Abstract

Background

Cancer is diagnosed and managed by multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) in the UK and worldwide, these teams meet regularly in MDT meetings (MDMs) to discuss individual patient treatment options. Rising cancer incidence and increasing case complexity have increased pressure on MDMs. Streamlining discussions has been suggested as a way to enhance efficiency and to ensure high-quality discussion of complex cases.

Methods

Secondary analysis of quantitative and qualitative data from a national survey of 1220 MDT members regarding their views about streamlining MDM discussions.

Results

The majority of participants agreed that streamlining discussions may be beneficial although variable interpretations of ‘streamlining’ were apparent. Agreement levels varied significantly by tumour type and occupational group. The main reason for opposing streamlining were concerns about the possible impact on the quality and safety of patient care. Participants suggested a range of alternative approaches for improving efficiency in MDMs in addition to the use of treatment protocols and pre-MDT meetings.

Conclusions

This work complements previous analyses in supporting the development of tumour-specific guidance for streamlining MDM discussions considering a range of approaches. The information provided about the variation in opinions between MDT for different tumour types will inform the development of these guidelines. The evidence for variation in opinions between those in different occupational groups and the reasons underlying these opinions will facilitate their implementation. The impact of any changes in MDM practices on the quality and safety of patient care requires evaluation.

Keywords: cancer, streamlining, teamwork, effectiveness, multidisciplinary

Background

Multidisciplinary teams (MDTs), also described as multidisciplinary case/cancer conferences or tumour boards, are viewed as the ‘gold standard’ for the management of cancer patients in the UK.1 They were introduced in the 1990s to improve the quality of cancer care and survival rates. These teams meet weekly in MDT meetings (MDMs) to discuss and agree on treatment recommendations for individual patients. They also have a governance role to ensure the quality and safety of care by overseeing and monitoring the impact of treatment decisions made by individual clinicians.2 It is currently mandatory for all new or suspect cancer cases in the UK to be discussed at an MDM. The concept of MDT-driven care is also recognised internationally and embedded into healthcare systems around the world.3 4

MDTs and MDMs are highly valued by MDT members,5 recent systematic reviews have confirmed their positive impact on the decision-making process and treatment recommendations, although evidence for their impact on clinical outcomes is less strong.6 7 However, there is a need to enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of MDMs. Although the introduction of MDTs in the UK has been associated with improvements in quality of care, cancer is still the leading cause of death, cancer survival rates are lower than those in comparable countries8 and there is evidence for variation in effectiveness between MDTs.1 9 Increases in the cancer incidence without a comparable increases in the healthcare workforce, coupled with a growing number of available treatment options, has increased both the number of patients discussed and the complexity of decision-making meaning that high-quality discussions of complex cases are essential.5 The need to identify methods to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of MDTs (and MDMs) is not restricted to the UK, similar issues have been identified and are being investigated in other countries.10–13

It has been suggested that selective review of cases and streamlining discussions to prioritise more complex cases could improve the effectiveness and efficiency of MDMs.1 3 14 Observational studies suggest that the average length of patient discussions is between 2 and 3 min.5 15 Time pressure and excessive case-loads have consistently been identified as impacting on the quality of decision-making in MDMs.5 14 16

Initial analyses of the data collected in a recent survey of MDT members commissioned by the Cancer Research UK (CRUK) suggested support from MDT members for streamlining discussions. Variation in the level of agreement between MDTs for different tumour types was identified but no systematic, statistical analysis of the data was reported.5 This paper aims to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of MDT members’ opinions about streamlining, including variation in views by tumour type and occupational group, and the underlying reasons for these opinions. The results of these analyses will inform ongoing discussions about whether streamlining discussions in MDM for different tumour types could contribute to enhancing the effectiveness of MDM for different tumour types, and if so, which approaches could be used.

Materials and methods

The 2017 CRUK survey

In 2017, CRUK commissioned two surveys of MDT members.5 The first aimed to identify key issues facing MDTs, and the second was designed to gain consensus and obtain input to emerging recommendations about how to enhance the effectiveness of MDMs.

This study uses data from the second survey that obtained participants’ opinions regarding their support for a range of recommendations, including the streamlining of discussions in MDMs. The survey collected background information (professional group, role within the MDT, and region of the country). Information was also obtained about the tumour type discussed (if respondents attended multiple MDMs, they were asked to provide opinions about one) and the ‘type’ of MDT based on the geographical area served (local, regional/specialist, or super-regional). Patients were not involved in this secondary analysis.

Respondents were then asked to indicate their level of agreement with a series of statements using five-point Likert scales (from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree), and were able to add free-text comments. Questions were included about a range of possible recommendations for improving the effectiveness of MDM, including attendance requirements, streamlining discussions, the availability of patient information and non-case discussion benefits. This paper is focused on analysis of the 12 Likert statements regarding streamlining of discussions (table 1), and three free-text questions asking for ‘further comments on streamlining MDT discussions’.

Table 1.

Participants’ opinions about the usefulness, approaches used and governance of streamlining

| Disagree or strongly disagree | Neither agree or disagree | Agree or strongly agree | Missing | Kruskal-Wallis statistic | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n | Tumour type | Occupation group | MDT type | |

| Usefulness of streamlining | |||||||

| This approach of streamlining patient discussions could allow more straightforward cases to be progressed more quickly, rather than waiting for the weekly meeting | 190 (15.8) | 179 (14.9) | 831 (69.3) | 20 | 67.3 (<0.001) |

37.4 (<0.001) |

6.3 (0.042) |

| The MDT I selected above would benefit from some form of streamlining | 313 (25.8) | 183 (15.1) | 718 (58.9) | 6 | 48.2 (<0.001) |

43.5 (<0.001) |

4.8 (0.091) |

| Approaches for streamlining | |||||||

| For the MDT selected above, some patients should be discussed by a smaller team, rather than requiring discussion by the full MDT | 422 (34.7) | 119 (9.8) | 675 (55.5) | 4 | 82.1 (<0.001) |

57.0 (<0.001) |

2.9 (0.253) |

| For the MDT selected above, some patients should be placed on protocolised treatment pathways and are not needed to be discussed at the meeting at all | 498 (41.2) | 168 (13.9) | 542 (44.9) | 12 | 115.6 (<0.001) |

42.1 (<0.001) |

5.1 (0.078) |

| The streamlining of patient discussions should be performed in advance of the main MDT meeting to decide which patients should be discussed at the meeting, and which should receive a protocolised treatment plan | 271 (22.6) | 173 (14.5) | 753 (62.9) | 23 | 68.8 (<0.001) |

49.5 (<0.001) |

1.5 (0.482) |

| The clinician referring the patient to the MDT should be able to bypass the pre-MDT and refer straight to the full MDT | 175 (17.0) | 117 (11.4) | 737 (71.6) | 191 | 38.4 (<0.001) |

23.5 (<0.001) |

4.3 (0.118) |

| The clinician should be able to make treatment recommendations directly for newly diagnosed patients, without referring to either the full MDT or pre-MDT | 547 (53.2) | 163 (15.9) | 318 (30.9) | 192 | 74.1 (<0.001) |

36.3 (<0.001) |

0.7 (0.714) |

| Governance | |||||||

| If patients followed treatment protocols or had recommendations made by a smaller team, the full MDT reviewing a selection of these patients would provide sufficient governance of this process | 255 (21.3) | 244 (20.4) | 700 (58.4) | 21 | 71.1 (<0.001) |

37.1 (<0.001) |

5.8 (0.056) |

| Patient cases that are placed on a protocolised pathway should be made available to audit by the MDT | 24 (2.3) | 79 (7.7) | 924 (90.0) | 193 | 18.7 (0.096) |

78.3 (<0.001) |

7.3 (0.026) |

| The treatment protocols followed by the pre-MDT should be designed by a national body | 246 (24.1) | 379 (37.2) | 395 (38.7) | 200 | 4.9 (0.963) |

26.4 (0.002) |

9.3 (0.009) |

| The treatment protocols followed by the pre-MDT should be designed at a local level, based on recommendations made at a national level | 174 (17.0) | 293 (28.6) | 557 (54.4) | 196 | 25.9 (0.011) |

15.6 (0.075) |

0.2 (0.905) |

| The treatment protocols followed by the pre-MDT should be designed at a network level, based on recommendations made at a national level | 124 (12.1) | 291 (28.4) | 610 (59.5) | 195 | 14.1 (0.295) |

19.8 (0.019) |

3.9 (0.144) |

MDT, multidisciplinary team.

Streamlining was initially defined in the survey as developing processes so that ‘specialist time is focused on those cancer cases that don’t follow well-established clinical pathways, with other patients being discussed more briefly’. However, the majority of the Likert statements focused on approaches in which ‘some patients would be discussed at the meeting, and others would receive treatment recommendations from a different forum’. The statements suggested that patients not discussed at the full MDT could either be discussed in a smaller team, or that some patients could be placed on protocolised treatment pathways without discussion at the MDM. It was proposed that a smaller pre-MDM, attended by selected members of the full MDM, could ‘act to make recommendations for patients deemed straightforward’, which would ‘allow more complex patients to benefit from a longer discussion’.

The survey was disseminated to MDT members in the UK with the assistance of various professional bodies and completed online between March and May 2017. Further information about the survey content and methods has been published previously.5

Participants

The survey was completed by 1269 MDT members. A total of 49 respondents were excluded from the analysis; 2 were not from the UK, 35 were members of MDT for tumour types for which less than 15 responses were obtained and the remaining 12 did not complete all of the background information (table 2).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | All survey participants | Participants who made free-text comments | ||

| N | % | n | % | |

| Tumour type | ||||

| Breast | 177 | 14.0 | 53 | 15.2 |

| Colorectal | 134 | 10.6 | 48 | 13.8 |

| Lung | 141 | 11.1 | 41 | 11.8 |

| Urology | 162 | 12.8 | 31 | 8.9 |

| Gynaecology | 89 | 7.0 | 28 | 8.0 |

| Haematology | 77 | 6.1 | 18 | 5.2 |

| Head and neck | 130 | 10.3 | 26 | 7.5 |

| Skin | 101 | 8.0 | 35 | 10.1 |

| Upper GI | 97 | 7.7 | 22 | 6.3 |

| Brain | 44 | 3.5 | 11 | 3.2 |

| Child and young people | 33 | 2.6 | 7 | 2.0 |

| Cancer of unknown primary | 19 | 1.5 | 9 | 2.6 |

| Palliative care | 27 | 2.1 | 10 | 2.9 |

| Other* | 35 | 2.8 | 9 | 2.6 |

| Missing | 3 | – | 1 | – |

| Occupational group | ||||

| Chair or leader† | 179 | 14.2 | 68 | 19.5 |

| Coordinator or administrator | 120 | 9.5 | 25 | 7.2 |

| Oncologist | 141 | 11.2 | 43 | 12.4 |

| Surgeon | 167 | 13.2 | 46 | 13.2 |

| Radiologist | 107 | 8.5 | 30 | 8.6 |

| Pathologist | 78 | 6.2 | 24 | 6.9 |

| Other medical‡ | 101 | 8.0 | 29 | 8.3 |

| Clinical nurse specialist | 258 | 20.4 | 66 | 19.0 |

| Other nursing | 48 | 3.8 | 9 | 2.6 |

| Allied health professional | 64 | 5.1 | 8 | 2.3 |

| Missing | 6 | – | 1 | – |

| Region | ||||

| Wales | 154 | 12.2 | 45 | 12.9 |

| Scotland | 21 | 1.7 | 4 | 1.1 |

| Northern Ireland | 68 | 5.4 | 16 | 4.6 |

| North | 367 | 29.0 | 107 | 30.7 |

| Midlands and East | 186 | 14.7 | 52 | 14.9 |

| South West | 145 | 11.5 | 48 | 13.8 |

| South East | 147 | 11.6 | 41 | 11.7 |

| London | 176 | 13.9 | 35 | 10.0 |

| Ireland | 2 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Missing | 3 | – | 0 | – |

| MDT type | ||||

| Local | 681 | 54.0 | 187 | 54.0 |

| Regional/specialist | 522 | 41.4 | 142 | 41.0 |

| Super-regional | 58 | 4.6 | 17 | 4.9 |

| Missing | 8 | – | 3 | – |

*Other MDT types=Sarcoma (13), other (12), ocular (4), endocrine (3) and neuroendocrine (3).

†Chair or leader professions=Surgeon (75), oncologist (31), other medical (42), haematologist (9), CNS (4), dermatologist (4), respiratory (3), radiologist (3), other nurse (2), palliative care (1), allied health (1) and other (1).

‡Other medical=Other medical (77), haematologist (15), dermatologist (5), palliative care (3) and respiratory (1).

CNS, clinical nurse specialist; GI, gastrointestinal; MDT, multidisciplinary team.

Data cleaning

Frequencies and cross-tabulations were examined to explore and ensure the validity of the data and some variables were re-coded. The participant’s role within the MDT was combined with their professional group to create occupational groups, and locations were re-coded into National Health Service (NHS) regions (table 2). The agreement indicated by Likert statements was grouped to indicate whether respondents agreed, disagreed or had no opinion about each statement.

Quantitative analysis

The percentage of respondents who agreed, disagreed or had no opinion about each of the 12 statements relating to streamlining was examined. Evidence for variation in agreement between MDT for different tumour types, different ‘types’ of MDT and between members of different occupational groups was investigated using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test on the data including the original five categories of agreement. Where significant differences between groups were identified using a critical p value of 0.001 to allow for multiple testing; the level of agreement in different groups was examined graphically. All analyses were performed using SPSS V.24.017.

Qualitative analysis

The analysis of responses to the free-text questions commenced with an inductive process of reading and identifying common themes. Three team members (MZ, CT and LH) familiarised themselves with the data and independently proposed data-driven coding frameworks to identify participants views about the usefulness of, and approaches for, streamlining MDM discussions. These were discussed and a final coding framework agreed. Data were then coded against this framework by one of the researchers (MZ) and direct quotations were extracted to illustrate each of the themes.

Results

Characteristics of participants

Responses from 1220 MDT members were included in the analysis, including members of MDTs for all the major tumour sites, from local and regional MDTs, and from a range of professional groups throughout the UK (table 2). Of these, 349 (28.6%) provided answers in response to at least one of the free-text questions about streamlining. Those providing free-text comments were a representative sample of those from different occupational groups and MDTs for different tumours and different ‘types’ (table 2), and of those who agreed or disagreed with the quantitative statements about streamlining.

Support for streamlining

Although the majority of participants (69.3%) agreed that streamlining discussions could allow more straightforward cases to be progressed more quickly, and over half (58.9%) thought that some form of streamlining would be beneficial for their MDT, 25% did not think that streamlining would benefit their MDT (table 1). Most of the comments providing reasons for supporting or opposing streamlining were about the impact of not discussing all patients on the quality and safety of their care. Many participants who were opposed to streamlining felt that it was important that all patients were treated equally and had an opportunity for their case to be discussed at the MDM. In contrast, the most common reason given by those who supported streamlining was that straightforward cases did not require discussion. Others supported streamlining as a way of reducing the time that clinicians spent in MDMs (table 3).

Table 3.

Participants’ comments illustrating the reasons for supporting or opposing streamlining and the approaches for streamlining proposed in the survey

| Category | Reason for support | Reason for opposition |

| Impact of streamlining on the quality and safety of patient care |

Straightforward cases do not require discussion giving more time for discussion of complex cases ‘Most urology cancer cases have straightforward management where the MDT discussion gives a very little added benefit and consumes time that should be spent on difficult cases…’. ‘The number of patients that are currently needing discussion is getting bigger, which means that the more complex cases don't get the full time needed. The above approach would be a suitable alternative’. Streamlining will speed up treatment ‘It will help patients progressing in diagnosis and treatment pathway more smoothly and quickly’. ‘Many patients follow a well-organised pathway. The MDT sometimes slows this!’ |

Every patient is unique and should be discussed to ensure individualised, holistic care ‘I feel all patients have the right to get benefit from specialist knowledge of all members of the team’. ‘MDM allows us to discuss other medical and non-medical reasons why standard treatment by need to be altered’. Straightforward cases cannot be identified prior to MDM discussions ‘There's an underlying risk of wrongly categorising “simple” and “complex” pts at the beginning of the process … ending up with delays, wrong paths, wrong decision-making…’. MDM prevents errors ‘Some big mistakes can come from small errors, such as mislabelling or report being typed on the wrong patient, and the MDT is a good safeguard for this’. All cases need review by MDM to ensure safety ‘Wider team should see the minutes of those streamed in case they wish a wider review … Plus this should be audited to make sure that it fit for purpose using criteria laid down nationally’. Streamlining will delay treatment ‘I feel the above model adds complexity and uncertainty to the pathway that will lead to delays to patient treatment that are not present with a single full weekly MDT model’. |

| Impact of streamlining on time taken by clinicians time |

Will save clinician time ‘Streamlining is vital, MDTs are very expensive in terms of consultant time and many patients can be treated according to predefined protocols and do not require endless pointless discussions’. ‘I agree mainly because I sit in an MDT that takes 4 hours, is full of patients who the majority of us feel that don't get benefit from discussion … I am certain that you could save valuable (and expensive) time to direct more time to cases that require it and ensure the decisions made at the end of an MDT remain robust (difficult sometimes after 4 hours!!)’. |

Will take more clinician time, insufficient time available ‘All good ideas but to do this time needs to be taken to do it—we already spend a whole session on MDMs and we cannot afford more time off from clinical work’. ‘Where would we as radiologist find the time for a streamlining MDT meeting. I doubt our clinical managers would not allow us time in our job plan for this. It is difficult for even core members of the MDTs to be allowed to go to the MDT every week’. We have sufficient time already ‘We have no need of this in our centre. All our cases are discussed at MDT’. |

| Impact of streamling on clinician skills |

De-skilling of clinicians ‘Far too many routine decisions made at MDTs. We are intelligent highly trained professionals but now have been trained to be unable to make a decision’. |

Educational role of MDT ‘MDTs are opportunities for learning for junior members of the team’. |

| Governance issues |

MDT should have autonomy ‘Local MDT should be able to decide level and length of discussion pertinent and relevant to each individual case’. Impact should be evaluated ‘Get evidence of efficacy before rolling this out’. |

|

| Use protocols or initiate treatment prior to MDM in order to streamline discussions |

Use protocols for straightforward cases ‘Most of the cases are treated through well set and known protocols, no need to discuss in an MDT, which is used by some to show authority and used for hidden agendas’. Initiate treatment prior to MDM ‘In haematology, this essentially happens already as the many patients commence treatment prior to the MDT and in fact would benefit from discussion much later when all prognostic results are available’. |

Protocols prevent individualised care ‘Every patient is unique and the issue with having a protocoled pathway is that this may not necessarily meet with the needs of the patient’. ‘I disagree with protocolised treatment without discussion, as this does not reflect the holistic care that all patients should receive’. |

| Pre-MDT meeting to select cases for streamlined discussions |

Pre-MDT meetings could contribute ‘This streamlining is done for MSCC patients, where a smaller meeting is done during the week and is listed on the main MDT for documentation purposes’. |

Pre-MDT will take more time ‘Initiating a pre-MDT will cause problems with job planning for already busy clinicians’. Increased process complexity could lead to errors ‘Another meeting would simply add more complexity, a greater chance for patients to get lost in an already creaking system that is barely coping with care delivery?’ |

| Clinicians to make independent decisions about treatment |

Clinicians should make decisions for routine cases ‘Let's just return to relying on clinicians' specialist training and judgement for routine cases’. |

Individual clinician decisions may compromise patient safety ‘This is potentially a dangerous backward step. The main function of the MDT is to prevent maverick clinicians treating patients without approval of the MDT…’. |

MDM, MDT meeting; MDT, multidisciplinary team; MSCC, metastatic spinal cord compression; pts, patients.

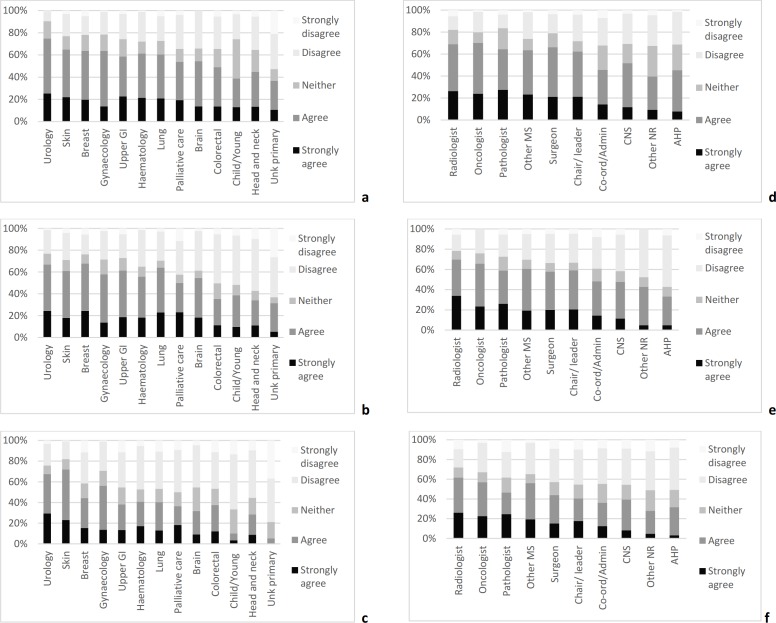

There were significant differences in levels of agreement with streamlining between members of MDTs for different tumour types. Agreement levels were consistently higher in MDTs for skin and urology patients and lower in colorectal, head and neck, children and young people, and cancers of unknown primary MDT (figure 1). This variation was supported by the free-text comments, no members of MDTs for tumour types that had the lowest levels of agreement with streamlining (unknown primary, head and neck, and children and young people) suggested that straightforward cases did not need to be discussed. All of the comments suggesting that cases in their MDT were too complex to allow streamlining were from members of MDTs in which there was a low level of agreement with streamlining, the majority were from members of MDTs for head and neck tumours or cancers of unknown primary. Levels of agreement with streamlining were also higher in doctors, particularly oncologists, radiologists and pathologists, and lower in coordinators, nurses and allied health professionals (figure 1). There was a very little variation in opinions about streamlining between members of MDTs at the regional and local levels (table 1).

Figure 1.

Variation in opinions about the benefits and methods used for streamlining between MDT for different types of tumour and occupational groups. (A) Agreement that the selected MDT would benefit from some form of streamlining in MDT for different tumour types. (B) Agreement that some patients in the selected MDT should be discussed by a smaller team, rather than by the full MDT in MDT for different tumour types. (C) Agreement that some patients in the selected MDT should be placed on protocolised treatment pathways and not discussed at the meeting in MDT for different tumour types. (D) Agreement that the selected MDT would benefit from some form of streamlining in different occupational groups. (E) Agreement that some patients in the selected MDT should be discussed by a smaller team, rather than by the full MDT in different occupational groups. (F) Agreement that some patients in the selected MDT should be placed on protocolised treatment pathways and not discussed at the meeting in different occupational groups. AHP, allied health professional; Child/Young, children and young people; CNS, clinical nurse specialist; Co-ord/Admin, Co-ordinator/administrator; GI, gastrointestinal; MDT, multidisciplinary team; other MS, other medical speciality; other NR, other nursing role; Unk, unknown.

Streamlining approaches

There was less agreement with the specific approaches proposed in the survey than with the idea that streamlining may be beneficial (table 1). Participants’ comments about the benefits and problems associated with the proposed approaches for streamlining were again predominantly focused on the quality and safety of care and clinicians time commitments. It was suggested that protocols may prevent individualised treatment, and that introducing additional meetings would increase the complexity of MDM processes and could lead to errors. Participants were also concerned about whether clinicians would have sufficient time available to attend additional meetings. A small number of participants suggested that discussions to decide which patients to streamline could be ‘virtual, done by e-mail’ to reduce the time spent in meetings.

There was little support (30.9%) for the idea that clinicians should be able to make treatment recommendations for newly diagnosed patients without referring to the MDT (table 1), the safety implications of allowing clinicians to make treatment decisions without MDT approval was highlighted (table 3).

Levels of agreement with these proposed approaches varied considerably between MDTs for different tumour types; for example, agreement with the use of protocolised treatment pathways ranged from 5.3% of members of MDTs for cancers of unknown primary to 72.3% of members of MDT for skin (figure 1).

Almost all participants, in MDT for all tumour types, agreed that patients placed on a protocolised pathway should be audited by the MDT. Most participants supported the development of protocols at the local or network level, only 9.7% of participants agreed that protocols should be developed at national level without also agreeing with development at the local or network level based on recommendations made at national level (table 1).

In addition to comments about the approaches for streamlining proposed in the survey, participants suggested a range of alternative approaches to improve the effectiveness of MDMs (table 4).

Table 4.

The alternative approaches for streamlining suggested by participants

| Prioritisation of agenda to spend more time on complex cases | ‘We already have an A list B list system whereby non-complex cases can be nodded through without formal discussion unless a member wishes to discuss the case’. |

| Grouping of cases by professionals required | ‘We already streamline the melanoma meeting: radiology first, then the radiologist and clinical oncologist leave’. |

| Separate MDM for different tumour groups or purpose of discussion | ‘Benign patients could be discussed by radiologist, pathologist and surgeon Aline without the whole team. We would also get benefit from a separate metastatic MDT’. ‘The MDT is for management decisions. Pre- or non-MDT could be for diagnostic decisions’. |

| Selection by the MDT chair | ‘I strongly feel that the MDT lead should vet ALL cases beforehand so as to verify if they are appropriate for discussion’. |

MDM, MDT meeting; MDT, multidisciplinary team.

The most common alternative suggestion for focussing discussions on more complex cases was prioritisation of such cases within the agenda, so that less time is spent discussing the more straightforward cases.

Other methods for improving the effectiveness of MDMs those did not focus discussion on complex cases were (i) grouping of cases so that different professionals attended only the sections of the MDM for which their input is required and (ii) having a separate MDM for different types of cases. Finally, a few participants suggested that other methods of improving the effectiveness of meetings were more important than streamlining. These included changing attendance rules to provide specialty cover rather than having individual attendance requirements, ensuring that participants had sufficient time to prepare so that all the required patient information was available prior to meetings, and improving chairing so that there is more effective management of discussions.

Importantly, the analysis of free-text comments also highlighted the lack of clarity among respondents about what ‘streamlining’ meant and how the proposed approaches might achieve this. Several participants suggested that they were already streamlining discussions by grouping cases according to the professionals required for saving clinicians’ time (table 4). However, this approach is not in line with the definition of streamlining, which aims to focus discussions on complex cases. In addition, several participants questioned what was meant by a pre-MDT, one asked ‘What exactly is a pre-MDT? Are you meaning a diagnostic MDT or new patient MDT?’ There were also a small number of participants who suggested that it was important to consider the needs of individual MDTs, for example, 'you really need to look at the needs of individual MDTs—not a one box fits all approach'.

Discussion

This comprehensive analysis of opinions about streamlining will inform ongoing discussions about how to improve the effectiveness of MDM. It confirmed that while MDT members generally supported streamlining MDM discussions, this may not be appropriate for all MDMs, and suggested that streamlining could be achieved using approaches other than those proposed in the survey. The systematic analysis of free-text responses provides a deeper insight into the acceptability and feasibility of the proposed strategies, which could facilitate their implementation.

Support for streamlining

The impact of streamlining MDM discussions on the quality and safety of patient care was the main factor influencing opinions about whether streamlining would be beneficial. Many participants opposed streamlining because they were concerned about the potential impact of not discussing all patients on the quality and safety of their care, particularly if treatment decisions were made by individual clinicians without referral to the MDT, which was the main reason for the introduction of MDTs in the 1990s.

On the other hand, some participants suggested that many cases did not benefit from MDM discussions and indeed waiting for MDM discussions may even delay treatment for some patients and also that discussing all cases at MDM meant that there was insufficient time allocated for the discussion of more complex cases. This perception that the quality of decisions may be limited by the time available is in line with previous findings, those suggested that treatment decisions were less likely towards the end of MDMs5 18 prompting calls for prioritisation of complex cases in urology MDM.3 Although focussing on complex cases may be a good idea in theory several participants felt that it was not possible to identify straightforward cases prior to discussion at the MDM.

Our analyses confirmed that variation in case complexity between MDT for different tumour types may be related to the level of agreement with streamlining. Members of MDTs for tumour types in which there was lower levels of agreement with streamlining were more likely to say that cases in their MDT were too complex to allow streamlining of discussions. However, this relationship between complexity and support for streamlining was not apparent in the analysis by ‘type’ of MDT, where agreement with streamlining was no stronger in the local MDT than in regional ones, where more complex cases are discussed.

The time taken by MDMs was another factor influencing opinions about the usefulness of streamlining, the need to save clinician time was an important factor driving support for streamlining. The variation in time spent in MDMs by different professionals may account for the variation in the level of support for streamlining between those in different occupational groups. Oncologists, radiologists and pathologists are more likely to attend multiple MDMs, and also to spend more time preparing for MDM.19 20 This may at least partially explain why they were more likely to agree with streamlining to reduce the number of cases discussed. Coordinators, nurses and allied health professionals were less supportive of streamlining, which may reflect their focus on facilitating a holistic approach to decision-making.16 Alternatively, it may be that they have a more risk-averse outlook leading to less support to remove some patients from MDM discussion.21 These differences between occupational groups—whatever their reason—supports previous recommendations that the differing perspectives of various MDT participants should be considered when implementing initiatives to improve MDTs.19 22 23

Although many participants suggested that streamlining discussions could reduce the time spent in MDMs, some suggested that introducing pre-MDT meetings could actually increase the time that clinicians spent in meetings, highlighting the need for alternative approaches to be considered.

There are clearly differing views about how streamlining MDM discussions might impact on the quality and safety of patient care and the ability of MDT to fulfil its governance role and variation between MDT for different tumour types. Although streamlining MDM discussion could contribute to saving clinician time and enhancing discussion quality in some MDM, further discussion and clarification about how the governance role of MDT should be maintained following the introduction of streamlining would be required. These discussions should include a consideration of how those making decisions about patient treatment will be kept updated about developments, such as personalised medicine and targeted cancer therapy.

Streamlining approaches

Concerns about patient safety may have prompted alternative suggestions for improving the efficiency of MDM without excluding cases from MDM discussions. Some participants suggested that they were streamlining discussions by ‘triaging’ cases before MDM meetings so that complex cases were prioritised for more in-depth discussion. This suggestion is consistent with the broad definition of streamlining used in the survey, which specifies that ‘specialist time is focused on those cancer cases that don’t follow well-established clinical pathways with other patients being discussed more briefly’,1 but not with the proposal to use protocolised pathways and exclude some patients from MDM discussions.

Participant’s descriptions of other approaches to improve the efficiency of meetings without focussing discussion on complex cases, by grouping cases according to the professionals required for discussions or having separate MDM, highlighted the confusion about what is meant by streamlining, and the need for caution in interpreting data on the level of support for streamlining. Previous studies have found support for grouping and prioritisation of cases but there was little support for separating MDT by subcategory of tumour in urology MDT.3 24 25 Other efficiency improving suggestions included enhancing the preparation for meetings, which could be achieved by review of pathology and radiology results and the use of standardised data sets for diagnostic information; reviewing attendance rules and ensuring effective chairing. These are in line with the recommendations from previous investigations, which also suggested that patients should be more involved in decision-making.14 26

Evaluation of changes in MDM practices

The need to obtain evidence about the impact of innovations in MDM practices on the quality and safety of care has been highlighted previously27 and was supported by survey participants. Such evidence would contribute significantly to resolving the issue of whether discussing the treatment plans for all patients is essential to ensure effective care.28 29 This would allow decisions about MDM practices to be made on the basis of equality of outcomes rather than equality of treatment. Assessing the effectiveness of MDTs is complicated by regulatory and ethical considerations,24 30 so evidence about the impact of MDTs on clinical outcomes and the cost-effectiveness of MDT care is unclear.6 7 31 Much of the evidence for the effectiveness of MDT is based on the assessment of the quality of decision-making and the development and implementation of treatment plans.3 15 22 32 Studies to evaluate the impact of improvements on the patient outcomes could also be considered. Given the complex nature of MDT processes, the likely variation required by tumour type as well as organisational context factors, a realist evaluation may be appropriate to identify how MDMs work, for which patients and in which contexts.33 This could allow identification of the mechanisms by which MDMs confer benefit to patients and staff, taking account of the contextual factors.30 In the meantime tools, such as MDT-FIT (MDT-Feedback for Improving Teamworking),34 35 can be used to empower MDT to assess and improve their functioning.

Strengths and limitations

This analysis has made a significant contribution to understanding the concerns underlying MDT members’ objections to streamlining MDM discussions. It has highlighted the extent of variation in opinions between MDT for different tumour types. The main strength of this study was that it made use of data from a large population, which provided a good representation of MDT members from different professional groups throughout the UK and those in MDTs for all of the most common tumour types. Another strength was the mixed methods approach taken to the analysis—integrating quantitative and qualitative data to obtain a deeper understanding of the underlying reasons for the variation in opinions about streamlining.

Limitations of this study include the possibility of non-response bias as participation in the survey was voluntary so those who completed it may hold different views from those who did not. There were also methodological limitations related to the design of the questionnaire. Specifically, an important finding from the analysis of the free-text responses was that participants interpreted ‘streamlining’ in different ways, and therefore, analysis of responses regarding the extent of overall support for streamlining should be interpreted with caution. In addition, although the questionnaire suggested that pre-MDT meetings would allow the selection of patients for discussion at the full MDT meeting, the free-text comments suggested that this was not clear to all respondents. Furthermore, analysis of the responses to Likert questions regarding support for particular approaches to streamlining was complicated by the design of these statements. Several statements combined more than one strategy (eg, use of protocols with no discussion at MDMs for some patients). This makes it hard to assess the level of support for each strategy in isolation. In addition, no statements were included to ascertain the level of support for some of the other approaches for streamlining suggested by participants. Finally, there were only small numbers of respondents from MDTs for some tumour types, so further investigation of the opinions of members of MDT for less frequent tumour types may be required.

Conclusions

This study has extended and complemented the previous analyses of these data.5 We confirmed that while there is broad support for approaches that enable MDM discussions to focus on more complex cases, this may not be appropriate for all MDTs; there was also a lack of consensus about the methods by which streamlining could be achieved. Participants were particularly concerned about some patients being excluded from full MDM discussion, which could compromise the quality and safety of patient care.

Our analyses agree with the conclusion from the previous analysis of these data that tumour type-specific guidance for the use of protocols should be developed to facilitate streamlining discussions.5 This will contribute to ongoing discussions about the development of this guidance. It was suggested that study participants were keen that this guidance should be developed at the local level and that it should consider the perspectives of members of MDT for different tumour types and those in different professions. It is also important that the meaning of streamlining and the various approaches that could be used to achieve are clarified and considered in developing this guidance. Finally, this work highlighted the need for the identification and implementation of appropriate evaluation methods and outcomes measures to ensure that decisions about the approaches used are based on the impact on the quality and safety of patient care. In the meantime, the use of tools, such as MDT-FIT, could facilitate individual MDTs to reach an agreement about appropriate solutions without compromising the quality and safety of patient care.34

Footnotes

Contributors: LH planned the analysis, led the quantitative analysis and drafted the manuscript; MZ led the qualitative analysis; RW and EP carried out initial data analysis and interpretation; CT and JG provided guidance on the objectives and interpretation; and all the authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: This was a secondary analysis of the data provided by CRUK, which was not supported by any specific project grant. EP’s contribution was funded by a King's Undergraduate Research Fellowship.

Competing interests: None of the authors has conflict of interest though CT and JG declare that both were members of the steering group that guided the development of the survey on which this manuscript is based, and both have previously received funding from NHS England for the development of a team training/feedback system for cancer MDTs through Green Cross Medical Ltd.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.

References

- 1.Independent Cancer Task Force Achieving world-class cancer outcomes: a strategy for England 2015-2020 UK: independent cancer Taks force, 2015. Available: http://bit.ly/1Idwf5W [Accessed 18 Dec 2018].

- 2.National Cancer Action Team The characteristics of an effective multidisciplinary team London: National cancer action team, 2010. Available: http://www.ncin.org.uk/mdt [Accessed 18 Dec 2018].

- 3.Lamb BW, Jalil RT, Sevdalis N, et al. Strategies to improve the efficiency and utility of multidisciplinary team meetings in urology cancer care: a survey study. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14 10.1186/1472-6963-14-377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saini KS, Taylor C, Ramirez A-J, et al. Role of the multidisciplinary team in breast cancer management: results from a large international survey involving 39 countries. Ann Oncol 2012;23:853–9. 10.1093/annonc/mdr352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Research UK Meeting patients' needs: improving the effectiveness of multidisciplinary team meetings in cancer services London: Cancer Research UK, 2017. Available: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/files/full_report_meeting_patients_needs_improving_the_effectiveness_of_multidisciplinary_team_meetings_.pdf [Accessed 18 Dec 2018].

- 6.Pillay B, Wootten AC, Crowe H, et al. The impact of multidisciplinary team meetings on patient assessment, management and outcomes in oncology settings: a systematic review of the literature. Cancer Treat Rev 2016;42:56–72. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prades J, Remue E, van Hoof E, et al. Is it worth reorganising cancer services on the basis of multidisciplinary teams (MDTs)? A systematic review of the objectives and organisation of MDTs and their impact on patient outcomes. Health Policy 2015;119:464–74. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cancer Research UK Cancer in the UK 2018 UK: Cancer Research UK, 2018. Available: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/files/state_of_the_nation_apr_2018_v2_0.pdf [Accessed 18 Dec 2018].

- 9.National Cancer ActionTeam National cancer peer review programme report 2010/2011 an overview of the findings from the 2010/2011 National cancer peer review of cancer services in England London, UK: National cancer action team, 2011. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-cancer-peer-review-programme-report-2010-11 [Accessed 18 Dec 2018].

- 10.den Herder-van der Eerden M, Ewert B, Hodiamont F, et al. Towards accessible integrated palliative care perspectives of leaders from seven European countries on facilitators, barriers and recommendations for improvement. J Integr Care 2017;25:222–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hahlweg P, Didi S, Kriston L, et al. Process quality of decision-making in multidisciplinary cancer team meetings: a structured observational study. BMC Cancer 2017;17 10.1186/s12885-017-3768-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rankin NM, Lai M, Miller D, et al. Cancer multidisciplinary team meetings in practice: results from a multi-institutional quantitative survey and implications for policy change. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2018;14:74–83. 10.1111/ajco.12765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosell L, Alexandersson N, Hagberg O, et al. Benefits, barriers and opinions on multidisciplinary team meetings: a survey in Swedish Cancer care. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18 10.1186/s12913-018-2990-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jalil R, Ahmed M, Green JSA, et al. Factors that can make an impact on decision-making and decision implementation in cancer multidisciplinary teams: an interview study of the provider perspective. Int J Surg 2013;11:389–94. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2013.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamb BW, Green JSA, Benn J, et al. Improving decision making in multidisciplinary tumor boards: prospective longitudinal evaluation of a multicomponent intervention for 1,421 patients. J Am Coll Surg 2013;217:412–20. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamb BW, Brown KF, Nagpal K, et al. Quality of care management decisions by multidisciplinary cancer teams: a systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:2116–25. 10.1245/s10434-011-1675-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corp IBM. IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamb BW, Sevdalis N, Benn J, et al. Multidisciplinary cancer team meeting structure and treatment decisions: a prospective correlational study. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:715–22. 10.1245/s10434-012-2691-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soukup T, Petrides KV, Lamb BW, et al. The anatomy of clinical decision-making in multidisciplinary cancer meetings: a cross-sectional observational study of teams in a natural context. Medicine 2016;95 10.1097/MD.0000000000003885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balasubramaniam R, Subesinghe M, Smith JT. The proliferation of multidisciplinary team meetings (MDTMs): how can radiology departments continue to support them all? Eur Radiol 2015;25:3679–84. 10.1007/s00330-015-3760-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Funnell F, Minns K, Reeves K. Comparing nurses' and doctors' prescribing habits. Nurs Times 2014;110:12–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soukup T, Lamb BW, Arora S, et al. Successful strategies in implementing a multidisciplinary team working in the care of patients with cancer: an overview and synthesis of the available literature. J Multidiscip Healthc 2018;11:49–61. 10.2147/JMDH.S117945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor C, Ramirez AJ. Can we reduce burnout amongst cancer health professionals? Eur J Cancer 2010;46:2668–70. 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamb BW, Sevdalis N, Taylor C, et al. Multidisciplinary team working across different tumour types: analysis of a national survey. Ann Oncol 2012;23:1293–300. 10.1093/annonc/mdr453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor S, Ramirez AJ. Multidisciplinary team members views about MDT working: results from a survey commissioned by the National cancer action team, 2009. Available: www.ncin.org.uk/view?rid=137 [Accessed 18 Dec 2018].

- 26.Trotman J, Trinh J, Kwan YL, et al. Formalising multidisciplinary peer review: developing a haematological malignancy-specific electronic proforma and standard operating procedure to facilitate procedural efficiency and evidence-based clinical practice. Intern Med J 2017;47:542–8. 10.1111/imj.13302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makary MA, Teams M. and Clinics: Better Care or Just More Care.(Editorial). Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chinai N, Bintcliffe F, Armstrong EM, et al. Does every patient need to be discussed at a multidisciplinary team meeting? Clin Radiol 2013;68:780–4. 10.1016/j.crad.2013.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munro AJ. Multidisciplinary team meetings in cancer care: an idea whose time has gone? Clin Oncol 2015;27:728–31. 10.1016/j.clon.2015.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor C, Shewbridge A, Harris J, et al. Benefits of multidisciplinary teamwork in the management of breast cancer. BCTT 2013;5 10.2147/BCTT.S35581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.KM K, Blazeby JM, Strong S, et al. Are multidisciplinary teams in secondary care cost-effective? A systematic review of the literature. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2013;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leo F, Venissac N, Poudenx M, et al. Multidisciplinary management of lung cancer: how to test its efficacy? J Thorac Oncol 2007;2:69–72. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31802bff56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pawson R, Tilley N, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation. London: Sage, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 34.MDT_FIT GCM, 2014. Available: www.mdtfit.co.uk [Accessed 18 Dec 2018].

- 35.Taylor C, Brown KB, Sevdalis N, et al. 4153 oral developing and testing a novel, evidence-based and User-tested toolkit for assessing and improving Teamworking in multidisciplinary cancer teams. Eur J Cancer 2011;47 10.1016/S0959-8049(11)71319-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]