Abstract

Background

Hypnotherapy is widely promoted as a method for aiding smoking cessation. It is intended to act on underlying impulses to weaken the desire to smoke, or strengthen the will to stop.

Objectives

To evaluate the effect and safety of hypnotherapy for smoking cessation.

Search methods

For this update we searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialized Register, and trial registries (ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform), using the terms "smoking cessation" and "hypnotherapy" or "hypnosis", with no restrictions on language or publication date. The most recent search was performed on 18 July 2018.

Selection criteria

We considered randomized controlled trials that recruited people who smoked and implemented a hypnotherapy intervention for smoking cessation compared with no treatment, or with any other therapeutic interventions. Trials were required to report smoking cessation rates at least six months after the beginning of treatment. Study eligibility was determined by at least two review authors, independently.

Data collection and analysis

At least two review authors independently extracted data on participant characteristics, the type and duration of hypnotherapy, the nature of the control group, smoking status, method of randomization, and completeness of follow‐up. These authors also independently assessed the quality of the included studies. In undertaking this work, we used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane.

The main outcome measure was abstinence from smoking after at least six months' follow‐up. We used the most rigorous definition of abstinence in each trial, and biochemically validated abstinence rates where available. Those lost to follow‐up were considered to still be smoking. We summarized effects as risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Where possible, we performed meta‐analysis using a fixed‐effect model. We also noted any adverse events reported.

Main results

We included three new trials in this update, which brings the total to 14 included studies that compared hypnotherapy with 22 different control interventions. The studies included a total of 1926 participants. Studies were diverse and a single meta‐analysis was not possible. We judged only one study to be at low risk of bias overall; we judged 10 studies to be at high risk of bias and three at unclear risk. Studies did not provide reliable evidence of a greater benefit from hypnotherapy compared with other interventions or no treatment for smoking cessation. Most individual studies did not find statistically significant differences in quit rates after six months or longer, and studies that did detect differences typically had methodological limitations.

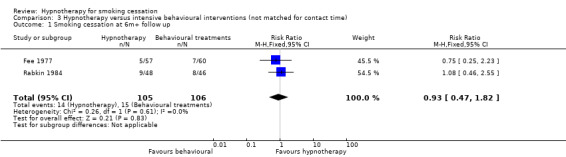

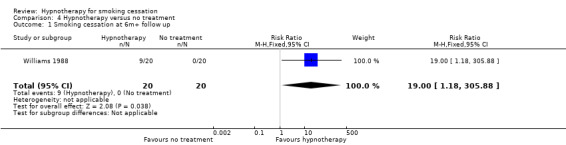

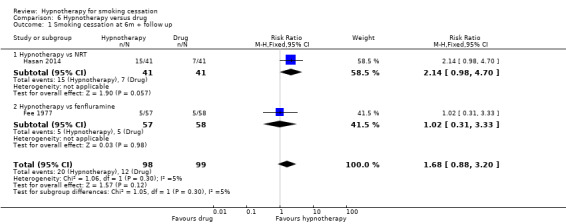

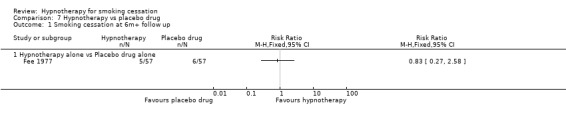

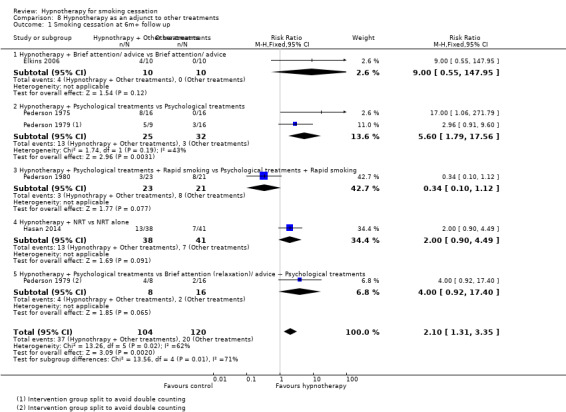

Pooling small groups of relatively comparable studies did not provide reliable evidence for a specific effect of hypnotherapy relative to controls. There was low certainty evidence, limited by imprecision and risk of bias, that showed no statistically significant difference between hypnotherapy and attention‐matched behavioural treatments (RR 1.21, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.61; I2 = 36%; 6 studies, 957 participants). Results were similarly imprecise, and also limited by risk of bias, when comparing hypnotherapy to intensive behavioural interventions (not matched for contact time) (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.82; I2 = 0%; 2 studies, 211 participants; very low certainty evidence). Results from one small study (40 participants) detected a statistically significant benefit of hypnotherapy compared to no intervention (RR 19.00, 95% CI 1.18 to 305.88), but this evidence was judged to be of very low certainty due to high risk of bias and imprecision. No significant differences were detected in comparisons of hypnotherapy with brief behavioural interventions (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.69; I² = 0%; 2 studies, 269 participants), rapid/focused smoking (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.43 to 2.33; I2 = 65%; 2 studies, 54 participants), and pharmacotherapies (RR 1.68, 95% CI 0.88 to 3.20; I2 = 5%; 2 studies, 197 participants). When hypnotherapy was evaluated as an adjunct to other treatments, the pooled result from five studies showed a statistically significant benefit in favour of hypnotherapy (RR 2.10, 95% CI 1.31 to 3.35; I² = 62%; 224 participants); however, this result should be interpreted with caution due to the high risk of bias across studies (four had a high risk or bias, one had an unclear risk), and substantial statistical heterogeneity.

Most studies did not provide information on whether data specifically relating to adverse events were collected, and whether or not any adverse events occurred. One study that did collect such data did not find a statistically significant difference in the adverse event ‘index’ between hypnotherapy and relaxation.

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence to determine whether hypnotherapy is more effective for smoking cessation than other forms of behavioural support or unassisted quitting. If a benefit is present, current evidence suggests the benefit is small at most. There is very little evidence on whether hypnotherapy causes adverse effects, but the existing data show no evidence that it does. Further large, high‐quality randomized controlled trials, and more comprehensive assessments of safety, are needed on this topic.

Plain language summary

Does hypnotherapy help people who are trying to stop smoking?

Background

Smoking is the leading cause of preventable illness and death worldwide. Stopping smoking greatly improves people's health, even when they are older. Different types of hypnotherapy are used to try and help people to quit smoking. Some methods try to weaken people's desire to smoke, strengthen their will to quit, or help them concentrate on a 'quit programme'. We reviewed the evidence on the effect of hypnotherapy in people who wanted to quit smoking.

Study characteristics

We found 14 studies comparing hypnotherapy with other approaches to help people stop smoking (including brief advice, or more intensive stop‐smoking counselling), or no treatment. Overall, 1926 people were included. Studies lasted at least six months. The studies varied greatly in terms of the treatments they compared, so it was difficult to combine their results. We searched for evidence up to 18 July 2018.

Key results

When we combined the results of six studies (with a total of 957 people) there was no evidence that hypnotherapy helped people quit smoking more than behavioural interventions, such as counselling, when delivered over the same amount of time. There was also no evidence that there was a difference between hypnotherapy and longer counselling programmes when we combined results from two studies (269 people). One study compared hypnotherapy with no treatment and found an effect in favour of hypnotherapy, but the study was small (40 people) and had issues with its methods, which means we cannot be certain about this finding. Most of the studies did not say if they also evaluated the safety of hypnotherapy. Five studies looked at adding hypnotherapy to existing treatments and found an effect, but the studies were at high risk of bias and there were large, unexplained differences in their findings. One study that compared hypnotherapy and relaxation found no difference in side effects.

Certainty of evidence

The evidence in this review ranges from low to very low certainty, as there was not enough information and many of the studies had issues with their designs.

There is no clear evidence that hypnotherapy is better than other approaches in helping people to stop smoking. If a benefit is present, current evidence suggests the benefit is small at most. Larger, high‐quality studies are needed.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Hypnotherapy versus behavioural treatments or no treatment for smoking cessation.

| Hypnotherapy versus behavioural treatments or no treatment for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: people who smoke Intervention: hypnotherapy Comparison: behavioural treatments or no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with Hypnotherapy | |||||

| Hypnotherapy versus attention‐matched behavioural treatments Smoking cessation at 6+ months follow‐up |

Study population |

RR 1.21 (0.91 to 1.61) |

957 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,2 |

||

| 150 per 1,000 |

182 per 1,000 (137 to 242) |

|||||

| Hypnotherapy versus brief attention/advice/smoking cessation education (not matched for contact time) Smoking cessation at 6+ months follow‐up |

RR 0.98 (0.57 to 1.69) |

269 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low3,4 |

|||

| 160 per 1,000 |

157 per 1,000 (91 to 271) |

|||||

| Hypnotherapy versus intensive behavioural interventions (not matched for contact time) Smoking cessation at 6+ months follow‐up |

Study population |

RR 0.93 (0.47 to 1.82) |

211 (2 studies) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low3,4 |

||

| 142 per 1,000 |

132 per 1,000 (67 to 258) |

|||||

| Hypnotherapy versus no treatment Smoking cessation at 6+ months follow‐up |

Study population |

RR 19.00 (1.18 to 305.88) |

40 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low3,4 |

||

| Non‐calculable (0 events in control group) | Non‐calculable | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level due to imprecision: fewer than 300 events overall 2 Downgraded one level due to risk of bias: three of the six included studies were judged to be at high risk of bias in at least one domain, and two were judged to be at unclear risk 3 Downgraded two levels due to imprecision: fewer than 100 events overall 4 Downgraded one level due to risk of bias: all studies contributing to the comparison were judged to be at high risk of bias

Background

Description of the condition

Tobacco smoking remains the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality worldwide (GBD 2016). Tobacco use leads to increased mortality through heart disease, cancers, and other conditions, and causes premature death in half of all regular users (WHO 2018). Worldwide, an estimated one billion people smoke, 80% of whom live in low‐ and middle‐income countries (WHO 2018). Among smokers who know smoking is hazardous to their health, most want to quit (WHO 2018).

Description of the intervention

Hypnotherapy has been recognized as a therapeutic tool by professional medical groups in several countries for many years (Kirsch 1995). Clinical research on hypnotherapy is limited, but some success has been reported for symptom reduction in irritable bowel syndrome (Whorwell 1991), asthma (Morrison 1988), and chronic pain (Hart 1994), and for improving quality of life in cancer patients (Newton 1982). There is, however, little consensus about how hypnotherapy might induce these effects. It is also recognized that treatment success could be influenced by other factors, such as the transference relationship between patient and therapist and the 'hypnotisability' of subjects (Perry 1979).

How the intervention might work

Potential rationale for hypnotherapy as a useful aid for smoking cessation is that, by acting on underlying impulses, it may weaken the desire to smoke, strengthen the will to stop, or improve the ability to focus on a treatment programme by increasing concentration (Spiegel 1993). Many different hypnotherapy techniques have been employed, but the most frequently used approaches are variants of the 'one session, three point' method developed by Spiegel. This method attempts to modify patients' perceptions of smoking by using the potential of hypnotherapy to induce deep concentration. During the session the smoker is instructed that: a) smoking is a poison, b) the body is entitled to protection from smoke, and c) there are advantages to life as a non‐smoker (Spiegel 1970). This approach also includes training in self‐hypnosis, which some posit may be as important as undergoing hypnosis by a therapist (Katz 1980). Self‐hypnosis can be used at will by the person trying to quit; in addition, compliance may be higher and costs lower because only one session is required. In uncontrolled studies, this method is associated with six‐month abstinence rates of between 20% and 35% (Spiegel 1993a).

Why it is important to do this review

Most of the older studies of hypnotherapy for smoking cessation are either case reports or poor‐quality uncontrolled trials, which show great variability in quit rates (4% to 88%) six months after treatment. Interpretation of these studies is complicated by the many different hypnotherapy regimens used and the variation in number and frequency of treatments (Holroyd 1980). The purpose of this review is to assess the effect of hypnotherapy for smoking cessation from all the relevant trials purporting to be randomized and controlled.

Objectives

To evaluate the effect and safety of hypnotherapy as a treatment for smoking cessation.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster‐randomized controlled trials (CRCTs).

Types of participants

We included people who wish to stop smoking, irrespective of gender, number of years smoking, or extent of nicotine dependence. We did not include studies of smokers who had recently quit, as these are included in a separate Cochrane Review (Livingstone‐Banks 2019).

Types of interventions

We included any trial of hypnotherapy for smoking cessation, compared with no treatment, or with any other therapeutic interventions. We reported the type and duration of therapy.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcome was abstinence from smoking (continuous, point prevalence or prolonged), assessed at least six months from the start of treatment. Validated abstinence based on biochemical markers, and abstinence based on self‐report by telephone and postal questionnaires were accepted. Where multiple measures of abstinence were reported we used the most stringent, i.e. continuous over point prevalence, and validated over self‐reported.

We also looked for any adverse events (AEs) reported in the studies.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified all reports that might describe RCTs of hypnotherapy for smoking cessation from the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialized Register, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. The most recent search was performed on 18 July 2018). At the time of the search, the Register included the results of searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL), Issue 1, 2018; MEDLINE (via OVID) to update 20180531; Embase (via OVID) to week 201824; and PsycINFO (via OVID) to update 20180528. See the Tobacco Addiction Group website for full search strategies and list of other resources searched. There were no language or publication date restrictions in the search.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

At least two review authors independently checked all of the trials identified against the inclusion criteria, by screening titles and abstracts and then by reading through the full‐text copies. The lists of included studies were then compared and any disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction and management

For each included trial, at least two review authors used a standardized data extraction form to independently record information on study methodology, randomization method, participant demographics, intervention details, smoking cessation rates after six months or more, follow‐up rates, and adverse events. We also extracted information on sample size calculation and baseline equivalence.

Data extraction forms and 'Risk of bias' assessments were then compared, and we resolved any discrepancies by discussion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

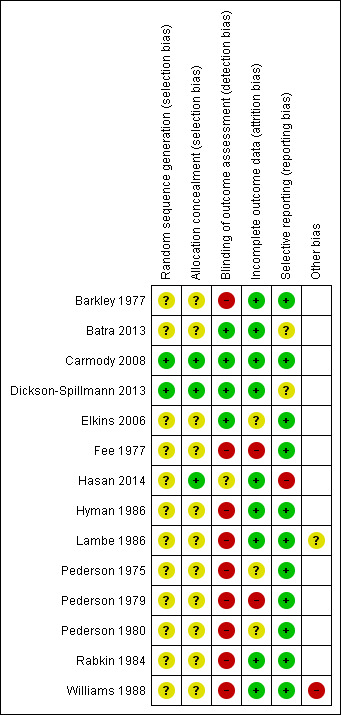

Two review authors independently assessed the trials using the Cochrane 'Risk of Bias' tool (Higgins 2011). Six elements were assessed: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of outcome assessors (detection bias); incomplete outcome data; selective reporting; and potential for other biases.

Measures of treatment effect

For cessation data, if the results were not based on an intention‐to‐treat analysis but had 'loss to follow‐up' recorded, we recalculated the results to include all randomized participants (except those deceased), and assumed those lost to follow‐up to be continuing smokers. We used the strictest criteria for abstinence, preferring sustained over point prevalence measures. We summarized individual study results as a risk ratio (RR), calculated as: (number of quitters in intervention group/number randomized to intervention group)/(number of quitters in control group/ number randomized to control group). An RR greater than 1.0 indicates a higher rate of quitting in the treatment group than in the control group.

Adverse event data was sparsely reported. Where available, we report it narratively in the text in the form provided by the original authors.

Unit of analysis issues

We planned to assess cluster‐randomized studies on a case‐by‐case basis. Only one study was cluster‐randomized; in this case, the authors allowed for clustering so we used the data reported by the study authors, without further adjustment.

Dealing with missing data

For studies published after the year 2005, we attempted to contact the study authors for any missing or unclear information. Statistical methods for dealing with loss to follow‐up are described below.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We tested for statistical heterogeneity, and where we found it (P value of the Chi2 test less than 0.05, or I² value greater than approximately 60% to 70%) we considered whether it might be accounted for by characteristics of the interventions, participant populations, or ways in which outcomes were assessed or defined.

Assessment of reporting biases

Had sufficient studies been available, we would have created a funnel plot to explore possible publication bias.

Data synthesis

For comparisons where more than one eligible trial was identified, we performed meta‐analysis using a Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect method to estimate a pooled RR with 95% confidence intervals (Mantel 1959), as per standard methods of the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction review group.

We grouped studies into the following comparisons, according to the characteristics of the 'control' condition. We grouped studies that tested hypnotherapy as an adjunct to other treatments separately (e.g. studies in which both study arms received a treatment, and the intervention arm also received hypnotherapy).

Hypnotherapy versus attention‐matched behavioural interventions

Hypnotherapy versus brief behavioural interventions (not matched for contact time)

Hypnotherapy versus intensive behavioural interventions (not matched for contact time)

Hypnotherapy versus no treatment

Hypnotherapy versus rapid/focused smoking

Hypnotherapy versus drug

Hypnotherapy versus placebo drug

Hypnotherapy as an adjunct to other treatments

Trials with multiple treatment or control arms contributed to more than one comparison. Where use of separate pair‐wise comparisons resulted in the same group being used in subgroups contributing to the same analysis, the number of participants in the shared group was split across the two comparisons, in line with the standard methods of the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group. We used forest plots to display the data in all comparisons.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Within the above groups, we subgrouped studies by nature of intervention and nature of comparator. We had originally planned to conduct subgroup analyses based on hypnotherapy type and intensity but sufficient data were not available.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses removing studies judged to be at high risk of bias.

'Summary of findings' table

We created a 'Summary of findings' table for the following comparisons: hypnotherapy versus attention‐matched behavioural interventions; hypnotherapy versus brief behavioural interventions; hypnotherapy versus intensive behavioural interventions; and hypnotherapy versus no treatment. We assessed the certainty of the evidence for these comparisons using the five GRADE domains, in accordance with standard Cochrane guidance: study limitations; consistency of effect; indirectness; imprecision; and publication bias (Higgins 2011).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

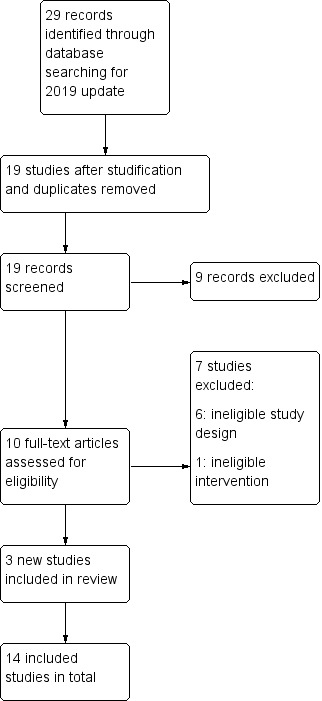

The PRISMA flow chart for records identified and screened for this review update is shown in Figure 1. Literature searches for this update returned 29 records, of which 10 were removed as duplicates or after studification; we screened the titles and abstracts of the remaining 19 records, and excluded a further nine studies. We performed full‐text assessments for 10 studies, and excluded seven. Thus, for the present update we identified three new studies for inclusion — Batra 2013; Dickson‐Spillmann 2013; Hasan 2014 — making a total of 14 included studies. All included studies were in English, with the exception of an unpublished report (Batra 2013), for which an English translation was provided by the author. We did not identify any ongoing studies.

1.

Study flow diagram for 2019 update

Included studies

The 14 included studies include data from 1926 participants. Additional details of the included studies are presented in the 'Characteristics of included studies' tables. Six studies were conducted in the USA, four in Canada, and one each in the UK, Australia, Germany and Switzerland. All of the included studies were parallel randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with follow‐up length of at least six months; one study was a parallel‐group, cluster‐RCT (Dickson‐Spillmann 2013). Sample sizes were typically small, and varied from 20 to 360 participants. Only Batra 2013, Carmody 2008, and Dickson‐Spillmann 2013 included more than 100 people in each arm, and only Dickson‐Spillmann 2013 and Lambe 1986 reported an appropriate sample size calculation. The studies typically included participants who smoked 20 to 40 cigarettes per day (CPD). There were more female than male participants, and the average age was between 30 and 40 years.

The studies varied in the method of hypnotic induction used, number of hypnotherapy sessions, and duration of hypnotic treatments. Nine studies (Barkley 1977; Batra 2013; Carmody 2008; Dickson‐Spillmann 2013; Elkins 2006; Hasan 2014; Hyman 1986; Rabkin 1984; Williams 1988) mentioned the method or described the details of induction used, whilst the rest did not describe the technique (see Characteristics of included studies for further detail). The number of hypnotherapy sessions varied from a single session (Dickson‐Spillmann 2013; Hasan 2014; Pederson 1975; Pederson 1979; Pederson 1980; Rabkin 1984; Williams 1988), to up to eight sessions (Elkins 2006). One study did not report the number of sessions (Fee 1977). The total duration of hypnosis used in the studies ranged from 30 minutes to nine hours. Seven studies provided hypnotherapy in a group format (Barkley 1977; Batra 2013; Dickson‐Spillmann 2013; Pederson 1975; Pederson 1979; Pederson 1980; Williams 1988).

Although there was diversity in the interventions, we were unable to conduct subgroup analyses based on hypnotherapy type and intensity because there was also variation in the control conditions, so very few studies were directly comparable. Some studies compared hypnotherapy alone against more than one intervention; some studies compared hypnotherapy plus other therapies against other therapies. Only one study compared hypnotherapy with a no‐treatment waiting‐list comparison group (Williams 1988). Two other studies had waiting‐list controls, but we could not include them in this comparison because treatment was offered before the end of the follow‐up period (Hyman 1986; Rabkin 1984). Six studies compared hypnotherapy with an attention‐matched behavioural intervention (Barkley 1977; Batra 2013; Carmody 2008; Dickson‐Spillmann 2013; Hyman 1986; Williams 1988). Three studies compared hypnotherapy with interventions not matched for contact time; Lambe 1986 and Rabkin 1984 compared hypnotherapy with brief behavioural interventions, and Fee 1977 and Rabkin 1984 compared hypnotherapy to more intensive behavioural treatments. One study, Hasan 2014, compared hypnotherapy plus counselling with nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) plus counselling and with a combination of hypnotherapy, NRT and counselling. Two trials compared hypnotherapy with rapid/focused smoking ( Barkley 1977; Hyman 1986), and one compared hypnotherapy with a specific drug (fenfluramine), and with a placebo (Fee 1977).

Five studies compared 'hypnotherapy plus other therapies' with identical therapies without the hypnotherapy component (e.g. evaluated hypnotherapy as an adjunct to other treatments). Of these, Elkins 2006 compared a combination of hypnotherapy, self‐help materials and supportive calls against self‐help materials and supportive calls; Pederson 1975 and Pederson 1979 compared hypnotherapy used in conjunction with counselling against counselling alone; Pederson 1980 compared hypnotherapy in conjunction with rapid smoking and counselling, against rapid smoking and counselling alone; and Hasan 2014 compared hypnotherapy plus NRT versus NRT alone.

Excluded studies

We excluded eight randomized studies because they had follow‐up at fewer than six months (Casmar 2003; Cornwell 1981; Perry 1979; Rodriguez 2007; Schubert 1983; Spanos 1993; Spanos 1995; Valbo 1995). One randomized study was excluded because participants were smokers who had already quit, hence this was a relapse‐prevention study (Carmody 2017); one randomized study of a bespoke smoking cessation intervention was excluded as hypnotherapy was not part of the intervention. We excluded four controlled studies because they were not randomized (Bastien 1983; Hasan 2007; Javel 1980; MacHovec 1978), and ten studies because they had no control group that did not receive hypnotherapy (Ahijevych 2000; Crasilneck 1968; Dedenroth 1968; Frank 1986; Johnson 1994; Katz 1978; Owens 1981; Perry 1975; Riegel 2013; Spiegel 1993). We excluded Tindle 2006 because the control group received the same intervention 12 weeks post‐randomization. Four records were meta‐analyses (Barnes 2010; Green 2006; Pierson 2016; Tahiri 2012), one of which also did not refer specifically to hypnotherapy interventions (Pierson 2016). Richard 2002 was a descriptive report and not a controlled trial; Sood 2006 and Thomas 2015 were cross‐sectional surveys rather than RCTs.

Risk of bias in included studies

A summary of 'Risk of bias' judgements for each study can be seen in Figure 2. Only Carmody 2008 was judged to be at an overall low risk of bias (low risk of bias across all domains). We judged three studies to be at an overall unclear risk of bias (Batra 2013; Dickson‐Spillmann 2013; Elkins 2006), and we judged the remainder to be at high risk of bias overall. Reasons for individual high 'Risk of bias' judgements are described below.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

We judged two studies to be at low risk of selection bias (Carmody 2008; Dickson‐Spillmann 2013); the remaining studies were judged to be at unclear risk of selection bias as insufficient detail was provided. All the included studies mentioned randomization; two reported the method in sufficient detail to assess whether sequence generation was adequate (Carmody 2008; Dickson‐Spillmann 2013), and three reported sufficient information to assess whether there was adequate allocation concealment (Carmody 2008; Dickson‐Spillmann 2013; Hasan 2014). We contacted the first author of Carmody 2008 for more information on the randomization method, and their response indicated adequate sequence generation and allocation concealment.

Detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment)

Following the standards of the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group, we assessed risk of detection bias based on whether or not the outcome was biochemically validated since, due to the nature of the intervention, blinding was often not possible. If biochemically validated data were not available, we also considered whether differential misreport was likely (e.g. if participants were aware of whether or not the treatment they were receiving was the intervention or control). We judged nine studies to be at high risk of bias for this domain, four to be at low risk, and one to be at unclear risk.

Carmody 2008 validated self‐reported success using saliva cotinine concentrations, or spousal proxy; Dickson‐Spillmann 2013 used saliva cotinine; Hasan 2014 used urinary cotinine or sought confirmation of abstinence from a household member; and Batra 2013 and Elkins 2006 used carbon monoxide or saliva cotinine. In cases where validation of abstinence was carried out we made a judgement of low risk of bias, except for Hasan 2014 where it was unclear how many participants had biochemical validation (hence we assigned a judgement of unclear risk of bias for this domain). Although two studies measured serum thiocyanate concentrations during the intervention, in both cases abstinence at six months was based on self‐report (Hyman 1986; Rabkin 1984). The other studies used self‐report obtained by a personal or telephone interview or by postal questionnaire, or did not state the method of follow‐up. In cases where self report was not validated, we made a judgement of high risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Nine studies reported the number of participants lost to follow‐up and the assumptions made about their smoking status in the analyses. We judged these studies to be at low risk of attrition bias. Of the remaining studies, we judged three to be at unclear risk of bias and two to be at high risk.

Three studies by Pederson and colleagues did not report whether any participants were lost to follow‐up (Pederson 1975; Pederson 1979; Pederson 1980), and Elkins 2006 did not report the number lost to follow‐up by group. Therefore, we assumed loss to follow‐up was equally divided when calculating back from percentages. One study reported loss to follow‐up rates and these were high and substantially different across groups; we judged the study to be at high risk of attrition bias (Fee 1977). One study used a household proxy to confirm abstinence where a urine sample for the participant was not provided; however, it was not reported how many participants this was done for and whether there was any difference in the number of participants this was done for in each group; we judged this study to be at unclear risk of attrition bias (Hasan 2014).

Selective reporting

We judged one study to be at high risk, two to be at unclear risk, and the remainder to be at low risk of reporting bias.

One study had a published protocol (Dickson‐Spillmann 2013). Three studies had trial registration numbers — Batra 2013 (trial number NCT01129999), Dickson‐Spillmann 2013 (trial number ISRCTN72839675), and Hasan 2014 (trial number NCT01791803) — though only Dickson‐Spillmann 2013 reported this number in the published paper. We judged Batra 2013 and Dickson‐Spillmann 2013 to be at unclear risk of selective reporting: for Batra 2013, some outcomes described in the methods were not reported and it was unclear why; and for Dickson‐Spillmann 2013, adverse event (AE) data were presented for two weeks but not for six months, and again the reason for this was unclear. We judged Hasan 2014 to be at high risk of bias for selective reporting due to deviations from their analysis plan. Other studies reported the outcomes described in their methods section and we judged them to be at low risk of bias for this domain.

Other potential sources of bias

We judged Lambe 1986 to be at unclear risk of other bias as there were significant baseline imbalances on characteristics known to be associated with smoking cessation, and analyses did not investigate this. We judged Williams 1988 to be at high risk of other bias as they used a waiting list control; the control group was aware they would later receive the intervention, which may have discouraged quitting in this arm. We did not identify any other potential sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

There was variation in the intensity of the hypnotherapy tested, little information on the types of hypnotherapy used, and large variation in the nature of the control interventions. Therefore, we did not perform an overall meta‐analysis of all forms of hypnotherapy, nor provide an overall summary estimate of the effect of hypnotherapy. Comparisons are specified below.

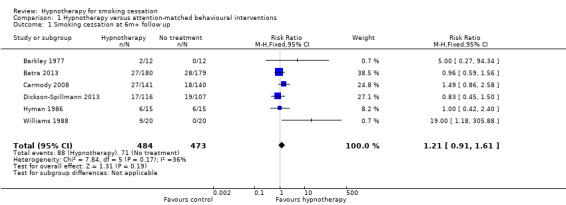

Comparison 1: hypnotherapy versus attention‐matched behavioural interventions

We included six trials, with a total of 957 participants, in this analysis (Barkley 1977; Batra 2013; Carmody 2008; Dickson‐Spillmann 2013; Hyman 1986; Williams 1988). There was no overall difference in smoking cessation rates between groups at six months or greater follow‐up (risk ratio (RR) 1.21, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.91 to 1.61; I² = 36%; 6 studies, 957 participants; Analysis 1.1). Only one very small trial of 40 participants showed a statistically significant increase in the smoking cessation rate for the hypnotherapy group, compared with the control that consisted of a single discussion session (2.5 hours in duration) (Williams 1988). However, this effect was very imprecise (RR 19.00, 95% CI 1.18 to 305.88) and we judged this study to be at high risk of bias.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hypnotherapy versus attention‐matched behavioural interventions, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at 6m+ follow up.

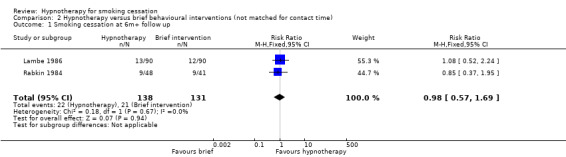

Comparison 2: hypnotherapy versus brief behavioural interventions (not matched for contact time)

Two trials compared hypnotherapy alone versus brief behavioural interventions (attention/advice/smoking cessation education alone) (Lambe 1986; Rabkin 1984). There was no difference in smoking cessation rates at six months or greater follow‐up across study groups (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.69; I² = 0%; 2 studies, 269 participants; Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Hypnotherapy versus brief behavioural interventions (not matched for contact time), Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at 6m+ follow up.

Comparison 3: hypnotherapy versus intensive behavioural interventions (not matched for contact time)

A further two trials compared hypnotherapy alone with more intensive behavioural treatments (not matched for contact time) (Fee 1977; Rabkin 1984). No significant difference in smoking cessation rates was detected (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.82; I2 = 0%; 2 studies, 211 participants; Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Hypnotherapy versus intensive behavioural interventions (not matched for contact time), Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at 6m+ follow up.

Comparison 4: hypnotherapy versus no treatment

One small trial with 20 participants in each arm compared hypnotherapy with a waiting list control (and also had a contact‐matched arm, discussed above) (Williams 1988). There was a significantly higher 12‐month point prevalence cessation rate for hypnotherapy than for the no‐treatment control group, in which there were no quitters (RR 19.00, 95% CI 1.18 to 305.88; 1 study, 20 participants; Analysis 4.1); however, confidence intervals were very wide and we judged this study to be at high risk of bias. We did not include a second trial with a waiting list control in this comparison because the intervention arm confounded hypnotherapy and counselling (Pederson 1975). A third trial that included a 'self‐quit' arm was also omitted from this comparison, as the individuals in the self‐quit arm had declined intervention and were not randomly assigned (Hasan 2014).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hypnotherapy versus no treatment, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at 6m+ follow up.

Comparison 5: hypnotherapy versus rapid/focused smoking

Two trials compared hypnotherapy to rapid smoking (Barkley 1977; Hyman 1986). The analyses showed no significant difference in smoking cessation rates between groups (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.43 to 2.33; I2 = 65%; 2 studies, 54 participants; Analysis 5.1). There was evidence of moderate heterogeneity (I² = 65%).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Hypnotherapy versus rapid/focused smoking, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at 6m+ follow up.

Comparison 6: hypnotherapy versus drug

Two trials compared hypnotherapy to a form of pharmacotherapy (Fee 1977; Hasan 2014). Hasan 2014 compared hypnotherapy to nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), and both groups also received counselling; this resulted in a RR of 2.14 (95% CI 0.98 to 4.70; 82 participants). Fee 1977 compared hypnotherapy to fenfluramine, which resulted in a RR of 1.02 (95% CI 0.31 to 3.33; 115 participants). When the two trials were pooled, there was no difference in smoking cessation rates between groups at six months or greater follow‐up (RR 1.68, 95% CI 0.88 to 3.20; I² = 5%; 2 studies, 197 participants; Analysis 6.1). There was no significant heterogeneity. Marketing authorisations for fenfluramine were withdrawn in the 1990s following an association between use of fenfluramine and valvular heart disease.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Hypnotherapy versus drug, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at 6m + follow up.

Comparison 7: hypnotherapy versus placebo drug

This analysis only included one trial (Fee 1977), which did not detect a significant difference between hypnotherapy and placebo pharmacotherapy (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.27 to 2.58; 114 participants; Analysis 7.1).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Hypnotherapy vs placebo drug, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at 6m+ follow up.

Comparison 8: hypnotherapy as an adjunct to other cessation interventions

The last comparison included five trials that compared hypnotherapy combined with other treatments versus these other treatments alone. We divided the trials into subgroups depending on the category of the other treatments. Overall, the pooled result showed a statistically significant benefit in favour of hypnotherapy (RR 2.10, 95% CI 1.31 to 3.35; 5 studies, 224 participants; Analysis 8.1); however, this result should be interpreted with caution due to high risk of bias across studies (four had a high risk or bias, one had an unclear risk), and substantial statistical heterogeneity (I² = 62%). Results of the contributing subgroups are described below.

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Hypnotherapy as an adjunct to other treatments, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at 6m+ follow up.

A single trial, involving 20 smokers, compared multi‐session hypnotherapy plus self‐help materials and telephone calls versus self‐help materials and telephone calls alone. No participants in the attention/advice‐alone group quit smoking, and the resulting confidence intervals were very wide (RR 9.00, 95% CI 0.55 to 147.95; 1 study, 20 participants; Analysis 8.1).

Two trials, with a total of 65 smokers, compared hypnotherapy plus counselling versus counselling alone (Pederson 1975; Pederson 1979). Pooling these studies using the adjusted number of participants (see Data synthesis) indicated a benefit of a hypnotherapy session as an adjunct to counselling, though the estimate was imprecise (RR 5.60, 95% CI 1.79 to 17.56; I² = 43%; 2 studies, adjusted number of participants = 57; Analysis 8.1).

A single trial, with 44 smokers, compared hypnotherapy combined with psychological treatments and rapid smoking treatments versus a combination of psychological and rapid smoking treatments (Pederson 1980). This trial did not detect any benefit of the additional hypnotherapy (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.10 to 1.12; 1 study, 44 participants; Analysis 8.1).

One trial, with 79 participants, compared a single session of individualized hypnotherapy in addition to at least one month's treatment with NRT and counselling versus the same NRT and counselling protocol (Hasan 2014). The analysis did not show a benefit of the additional hypnotherapy (RR 2.00; 95% CI 0.90 to 4.49; 1 study, 79 participants; Analysis 8.1).

One trial, involving 33 smokers, compared a single session of group hypnosis for smoking cessation versus a single session of hypnosis for relaxation, during which no suggestions were made about smoking (thus, this arm served as a control for the placebo effects of undergoing a hypnosis session) (Pederson 1979). Both arms also received multi‐session group‐based cessation counselling. The effect estimate was imprecise but favoured the intervention (RR 4.00, 95% CI 0.92 to 17.40; 1 study, adjusted number of participants = 24; Analysis 8.1). We judged this study to be at high risk of bias.

Adverse events

Dickson‐Spillmann 2013 described how AE data were collected (a list of AEs that included common symptoms not usually considered associated with nicotine withdrawal, and rated by participants using a four‐point scale). This study reported AE data for one of the two data collection points (two‐week follow‐up); there was no statistically significant difference in the AE ‘index’ between the hypnosis and relaxation groups. Barkley 1977 did not describe how AE data were collected, but reported the number of participants in the rapid smoking group who had vomited. Reports of the other 12 studies did not provide information on whether or not data specifically relating to AEs were collected, and whether or not any AEs occurred.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The 14 studies in this review do not demonstrate evidence of a greater long‐term benefit of hypnotherapy when compared to other interventions, or to no intervention, for smoking cessation. Most studies did not detect significant differences in quit rates at six months or longer. The studies were very diverse so we could not combine them in a single meta‐analysis; pooling small groups of relatively comparable studies did not provide evidence for any specific effect of hypnotherapy. This was true when hypnosis was compared with attention‐matched behavioural interventions, non‐attention‐matched brief interventions, or intensive behavioural interventions. When hypnosis was evaluated as an adjunct to existing treatments a statistically significant effect was detected; however, four of the five studies contributing to this analysis were at high risk of bias, and statistical heterogeneity was substantial. Any individual studies that did find higher quit rates for hypnotherapy, compared with controls, were small and had other methodological weaknesses.

This update includes three new trials that, collectively, contribute over 700 trial participants to the review (Batra 2013; Dickson‐Spillmann 2013; Hasan 2014). The largest trial involved 360 participants randomized to receive six sessions of group hypnotherapy or group cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) (Batra 2013). There was no significant difference in abstinence rates between the interventions at 12‐month follow up. As the control group received an intervention that has been found to be more effective than self‐help in achieving smoking cessation (Stead 2017), the absence of a significant difference between hypnotherapy and CBT might be interpreted as evidence of equivalence. However, this is not supported by evidence across the other comparisons in this review (which demonstrates a lack of effect), and the confidence intervals span both significant potential benefit and clinically relevant worsening of effect in comparison to CBT, suggesting that further research could change the effect estimate.

These studies provide scant information on the frequency and type of AEs experienced by participants. The one study that described how AE data were collected reported no statistically significant difference in the AE ‘index’ between the hypnosis and relaxation groups at two‐week follow‐up (Dickson‐Spillmann 2013). One other study reported that all participants in the rapid smoking group had vomited at least once by the end of the two‐week treatment (Barkley 1977). The other 12 studies provided no information on monitoring or occurrence of AEs.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We followed standard Cochrane methods to undertake this review update. The previous update of this review included a funnel plot of studies comparing hypnotherapy with attention/smoking cessation advice, which appeared to indicate potential publication bias (Barnes 2010). The funnel plot has been removed for this update, as such analyses are not recommended where fewer than ten studies are included in meta‐analyses. The largest trial included in this update, and the largest study in the review overall, is unpublished and was identified through searching a clinical trials registry (360 participants; Batra 2013). The other two new trials included in this update also had records identified in clinical trials registries (Dickson‐Spillmann 2013; Hasan 2014). The extent to which this reflects current practice among hypnotherapy researchers is not known, and therefore the potential for publication bias needs to be considered.

If hypnotherapy can increase the likelihood of quitting compared to no intervention or brief advice, it may be due to non‐specific factors such as extended contact with a therapist. The absence of a suitable placebo for hypnotherapy to control for the non‐specific effects makes evaluation difficult; however, from a public health point of view, this non‐specific expectation effect is valuable and, if it existed, would help people stop smoking, whether or not hypnotherapy is effective. Pederson 1979 did include two arms intended to investigate the non‐specific elements of hypnotherapy. One arm received a hypnosis session that was presented as an aid to relaxation, and the other controlled for the therapist presence by using a video presentation for the hypnotherapy session. Future studies should consider what approaches can be used to match for therapist contact and encouragement to stop smoking.

Certainty of the evidence

We judged the evidence from trials of hypnotherapy to be of low, or very low, certainty. We performed a GRADE assessment of the certainty of the evidence using the approach recommended by Cochrane (Higgins 2011). We judged the evidence for hypnotherapy versus attention‐matched behavioural treatments to be of low certainty because of imprecision (there was a small number of events overall, and wide confidence intervals), and because of risk of bias (we judged three of the six included studies to be at high risk of bias, and two to be at unclear risk). We judged the evidence for the other comparisons (hypnotherapy versus brief attention/advice/smoking cessation education not matched for contact time, versus intensive behavioural interventions, and versus no treatment) to be of very low certainty because of imprecision and because all the contributing studies were judged to be at high or unclear risk of bias. Many studies were conducted before improvements in the standard of study design and reporting for smoking cessation trials was seen in the 1990s. Biochemical validation of self‐reported quitting was only used in the five most recent studies, all of which were conducted since the year 2000.

Potential biases in the review process

The comprehensive searches for this update are current to 18 July 2018. In conducting this review update, we rearranged the comparisons in order to better reflect the nature of the comparator treatments, and to better align this review with other Cochrane Reviews of smoking cessation interventions. It is possible that different results would have been obtained if the studies had been grouped differently; however, most of the studies provided no evidence of an effect, and our certainty in the evidence ranged from low to very low primarily due to study limitations, so it is unlikely that any analysis would change our overall conclusions.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Tahiri and colleagues conducted a random‐effects meta‐analysis of RCTs of 'alternative' smoking cessation interventions, including hypnotherapy (Tahiri 2012). They conducted literature searches up to December 2010, so their review was prior to the completion of the three new trials included in our present review update. Their meta‐analysis pooled results from four trials of hypnotherapy (Elkins 2006; Lambe 1986; Pederson 1979; Williams 1988; 273 participants), all of which are included in this review. It is not clear why Tahiri 2012 did not identify or include the other seven trials included in this review, but this may be because they had stricter inclusion criteria. Only one of the four included trials described using biochemical validation of smoking status, and the included studies investigated a range of different hypnotherapy interventions and controls. The meta‐analysis result showed no significant beneficial effect of hypnotherapy and moderate heterogeneity (odds ratio 4.55, 95% CI 0.98 to 21.01; I2 = 67%). This is consistent with our findings; however, the authors of the meta‐analysis draw more positive conclusions, based on the non‐significant trend in favour of hypnotherapy.

The highly significant effects of hypnotherapy on smoking cessation reported by past uncontrolled studies (e.g. Dedenroth 1968) have not been supported by our analyses of RCTs. Although many therapists offer hypnotherapy for smoking cessation, and it continues to be a popular choice amongst smokers seeking treatment, there is recognition that the success rates quoted by practitioners are likely to be exaggerated (Handel 2010; Yager 2010). Encouraging results reported in uncontrolled studies may be due to the motivation of those presenting for treatment, or may not reflect likely long‐term success or dropout rates.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is insufficient evidence to support the use of hypnotherapy as a specific treatment for smoking cessation.

Implications for research.

Since hypnotherapy is often used as an aid to smoking cessation, there is a need for large, high‐quality trials to establish its effects. Where trials are undertaken, the type of hypnotherapy assessed needs to be clearly defined and described. Trials should include comparisons with no or minimal treatment and comparisons with active interventions, ideally matching for therapist contact time. Smoking cessation should be biochemically validated.

Feedback

Hypnotherapy versus NRT or bupropion

Summary

The comment asked whether anyone knew of any formal comparisons of hypnotherapy with treatments such as NRT or bupropion

Reply

We know of no randomized controlled trials comparing hypnotherapy with NRT or bupropion (Zyban) but we eagerly await such reports. We agree that it is important to compare different methods of smoking cessation. At the moment, only nine trials have been identified, and overall these have not shown that hypnotherapy has a greater effect on six‐month quit rates than other interventions or indeed no treatment. The small number of trials and their heterogeneity mean, however, that the jury is still out, and further data from adequately powered randomized studies is urgently needed.

Contributors

Neil Abbot

Losses to follow up

Summary

The commenter asked whether the estimates changed significantly if those lost to follow up were excluded rather than counted as continuing smokers

Reply

This contribution raises an interesting and important point. The inclusion or otherwise of those lost to follow‐up is the concern of intention to treat analysis (ITT) which is comprehensively discussed in Section 8.4 of the Reviewer's handbook (available on the web at http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/homepages/106568753/handbook.pdf ). The ideal strategy is to compare the groups exactly as randomised, but if data on some participants are lost for a variety of reasons, this can be impossible. ITT analysis aims to include all participants randomized into a trial irrespective of what happened subsequently. ITT analyses are generally preferred as they are unbiased, and also because they address a more pragmatic and clinically relevant question. It is the view of the Collaboration that ITT analysis delivers the most robust evidence and is to be preferred over less conservative approaches, and it explicitly adopts this approach in its reviews wherever possible. In the case of smoking cessation, the convention is to treat patients lost to follow‐up as continuing smokers. Some people may consider this inappropriate since we may be attributing the continuation of smoking to people who have actually quit. However, first, we are dealing here with randomised trials with a hypnotherapy and a control intervention, and this assumption is made for both the treatment and the control arms of each study, so it is thus unlikely that the use of ITT will adversely affect the treatment arm compared with the control arm. Second, the decision to assume that those lost to follow‐up are continuing smokers is based on clinical judgement as to what would be the most likely outcome, and most professionals would agree that this assumption is not unreasonable. Ideally, we would compute both ways, i.e. assuming that those lost to follow up were, first, continuing smokers and then, second, quitters, and perform a sensitivity analysis. Another option would be to analyse as you have suggested, using only the available data, i.e. excluding losses to follow up. Of the nine included studies in the current review, four only present an ITT analysis with insufficient information to perform an available‐data analysis (the Pederson studies and the Williams trial). None of the remaining five studies achieves a statistically significant result by excluding dropouts and those lost to follow up. The main impact of the analysis is to reduce the precision of the estimates by widening the confidence intervals. We continue to abide by the guidance of the Cochrane Collaboration convention, and present the outcomes on an intention to treat basis where possible, as they are currently displayed in the review.

Contributors

Neil Abbott

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 June 2019 | Amended | Minor edit to sources of support |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 1998 Review first published: Issue 2, 1998

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 March 2019 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Three new studies added, no changes to conclusions. |

| 7 December 2018 | New search has been performed | Searches updated 18 July 2018 and three new included trials added (Batra 2013; Dickson‐Spillmann 2013; Hasan 2014). Comparisons reorganized. Change of authorship: J Hartmann‐Boyce added. |

| 22 July 2010 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Change of authorship: N Abbott & A White removed; H McRobbie, N Walker, M Mehta added. |

| 22 July 2010 | New search has been performed | Updated with two new trials (Elkins 2006, Carmody 2008). Comparisons reorganised. No major change to conclusions. |

| 19 June 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 22 May 2005 | Amended | Response to Feedback included |

| 16 February 2005 | Amended | Response to Feedback included |

| 16 February 2005 | New search has been performed | Updated for 2005 Issue 2. Four references added to Excluded studies (Bastien 1983, Casmar 2003, Frank 1986, Richard 2002) |

| 5 August 2001 | New search has been performed | Updated for 2001 Issue 4. No new studies identified. |

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the important contributions of previous authors of this review: Neil Abbot initiated the review in 1998 and was first author until 2010; Edzard Ernst was an author until 2001; Adrian White was an author until 2010; Lindsay Stead and Monaz Mehta were authors until 2016. We also thank those authors who provided further information on included studies. We thank Sandra Wilcox and Lee Bromhead for their valuable feedback on the plain language summary.

JH‐B's time on this project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), via Cochrane Infrastructure and Cochrane Programme Grant funding to the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health and Social Care. JH‐B is also part‐funded by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC).

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Hypnotherapy versus attention‐matched behavioural interventions.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation at 6m+ follow up | 6 | 957 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.21 [0.91, 1.61] |

Comparison 2. Hypnotherapy versus brief behavioural interventions (not matched for contact time).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation at 6m+ follow up | 2 | 269 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.57, 1.69] |

Comparison 3. Hypnotherapy versus intensive behavioural interventions (not matched for contact time).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation at 6m+ follow up | 2 | 211 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.47, 1.82] |

Comparison 4. Hypnotherapy versus no treatment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation at 6m+ follow up | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 19.0 [1.18, 305.88] |

Comparison 5. Hypnotherapy versus rapid/focused smoking.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation at 6m+ follow up | 2 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.43, 2.33] |

| 1.1 Hypnotherapy alone vs Rapid/Focused smoking alone | 2 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.43, 2.33] |

Comparison 6. Hypnotherapy versus drug.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation at 6m + follow up | 2 | 197 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.68 [0.88, 3.20] |

| 1.1 Hypnotherapy vs NRT | 1 | 82 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.14 [0.98, 4.70] |

| 1.2 Hypnotherapy vs fenfluramine | 1 | 115 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.31, 3.33] |

Comparison 7. Hypnotherapy vs placebo drug.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation at 6m+ follow up | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Hypnotherapy alone vs Placebo drug alone | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 8. Hypnotherapy as an adjunct to other treatments.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation at 6m+ follow up | 5 | 224 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.10 [1.31, 3.35] |

| 1.1 Hypnotherapy + Brief attention/ advice vs Brief attention/ advice | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 9.0 [0.55, 147.95] |

| 1.2 Hypnotherapy + Psychological treatments vs Psychological treatments | 2 | 57 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.60 [1.79, 17.56] |

| 1.3 Hypnotherapy + Psychological treatments + Rapid smoking vs Psychological treatments + Rapid smoking | 1 | 44 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.10, 1.12] |

| 1.4 Hypnotherapy + NRT vs NRT alone | 1 | 79 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.00 [0.90, 4.49] |

| 1.5 Hypnotherapy + Psychological treatments vs Brief attention (relaxation)/ advice + Psychological treatments | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.0 [0.92, 17.40] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Barkley 1977.

| Methods | Site: USA, Bowling Green State University, Ohio. Study period: not stated. Recruitment: advertisements distributed in the university community. Sample size calculation: not mentioned. | |

| Participants | Number of participants: 36 smokers (12 in each group). Inclusion criteria: not stated. Exclusion criteria: those not able to meet demands of procedures including scheduling of treatment sessions, random assignment to groups, data collection, deposit requirements, etc. Overall demographics: primarily students and university affiliated persons, all of whom were young adults; 42% female. | |

| Interventions | a) Rapid smoking (based on a modified version of that reported by Keutzer 1968). b) Group hypnosis (hypnotic suggestions were the same as those reported by Hall and Crasilneck 1970). c) Attention placebo (watching films, receiving and discussing handouts on the topic, discussion of problems they might be experiencing in quitting smoking). All treatments: 7 x 1‐hour sessions over 2 weeks; first and last 15 mins spent discussing problems with quitting smoking, while 30 mins in the middle spent in treatment procedures. | |

| Outcomes | Definition of smoking cessation: point‐prevalence abstinence at 9‐month follow up. Adverse events: no information provided on how AE data were collected; number of participants in rapid smoking group experiencing vomiting was reported. | |

| Notes | Funding: partly supported by Department of Psychology, Bowling Green State University, fund. Author declaration of interest: not reported. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomized, method not stated, possibly stratified by gender |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details given |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Blinding not possible due to nature of intervention; self‐report only |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 7 participants missed at least one treatment session: (a) 0; (b) 4; (c) 3; not included in the original analysis, but included in our recalculations, following ITT analyses with missing assumed smoking. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes reported as described in the methods section |

Batra 2013.

| Methods | Setting: community, via University Hospital Tubingen and University of Hamburg, Germany. Study period: October 2010 to February 2012. Recruitment: participants recruited via advertisements in local media and university email campaigns. Sample size calculation: not described. | |

| Participants | Number of participants: 360 smokers (180 in each group). Inclusion criteria: current smokers prepared to stop smoking and who have smoked ≥10 CPD for the previous two years. Exclusion criteria: severe mental health disorder (e.g. psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, PTSD, current major depression, current alcohol or drug dependence); use of any tobacco products other than cigarettes; participation in any smoking cessation treatment within the past six months; current pregnancy or breastfeeding. Overall demographics: predominantly women (60%); mean age 43 years; mean CPD = 19; mean years as smoker = 26.5; mean FTND = 6.2. | |

| Interventions | a) Hypnotherapy ‐ trance‐induced and including: focusing on the desired internal and external condition, developing a positive self‐perception, reframing of smoking behaviour and relapses, and posthypnotic suggestions to connect cognitive and emotional sensations in trance with daily life and self‐hypnosis to strengthen imagination of living without cigarettes b) Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) ‐ including: psychoeducation, self‐monitoring of smoking behaviour, identification of smoking cues and smoking‐associated situations, functional analysis of smoking behaviour, motivational enhancement strategies, developing alternative behavioural options, self‐control and stimulus‐control strategies, reinforcement of abstinence, strategies to cope with smoking urges and withdrawal, relapse prevention strategies and strategies to cope with relapse. Both interventions were delivered by clinical psychologists as group sessions with 7 to 9 participants per group. Both interventions were delivered as one 90‐minute session per week for six weeks. Quit date was set to be between weeks 2 and 3 of treatment. Participants received EUR 10 for attending the 1‐ and 12‐month follow‐up sessions, and EUR 50 at the 12‐month follow‐up if they had completed all follow‐up assessments. |

|

| Outcomes | Definition of smoking cessation: Russell standard abstinence at 12 months (no more than 5 cigarettes and a CO reading < 10 ppm). Adverse events: no information provided on whether or not AE data were collected and whether any AEs occurred. | |

| Notes | Funding: not described. Author declaration of interest: not reported. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Participants were assigned to CBT or hypnotherapy via block randomization procedure |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Biochemically validated so differential misreport judged unlikely |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | If questionnaires were not returned, or CO measurement not available or > 9ppm, participants were considered smoking (but could have been successful quitters). CO measurement was available at 1 m and 12 Tm for 66.6 and 71.0% of participants, respectively. Around 20% of each group was LTFU by 52 weeks (CBT 78.8% and hypnotherapy 82.8% response at 12m follow up) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | A translation of the Methods document for the study, provided by the author, lists the data collection instruments to be used for the trial; some of the baseline variables collected, and the Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale‐Revised do not appear to be reported in the translation of the Results report. As the study is unpublished, the reason for this omission is unclear. |

Carmody 2008.

| Methods | Site: USA, San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Study period: September 2001‐December 2003. Recruitment: participants enrolled from the medical centre, referral practice to the medical centre is unknown. Sample size calculation: not mentioned. | |

| Participants | Number of participants: 286 smokers (hypnosis plus nicotine patch: 145; behaviour plus nicotine patch: 141). Inclusion criteria: current smokers interested in quitting (Stages of Change model, contemplation or action stage of quitting) and reported smoking ≥ 10 CPD during the pre‐enrolment week. Exclusion criteria: NRT contraindication. Overall demographics: predominantly unmarried, white, middle‐aged; smoked 20 CPD on average. | |

| Interventions | a) Hypnosis (training based on Spiegel (1994), Lynn et al. (1993), Green (1996, 1999) and Gorassini and Spanos (1986) + audiotape of hypnosis training to use daily at home).

b) Behavioural counselling based on social learning theory & Stages of Change model. Both groups received 2 x 60 mins face‐to‐face sessions + 3 x 20 mins follow‐up telephone counselling calls at weeks 3, 4 & 6 + 2 months supply of nicotine patch (initial dose: 21 mg or 14 mg). Duration of intervention: 2 months. |

|

| Outcomes | Definition of smoking cessation: point‐prevalence abstinence (defined as no smoking, not even a puff, for 7 days) at telephone follow‐up at 6 and 12 months. Adverse events: no information provided on whether or not AE data were collected and whether any AEs occurred. | |

| Notes | Funding: California Tobacco‐Related Diseases Research Program. The funding agency had no role in the conduct of the research or preparation of the manuscript. Author declaration of interest: not reported. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomized, using computer‐generated algorithm (SPSS, V.15) (information from author) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Subject numbers and the corresponding treatment assignments in sequentially numbered and sealed opaque envelopes. As each subject enrolled in the study, the study co‐ordinator supplied their counsellor with the envelope to open at the start of the first counselling session (information from author). |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The research associates who telephoned subjects for study follow‐up assessments were not blinded to their treatment condition, but biochemical confirmation of quitting was done by lab personnel blinded to treatment assignment. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | At 6 months:

a) Hypnosis: dropout: 4; withdrew: 1; died: 1; lost to follow‐up: 7

b) Behaviour: dropout:12, withdrew: 1; lost to follow‐up: 4

At 12 months (cumulative):

a) Hypnosis: dropout: 4; withdrew: 1; died: 4; lost to follow‐up: 11

b) Behaviour: dropout: 12; withdrew: 2; died: 1; lost to follow‐up: 5 Lost to follow‐up and withdrawn participants were included in the original analysis, with the imputation of being smokers at the endpoints, but 'dropout' patients were not included in the original analysis. The behaviour group 'dropout' (those who did not attend the second session of treatment) rate was 3 times that for the hypnosis group. We included all patients (i.e. 'dropout', withdrew, LTFU), except those who died, in our recalculations for ITT analyses (missing assumed smoking). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes reported as described in the methods section. |

Dickson‐Spillmann 2013.

| Methods | Setting: Swiss Institute for Research in Public Health and Addictions, which is associated with the University of Zurich, Switzerland. Study period: April 2011 to February 2012. Recruitment: through advertisements in online and print newspapers. Sample size calculation: described for initial planned simple RCT and then redone as authors realized the study is a cluster‐RCT. |

|

| Participants | Number of participants: 223 smokers (hypnosis: 116; relaxation: 107). Inclusion criteria: current smokers prepared to stop smoking; smoking ≥ 5 cigarettes per day; aged 18 to 65 years; not using other cessation aids; understand and speak German; no history of psychotic disorders; not be intoxicated before or during the intervention. Exclusion criteria: using other cessation aids; history of psychotic disorders; intoxicated before or during the intervention. Overall demographics: women (47%); mean age = 37.5 (SD 11.8); Swiss (86.1%) years; mean FTND = 4.7. | |

| Interventions | a) Hypnosis b) Relaxation Both groups received a 40‐minute psychoeducation session before their intervention, a 20‐minute debriefing after the intervention, and a CD for use at home. Both interventions comprised a single 40‐minute session of group treatment. Participants were required to pay CHF 40 to participate in the study. |

|

| Outcomes | Definition of smoking cessation: biochemically validated (saliva cotinine < 5 ng/mL undertaken by post) 30‐day point prevalence of smoking abstinence at a 6‐month follow up. Adverse events: collected at 2‐week telephone follow‐up interview and at 6‐month postal follow‐up questionnaire. | |

| Notes | Funding: Swiss Tobacco Prevention Fund. Author declaration of interest: "The authors declare that they have no competing interests". The study was initially planned as an individually‐randomized RCT but analysis was changed to that suitable for a cluster‐RCT when it was realized that the unit of recruitment was clusters (e.g. groups of work colleagues). Cluster randomization was accounted for in the analysis. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Random sequence of 20 sessions generated using an online programme with ratio of 1:1 for number of sessions per intervention; one additional last session was randomly allocated by the same programme. Does not state if a block size was used or not |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Therapist blinded until delivery of intervention; therapist was informed by text immediately prior as to which intervention should be delivered. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Biochemically validated so differential misreport judged unlikely |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Those with absent saliva sample (n = 1), and those with saliva cotinine higher than usual for occasional smokers (n = 3), were classed as smokers. At 6 months, LTFU for the hypnosis and relaxation groups was 14.7% and 17.1%, respectively. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Primary outcome variable reported and information provided on numbers without biochemical validation. However, 2‐week, but not 6‐month, AE data reported and reason for this omission is unclear. |

Elkins 2006.

| Methods | Site: USA; most authors worked for Scott and White Memorial Hospital and Clinic, Temple, Texas. Study period: not stated. Recruitment: physician referral and advertisements. Sample size calculation: not mentioned (pilot study). | |

| Participants | Number of participants: 20 smokers (number in group not specified, no response from author. Assumed 10/group in analysis). Inclusion criteria: at least 18 years, smoking ≥ 10 CPD, interested in quitting smoking in the next 30 days, able to attend weekly sessions, spoke English. Exclusion criteria: regular use of any non‐cigarette tobacco product, reported current abuse of alcohol or psychoactive drugs, current use of any other smoking‐cessation treatments, any reported history of borderline personality disorder, or currently using hypnotherapy for any reason. Overall demographics: average age early to mid‐40s, majority female, Caucasian, married, high school education; > 20 CPD; Fagerstrom score of slightly > 10. | |

| Interventions | a) Intensive hypnotherapy ‐ 8 x 1 hour sessions of hypnotherapy (9 steps hypnotic induction) plus self‐hypnosis tape for daily practice. b) Waiting‐list control. Both groups: National Cancer institute self‐help materials, encouraged to set TQD, 3 x 5 to 10 mins supportive phone calls at weeks 2, 4 & 5. Duration of intervention: approximately 2 months. | |

| Outcomes | Definition of smoking cessation: 7‐day point‐prevalence abstinence at week 26. Adverse events: no information provided on whether or not AE data were collected and whether any AEs occurred. | |

| Notes | Funding: not stated. Author declaration of interest: not reported. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomized, method not stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details given |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinding not possible due to nature of intervention, but cessation was biochemically verified: CO 8 ppm or less at each visit. If CO value greater than 8 ppm, saliva cotinine had to be less than 20 ng/mL. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Authors stated they conducted an ITT analysis with participants unavailable for assessment counted as non‐abstainers; no data were provided on dropout rates so it is not known if there was differential dropout between groups. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes reported as described in the methods section. |

Fee 1977.

| Methods | Site: UK, an anti‐smoking clinic in Tayside, Scotland. Study period: 1970 to 1972. Recruitment: personal application or hospital or GP referral. Sample size calculation: not mentioned. | |

| Participants | Number of participants: 232 smokers (hypnosis: 57; aversion: 60; fenfluramine: 58; placebo: 57). Inclusion criteria: not stated. Exclusion criteria: not stated. Overall demographics: no information reported. | |

| Interventions | a) Individual hypnosis b) Aversion therapy (covert sensitisation) c) Fenfluramine d) Placebo There was a standard 9‐week course treatment for all intervention groups. Number and duration of sessions not stated; treatment method details not provided. | |