most cases (light blue) after 1 year of treatment.14

Table 1.

Biochemical Criteria of Optimal Response to UCDA in PBC

| Criteria | Evaluation Time | Biochemical Suboptimal Response to UDCA |

|---|---|---|

| Rochester5 | 6 months | AP >2 × ULN or Mayo score ≥4.5 |

| Barcelona6 | 1 year | AP >1 × ULN and decrease in AP ≤40% |

| Paris I7 | 1 year | AP ≥3 × ULN or AST ≥2 × ULN or bilirubin >1 mg/dL |

| Rotterdam8 | 1 year | Abnormal bilirubin and/or albumin levels |

| Toronto9 | 2 years | AP >1.67 × ULN |

| Paris II10 | 1 year | AP ≥1.5 × ULN or AST ≥1.5 × ULN or bilirubin >1 mg/dL |

| Beijing11 | 6 months | AP >3 ULN, increased bilirubin, decreased albumin levels |

Abbreviations: AP, alkaline phosphatase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ULN, upper limit of normal.

In summary, data from all of the aforementioned studies suggest that combined treatment with fibrates in patients without optimal biochemical response to UDCA could be useful, because it would improve the degree of cholestasis and may minimize the long‐term management of these patients; however, more studies are already needed. A phase 3 trial is ongoing in Europe to assess bezafibrate as an assisting therapy to UDCA (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01654731).

Budesonide

Budesonide is a nonhalogenated glucocorticoid absorbed in the small intestine with 90% first‐pass hepatic metabolism in healthy individuals and with glucocorticoid receptor‐binding activity higher than prednisolone. Two randomized trials showed that the combination of budesonide (6‐9 mg/day) with UDCA is more effective for improving liver biochemistries and histology than UDCA alone in patients with PBC who do not have cirrhosis.16, 17 In a recent 3‐year prospective, randomized study of 77 patients, serum liver enzymes decreased significantly in both treatment arms, but histological stage and fibrosis improved in the combined treatment group and deteriorated in the UDCA group.16 The same positive effect of combination therapy on liver histology (stage, fibrosis, and inflammation) and laboratory values was observed by Leuschner et al.,17 but with a higher dose of budesonide (9 mg/day) during 2 years of therapy. Angulo et al.18 reported minimal further benefits to UDCA after adding budesonide (9 mg/day) for 1 year in a pilot study of 22 PBC patients who had shown an incomplete response to UDCA. Mild glucocorticoid‐related side effects were associated with budesonide treatment.

Although these results are remarkable, the effect of combined treatment with budesonide should be established in a large randomized trial that is currently being evaluated in Europe (EudraCT Number: 2007‐004040‐70). Meanwhile, this treatment can be assayed in patients without optimal UDCA biochemical response, and probably in patients with higher indices of inflammation.

Obeticholic Acid

Obeticholic acid (6‐alpha‐ethyl‐chenodeoxycholic acid) is an innovative synthetic derivative of chenodeoxycholic acid, being 100 times more potent as a farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonist. The FXR is expressed in the liver, intestine, adrenal glands, and kidneys and plays an important role in the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids. Among other functions, including the regulation of key aspects of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, FXR reduces bile acid synthesis acting on the enzyme cholesterol 7α hydroxylase and also by down‐regulating the expression of the sodium/taurocholate cotransporting peptide, a bile acid uptake protein. In addition, FXR activation increases expression of the bilirubin and phospholipid (multiple drug resistance gene‐3) export pumps and FXR also stimulate intestinal factors such as fibroblast growth factor 19, which provide a negative feedback loop from the intestine to hepatocytes, contributing to repression of bile acid synthesis.19 In a phase 2 efficacy and safety assessment in PBC patients, addition of obeticholic acid in patients with stable UDCA dosage and with increased AP levels resulted in an ∼25% reduction of AP compared with placebo, with a parallel decrease of aminotransferase, GGT, and IgM levels, as well as one surrogate marker of bile acid synthesis. These effects were associated with a high incidence of pruritus with a dose‐response relationship, leading to drug discontinuation in some patients.20 A long‐term phase 3 trial of obeticholic acid in UDCA‐treated patients based on an up‐titration assessment of this new agent is currently ongoing (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01473524).

Obeticholic acid alone in patients with PBC resulted in a favorable biochemical effect in another trial with 50% reduction in AP levels.21 Again, aminotransferase, GGT, and IgM levels decreased significantly with obeticholic acid, although pruritus probably resulted from the high dosage of this agent. A 12‐month extension trial showed a sustained biochemical response (EudraCT Number: 2011‐004728‐36).

Conclusion

Approximately 40% of PBC patients receiving standard doses of UDCA (13‐15 mg/kg/day) had a suboptimal response, defined by different plain biochemical tests. These criteria characterize the group of patients requiring further treatments. The information available has been insufficient thus far, but the favorable effects of adding fibrates and budesonide to UDCA are encouraging and represent something to offer patients who do not have an optimal response. A new agent, obeticholic acid, is under evaluation with clear favorable biochemical effects on cholestasis and inflammatory response; in addition, molecular therapies with antibodies against B cells and interleukins are currently being investigated. At present, a practical recommendation in patients with suboptimal response to UDCA will be adding fibrates or budesonide according to the stage of the disease and the indices of inflammation. Addition of obeticholic acid will depend on the results of the ongoing trial, and it is important to note that the long‐term beneficial effects of adding these agents are linked to the results of appropriate placebo‐controlled trials.

Abbreviations

- AP

alkaline phosphatase

- FXR

farnesoid X receptor

- GGT

gamma‐glutamyltransferase

- IgM

immunoglobulin M

- PBC

primary biliary cirrhosis

- UDCA

ursodeoxycholic acid.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1. European Association for the Study of the Liver . EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of cholestatic liver diseases. J Hepatol 2009;51:237‐267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lindor KD, Gershwin ME, Poupon R, Kaplan M, Bergasa NV, Heathcote EJ. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology 2009;50:291‐308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Parés A, Caballeria L, Rodés J, Bruguera M, Rodrigo L, García‐Plaza A, et al. Long‐term effects of ursodeoxycholic acid in primary biliary cirrhosis results of a double‐blind controlled muticentric trial. J Hepatol 2000;32:561‐566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rudic JS, Poropat G, Krstic MN, Bjelakovic G, Gluud C. Ursodeoxycholic acid for primary biliary cirrhosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:CD000551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jorgensen R, Angulo P, Dickson ER, Lindor KD. Results of long‐term ursodiol treatment for patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:2647‐2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Parés A, Caballeria L, Rodes J. Excellent long‐term survival in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis and biochemical response to ursodeoxycholic acid. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:715‐720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Corpechot C, Abenavoli L, Rabahi N, Chretien Y, Andreani T, Johanet C, et al. Biochemical response to ursodeoxycholic acid and long‐term prognosis in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology 2008;48:871‐877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kuiper EM, Hansen BE, de Vries RA, den Ouden‐Muller JW, van Ditzhuijsen TJ, Haagsma EB, et al. Improved prognosis of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis that have a biochemical response to ursodeoxycholic acid. Gastroenterology 2009;136:1281‐1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kumagi T, Guindi M, Fischer SE, Arenovich T, Abdalian R, Coltescu C, et al. Baseline ductopenia and treatment response predict long‐term histological progression in primary biliary cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:2186‐2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Corpechot C, C hazouillères O, Poupon R. Early primary biliary cirrhosis: biochemical response to treatment and prediction of long‐ term outcome. J Hepatol 2011;55:1361‐1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang LN, Shi TY, Shi XH, Wang L, Yang YJ, Liu B, et al.. Early biochemical response to ursodeoxycholic acid and long‐term prognosis of primary biliary cirrhosis: results of a 14‐year cohort study. Hepatology 2013;58:264‐272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lens S, Parés A. Fibrates in the treatment of primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterologia y Hepatologia Continuada 2011;10:280‐283. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Levy C, Peter JA, Nelson DR, Keach J, Petz J, Cabrera R, et al. Pilot study: fenofibrate for patients with primary biliary cirrhosis and an incomplete response to ursodeoxycholic acid. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;33:235‐242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lens S, Leoz M, Nazal L, Bruguera M, Parés A. Bezafibrate normalizes alkaline phosphatase in primary biliary cirrhosis patients with incomplete response to ursodeoxycholic acid. Liver Int 2014;34:197‐203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Honda A, Ikegami T, Nakamuta M, Miyazaki T, Iwamoto J, Hirayama T, et al. Anticholestatic effects of bezafibrate in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis treated with ursodeoxycholic acid. Hepatology 2013;57:1931‐1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rautiainen H, Kärkkäinen P, Karvonen AL, Nurmi H, Pikkarainen P, Nuutinen H, et al. Budesonide combined with UDCA to improve liver histology in primary biliary cirrhosis: a three‐year randomized trial. Hepatology 2005;41:747‐752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leuschner M, Maier KP, Schlichting J, Strahl S, Herrmann G, Dahm HH, et al. Oral budesonide and ursodeoxycholic acid for treatment of primary biliary cirrhosis: results of a prospective double‐blind trial. Gastroenterology 1999; 117:918‐925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Angulo P, Jorgensen RA, Keach JC, Dickson ER, Smith C, Lindor KD. Oral budesonide in the treatment of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis with a suboptimal response to ursodeoxycholic acid. Hepatology 2000;31;318‐323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Trauner M, Halilbasic E. Nuclear receptors as a new perspective for the management of liver diseases. Gastroenterology 2011;140:1120‐1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mason A, Luketic VA, Lindor KD, Hirschfield G, Gordon SC, Mayo ML, et al. Farnesoid‐X receptor agonists: a new class of drugs for the treatment of PBC? An international study evaluating the addition of obeticholic acid (int‐747) to ursodeoxycholic acid (Abstract). Hepatology 2010;52:375A. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kowdley KV, Jones D, Luketic V, Chapman R, Burroughs A, Hirschfield G, et al. An international study evaluating the farnesoid X receptor agonist obeticholic acid as monotherapy in PBC (Abstract). J Hepatol 2011;54:S13. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nakai S, Masaki T, Kurokohchi K, Deguchi A, Nishioka M. Combination therapy of bezafibrate and ursodeoxycholic acid in primary biliary cirrhosis: a preliminary study. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:326‐327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kurihara T, Niimi A, Maeda A, Shigemoto M, Yamashita K. Bezafibrate in the treatment of primary biliary cirrhosis: comparison with ursodeoxycholic acid. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:2990‐2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kanda T, Yokosuka O, Imazeki F, Saisho H. Bezafibrate treatment: a new medical approach for PBC patients?. J Gastroenterol 2003;38:573‐578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Akbar SM, Furukawa S, Nakanishi S, Abe M, Horiike N, Onji M. Therapeutic efficacy of decreased nitrite production by bezafibrate in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol 2005;40:157‐163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kita R, Takamatsu S, Kimura T, Kokuryu H, Osaki Y, Tomono N. Bezafibrate may attenuate biliary damage associated with chronic liver diseases accompanied by high serum biliary enzyme levels. J Gastroenterol 2006;41:686‐692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hazzan R, Tur‐Kaspa R. Bezafibrate treatment of primary biliary cirrhosis following incomplete response to ursodeoxycholic acid. J Clin Gastroenterol 2010;44:371‐373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ohira H, Sato Y, Ueno T, Sata M. Fenofibrate treatment in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:2147‐2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Walker LJ, Newton J, Jones DE, Bassendine MF. Comment on biochemical response to ursodeoxycholic acid and long-term prognosis in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology 2009;49:337‐338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liberopoulos EN, Florentin M, Elisaf MS, Mikhailidis DP, Tsianos E. Fenofibrate in primary biliary cirrhosis: a pilot study. Open Cardiovasc Med J 2010;4:120‐126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]