Abstract

Objectives:

Despite research documenting significant health disparities among sexual minority women (lesbian, bisexual, and other non-heterosexual women) in high-income countries, few studies of sexual minority women’s health have been conducted in low- and middle-income countries. The purpose of this scoping review was to examine the empirical literature related to the health disparities and health needs of sexual minority women in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), and to identify research gaps and priorities.

Design:

A scoping review methodology was used.

Data sources:

We conducted a comprehensive search of seven electronic databases. The search strategy combined keywords in three areas: sexual minority women, health, and LAC. English, Spanish, and Portuguese language studies published through 2017 in peer-reviewed journals were included.

Review methods:

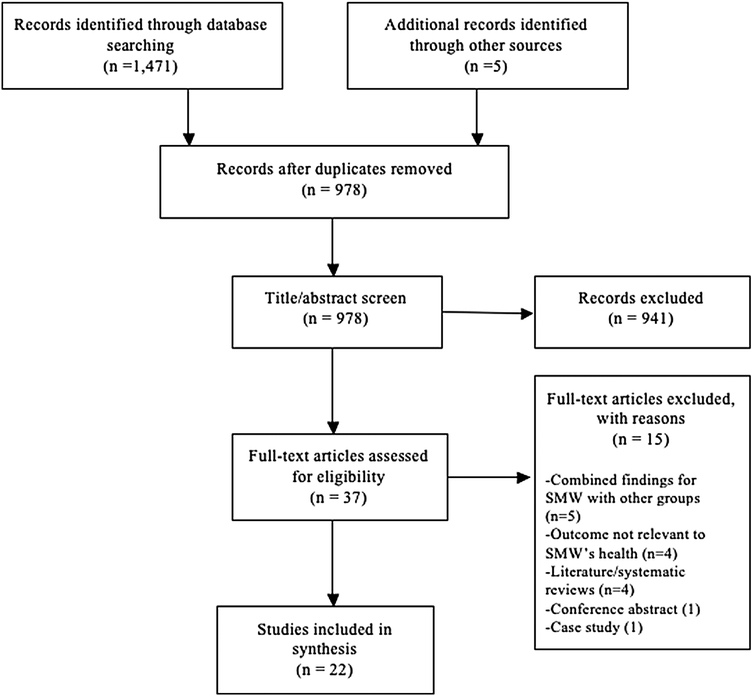

A total 1471 articles were retrieved. An additional 5 articles were identified following descendancy search; 3 of these met inclusion criteria. After removal of duplicates and title and abstract screening, we screened the full text of 37 articles, of which 22 (representing 18 distinct studies) met inclusion criteria. At least two authors independently reviewed and abstracted data from all articles.

Results:

More than half of the studies were conducted in Brazil (n = 9) and Mexico (n = 5). Sexual health was the most studied health issue (n = 11). Sexual minority women were at elevated risk for sexually transmitted infections related to low use of barrier contraceptive methods during sexual encounters with men. Findings suggest that sexual minority women are generally distrustful of healthcare providers and view the healthcare system as heteronormative. Providers are believed to lack the knowledge and skills to provide culturally competent care to sexual minority women. Sexual minority women generally reported low levels of sexual health education and reluctance in seeking preventive screenings due to fear of mistreatment from healthcare providers. Sexual minority women also reported higher rates of poor mental health, disordered eating, and substance use (current tobacco and alcohol use) than heterosexual women. Gender-based violence was identified as a significant concern for sexual minority women in LAC.

Conclusions:

Significant knowledge gaps regarding sexual minority women’s health in LAC were identified. Additional investigation of understudied areas where health disparities have been observed in other global regions is needed. Future research should explore how the unique social stressors sexual minority women experience impact their health. Nurses and other healthcare providers in the region need training in providing culturally appropriate care for this population.

Keywords: Sexual minority women, Women’s health, Latin America and the Caribbean, health disparities

1. Introduction

Leading health organizations worldwide (Australian Human Rights Commission, 2014; Institute of Medicine, 2011; National Institutes of Health, 2015; Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2018; The World Bank, 2017; World Health Organization, 2013) have recently focused on promoting the health of sexual minority women (SMW; lesbian, bisexual, and other nonheterosexual). Multiple studies have documented significant health disparities among SMW in high-income countries such as higher rates of tobacco use (Clark et al., 2016; Kerr et al., 2015; McCabe et al., 2017; Meads et al., 2007), heavy drinking (Hughes et al., 2010a, 2010b, 2010c), obesity (Caceres et al., 2017, 2018; Eliason et al., 2015), breast cancer (Austin et al., 2012; Boehmer et al., 2014), hyperglycemia (Caceres et al., 2018; Kinsky et al., 2016), and poor mental health (Plöderl and Tremblay, 2015; Semlyen et al., 2016; Steele et al., 2009). SMW also report higher rates of violence/victimization (Drabble et al., 2013; Katz-Wise and Hyde, 2012; Szalacha et al., 2017), greater mistrust of healthcare providers (Brotman et al., 2003; Hart and Bowen, 2009) and lower use of preventive services (Dilley et al., 2010; Qureshi et al., 2018) that can potentially impair their wellbeing.

In 2011, the Institute of Medicine in the United States released a report that highlighted high rates of discrimination and victimization experienced by SMW (Institute of Medicine, 2011). In 2013, the World Health Organization identified the need to address minority stressors (e.g., institutionalized prejudice, social exclusion, and anti- homosexual violence) to improve the health and wellbeing of sexual minorities globally (World Health Organization, 2013). These stressors, attributable to sexual minority status, are posited to contribute to poor health outcomes(Meyer, 2003). Despite a growing understanding of the health needs of SMW in the United States and other high-income countries, we know little about the health of SMW living in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

The intersections of homophobic and sexist attitudes in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) make SMW particularly vulnerable to social stress and its associated health risks, particularly those who do not conform to traditional gender roles and feminine appearance (Costa et al., 2013). In LAC gender roles and expectations are strongly shaped by cultural beliefs. Less than one in four women in Latin America feel that women in their countries are treated with respect (Gallup, 2015). In 2017, the United Nations determined LAC as the most violent region in the world, outside confiict contexts, for women (United Nations Development Program, 2017). In fact, LAC was identified as having the highest rate of sexual violence against women (United Nations Development Program, 2017). Further, 14 out of the 25 countries with the highest rates of female violent deaths are located in LAC (Widmer and Pavesi, 2016). This is particularly relevant to SMW who may challenge gender stereotypes and, therefore, become targets of bias-motivated discrimination and violence.

Acceptance of sexual minorities varies greatly across LAC. Same-sex sexual behavior among men is criminalized in Guyana and eight countries in the Caribbean, six of these counties also criminalize same-sex behavior among women (International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, 2017a; Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and Organization of American States, 2015). Decriminalization of same-sex behavior is a recent phenomenon in some countries in LAC with four countries (Belize, Nicaragua, Panama, and Trinidad and Tobago) eliminating criminalization of same-sex behavior within the past decade. Further, two recent studies found high levels of negative attitudes towards sexual minorities in the Caribbean (Beck et al., 2017)— substantially higher than other regions in the Americas (International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association, 2017b). For instance, individuals from the Caribbean were more likely than those in Central and South America to: 1) oppose equal rights for sexual minorities (19%), 2) support criminalization of same-sex sexual activity (22%), and 3) feel uncomfortable socializing with sexual minorities (27%) (International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association, 2017b). A recent study conducted in eight Latin American countries found that older adults (age 60 or older), male participants, those with fewer years of formal education, and participants who were more religious expressed more negative attitudes toward older gay/lesbian individuals (Villar et al., 2018). Further, prejudicial attitudes towards sexual minorities are present across age groups. Approximately 34% of adolescents surveyed across six countries in LAC believed homosexuality should be considered a mental illness (Chaux and León, 2016). Attitudes toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people varied substantially across these six countries with Mexican adolescents reporting more positive attitudes towards sexual minorities than those from the Dominican Republic and Guatemala (Chaux and León, 2016). Yet, a recent study in Mexico indicated that 43% of those surveyed expressed unwillingness to live in the same household with a sexual minority individual (National Council to Prevent Discrimination, 2010). Despite these high rates of negative attitudes, acceptance of sexual minorities remains higher in LAC than in Asia and Africa (International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, 2017b).

Although homophobic and sexist attitudes may be higher in LAC than in many parts of the world (International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association, 2017b), few studies have examined the health status or health needs of SMW in this region. Tat et al. (2015) conducted a systematic review of studies on the sexual health of women who have sex with women (WSW) in LMICs. The authors identified increased risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV, in Brazilian SMW that was primarily related to engaging in sexual activity with men without using safer sex practices (Tat et al., 2015). With the exception of sexual health, little is known about the health of SMW living in LAC. Alencar Albuquerque et al. (2016) conducted a systematic review of 14 studies to examine barriers to healthcare use among sexual and gender minorities. Most of the studies were conducted in the United States with limited representation from studies in LAC. In addition, SMW were underrepresented in comparison to sexual minority men (SMM) (Alencar Albuquerque et al., 2016). Similarly, a systematic review investigating suicide risk in LGBT people identified 45 relevant studies. The majority of studies were conducted in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia, with only two studies conducted in Mexico (Tomicic et al., 2016).

As the largest healthcare profession worldwide nurses play a significant role in reducing health disparities among vulnerable populations, including SMW. Nurses provide over 90% of all health services globally (Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization, 2016) and use a holistic approach to care, which emphasizes health promotion and disease prevention (De Bortoli Cassiani and Zua, 2014). Given the significant impact of social and economic determinants on health and wellbeing, nurses should be competent in identifying and mitigating factors that threaten the health and wellbeing of vulnerable populations (Wilson et al., 2016, 2012). Few studies in LAC have examined the role of nurses in providing care to LGBT patients. However, a recent study conducted in Brazil found that LGBT persons generally mistrust healthcare providers and believe they lack the appropriate expertise to provide culturally tailored care for the LGBT population (Moscheta et al., 2016).

The context in which SMW in LAC live creates unique health risks in this population that remain poorly understood. Although SMW are underrepresented in health research overall (Boehmer, 2002; Coulter et al., 2014), even less attention has been paid to SMW’s health in LMICs. Therefore, the purpose of this scoping review was to examine the empirical literature related to the health disparities and health needs of SMW in LAC with the overarching goal of identifying gaps and priorities to guide future research.

2. Materials and methods

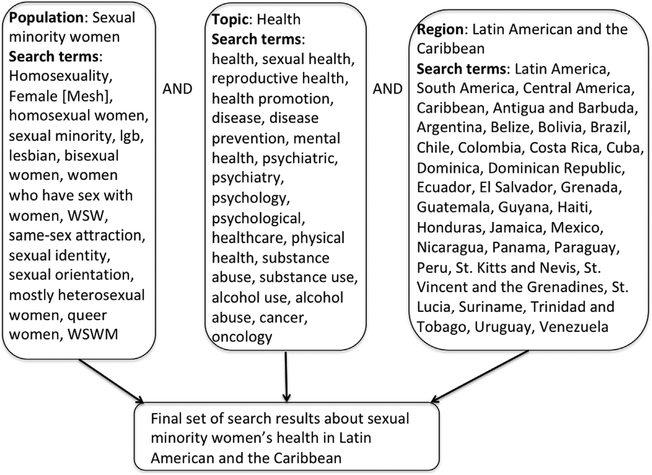

We conducted a search of the empirical literature published through 2017 in seven electronic databases: PubMed, Scielo, LILACS, PsycINFO, LGBT Life, Embase, and CINAHL. These databases were chosen with the help of an informationist at our health sciences library to provide the most comprehensive coverage of relevant studies conducted in LAC. The search strategy combined search terms in three categories: the population of interest (SMW), the topic of interest (health), and the geographic region of interest (LAC) (Fig. 1). Search terms for SMW included various phrases used to describe this population in health sciences research (e.g., lesbian, bisexual, women who have sex with women). Search terms for health topics included health, physical health, mental health, violence, sexual health, reproductive health, and substance use. Search terms for LAC included the names of all countries in this region according to the World Bank (The World Bank, 2018). Search terms within each category were combined using the Boolean operator “or.” Then the search results across the three categories were combined using the Boolean operator “and.” Ancestry and descendancy search of retrieved studies was performed to identify additional articles.

Fig. 1.

Search Strategy.

Inclusion criteria were empirical studies about SMW’s health published in peer-reviewed journals in English, Spanish, or Portuguese. Studies that included both SMW and SMM were included if they reported findings separately by gender. We excluded systematic/literature reviews, articles that reported on psychometric development and testing, healthcare professionals’ views about sexual minorities, prevalence estimates of sexual minority populations, studies conducted with Latino migrants or refugees in a non-Latin American country, conference abstracts, case studies, and reports in the grey literature. We screened all titles and abstracts after completing the ancestry and descendancy search. Two authors then reviewed the full text of each article. Data were abstracted if the article met inclusion criteria. Any disagreements between these two authors were discussed with a third author until consensus was achieved.

We created and used data extraction matrices to summarize key features of the studies. Categories in the data extraction matrices were country/countries where the research was conducted, population(s) included in the study, first author/year, study design, objectives, recruitment strategy, sample characteristics, and key findings.

3. Results

Our search yielded a total of 1471 articles as shown in the PRISMA diagram (Fig. 2). An additional 5 articles were identified following descendancy search; 3 of these met inclusion criteria. After removal of duplicates and title and abstract screening, we screened the full text of 37 articles, of which 22 met inclusion criteria.

Fig. 2.

PRISMA A FLOW Diagram.

Table 1 summarizes study characteristics for the 22 included articles (representing 18 distinct studies). Although the inclusion criteria did not set limits on earliest publication dates, the earliest studies included were conducted in 2005. The majority of studies were conducted in Brazil (n = 9), followed by Mexico (n = 5), Argentina (n = 3), and Chile (n = 2). We found one study in each of the following countries: Colombia, Guyana, and St. Lucia (Fig. 3). Two studies included samples from multiple countries. Bloomfield et al. (2011) included participants from several Latin American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Uruguay) and a study by Traeen et al. (2009) included participants from Cuba as well as other countries outside the LAC region. In terms of study design, the majority of the studies (n = 13) used quantitative methods; 6 were qualitative, and 3 used mixed method approaches. All studies used a cross-sectional design. Nearly all of the studies used non-probability sampling methods (e.g., convenience, purposive, and snowball); only one study used a representative sample (Ortiz-Hernández et al., 2009). Sample sizes ranged widely, from six to 1484 participants with authors of two articles not reporting their sample sizes (Mertehikian, 2017; Mora and Monteiro, 2010). The age of participants also varied across studies. Only two studies focused solely on sexual minority adolescents (Diaz Montes et al., 2005; Ortiz-Hernández et al., 2009). Four studies included both adolescent and adult participants (Anaid Ramörez-Aguilar et al., 2016; Ortiz-Hernández, 2005; Ortiz-Hernández and García Torres, 2005; Ortiz-Hernández and Granados-Cosme, 2006) and the remaining studies included only individuals who were age 18 or older. No studies focused exclusively on sexual minority older adults. With the exception of a study conducted in Guyana (Rambarran and Simpson, 2016), the remaining studies did not mention whether transgender women (who identify as a woman and were assigned the male sex at birth) were included in their samples.

Table 1.

Study characteristics.

| First Author, Year | Study Design | Recruitment Strategy | Location | Sample | Age Range or Mean | Sexual Orientation Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaid Ramírez-Aguilar et al., 2016. | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Mexico | 73 (including 15 lesbian women, 15 bisexual women, and 13 gay men) | 16–30 years | Sexual identity |

| Bahamondes-Correa, 2016*** | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Chile | 467 (268 gay men and 199 lesbian women) | 18–67 years | Sexual identity |

| Barbosa and Facchini, 2009 | Qualitative: ethnography and in-depth interviews | Convenience | Brazil | 30 women who have sex with women | 18–45 years | Sexual identity |

| Barrientos et al., 2017*** | Cross-sectional | Snowball | Chile | 447 (191 lesbian women, 256 gay men) | 18–67 years | Sexual identity |

| Bloomfield et al., 2011 | Secondary analysis of data from the Gender, Alcohol, and Culture: An International Study (GENACIS) which | Differed by country | International (Latin American countries included: Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Uruguay) | 3968 adult participants (122 lesbians, 126 gay men, 1830 heterosexual women, 1890 heterosexual men) | Over 18 years old | Gender of romantic partner |

| Calado Dantas et al., 2016. | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews | Convenience | Brazil | 6 lesbian women | 20–23 years | Sexual identity |

| Couzens et al., 2017. | Qualitative: semi structured interviews | Purposive | St. Lucia | 9 sexual minority women and men | 18–46 years | Sexual identity |

| da Silva Oliveira et al., 2017. | Cross-sectional | Snowball | Brazil | 91 women who have sex with women | 26–33 years | Sexual behavior |

| de Lima Garcia et al., 2016. | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews | Snowball | Brazil | 30 (6 lesbian, 3 bisexual, 12 gay, 9 transgender [gender identity not reported]) | 18–51 years | Sexual identity |

| Diaz Montes el: al., 2005. | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Colombia | 432 participants (213 girls and 42 identified as gay/lesbian, bisexual or questioning) | 13–17 years | Sexual identity |

| Gomes de Carvalho et al., 2013. | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews | Convenience | Brazil | 9 SMW | 25–40 years | Sexual identity |

| Mertehikian, 2017. | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews | Snowball | Argentina | Not reported | 18–29 years | Sexual identity |

| Monteiro et al., 2010.* | Mixed methods; interviews and questionnaires | Convenience | Brazil | 72 sexual minorities (no breakdown by sexual orientation) | 18–26 years | Not specified |

| Mora and Monteiro, 2010.* | Mixed methods: ethnography, in-depth interviews, and questionnaires | Convenience | Brazil | Not reported | 18–26 years | Sexual behavior |

| Ortiz-Hernández, 2005.** | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Mexico | 506 sexual minorities (188 lesbian and bisexual women, 318 gay and bisexual men) | 13–70 years | Attraction, sexual behavior, and identity |

| Ortiz-Hernández and García Torres, 2005.** | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Mexico | 506 sexual minorities (188 lesbian and bisexual women, 318 gay and bisexual men) | 13–70 years | Attraction, sexual behavior, and identity |

| Ortiz-Hernández and Granados-Cosme, 2006.** | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Mexico | 506 sexual minorities (188 lesbian and bisexual women, 318 gay and bisexual men) | 13–70 years | Attraction, sexual behavior, and identity |

| Ortiz-Hernandez, et al., 2009. | Secondary analysis of the 2005 National Youth Survey | Probability | Mexico | 12,796 participants (1484 same-sex attracted, 179 reported same-sex behavior, 230 identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual) | 12–29 years | Attraction, sexual behavior, and identity |

| Pinto et al., 2005. | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Brazil | 145 women who have sex with women | 18–50+ years | Sexual behavior |

| Rambarran and Simpson, 2016. | Qualitative: semi structured interviews | Convenience | Guyana | 16 SMW | 20–40+ years | Sexual identity |

| Silberman et al., 2016. | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Argentina | 161 women who have sex with women | Mean age: 29.3 years | Sexual behavior |

| Traeen et al., 2009 | Cross-sectional | Convenience | International (Cuba, India, South Africa, and Norway) | 872 participants (337 from Cuba of which 29 identified as gay/lesbian, bisexual or questioning) | 20–40+ years | Sexual identity |

Note. The 22 included articles represent 18 distinct studies.

Monteiro et al. (2010) and Mora and Monteiro (2010) reported findings from the same study.

Ortiz-Hernández (2005),Ortiz-Hernández and García Torres (2005), and Ortiz-Hernández and Granados-Cosme (2006) reported findings from the same study.

Bahamondes-Correa (2016) and Barrientos et al. (2017) reported findings from the same study.

Fig. 3.

Included Studies by Location.

Sexual orientation was most commonly defined using measures of sexual identity (n = 12) and sexual behavior (n = 4). One study asked about gender of romantic partners (n = 1) as a proxy for sexual orientation. Four studies conducted by Ortiz-Hernández and colleagues used multiple dimensions (attraction, behavior, and identity) to assess sexual orientation (Ortiz-Hernández, 2005; Ortiz-Hernández et al., 2009; Ortiz-Hernández and García Torres, 2005; Ortiz-Hernández and Granados-Cosme, 2006). The remaining study (Monteiro et al., 2010) did not operationally define sexual orientation.

Study findings are summarized in Table 2. The majority of studies focused on sexual health (n = 11). Fewer focused on mental health (n = 8), substance use (n = 5), violence and/or marginalization (n = 4), or healthcare experiences (n = 6). One study focused on cognitive function. Some studies focused on more than one of these topical areas. Below we review the key findings organized by topic (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of study findings.

| First Author, Year | Objective | Key Findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaid Ramírez-Aguilar et al., 2016. | Investigate sex and sexual orientation differences in cognitive function among young adults. |

|

|||

| Bahamondes-Correa, 2016*** | Test the effects of system justification beliefs on psychological distress (anxiety and depression symptoms) and examine the mediating role of internalized homonegativity among gay and lesbian individuals. |

|

|||

| Barbosa and Facchini, 2009 | Explore perceptions of the relationship between access to healthcare and representations of gender and sexuality, among women who have sex with women. |

|

|||

| Barrientos et al., 2017*** | Assess the mental health and wellbeing of Chilean gay men and lesbian women. |

|

|||

| Bloomfield et al., 2011 | Examine the prevalence of high-volume and binge drinking in gay men and lesbians compared to heterosexuals in a large international study of gender, alcohol and culture. |

|

|||

| Calado Dantas et al., 2016. | Describe gender-based violence in lesbian women in same-sex relationships. |

|

|||

| Couzens et al., 2017. | Explore experiences of homophobia among lesbian, gay, and bisexual people in St. Lucia. | Two themes emerged:

|

|||

| da Silva Oliveira et al., 2017. | Evaluate knowledge, attitudes and practices related to the prevention and transmission of HIV/AIDS in women who have sex with women. |

|

|||

| de Lima Garcia el al., 2016. | Investigate perceptions of health and social inequities experienced by lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals when accessing healthcare. |

|

|||

| Diaz Montes et al., 2005. | Assess the association between the sexual orientation and depressive symptoms in adolescents. |

|

|||

| Gomes de Carvalho et al., 2013. | Identify the perception of lesbian and bisexual women regarding healthcare services and prevention of STIs. |

|

|||

| Mertehikian, 2017. | Describe the sexual and reproductive healthcare practices of lesbian and bisexual women. | Three themes emerged:

|

|||

| Monteiro et al., 2010.* | Examine the role of sexual identity and gender on representations and practices of risk and protection against STIs and HIV. |

|

|||

| Mora and Monteiro, 2010.* | Explore the vulnerability of women who have sex with women to STIs and HIV in Brazil. |

|

|||

| Ortiz-Hernández, 2005.** | Identify whether minority stressors were associated with worse mental health (suicidal ideation, past suicide attempts, poor mental health, and alcoholism) among sexual minorities. |

|

|||

| Ortiz-Hernández and Garria-Torres, 2005.** | Estimate the prevalence of suicidal ideation, suicide at- tempts, mental disorders, and alcoholism in bisexuals, lesbians, and gays in Mexico City and identify discrimination and violence as risk factors for poor mental health in this population. |

|

|||

| Ortiz-Hernández and Granados-Cosme, 2006.** | Examine the prevalence of violence against bisexual, lesbian, and gay people. |

|

|||

| Ortiz-Hernandez, et al., 2009. | Analyze mediators and moderators of the relationship between sexual orientation, self-rated health, and cigarette and alcohol use among Mexican youth. |

|

|||

| Pinto et al., 2005. | Describe prevalence of STIs in women who have sex with women and identify behavioral factors associated with the presence of STIs in this population. |

|

|||

| Rambarran and Simpson, 2016. | Explore how Guyanese SMW experience healthcare interactions. |

|

|||

| Silberman et al., 2016. | Describe barriers to sexual healthcare for women who have sex with women. |

|

|||

| Traeen et al., 2009 | Examine differences in quality of life among heterosexual men and women, and lesbian/gay and bisexual university students four countries. |

|

|||

Note. The 22 included articles represent 18 distinct studies.

Monteiro et al. (2010) and Mora and Monteiro (2010) reported findings from the same study.

Ortiz-Hernández (2005), Ortiz-Hernández and García Torres (2005), and Ortiz-Hernández and Granados-Cosme (2006) reported findings from the same study.

Bahamondes-Correa (2016) and Barrientos et al. (2017) reported findings from the same study.

3.1. Sexual health

As noted above, 11 studies focused on sexual health, specifically risk for HIV or other STIs. The majority (n = 7) of these studies were conducted in Brazil. Two studies explored perceptions of STI risk in SMW. Lesbian women identified themselves as having low risk for HIV compared to heterosexual women (Monteiro et al., 2010), but recognized a heightened risk of HIV when having sex with bisexual women or with men (Mora and Monteiro, 2010). However, both lesbian and bisexual women had few concerns regarding risk for STIs and HIV (Monteiro et al., 2010). Pinto et al. (2005) examined the prevalence of STIs among 145 Brazilian women who reported having had same-sex relationships. The prevalence rates of human papilloma virus (6.2%), chlamydia (1.8%), and HIV (2.9%) were low. Of the participants who reported having a male sexual partner in the past year (23.4%), less than half used condoms during sexual encounters (Pinto et al., 2005). Similarly, 77.5% of SMW in a cross-sectional study conducted in Argentina reported not using any barrier protection (e.g., dental dams) during sexual encounters with women (Silberman et al., 2016). da Silva Oliveria et al. (2017) investigated knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to HIV risk in 94 WSW in Brazil. They found that approximately two-thirds of study participants had adequate knowledge of HIV prevention and treatment (da Silva Oliveira et al., 2017). In contrast, in a study of SMW in Argentina, Silberman et al. (2016) found that less than half of the study participants felt they had adequate knowledge of STI prevention.

Findings from the studies included in this review suggest that SMW receive little information about sexual health from healthcare providers (Diaz Montes et al., 2005; Mertehikian, 2017; Silberman et al., 2016). A study conducted in Chile among adolescents (ages 13–17) found that sexual minority girls were nearly three times as likely as heterosexual girls to report not receiving adequate sexual health education (Diaz Montes et al., 2005). Silberman et al. (2016) also found that SMW in Argentina had low rates of receiving sexual health education. In this study, more than 90% of participants reported never receiving STI information from a healthcare provider. Overall, SMW in Argentina reported obtaining sexual health information from friends and/or Internet sources (Mertehikian, 2017; Silberman et al., 2016).

3.2. Mental health

Among the studies that examined mental health, three were conducted in Mexico, two in Chile, and the remaining three studies were conducted in Colombia, Cuba, and St. Lucia. Diaz Montes et al. (2005) found that sexual minority adolescent girls in Colombia had significantly higher rates of depressive symptoms (OR = 1.10, 95% CI 1.01–1.18) and higher scores on a validated eating disorder questionnaire (OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.05–2.40) relative to heterosexual girls. Similarly, SMW in Mexico were more likely than their heterosexual counterparts to report poor mental health (Ortiz-Hernández, 2005; Ortiz-Hernández and García Torres, 2005). Although SMW in Mexico reported higher rates of past suicide attempts than SMM (Ortiz-Hernández, 2005), a study in Chile found they had lower rates of current suicide intent than SMM (Barrientos et al., 2017). An additional study in Chile investigated the impact of system justification (defined as the belief that oppression of sexual minorities in society is justified) on anxiety and depressive symptoms in sexual minorities (Bahamondes-Correa, 2016). Results of multivariate analyses showed that system justification was associated with increased anxiety and depressive symptoms among SMM, but not among SMW (Bahamondes-Correa, 2016). Another report of findings from the same study found that SMW reported higher levels of life satisfaction (p<0.01) and better interpersonal relationships than SMM (p<0.001) (Barrientos et al., 2017). Anaid Ramirez-Aguilar et al. (2016) investigated differences in anxiety and depressive symptoms among adolescents and young adults in Mexico. Bisexual women had higher scores on both the Beck Anxiety and Beck Depression Inventories than lesbian women, but not heterosexual women. No differences were noted between lesbian and heterosexual women. Furthermore, a qualitative study conducted in St. Lucia (n = 9) identified perceived consequences of marginalization of sexual minorities on their health. Participants identified depression, anxiety, fear, and social isolation as possible consequences (Couzens et al., 2017). Træen et al. (2009) assessed differences in quality of life among sexual minority and heterosexual college students in Cuba, India, South Africa, and Norway. Findings were reported separately by country. Approximately 38.6% of the total 872 participants were recruited from Cuba, of which 29 identified as sexual minorities (11 women and 18 men). Despite the small sample size the researchers found that SMW reported significantly higher fear and anger relative to heterosexual women.

3.3. Substance use

A total of five studies examined substance use among SMW in LAC. Sexual minority adolescent girls in Mexico reported significantly higher rates of current tobacco use and alcohol use than their heterosexual counterparts (Ortiz-Hernández et al., 2009). These disparities in substance use were primarily explained by experiences of discrimination and violence. Approximately 21% of SMW in a study conducted in Mexico met criteria for alcoholism using the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) (Ortiz-Hernández and García Torres, 2005). Also, sexual minority adolescent girls in Colombia reported significantly greater illicit drug use compared to heterosexual girls (OR 6.21, 95% CI 1.24–31.30) (Diaz Montes et al., 2005). SMW in Pinto and colleagues’ (2005) study reported frequent use of tobacco (46.9%), alcohol (62.1%), marijuana (40.2%), and cocaine (16.1%) in the past year, but no participants reported use of injection drugs. Bloomfield et al. (2011) analyzed international data from the Gender, Alcohol, and Culture Study (GENACS)to examine sexual orientation differences in the prevalence of high-volume drinking and binge drinking. Although GENACS was conducted in five Latin American and Caribbean countries (including Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Uruguay), only 21 women from this region were identified as sexual minority and no differences in alcohol use were observed between SMW and heterosexual women (Bloomfield et al., 2011).

3.4. Violence/Marginalization

A total of four studies examined violence and/or marginalization in SMW. A qualitative study conducted in Brazil explored lesbian women’s (n = 6) perceptions of gender-based violence in their country (Calado Dantas et al., 2016). Participants’ narratives emphasized the significant role that gender-based violence played in their lives, including corrective rape perpetrated by male family members. They also reported believing that healthcare providers lacked an understanding of health issues that affect lesbian women and were unprepared to address intimate partner violence that occurred in lesbian relationships (CaladoDantasetal.,2016).Ortiz-Hernándezand Granados-Cosme (2006) found that SMW and SMM in Mexico reported high rates of violence during childhood, primarily attributed to their non-conformity to ascribed gender roles; SMM were more likely than SMW to report such experiences. SMW most frequently identified their mothers as perpetrators of violence during childhood (Ortiz-Hernández and Granados-Cosme, 2006). In addition, SMW in Mexico were more likely than SMM to report experiencing childhood physical abuse (Ortiz-Hernández and García Torres, 2005). Lastly, SMW in St. Lucia described the pervasive influence of discrimination on their everyday life and how skin color contributes to unequal treatment of the sexual minority community (Couzens et al., 2017). Participants believed there is greater tolerance for light-skinned sexual minorities in St. Lucia and that dark-skinned sexual minorities are less accepted. A dark-skinned lesbian participant reported she had become socially isolated due to fear of experiencing discrimination. Overall, participants identified that higher levels of education as a buffer of discrimination as well as a means to greater financial opportunities in society (Couzens et al., 2017).

3.5. Healthcare experiences

Although only two studies, Mertehikian (2017) and Silberman et al. (2016), focused on sexual healthcare, participants in five out of six studies that assessed healthcare experiences of SMW exclusively discussed these encounters in relation to sexual health. Nearly one-quarter of SMW in a study conducted in Brazil had never had a Pap test (Barbosa and Facchini, 2009). SMW in this study were more likely to identify as having masculine attributes (Barbosa and Facchini, 2009). Thus, SMW in Brazil generally reported they had little need for gynecological care (Barbosa and Facchini, 2009; de Lima Garcia et al., 2016). Moreover, in a sample of 161 women in Argentina the majority of participants reported visiting a healthcare provider in the past year, but only a small number (17.2%) indicated that their healthcare providers had asked them their sexual orientation (Silberman et al., 2016). A qualitative study of 16 SMW in Guyana explored interactions with the healthcare system (Rambarran and Simpson, 2016). Participants generally reported that healthcare providers rarely discussed sexual health with them (Mertehikian, 2017; Rambarran and Simpson, 2016). They felt that healthcare providers pathologize sexual minorities and that healthcare settings were heteronormative—the assumption that all patients are heterosexual or belief that being heterosexual is preferred over other sexual orientations (Barbosa and Facchini, 2009; Mertehikian, 2017; Rambarran and Simpson, 2016; Silberman et al., 2016). SMW in several studies indicated that they feared disclosing their sexual orientation to healthcare providers and felt vulnerable in healthcare encounters (Barbosa and Facchini, 2009; Gomes de Carvalho et al., 2013; Rambarran and Simpson, 2016). They also felt that healthcare providers lacked the knowledge to provide adequate care to SMW (Gomes de Carvalho et al., 2013; Mertehikian, 2017). These factors were cited as reasons for infrequent use of healthcare services.

3.6. Cognitive function

One study conducted in Mexico investigated sex and sexual orientation differences in cognitive function (e.g., memory, attention) among 73 adolescent and young adult participants (ages 16–30) (Anaid Ramírez-Aguilar et al., 2016). No significant sex and/or sexual orientation differences were noted.

4. Discussion

Findings from this review underscore the substantial sexual orientation-related health risks and health disparities among SMW in LAC and allowed us to identify many knowledge gaps regarding the health of SMW in this region. As the first review to focus exclusively on the health of SMW in this geographic region, our findings provide important directions for future research and opportunities to improve SMW’s health in LAC.

Sexual health was the most prominent health issue examined. Our results corroborate the work of Tat et al. (2015) who found that WSW in LMICs report high rates of risky sexual behaviors. SMW in the current review were at increased risk of STIs primarily related to low use of barrier contraceptive methods during sexual encounters with men (da Silva Oliveira et al., 2017; Mora and Monteiro, 2010; Pinto et al., 2005). Our findings are also consistent with the results of two previous studies that found similar rates of low condom use among SMW from China and the United States (Wang et al., 2012; Ybarra et al., 2016). Results are contradictory regarding knowledge of sexual health with SMW in Brazil reporting high levels of STI knowledge (da Silva Oliveira et al., 2017; Gomes de Carvalho et al., 2013) and those in Argentina and Colombia reporting low levels (Diaz Montes et al., 2005; Silberman et al., 2016). Therefore, our findings highlight the need for sexual health education to reduce the sexual health risks observed among SMW in this world region. Although the majority of included studies that examined sexual health focused on STIs, it is important to note that sexual health encompasses other concerns (e.g., sexual dysfunction, reproductive choices) (World Health Organization, 2014). More research is needed that examines other aspects of sexual health in SMW living in LAC in addition to STI risk and prevention.

SMW in the included studies were reluctant to engage with the healthcare system. Participants indicated that the approach to gynecological care was heteronormative and they were uncomfortable when seeking such care (Barbosa and Facchini, 2009; Mertehikian, 2017; Rambarran and Simpson, 2016; Silberman et al., 2016). Discomfort with the healthcare system has also been found among sexual minorities in other parts of the world. For example, Gowen and Winges-Yanez (2014) found that sexual minority youth in the United States view sexual health education as unresponsive to the needs of sexual minorities. Further, SMW in Brazil reported lower rates of Pap tests and gynecological care in the past year (Barbosa and Facchini, 2009), which is consistent with evidence from the United States (Buchmueller and Carpenter, 2010; Kerker et al., 2006) and France (Chetcuti et al., 2013). Perceived lower risk of STIs reported by participants in two studies (Monteiro et al., 2010; Mora and Monteiro, 2010) is similar to findings from a recent analysis of data from the National Survey of Family Growth in the United States (Agénor et al., 2017). The studies included in this review that examined healthcare experiences of SMW focused mostly on sexual health. However, it appears SMW believe nurses and other healthcare providers in LAC lack the skills to provide culturally competent care, particularly as it relates to sexual health.

Adolescent and young SMW in the studies reviewed were more likely than their heterosexual peers to report substance use and poor mental health (Diaz Montes et al., 2005; Ortiz-Hernández, 2005; Ortiz-Hernández and García Torres, 2005). Sexual minority adolescent girls in one of the studies reported higher levels of depressive symptoms than a comparison group of heterosexual girls (Diaz Montes et al., 2005). These researchers also found that sexual minority adolescent girls had higher scores than heterosexual girls on a validated eating disorder questionnaire. In the United States there is contradictory evidence regarding sexual orientation differences in eating disorders, with some evidence suggesting SMW have higher rates of disordered eating compared to heterosexual women (Austin et al., 2013; Mor et al., 2015) and others finding no difference (Feldman and Meyer, 2007). Research on substance use among SMW in LAC is limited, especially in light of higher rates of tobacco and heavy drinking reported in the few studies we found on this topic (Ortiz-Hernández et al., 2009; Ortiz-Hernández and García Torres, 2005). Similarly, Diaz Montes et al. (2005) found sexual minority adolescent girls in Colombia reported higher rates of illicit drug use relative to heterosexual girls, which corroborates data from the United States (Corliss et al., 2010; Marshal et al., 2012).

Nurses and other healthcare providers in LAC should be educated about health issues that are prevalent in this population (e.g., poor mental health, substance use). These data indicate that SMW in LAC have specific health concerns (e.g. mental health and substance use) that should be addressed by healthcare providers. Health promotion efforts that target this population should take into account the unique social determinants that impact SMW’s health, however, to achieve this it is necessary to incorporate LGBT content into the education of nurses and other health professions. Further, in order to promote the health of SMW and other vulnerable populations there is a need to strengthen public health nursing education in LAC as most nursing education has focused on acute care services (Joyce et al., 2017).

The 22 articles included in this review highlight the impact of minority stress (e.g., victimization, discrimination) on the health of SMW. Participants in Calado Dantas et al. (2016) study identified gender-based violence as a common concern of SMW. Corrective rape has been described as a major health issue for SMW in South Africa (Muller and Hughes, 2016) and in other parts of the world (Bhalla, 2015; South China Morning Post, 2018). Only one study in the present review discussed corrective rape as an issue for SMW in Brazil. Therefore, the extent of this practice in LAC is unknown. SMW in Mexico reported higher rates of violence across the lifecourse (Ortiz-Hernández and García Torres, 2005; Ortiz-Hernández and Granados-Cosme, 2006), which is consistent with evidence from a recent meta-analysis of 65 studies conducted in several nations (including the United States, England, South Africa, and Netherlands) (Katz-Wise and Hyde, 2012). Overall, there is a lack of quantitative research examining the association of minority stressors and health among SMW in Latin America. Although several nations in the region, particularly in the Caribbean, criminalize same-sex sexual behavior, little is known about the impact of these policies on the health of SMW. A recent survey of eight countries in LAC found that heterosexual individuals who lived in countries where sexual minorities had greater legal rights (e.g., same-sex marriage, legal adoption by same-sex adoption, and hate crimes based on sexual orientation) reported more positive attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women (Villar et al., 2018). Future studies should investigate the in influence of violence exposure, institutionalized homophobia, and protective policies on the health and wellbeing of SMW in LAC.

Given that older SMW were underrepresented in this review, additional research is needed to determine whether the observed mental health and substance use disparities among SMW persist as they age. This is a significant gap in the extant literature as LAC is expected to experience a 30% increase in their older adult population between 2010–2050 (National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2015).

4.1. Limitations

Although this review of 22 articles provides a baseline understanding about the health of SMW in LAC, several limitations of our review and the studies included in the review should be considered when evaluating the findings. First, because we chose to include only studies published in peer-reviewed journals we missed findings from unpublished research. Despite conducting a comprehensive review of several electronic databases, the studies included in this review were conducted in only ten LAC countries. This limits the generalizability of findings to other countries in the region. All included studies were cross-sectional. The lack of prospective designs makes it difficult to establish causality and identify the impact of minority stressors (e.g., victimization, marginalization, discrimination) on the health of SMW. Given that only one study employed non-probability sampling, the extent or impact of selection bias across studies is unknown. Participants in the studies reviewed may have characteristics and health risks that are different from the larger population of SMW from their respective geographic areas. Most of the studies reviewed had small sample sizes, which further limits the generalizability of findings. There was little discussion regarding heterogeneity in health outcomes across subgroups of SMW (e.g., lesbian vs. bisexual women, racial/ethnic and low-income SMW). Indeed, only Couzens et al. (2017) examined the impact of skin color on experiences of marginalization. Similarly, only one study mentioned inclusion of transgender women who identified as SMW in their sample (Rambarran and Simpson, 2016). Transgender women who may also identify as non-heterosexual may be at particularly high risk for violence and discrimination compared to both other sexual minority and heterosexual women in LAC (Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and Organization of American States, 2015). Therefore, the examination of heterogeneity in health outcomes across subgroups of SMW in LAC is an area in need of further research.

5. Conclusion

In addition to highlighting the nascent body of research on SMW’s health in LAC, this review demonstrates that further research is needed to elucidate the unique health needs of SMW in LAC. Additional research should explore how the social stressors experienced by SMW in LAC impact their health. There is a need for research that examines a wider breadth of health conditions beyond sexual health. Our findings have significant implications for nurses and other healthcare providers in LAC since SMW are reluctant to seek healthcare due to fear of discrimination. Initiatives to increase the ability of healthcare providers in the region to care for SMW’s unique health risks are urgently needed.

What is already known about the topic?

Growing evidence from high-income countries suggests that sexual minority (e.g., lesbian, bisexual, and other non-heterosexual) women experience significant health disparities compared to heterosexual women. However, little is known about the health of sexual minority women living in low- and middle-income countries.

Despite high rates of homophobia and sexual violence against women there has been limited research on the health of sexual minority women in Latin America and the Caribbean.

What this paper adds.

Most research on sexual minority women’s health in Latin America and the Caribbean has focused on sexual health to the exclusion of other health outcomes.

Health disparities (including mental health, substance use, and violence) among sexual minority women in Latin America and the Caribbean are consistent with those observed in the United States and other high-income countries.

Sexual minority women are generally reluctant to seek healthcare and feel healthcare providers lack the knowledge to adequately address their health concerns.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by two institutional training grants at the Columbia University School of Nursing funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research of which Billy A. Caceres (T32NR014205) and Kasey B. Jackman (T32NR007969) are postdoctoral trainees. The sponsor had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing the report, and the decision to submit the report for publication.

References

- Agénor M, Muzny CA, Schick V, Austin EL, Potter J, 2017. Sexual orientation and sexual health services utilization among women in the United States. Prev. Med. (Baltim) 95, 74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alencar Albuquerque G, de Lima Garcia C, da Silva Quirino G, Alves MJH, Belém JM, dos Santos Figueiredo FW, da Silva Paiva L, do Nascimento VB, da Silva Maciel É, Valenti VE, de Abreu LC, Adami F, 2016. Access to health services by lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons: systematic literature review. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 16 (2) doi: 10.1186/s12914-015-0072-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anaid Ramírez-Aguilar M, Calderón GO, Romero Rebollar C, 2016. Cognitive functions in sexual orientation. Rev. Chil. Neuropsicol 11, 30–34. doi: 10.5839/rcnp.2016.11.01.06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Austin SB, Pazaris MJ, Rosner B, Bowen D, Rich-Edwards J, Spiegelman D, 2012. Application of the Rosner-Colditz risk prediction model to estimate sexual orientation group disparities in breast cancer risk in a U.S. cohort of premenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 21, 2201–2208. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin SB, Nelson LA, Birkett MA, Calzo JP, Everett B, 2013. Eating disorder symptoms and obesity at the intersections of gender, ethnicity, and sexual orientation in US high school students. Am. J. Public Health 103, e16–22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Human Rights Commission, 2014. Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Intersex Status Discrimination. NSW, Syndey. [Google Scholar]

- Bahamondes-Correa J, 2016. System justification’s opposite effects on psychological wellbeing: testing a moderated mediation model in a gay men and lesbian sample in Chile. J. Homosex 63, 1537–1555. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2016.1223351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa RM, Facchini R, 2009. Access to sexual health care for women who have sex with women in São Paulo, Brazil. Cad. Saude Publica 25, s291–s300. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2009001400011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos J, Gómez F, Cárdenas M, Gúzman M, Bahamondes J, 2017. Medidas de salud mental y bienestar subjetivo en una muestra de hombres gays y mujeres lesbianas en Chile. Rev. Med. Chil 145, 1115–1121. doi: 10.4067/s0034-98872017000901115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck EJ, Espinosa K, Ash T, Wickham P, Barrow C, Massiah E, Alli B, Nunez C,2017. Attitudes Towards Homosexuals in Seven Caribbean Countries: Implications for an Effective HIV Response Attitudes Towards Homosexuals in Seven Caribbean Countries: Implications for an Effective HIV Response. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1316355org/10.1080/09540121.2017.1316355. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bhalla N, 2015. Film Lifts Lid on “corrective Rape” in Families of Gays in India [WWW Document] URL. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/india-lgbt-rape/interview-film-lifts-lid-on-corrective-rape-in-families-of-gays-in-india-idUSL3N0YW57Z20150611.

- Bloomfield K, Wicki M, Wilsnack S, Hughes T, Gmel G, 2011. International differences in alcohol use according to sexual orientation. Subst. Abus 32, 210–219. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2011.598404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehmer U, 2002. Twenty years of public health research: inclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations. Am. J. Public Health 92, 1125–1130. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.7.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehmer U, Miao X, Maxwell NI, Ozonoff A, 2014. Sexual minority population density and incidence of lung, colorectal and female breast cancer in California. BMJ Open 4, e004461 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman S, Ryan B, Cormier R, 2003. The health and social service needs of gay and lesbian elders and their families in Canada. Gerontologist 43, 192–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmueller T, Carpenter CS, 2010. Disparities in health insurance coverage, access, and outcomes for individuals in same-sex versus different-sex relationships, 2000–2007. Am. J. Public Health 100, 489–495. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.160804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caceres BA, Brody A, Luscombe RE, Primiano JE, Marusca P, Sitts EM, Chyun D, 2017. A systematic review of cardiovascular disease in sexual minorities. Am. J. Public Health 107, e13–e21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caceres BA, Brody AA, Halkitis PN, Dorsen C, Yu G, Chyun DA, 2018. Cardiovascular disease risk in sexual minority women (18–59 years old): findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2001–2012). Women’s Heal. Issues 28, 333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calado Dantas BR, Tavares de Lucena K, de Souza Chaves Deninger L, Garrido de Andrade C, Cleiton Cunha Monteiro A, 2016. Gender violence in lesbian relationships. Rev. Enferm. (Lisboa) 10, 3989–3995. doi: 10.5205/reuol.9881-87554-1-EDSM1011201621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaux E, León M, 2016. Homophobic attitudes and associated factors among adolescents: a comparison of six Latin American countries. J. Homosex 63, 1253–1276. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2016.1151697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetcuti N, Beltzer N, Methy N, Laborde C, Velter A, Bajos N, 2013. Preventive care’s forgotten women: life course, sexuality, and sexual health among homosexually and bisexually active women in France. J. Sex Res. 50, 587–597. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.657264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CJ, Alonso A, Everson-Rose SA, Spencer RA, Brady SS, Resnick MD, Borowsky IW, Connett JE, Krueger RF, Nguyen-Feng VN, Feng SL, Suglia SF, 2016. Intimate partner violence in late adolescence and young adulthood and subsequent cardiovascular risk in adulthood. Prev. Med. (Baltim) 87, 132–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corliss HL, Rosario M, Wypij D, Wylie SA, Frazier AL, Austin SB, 2010. Sexual orientation and drug use in a longitudinal cohort study of U.S. adolescents. Addict. Behav 35, 517–521. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa AB, Peroni RO, Bandeira DR, Nardi HC, 2013. Homophobia or sexism? A systematic review of prejudice against nonheterosexual orientation in Brazil. Int. J. Psychol 48, 900–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter RWS, Kenst KS, Bowen DJ, 2014. Research funded by the National Institutes of Health on the health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations. Am. J. Public Health 104, 105–112. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couzens J, Mahoney B, Wilkinson D, 2017. “It’s just more acceptable to bewhite or mixed raceandgaythanblackandgay”:theperceptionsandexperiencesofhomophobiainSt. Lucia. Front. Psychol 8, 1–16. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Oliveira AD, Sampaio Nery I, Gir E, Evangelista de Araujo TM, de Oliveira Barros Junior F, 2017. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of HIV/AIDS of women who have sex with women. Rev. Enferm. (Lisboa) 11, 2736–2742. doi: 10.5205/reuol.10939-97553-1-RV.1107201712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Bortoli Cassiani SH, Zua KE, 2014. Promoting the advanced nursing practice role in Latin America. Rev. Bras. Enferm 67, 673–674. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167.2014670501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lima Garcia C, Albuquerque GA, Drezett J, Adami F, 2016. Health of sexual minorities in north-eastern Brazil: Representations, behaviours and obstacles. Jpn. J. Hum. Growth Dev. Res 26, 94–100. doi: 10.7322/jhgd.110985. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz Montes CE, Cogollo Milanes Z, Banquez Mendoza J, Luna-Salcedo L, Fontalvo Durango K, Arrieta-Puello M, Campo-Arias A, 2005. Síntomas depresivos y la orientación sexual en adolescentes estudiantes: Un estudio transversal. Med UNAB 8, 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Dilley JA, Wynkoop Simmons K, Boysun MJ, Pizacani BA, Stark MJ, 2010. Demonstrating the importance and feasibility of including sexual orientation in public health surveys: health disparities in the Pacific Northwest. Am. J. Public Health 100, 460–467. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.130336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabble L, Trocki KF, Hughes TL, Korcha RA, Lown AE, 2013. Sexual orientation differences in the relationship between victimization and hazardous drinking among women in the National Alcohol survey. Psychol. Addict. Behav 27, 639–648. doi: 10.1037/a0031486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliason MJ, Ingraham N, Fogel SC, McElroy JA, Lorvick J, Mauery DR, Haynes S, 2015. A systematic review of the literature on weight in sexual minority women. Women’s Heal. Issues 25, 162–175. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman MB, Meyer IH, 2007. Eating disorders in diverse lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Int. J. Eat. Disord 40, 218–226. doi: 10.1002/eat.20360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallup, 2015. Global Law and Order 2015..

- Gomes de Carvalho PM, Martins Nobrega BM, Lima Rodrigues J, Oliveira Almeida R, Tavares de Mello Abdalla F, Yasuko Izumi Nichiata L, 2013. Prevention of sexually transmitted diseases by homosexual and bisexual women: a descriptive study. Online Braz. J. Nurs 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gowen LK, Winges-Yanez N, 2014. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning youths’ perspectives of inclusive school-based sexuality education. J. Sex Res. 51 (7), 788–800. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2013.806648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart SL, Bowen DJ, 2009. Sexual orientation and intentions to obtain breast cancer screening. J. Womens Health (Larchmt) 18, 177–185. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T, McCabe SE, Wilsnack SC, West BT, Boyd CJ, 2010a. Victimization and substance use disorders in a national sample of heterosexual and sexual minority women and men. Addiction 105, 2130–2140. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T, Szalacha LA, McNair R, 2010b. Substance abuse and mental health disparities: comparisons across sexual identity groups in a national sample of young Australian women. Soc. Sci. Med 71, 824–831. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, Szalacha LA, Johnson TP, Kinnison KE, Wilsnack SC, Cho Y, 2010c. Sexual victimization and hazardous drinking among heterosexual and sexual minority women. Addict. Behav 35, 1152–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine, 2011. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington D.C... [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Organization of American States, 2015. Violence Against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Persons in the Americas..

- International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, 2017a. Sexual Orientation Laws in the World: Criminalisation [WWW Document]. URL https://ilga.org/downloads/2017/ILGA_WorldMap_ENGLISH_Criminalisation_2017.pdf (accessed 12.29.18)..

- International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, 2017b. Minorities Report 2017: Attitudes to Sexual and Gender Minorities Around the World. Geneva, Switzerland.. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce B, Brown-Schott N, Hicks V, Johnson RG, Harmon M, Pilling L, 2017. The global health nursing imperative: using competency-based analysis to strengthen accountability for population focused practice, education, and research. Ann. Glob. Heal 83, 641–653. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise SL, Hyde JS, 2012. Victimization experiences of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: a meta-analysis. J. Sex Res. 49, 142–167. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.637247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerker BD, Mostashari F, Thorpe L, 2006. Health care access and utilization among women who have sex with women: sexual behavior and identity. J. Urban Health 83, 970–979. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9096-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr D, Ding K, Burke A, Ott-Walter K, 2015. An Alcohol, Tobacco, and other drug use comparison of lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual undergraduate women. Subst. Use Misuse 50, 340–349. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.980954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsky S, Stall R, Hawk M, Markovic N, 2016. Risk of the metabolic syndrome in sexual minority women: results from the ESTHER Study. J. Womens Heal 25, 784–790. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2015.5496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Sucato G, Stepp SD, Hipwell A, Smith HA, Friedman MS, Chung T, Markovic N, 2012. Substance use and mental health disparities among sexual minority girls: results from the Pittsburgh girls study. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol 25, 15–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Matthews AK, Lee JGL, West BT, Boyd CJ, Arslanian-Engoren C, 2017. Sexual orientation discrimination and tobacco use disparities in the United States. Nicotine Tob. Res 00, 1–9. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meads C, Buckley E, Sanderson P, 2007. Ten years of lesbian health survey research in the UK West Midlands. BMC Public Health 7, 251. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertehikian YA, 2017. Debate about mental and (non) reproductive health: Notes based on lesbian and bisexual women’s experiences in the city of Buenos Aires. La manzana la discordia 12, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, 2003. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull 129, 674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro S, Cecchetto F, Vargas E, Mora C, 2010. Sexual diversity and vulnerability to AIDS: the role of sexual identity and gender in the perception of risk by young people (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 7, 270–282. doi: 10.1007/s13178-010-0030-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mor Z, Eick U, Wagner Kolasko G, Zviely-Efrat I, Makadon H, Davidovitch N, 2015. Health status, behavior, and care of lesbian and bisexual women in Israel. J. Sex. Med 12, 1249–1256. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora C, Monteiro S, 2010. Vulnerability to STIs/HIV: sociability and the life trajectories of young women who have sex with women in Rio de Janeiro. Cult. Heal. Sex 12, 115–124. doi: 10.1080/13691050903180471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscheta MS, Souza LV, Santos MA, 2016. Health care provision in Brazil: a dialogue between health professionals and lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender service users. J. Health Psychol. 21, 369–378. doi: 10.1177/1359105316628749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller A, Hughes TL, 2016. Making the invisible visible: a systematic review of sexual minority women’s health in Southern Africa. BMC Public Health 16 (307) doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2980-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academy of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2015. Strengthening the Scientific Foundation for Policymaking to Meet the Challenges of Aging in Latin America and the Caribbean: Summary of a Workshop. Washington: DC.. doi: 10.17226/21800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Council to Prevent Discrimination, 2010. National Survey on Discrimination in Mexico. Del Miguel Hidalgo.. [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health, 2015. NIH FY 2016–2020 Strategic Plan to Advance Research on the Health and Well-being of Sexual and Gender Minorities. Bethesda, MD.. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2018. Healthy People 2020: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Health [WWW Document]. URL https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-health (accessed 1.28.18).

- Ortiz-Hernández L, 2005. Influencia de la opresion internalizada sobre la salud mental de bisexuales, lesbianas y homosexuales de la Ciudad de Mexico. Salud Ment. Mex. (Mex) 28, 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Hernández L, García Torres MI, 2005. Effects of violence and discrimination on the mental health of bisexuals, lesbians, and gays in Mexico city. Cad. saude publica / Minist. da Saude, Fund. Oswaldo Cruz, Esc. Nac. Saude Publica 21, 913–925. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2005000300026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Hernández L, Granados-Cosme JA, 2006. Violence against bisexuals, gays and lesbians in Mexico city. J. Homosex 50, 113–140. doi: 10.1300/J082v50n04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Hernández L, Gómez Tello BL, Valdés J, 2009. The association of sexual orientation with self-rated health, and cigarette and alcohol use in Mexican adolescents and youths. Soc. Sci. Med 69, 85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization, 2016. PAHO/WHO Urges Transformation of Nursing Education in the Americas [WWW Document]. URL https://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=12003:pahowho-urges-transformation-of-nursing-education-in-the-americas&Itemid=135&lang=fr (Accessed 9.26.18).

- Pinto VM, Tancredi MV, Tancredi Neto A, Buchalla CM, 2005. Sexually transmitted disease/HIV risk behaviour among women who have sex with women. AIDS 19 Suppl 4, S64–9 https://doi.org/00002030-200510004-00011[pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plöderl M, Tremblay P, 2015. Mental health of sexual minorities: a systematic review. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 27, 367–385. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1083949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi RI, Zha P, Kim S, Hindin P, Naqvi Z, Holly C, Dubbs W, Ritch W, 2018. Health care needs and care utilization among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations in New Jersey. J. Homosex 65, 167–180. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1311555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambarran N, Simpson J, 2016. An exploration of the health care experiences encountered by lesbian and sexual minority women in Guyana. Int. J. Sex. Heal 28, 332–342. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2016.1223254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Semlyen J, King M, Varney J, Hagger-Johnson G, 2016. Sexual orientation and symptoms of common mental disorder or low wellbeing: combined meta-analysis of 12 UK population health surveys. BMC Psychiatry 16, 67. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0767-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberman P, Buedo PE, Burgos L, 2016. Barriers to sexual health care in Argentina: perception of women who have sex with women. Rev. Salud Pública 18, 1–12. doi: 10.15446/rsap.v18n1.48047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South China Morning Post, 2018. Gay People Beaten and Raped to ‘cure’ Them of Homosexuality in Ecuador’s ‘rehab Clinics’ [WWW Document]. URL https://www.scmp.com/news/world/americas/article/2132635/gays-ecuador-raped-and-beaten-rehab-clinics-cure-them (Accessed 9.12.18)..

- Steele LS, Ross LE, Dobinson C, Veldhuizen S, Tinmouth JM, 2009. Women’s sexual orientation and health: results from a Canadian population-based survey. Women Health 49, 353–367. doi: 10.1080/03630240903238685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalacha LA, Hughes TL, McNair R, Loxton D, 2017. Mental health, sexual identity, and interpersonal violence: findings from the Australian Longitudinal Women’s Health Study. BMC Womens Health 17, 94. doi: 10.1186/s12905-017-0452-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tat SA, Marrazzo JM, Graham SM, 2015. Women who have sex with women living in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review of sexual health and risk behaviors. J. LGBT Health Res 2, 91–104. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank, 2017. World Bank and Salzburg Global LGBT Forum Call for Inclusion and Equality for Families and Their LGBTI Children [WWW Document]. URL http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2017/06/22/world-bank-and-salzburg-global-lgbt-forum-call-for-inclusion-and-equality (Accessed 9.25.18). .

- The World Bank, 2018. The World Bank in Latin America and the Caribbean [WWW Document]. URL https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/lac (Accessed 8.13.18)..

- Tomicic A, Gálvez C, Quiroz C, Martínez C, Fontbona J, Rodríguez J, Aguayo F, Rosenbaum C, Leyton F, Lagazzi I, 2016. Suicide in lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans populations: Systematic review of a decade of research (2004–2014). Rev. Med. Chil 144, 723–733. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872016000600006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Træen B, Martinussen M, Vitters J, Saini S, 2009. Sexual orientation and quality of life among university students from Cuba, Norway, India, and South Africa. J. Homosex 56, 655–669. doi: 10.1080/00918360903005311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Program, 2017. From Commitment to Action: Policies to End Violence Against Women in Latin America and the Caribbean Regional Analysis Document. Panama City, Panama. [Google Scholar]

- Villar F, Serrat R, de Sao José JM, Montero M, Giuliani MF, Carbajal M, da Cassia Oliveira R, Estrella RN, Curcio C-L, Alfonso A, Tirro V, 2018. Disclosing lesbian and gay male sexual orientation in later life: attitudes of younger and older generations in eight Latin American countries. J. Homosex 8369, 1–24. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2018.1503462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Norris JL, Liu Y, Vermund SH, Qian H-Z, Han L, Wang N, 2012. Risk behaviors for reproductive tract infection in women who have sex with women in Beijing, China. PLoS One 7, e40114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widmer M, Pavesi I, 2016. A gendered analysis of violent deaths. Geneva, Switzerland.. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson L, Harper DC, Tami-Maury I, Zarate R, Salas S, Farley J, Warren N, Mendes I, Ventura C, 2012. Global health competencies for nurses in the Americas. J. Prof. Nurs 28, 213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson L, Moran L, Zarate R, Warren N, Aparecida C, Ventura A, Tamí-Maury I, Amélia I, Mendes C, 2016. Qualitative description of global health nursing competencies by nursing faculty in Africa and the Americas. Rev. Latino-Am. Enferm 24. doi: 10.1590/1518-8345.0772.2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2013. Improving the Health and Well-being of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Persons Report by the Secretariat..

- World Health Organization, 2014. Sexual and Reproductive Health: Sexual Health Issues [WWW Document]. URL https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/sexual_health/issues/en/ (Accessed 12.28.18)..

- Ybarra ML, Rosario M, Saewyc E, Goodenow C, 2016. Sexual behaviors and partner characteristics by sexual identity among adolescent girls. J. Adolesc. Heal 58, 310–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]