Abstract

Lysosome function is compromised during aging and in many disease states. Interventions that promote lysosomal activity and acidification are thus of prime interest as treatments for longevity and health. Intracellular pH can be controlled by the exchange of protons for inorganic ions, and in cells from microbes to man, when potassium is restricted in the growth medium, the cytoplasm becomes acidified. Here we use a yeast model to show that potassium limited-cells exhibit hallmarks of increased acidity in the vacuole, the analog of the lysosome, and live long by a mechanism that requires the vacuolar machinery. The emerging picture is one in which potassium restriction shores up vacuolar acidity and function, conferring health benefits early in life and extending viability into old age. Against the backdrop of well-studied protein and carbohydrate restrictions that extend lifespan and healthspan, our work establishes a novel pro-longevity paradigm of inorganic nutrient limitation.

Keywords: Nutrient restriction, potassium, vacuole, acidification, yeast, lifespan

1. Introduction

The lysosome is the recycling hub of the eukaryotic cell. Its function is compromised in a number of human pathologies (Mizushima et al. 2008) and its breakdown is also considered a linchpin of aging (Cuervo 2008). Among the many possible failure modes of the autophagy-lysosomal system, a key role has emerged for the acidification of the lysosomal lumen, during disease (Colacurcio and Nixon 2016), and in otherwise healthy aging (Baxi et al. 2017; Hughes and Gottschling 2012). Interventions that correct these defects, boosting autophagic flux or otherwise maximizing the acidification or function of the lysosome, are of interest as therapies to promote health and longevity (Leeman et al. 2018; Shoji-Kawata et al. 2013).

A highly conserved mechanism for the control of intracellular pH is the exchange of protons for inorganic ions across a membrane. Potassium has been well studied for its function in this fundamental cell-biological process (Kaplan 2002). Intriguingly, in vitro culture conditions with reduced potassium evoke a drop in cytoplasmic pH, in cells from yeast to human (Adler, Zett, and Anderson 1972; Ramos, Haro, and Rodriguez-Navarro 1990; Wang, Geibel, and Giebisch 1993). Whether such acidification effects could modulate aging and health has been unexplored. Decades of work in the field have made clear that restrictions to the diet can slow disease and extend lifespan (Simpson et al., 2017); however, aging biologists have primarily focused on the longevity benefits of limiting protein or carbohydrate intake (Solon-Biet et al., 2015). We know little about the potential advantages of restricting other micronutrients in the diet, in part because the literature has centered on extreme starvation or toxicity regimes (Lee, Hwang, Artan, Jeong, & Lee, 2015).

In this work, we thus set out to test for health and longevity benefits of organellar acidification through modest potassium restriction, using yeast as a model. As potassium-chelating drugs are in current clinical use (Kovesdy, 2014; Vu, De Castro, Shottland, Frishman, & Cheng-Lai, 2016), we used one such compound, alongside media and genetic manipulations, to evaluate the impact of potassium limitation and investigate its mechanism. Our results revealed that potassium restriction acidified the vacuole, the yeast degradation and storage organelle, and robustly extended yeast lifespan, by a mechanism dependent on vacuolar components.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Yeast strains and media

BY4742 (MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0) served as the wild-type strain. Isogenic strains bearing deletions of TRK1, TRK2, VPH1, AVT1 or ATG7 were from the yeast knockout collection (Dharmacon). To construct the isogenic strain overexpressing AVT1, we introduced a copy of AVT1 under the GPD1 promoter into a region of chromosome I using the pAG306-GPD-AVT1 chr I plasmid (a kind gift from Adam Hughes) as described (Hughes and Gottschling 2012). Compositions of all media used in this study are listed in Table S1. Low-K medium and its synthetic complete control, which we call standard medium, had potassium concentrations of 2 mM and 9 mM respectively (Fig. S1A); translucent K-free medium (Navarrete et al. 2010) had a basal concentration of 0.5 mM potassium (Fig. S1A), to which we added potassium chloride to achieve 1 mM or 10 mM potassium as indicated in Fig. S3. Growth rates were tabulated from OD600 of mid-log cultures measured in a 3-4 h window before loading the microfluidic device for lifespan assays (see section 2.3) and are reported as the mean of 3-8 independent biological replicates as follows: wild-type, 1.54h in control medium and 1.78h in low-K, p < 0.001; vph1, 2.08h in control and 2.31h in low-K, p < 0.01 ; AVT1OE, 1.60h in control and 1.73h in low-K, p < 0.1; and avt1, 2.00h in control and 2.68h in low-K, p < 0.001, with significances estimated using a two-tailed t-test. For yeast lifespan assays involving sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS, Sigma-Aldrich), SPS was added to the control medium to achieve a final concentration of 5 mM. For quinacrine staining, overnight log phase cultures were diluted and allowed to grow in log phase for 6.5 hours before harvesting. For Fig. 1B, these cultures were incubated with 500 nM of concanamycin A (ConcA, Tocris Bioscience) for 30 minutes before harvesting.

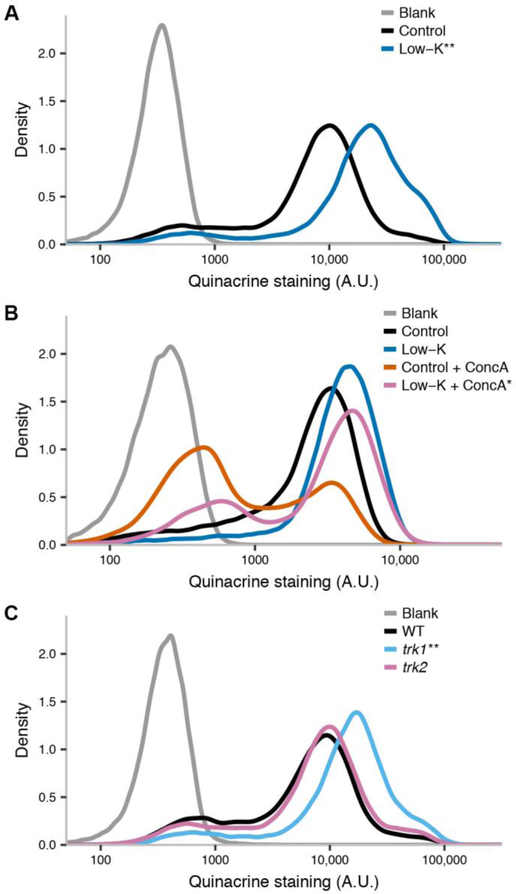

Figure 1. Potassium restriction evokes vacuolar acidification and confers resistance to V-ATPase inhibition.

In each panel, the y-axis reports the proportion of yeast cells stained by the vacuolar dye quinacrine with the intensity (in arbitrary units) shown on the x. Blank, no quinacrine. (A) Wild-type yeast cultured in standard medium (control) or potassium restricted medium (low-K). (B) Data are as in (A) except that after growth in low-K or control medium, cells were subject to acute treatment with concanamycin A (ConcA) or left untreated. (C) Wild-type (WT) or isogenic potassium transporter mutants (trk1, trk2) cultured in standard potassium-replete medium. **, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.02 in a comparison of the indicated sample to cells cultured in control medium (A), cells cultured in control medium and then treated with concanamycin A (B), or wild-type cells (C).

2.2. Yeast quinacrine staining

A 0.5 OD600 equivalent of cells in mid-log phase was washed once in media with 100 mM HEPES pH 7.6, and resuspended in 100 μL of the same buffered media. Quinacrine (Weisman, Bacallao, and Wickner 1987) was added to a final concentration of 200 μM; the suspension was incubated for 10 minutes at 30°C and then 5 minutes on ice. The cells were then washed with ice-cold 100 mM HEPES pH 7.6 with 2% glucose and re-suspended in the same buffer. To quantify quinacrine intensity by flow cytometry, the suspension was analyzed using a BD LSRII benchtop flow cytometer with excitation at 405 nm and emission collected using a 525/50 nm filter set. We refer to the pipeline from growth through staining and quantification as a replicate, with a given such experiment done using different media or strains in parallel; at least five such independent replicates were performed for each strain and/or condition, alongside a wild-type culture in the control medium to which quinacrine was not administered, which served as the blank. To evaluate statistical significance in Figs. 1A, 1C, S3A, and S4A, in each replicate we first tabulated the geometric mean intensity across cells in the treatment of interest and in the appropriate control, and we then took the ratio of these two intensities; we collated such ratios across all replicates, and tested whether the mean of their distribution was significantly different from 1 using a one-tailed one-sample t-test. To quantify the effect of ConcA in Fig. 1B, we first tabulated the mean m and standard deviation s of the blank population from each experimental replicate. For each cell of a given culture (pre-cultured in low-K or control medium, and treated acutely with ConcA or untreated), we first classified the target cell as stained if its signal intensity had a value >3s above m and unstained otherwise. We next calculated the proportion p of cells stained according to this metric. We then normalized the value of p from ConcA-treated cells against the analogous value from untreated cells in the respective replicate; we call this ratio r, a normalized report of the impact of ConcA treatment. We then tested whether, across replicates, r differed between cultures grown in low-K and control media using a one-tailed paired t-test. To quantify quinacrine intensity by microscopy in Fig. S2, after culture, staining, and wash as above, cells were transferred to 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-One) coated with concanavalin A (Sigma-Aldrich), and imaged within 15 minutes under 60X oil magnification using a Nikon Eclipse Ti-E with appropriate filter sets. Images were analyzed using the Image Analyst MKII image processing software; we identified as a mother any cell with an attached bud that was at least 70% of its size, and we quantified quinacrine staining as the average pixel intensity of each such cell. A given medium or strain was subjected to at least four replicates, with 60-200 cells analyzed per replicate. To test for statistical significance, we tabulated the mean intensity per replicate for each sample, and compared the set of such means between the treatment of interest and the appropriate control using a one-tailed paired t-test.

2.3. Yeast microfluidic lifespan assay.

Microfluidic devices were fabricated as described (Zhang et al. 2012), except that the final chip was sealed to epoxysilane coated glass slides (Microsurfaces, Inc) overnight at 90°C. Channels in the microfluidic device were washed for an hour with 1% BSA and then an hour with media before loading cells. To prepare cells for loading, overnight yeast cultures in log phase were diluted to an OD600 of 0.04-0.08 into 50 mL, allowed to grow to an OD600 of 0.5-0.8, and concentrated to an OD600 of approximately 30. 30-50 μL of this suspension was loaded into the device by a syringe connected to a pump, followed by media wash for the duration of the experiment (90 hours). Time-lapse microscopy was done using a Nikon Eclipse Ti-E under 40X magnification, with bright-field images taken at each location every 15 minutes. The number of divisions for each mother cell was counted manually and individually. Cells that were washed out before death were incorporated into the lifespan curve as right-censored data using Kaplan-Meier analysis. The pipeline from growth through loading and quantification of division counts was repeated at least three times for each strain and/or condition for each lifespan experiment, with 80-130 cells per replicate, unless otherwise stated. Median lifespans and confidence intervals were estimated in R using the survival package. Significance of lifespan differences between conditions/strains was evaluated by the Cox proportional hazards test. To test the significance of interaction between potassium restriction and genotype, or potassium restriction and chelator treatment, we used the multivariate Cox proportional hazards test.

2.4. Elemental analysis.

To quantify total metal content in yeast, we first cultured cells in a given medium to mid-log phase, from which ~10 OD600 equivalents were pelleted by centrifugation and washed in DI water. Each pellet was dried overnight at 60°C and dry weight was quantified as the average of two measurements on a microbalance (yielding weight measurements of 2-3 mg). The sample was digested overnight in 250 μL of OmniTrace 70% HNO3 (MilliporeSigma) and diluted with OmniTrace water (MilliporeSigma) to 5% HNO3. Metal abundance was measured by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrophotometry (ICP-OES) using a 5100 SVDV ICP-OES (Agilent Technologies) calibrated with National Institute of Standards and Technology-traceable elemental standards. Instrument precision for each element was typically between 5–10%. Cesium (50 ppm) was used for ionization suppression and yttrium (5 ppm) was used as an internal standard. All reagents and plasticware were certified or tested for metal contamination. We refer to the pipeline from growth and drying through ICP-OES measurement as a replicate; two such replicates were carried out for each strain and/or condition. To quantify total metal content in unused yeast medium, 100 μL samples in triplicate were taken from a well-mixed solution and subjected to drying and ICP-OES as above. Elemental content data was summarized using ICP Expert (Agilent Technologies) and normalized to dry weight for analysis of yeast pellets, and to volume for analysis of media.

3. Results

We first hypothesized that the acidification of the yeast cytoplasm in low-potassium conditions (Young et al. 2010; Ramos, Haro, and Rodriguez-Navarro 1990) could have a knock-on effect on the pH of the vacuole, the yeast organelle analogous to the lysosome. To explore this, we formulated a synthetic yeast growth medium with reduced potassium (low-K medium; Table S1), and used elemental analysis to confirm the drop in K+ concentration in this medium relative to the standard (Fig. S1A). We cultured yeast cells in this low-K medium and stained them with quinacrine, a fluorescent dye used as a vacuolar pH indicator owing to its accumulation in acidic compartments. Flow-cytometric analysis revealed a 2.5 fold-increase in quinacrine staining in low-K treated cells relative to the replete control (Fig. 1A). This trend was confirmed by quantification of the localized staining of vacuoles in microscopy images (Fig. S2), and also could be recapitulated by a distinct formulation of potassium-restricted medium (modified translucent K+-free medium (Navarrete et al. 2010); Table S1 and Fig. S3A). If the increased quinacrine staining upon long-term growth in low-K conditions reflected a bona fide boost in vacuolar acidity, we expected cells grown in this medium to be resistant to blockade of the vacuolar V-ATPase pump, which maintains the pH of the yeast vacuole. Consistent with this prediction, low-K treatment conferred a 37% improvement in protection against the V-ATPase blocker concanamycin A in an acute scenario (Fig. 1B). Control experiments ruled out other manipulations in low-K medium as drivers of the increased quinacrine signal (Fig. S4A), further supporting the inference that potassium restriction was the proximal cause for the staining patterns we observed in these restricted media.

To investigate further the relationship between potassium and the vacuolar environment, we turned to a genetic approach: we hypothesized that compromising potassium transport would lead to low pH in vacuoles even during culture in potassium-replete medium. Conforming to this expectation, a strain harboring a mutation in the transporter TRK1, whose striking growth and metabolic phenotypes have been previously reported (Madrid et al. 1998), exhibited a 2.2-fold increase in quinacrine staining compared to wild-type cells (Fig. 1B). No change in vacuolar staining could be detected for a trk2 mutant (Fig. 1B), consistent with its weak growth phenotypes (Madrid et al. 1998). Together, these findings suggest that potassium restriction, by environmental or genetic means, promotes vacuolar acidity in yeast.

Under standard conditions, yeast vacuolar pH rises with age. Lifespan can be extended by mutations that correct this defect, either by enhancing proton import into the vacuole or by limiting proton efflux at the cell surface (Hughes and Gottschling 2012). We thus reasoned that if potassium restriction were boosting vacuolar acidity in yeast, it might also confer longevity. Indeed, in replicative lifespan assays, yeast cultured in low-K medium exhibited a 20% lifespan extension relative to cells in standard medium (Fig. 2A); cells cultured in translucent K+-free medium also lived markedly longer than controls (Fig. S3B). These two potassium-restricted media formulations differed with respect to several other ionic components (see Table S1), arguing strongly in favor of limiting potassium itself as the proximate cause of lifespan extension in both cases. Specific control experiments ruled out excess sodium as a prolongevity manipulation (Fig. S4B).

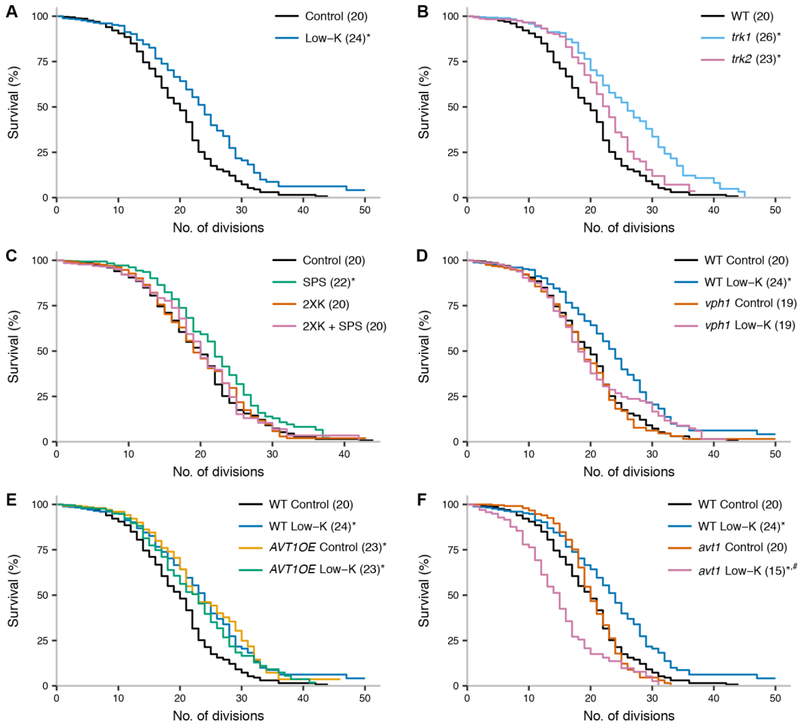

Figure 2. Potassium restriction extends yeast lifespan in a vacuole-dependent manner.

In each trace, the y-axis reports the proportion of yeast mother cells that produced at least the number of daughter cells on the x; the number in parentheses reports the median lifespan, in number of divisions, across biological replicates of the indicated genotype in standard medium (control) and/or treatment. Confidence intervals for lifespan measurements are reported in Table S2. (A) Wild-type cells cultured in the indicated medium. Control, standard medium; low-K, potassium restricted medium. (B) Strains isogenic to wild-type lacking the indicated potassium transporter. (C) Wild-type cells cultured in the indicated medium; 2XK, control medium with twice the potassium concentration of the standard; SPS, medium supplemented with 5 mM sodium polystyrene sulfonate. The impact of potassium restriction was significantly different between standard and 2XK media (p = 0.024). (D) vph1, a strain isogenic to the wild-type lacking VPH1, a component of the vacuolar H+ ATPase. The impact of potassium restriction was significantly different between wild-type and vph1 (p = 0.026). (E) AVT1OE, a strain isogenic to the wild-type overexpressing the vacuolar amino acid transporter AVT1. The impact of potassium restriction was significantly different between wild-type and AVT1OE (p= 9.5×10−5). (F) avt1, a strain isogenic to the wild-type lacking AVT1. The impact of potassium restriction was significantly different between wild-type and AVT1OE (p = 9.7×10−14). *, p < 0.001 in a comparison to wild-type in control medium. #, p < 0.001 in a comparison to avt1 in control medium.

Furthermore, as expected given our quinacrine staining results (Fig. 1C), the trk1 mutant exhibited a 30% longer lifespan than wild-type, in standard medium; the trk2 mutant was also slightly long-lived (Fig. 2B). We also found that yeast cultured with sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS), a cation chelator used to treat hyperkalemia (Scherr et al. 1961), had a modest but reproducible longevity phenotype, which was abrogated in the presence of excess potassium (Fig. 2C). High-potassium medium alone had no impact on lifespan (Fig. 2C), as expected given that yeast cells maintain potassium homeostasis in such conditions (Kahm et al. 2012). These data establish that limiting potassium extends yeast lifespan, with the strongest benefits accruing from low-K treatment and TRK1 inactivation.

To pursue the mechanism of the longevity effect of potassium restriction, we focused on our low-K growth paradigm. We hypothesized that the benefits of the latter could be mediated by the V-ATPase pump, and to test this notion, we focused on VPH1, a core component of the pump. As predicted, culture in low-K medium failed to extend the lifespan of the vph1 mutant (Fig. 2D). Separately, to test the role of vacuolar function in the longevity effect of low-K treatment, we manipulated the vacuolar amino acid transporter Avt1, a client of the vacuolar proton gradient that governs yeast lifespan (Hughes and Gottschling 2012). In a long-lived strain overexpressing AVT1, we detected no further extension of lifespan upon growth in low-K medium (Fig. 2E). Likewise, low-K treatment failed to induce longevity in an avt1 mutant, instead shortening lifespan (Fig. 2F); plausibly, the latter defect could be due to a toxic buildup of protons in the absence of Avt1 activity. We conclude that that the longevity benefit of potassium restriction we have observed in yeast requires wild-type levels and function of the V-ATPase pump and Avt1. Interestingly, potassium restriction effects were not detectably changed in a strain bearing a mutation in the autophagy regulator ATG7 (Fig. S5). This was particularly striking given the longevity of the ATG7 mutant in standard conditions (Fig. S5), consistent with the known replicative longevity of other autophagy mutants (McCormick et al. 2015), despite their defects in chronological aging assays (Alvers et al. 2009). These data indicate that the mechanism by which potassium restriction benefits yeast cells likely hinges on vacuolar activities other than macromolecular breakdown and recycling.

4. Discussion

Our work has shown that potassium-restricted cells exhibit hallmarks of increased vacuolar acidity, and are long-lived by a mechanism dependent on the vacuole. Our results are most consistent with a model in which as the yeast cytoplasmic pH becomes more acidic during potassium restriction (Ramos, Haro, and Rodriguez-Navarro 1990), the V-ATPase pumps excess protons into the vacuole, and this increased acidification shores up vacuolar function. Longevity would be a consequence of flux through this pathway throughout the life of the cell, dovetailing with other “early-life” interventions that extend yeast lifespan, including overexpression of vacuolar components (Arlia-Ciommo et al. 2014).

Our data leave open the question of exactly how chronic potassium limitation leads to a drop in cellular pH. Among the dramatic effects of acute potassium starvation (Lauff and Santa-Maria 2010) is the disruption of the potential at the cell membrane, which triggers avid proton efflux through the proton exporter Pma1 but also activation of carbonic anhydrase (Kahm et al. 2012); conceivably the latter could directly lead to chronic accumulation of protons inside the cell. As the treatments studied here do not perturb intracellular potassium itself (Fig. S1B), their effects likely are a product of metabolic remodeling that the cell undergoes to maintain potassium homeostasis. One intriguing possibility is that this could involve a hormetic response to the ammonium toxicity evoked by potassium restriction (Hess et al. 2006).

To date only a handful of interventions have been shown to acidify lysosomes in vivo, most notably a blocker of the DNA damage response regulator ATM (Kang et al. 2017) and an adenylate cyclase activator (Folts et al. 2016). Our findings highlight the potential for therapies that manipulate the control of pH by ion availability. In animal cells, the Na+/K+-ATPase pump regulates the sodium gradient at the plasma membrane, which in turn drives the Na+/H+ antiporter and thus cellular pH (Kaplan 2002). During potassium restriction, pump activity slows (Aronsen et al. 2014; Wang, Geibel, and Giebisch 1993) and cytoplasmic pH drops (Adler, Zett, and Anderson 1972; Wang, Geibel, and Giebisch 1993), raising the possibility that potassium restriction in these systems may have benefits that parallel those we have seen in yeast. It is tempting to speculate that the longevity effects in invertebrates of ouabain (Ashmore et al. 2009), a Na+/K+-ATPase blocker, may be mediated in part by an acidification mechanism. Future studies will establish whether and how potassium limitation, or manipulating pH control by related means, impacts lysosomal function, health, and longevity in metazoans.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Elemental analysis of media and yeast cells

Fig. S2. Potassium restriction in yeast enhances staining of the vacuolar pH indicator quinacrine, as measured by quantitative microscopy.

Fig. S3. In the context of a base of translucent K+-free medium, potassium restriction evokes increased staining by the vacuolar pH indicator quinacrine, and extends yeast lifespan

Fig. S4. Increasing sodium concentration in control medium does not affect vacuolar staining by the vacuolar pH indicator quinacrine or lifespan

Fig. S5. Potassium restriction extends yeast lifespan in an autophagy-independent manner.

Table S1. Media composition

Table S2. Confidence intervals on median lifespan measurements. Each row reports results across replicates of the indicated lifespan experiment. 0.95 UCL and 0.95 LCL denote the 95% upper and lower confidence intervals, respectively, on the median.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Adam Hughes for his generosity with experimental advice and yeast strains; Herbert Kasler, Akos Gerencser, Kathy Schultz, Austen McMahan, and Rylee Hackley for technical assistance; David Botstein, Dan Gottschling, Julie Andersen, Gordon Lithgow, Manish Chamoli, and Tyler Hilsabeck for helpful discussions; and Eric Verdin and Arnold Kahn for critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a fellowship from the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research to A.N.S., by National Institutes of Health R01 AG043080 to B.K.K. and R.B.B., and by R03 AG056938 and a Glenn Award for Research in Biological Mechanisms of Aging to R.B.B.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adler Sheldon, Zett Barbara, and Anderson Barbara. 1972. “The Effect of Acute Potassium Depletion on Muscle Cell PH in Vitro.” Kidney International 2 (3): 159–63. 10.1038/ki.1972.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvers Ashley L., Fishwick Laura K., Wood Michael S., Hu Doreen, Chung Hye S., Dunn William A. Jr, and Aris John P.. 2009. “Autophagy and Amino Acid Homeostasis Are Required for Chronological Longevity in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae.” Aging Cell 8 (4): 353–69. 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00469.X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlia-Ciommo Anthony, Piano Amanda, Leonov Anna, Svistkova Veronika, and Titorenko Vladimir I.. 2014. “Quasi-Programmed Aging of Budding Yeast: A Trade-off between Programmed Processes of Cell Proliferation, Differentiation, Stress Response, Survival and Death Defines Yeast Lifespan.” Cell Cycle 13 (21): 3336–49. 10.4161/15384101.2014.965063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronsen JM, Skogestad J, Lewalle A, Louch WE, Hougen K, Stokke MK, Swift F, et al. 2014. “Hypokalaemia Induces Ca2+ Overload and Ca2+ Waves in Ventricular Myocytes by Reducing Na+,K+-ATPase A2 Activity.” The Journal of Physiology 593 (6): 1509–21. 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.279893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore Lesley J., Hrizo Stacy L., Paul Sarah M., Van Voorhies Wayne A., Beitel Greg J., and Palladino Michael J.. 2009. “Novel Mutations Affecting the Na, K ATPase Alpha Model Complex Neurological Diseases and Implicate the Sodium Pump in Increased Longevity.” Human Genetics 126 (3): 431–47. 10.1007/s00439-009-0673-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxi Kunal, Ghavidel Ata, Waddell Brandon, Harkness Troy A., and de Carvalho Carlos E.. 2017. “Regulation of Lysosomal Function by the DAF-16 Forkhead Transcription Factor Couples Reproduction to Aging in Caenorhabditis Elegans.” Genetics 207 (1): 83–101. 10.1534/genetics.117.204222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colacurcio Daniel J., and Nixon Ralph A.. 2016. “Disorders of Lysosomal Acidification-The Emerging Role of v-ATPase in Aging and Neurodegenerative Disease.” Ageing Research Reviews, Lysosomes in Aging, 32 (December): 75–88. 10.1016/j.arr.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo Ana Maria. 2008. “Autophagy and Aging: Keeping That Old Broom Working.” Trends in Genetics 24 (12): 604–12. 10.1016/j.tig.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folts Christopher J., Nicole Scott-Hewitt Christoph Proschel, Margot Mayer-Pröschel, and Mark Noble. 2016. “Lysosomal Re-Acidification Prevents Lysosphingolipid-Induced Lysosomal Impairment and Cellular Toxicity.” PLOS Biology 14 (12): e1002583 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess David C., Lu Wenyun, Rabinowitz Joshua D., and Botstein David. 2006. “Ammonium Toxicity and Potassium Limitation in Yeast.” PLoS Biology 4 (11): e351 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes Adam L., and Gottschling Daniel E.. 2012. “An Early Age Increase in Vacuolar PH Limits Mitochondrial Function and Lifespan in Yeast.” Nature 492 (7428): 261–65. 10.1038/nature11654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahm Matthias, Navarrete Clara, Llopis-Torregrosa Vicent, Herrera Rito, Barreto Lina, Yenush Lynne, Ariño Joaquin, Ramos Jose, and Kschischo Maik. 2012. “Potassium Starvation in Yeast: Mechanisms of Homeostasis Revealed by Mathematical Modeling.” PLOS Computational Biology 8 (6): e1002548 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Hyun Tae, Joon Tae Park Kobong Choi, Kim Yongsub, Hyo Jei Claudia Choi, Chul Won Jung, Young-Sam Lee, and Park Sang Chul. 2017. “Chemical Screening Identifies ATM as a Target for Alleviating Senescence.” Nature Chemical Biology 13 (6): 616–23. 10.1038/nchembio.2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan Jack H. 2002. “Biochemistry of Na,K-ATPase.” Annual Review of Biochemistry 71 (1): 511–35. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.102201.141218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauff Diana Beatríz, and Santa-María Guillermo E.. 2010. “Potassium Deprivation Is Sufficient to Induce a Cell Death Program in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae.” FEMS Yeast Research 10 (5): 497–507. 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2010.00628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman Dena S., Hebestreit Katja, Ruetz Tyson, Webb Ashley E., McKay Andrew, Pollina Elizabeth A., Dulken Ben W., et al. 2018. “Lysosome Activation Clears Aggregates and Enhances Quiescent Neural Stem Cell Activation during Aging.” Science 359 (6381): 1277–83. 10.1126/science.aag3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrid Ricardo, Gómez María J., Ramos José, and Alonso Rodríguez-Navarro. 1998. “Ectopic Potassium Uptake in Trk1 Trk2 Mutants of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Correlates with a Highly Hyperpolarized Membrane Potential.” Journal of Biological Chemistry 273 (24): 14838–44. 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick Mark A., Delaney Joe R., Tsuchiya Mitsuhiro, Tsuchiyama Scott, Shemorry Anna, Sim Sylvia, Chou Annie Chia-Zong, et al. 2015. “A Comprehensive Analysis of Replicative Lifespan in 4,698 Single-Gene Deletion Strains Uncovers Conserved Mechanisms of Aging.” Cell Metabolism 22 (5): 895–906. 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima Noboru, Levine Beth, Cuervo Ana Maria, and Klionsky Daniel J.. 2008. “Autophagy Fights Disease through Cellular Self-Digestion.” Nature 451 (7182): 1069–75. 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete Clara, Petrezsélyová Silvia, Barreto Lina, Martínez José L., Zahrádka Jaromír, Ariño Joaquín, Sychrová Hana, and Ramos José. 2010. “Lack of Main K+ Uptake Systems in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Cells Affects Yeast Performance in Both Potassium-Sufficient and Potassium-Limiting Conditions.” FEMS Yeast Research 10 (5): 508–17. 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2010.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos José, Haro Rosario, and Rodriguez-Navarro Alonso. 1990. “Regulation of Potassium Fluxes in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae.” Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta 1029 (2): 211–17. 10.1016/0005-2736(90)90156-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherr Lawrence, Ogden David A., Mead Allen W., Spritz Norton, and Rubin Albert L.. 1961. “Management of Hyperkalemia with a Cation-Exchange Resin.” New England Journal of Medicine 264 (3): 115–19. 10.1056/NEJM196101192640303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji-Kawata Sanae, Sumpter Rhea, Leveno Matthew, Campbell Grant R., Zou Zhongju, Kinch Lisa, Wilkins Angela D., et al. 2013. “Identification of a Candidate Therapeutic Autophagy-lnducing Peptide.” Nature 494 (7436): 201–6. 10.1038/nature11866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WH, Geibel J, and Giebisch G. 1993. “Mechanism of Apical K+ Channel Modulation in Principal Renal Tubule Cells. Effect of Inhibition of Basolateral Na(+)-K(+)-ATPase.” The Journal of General Physiology 101 (5): 673–94. 10.1085/jgp.101.5.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman LS, Bacallao R, and Wickner W. 1987. “Multiple Methods of Visualizing the Yeast Vacuole Permit Evaluation of Its Morphology and Inheritance during the Cell Cycle.” The Journal of Cell Biology 105 (4): 1539–47. 10.1083/jcb.105.4.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young Barry P., Shin John J. H., Orij Rick, Chao Jesse T., Shu Chen Li, Guan Xue Li, Khong Anthony, et al. 2010. “Phosphatidic Acid Is a PH Biosensor That Links Membrane Biogenesis to Metabolism.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 329 (5995): 1085–88. 10.1126/science.1191026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Yi, Luo Chunxiong, Zou Ke, Xie Zhengwei, Brandman Onn, Ouyang Qi, and Li Hao. 2012. “Single Cell Analysis of Yeast Replicative Aging Using a New Generation of Microfluidic Device.” PLOS ONE 7 (11): e48275 10.1371/journal.pone.0048275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Elemental analysis of media and yeast cells

Fig. S2. Potassium restriction in yeast enhances staining of the vacuolar pH indicator quinacrine, as measured by quantitative microscopy.

Fig. S3. In the context of a base of translucent K+-free medium, potassium restriction evokes increased staining by the vacuolar pH indicator quinacrine, and extends yeast lifespan

Fig. S4. Increasing sodium concentration in control medium does not affect vacuolar staining by the vacuolar pH indicator quinacrine or lifespan

Fig. S5. Potassium restriction extends yeast lifespan in an autophagy-independent manner.

Table S1. Media composition

Table S2. Confidence intervals on median lifespan measurements. Each row reports results across replicates of the indicated lifespan experiment. 0.95 UCL and 0.95 LCL denote the 95% upper and lower confidence intervals, respectively, on the median.