Abstract

Phosphoribosyl transferases (PRTs) are essential in nucleotide synthesis and salvage, amino acid, and vitamin synthesis. Transition state analysis of several PRTs has demonstrated ribocation-like transition states with a partial positive charge residing on the pentose ring. Core chemistry for synthesis of transition state analogues related to the 5-phospho-α-d-ribosyl 1-pyrophosphate (PRPP) reactant of these enzymes could be developed by stereospecific placement of bis-phosphate groups on an iminoaltritol ring. Cationic character is provided by the imino group and the bis-phosphates anchor both the 1- and 5-phosphate binding sites. We provide a facile synthetic path to these molecules. Cyclic-nitrone redox methodology was applied to the stereocontrolled synthesis of three stereoisomers of a selectively monoprotected diol relevant to the synthesis of transition-state analogue inhibitors. These polyhydroxylated pyrrolidine natural product analogues were bis-phosphorylated to generate analogues of the ribocationic form of 5-phosphoribosyl 1-phosphate. A safe, high yielding synthesis of the key intermediate represents a new route to these transition state mimics. An enantiomeric pair of iminoaltritol bis-phosphates (L-DIAB and D-DIAB) was prepared and shown to display inhibition of Plasmodium falciparum orotate phosphoribosyltransferase and Saccharomyces cerevisiae adenine phosphoribosyltransferase (ScAPRT). Crystallographic inhibitor binding analysis of L- and D-DIAB bound to the catalytic sites of ScAPRT demonstrates accommodation of both enantiomers by altered ring geometry and bis-phosphate catalytic site contacts.

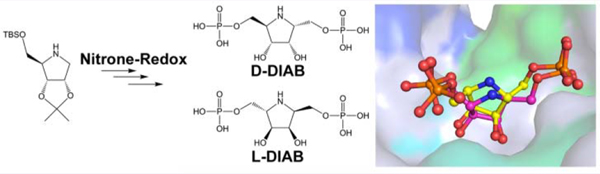

Graphical Abstract

Essential steps in the synthetic pathways of purine and pyrimidine nucleotides, histidine and tryptophan, NAD+, purine and pyrimidine base salvage, tetrahydromethanopterin synthesis, and other secondary metabolites depend on the transfer of the ribose 5-phosphate group from 5-phospho-α-d-ribose 1-pyrophosphate (PRPP) to an acceptor molecule.1 Several phosphoribosyltransferases have been subjected to transition state analysis by kinetic isotope effects and quantum chemical analysis to reveal ribocation-like transition states.2–5 The few transition state analogues described for phosphor-ibosyltransferases have been focused on the ribosylated product of the reaction rather than the PRPP ribosyl donor.5–8 We sought to provide ribocation transition state mimics of PRPP as potential inhibitor probes for this relatively untargeted class of important biosynthetic enzymes. Transition state analogues are chemically stable mimics of the transition states of their cognate enzymes. For the PRPP transferases, the challenge is to make chemically stable mimics of PRPP, which is an intrinsically chemically unstable molecule. Iminoribitols are known transition state mimics for ribosyltransferases (Figure 1). Direct iminoribitol mimics of PRPP face a problem of chemical instability with substitution of the anomeric carbon of ribose with both imino and pyrophosphate groups. Therefore, we approached the synthesis by insertion of a methylene bridge between the anomeric carbon and phosphate group, to generate bis-phosphorylated derivatives of 2,5-dideoxyaltritol (Scheme 1). The synthesis of d- and l-2,5-dideoxy-2,5-imino-altritol 1,6-bisphosphate (D-DIAB and L-DIAB) are described together with inhibition profiles for several phosphoribosyltransferases and the crystal structures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae adenine phosphoribosyltransferase (ScAPRT) in complex with both enantiomers.

Figure 1.

Ribocationic transition states for human purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP), Plasmodium falciparum hypoxanthine-guanine-xanthine phosphoribosyltransferase, their transition state analogues, and the rationale for synthesis of the bis-phosphate iminoaltritols for other phosphoribosyltransferases (PRTases).

Scheme 1.

Targets and Retrosynthetic Analysis

Five-membered cyclic nitrones add versatile functionality in the synthesis of cyclic amines. For example, the syntheses of pyrrolidine alkaloids, aza-sugars, and other natural products rely on the robustness of the transformations available to these nitrones.9–13 A general strategy for the synthesis of nitrones that allows facile access to many diastereoisomers of the iminosugar motif has been the focus of several studies.14–16

We have reported several strategies to incorporate five-membered N-heterocycles and iminosugars into small-molecule, rationally designed, transition-state analogue inhibitors of ribosyltransferases implicated in cancer, infectious diseases, gout, and gastric ulcers.17 Here, we expand the approach to synthesize bis-phosphate D-DIAB (Scheme 1), a putative transition-state analogue inhibitor of phosphoribosyltransferases. Inhibitors designed to inhibit activity of glycosidases have occasionally shown surprising levels of activity for their enantiomers.18–21 Thus, we also developed an efficient synthesis of enantiomer L-DIAB. We previously reported the synthesis of alcohol 2 (Scheme 1) with the 2,5-cis-dihydroxymethyl configuration, from iminoribitol imine 5a by addition of a lithiated dithiane, hydrolysis, and reduction.22 This is a long and difficult synthesis. A facile route to 2 is desirable. We considered the previously synthesized nitrone 6a23 as a superior electrophile, but safety is a concern in the use of selenium dioxide/acetone/hydrogen peroxide24 in its synthesis–especially for large scale reactions. A nitrone/ hydroxylamine/amine redox-strategy12,25,26 (Scheme 1) would use iminoribitol derivative 7 as a starting point for a number of stereoisomers and eliminate the need to resynthesize each stereoisomer from different sugars.14

With the exception of a few literature examples,27 the 2,5-trans-hydroxymethyl-configuration (cf. target D-DIAB), resulting from stereoselective additions to cyclic-nitrones or imines of this type, has been installed in one of two ways: (i) where the configuration of the 3-position induces the favored 2,3-trans-relationship12 or (ii) where the configuration of the 2-position has been inverted following addition of a suitable nucleophile. We envisioned a strategy employing reoxidation12,13,28 of a vinyl-adduct of hydroxylamine after addition of Grignard29–31 to nitrone 6a, with subsequent oxidation/reduction (redox) steps, which could afford the desired 2,5-trans-configuration in compound 4 (Scheme 1). The intermediate α,β-unsaturated ketonitrone 3 in this case would double-up as a useful 2,5-trans-hydroxymethyl (2,3-cis-hydroxymethyl) synthon. An alternative synthon for this purpose has been utilized by Marradi and colleagues.28 However, the harsh conditions required for deprotection of this protected-hydroxymethyl equivalent limits the synthetic utility of the synthon in subsequent transformations; hence, we felt the vinyl group would allow for a wider range of functional group manipulations. We report, herein, expedient syntheses of two enantiomeric bis-phosphates D-DIAB and L-DIAB and improved synthesis of alcohol 2 from a common intermediate: iminoribitol derivative 7.

We also investigated the effects on enzyme catalysis and structural properties upon binding of the bis-phosphate transition-state analogue inhibitors to phosphoribosyltransferases adenine phosphoribosyltransferase (APRT; EC 2.4.2.7) and orotate phosphoribosyltransferase (OPRT; EC 2.4.2.10). These are examples of key enzymes in purine salvage and pyrimidine metabolism found among many organisms. The phosphoribosyltransferases catalyze the Mg2+-dependent reversible transfer of the 5-phosphoribosyl moiety from α-d-5- phosphoribosyl 1-pyrophosphate (PRPP) to adenine or orotate, resulting in the formation of adenosine mono-phosphate (AMP) or orotidine monophosphate (OMP) and inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi).32–34

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis of nitrone 6a23 was substantially improved by implementing the catalytic methylrhenium trioxide (MTO)35–37 oxidation of secondary amines to oxidize iminoribitol 7 (Scheme 2). Nitrones 6a (72%) and 6b (18%) were easily separable by a combination of recrystallization and chromatography in an excellent combined yield. We have successfully performed the MTO oxidation on a >20 g scale.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Nitrones via MTO and Improved Synthesis of Alcohol 2 a

aReagents and conditions: (i) MTO (0.2 mol %), H2O2 (30%) in CH2Cl2, r.t. then MeOH, 15 min, r.t. then dropwise addition of 7 in CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 0.5 h, 72% for 6a and 18% for 6b. (ii) Vinyl magnesium bromide, THF, −70 to 0 °C. (iii) Zn, AcOH, r.t., 4−16 h. (iv) Boc2O, MeOH, r.t., 1 h, 85% over 3 steps for 12a or CbzCl, K2CO3, PhMe, H2O, r.t., 1−3 h, 84% over 3 steps for 12b. (v) OsO4 (4 mol %), NMO, MeCN, H2O, r.t., 6 h. (vi) (1) NaIO4, H2O, EtOH, r.t., then (2) NaBH4, r.t., 5 min to 1 h, 93% over 3 steps for 2a and 87% over 3 steps for 2b.

Nucleophilic addition of vinyl-Grignard to nitrone 6a was highly efficient, yielding hydroxylamine 10 (Scheme 2) quantitatively and with complete stereoselectivity as expected on the basis of previous results.29,30 Reduction of the crude hydroxylamine afforded the free secondary amine 11, which could be protected with Boc (12a) or Cbz (12b) groups. Catalytic osmium tetroxide-mediated dihydroxylation of alkenes 12a and 12b, diol-cleavage using NaIO4 and reduction by NaBH4, yielded diols 2a and 2b in 80% and 73% yields, respectively, over six steps from nitrone 6a. The practical ease and enhanced safety profile of this route coupled with the high yields marks a vast improvement on the previously reported synthesis of alcohol 2a from iminoribitol 7.22

Next, we turned our attention to the synthesis of bis-phosphate D-DIAB (Scheme 3). Conversion of hydroxylamine 10 to the vinyl-nitrone 3 was achieved in moderate yield by catalytic MTO oxidation (36%)38 and was improved to 49% by utilizing stoichiometric TEMPO as the oxidant,13 while a standard MnO2 oxidation protocol proved sluggish. Vinyl-nitrone 3 was a bench-stable solid.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of bis-phosphate D-DIABa

aReagents and conditions: (i) MTO (0.2 mol %), H2O2 (30%) in CH2Cl2, r.t. then MeOH, 15 min, r.t. then dropwise addition of 10 in CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 0.5 h, 36%. (ii) TEMPO, CH2Cl2, r.t., 10 min, 49%. (iii) OsO4 (4 mol %), NMO, MeCN, H2O, r.t., 6 h. (iv) (1) NaIO4, H2O, EtOH, r.t., then (2) NaBH4, r.t., 5 min to 1 h, 47% over 3 steps. (v) Zn, AcOH, r.t., 4–16 h, quant. (vi) Boc2O, MeOH, r.t., 1 h, 74%. (vii) TBAF, THF, r.t., 85%. (viii) (1) N,N-diisopropyldibenzylphosphoramidite, CH2Cl2, r.t., 3 h, Ar(g) then (2) m-CPBA, −40 to 0 °C, 1 h, 91%. (ix) H2, 10% Pd/C, MeOH, r.t., 16 h; (x) MeOH, conc. HCl, r.t., 20 min, 76% over 3 steps. (xi) NaBH4, MeOH, r.t., 30 min, 27%.

Vinyl-nitrones similar to 3 have been synthesized by modified Stille coupling of thioimidates39 or by aldol-type reactions of α-methyl-substituted nitrones.40 The α,β-unsaturated ketonitrone is an interesting and relatively unexplored functional group,41 whose chemistry appears to be limited to addition to the ketonitrone functionality,42 cycloadditions,40 and unusual rearrangement reactions.41 Here, the osmium tetroxide-mediated dihydroxylation of the vinyl-nitrone 3 with subsequent cleavage by periodate and reduction by sodium borohydride yielded alcohol 13 with the desired configuration, presumably via the α-formyl-nitrone species.43 Thus, vinyl-nitrones–in this constrained bicyclic system–can furnish the α-hydroxymethyl amine after this redox sequence. The isopropylidene unit stabilizes such systems,39 and we have found that applying this type of nitrone redox chemistry to less constrained five-membered nitrogen heterocycles can be capricious. When vinyl-nitrone 3 was treated with sodium borohydride, saturated ethyl compound 19 was obtained, indicating conjugate addition of hydride to the vinyl-nitrone had occurred. Presumably rapid tautomerization of the resulting ene-hydroxylamine intermediate regenerates the nitrone, albeit in low yield.

Zinc-mediated reduction of hydroxylamine 13, N-Boc-protection, and silyl-deprotection furnished diol 16 in 63% yield over three steps (Scheme 3). To prepare the bis-phosphate ester, we chose to employ standard phosphoramidite coupling. Initially, double installation of di-tert-butyl phosphate was attempted via di-tert-butyl-N,N-diisopropylphosphoramidite with in situ oxidation by m-CPBA, for a putative single-step, final, global deprotection. However, the product contained impurities, some of which were identified as the H-phosphonates.44 These H-phosphonates may have arisen from facile β-elimination of the intermediate phosphite species, driven by the steric strain of the crowded environment of the 1,2,3-cis-setup. The installation of the tert-butyl phosphate by exactly this method is entirely possible in a less-crowded environment.5 Thus, benzyl phosphate esters were installed instead, by the same phosphoramidite methodology. With the β-elimination pathway no longer available to the intermediate dibenzyl-phosphite, the bis-phosphate ester 17 could be prepared by this method with a yield of 91%. Hydrogenation of the bis-dibenzyl phosphate ester followed by global hydrolysis afforded bis-phosphate D-DIAB.

In order to synthesize bis-phosphate L-DIAB, nitrone 6b was reduced with NaBH4, and hydroxylamine 20 was isolated cleanly from the reaction mixture in 96% yield (Scheme 4). Once again, this reduction was completely stereoselective. The MTO oxidation of hydroxylamine 20 yielded a chromato-graphically inseparable 1:1 mixture of nitrones 8 and 6b in 76% yield, along with 21% of recovered starting material. Vinyl magnesium bromide was added to the inseparable mixture 8/ 6b to afford a separable mixture of hydroxylamine adducts 21a/ b in 82% combined yield. Hydroxylamine 21a was reduced with zinc and N-Boc-protected to afford alkene 23, in 70% yield over two steps, which was then dihydroxylated, cleaved, and reduced to give alcohol 24 in 72% yield over three steps. Silyl-group deprotection of alcohol 24 by TBAF gave diol ent-16 ([α]d20 −51.6 (c = 1.55, CHCl3)), whose NMR spectroscopic data were identical to its enantiomer 16 ([α]d20 + 48.2 (c = 1.25, CHCl3)). Elaboration of diol ent-16 to bis-phosphate L-DIAB was identical to the sequence described for bis-phosphate D-DIAB (vide supra).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of bis-Phosphate L-DIABa

aReagents and conditions: (i) NaBH4, MeOH, r.t., 30 min, 96%. (ii) MTO (0.2 mol %), H2O2 (30%) in CH2Cl2, r.t. then MeOH, 15 min, r.t., then dropwise addition of 20 in CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 0.5 h, 76% (recovered 21% of 20). (iii) vinyl magnesium bromide, THF, −70 to 0 °C, 82% (combined yield; isolated yields 46% for 21a, 31% for 21b). (iv) Zn, AcOH, r.t., 4−16 h. (v) Boc2O, MeOH, r.t., 1 h, 70% over 2 steps. (vi) OsO4 (4 mol %), NMO, MeCN, H2O, r.t., 6 h. (vii) (1) NaIO4, H2O, EtOH, r.t., then (2) NaBH4, r.t., 5 min to 1 h, 72% over 3 steps. (viii) TBAF, THF, 16 h, 72%. (ix) (1) N,N-diisopropyldiben-zylphosphoramidite, CH2Cl2, r.t., 3 h, Ar(g), then (2) m-CPBA, −40 to 0 °C, 1 h, 58%. (x) H2, 10% Pd/C, MeOH, r.t., 16 h. (xi) MeOH, conc. HCl, r.t., 20 min.

Enzyme Inhibition Assays.

Recombinant N-terminal 6-His-tagged Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ScAPRT) was purified to homogeneity using a Ni-NTA His-tag affinity column, yielding approximately 60 mg of active enzyme from 20 g of cell culture.45 Enzyme activity was assessed by use of a recently published direct and sensitive fluorimetric assay, where 2,6-diaminopurine replaced adenine, the natural substrate (Figure 2).46

Figure 2.

Reaction catalyzed by ScAPRT monitored by the direct and sensitive decrease in fluorescence signal as 2,6-diaminopurine is converted to 2-amino-AMP in the absence or presence of D-DIAB or L-DIAB.

Fitting the inhibition data to the equation for competitive inhibition yielded Ki values of 8.7 ± 1.5 μM for D-DIAB and 14.9 ± 2.9 μM for L-DIAB (Table 1). These Ki values are lower than the previously reported 20 μM KM for PRPP.45 Thus, both stereoisomers are good inhibitors, binding better than the normal PRPP substrate.

Table 1.

Inhibition Data for bis-Phosphates D-DIAB and L-DIABa

| compound | Ki (ScAPRT/μM) | Ki (PfOPRT/μM) | Ki (HsOPRT/μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-DIAB | 8.7 ± 1.5 | 39 ± 4 | >200 |

| L-DIAB | 14.9 ± 2.9 | 103 ± 17 | >200 |

Initial reaction rates were used to calculate the Ki values for both compounds in triplicate.

The bis-phosphates D-DIAB and L-DIAB were also assayed for inhibition of Plasmodium falciparum (Pf) and human (Homo sapiens, Hs) orotate phosphoribosyltranferases (OPRTs). Both bis-phosphates inhibit PfOPRT and display 3-fold selectivity for D-DIAB (Table 1). HsOPRT showed no apparent inhibition at D-DIAB or L-DIAB concentrations of 200 μM (Table 1).

Transition state analogues for purine nucleoside phosphorylases (PNPs), 5′-methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (MTAP), and 5′-methylthioadenosine nucleosidase (MTAN) have also been synthesized in distinct enantiomeric forms to examine their differential interaction with target enzymes. In the cases of human PNP, MTAP, and E. coli MTAN, the relative affinities were 1200, 9600 and 2250 more tightly bound, respectively, for the correct (3R,4S) configuration than for the incorrect (3S,4R) enantiomers of tight-binding inhibitors.47 D- and L-DIAB differ from tight-binding inhibitors by only a 2-to 3-fold binding discrimination for PfOPRT and ScAPRT. A distinguishing difference between these inhibitor classes is that the former inhibitors occupy the complete array of catalytic site interactions related to the transition state, while the D- and L-DIAB molecules reflect binding only to the PRPP domain.

Structure Determination and Overall Structure.

ScAPRT crystallized from (NH4)2SO4 had only sulfate at the active sites. D-DIAB and L-DIAB binding was obtained by ligand soaking (SI, Table S1). The molecular replacement using PHASER for structure determination resulted in a dimer model in the C2 space group.48 Electron density for the N-terminal His6 tag was not observed in either structure. Electron density was also not observed for loop II (residues Glu104 to Asp110) of chain B in the D-DIAB bound structure and the same loop of chain-A of the L-DIAB bound structure. All other amino acid residues were readily fitted into the electron density map. The densities of D-DIAB and L-DIAB are clearly defined in the structures. All resolved amino acid residues are in the most favored or are in the allowed regions of the Ramachandran plot (Table S2).

ScAPRT belongs to the type-I PRTs and is a homodimer (Figure 3 and Figure S1). Each monomer consists of five α-helices and nine β-sheets. The enzyme has two domains: domain 1 serves as a hood domain (residues 1 to 35) and a core domain (residues 36 to 178). The hood domain of ScAPRT contains α-helices (α1, 3−13; and α2, 31−35) and β-sheets (β1, 14−18; and β2, 25−30). The core domain of the enzyme consists of five parallel β-sheets (β3, 61−67; β4, 83−90; β7, 123−132; β8, 150−161; and β9, 173−178) and three α-helices (α3, 37−54; α4, 69−81; and α5, 136−148; Figure 3 and S1). The loop between two of the β-sheets (β5, 97−104; β6, 109−115) of the core domain is the catalytic loop.45 In the crystal structure, the transition-state inhibitors (D-DIAB and L-DIAB) are bound at the active sites of both subunits of the ScAPRT (Figures 4 and 5). Crystal soaking experiments with 1 mM adenine together with D-DIAB and L-DIAB gave adenine bound only to chain-A and chain-B subunits, respectively (Figures 3 and 5). In the adenine-free sites, the symmetry-related Tyr107 side chain occupies the adenine binding pocket. No magnesium ion density was seen at the active sites of any of the inhibitor-bound structures, despite the presence of 5 mM MgCl2 in the ligand soak solutions.

Figure 3.

Subunit structures of ScAPRT complexes with D-DIAB and L-DIAB. (A) Structural fold and superposition of the ScAPRT-d-DIAB (brick red) and ScAPRT-L-DIAB complexes (light blue). Loop I is from Asn19 to Gly24. Loop II is from Lys105 to Gly108, and loop III is from Asp163 to Lys165. B and C are the structural superposition of ScAPRT-d-DIAB (brick red) and ScAPRT-l-DIAB (light blue), respectively with (B) unliganded ScAPRT (cyan) and (C) ScAPRT-sulfate bound (pink). (D) Superimposition of ScAPRT-d-DIAB (brick red) and ScAPRT-l-DIAB (light blue) with ScAPRT-sulfate bound (pink), showing no significant loop movement in these structures.

Figure 4.

Stereoview omit maps of D- and L-DIAB at the active sites of ScAPRT (A, B) and atomic numbering of the enantiomers in the crystal structures (C, D). (A) The omit (Fo−Fc) difference electron density map of the D-DIAB structure from subunit A. D-DIAB is added to the map as a stick model. (B) The omit (Fo−Fc) difference electron density map of the L-DIAB structure with L-DIAB added as a stick model. The (Fo−Fc) difference maps were calculated after 15 cycles of omit refinement by REFMAC5, leaving out the active site ligand. The contour levels are at 2.5σ for the D-DIAB (PDB code 5VJN) and the L-DIAB complexes (PDB code 5VJP). Atomic numbering of the D-DIAB (C) and L-DIAB (D) used in the crystal structure contacts.

Figure 5.

Stereoviews of the active site of ScAPRT complexed with D-DIAB (subunit A) and L-DIAB (subunit B). Panels A and B are the active site residue interactions with D-DIAB and L-DIAB, respectively. Hydrogen bond interactions are shown by dotted lines. The red spheres are water molecules interacting with D-DIAB and L-DIAB. (C) Superimposition of ScAPRT catalytic sites with bound D-DIAB and L-DIAB. The displacement of the imino-altritol rings is apparent. The superimposed sulfate from the ScAPRT-sulfate structure shows its position in the active site corresponding to the β−1-phosphate of the PRPP pyrophosphate.

Binding of D-DIAB, L-DIAB and Adenine.

ScAPRT with D-DIAB has been solved to 1.78 Å resolution (Figure S1). D-DIAB is bound in the active site with low B-factors, similar to the surrounding protein residues. The O2P of D-DIAB is hydrogen bonded to water-144 (Wat144). O3 makes hydrogen bond interactions with Wat60 and (OD1)Asp130. O4 of D-DIAB makes hydrogen bond interactions with Wat29 and (OD2)Asp129. The O4P has hydrogen bond interactions with Wat88 and (OG1)Thr134. The oxygen of O5P is hydrogen bonded to Wat24. Hydrogen bond partners for O6P include (OG)Ser137 and Wat213. The nitrogen atom N1 of the iminosugar ring has hydrogen bond interactions with Wat203 (Figure 5).

L-DIAB in complex with ScAPRT was solved to 1.98 Å resolution. L-DIAB is bound to the ScAPRT active site with contacts similar to D-DIAB, but in the reverse orientation (Figure S1). The interactions of L-DIAB with the enzyme are similar to the D-DIAB bound structure, except there are fewer hydrogen bond interactions in the L-DIAB-bound structure. The oxygen of O1P is hydrogen bonded to Wat14. The O2P has hydrogen bond interactions with Wat85 and (OG1)-Thr134. O3P is in hydrogen bond distance to (OG)Ser137 and (N)Ser137. O3 of L-DIAB is in hydrogen bond interactions with Wat77 and (OD2)Asp129. O4 is hydrogen bonded to Wat41 and (OD1)Asp130. The nitrogen atom N1 of the iminoaltritol ring has hydrogen bond interactions with Wat19 (Figure 5). In the L-DIAB structure O4P, O5P, and O6P of L-DIAB do not make favorable hydrogen bond interactions with ScAPRT (Figure 5).

The distance between the reactive N9 of adenine (or C9 in 9-deazaadenine) and the carbons of D-DIAB and L-DIAB corresponding to the reactive anomeric carbon of PRPP are an index of the inhibitor fit at the catalytic site. ScAPRT complexes with adenine and D-DIAB or L-DIAB can be compared with human (PDB ID: 1ZN7) and Giardia lamblia APRTase (PDB ID: 1L1R) in complexes with adenine (or 9-deazaadenine) and PRPP. The adenine binding mode is similar in all the APRTase structures. In human APRTase, the distance between N9 of adenine and reactive C1′ of PRPP is 3.7 Å. This distance is within experimental uncertainty in the structure of adenine with D-DIAB in ScAPRT (3.8 Å). With 9-deazaadenine and PRPP in G. lamblia APRT, the distance is 3.4 Å; closer, presumably due to the transition state character of 9-deazaadenine. However, when adenine and L-DIAB are bound to ScAPRT, the ring pucker of the complex adjusts to the unfavorable configuration, causing the carbon corresponding to the anomeric carbon of bound L-DIAB structures to be 4.4 Å from the anomeric carbon position. The carbons corresponding to the anomeric carbon (C1) of PRPP correspond to C2 and C5 of D-DIAB and L-DIAB, respectively (Scheme 1; Figure 4).

Crystal soaks with the DIAB isomers and adenine reveal the adenine binding pocket adjacent to D-DIAB (only in chain-A) and L-DIAB (only in chain-B). With D-DIAB, the adenine ring is sandwiched between the hydrophobic side chains of Phe27 and Ile131. The exocyclic N6 amino group is interacting with the peptide bond carbonyl of Leu26 and Wat14, while the N7 interacts with Wat191. The N7-Wat191 interaction is proposed to activate the N9 of adenine for attack of C1′ on PRPP in catalysis. In the Giardia lamblia APRT, N7 protonation for the N9 activation role is proposed to be due to a catalytic site Glu100.49 Similar interactions are also observed in the ScAPRT complex with L-DIAB (Figure 5). Adenine binds to only one of the two subunits, leaving the adjacent adenine-free binding pockets occupied by a symmetry-related Tyr107 side chain, suggesting subunit-sequential catalytic site activity.

Structural Basis of ScAPRT Inhibition.

Although D-DIAB and L-DIAB bind to give similar interactions at the active site of ScAPRT, L- and D-DIAB bind in reverse orientations with respect to the ScAPRT active site. The configuration of the 2′, 3′, 4′, and 5′ carbons differs for the inhibitors, causing the iminoaltritol ring to bind differently (Figure 5). Kinetic inhibition assays gave Ki values of 8.7 ± 1.5 μM and 14.9 ± 2.9 μM, respectively, for D-DIAB and L-DIAB, despite the different binding modes. Interactions of D-DIAB to the active site of ScAPRT are slightly more favorable than L-DIAB. The N1, O4P, O5P, and O6P of L-DIAB are not in hydrogen bond interactions, a possible explanation for the weaker binding of L-DIAB.

Structural Comparisons.

The crystal structure of native unliganded (PDB ID: 1G2Q) and sulfate-bound structures (PDB ID: 1G2P) are known.45 When compared to the unliganded ScAPRT structure (1G2Q), loop II (105−108) of the inhibitor bound structures is moved 5.8 Å toward the active site. A mutation in this loop (e.g., E106L) decreased kcat by 105; therefore, motion of loop II toward the active site is forming the catalytically competent structure.45 Loop II is disordered in the sulfate-bound structure (1G2P; Figures 3 and S2). The loop between β1 and β2 (loop I) of the hood domain retracts 1.5 Å, and its position is distinct from the catalytic site. The loop from residues 160−168 (loop III) has an open conformation in the inhibitor bound (5VJN and 5VJP) and in the sulfate-bound structures (1G2P), whereas this loop has a closed conformation in the unliganded structure (1G2Q). Loop III is moved 7.8 Å away from the active site in D-DIAB, L-DIAB, and sulfate bound structures (Figures 3 and S2). These structural changes indicate that loops II and III are important in catalytic site organization.

3. CONCLUSIONS

We have highlighted the synthetic utility and flexibility of the nitrone-redox methodology with iminosugars to form informative inhibitors for phosphoribosyltransferases. The redox methodology is particularly effective in the rigid, bicyclic system with the isopropylidene protecting group in place, which allows completely stereoselective hydride reductions of the nitrone group and imparts additional stability.35 As such, the commonly utilized iminoribitol 7– with a defined initial configuration–has led, with a careful choice of redox and nucleophilic addition strategies, to three different stereoisomers (2a, 15, and 24) of a selectively monoprotected diol. Two of these diastereoisomers (15 and 24) were elaborated to bis-phosphates D-DIAB and L-DAIB, which were shown to display weak inhibition of human OPRT, significant binding to PfOPRT, and substantial inhibition of ScAPRT. The crystal structure of D-DIAB and L-DIAB bound ScAPRT structures shows that both inhibitors bind to the enzyme active site with favorable enzyme−inhibitor interactions. We have also described significant improvements to the previously published synthesis of alcohol 2a,22,23 an intermediate utilized to prepare numerous transition-state analogue inhibitors.17 In addition, compound 3–an unusual vinyl-nitrone species has demonstrated functional utility as a trans-hydroxymethyl synthon in the stereoselective addition to nitrone 6a.

METHODS

Recombinant Protein Expression and Purification.

Recombinant N-terminal 6× His-tagged ScAPRT was expressed and purified as previously described,45 to >95% purity with modifications (see SI).

ScAPRT Inhibition Assays.

Enzyme activity assays for ScAPRT were performed at 25 °C in 50 mM HEPES at pH 7.5 in 250 μL total reaction volumes, and each individual initial rate was the average of triplicate measurements. Reaction mixtures contained 2 mM MgCl2, 250 μM 2,6-diaminopurine (2,6-DAP, a fluorescent and easily quantitated product),46 250 μM PRPP, and 1 mM DTT and were initiated by the addition of ScAPRT (100 nM). DAP consumption was monitored by a change in fluorescence (Ex: 280 nm/Em: 345 nm) over the course of 1 h using a SpectraMax M5 plate reader (Molecular Devices), at variable concentrations of either D-DIAB or L-DIAB (0− 200 μM). Inhibition data for bis-phosphates D-DIAB and L-DIAB with OPRTs contained 500 μM orotidine 5′-monophosphate, 50 mM Tris-HCl, at pH 8.0, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM pyrophosphate, and 25 nM PfOPRT or 200 nM HsOPRT at 25 °C. Reaction rates were monitored at 266 nm. Initial reaction rates (triplicate) were used to calculate the Ki values.

Crystallographic Inhibitor Binding and Structure Determination.

ScAPRT was used for the crystallographic inhibitor binding studies with D-DIAB and L-DIAB. Protein (10 mg mL−1) was incubated with 2 equiv of D-DIAB and L-DIAB separately for 2 h on ice. The cocrystallization of the incubated protein−ligand mixtures was then screened by the sitting drop vapor diffusion crystallization method at 22 °C using the Microlytic (MCSG1−4) crystallization conditions as described in the SI, Table S1. The X-ray diffraction data collection, data processing, structure determination, refinement, and structure analysis are detailed in the SI.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by research grants from the New Zealand government (C08 × 0701) and the National Institutes of Health research grants GM41916 and AI127807. The Einstein Crystallographic Core X-ray diffraction facility is supported by NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant S10 OD020068, which we gratefully acknowledge. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02–06CH11357. Use of the Lilly Research Laboratories Collaborative Access Team (LRL-CAT) beamline at Sector 31 of the Advanced Photon Source was provided by Eli Lilly Company, which operates the facility. Y. Zhang and R. G. Silva are acknowledged for the enzyme preparations.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00601.

Enzyme preparation, crystallization, and structure determination; crystallization and crystal handling; crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics; structural folds of ScAPRTs; superimposition of ScAPRT complexes; and supplementary results and discussion; experimental section for chemical syntheses; NMR spectra for synthetic compounds (PDF)

Accession Codes

The coordinates and structure factors are deposited at the Protein Data Bank with codes 5VJN and 5VJP.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Hove-Jensen B, Andersen KR, Kilstrup M, Martinussen J, Switzer RL, and Willemoës M (2017) Phosphoribosyl diphosphate (PRPP): biosynthesis, enzymology, utilization, and metabolic significance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 81, e00040–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Tao W, Grubmeyer C, and Blanchard JS (1996) Transition state structure of Salmonella typhimurium orotate phosphoribosyl-transferase. Biochemistry 35, 14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Zhang Y, Luo M, and Schramm VL (2009) Transition states of Plasmodium falciparum and human orotate phosphoribosyltransferases. J. Am. Chem. Soc 131, 4685–4694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Burgos ES, Vetticatt MJ, and Schramm VL (2013) Recycling nicotinamide. The transition-state structure of human nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 135, 3485–3493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Zhang Y, Evans GB, Clinch K, Crump DR, Harris LD, Fröhlich RF, Tyler PC, Hazleton KZ, Cassera MB, and Schramm VL (2013) Transition state analogues of Plasmodium falciparum and human orotate phosphoribosyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem 288, 34746–34754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Li CM, Tyler PC, Furneaux RH, Kicska G, Xu Y, Grubmeyer C, Girvin ME, and Schramm VL (1999) Transition-state analogs as inhibitors of human and malarial hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferases. Nat. Struct. Biol 6, 582–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Shi W, Li CM, Tyler PC, Furneaux RH, Grubmeyer C, Schramm VL, and Almo SC (1999) The 2.0 Å structure of human hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase in complex with a transition-state analog inhibitor. Nat. Struct. Biol 6, 588–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Abdo M, Zhang Y, Schramm VL, and Knapp S (2010) Electrophilic aromatic selenylation: new OPRT inhibitors. Org. Lett 12, 2982–2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Cardona F, Faggi E, Liguori F, Cacciarini M, and Goti A (2003) Total syntheses of hyacinthacine A 2 and 7-deoxycasuarine by cycloaddition to a carbohydrate derived nitrone. Tetrahedron Lett 44, 2315–2318. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Cardona F, Moreno G, Guarna F, Vogel P, Schuetz C, Merino P, and Goti A (2005) New concise total synthesis of (+)-lentiginosine and some structural analogues. J. Org. Chem 70, 6552–6555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Goti A, Cardona F, Brandi A, Picasso S, and Vogel P (1996) (1S, 2S, 7R, 8aS)-and (1S, 2S, 7S, 8aS)-trihydroxyoctahy-droindolizine: Two new glycosidase inhibitors by nitrone cycloaddition strategy. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 7, 1659–1674. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Goti A, Cicchi S, Mannucci V, Cardona F, Guarna F, Merino P, and Tejero T (2003) Iterative organometallic addition to chiral hydroxylated cyclic nitrones: Highly stereoselective syntheses of α, α′-and α, α-substituted hydroxypyrrolidines. Org. Lett 5, 4235–4238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Merino P, Delso I, Tejero T, Cardona F, Marradi M, Faggi E, Parmeggiani C, and Goti A (2008) Nucleophilic additions to cyclic nitrones en route to iminocyclitols−Total syntheses of DMDP, 6-deoxy-DMDP, DAB-1, CYB-3, nectrisine, and radicamine B. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2008, 2929–2947. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Tsou EL, Yeh YT, Liang PH, and Cheng WC (2009) A convenient approach toward the synthesis of enantiopure isomers of DMDP and ADMDP. Tetrahedron 65, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Argyropoulos NG, Panagiotidis TD, and Gallos JK (2006) Synthesis of enantiomerically pure hydroxylated pyrroline N-oxides from D-ribose. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 17, 829–836. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Cicchi S, Marradi M, Vogel P, and Goti A (2006) One-pot synthesis of cyclic nitrones and their conversion to pyrrolizidines: 7a-epi-crotanecine inhibits α-mannosidases. J. Org. Chem 71, 1614–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Schramm VL (2013) Transition states, analogues, and drug development. ACS Chem. Biol 8, 71–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Lassila JK, Zalatan JG, and Herschlag D (2011) Biological phosphoryl-transfer reactions: understanding mechanism and catalysis. Annu. Rev. Biochem 80, 669–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Witte JF, Bray KE, Thornburg CK, and McClard RW (2006) ‘Irreversible’slow-onset inhibition of orotate phosphoribosyl-transferase by an amidrazone phosphate transition-state mimic. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 16, 6112–6115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Asano N, Ikeda K, Yu L, Kato A, Takebayashi K, Adachi I, Kato I, Ouchi H, Takahata H, and Fleet GW (2005) The L-enantiomers of D-sugar-mimicking iminosugars are noncompetitive inhibitors of d-glycohydrolase? Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 16, 223–229. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Da Cruz FP, Newberry S, Jenkinson SF, Wormald MR, Butters TD, Alonzi DS, Nakagawa S, Becq F, Norez C, Nash RJ, Kato A, and Fleet GWJ (2011) 4-C-Me-DAB and 4-C-Me-LAB enantiomeric alkyl-branched pyrrolidine iminosugars are specific and potent α-glucosidase inhibitors; acetone as the sole protecting group. Tetrahedron Lett 52, 219–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Furneaux RH, Schramm VL, and Tyler PC (1999) Transition state analogue inhibitors of protozoan nucleoside hydrolases. Bioorg. Med. Chem 7, 2599–2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Evans GB, Furneaux RH, Hausler H, Larsen JS, and Tyler PC (2004) Imino-C-nucleoside synthesis: heteroaryl lithium carbanion additions to a carbohydrate cyclic imine and nitrone. J. Org. Chem 69, 2217–2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Oxley JC, Brady J, Wilson SA, and Smith JL (2012) The risk of mixing dilute hydrogen peroxide and acetone solutions. J. Chem. Health Saf 19, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Merino P, Revuelta J, Tejero T, Cicchi S, and Goti A (2004) Fully stereoselective nucleophilic addition to a novel chiral pyrroline N-oxide: Total syntheses of (2S, 3R)-3-hydroxy-3-methyl-proline and its (2R)-epimer. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2004, 776–782. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Delso I, Tejero T, Goti A, and Merino P (2011) Sequential nucleophilic addition/intramolecular cycloaddition to chiral non-racemic cyclic nitrones: A highly stereoselective approach to polyhydroxynortropane alkaloids. J. Org. Chem 76, 4139–4143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Li X, Qin Z, Wang R, Chen H, and Zhang P (2011) Stereoselective synthesis of novel C-azanucleoside analogues by microwave-assisted nucleophilic addition of sugar-derived cyclic nitrones. Tetrahedron 67, 1792–1798. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Marradi M, Cicchi S, Ignacio Delso J, Rosi L, Tejero T, Merino P, and Goti A (2005) Straightforward synthesis of enantiopure 2-aminomethyl and 2-hydroxymethyl pyrrolidines with complete stereocontrol. Tetrahedron Lett 46, 1287–1290. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Li YX, Huang MH, Yamashita Y, Kato A, Jia YM, Wang WB, Fleet GW, Nash RJ, and Yu CY (2011) L-DMDP, L-homoDMDP and their C-3 fluorinated derivatives: synthesis and glycosidase-inhibition. Org. Biomol. Chem 9, 3405–3414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Lombardo M, Fabbroni S, and Trombini C (2001) Entropy-controlled selectivity in the vinylation of a cyclic chiral nitrone. An efficient route to enantiopure polyhydroxylated pyrrolidines. J. Org. Chem 66, 1264–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Delso I, Marca E, Mannucci V, Tejero T, Goti A, and Merino P (2010) Tunable diastereoselection of biased rigid systems by Lewis acid induced conformational effects: Rationalization of the vinylation of cyclic nitrones en route to polyhydroxylated pyrrolidines. Chem. - Eur. J 16, 9910–9919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Bashor C, Denu JM, Brennan RG, and Ullman B (2002) Kinetic mechanism of adenine phosphoribosyltransferase from Leishmania donovani. Biochemistry 41, 4020–4031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Ducati RG, Breda A, Basso LA, and Santos DS (2011) Purine salvage pathway in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Curr. Med. Chem 18, 1258–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Ducati RG, Namanja-Magliano HA, and Schramm VL (2013) Transition-state inhibitors of purine salvage and other prospective enzyme targets in malaria. Future Med. Chem 5, 1341–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Goti A, and Nannelli L (1996) Synthesis of nitrones by methyltrioxorhenium catalyzed direct oxidation of secondary amines. Tetrahedron Lett 37, 6025–6028. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Murray RW, Iyanar K, Chen J, and Wearing JT (1996) Synthesis of nitrones using the methyltrioxorhenium/hydrogen peroxide system. J. Org. Chem 61, 8099–8102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Soldaini G (2004) Methyltrioxorhenium (MTO). Synlett, 1849–1850. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Saladino R, Neri V, Cardona F, and Goti A (2004) Oxidation of N,N-disubstituted hydroxylamines to nitrones with hydrogen peroxide catalyzed by polymer-supported methylrhenium trioxide systems. Adv. Synth. Catal 346, 639–647. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Schleiss J, Rollin P, and Tatibouët A (2010) Palladium-catalyzed coupling reactions of thioimidate N-oxides: Access to α-alkenyl-and α-aryl-functionalized cyclic nitrones. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 49, 577–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Buchlovič M, Man S, Kislitsõn K, Mathot C, and Potáček M (2010) One-pot, three-component synthesis of five-membered cyclic nitrones by addition/cyclization/condensation domino reaction. Tetrahedron 66, 1821–1826. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Huehls CB, Hood TS, and Yang J (2012) Diastereoselective synthesis of C3-quaternary indolenines using α, β-unsaturated N-aryl ketonitrones and activated alkynes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 51, 5110–5113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Sar CP, Jekő J, and Hideg K (2003) Synthesis of 2-alkenyl-1-pyrrolin-1-oxides and polysubstituted nitrones. Synthesis 2003, 1367–1372. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Kim HJ, Dogutan DK, Ptaszek M, and Lindsey JS (2007) Synthesis of hydrodipyrrins tailored for reactivity at the 1-and 9-positions. Tetrahedron 63, 37–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).McMurray JS, Coleman DR, Wang W, and Campbell ML (2001) The synthesis of phosphopeptides. Biopolymers 60, 3–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Shi W, Tanaka KS, Crother TR, Taylor MW, Almo SC, and Schramm VL (2001) Structural analysis of adenine phosphoribosyltransferase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry 40, 10800–10809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Firestone RS, Cameron SA, Tyler PC, Ducati RG, Spitz AZ, and Schramm VL (2016) Continuous fluorescence assays for reactions involving adenine. Anal. Chem 88, 11860–11867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Evans GB, Cameron SA, Luxenburger A, Guan R, Suarez J, Thomas K, Schramm VL, and Tyler PC (2015) Tight binding enantiomers of pre-clinical drug candidates. Bioorg. Med. Chem 23, 5326–5333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, and Read RJ (2007) Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr 40, 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Shi W, Sarver AE, Wang CC, Tanaka KS, Almo SC, and Schramm VL (2002) Closed site complexes of adenine phosphoribosyltransferase from Giardia lamblia reveal a mechanism of ribosyl migration. J. Biol. Chem 277, 39981–39988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.