Abstract

Background

Liver cancer is a common malignancy and a significant public health problem worldwide, but diagnosis and prognostic evaluation remain challenging for clinicians. Metabolic reprogramming is a hallmark of cancer, and we therefore examined the diagnostic and prognostic value of a metabolic enzyme, phosphoglucomutase-like protein 5 (PGM5), in liver cancer.

Methods

All data were from The Cancer Genome Atlas database. R and related statistical packages were used for data analysis. Hepatic PGM5 expression was determined in different groups, and the chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test were used to determine the significance of differences. The pROC package was used to determine receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, the survival package was used to for survival analysis and development of a Cox multivariable model, and the ggplot2 package was used for data visualization.

Results

PGM5 expression was significantly lower in cancerous than adjacent normal liver tissues, and had modest diagnostic value based on ROC analysis and calculations of area under the curve (AUC). Hepatic PGM5 expression had positive associations with male sex and survival, but negative associations with advanced histologic type, advanced histologic grade, advanced stage, and advanced T classification. Patents with low PGM5 levels had poorer overall survival and relapse-free survival. PGM5 was independently associated with patient prognosis.

Conclusion

PGM5 has potential use as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for liver cancer.

Keywords: Liver cancer, Diagnosis, Prognosis, Data mining, PGM5

Introduction

Liver cancer is one of the most common malignancies, and patients typically experience poor prognoses (Llovet et al., 2016). According to global cancer statistics for 2018 (Bray et al., 2018), liver cancer is the sixth most common cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths, with about 841,000 new cases and 782,000 deaths each year. Although there have been improvements in surgical resection, transplantation, radiofrequency ablation, and chemical embolization, and therapy with sorafenib (an inhibitor of multiple tyrosine kinases) is now available, patient prognosis has only modestly improved in recent years. Histological parameters, including histological subtype and grade, together with TNM classification, are mainly used for patient evaluation and prediction of prognosis. However, accurate prediction of prognosis remains challenging for clinicians. There is an urgent need for novel biomarkers to improve diagnostic accuracy and better predict prognosis.

Metabolic reprogramming is a hallmark of all cancers. Phosphoglucomutase-like protein 5 (PGM5, also called aciculin), which metabolizes glucose-1-phosphate into glucose-6-phosphate, may play an important role in liver cancer. In the past ten years, studies of PGM5 have focused on its role in muscle tissues, and reported its associations with the cytoskeletal proteins dystrophin and utrophin (Belkin & Burridge, 1994; Belkin & Burridge, 1995a; Belkin & Burridge, 1995b). Several additional studies identified its chromosome fusion site and relationship with telomeres (Edwards et al., 1995; Fan et al., 2002). Recent studies used cell transformation to investigate its expression and pathogenic role in bladder and colorectal cancers (Li et al., 2018; Uzozie et al., 2017).

However, no studies have yet reported the clinical significance, diagnostic value, and prognostic value of PGM5 in patients with liver cancer. We examined the hepatic expression of PGM5 in patients with liver cancer, determined its association with clinical parameters, calculated its diagnostic value using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, and performed survival analysis and Cox modeling to evaluate its effect on prognosis.

Materials & Methods

Data mining of a public database

Data mining was used to obtain raw data on patients with liver hepatocellular carcinoma. In particular, RNAseq data of PGM5 and clinical data were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas database using UCSC Xena (https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/?cohort=TCGA%20Liver%20Cancer%20(LIHC)&removeHub=https%3A%2F%2Fxena.treehouse.gi.ucsc.edu%3A443%22). There was no need for ethical approval because all data were publicly available.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses produce were performed using R (version 3.5.2) and related packages (R Development Core Team, 2018). PGM5 expression data are presented in boxplots. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test (also known as Mann–Whitney non-parametric test) was used to compare two groups, and the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare three or more groups. ROC was drawn using the pROC package to evaluate the diagnostic value of PGM5 by calculation of the AUC (Robin et al., 2011). Patients were divided into a high expression group and a low expression group using the threshold PGM5 level identified from the ROC curve. The chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test were used to assess the significance of associations between PGM5 level and clinical parameters. Survival analysis and the Cox model were implemented using the survival package in R to determine the prognostic value of PGM5 overall, and in different subgroups (Therneau & Grambsch, 2000), with calculations of hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Data were plotted using the ggplot2 package in R (Wickham, 2011).

Results

Characteristics of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma

The Cancer Genome Atlas database provided the characteristics of 373 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, including age, sex, cancer stage, histologic grade, histological type, TNM classification, presence of residual tumor, and vital status (Table 1).

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the liver cancer patients.

| Characteristics | Number of patients(%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| <55 | 117(31.45) |

| ≥55 | 255(68.55) |

| Gender | |

| FEMALE | 121(32.44) |

| MALE | 252(67.56) |

| histological_type | |

| Fibrolamellar Carcinoma | 3(0.8) |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | 363(97.32) |

| Hepatocholangiocarcinoma (Mixed) | 7(1.88) |

| histologic_grade | |

| NA | 5(1.34) |

| G1 | 55(14.75) |

| G2 | 178(47.72) |

| G3 | 123(32.98) |

| G4 | 12(3.22) |

| Stage | |

| NA | 24(6.43) |

| I | 172(46.11) |

| II | 87(23.32) |

| III | 85(22.79) |

| IV | 5(1.34) |

| T_classification | |

| NA | 2(0.54) |

| T1 | 182(48.79) |

| T2 | 95(25.47) |

| T3 | 80(21.45) |

| T4 | 13(3.49) |

| TX | 1(0.27) |

| N_classification | |

| NA | 1(0.27) |

| N0 | 253(67.83) |

| N1 | 4(1.07) |

| NX | 115(30.83) |

| M_classification | |

| M0 | 267(71.58) |

| M1 | 4(1.07) |

| MX | 102(27.35) |

| radiation_therapy | |

| NA | 25(6.7) |

| NO | 340(91.15) |

| YES | 8(2.14) |

| residual_tumor | |

| NA | 7(1.88) |

| R0 | 326(87.4) |

| R1 | 17(4.56) |

| R2 | 1(0.27) |

| RX | 22(5.9) |

| Vital_status | |

| DECEASED | 130(34.85) |

| LIVING | 243(65.15) |

| Relapse | |

| NO | 179(55.94) |

| YES | 141(44.06) |

| PGM5 | |

| High | 165(44.24) |

| Low | 208(55.76) |

Lower hepatic PGM5 expression in cancerous than normal tissues

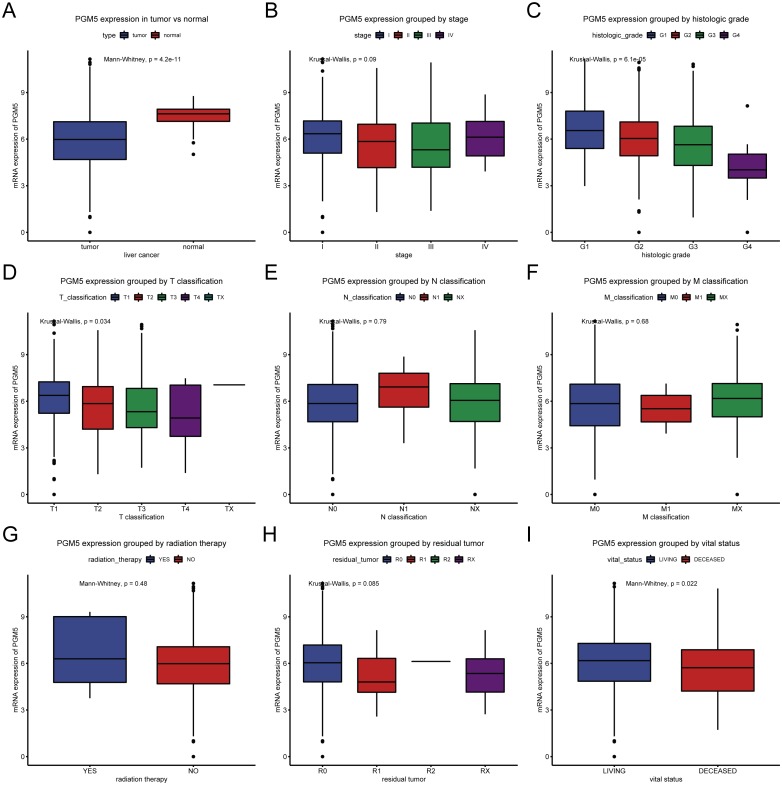

We determined the association of PGM5 expression with different tissue characteristics (Fig. 1). The results show that PGM5 expression was lower in tissues with liver cancer (n = 373) than in adjacent normal liver tissues (n = 50; P = 4.2 ×10−11). In addition, PGM5 expression had inverse correlations with advanced histologic grade (P = 6.1 × 10−5) and advanced T classification (P = 0.034), and a positive correlation with survival (P = 0.022).

Figure 1. Expression of PGM5 in liver cancer.

Expression of PGM5 in cancerous vs. adjacent normal liver tissues (A), and according to clinical stage (B), histologic grade (C), TNM classification (D–F), receipt of radiation therapy (G), presence of residual tumor (H), and survival (I). Each box plot shows the median (center line), upper and lower quartiles (box), 95% confidence intervals (vertical lines), and outliers (points).

Hepatic PGM5 expression has diagnostic value in liver cancer

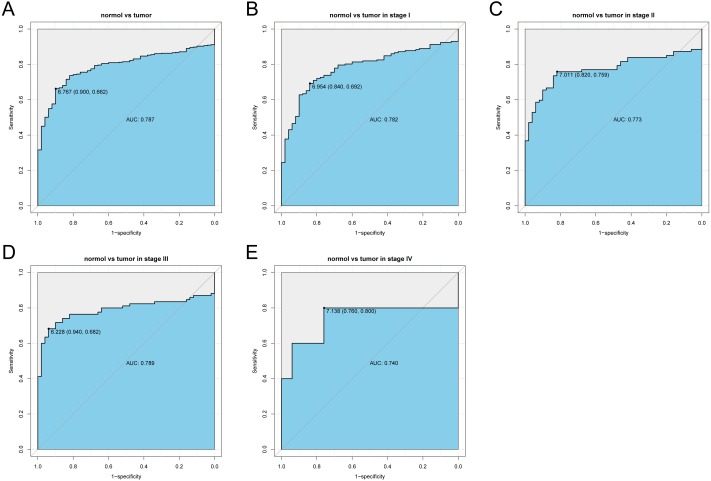

We analyzed the PGM5 expression data in cancerous liver tissues using ROC analysis for all patients, and for patients with different stages of cancer (Fig. 2). The results show that PGM5 expression had a modest diagnostic value for patients overall (AUC = 0.787) and for patients with different stages of cancer (AUCStageI = 0.782; AUCStageII = 0.773, AUCStageIII = 0.789; AUCStageIV = 0.740).

Figure 2. Receiver operating characteristic analysis of hepatic PGM5 expression.

Receiver operating characteristic analysis of hepatic PGM5 expression in (A) normal vs. cancerous tissues overall (A), normal vs. stage I cancerous tissues (B), normal vs. stage II cancerous tissues (C), normal vs. stage III cancerous tissues (D), and normal vs. stage IV cancerous tissues (E).

Hepatic PGM5 expression correlates with several clinical parameters

We evaluated the association of PGM5 expression with clinical parameters by dividing patients into a high expression group and a low expression group according to the threshold value identified from the ROC curve. Analysis of these data using a chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test (Table 2) indicated that PGM5 expression was positively associated with male sex (P = 0.044) and survival (P = 0.009), but inversely associated with advanced histologic type (P = 0.045), advanced histologic grade (P = 0.044), advanced stage (P = 0.008), and advanced T classification (P = 0.001).

Table 2. Relationship between the clinical features and PGM5 expression in liver cancer patients.

| Clinical characteristics | Variable | No. of patients | PGM5 expression | χ2 | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | % | Low | % | |||||

| Age | <55 | 117 | 53 | (32.12) | 64 | (30.92) | 0.019 | 0.892 |

| ≥55 | 255 | 112 | (67.88) | 143 | (69.08) | |||

| Gender | FEMALE | 121 | 44 | (26.67) | 77 | (37.02) | 4.040 | 0.044 |

| MALE | 252 | 121 | (73.33) | 131 | (62.98) | |||

| Histological type | Fibrolamellar Carcinoma | 3 | 3 | (1.82) | 0 | (0) | 9.357 | 0.005 |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | 363 | 162 | (98.18) | 201 | (96.63) | |||

| Hepatocholangiocarcinoma (Mixed) | 7 | 0 | (0) | 7 | (3.37) | |||

| Histologic grade | G1 | 55 | 32 | (19.63) | 23 | (11.22) | 12.826 | 0.004 |

| G2 | 178 | 83 | (50.92) | 95 | (46.34) | |||

| G3 | 123 | 47 | (28.83) | 76 | (37.07) | |||

| G4 | 12 | 1 | (0.61) | 11 | (5.37) | |||

| Stage | I | 172 | 91 | (58.71) | 81 | (41.75) | 11.191 | 0.008 |

| II | 87 | 35 | (22.58) | 52 | (26.8) | |||

| III | 85 | 27 | (17.42) | 58 | (29.9) | |||

| IV | 5 | 2 | (1.29) | 3 | (1.55) | |||

| T classification | T1 | 182 | 98 | (60.12) | 84 | (40.38) | 17.897 | 0.001 |

| T2 | 95 | 37 | (22.7) | 58 | (27.88) | |||

| T3 | 80 | 23 | (14.11) | 57 | (27.4) | |||

| T4 | 13 | 4 | (2.45) | 9 | (4.33) | |||

| TX | 1 | 1 | (0.61) | 0 | (0) | |||

| N classification | N0 | 253 | 110 | (67.07) | 143 | (68.75) | 1.592 | 0.451 |

| N1 | 4 | 3 | (1.83) | 1 | (0.48) | |||

| NX | 115 | 51 | (31.1) | 64 | (30.77) | |||

| M classification | M0 | 267 | 118 | (71.52) | 149 | (71.63) | 0.631 | 0.809 |

| M1 | 4 | 1 | (0.61) | 3 | (1.44) | |||

| MX | 102 | 46 | (27.88) | 56 | (26.92) | |||

| Radiation therapy | NO | 340 | 150 | (97.4) | 190 | (97.94) | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| YES | 8 | 4 | (2.6) | 4 | (2.06) | |||

| Residual tumor | R0 | 326 | 151 | (93.21) | 175 | (85.78) | 5.447 | 0.115 |

| R1 | 17 | 5 | (3.09) | 12 | (5.88) | |||

| R2 | 1 | 0 | (0) | 1 | (0.49) | |||

| RX | 22 | 6 | (3.7) | 16 | (7.84) | |||

| Vital status | DECEASED | 130 | 45 | (27.27) | 85 | (40.87) | 6.900 | 0.009 |

| LIVING | 243 | 120 | (72.73) | 123 | (59.13) | |||

Notes.

Bold values of P ≤ 0.05 indicate statistically significant.

Hepatic PGM5 expression is an independent prognostic factor

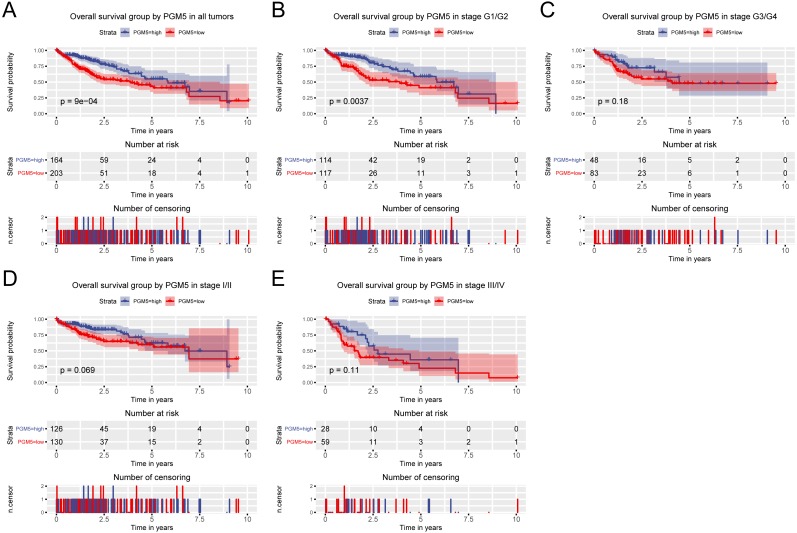

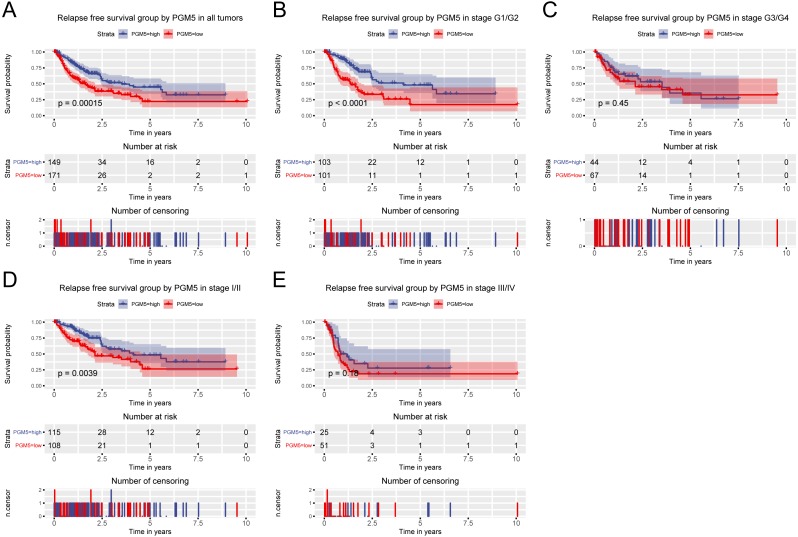

Because high PGM5 expression correlated with improved survival, we also examined the role of PGM5 expression in prediction of patient prognosis. The results show that patients with lower PGM5 expression had a shorter overall survival (OS; Fig. 3, P = 9 × 10−4) and relapse-free survival (RFS; Fig. 4, P = 0.00015). Subgroup analysis indicated that PGM5 expression had significant prognostic value for OS in patients with stage I/II cancer (P = 0.0037) and for RFS in patients with stage I/II cancer (P < 0.0001) and grade G1/G2 cancer (P = 0.0039).

Figure 3. Relationship of hepatic PGM5 expression with overall survival.

Relationship of hepatic PGM5 expression with overall survival in all patients (A), patients with histological grade G1/G2 (B), patients with histological grade G3/G4 (C), patients with clinical stage I/II (D), and patients with clinical stage III/IV (E).

Figure 4. Relationship of hepatic PGM5 expression with relapse-free survival.

Relationship of hepatic PGM5 expression with relapse-free survival in all patients (A), patients with histological grade G1/G2 (B), patients with histological grade G3/G4 (C), patients with clinical stage I/II (D), and patients with clinical stage III/IV (E).

We developed a Cox model to evaluate the effect of PGM5 expression on OS and RFS (Tables 3 and 4). The univariate Cox model indicated the variables potentially associated with PGM5 expression were stage, histologic grade, and T classification. The multivariate Cox model identified PGM5 expression as an independent prognostic indicator of OS (HR = 1.51, 95% CI [1.04–2.18], P = 0.029) and RFS (HR = 1.67, 95% CI [1.18–2.36], P = 0.004).

Table 3. Univariate analysis and multivariate analysis of liver cancer patients’ overall survival.

| Parameters | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | 95% CI (lower∼ upper) | P value | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI (lower-upper) | P value | |

| Age | 1.00 | 0.69–1.45 | 0.997 | |||

| Gender | 0.80 | 0.56–1.14 | 0.220 | |||

| Histological type | 0.99 | 0.27–3.66 | 0.986 | |||

| Histologic grade | 1.04 | 0.84–1.3 | 0.698 | |||

| Stage | 1.38 | 1.15–1.66 | 0.001 | 0.87 | 0.7–1.09 | 0.220 |

| T classification | 1.66 | 1.39–1.99 | 0.000 | 1.77 | 1.39–2.24 | 0.000 |

| N classification | 0.73 | 0.51–1.05 | 0.086 | |||

| M classification | 0.72 | 0.49–1.04 | 0.077 | |||

| Radiation therapy | 0.51 | 0.26–1.03 | 0.060 | |||

| Residual tumor | 1.42 | 1.13–1.8 | 0.003 | 1.39 | 1.09–1.78 | 0.008 |

| PGM5 | 1.83 | 1.27–2.63 | 0.001 | 1.51 | 1.04–2.18 | 0.029 |

Table 4. Univariate analysis and multivariate analysis of liver cancer patients’ relapse-free survival.

| Parameters | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | 95% CI (lower∼ upper) | P value | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI (lower-upper) | P value | |

| Age | 0.90 | 0.63–1.28 | 0.550 | |||

| Gender | 0.99 | 0.7–1.41 | 0.966 | |||

| Histological type | 2.02 | 0.66–6.24 | 0.220 | |||

| Histologic grade | 0.98 | 0.8–1.21 | 0.883 | |||

| Stage | 1.66 | 1.38–1.99 | 0.000 | 1.14 | 0.88–1.48 | 0.326 |

| T classification | 1.78 | 1.49–2.12 | 0.000 | 1.57 | 1.19–2.05 | 0.001 |

| N classification | 0.97 | 0.67–1.4 | 0.874 | |||

| M classification | 1.17 | 0.79–1.74 | 0.432 | |||

| Radiation therapy | 0.74 | 0.26–2.16 | 0.584 | |||

| Residual tumor | 1.28 | 1.01–1.61 | 0.042 | 1.32 | 1.04–1.67 | 0.023 |

| PGM5 | 1.92 | 1.36–2.7 | 0.000 | 1.67 | 1.18–2.36 | 0.004 |

Discussion

Our team have been engaged in exploring the novel cancer biomarks for a long time (Jiao et al., 2018; Jiao et al., 2019a; Jiao et al., 2019b). The present study indicated that PGM5 expression was lower in cancerous than adjacent normal liver tissues. Hepatic PGM5 expression was also positively associated with male sex and survival, and negatively associated with advanced histologic type, histologic grade, clinical stage, and T classification. We also found that hepatic PGM5 expression had significant value as a diagnostic indicator of liver cancer and that patients with low hepatic PGM5 expression had poorer prognosis, in terms of OS and RFS. The results of our Cox model analysis indicated low hepatic PGM5 expression was an independent indicator of poor prognosis.

PGM5 (initially named aciculin) is a cytoskeletal protein present in smooth muscle tissues (Belkin & Burridge, 1994). Initial studies reported changes of PGM5 expression during muscledifferentiation, in that there is upregulation during muscle development, and that this protein is a useful marker of the contractile/differentiated smooth muscle phenotype (Belkin & Burridge, 1994; Moiseeva & Critchley, 1997). However, little is known about the expression of PGM5 during cancer pathogenesis. The present study indicated that PGM5 had lower expression in cancerous liver tissues than adjacent normal tissues, similar to the results of a previous study of colorectal cancer (Uzozie et al., 2017). Furthermore, we determined that hepatic PGM5 expression had a modest diagnostic value for liver cancer overall and for each of the four stages of liver cancer, suggesting it has potential use as a novel diagnostic biomarker.

Low hepatic PGM5 expression is associated with poor prognosis in patients with liver cancer. Previous studies found that PGM5 functions in multiple cell–matrix adherens junctions in association with dystrophin and utrophin, and that it interacts with filamin C and Xin during myofibril assembly, remodeling, and maintenance (Belkin & Burridge, 1995a; Belkin & Burridge, 1995b; Molt et al., 2014; Wakayama et al., 2000). Its chromosome fusion site is close to the telomere, and is related to the rearrangement of subtelomeric and pericentromeric regions (Fan et al., 2002; Wong et al., 2004). These previous findings suggest this protein has a role in cell–matrix adherens junctions and the regulation of telomeres during cancer progression, although no previous study has yet directly examined the specific function of PGM5 during the pathogenesis of cancer. Our study of patients with liver cancer indicated that hepatic PGM5 expression was positively associated with male sex and survival, and negatively associated with advanced histologic type, histologic grade, stage, and T classification. Our survival analysis indicated that low hepatic PGM5 expression was associated with poor prognosis, and was an independent prognostic factor for poor OS and RFS. These results indicate that PGM5 has potential as a prognostic biomarker, as well as a diagnostic marker, for liver cancer.

This study and several previous studies suggest that PGM5 has a role in the pathogenesis of several cancers, and has potential value as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for liver cancer. However, this study is based on data mining of a single public database, so our findings require verification in different populations. Our future studies will examine the role of PGM5 in liver cancer of different populations and will also examine its molecular function using in vivo and in vitro experiments.

Conclusions

In summary, we found that PGM5 expression was lower in cancerous than adjacent normal liver tissues, and was positively associated with male sex and survival, and negatively associated with advanced histologic type, histologic grade, stage, and T classification. In addition, patients with low expression of hepatic PGM5 had poorer OS and RFS. Our Cox model results indicated that hepatic PGM5 expression was an independent prognostic factor. However, our results are based on data mining of a selected group of patients from a public database, so verification is required for additional populations.

Supplemental Information

Abbreviations

- 95% CI

95% confidence interval

- AUC

area under curve

- HR

hazard ratio

- OS

overall survival

- PGM5

phosphoglucomutase-like protein 5

- RFS

relapse-free survival

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

Funding Statement

The authors received no funding for this work.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare there are no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Yan Jiao conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Yanqing Li performed the experiments, analyzed the data, approved the final draft.

Peiqiang Jiang contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, approved the final draft.

Wei Han prepared figures and/or tables, approved the final draft.

Yahui Liu conceived and designed the experiments, approved the final draft.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data are available as Supplemental Files. The data was collected from TCGA (https://cancergenome.nih.gov/) and UCSC Xena (https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/).

References

- Belkin & Burridge (1994).Belkin AM, Burridge K. Expression and localization of the phosphoglucomutase-related cytoskeletal protein, aciculin, in skeletal muscle. Journal of Cell Science. 1994;107(Pt 7):1993–2003. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.7.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkin & Burridge (1995a).Belkin AM, Burridge K. Association of aciculin with dystrophin and utrophin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995a;270:6328–6337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.6328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkin & Burridge (1995b).Belkin AM, Burridge K. Localization of utrophin and aciculin at sites of cell–matrix and cell–cell adhesion in cultured cells. Experimental Cell Research. 1995b;221(1):132–140. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray et al. (2018).Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards et al. (1995).Edwards YH, Putt W, Fox M, Ives JH. A novel human phosphoglucomutase (PGM5) maps to the centromeric region of chromosome 9. Genomics. 1995;30(2):350–353. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.9866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan et al. (2002).Fan Y, Newman T, Linardopoulou E, Trask BJ. Gene content and function of the ancestral chromosome fusion site in human chromosome 2q13-2q14.1 and paralogous regions. Genome Research. 2002;12:1663–1672. doi: 10.1101/gr.338402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao et al. (2018).Jiao Y, Fu Z, Li Y, Meng L, Liu Y. High EIF2B5 mRNA expression and its prognostic significance in liver cancer: a study based on the TCGA and GEO database. Cancer Management and Research. 2018;10:6003–6014. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S185459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao et al. (2019a).Jiao Y, Fu Z, Li Y, Zhang W, Liu Y. Aberrant FAM64A mRNA expression is an independent predictor of poor survival in pancreatic cancer. PLOS ONE. 2019a;14(1):e0211291. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao et al. (2019b).Jiao Y, Li Y, Lu Z, Liu Y. High trophinin-associated protein expression is an independent predictor of poor survival in liver cancer. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2019b;64:137–143. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5315-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li et al. (2018).Li M, Liu Y, Zhang X, Liu J, Wang P. Transcriptomic analysis of high-throughput sequencing about circRNA, lncRNA and mRNA in bladder cancer. Gene. 2018;677:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llovet et al. (2016).Llovet JM, Zucman-Rossi J, Pikarsky E, Sangro B, Schwartz M, Sherman M, Gores G. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2016;2:16018. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moiseeva & Critchley (1997).Moiseeva EP, Critchley DR. Characterisation of the promoter which regulates expression of a phosphoglucomutase-related protein, a component of the dystrophin/utrophin cytoskeleton predominantly expressed in smooth muscle. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1997;248:634–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molt et al. (2014).Molt S, Buhrdel JB, Yakovlev S, Schein P, Orfanos Z, Kirfel G, Winter L, Wiche G, Van der Ven PF, Rottbauer W, Just S, Belkin AM, Furst DO. Aciculin interacts with filamin C and Xin and is essential for myofibril assembly, remodeling and maintenance. Journal of Cell Science. 2014;127:3578–3592. doi: 10.1242/jcs.152157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin et al. (2011).Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N, Lisacek F, Sanchez JC, Muller M. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team (2018).R Development Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Therneau & Grambsch (2000).Therneau TM, Grambsch PMJPotASA. Modeling survival data: extending the cox model. Technometrics. 2000;97:353–354. [Google Scholar]

- Uzozie et al. (2017).Uzozie AC, Selevsek N, Wahlander A, Nanni P, Grossmann J, Weber A, Buffoli F, Marra G. Targeted proteomics for multiplexed verification of markers of colorectal tumorigenesis. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2017;16:407–427. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M116.062273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakayama et al. (2000).Wakayama Y, Inoue M, Kojima H, Murahashi M, Shibuya S, Yamashita S, Oniki H. Aciculin and its relation to dystrophin: immunocytochemical studies in human normal and Duchenne dystrophy quadriceps muscles. Acta Neuropathologica. 2000;99:654–662. doi: 10.1007/s004010051176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham (2011).Wickham HJ. Ggplot2:elegant graphics for data analysis, vol. 174. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2011. pp. 245–246. [Google Scholar]

- Wong et al. (2004).Wong A, Vallender EJ, Heretis K, Ilkin Y, Lahn BT, Martin CL, Ledbetter DH. Diverse fates of paralogs following segmental duplication of telomeric genes. Genomics. 2004;84:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data are available as Supplemental Files. The data was collected from TCGA (https://cancergenome.nih.gov/) and UCSC Xena (https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/).