Abstract

Background

This study was designed to evaluate the effects of a 24-month period of moderate exercise on serum lipids in menopausal women.

Methods

The subjects (40–60 y) were randomly divided into an exercise group (n = 14) and a control group (n = 13). The women in the exercise group were asked to participate in a 90-minute physical education class once a week and to record their daily steps as measured by a pedometer for 24 months.

Results

Mean of daily steps was significantly higher in the exercise group from about 6,800 to over 8,500 steps (P < 0.01). In the control group, the number of daily steps ranged from 5,700 to 6,800 steps throughout the follow-up period. A significant interaction between the exercise group and the control group in the changes og total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLC) and TC : HDLC ratio could be observed (P < 0.05). By multiple regression analysis, the number of daily steps was related to HDLC and TC : HDLC levels after 24 months, and the changes in TC and HDLC concentrations.

Conclusions

These results suggest that daily exercise as well as increasing the number of daily steps can improve the profile of serum lipids.

Background

It is known that lipid metabolism rapidly deteriorates in women when they reach menopause. In addition, it has been reported that the morbidity due to hyperlipidemia and coronary heart disease rises in women of menopausal age. This is mostly based on the decrease in estrogen, which has the action of controlling LDL production, advancing of HDL production and antioxidation [1,2]. In Japan, Western dietary habits, especially increased fat intake and decreased carbohydrate intake, are becoming one of the causes of the deterioration of the serum lipids [3]. This fact suggests that preventing the deterioration of serum lipids during menopause is very important.

Exercise is one of the methods to prevent the deterioration of serum lipids. It has been clarified that exercise can bring the serum lipids to an acceptable range [4-8]. However, with respect to the sex difference, the effect of exercise is more difficult to be detected in women compared with men [6,9,10]. Also, Motoyama et al.[6] reported that in elderly persons long-term low intensity aerobic training improved the profile of serum lipid and lipoprotein concentrations, while detraining returned the profile to that of the pre-training levels. In elderly women, it has also been demonstrated that the serum lipid levels of a person who continues exercise arc clearly different from those of a person who does not [11]. Hence, it is essential for a woman in her menopausal age to continue a long-term exercise schedule to improve her serum lipid profile.

Dose-response improvement in performance capacity after exercise training has been the subject of a number of studies [12,13]. On the basis of such scientific reports, conclusions were taken as the positive effects of endurance of high-intensity exercise training on increasing maximum oxygen consumption. For instance, according to the guidelines of the American College of Sports Medicine [14], the conditions for effective exercise are: 20–60 minuets of moderate- to high-intensity endurance exercise (50–85% of maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) performed three or more times per week. However, it has been reported recently that intermittent bouts of physical activity, as short as 8 to 10 min, totaling 30 min or more on most days provide beneficial health and fitness effects [15]. In addition, it is recommended that the intermittent activity is not necessarily exercising training [16,17]. For example, walking up the stairs instead of taking the elevator, waking instead of driving short distance, gardening, housework, and so on. Therefore, it can be considered that the amount of activity is more important than the specific mode of activity performed. It is reported that the current low-participation rate of general population in sports activities may be due, in part, to the misperception of many people that to reap health benefits they must engage in vigorous, continuous exercise [15]. This view is of practical importance and is consistent with health recommendations for menopausal women, for whom the issues of moderate and short bouts of physical activity are of greater interest.

In the present study, in order to ensure that the subjects would continue their exercise program, only the increase in the number of their daily steps was requested for submission, and the subjects were asked but not obliged, to participate in the physical education class once a week. This 24-month follow-up study examined whether low intensity physical activity that seems to produce endurance gains is similarly effective in improving the blood lipid in menopausal women.

Methods

Subjects

A written explanation of the experimental procedures (physical education class) and potential risks was presented to each subject and informed consent was obtained.

The subjects were forty-eight menopausal women (age: 40–60 years) who participated in this study. None of them had engaged in any regular exercise program prior to this study. Then they were randomly divided into two groups, one consisting of 32 persons who consented to participate in the physical education class (exercise group), and the other consisting of 16 persons who did not (control group). As mentioned before, the subjects were not obliged to participate in the physical education class, hence we anticipated that some of them might discontinue attending the program over the 24-month follow-up investigation. On the basis of this assumption, the number of subjects in the exercise group was two times of that in the control group. The 32 subjects in the exercise group fell to 20 persons over the 24-month period, and 14 of them were selected to comprise the final exercise group based on the following criteria: (a) ages of < 55 years (48.6 ± 4.2 years), (b) no special diseases and medication, and (c) complete information available for each individual. Among the 16 subjects in the control group, 13 of them were selected to serve as the final control group based on the same criteria (48.0 ± 3.6 years). The subjects in both groups were asked to provide samples for blood examinations for 24-month. The profiles of the subject are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the subjects in the exercise group and the control group

| Exercise (N = 14) | Control (N = 13) | |||

| Start | 24 M | Start | 24 M | |

| Age (year)a | 48.6 ± 4.2 | 48.0 ± 3.6 | ||

| Weight (kg)a | 54.1 ± 4.3 | 53.2 ± 3.9 | 55.2 ± 5.3 | 55.6 ± 4.2 |

| BM1a | 22.3 ± 1.6 | 22.0 ± 1.8 | 22.6 ± 1.9 | 22.7 ± 1.4 |

| Menopausal statusb | ||||

| Postmenopause | 5 | 9 | 4 | 6 |

| Menopause | 6 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Premenopause | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

aValues are means ± SD. bValues are number of the subjects. BMI: body mass index, Start: the start of this study, 24 M: after 24 months

The conditions of menstruation were defined as follows. Postmenopausal women: those who have no menstruation over half a year, and whose balance of follicle-stimulating hormone and estradiol 2 shows the pattern characteristic of postmenopause. Menopausal women: those whose menstrual cycle is irregular, yet have menstruation within the half year, and whose pattern of hormone balance is not characteristic of postmenopause. Premenopausal women: those whose menstrual cycle is regular.

An outline of the physical education class for menopausal women

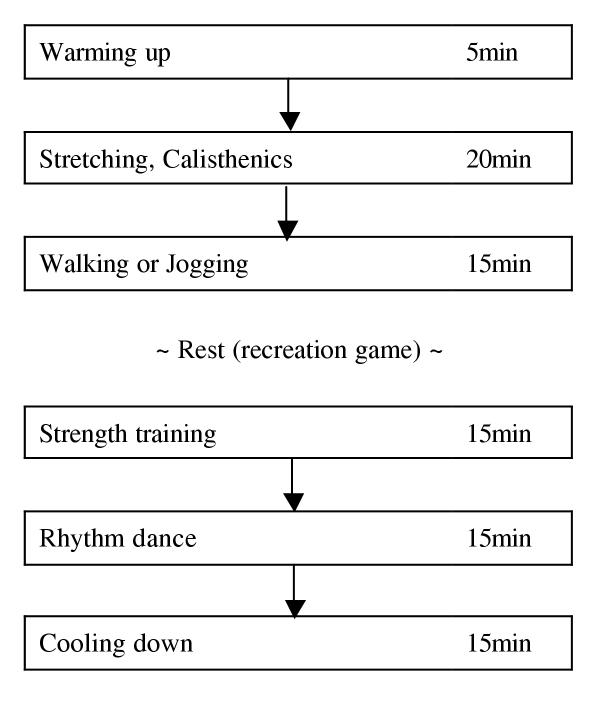

A 90-minute physical education class was carried out once a week based on the program shown in Figure 1. Walking, jogging or rhythm dance was conducted at 40–60% of VO2max for each subject, as calculated by Karvonen's formula [18]. Participation in the physical education class was not forced. On the average, each subject participated in about 80% of the exercises throughout the study over 24-month period.

Figure 1.

Basic exercise training program in the physical education class for menopausal women.

In the beginning, all subjects were each given a pedometer and asked to record the number of their daily steps for a week, under the conditions of not having any other kind of exercise and continuing their ordinary lifestyles. After the week was up, they brought their records of their calculated average daily steps. Each participant of the exercise group was asked to increase the number of her steps per day at least 2,000 to 3,000 more than her calculated average daily steps.

Method of evaluation

Evaluations were carried out in the participation at the beginning and after 6 months, 15 months, and 24 months. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from height and weight. The blood examination was carried out during 7–8 p.m., before eating. As for premenopausal women, the schedule of blood collection was adjusted in order to complete blood collection in the luteal phase. The serum was recovered following centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 15 minutes and then stored at 4°C. All analyses were completed within 48 hours. Samples were analyzed for estradiol (E2), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLC),triglyceride (TG) and lipid peroxidation (LPO). E2 and FSH were assayed by radioimmunoassay. The TC in the serum was assayed by the cholesterol oxidase method (Cholesterol E-test Wako, Wako Co., Osaka, Japan). The HDLC in the serum was assayed by the phosphotungstic acid-magnesium chloride precipitation method (HDL cholesterol E-test Wako, Wako Co., Osaka, Japan). The TG in the serum was assayed by glycerol-3-phosphate oxidase method (Triglyceride E-test Wako, Wako Co., Osaka, Japan). The LPO in the serum was measured using the assay system described by Ohkawa et al.[19]. The TC: HDLC ratio was adopted according to the atherogenetic index.

Analysis method

Changes in the number of daily steps and the blood analysis data over the four evaluations were detected by 2 × 4 repeated measures of ANOVA. Difference in mean values at the same time between the exercise group and the control group were compared. Multiple regression analysis was conducted for all exercise subjects between: (a) change of TC, HDLC, TC: HDLC and LPO for 24 months and age, BMI and average number of daily steps for 24 months; and (b) value of TC, HDLC, TC: HDLC and LPO at each evaluation time and age, BMI, average number of daily steps for each of the intervals between the evaluation times and the initial value. This was done by increasing and decreasing variables by AIC. Comparisons between the two groups at certain time points were made using t-test with a Bonferroni correction for multiple measures. The level of significance in each analysis was P < 0.05.

Results

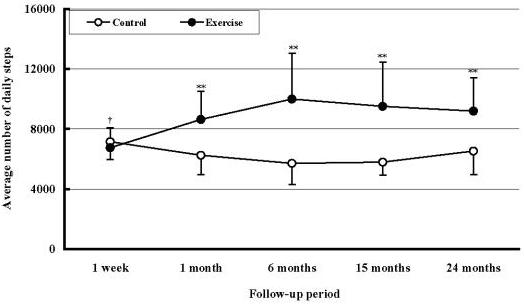

The average number of daily steps at entry (for a week) was 6,740 ± 1,326 steps in the exercise group and 7,149 ± 1,202 steps in the control group (P > 0.05). Figure 2 shows the average number of daily steps taken at 1,6,15 and 24 months in the both groups. The average daily steps of the exercise group at mentioned points were between 8,500 and 11,000 steps. Compared to the first week, the exercise group's average daily steps at 1,6,15 and 24 months after the moderate exercise started was significantly higher (P < 0.01) than the first week. In the control group, the number of daily steps ranged from about 5,700 to 6,500 steps. Compared with the first-week value, no significant difference at the taken intervals could be detected (F = 1.9, P > 0.05). The average daily steps of the exercise group (at 1,6,15 and 24 months after the moderate exercise started) were significantly (P < 0.01) higher than those of the control group.

Figure 2.

Changes in average of number of daily steps in the exercise and the control groups at 1,6,15 and 24 months after the moderate exercise started. †: A significant difference at P < 0.01 was detected between the average daily steps during a week preceding the physical education class and that of the selected months during the follow-up period. **: Significantly different from the control group. **P < 0.01.

Table 2 shows changes of TC, HDLC and LPO concentrations and TC : HDLC ratio in both groups for 24 months. In the control group, the levels of TC, HDLC, TG, LDLC, TC : HDLC ratio and LPO did not change significantly for 24 months. By applying 2 × 4 repeated measures of ANOVA, a significant interaction between the exercise group and the control group in the changes of TC (F = 3.92, P < 0.05), HDLC (F = 4.08, P < 0.05) and TC : HDLC ratio (F = 4.27, P < 0.05) could be observed. HDLC at 24 months in the exercise group was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than that in the control group. In the exercise group, TC : HDLC ratio at 24 months in the exercise group was significantly lower (P < 0.05) than those in the control group.

Table 2.

Change in the value over 24 months in the exercise group and the control group

| Start | 6 M | 15 M | 24 M | |||||

| mean | (SD) | mean | (SD) | mean | (SD) | mean | (SD) | |

| Exercise group (N = 14) | ||||||||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 218.2 | (52.2) | 200.6 | (31.8) | 197.3 | (38.2) | 193.3 | (24.8)* |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 59.0 | (13.5) | 62.7 | (13.0) | 64.9 | (17.9) | 68.4 | (12.9)*,† |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 133.8 | (51.4) | 100.9 | (35.6) | 89.0 | (40.5) | 87.3 | (41.8) |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 109.7 | (29.7) | 104.1 | (29.2) | 94.1 | (34.1) | 90.8 | (27.3) |

| TC:HDLC ratio | 3.91 | (1.46) | 3.33 | (0.81) | 3.35 | (1.35) | 3.00 | (1.03)*,† |

| Lipid peroxidation (nmol/ml) | 3.36 | (1.10) | 3.21 | (0.96) | 2.89 | (0.79) | 2.70 | (0.78) |

| Control group (N = 13) | ||||||||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 210.0 | (24.2) | 194.9 | (24.5) | 220.5 | (32.2) | 224.4 | (32.3) |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 56.7 | (16.6) | 56.6 | (13.5) | 57.3 | (13.5) | 56.7 | (14.6) |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 140.9 | (40.0) | 121.8 | (39.8) | 140.7 | (36.4) | 138.2 | (36.2) |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 119.2 | (28.4) | 108.9 | (26.1) | 118.6 | (31.4) | 124.2 | (36.1) |

| TC:HDLC ratio | 4.11 | (1.31) | 3.52 | (1.15) | 3.95 | (0.98) | 4.16 | (1.13) |

| Lipid peroxidation (nmol/ml) | 4.15 | (1.02) | 3.24 | (0.88) | 3.30 | (1.07) | 3.58 | (0.79) |

The significant differences were detected using 2 × 4 repeated measures of ANOVA:*P < 0.05, †P < 0.05 compared to the control group by t-test with a Bonferroni correction.

The results of multiple regression analysis of the values of TC, HDLC and LPO and TC: HDLC ratio at the start and 24 M evaluations are shown in Table 3. There was no effect of the considered factors on each value at the start of the study. The quantity of number of daily steps affected negatively the value of TC (F = 13.4, P < 0.01) and the TC: HDLC ratio (F = 12.8, P < 0.01) and positively the value of HDLC (F = 8.7, P < 0.05) at 24 M evaluations. The postmenopausal group was negatively related to the HDLC value (F = 6.9, P < 0.05). Age and postmenopause were positively related to the TC: HDLC ratio (F = 22.9, P < 0.01).

Table 3.

Multiple regression analysis of the value of TC, HDLC, TC:HDLC ratio and LPO at the start (Start) and after 24 months (24 M) in the exercise group

| TC | HDLC | TC:HDLC | LPO | |||||

| Start | 24 M | Start | 24 M | Start | 24 M | Start | 24 M | |

| Explanatory variable | ||||||||

| Age | 0.004 (0.000) |

0.883 (3.182) |

-0.619 (1.450) |

-1.138 4.971) |

0.759 (2.141) |

1.502** (15.78) |

0.876 (0.317) |

-0.299 (0.148) |

| BMI | 0.086 (0.088) |

0.327 (0.278) |

-0.607 (8.543) |

-0.234 (1.076) |

0.574 (5.322) |

0.334 (3.965) |

0.166 (0.794) |

0.296 (0.735) |

| Number of daily steps | -0.496 (2.615) |

-0.919** (34.74) |

0.182 (0.531) |

0.848* (8.720) |

-0.601 (5.178) |

-1.019** (12.86) |

0.470 (0.271) |

0.595 (1.884) |

| Postmenopausal Yes(1)/No(0) |

-0.347 (0.516) |

0.333 (1.041) |

-0.542 (1.730) |

-0.984* (6.913) |

0.402 (0.939) |

1.002** (22.92) |

0.123 (1.139) |

-0.627 (1.207) |

| Premenopausal Yes(1)/No(0) |

0.035 (0.003) |

0.859 (3.160) |

-0.340 (0.351) |

-0.014 (3.364) |

-0.674 (1.248) |

-1.470** (13.57) |

0.574 (0.320) |

-0.330 (0.153) |

| Proportion | 0.457 | 0.781* | 0.597 | 0.714* | 0.597 | 0.843** | 0.416 | 0.334 |

| F value | 1.349 | 5.715 | 2.376 | 3.992 | 2.376 | 8.576 | 1.142 | 0.804 |

Statistically significant: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Values are standard partial regression coefficient (F value). BMI: Body mass index, Start: at the start of this study, 24 M: after 24 months

Table 4 presents the result of the multiple regression analysis of change in TC, HDLC, TC : HDLC ratio and LPO over 24 months. The values were mostly influenced by the amount of TC (F = 89.8, P < 0.01), the TC: HDLC ratio (F = 23.2, P < 0.01) and the LPO (F = 12.0, P < 0.05) by each initial value. The number of daily steps affected the change in the value of TC (F = 6.8, P < 0.05) and HDLC (F = 7.2, P < 0.05).

Table 4.

Multiple regression analysis of change volume of TC, HDLC, TC:HDLC ratio and LPO over 24 months in the exercise group

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Age | -0.095 (0.901) | -0.156 (0.402) | 0.055(1.270) | -0.207 (0.056) |

| BMI | -0.125(1.231) | -0.433 (1.954) | 0.190 (0.126) | -0.062 (0.559) |

| Number of daily steps | 0.346 (6.807)* | -0.702 (7.169)* | 0.283 (0.469) | -0.139(1.006) |

| Initial value | 1.506(89.83)** | 0.239 (0.610) | 0.999 (23.27)** | 0.898 (12.04)** |

| Proportion | 0.919** | 0.572 | 0.618* | 0.896** |

| F value | 25.710 | 3.005 | 3.643 | 9.136 |

statistically significant: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Values are standard partial regression coefficient (F value), BMI: Body Mass Index, ![]() : the value at the start subtracted from the vale at 24 months.

: the value at the start subtracted from the vale at 24 months.

Discussion

It has been reported that TC, LDLC and TG concentrations increase from 30–35-year-olds to 50–60-year-olds, and the serum lipid profile becomes almost constant after then in women [20,21]. The rises have been reported to be 20–30 mg/dl in TC, 30–40 mg/dl in LDLC and 35–40 mg/dl in TG [20]. Especially, TC and LDLC concentrations remarkably increase between 4 years before and 1 year after menopause [22], and there is a large difference between premenopausal and postmenopausal women [23-25]. HDLC concentration decreases a little with aging from age 20 [20,26,27], and the characteristic change around menopause is not observed. In this study, all subjects were around menopausal age; in fact, six subjects changed to postmenopausal from menopausal status and five subjects changed to menopausal from premenopausal status during the course of the study: Taking the age and the menstruation status into consideration, the subjects were put in the stage in which serum lipids were most easy to deteriorate. It is a primary goal to stop the deterioration of the lipids in women in this particular stage. Our results showed that HDLC and TC : HDLC ratio were significantly improved in the exercise group. HDLC after 24 months in the exercise group was higher compared with the control group. Regarding TC: HDLC ratio after 24 months, the obtained values in the exercise group were significantly lower than that in the control group. It is evident from these that exercise stops the deterioration of the lipid profile in women around menopause. There are some reports with results similar to ours [5,24,28,29]. It is possible to assume that a woman close to menopausal age would not obstruct the improvement of serum lipids through exercise. Moreover, the results obtained showed that the most influential factor was each initial value marking the improvement of TC: HDLC ratio and LPO; there are similar reports by others [6,10,30-32]. Consequently, we arrive at the conclusion that exercise is very useful for women around menopause not only to prevent the value from deteriorating but also to return the levels that have already deteriorated.

Consider now the factors related to the improvement of the serum lipids. The postmenopausal state affected the values of HDLC and TC: HDLC ratio. This fact is known as the effect of estrogen decrease. It was shown that the values of TC, HDLC and TC: HDLC ratio were related to the number of daily steps, which in turn affected the changes of TC and HDLC for 24 months. These results demonstrate that increasing of the number of daily steps work improves or at least maintains a good levels of the serum lipids. Irie et al.[33] reported that an increased number of steps was significantly correlated with increased HDLC, and this fact supports our view. In our study, the average of the number of steps per day for the first week was about 6,500. This is almost the same as the average of the number of daily steps in Japanese homemakers [34], and it reflects the lifestyle of those who do not move very much. By encouraging the increase in the number of daily steps taken, our subjects increased them to about 9,000. Duncan et al. [35] found that HDLC concentration and TC : HDLC ratio improved not in their aerobic group or brisk group, but in their strolling group. Reaven et al.[36] also noted that HDLC concentrations were the highest in the group in which the physical activity level was light. It is reasonable to suppose that the improvement can be expected even in exercise of low intensity. In the view of Blair et al.[37], the response to exercise depends on neither the intensity nor the length of the training period, duration of exercise session, or the frequency, etc. When considering the exercise conditions applied until now by research on women, the frequency was mostly 3–5 times/week and the duration of an exercise session was 20–60 minutes. There is a difference between longitudinal research and cross-sectional research in the training period; it is between 10 weeks and 12 months and between 3 years and 5 years, respectively. The effect of exercise on the lipids is different among various studies conducted in longitudinal research. On the other hand, the value of lipids in trained women is obviously better than in untrained women in cross-sectional research. This fact indicates that the lipids are surely improved owing to long-term exercise. In our study, it seems that suitable results were obtained because the period of exercise was long, though the intensity of exercise was low.

Although the physiological mechanisms that involved in the decrease of TC and the increase of HDLC due to low intensity physical activity were not directly examined in the present study, several possible mechanisms have been proposed to explain them. Some investigators have demonstrated that aerobic exercise increases both plasma lipoprotein lipase and lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase activities [38,39]. It would be expected that the same mechanisms might also been presented in the menopausal women. To clarify the related mechanisms, more investigations need to be carried out.

Turn now to the role of the antioxidation that estrogen and LPO had. LPO oxidized the low-density lipoproteins (LDL), and the oxidation of LDL is incorporated by macrophages, becomes a foam cell, and then it becomes deposited in the arterial vessel wall. It is said that it worsens arteriosclerosis, and it is considered in the meantime that estrogen suppresses the LPO. Since estrogen is failing around menopause, it appears that LPO increases. It is necessary to control the increase of LPO and LDL, and toward this end, exercise is expected to play an important role. There is a report on the effect of exercise on the oxidation of LDL, whose production could be suppressed by 10-month exercise [40]. There is no other survey examining on the effect of long-term exercise. In many surveys, it was found that acute exercise accelerated the generation of LPO [41,42]. In this study, LPO concentration decreased, though not significantly, and the factor that affected the alteration of LPO could not be clarified by multiple regression analysis. In the future, it will be necessary to sufficiently examine the effect of long-term exercise on the generation of LPO and oxygen action including the effects of menstruation.

In follow-up studies involving physical education class, the number of persons who participate throughout the entire term of investigation is an important factor. Participation rate of about 60% has been reported [43]. In the current study, moderate exercise regimen had a practice rate 62.5% for 24 months. Thus, we can speculate that moderate exercise, as applied in our study, may improve the practice rate.

We have undertaken another study a large number of controls and exercise group. Our goal is to overcome a number of weakness points we have been facing in the present investigation including: small subjects' numbers and lack of dietary control. In addition, it would have been desirable to perform analyses by dividing the subjects into the same status of menopause. However, in the present study the number of subjects was not enough to do so. The results of upcoming research would further our understanding of the effects of moderate exercise and serum lipids status in women.

Conclusion

On the basis of the materials discussed here, it was concluded that daily exercise as well as increasing the number of daily steps as a moderate exercise can improve the profile of serum lipids in menopausal women. However, it is difficult to clarify the relationship between blood lipids and the low intensity physical activity in humans. More work needs to be done to understand blood lipid profiles associated with exercise.

Competing interests

None declared

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Takatomi town (Gifu, Japan) office for cooperating with our study and Dr. Toshiya Itoh from Gihoku hospital for the technical support in this study. This study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan (Grant no. 08780091 and 07772270).

Contributor Information

Hiroko Sugiura, Email: hirokos@cc.gifu-u.ac.jp.

Haruo Sugiura, Email: sugiura@cc.gifu-u.ac.jp.

Kazue Kajima, Email: kajima@cc.gifu-u.ac.jp.

Seyed Mohammad Mirbod, Email: mirbod@cc.gifu-u.ac.jp.

Hirotoshi Iwata, Email: eisei@cc.gifu-u.ac.jp.

Toshio Matsuoka, Email: matsuoka@cc.gifu-u.ac.jp.

References

- Blum A, Cannon RO. Effects of oestrogens and selective oestrogen receptor modulators on serum lipoproteins and vascular function. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1998;9:575–586. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199812000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardos A, Casadei B. Hormone replacement therapy and ischaemic heart disease among postmenopausal women. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1999;6:105–112. doi: 10.1177/204748739900600207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamoto T, Komachi Y, Inada H, Doi M, Sato S, Kitamura A, Iida M, Konishi N. Trends for coronary heart disease and stroke and their risk factors in Japan. Circulation. 1989;79:503–515. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyden TW, Pamenter RW, Going SB, Lohman TG, Hall MC, Houtkooper LB, Bunt JC, Ritenbaugh C, Aickin M. Resistance exercise training is associated with decreases in serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in premenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:97–100. doi: 10.1001/archinte.153.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindheim SR, Notelovitz M, Feldman E, Larsen S, Khan FY, Lobo RA. The independent effects of exercise and estrogen on lipids and lipoproteins in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:167–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motoyama M, Sunami Y, Kinoshita F, Irie T, Sasaki J, Arakawa K, Kiyonaga A, Tanaka H, Shindo M. The effects of long-term low intensity aerobic training and detraining on serum lipid and lipoprotein concentrations in elderly men and women. Eur J Appl occup Physiol. 1995;70:126–131. doi: 10.1007/BF00361539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean PW, Oden G, Crouse SF, Brown JA, Green JS. Lipid and lipoprotein changes in women following 6 months of exercise training in a worksite fitness program. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1996;36:54–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuit AJ, Schouten EG, Miles TP, Evans WJ, Saris WHM, Kok FJ. The effect of six months training on weight, body fatness and serum lipids in apparently health elderly Dutch men and women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:847–853. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell KD, Bachorik PS, Ayerle RS. Changes in plasma lipid and lipoprotein levels in men and women after a program of moderate exercise. Circulation. 1991;65:477–484. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.65.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponjee GAE, Janssen EME, Hermans J, van Wersch JWJ. Effects of long-term exercise of moderate intensity on anthropometric values and serum lipids and lipoproteins. Eur J clin Chem clin Biochem. 1995;33:121–126. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1995.33.3.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieman DC, Warren BJ, O'Donnell KA, Dotson RG, Butterworth DE, Henson DA. Physical activity and serum lipids and lipoproteins in elderly women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993; 41:1339–1344. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandvik L, Erikssen J, Thaulow E, Erikssen G, Mundal R, Rodahl K. Physical fitness as a predictor of mortality among health, middle-age Norwegian men. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:533–537. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302253280803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen LB. Physical activity and physical fitness as protection against premature disease or death. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1995;5:318–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1995.tb00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Am Coll Sports Med Guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Philadelphia PA, Lea and Feliger, 1995;5:161–173. [Google Scholar]

- Pate RR. Physical activity and public health: A recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. JAMA. 1995;273:402–407. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Hyde RT, Wing AL, Hsieh CC. Physical activity, all-cause mortality, and longevity of college alumni. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:605–613. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198603063141003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AS, Connett J, Jacobs DR, Rauramaa R. Leisure-time physical activity levels and risk of coronary heart disease and death: The multiple risk factor intervention trial. JAMA. 1987;258:2388–2395. doi: 10.1001/jama.258.17.2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karvonen MJ, Kentala E, Mustala O. The effects of training on heart rate. A longitudinal study. Ann Med Exper Biol Fenn. 1957;35:307–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawa H, Ohishi N, Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem. 1979;95:351–358. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson JC, Grook D, Goldsland IF. Influence of age and menopause on serum lipids and lipoproteins in healthy women. Atherosclerosis. 1993;98:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(93)90225-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabuchi H. Current state of and recent trends in serum lipid levels in the general Japanese population. J Arterioscler Thromb. 1996;2:122–132. doi: 10.5551/jat1994.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukami K, Koike K, Hirota K, Yoshikawa H, Miyake A. Perimenopausal changes in serum lipids and lipoproteins: a 7-year longitudinal study. Maturitas. 1995;22:193–197. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(95)00927-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen J, Nilas L, Christiansen C. Influence of menopause on serum lipids and lipoproteins. Maturitas. 1990;2:321–331. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(90)90012-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal JA, Matthews K, Fredrikson M, Rifai N, Schniebolk S, German D, Steege J, Rodin J. Effects of exercise training on cardiovascular function and plasma lipid, lipoprotein, and apolipoprotein concentrations in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Arterioscler Thromb. 1991;11:912–917. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.11.4.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean PW, Crouse SF, O'Brien BC, Rohack JJ, Brown JA. The effects of menopausal status and exercise training on serum lipids and the activities of intravascular enzymes related to lipid transport. Metabolism. 1998;47:377–383. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(98)90046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Wu X, Zhang Y. Relationship of menopausal status and sex hormones to serum lipids and blood pressure. Int J Epidemiol. 1990;19:297–302. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beresteijn EC, Korevaar JC, Huijbregts PCW, Schouten EG, Burema J, Kok FJ. Perimenopausal increase in serum cholesterol: a 10-year longitudinal study. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:383–392. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas TR, Adeniran SB, Iltis PW, Aquiar CA, Albers JJ. Effects of interval and continuous running on HDL-cholesterol, apoproteins A-1 and B, and LCAT. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1985;10:52–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardman AE, Hudson A. Brisk walking and serum lipid and lipoprotein variables in previous sedentary women: effects of 12 weeks of regular brisk walking followed by 12 weeks of detraining. Br J Sports Med. 1994;28:261–266. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.28.4.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokey EA, Tran ZV. Effects of exercise training on serum lipid and lipoprotein concentrations in women: A meta-analysis. Int J Sports Med. 1989;10:424–429. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1024937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JO, Thiel J, Heller PA, Markon C, Fletcher G, DiGirolamo M. Differences in effects of aerobic exercise training on blood lipids in men and women. Am J Cardiol. 1989; 63:254–256. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90297-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago MC, Leon AS, Serfass RC. Failure of 40 weeks of brisk walking to alter blood lipids in normolipemic women. Can J Appl Physiol. 1995;20:417–428. doi: 10.1139/h95-033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie M, Nagata S, Ikeda M, Miyata M. Effects of walking during all weekdays, holidays, and at work on mental and physical health in workers. Sangyo Eiseigaku zasshi. 1998;40:7–14. doi: 10.1539/sangyoeisei.kj00001990715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatano Y. The walking for the health. J Cli Sports Med. 1992;9:129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan JJ, Gordon NF, Scott CB. Women walking for health and fitness. JAMA. 1991;266:3295–3299. doi: 10.1001/jama.266.23.3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaven PD, McPhillips JB, Barrett-Connor EL, Criqui MH. Leisure time exercise and lipid and lipoprotein levels in an older population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38:847–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb05698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair SN, Kohl HW, Gordon NF. How much physical activity in good for health? Annu Rev Public Health. 1992;13:99–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.13.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean PW, Crouse SF, O'Brien BC, Rohack JJ. Influence of cholesterol status on blood lipid and lipoprotein enzyme responses to aerobic exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:472–480. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.2.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann R, Engler H, Honegger R, Riesen W, Spinas GA. Alterations of lipolytic enzymes and high-density lipoprotein subfractions induced by physical activity in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Clin Invest. 2001;31:37–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2001.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasankari TJ, Kujala UM, Vasankari TM, Ahotupa M. Reduced oxidized LDL levels after a 10-month exercise program. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:1496–1501. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199810000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzatico F, Pansarasa O, Bertorelli L, Somenzini L, Della VG. Blood free radical antioxidant enzymes and lipid peroxides following long-distance and lactacidemic performances in highly trained aerobic and sprint athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1997;37:235–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy KV, Kumar TC, Prasad M, Reddanna P. Pulmonary lipid peroxidation and antioxidant defenses during exhaustive physical exercise: the role of vitamin E and selenium. Nutrition. 1998;14:448–451. doi: 10.1016/S0899-9007(98)00016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldridge NB. A handbook of health enhancement and disease prevention. In: Matarazzo MD, Weiss SM, Herd JA, Miller NE, editor. New York John Wiley. 1984. pp. 467–487. [Google Scholar]