Abstract

Despite being the second most common malignant bone tumor, Ewing's sarcoma remains uncommon in younger children and seldom seen in neonates and infants. Extraskeletal locations are even rarer, hardly ever suspected, and often misdiagnosed, causing delays in management. The histologic similarities of Ewing's sarcoma to more common pediatric small-blue-round-cell tumors such as lymphoma and neuroblastoma necessitate immunohistochemistry and molecular genetics for clinching the diagnosis. We report a soft-tissue Ewing's sarcoma in a 4-month-old female infant masquerading as a benign neck mass clinically, radiologically, cytologically, and intraoperatively. We also reviewed literature for any existing guidelines on when to biopsy neck masses in the pediatric population.

KEYWORDS: Ewing's sarcoma, infant, neck mass, pediatric

INTRODUCTION

Ewing's sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) is the second most common malignant bone tumor, with an incidence of 2.9/million, but uncommon in young children with a reported incidence of only 2.6% below 3 years and seldom seen in neonates and infants.[1,2] Extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma (EES) is rarer in infants, with only a few reported cases and is often misdiagnosed, leading to delays in treatment. We present our case of a soft-tissue Ewing's sarcoma in a 4-month-old baby, which apart from being extremely rare was masquerading as a benign neck mass clinically, radiologically, cytologically, and intraoperatively. We also reviewed the literature for any existing guidelines on when to biopsy pediatric neck masses, which are very commonly encountered by pediatricians and pediatric surgeons world over.

CASE REPORT

A 4-month-old female infant presented with left submandibular swelling noticed 3 weeks prior and gradually increasing in size. There was no associated fever or other constitutional symptoms. On examination, the baby was active, well nourished, and had a 2.5 cm × 2 cm left submandibular mobile swelling, firm in consistency, smooth-surfaced with well-defined margins, and superficial to the muscles [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Left submandibular mass, firm, smooth-surfaced with well-defined margins

Ultrasonography of the neck revealed a 2.8 cm × 2.0 cm well-defined hypoechoic lesion with no vascularity, whereas magnetic resonance imaging of the neck showed a 2.9 cm × 2.8 cm × 2.2 cm T1-isointense lesion and no associated lymphadenopathy. Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) of the mass was reported as a highly cellular smear showing monotonous population of small lymphocytes with coarse granular chromatin along with few centrocytes and centroblasts in a hemorrhagic background, suggestive of florid lymphoid hyperplasia.

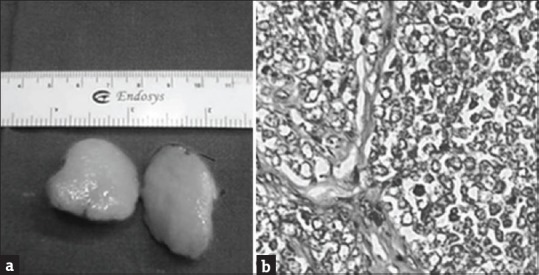

Excision biopsy was planned due to the slightly large size and atypical presentation. Operative findings showed a 2 cm × 3 cm firm, well-demarcated mass in the left submandibular triangle in the subcutaneous plane [Figure 2a]. There were no other lymph nodes noticed and no infiltration, and the mass could be easily excised in toto within 5–10 min.

Figure 2.

(a) Cut section of the tumor, 2 cm × 2.8 cm, fleshy and smooth in appearance. (b) Highly cellular tumor, lobules separated by fibrocollagenous septae, individual cell shows scanty cytoplasm, uniform round-to-oval vesicular nuclei with high mitotic activity (H and E, ×40)

Histopathology revealed a highly cellular, malignant, small-blue-round-cell tumor with no native tissue seen. Cells were arranged in lobules separated by fibrocollagenous septae and individual cell showed scanty cytoplasm, uniform to round-to-oval vesicular nuclei with high mitotic activity [Figure 2b]. There was capsular infiltration but no evidence of hemorrhage, necrosis, or lymphovascular invasion. Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD99, vimentin, and Bcl-2 but negative for leucocyte common antigen (LCA), desmin, CD3, CD20, CD30, and Tdt, and fluorescence in situ hybridization was negative for SYT (18q11.2) gene rearrangement, suggestive of Ewing's sarcoma.

Postoperative positron-emission tomography–computed tomography scan showed no residual tumor or metastasis. Adjuvant chemotherapy with alternating cycles of vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, and etoposide was started. As the baby developed two episodes of febrile neutropenia and extensive herpes zoster with chemotherapy, chemotherapy had to be stopped after three courses at the behest of the parents. However, the baby was placed under close surveillance. At 24-month follow-up, the baby was doing extremely well, growing adequately, with no evidence of recurrence.

DISCUSSION

Ewing's sarcoma belongs to the Ewing sarcoma family of tumors (ESFTs), which consists of small-round-blue-cell tumors, namely Ewing sarcoma, peripheral PNET, neuroepithelioma, atypical Ewing sarcoma, and Askin tumor.[2] Most tumors arise in the skeletal system, but occasionally they can occur in soft tissues and are called EESs. While EES commonly occurs in the extremities or deep soft tissues, cutaneous and subcutaneous locations have been rarely reported.

EES is exceedingly rare in newborns and infancy with only sporadic reports and is often misdiagnosed. Kim et al. reported three newborns with congenital PNET, all of whom were misdiagnosed initially due to histologic similarities to other pediatric small-blue-round-cell tumors such as lymphoma, neuroblastoma, alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, desmoplastic small-round-cell tumor, and poorly differentiated synovial sarcoma. They recommended immunohistochemistry and molecular genetics as a means to differentiate ESFT from other small-round-cell tumors.[2]

Maygarden et al. suggested that Ewing's sarcoma of the bone in children who are younger than 3 years at presentation represents an unusually young age group and comprises 2.6% of all patients registered in the Intergroup Ewing's Sarcoma Study.[1] We concur with Maygarden et al. that, though rare, Ewing's sarcoma must be considered in the differential diagnosis of small- blue- round-cell tumors, even in infants and toddlers.

It has also been noted that there exists a marked clinical variation between infants and the general Ewing's sarcoma patients with a striking predominance of female patients (P < 0.001) and a trend toward rib, pelvis, and proximal long bones in the young.[1] The overall survival rate of the infants was 56%, almost identical to that of older children. All infants who died of disease did so within 4 years, and extended follow-up as long as 9.9 years found no late deaths attributable to tumor.[2]

Furthermore, in this case, the EES mimicked a benign neck mass clinically, radiologically, cytologically, and even intraoperatively. At no point did we suspect a malignancy and hence could not counsel the parents preoperatively. Even intraoperatively, the mass was benign-looking, well-demarcated, nonadherent, and could be easily excised within a few minutes.

We reviewed literature for any available protocols on when to biopsy pediatric neck masses, but noted extreme heterogeneity in the evaluation and management of solid lateral neck masses between clinicians (pediatricians, pediatric surgeons, ENT surgeons, head-and-neck surgeons, etc.) with no clear guidelines.[3] On extensive literature search, we realized that there are conflicting opinions regarding the reliability of FNAC in treating pediatric neck masses with variations based on expertise of the cytopathologist, radiological findings, or suspicious factors such as size of the mass (>2 cm), location, and systemic features.[3,4,5] However, the patient did not overtly demonstrate any of the “suspicious” factors. Therefore, we would like to suggest that until the advent of a guideline approach or a more sensitive investigative modality, it appears that a high index of suspicion based on the clinician's experience and acumen may be the single important factor which can prevent delays in management of rare pediatric malignant neck masses.

CONCLUSIONS

Ewing's sarcoma has to be considered in the differential diagnosis of small-blue-round-cell tumors even in infants and toddlers and in both skeletal and extraskeletal locations. Pediatric neck masses are commonly encountered, but absolute guidelines for biopsy do not exist till date. Heterogeneity in the evaluation and management of solid lateral neck masses between clinicians is noticed and indicates the need for guideline approach. While careful history, physical examination, laboratory work-up, and diagnostic imaging must be used to guide the clinician in decision-making for biopsy, sometimes, a high index of suspicion based on the clinician's experience and acumen may be the single factor which can prevent delays in management of rare pediatric malignant neck masses.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Ms. Usharani, Department of Pediatric Surgery, for meticulous data collection and Department of Pathology, ESIC Super Speciality Hospital, for aid in detailed evaluation and microphotographs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maygarden SJ, Askin FB, Siegal GP, Gilula LA, Schoppe J, Foulkes M, et al. Ewing sarcoma of bone in infants and toddlers. A clinicopathologic report from the intergroup Ewing's study. Cancer. 1993;71:2109–18. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930315)71:6<2109::aid-cncr2820710628>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SY, Tsokos M, Helman LJ. Dilemmas associated with congenital Ewing sarcoma family tumors. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;30:4–7. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31815cf71f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nolder AR. Paediatric cervical lymphadenopathy: When to biopsy? Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;21:567–70. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Locke R, Comfort R, Kubba H. When does an enlarged cervical lymph node in a child need excision? A systematic review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78:393–401. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hafez NH, Tahoun NS. Reliability of fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) as a diagnostic tool in cases of cervical lymphadenopathy. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2011;23:105–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jnci.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]