Abstract

Voltage-gated sodium channels respond to excitatory inputs in nerve cells, generating spikes of depolarization at axon hillock regions and propagating the initial rising phase of action potentials through axons. It previously has been shown that protein kinase A (PKA) attenuates sodium current amplitude 20–50% by phosphorylating serines located in the I–II linker of the sodium channel. We have tested the individual contributions of five PKA consensus sites in the I–II linker by measuring sodium currents expressed in Xenopusoocytes during conditions of PKA induction. PKA was induced by perfusing oocytes with a cocktail that contained forskolin, chlorophenylthio-cAMP, dibutyryl-cAMP, and 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine. Phosphorylation at the second PKA site (serine-573) was necessary and sufficient to diminish sodium current amplitude. Phosphorylation at the third and fourth positions (serine-610 and serine-623) reduced current amplitude, but the effect was considerably smaller at those positions. Introduction of a negative charge at site 2 by substitution of serine-573 with an aspartate constitutively reduced the basal level of sodium current, indicating that the attenuation of sodium current by phosphorylation of site 2 by PKA results from the introduction of a negative charge at this site.

Keywords: ion channel, modulation, cAMP, site-directed mutagenesis, sodium channel, phosphorylation, protein kinase A, Xenopusoocytes, forskolin

Voltage-gated sodium channels play a key role in the transmission of signals through electrically excitable cells. If the spatial summation of excitatory and inhibitory inputs exceeds a threshold level of membrane depolarization, sodium channels that are localized at high density in the axon hillock region of nerve cells are activated, resulting in initiation of an action potential. Therefore, one mechanism by which electrical excitability can be regulated is by altering the activity of sodium channels.

Phosphorylation by protein kinase A (PKA) is a common regulatory mechanism that is observed for a large number of proteins. In the case of the voltage-gated rat brain sodium channel, PKA phosphorylation modifies channel function by reducing the peak current amplitude but without affecting sodium current kinetics or the voltage dependence of conductance or inactivation (Gershon et al., 1992; Li et al., 1992;Schiffmann et al., 1995; Smith and Goldin, 1996). When purified PKA was applied to patches that were excised from transfected Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, sodium current magnitude was reduced by 40–50%, resulting from a decrease in the open probability of the channels (Li et al., 1992). Similarly, when the sodium channel was expressed inXenopus oocytes, PKA induction either by forskolin or by isoproterenol stimulation of a coexpressed β2-adrenergic receptor reduced current amplitude by 20–30% (Gershon et al., 1992;Smith and Goldin, 1996). All other electrophysiological properties of the channel were unchanged. Finally, when PKA was induced in cultured striatal neurons from neonatal rats by treatment with the dopamine D1 receptor agonist SKF38393, peak sodium current amplitude was reduced reversibly by 38% (Schiffmann et al., 1995). The decrease was blocked by pretreatment of the cells with protein kinase inhibitor, a specific inhibitor of PKA, demonstrating the involvement of PKA. The excitability of the treated neurons also was reduced, as evidenced by an elevated threshold for the generation of action potentials.

The sodium channel from rat brain is a substrate for phosphorylation by PKA (Costa et al., 1982; Costa and Catterall, 1984; Rossie and Catterall, 1987), and that phosphorylation is restricted to PKA consensus sites located in the cytoplasmic linker that connects domains I and II of the channel (Rossie et al., 1987; Rossie and Catterall, 1989; Murphy et al., 1993). We have shown previously that the attenuation of sodium current by PKA requires specific phosphorylation at these sites (Smith and Goldin, 1996). When five PKA consensus sites in the I–II linker were eliminated either by deletion or by collective substitution of the serines with alanines, PKA-mediated attenuation of current amplitude was prevented. If aspartates were substituted at all five of the PKA sites to mimic the negative charge resulting from phosphorylation, sodium current amplitude was reduced constitutively, suggesting that the reduction of current by phosphorylation is caused by the introduction of negative charge(s) at one or more of the sites.

In this report we demonstrate that the second PKA site in the I–II linker (containing serine-573) is both necessary and sufficient for PKA current attenuation. Replacement of serine-573 with an aspartate resulted in a channel that expressed a constitutively reduced level of current. We also show that phosphorylation at sites 3 and 4 reduced current amplitude but to a lesser extent than did phosphorylation at site 2. These results indicate that phosphorylation reduces sodium current amplitude primarily by introducing a negative charge at serine-573.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Site-directed mutagenesis

The plasmid pVA2580 contains the rat brain IIA (RIIA) sodium channel coding region downstream from a T7 RNA polymerase promoter (Auld et al., 1990). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed either by M13 mutagenesis or by PCR. Each of the mutations was confirmed by DNA sequencing to confirm the engineered changes and to rule out other mutations caused by polymerase error.

M13 mutagenesis. The I–II linker region of RIIA, as defined by the unique Tth111I and SphI restriction sites in pVA2580, was subcloned into mp18A, a version of mp18 with a polylinker region that was modified to contain unique restriction sites in the RIIA coding region. M13 single-strand mutagenesis was used to create mutations, as previously described (Smith and Goldin, 1996). The FLAG epitope (Hopp et al., 1988) was incorporated into the N terminus of the sodium channel, using M13 loop-in insertion mutagenesis. The following oligonucleotides were used for mutagenesis:S554(A/D)-S555(A/D), GACTGGTGCGGA(G/T) CG(G/T)CAAATCTCTTCTC; S573(A/D), AGGCTTGCTCTA(C/T) CGTTGCGTCTT; S610(A/D), GGTACAAATAGA(G/T)CGTCTCTTCTG; S623(A/D), CCTGGCTGACATTG(G/T)CAGGACGCCTTTCTC;S686(A/D)-S687(A/D)-S688(A/D), GAGACGTGGTAA(G/T)CA(G/T)CG(G/T)CTCTCCTCTTCCT; and FLAG insertion, GACCGTGCTTTAT CGTCATCGTCTTTATAGTCCATTCTTTGTCGACG.

PCR mutagenesis. To generate mutant channels with single PKA sites present, we used the PKACOMP-A mutant as a starting PCR template. For each construct two overlapping PCR products that spanned the region between the unique restriction sites AatII andBglII were amplified, using two pairs of primers. The following primers were used in the combinations A + C and B + D: A (sense primer upstream of AatII), CGAGCATTGAAAACAATATC; B (antisense primer downstream ofBglII), GGAGATACAAGCGTCTTTCTTG; C (antisense primers complementary to wild-type PKA sites), S554/S555, TGGTGCGGAGAGGAAAATCT; S573, CTTGCTCTACTGTTGCGTCT;S610, TACAAATAGAGAGTCTCTTCTGC; S623, GCTGACATTGCTAGGACGCC; S686/S687/S688, GGTAAGAACTGGATCTCCTC; and D (sense primer upstream of wild-type PKA sites), CGGAAATCTGCCTCTGAGGA.

PCR conditions consisted of 2 ng of template, 1.25 μmdNTPs, 20 μm primers, 1.5 μmMgCl2, and 0.5 μl of Amplitaq polymerase (2.5 U/100 μl) in Amplitaq polymerase buffer (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA). The template was heat-denatured at 95°C, oligonucleotides were annealed at 50°C, and DNA was synthesized by Taq polymerase at 72°C. After 30 amplification cycles the products were gel-purified with a 1% agarose gel and Geneclean (Bio 101, Vista, CA). Then the two overlapping products for each construct were combined into one tube, and the region spanning AatII–BglII was amplified with the primers A and B described above. The final product was cut with AatII and BglII and ligated into the corresponding sites in the plasmid containing the full-length sodium channel.

Transcription of RNA and expression inXenopus oocytes

RNA transcripts were synthesized from NotI-linearized DNA templates by a T7 RNA polymerase Message Machine transcription kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). The yield of RNA was estimated by glyoxal gel analysis. Stage V oocytes were removed from adult female Xenopus laevis frogs, prepared as previously described (Goldin, 1991), and incubated in ND-96 media (96 mm NaCl, 2 mm KCl, 1.8 mm CaCl2, 1 mmMgCl2, and 5 mm HEPES, pH 7.5) supplemented with 0.1 mg/ml gentamicin, 0.55 mg/ml pyruvate, and 0.5 mm theophylline. Sodium channel RNA was injected at ∼100 pg/oocyte. After a 40 hr incubation at 20°C in ND-96, sodium currents were recorded with a two-electrode voltage clamp at room temperature, as previously described (Patton and Goldin, 1991). Sodium current amplitudes were between 1 and 5 μA. Acquisition and analysis were performed with pCLAMP 6.0.3 software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Capacitive transients and leak currents were corrected by P/4 subtraction. The bath recording solution consisted of ND-96, and PKA was induced by perfusing oocytes with a cocktail consisting of 25 μm forskolin, 10 μm chlorophenylthio-cAMP (cpt-cAMP), 10 μm dibutyryl-cAMP (db-cAMP), and 10 μm 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) for 10 min. These compounds all increase cytoplasmic cAMP levels and therefore can activate PKA. Forskolin activates adenyl cyclase, cpt-cAMP and db-cAMP are membrane-permeable stable analogs of cAMP, and IBMX is an inhibitor of phosphodiesterases that otherwise could convert cAMP to AMP. Forskolin was prepared at a stock concentration of 50 mm in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), cpt-cAMP and db-cAMP were prepared at stock concentrations of 10 mm in water, and IBMX was prepared at a stock concentration of 10 mm in EtOH. All of these reagents were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Stock solutions were stored at −20°C. The rate of perfusion with bath solution was adjusted carefully to 0.3 ml/min to minimize fluctuations in current amplitude resulting from changes in flow rate. In some cases there was drift in the peak current amplitude even after allowing for recovery from slow inactivation. In those cases the peak current measurements were adjusted by subtracting a linear relationship that was fit to data acquired during the first 10 min before PKA stimulation.

Isolation of sodium channel protein from oocytes

Pools of 40 oocytes were injected with 50 ng/oocyte of wild-type or mutant sodium channel RNA and 250 nCi of 35S-methionine (DuPont NEN, Boston, MA). Injection of 50 ng of RNA resulted in sodium current amplitudes of ∼50 μA. The wild-type and mutant sodium channels contained the FLAG epitope (DYKDDDDK) immediately after the start methionine codon. Insertion of FLAG did not alter the functional properties of the channel. 35S-methionine was injected to determine the total amount of sodium channel protein synthesized. Sodium channel protein was purified from the membrane fraction of oocytes by immunoprecipitation with M2 anti-FLAG antibody (VWR, Cerritos, CA), as previously described (Smith and Goldin, 1996). The proteins were analyzed on a 7.5% SDS polyacrylamide gel with a 3% stacking gel. The gel was fixed and washed two times with DMSO for 1 hr each time. To enhance the 35S signal by autoradiography, we soaked the gel in 2,5-diphenyloxazole (PPO) in DMSO for 1 hr and then washed it three times with water for 1 hr each. The gel was dried and analyzed by autoradiography (1 d exposure), and the 35S signal in bands corresponding to sodium channel protein was quantified by scanning densitometry. The gel autoradiograph in Figure 5 was scanned with a Hewlett Packard Scanjet IIcx/T with a transparency adapter, and band densities were quantified with SigmaScan software (Jandel, San Rafael, CA). Although all of the samples were treated identically and run on the same polyacrylamide gel, the lanes corresponding to the PKACOMP-D and ⊕Site2-D channels were positioned adjacent to the wild-type and PKACOMP-A lanes by Adobe Photoshop. The otherwise unmodified gel image was labeled and converted to a print.

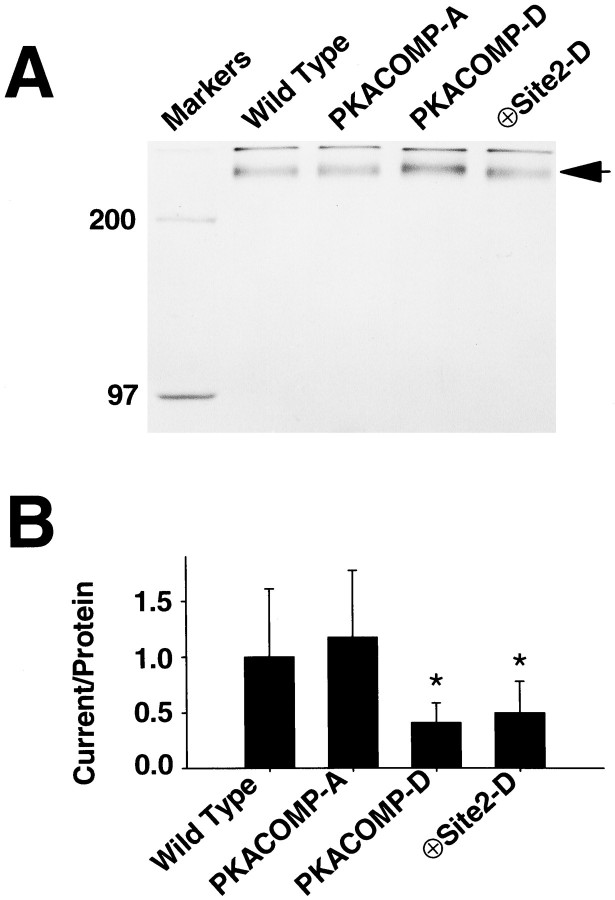

Fig. 5.

A negative charge at site 2 is sufficient to decrease sodium current amplitudes. A, Quantification of sodium channel protein. RNA encoding the sodium channel was injected into oocytes along with 35S-methionine to label the proteins metabolically. After 40 hr of incubation at 20°C, sodium channel protein was immunoprecipitated from the oocyte membrane fraction and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography, as described in Materials and Methods. The band representing sodium channel protein (indicated by an arrow; Mr ≈ 260 kDa) was scanned and quantified. Molecular weight markers of 200 and 97 kDa were run in the first lane of the gel. B, Sodium current normalized to the amount of membrane sodium channel protein. Peak current amplitudes were measured in representative oocytes by depolarizations to −20 mV from a holding potential of −100 mV (n = 15 oocytes). The sodium current magnitude was ∼50 μA in ND-96 bath solution. To maintain voltage control using a two-electrode voltage clamp with oocytes expressing such high levels of current, we reduced sodium in the bath by substitution with choline. Sodium current was normalized to the amount of protein isolated (A), and the ratios of current to protein were normalized to the ratio for the wild-type channel, which was set at 1.0. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. The normalized ratio of current to protein for the PKACOMP-A channel was not significantly different from that of the wild-type channel. The asteriskindicates that the ratios for the PKACOMP-D and ⊕Site2-D channels were significantly reduced, compared with the level of the wild-type channel, as determined by t test analysis (PKACOMP-D,p < 0.001; ⊕Site2-D, p < 0.05).

RESULTS

PKA sites in the I–II linker are required for current reduction

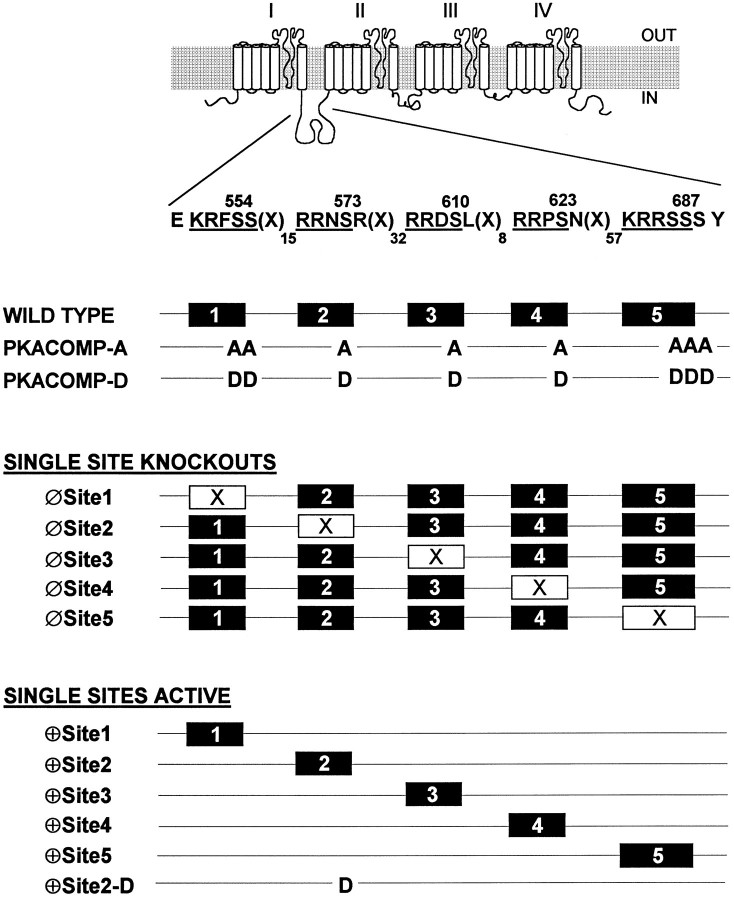

To examine the role of the five PKA consensus sites in the I–II linker of the sodium channel, we altered the sites by site-directed mutagenesis in three ways (Fig. 1). First, the five sites were eliminated collectively, replacing the serine residues with alanines to generate the PKA composite alanine mutant (PKACOMP-A) or with aspartates to generate the PKA composite aspartate mutant (PKACOMP-D), as previously described (Smith and Goldin, 1996). Because there are two and three serines present at PKA sites 1 and 5, respectively, all of the serines at those consensus sites were substituted. Second, to test if the individual sites were required for the reduction of current, we eliminated each individually (Fig. 1, Single Site Knock-outs). Finally, to determine if any of the individual PKA sites were sufficient to enable PKA-mediated current reduction, we constructed channels with single active sites (Fig. 1, Single Sites Active).

Fig. 1.

Diagram of PKA site mutant sodium channels. Diagram of the rat brain sodium channel, emphasizing the presence of the five consensus PKA phosphorylation sites (RRXS and KRXXS) in the cytoplasmic linker that connects domains I and II of the channel. Amino acid positions are indicated above the serine residues within the consensus sites, and the number of amino acids separating each site is indicated by the subscripts after the symbol X. For the PKACOMP-A mutant, all of the PKA sites were eliminated collectively by replacing all serine residues at the five sites with alanines. For the PKACOMP-D mutant, the serines were replaced with aspartates to mimic the negative charges resulting from phosphorylation. Single PKA sites were eliminated (Single Site Knock-outs) by replacing serines with alanines at each position. A second series of channels was constructed in which all of the sites except one were modified by serine to alanine substitutions (Single Sites Active). The ⊕Site2-D mutant has an aspartate at position 2 (S573D) in a channel in which all of the serines at the other I–II linker PKA sites have been replaced with alanines.

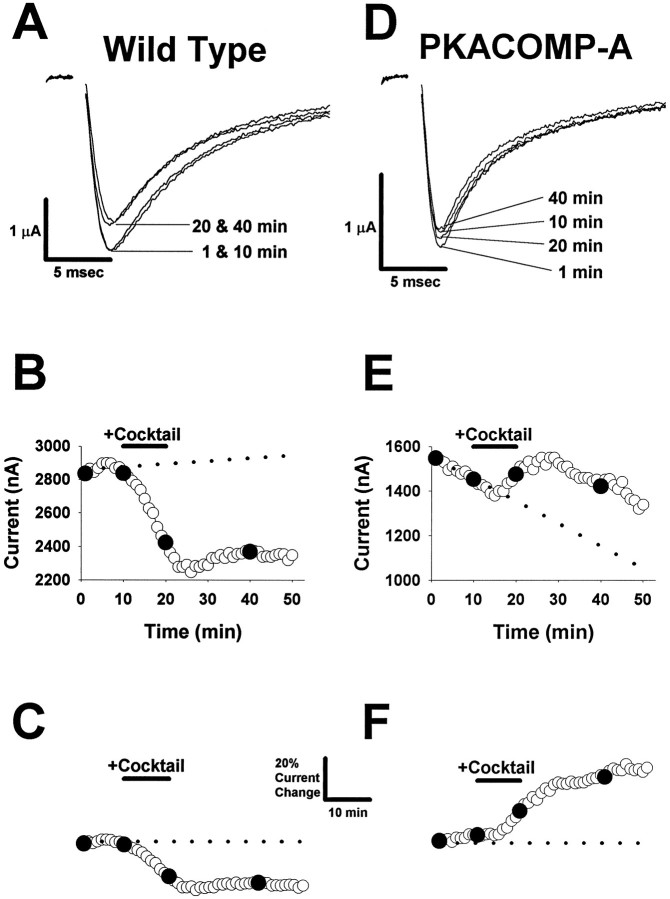

To measure the functional impact of PKA phosphorylation on the channel, we induced PKA in Xenopus oocytes while eliciting sodium currents by depolarizing pulses to −10 mV at 1 min intervals over a 50 min time course. Representative wild-type sodium current traces and the corresponding time course of peak current amplitudes are shown in Figure 2, A and B. The basal current level was determined during the first 10 min of recording. For the results shown in Figure 2, A andB, there was a slightly increasing trend, which is shown by the dashed line in Figure 2B. To compensate for the change in basal current, we fit data acquired during the first 10 min with a linear equation (indicated by the dotted line in Fig.2B), and we derived final peak current values by subtracting the linear fit from the measured peak current values (Fig.2C). Then the adjusted values were normalized to the baseline current during the first 10 min (Fig. 2C,dotted line).

Fig. 2.

PKA modulation of the sodium channel.A, Representative wild-type sodium current traces. Sodium currents were obtained by depolarizing pulses to −10 mV from a holding potential of −100 mV. Four traces are shown during depolarizations at 1, 10, 20, and40 min during a 50 min time course. PKA was induced in the oocyte as described in B during the 10–20 min time interval. B, Time course for wild-type peak current amplitude. Peak sodium current values are shown during a 50 min time course. The baseline current level was established during an initial 10 min interval (the dotted line represents a linear fit to the first 10 data points). PKA was induced during the 10 min time period indicated by the bar denoted Cocktail by perfusing with a PKA activation cocktail containing 25 μmforskolin, 10 μm cpt-cAMP, 10 μm db-cAMP, and 10 μm IBMX. Peak current values that correspond to the current traces in A (at 1, 10, 20, and 40 min) are indicated by the filled symbols. C, Adjusted and normalized time course for wild-type sodium channel peak current amplitude. The current values shown in B were adjusted by subtracting the linear relationship that was fit to the first 10 data points to compensate for the change in basal current. The adjusted values were normalized to the baseline current during the initial 10 min (dotted line). Calibration bars indicate a 20% relative change in current amplitude and a 10 min interval. D, Representative PKACOMP-A sodium current traces. Sodium currents were obtained by depolarizing pulses to −10 mV from a holding potential of −100 mV. Four traces are shown for time points obtained at1, 10, 20, and 40 min during a 50 min time course. PKA was induced in the oocyte as described in B during the 10–20 min time interval. E, Time course for PKACOMP-A peak current amplitude. Peak sodium current values are shown during a 50 min time course. The baseline current level was established during an initial 10 min interval (the dotted line represents a linear fit to the first 10 data points). PKA was induced during the 10 min time period indicated by the bardenoted Cocktail, as described in B. Peak current values that correspond to the current traces in D (at1, 10, 20, and 40 min) are indicated by the filled symbols. F, Adjusted and normalized time course for PKACOMP-A sodium channel peak current amplitude. The current values shown in E were adjusted by subtracting the linear relationship that was fit to the first 10 data points to compensate for the change in basal current. The adjusted values were normalized to the baseline current during the initial 10 min (dotted line). The calibration bars are shown inC and indicate a 20% relative change in current amplitude and a 10 min interval.

A PKA activation cocktail containing a mixture of 25 μmforskolin, 10 μm cpt-cAMP, 10 μm db-cAMP, and 10 μm IBMX was perfused for a 10 min interval, as indicated by the bar denoted Cocktail (Fig. 2B,C). For the wild-type channel, activation of PKA reduced sodium current amplitude at the 20 min time point by 17% relative to baseline (Fig. 2A–C), but there was no effect on the kinetics of inactivation. In addition, there were no effects on either the voltage dependence of conductance or inactivation (data not shown). These results are in agreement with previous reports showing that PKA phosphorylation attenuates sodium currents without affecting either the kinetics or voltage-dependent properties of the channels (Gershon et al., 1992; Li et al., 1992; Smith and Goldin, 1996).

When sodium currents were measured from the PKACOMP-A channel, a consistent and marked decrease in basal current amplitude was observed (Fig. 2D, E). This decreasing trend was linear over a 50 min interval in oocytes in which PKA was not induced (data not shown). For the representative data shown in Figure2E, the current amplitude decreased from ∼1550 to 1450 nA during the first 10 min before PKA activation. The magnitude of this baseline change was the largest that we observed with any of the mutants. To compensate for the changing baseline, we fit data acquired during the first 10 min with a linear equation (Fig.2E, dotted line), which was subtracted from the measured peak current values, as described for the wild-type channel. The adjusted values were normalized finally to the level of current during the first 10 min of recording (Fig.2F, dotted line).

In contrast to the wild-type channel, the PKACOMP-A sodium channel did not show a reduction in current in response to PKA induction, confirming that the five PKA sites are essential for PKA-mediated current reduction (Smith and Goldin, 1996). Instead, elimination of the five PKA sites resulted in a channel that showed an enhancement of current in response to PKA induction. The increase in current size for the representative example shown in Figure 2F was 15% at the 20 min time point, but the current continued increasing until reaching a final level of 32% above baseline at the 40 min time point (30 min after PKA induction). The mechanism that causes this enhancement of current is not understood, but it is consistent with previous studies on the rat brain (Smith and Goldin, 1992, 1996) and cardiac (Frohnwieser et al., 1997) sodium channels. Apparently, there is a secondary PKA-triggered event that increases the amplitude of whole-cell sodium current in oocytes. Although this enhancement of current is striking, we do not address this effect in this paper. Instead, we have focused on whether the presence or absence of the individual I–II linker sites enables reduction of sodium current amplitude by PKA.

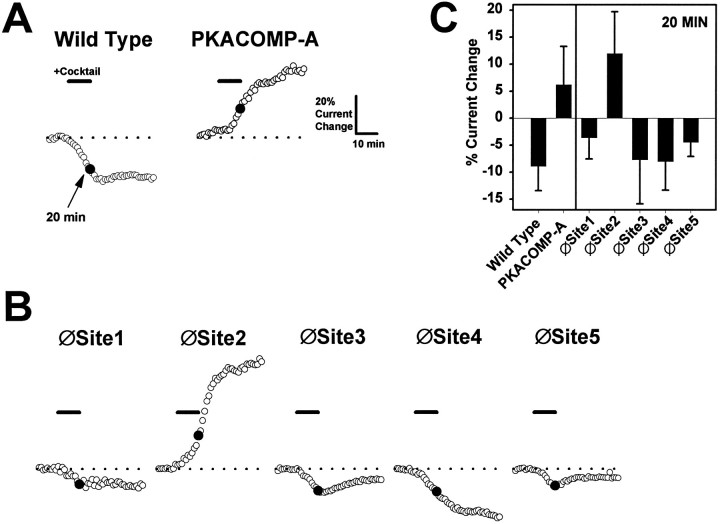

Site 2 is necessary for current reduction by PKA

To test the importance of each of the five PKA sites for mediating sodium current reduction, we individually eliminated the sites by replacing serines with alanines (Fig. 1, Single Site Knock-outs). The responses of these channels to PKA induction are summarized in Figure 3, B andC. For the purpose of comparison, representative responses to PKA induction are shown again for the wild-type and PKACOMP-A channels (Fig. 3A). The average reduction in current size for the wild-type channel in multiple oocytes was 9% at the 20 min time point, as indicated in Figure 3C. The average increase in current amplitude for the PKACOMP-A channel measured in multiple oocytes was 6% at the 20 min time point. Elimination of PKA sites 1, 3, 4, or 5 did not significantly alter the response of the channel to PKA induction when compared with the wild-type channel. Each of these mutants demonstrated reductions in current amplitude that ranged between 4 and 8% at the 20 min time point. In marked contrast, removal of site 2 (∅Site2) completely eliminated the PKA-mediated reduction of current amplitude. Instead, this channel showed a pronounced 12% enhancement of current, similar to the response of the PKACOMP-A channel in which all of the PKA sites are absent. The data are summarized in Figure 3C and demonstrate that only the removal of site 2 abolishes the reduction of current by PKA. Therefore, site 2 is necessary for PKA-mediated current attenuation.

Fig. 3.

Site 2 is necessary for current reduction by PKA.A, Representative time courses for wild-type and PKACOMP-A channels. Adjusted and normalized peak current amplitudes are shown for representative oocytes injected with RNA encoding the wild-type and PKACOMP-A mutant channels. Currents were elicited by step depolarizations from a holding potential of −100 to −10 mV, with a sampling interval of 1 min. Peak current amplitudes were adjusted and normalized as described in Figure 2C, F. The basal level of current, indicated by the dashed lines, was established during an initial 10 min interval. PKA was induced by perfusion with a cocktail (25 μm forskolin, 10 μm cpt-cAMP, 10 μm db-cAMP, and 10 μm IBMX) for 10 min, as indicated by the solid bar denoted Cocktail. The 20 min time point (indicated by solid circles) was chosen to emphasize the reduction in current for the wild-type channel and the enhancement of current for the PKACOMP-A channel after PKA induction. Scale bars indicate a 10 min interval and a 20% change in current amplitude. B, Representative time courses for single site knock-out mutants. Adjusted and normalized peak current amplitudes are shown for sodium channels lacking single PKA sites. PKA was induced by a 10 min perfusion of cocktail, as indicated by the solid bars. Recording conditions and time and amplitude scales are the same as inA. C, Average percentage of changes in current amplitudes. The percentages of current change at the 20 min time points are plotted for each of the channels represented in A andB. The values reflect the average change in current amplitude with corresponding SD values for each of the different sodium channels 10 min after PKA induction. Sample sizes were wild-type, 9; PKACOMP-A, 8; and 5 for each of the single site knock-out mutants.

Site 2 is sufficient for current reduction by PKA

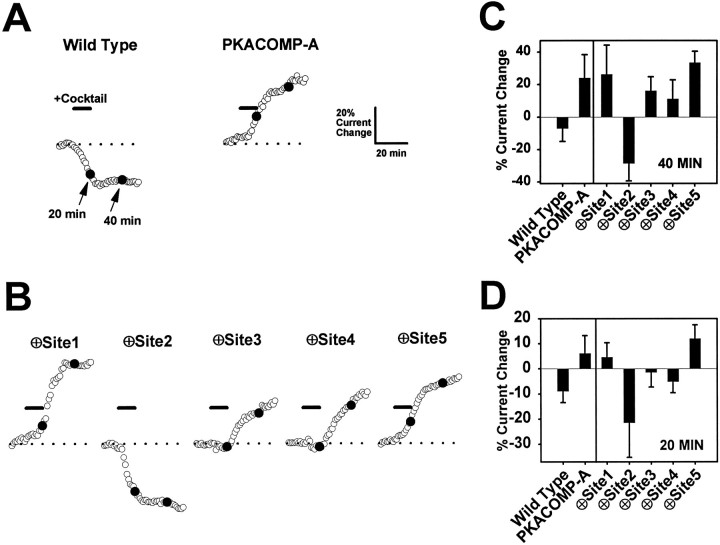

To determine if single PKA sites when present alone are sufficient to mediate a reduction in current amplitude, we tested channels in which each of the five sites was individually present (Fig. 1,Single Sites Active). For the purpose of comparison, representative responses to PKA induction of the wild-type and PKACOMP-A channels are shown again in Figure4A. When the channels with single sites active were tested, it was observed that a single PKA site at position 1, 3, 4, or 5 did not enable current reduction at the 40 min time point (Fig. 4B, C). In fact, these channels behaved in a manner similar to the PKACOMP-A mutant, showing increases of 11–33% in current size (Fig. 4C). In striking contrast, when only the PKA site at position 2 was active (⊕Site2), there was a pronounced 28% reduction in current amplitude, similar to the type of response observed with the wild-type channel (Fig. 4B, C). Therefore, the results for the ∅Site2 and ⊕Site2 channels are in complete accordance and, taken together, show that PKA phosphorylation of serine 573 is both necessary and sufficient for the attenuation of sodium current amplitude.

Fig. 4.

Site 2 is sufficient for current reduction by PKA.A, Representative time courses for the wild-type and PKACOMP-A channels. Adjusted and normalized peak current amplitudes are shown for representative oocytes injected with RNA encoding the wild-type and PKACOMP-A mutant channels. Currents were elicited by step depolarizations from a holding potential of −100 to −10 mV at a sampling interval of 1 min. Peak current amplitudes were adjusted and normalized as described in Figure 2C, F. The basal level of current (indicated by the dashed lines) was established during an initial 10 min interval. PKA was induced by perfusion with a cocktail (25 μm forskolin, 10 μm cpt-cAMP, 10 μm db-cAMP, and 10 μm IBMX) for 10 min, as indicated by the solid bar denoted Cocktail. The 20 and 40 min time points (indicated by solid circles) were chosen to emphasize the PKA-mediated reduction in current at both times for the wild-type channel, in contrast to the enhancement of current for the PKACOMP-A channel. Scale bars indicate a 10 min interval and a 20% change in current amplitude. B, Representative time courses for channels with single active PKA sites. Adjusted and normalized peak current amplitudes are shown for sodium channels that have single PKA sites present. PKA was induced by a 10 min perfusion of cocktail, as indicated by the solid bars. Recording conditions and time and amplitude scales are the same as in A. The 20 and 40 min time points (solid circles) are highlighted to emphasize the initial reduction in current at 20 min for the ⊕Site3 and ⊕Site4 channels and the enhancement of current at 40 min for these channels after PKA induction. C, Average percentage of changes in current amplitudes at 40 min. The percentage of current change at the 40 min time points is shown for each of the channels represented inA and B. These values reflect the average change in current amplitude with corresponding SD values for each of the channels 30 min after PKA induction. Sample sizes were wild-type, 9; PKACOMP-A, 8; and 8, 6, 7, 8, and 5 for channels with single sites active at positions 1–5, in that order. D, Average percentage of changes in current amplitudes at 20 min. The percentage of current change at the 20 min time points is shown for each of the channels represented in A and B. These values reflect the average change in current amplitude with corresponding SD values for each of the channels 10 min after PKA induction. The sample sizes were the same as forC.

PKA can act through sites 3 and 4 to produce a minor amount of current reduction

Although the PKA sites at positions 3 and 4 (⊕Site3 and ⊕Site4) did not mediate a reduction in current at the 40 min time point, there was initially a minor reduction in current at the 20 min time point for both of these channels (Fig. 4B,D). The magnitude of the reduction was significantly less than that for the wild-type and ⊕Site2 channels. The ⊕Site2 channel showed a dramatic reduction in current of 21%, whereas the ⊕Site3 and ⊕Site4 channels demonstrated average reductions of only 1 and 5%, respectively. The reductions for the ⊕Site3 and ⊕Site4 channels were significantly (p < 0.05) different from the 6% increase observed for the channel lacking all five PKA sites (PKACOMP-A). The decreases for the ⊕Site3 and ⊕Site4 channels were followed by increases in current amplitude by the 40 min time point (Fig. 4C). At 40 min, the ⊕Site2 channel continued to show an average reduction in current of 28%, whereas the ⊕Site3 and ⊕Site4 channels demonstrated significant increases of 16 and 11%, respectively. Therefore, sites 3 and 4 mediated small reductions in sodium current amplitude, but the effects were considerably smaller than that observed for site 2.

Negative charge at site 2 reduces sodium current

We previously reported that addition of negative charges at all five of the PKA sites resulted in a channel that expressed a constitutively reduced level of current (Smith and Goldin, 1996). This channel was called the PKA site composite aspartate mutant (PKACOMP-D) and is depicted in Figure 1. Having established that phosphorylation at site 2 alone is sufficient to reduce the level of sodium current, we wanted to determine if a single negative charge at position 2 could reduce the basal level of current. We therefore replaced the serine residue at site 2 with an aspartate (Fig. 1, ⊕Site2-D). The basal level of current was compared for the wild-type, PKACOMP-A, PKACOMP-D, and ⊕Site2-D channels (Fig.5). Because it was possible that these different sodium channels were expressed at different levels, we normalized the current amplitude that was measured in representative oocytes expressing each mutant to the corresponding amount of membrane channel protein that subsequently was isolated from the same oocytes. To quantify sodium channel protein, we metabolically labeled the oocytes with 35S-methionine, followed by immunoprecipitation of the sodium channels from the oocyte membrane fraction. Then the proteins were analyzed by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography (Fig. 5A). Finally, the ratios of current to protein were all normalized to the ratio for the wild-type channel, which was set at 1.0 (Fig. 5B). The basal current amplitudes that were expressed for the wild-type and PKACOMP-A channels were not significantly different from each other. On the other hand, the basal current amplitudes for the PKACOMP-D and ⊕Site2-D channels were reduced significantly to 43 ± 19 and 53 ± 29% relative to the level of the wild-type channel, respectively. Therefore, a single negative charge at site 2 (serine-573) significantly reduced basal sodium current amplitude.

DISCUSSION

Site 2 is necessary and sufficient for current reduction by PKA

To gather evidence about the molecular mechanism for sodium current attenuation by PKA, we have measured the relative contributions of the five consensus PKA sites located in the I–II linker of the rat brain sodium channel. Our key finding is that phosphorylation at site 2 is of primary importance. When site 2 was eliminated (∅Site2), the reduction of current amplitude by PKA induction was abolished completely, demonstrating that this site is required. Furthermore, when site 2 was the only PKA site present (⊕Site2), current amplitude was reduced by an average of 28% 30 min after PKA induction (the 40 min time point), demonstrating that this site has the most prominent role in PKA attenuation. Finally, we demonstrated that the attenuation of current could be accounted for by the introduction of a negative charge at PKA site 2.

Minor reduction of current by sites 3 and 4

In addition to the primary effect of PKA at site 2, PKA induction brought about minor reductions in current when sites 3 or 4 were present. In those two cases sodium current was reduced by only 1–5% 10 min after PKA induction (the 20 min time point), and these channels subsequently demonstrated an enhancement of current amplitude. Current reduction and enhancement are mediated by two separate mechanisms, because these effects can be separated by eliminating the I–II linker PKA sites (compare the wild-type and PKACOMP-A channels). We conclude that the enhancement of sodium current normally competes with the reduction. These two effects can be distinguished temporally for the ⊕Site3 and ⊕Site4 channels for which the reduction of current is most pronounced at the 20 min time point, whereas the enhancement of current predominates later. The delay in current enhancement suggests that the increase in current amplitude may occur by an indirect pathway, as opposed to the direct phosphorylation of the sodium channel protein that causes current attenuation.

The sites where modulation occurs are optimal target motifs for PKA phosphorylation

By comparing peptide sequences from known PKA substrates, it has been determined that the most common target motif for PKA is RRXS, with X representing any amino acid (Kemp and Pearson, 1990). The sodium channel PKA consensus sites at positions 2, 3, and 4 are RRNS, RRDS, and RRPS, respectively, which makes them all optimal targets. Therefore, it is not surprising that PKA can modulate the channel by phosphorylation at these sites. However, the KRRSSS sequence at position 5 also contains the same motif, and yet no functional impact because of phosphorylation at this site was observed. Perhaps phosphorylation does occur at site 5 in oocytes, but the functional effects are either nonexistent or undetectable by this type of analysis. Finally, the PKA site at the first position is not optimal (KRFSS), although the consensus KRXXS has been observed to be phosphorylated by PKA (Kemp and Pearson, 1990). We observed no functional impact when site 1 either was eliminated or was present by itself, suggesting that this site does not play a significant role in sodium channel modulation by PKA.

There is biochemical evidence showing selective phosphorylation of the I–II linker PKA sites both in vivo and in vitro (Murphy et al., 1993). After metabolic labeling, site 5 was determined to be the most highly phosphorylated in vivo, followed by sites 2, 4, and 3, in that order. In vitro, site 4 was the most extensively phosphorylated, whereas sites 2, 3, and 5 were phosphorylated to lesser extents. Phosphorylation was not detected at site 1, consistent with our data that there is no functional consequence of having site 1 present. Our data are therefore in agreement with the biochemical data with regard to sites 1, 2, 3, and 4, with the conclusion that PKA phosphorylation occurs at sites 2, 3, and 4, and the addition of phosphate residues at any of these sites reduces sodium current. However, there is not a good correlation between the extent of phosphorylation at each site and the relative functional impact. Site 2 is phosphorylated to a lesser extent than site 5, yet site 2 is the primary position at which attenuation of current occurs. Because the amount of phosphorylation at individual sites does not correlate with the functional impact, this indicates that some sites are more functionally sensitive than others.

The different sensitivities of the PKA sites provides a mechanism by which sodium channel activity, and hence neuronal excitability, could be modulated. Site 5 is phosphorylated preferentially, so this site is likely to be phosphorylated first under conditions of low PKA activity, but with minimal functional impact. Induction of PKA activity would result in phosphorylation at some or all of PKA sites 2, 3, and 4. Phosphorylation at sites 3 or 4 would cause minor attenuation of sodium current, whereas phosphorylation at site 2 would result in a large reduction in current amplitude. Therefore, nerve cells could attenuate sodium current incrementally by increasing the level of PKA activity. Additional regulation could be provided by differential sensitivity of each of the sites to dephosphorylation by protein phosphatases. Brain calcineurin, phosphatase 1, and phosphatase 2A are all able to dephosphorylate the sodium channel differentially at sites 2–5 (Murphy et al., 1993; Chen et al., 1995). Therefore, the combined actions of PKA and phosphatases could allow the sodium current to be regulated precisely.

Molecular models for modulation by PKA phosphorylation

The molecular mechanism by which phosphorylation in the I–II linker decreases sodium current amplitude is unknown. Given the different functional impact of phosphorylation at positions 2, 3, 4, and 5, it is evident that there must be some positional specificity. One possibility is that the I–II linker has a specific conformation that is modified by phosphorylation. The linker might interact either with other regions of the sodium channel or with other protein molecules that are in close proximity, and phosphorylation could dictate whether or not those interactions take place. The rat brain sodium channel is known to interact with other molecules, such as the accessory subunits β1 and β2. However, those interactions are not necessary for functional modulation by PKA either in Xenopus oocytes (Gershon et al., 1992; Smith and Goldin, 1996) or CHO cells (Li et al., 1992, 1993). The rat brain sodium channel also is known to interact with the cytoskeletal proteins ankyrin and spectrin (Srinivasan et al., 1988), and it is possible that phosphorylation might affect those interactions, with functional consequences for the channel.

The onset and development of PKA modulation is quite rapid, occurring within 5 min after PKA induction. In addition, the reduction in current amplitude is reversible, with a return to baseline levels within 1 hr after PKA stimulation (Smith and Goldin, 1996). The rapid onset of modulation by PKA is consistent with models that are not diffusion-limited. The reversibility of current attenuation within a 1 hr time period suggests that it does not occur by a reduction in the number of sodium channels in the membrane, because the time course is too rapid to be explained by the addition of new channels to the membrane from intracellular stores. The reduction is not likely to involve fast inactivation, because induction of PKA has no impact on the kinetics of fast inactivation, and the reduction also occurs in a channel in which fast inactivation has been removed by the IFM to QQQ mutation (West et al., 1992) in the III–IV linker (R. Smith and A. Goldin, unpublished observations). It is more likely that phosphorylation decreases either the open probability of the channel, as was shown to be the case in excised patches from transfected CHO cells (Li et al., 1992), or the single-channel conductance. The effects of PKA induction on these properties of the sodium channel expressed inXenopus oocytes will be determined by single-channel analysis. In either case, the presence of a negative charge at phosphorylation site 2 in the I–II linker is both necessary and sufficient for sodium channel modulation by PKA.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grant NS26729 to A.L.G. from National Institutes of Health. A.L.G. is an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association. We thank Drs. Kris Kontis, Michael Pugsley, Linda Hall, Ted Shih, and Marianne Smith for helpful discussions during the course of this work. We acknowledge Esther Yu and Mimi Reyes for excellent technical assistance.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Alan L. Goldin at the above address.

REFERENCES

- 1.Auld VJ, Goldin AL, Krafte DS, Catterall WA, Lester HA, Davidson N, Dunn RJ. A neutral amino acid change in segment IIS4 dramatically alters the gating properties of the voltage-dependent sodium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:323–327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen T-C, Law B, Kondratyuk T, Rossie S. Identification of soluble protein phosphatases that dephosphorylate voltage-sensitive sodium channels in rat brain. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7750–7756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costa MR, Catterall WA. Cyclic AMP-dependent phosphorylation of the alpha subunit of the sodium channel in synaptic nerve ending particles. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:8210–8218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costa MR, Casnellie JE, Catterall WA. Selective phosphorylation of the alpha subunit of the sodium channel by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:7918–7921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frohnwieser B, Chen L-Q, Schreibmayer W, Kallen RG. Modulation of the human cardiac sodium channel α-subunit by cAMP-dependent protein kinase and the responsible sequence domain. J Physiol (Lond) 1997;498:309–318. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gershon E, Weigl L, Lotan I, Schreibmayer W, Dascal N. Protein kinase A reduces voltage-dependent Na+ current in Xenopus oocytes. J Neurosci. 1992;12:3743–3752. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-10-03743.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldin AL. Expression of ion channels by injection of mRNA into Xenopus oocytes. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;36:487–509. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hopp TP, Prickett KS, Price VL, Libby RT, March CJ, Cerretti DP, Urdal DL, Conlon PJ. A short polypeptide marker sequence useful for recombinant protein identification and purification. Biotechnology. 1988;6:1204–1210. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kemp BE, Pearson RB. Protein kinase recognition sequence motifs. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990;15:342–346. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90073-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li M, West JW, Lai Y, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Functional modulation of brain sodium channels by cAMP-dependent phosphorylation. Neuron. 1992;8:1151–1159. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90135-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li M, West JW, Numann R, Murphy BJ, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Convergent regulation of sodium channels by protein kinase C and cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Science. 1993;261:1439–1442. doi: 10.1126/science.8396273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy BJ, Rossie S, DeJongh KS, Catterall WA. Identification of the sites of selective phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of the rat brain Na+ channel α subunit by cAMP-dependent protein kinase and phosphoprotein phosphatases. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:27355–27362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patton DE, Goldin AL. A voltage-dependent gating transition induces use-dependent block by tetrodotoxin of rat IIA sodium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Neuron. 1991;7:637–647. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90376-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossie S, Catterall WA. Cyclic AMP-dependent phosphorylation of voltage-sensitive sodium channels in primary cultures of rat brain neurons. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:12735–12744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rossie S, Catterall WA. Phosphorylation of the alpha subunit of rat brain sodium channels by cAMP-dependent protein kinase at a new site containing ser686 and ser687. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:14220–14224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossie S, Gordon D, Catterall WA. Identification of an intracellular domain of the sodium channel having multiple cAMP-dependent phosphorylation sites. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:17530–17535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schiffmann SN, Lledo P-M, Vincent J-V. Dopamine D1 receptor modulates the voltage-gated sodium current in rat striatal neurones through a protein kinase A. J Physiol (Lond) 1995;483:95–107. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith RD, Goldin AL. Protein kinase A phosphorylation enhances sodium channel currents in Xenopus oocytes. Am J Physiol. 1992;236:C660–C666. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.263.3.C660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith RD, Goldin AL. Phosphorylation of brain sodium channels in the I–II linker modulates channel function in Xenopus oocytes. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1965–1974. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-06-01965.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srinivasan Y, Elmer L, Davis J, Bennett V, Angelides K. Ankyrin and spectrin associate with voltage-dependent sodium channels in brain. Nature. 1988;333:177–180. doi: 10.1038/333177a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.West JW, Patton DE, Scheuer T, Wang Y, Goldin AL, Catterall WA. A cluster of hydrophobic amino acid residues required for fast Na+ channel inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10910–10914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]