Introduction

In 2013, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) revised its mission, “We improve health care and population health by assessing and advancing the quality of resident physicians' education through accreditation,” adding “population health” explicitly to its charge. This change reflects the importance of population health in the preparation of resident physicians to meet the Triple Aim.1 The ACGME fulfills its mission in graduate medical education (GME) through efforts that support ongoing assessment and evaluation of individual learners, programs, and sponsoring institutions. The Common Program Requirements (CPRs) are the accreditation standards that outline the structure, processes, and outcomes that define common characteristics of specialty and subspecialty educational programs for physicians in the United States. The CPRs provide the basis for the ACGME's accreditation decisions, evaluation of the competencies, and requirements for training applicable to all specialties.

Over the last 4 years the CPRs have undergone a major revision. This effort was accomplished in 2 phases following the review of requested comments and recommendations from more than 120 medical organizations, societies, certifying entities, residents, and others. The Phase 1 Task Force was charged with conducting an in-depth review of Section VI of the CPRs that addresses the characteristics of the resident work and learning environment.2 They were informed by emerging concern over resident and faculty well-being. In 2017, the Phase 1 Task Force announced a major revision to Section VI of the CPRs, incorporating new requirements centered around resident work hours, physician well-being, and support. The Phase 2 Task Force initiated its efforts to revise the remaining sections of the CPRs (Sections I–V) with an evidence-based approach, outlining the philosophy and intent of the updated standards. The new requirements are effective July 1, 2019, with a few exceptions and will be fully implemented as of July 1, 2020. It is in Sections I–V that the interface between the program and the community it serves and the health of the public emerges in philosophy and standards.

The revision of the CPRs follows a report published by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), titled Graduate Medical Education That Meets the Nation's Health Needs. While the IOM committee's charge was primarily focused on GME governance and financing, the entire report centered around GME that “supports the nation's health and health care goals, as articulated in the ‘triple aim.'”3 This basic tenet is reiterated in the first goal of the committee to “encourage production of a physician workforce better prepared to work in, to help lead, and to continually improve an evolving health care delivery system that can provide better individual care, better population health, and lower cost.”3 The factors that lead to improved population health outcomes encompass a broad range of interventions from safety and quality in the acute care setting to improved behavioral and social conditions, with the latter having the greatest impact on health outcomes overall.4 Despite this awareness, social spending as a ratio to health care spending in the United States lags behind that of other industrialized countries, a factor likely contributing to poor health outcomes in the United States compared to other nations.5 These poor outcomes are disproportionately concentrated in regions and populations across the country. Using life expectancy as a measure of health status, for example, life expectancy by county in the United States in 2014 ranged from approximately 66 years to 87 years, a more than 20-year difference.6 The importance of population health in educating the next generation of physicians is critical to addressing these disparities. Physicians need to understand the impact of factors in both the medical delivery system and the social environment that contribute to health outcomes.

As the ACGME strives to fulfill its mission, of particular interest is whether or not the updated CPRs sufficiently reflect “population health” to ensure that GME prepares residents and fellows to meet the needs of the public. In this review of the CPRs, we explore the elements of the standards that introduce engagement in population health and community health by programs and sponsoring institutions.

Methods

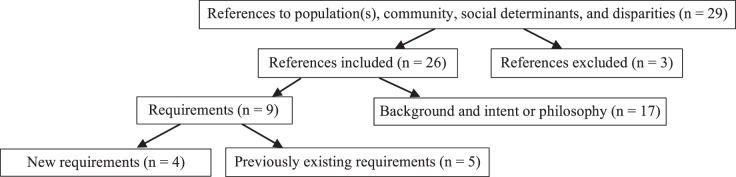

Population health is defined as “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group.”7 Groups can be defined in any number of ways and include communities, regions, countries, and demographic characteristics. To capture both “population health” and factors that contribute to health outcomes, a word search of the new CPRs was conducted to identify references to the following terms: population(s), community, social determinants, and disparities. These words were chosen to capture any reference to population health, community health needs, and the understanding of social determinants of health and disparities in care. References identified in the search that did not pertain to population health were excluded from the analysis. The remaining references were separated into 2 categories: requirements and philosophy, which include references to the topic in the background and intent. This is an important distinction as philosophical statements may describe the overall purpose, goals, and framework for the standards; however, programs may only be cited for specific requirements. Finally, the same word search was conducted on the current CPRs to note any requirements that are part of the existing set of standards, unchanged in the newly revised version.

Results

The Figure shows the results of the word search and the number of references captured in each step. There were 29 total references to population(s), community, social determinants, and disparities, of which 3 were excluded from our analysis (all 3 were references to “community”: the GME community, the academic community, or community sites). Approximately two-thirds of the remaining references were in the background and intent and philosophic statements (n = 17) and one-third were contained in specific requirements (n = 9). The Table shows the full list of requirements included in the analysis, noting the ones not new to this revision. The new references related to population health (n = 4) are embedded in the requirements for program director responsibilities, the overall design of the educational program, resident attainment of competencies in systems-based practice, and faculty scholarly activity (as one of many domains of study). The emphasis of the new requirements is on addressing community health needs and understanding social determinants of health, areas that may have been incorporated in specialty-specific standards but not previously included in the CPRs, applicable to all specialties. The previously existing references (n = 5) focus on competencies in professionalism and systems-based practice: reducing disparities, quality improvement in population-based care, and caring for diverse populations within the clinical learning environment. The references to population health in the Background and Intent and Philosophy statements focus on the program's responsibility to the “community it serves,” the community's health needs, and improving health of both the individual and the population. Either in Background and Intent and Philosophy or in the requirements, 4 out of the 6 sections of the new CPRs contain population health references: Oversight, Personnel, Educational Program, and The Learning and Working Environment.

Figure.

Summary of Population Health Text References in ACGME's New Common Program Requirements

Table.

New Common Program Requirements Containing References to Population(s), Community, Social Determinants, and Disparities

| Description | Requirement | Text |

| Personnel, program director, program director responsibilities | II.A.4.a).(2) | The program director must design and conduct the program in a fashion consistent with the needs of the community, the mission(s) of the sponsoring institution, and the mission(s) of the program; |

| Educational program | IV.A.1. | The curriculum must contain the following educational components: a set of program aims consistent with the sponsoring institution's mission, the needs of the community it serves, and the desired distinctive capabilities of its graduates; (Core) |

| Educational program, ACGME competencies, professionalisma | IV.B.1.a).(1).(e) | Residents must demonstrate competence in respect and responsiveness to diverse patient populations, including but not limited to diversity in gender, age, culture, race, religion, disabilities, national origin, socioeconomic status, and sexual orientation; (Core) |

| Educational program, ACGME competencies, systems-based practice | IV.B.1.f) | Residents must demonstrate an awareness of and responsiveness to the larger context and system of health care, including the social determinants of health, as well as the ability to call effectively on other resources to provide optimal health care. (Core) |

| Educational program, ACGME competencies, systems-based practicea | IV.B.1.f).(1).(f) | Residents must demonstrate competence in incorporating considerations of value, cost awareness, delivery and payment, and risk-benefit analysis in patient and/or population-based care as appropriate; and, (Core) |

| Educational program, scholarship, faculty scholarly activity | IV.D.2.a) | Among their scholarly activity, programs must demonstrate accomplishments in at least 3 of the following domains: (Core)

|

| The learning and working environment, patient safety, quality improvement, supervision, and accountability; quality improvementa | VI.A.1.b).(1).(a) | Residents must receive training and experience in quality improvement processes, including an understanding of health care disparities. (Core) |

| The learning and working environment, patient safety, quality improvement, supervision, and accountability; quality metricsa | VI.A.1.b).(2).(a) | Residents and faculty members must receive data on quality metrics and benchmarks related to their patient populations. (Core) |

| The learning and working environment, patient safety, quality improvement, supervision, and accountability; engagement in quality improvement activitiesa | VI.A.1.b).(3) | Residents must have the opportunity to participate in interprofessional quality improvement activities. (Core) This should include activities aimed at reducing health care disparities. (Detail) |

Previously existing requirements.

Discussion

The introduction to the CPRs defines the GME experience as the transformational phase of medical education between medical school and clinical practice.8 The development of physicians in GME is focused on “excellence in delivery of safe, equitable, affordable, quality care; and the health of the populations they serve.”8 In other words, both high-quality patient care and population health are critical goals of physician practice—a concept not new to medicine but a concept that has faced challenges in the way medical and public health education, the health care system, and the health needs of the public have evolved over time.9 In addition to the characteristics of an individual physician, the contents of the Background and Intent and the new requirements of the CPRs introduce the need for physicians to be trained in population health during their GME experience. Requirement II.A.4.a). states that “the program director must design and conduct the program in a fashion consistent with the needs of the community, the mission(s) of the Sponsoring Institution, and the mission(s) of the program.”8 The Background and Intent expands on this concept: “The mission of institutions participating in graduate medical education is to improve the health of the public. Each community has health needs that vary based upon location and demographics. Programs must understand the social determinants of health of the populations they serve and incorporate them in the design and implementation of the program curriculum, with the ultimate goal of addressing these needs and health disparities.”8 These statements reinforce the population health efforts of a GME system designed to address community needs, social determinants of health, and disparities in care. There is an increased emphasis on programs and sponsoring institutions designed to serve the needs of the community, incorporating social determinants of health in the educational program, resonating with growing trends and identified needs across medical education.3,10,11

These changes have important implications for the future health care workforce of our nation. Researchers have demonstrated that differences in complication rates and costs translate from the educational setting to practice and persist decades into the future.12,13 It would be logical to assume that participation and exposure to population health practices (or lack thereof) would also persist from GME to future practice. Requirements for GME that specifically point to community needs will help to ensure a future workforce with the appropriate skills to fulfill the Triple Aim as community health needs evolve over time. Training physicians to think broadly about their potential impact and to understand social factors that influence outcomes is an important step in finding ways to reduce inequities in health outcomes across the country.

Finally, there are several philosophies that contribute to the concept of physician professionalism and have formed the basis of the social contract between physicians and the public.14 Physicians are called to engage in more than a monetary transaction for health care services. They are called to be healers and moral agents in the communities they serve. By employing population health methodologies and partnering with community health experts and to engage with patients where they live, work, eat, and play, physicians can work with their communities to create targeted programs that address health care needs. Identifying ways physicians can effectively contribute to overall population health outcomes serves the public's needs and resonates with the profession's deepest values and healing purpose in fulfillment of the social contract.15

Conclusion

Through its proposed accreditation requirements, the ACGME is taking a step toward a greater emphasis on population health in GME. To fulfill its mission and to meet the needs of the public, the ACGME can act as a convener of the GME community's collective efforts, providing encouragement for population health initiatives, including broader awareness of the impact of social factors on health outcomes. Our communities deserve our very best effort to continually understand disparities and to work together to improve population health.

References

- 1.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Milwood) 2008;27(3):759–769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burchiel KJ, Zetterman RK, Ludmerer KM, Philibert I, Brigham TP, Malloy K, et al. The 2017 ACGME Common Work Hour Standards: promoting physician learning and professional development in a safe, humane environment. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(6):692–696. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-17-00317.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Committee on the Governance and Financing of Graduate Medical Education. Board on Health Care Services. Institute of Medicine. Eden J, Berwick D, Wilensky G, Medical G, Care H. Graduate Medical Education That Meets the Nation's Health Needs. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(4):590–595. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, Jha AK. Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA. 2018;319(10):1024–1039. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dwyer-Lindgren L, Bertozzi-Villa A, Stubbs RW, Morozoff C, Mackenbach JP, van Lenthe FJ, et al. Inequalities in life expectancy among US counties, 1980 to 2014: temporal trends and key drivers. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):1003–1011. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kindig D, Stoddart G. What is population health? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(3):380–383. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.3.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements (Residency) 2018:1–60. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency2019-TCC.pdf Accessed April 18, 2019.

- 9.Maeshiro R, Johnson I, Koo D, Parboosingh J, Carney JK, Gesundheit N, et al. Medical education for a healthier population: reflections on the Flexner report from a public health perspective. Acad Med. 2010;85(2):211–219. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c885d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siegel J, Coleman DL, James T. Integrating social determinants of health into graduate medical education: a call for action. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):159–162. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duval JF, Opas LM, Nasca TJ, Johnson PF, Weiss KB. Report of the SI2025 Task Force. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(suppl 6):11–57. doi: 10.4300/1949-8349.9.6s.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asch DA, Nicholson S, Srinivas S, Herrin J, Epstein AJ. Evaluating obstetrical residency programs using patient outcomes. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1277–1283. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phillips RL, Jr, Petterson SM, Bazemore AW, Wingrove P, Puffer JC. The effects of training institution practice costs, quality, and other characteristics on future practice. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(2):140–148. doi: 10.1370/afm.2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nasca TJ. Professionalism and its implications for governance and accountability of graduate medical education in the United States. JAMA. 2015;313(18):1801–1802. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.3738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schroeder SA. Shattuck lecture. We can do better—improving the health of the American people. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(12):1221–1228. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa073350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]