Abstract

Objectives:

After the publication of large clinical trials, in January 2014 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended annual lung cancer screening with low-dose CT in a well-defined group of high-risk smokers. A significant proportion of patients with laryngeal cancer (LC) meet the introduced criteria, and we hypothesized that clinical practice would change as a result of these evidence-based guidelines.

Methods:

Retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with LC and treated at Johns Hopkins Hospital who met USPSTF criteria for annual chest screening and were followed for at least 3 consecutive years in the years surrounding the introduction of screening guidelines (January 2010 to December 2017) was performed to identify those who had recommended screening CT chest.

Results:

A total of 151 patients met the inclusion criteria of the study and were followed for a total of 746 patient-years. 184/332 (55%) patient-years in the pre-guidelines period and 246/414 (59%) in the post-guidelines period included at least one recommended chest imaging (CT or PET-CT; p=0.27). 248/332 (75%) patient-years in the pre-guidelines period and 314/414 (76%) in the post-guidelines period included any radiological chest imaging (X-ray, CT or PET-CT; p=0.72). Screening scans were ordered by OHNS (45%), Medical Oncology (31%), Radiation Oncology (8%), and primary care (14%) with 70% of patients missing at least one year of indicated screening.

Conclusions:

The implementation of new lung cancer screening guidelines did not change clinical practice in the management of patients with LC and many patients do not receive recommended screening. Further study concerning potential barriers to effective evidence-based screening and coordination of care is warranted.

Keywords: lung cancer screening, laryngeal cancer, head and neck cancer, lung cancer, CT

Introduction

Worldwide, head and neck cancer (HNC) accounts for more than 550,000 cases and 380,000 deaths annually and its incidence is expected to rise in the future [1,2]. Even though the incidence of HPV-related HNSCC has been steadily rising over last decade, smoking and alcohol consumption remain major risk factors [3]. Smoking as a causative agent of head and neck cancer is even more pronounced in laryngeal cancer, as the majority of diagnosed laryngeal cancers are HPV-negative [4,5].

Smoking is a risk factor not only for head and neck cancer, but also for lung cancer, which has an incidence greater than HNC in smokers and is one of the leading smoking-related cause of death [6,7]. These factors have led to intensive investigation of the role of screening for primary lung cancer, facilitated by the technological development of widespread CT scanners. After the publication of large clinical trials, in January 2014 the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended annual lung cancer screening with low-dose CT in a well-defined group of high-risk smokers [8]. The formal criteria for screening are: adults aged 55–80, with at least 30 pack-years smoking history in those who currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years. These screening programs have been shown to prevent a substantial number of lung cancer–related deaths in patients who were screened with three CT scans over the course of two years [9].

There is significant overlap between the at-risk population for laryngeal cancer and lung cancer given the risk factors for these respective diseases. Smokers make up at least 85% of patients with laryngeal cancer [10], with an average age of 65 [11], demographic factors clearly in line with the screening criteria for primary lung cancer. Further evidence for the overlap between these populations is the fact that the 5-year survival rate for laryngeal cancer is only 63% [12], in part because the incidence of secondary primary lung cancer (SPLC) in this group is high, ranging from 5 to 19%, which in turn has a significant impact on overall survival [13–16].

Physicians who treat patients with laryngeal cancer are therefore encountering a highly-selected group of patients with risk factors for primary or secondary lung cancer, and a significant proportion of patients with laryngeal cancer (LC) meet the formal screening criteria for annual lung CT scans. We hypothesized that clinical practice regarding ordering of chest CTs would change as a result of the introduction of these evidence-based guidelines. We further sought to identify the factors that led to patients receiving or missing the recommended screening and the practice patterns that facilitate the implementation of these guidelines.

Materials and Methods

Ethics

The study was approved by the institutional review board of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA. Informed consent was not required for this retrospective chart review.

Chart Review

We conducted a retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with LC and treated at Johns Hopkins Hospital who met USPSTF criteria for annual chest screening and were followed for at least 3 consecutive years in the years surrounding the January 2014 publication and introduction of screening guidelines (January 2010 to December 2017).

Eligible patients therefore met the following criteria: 1) age of 55 to 77 at the time of the first recorded follow- up year, 2) greater than 30 declared pack-years of smoking history, while a current smoker or having quit within the past 15 years, 3) consistent follow-up of at least 3 consecutive years in our medical records system, and 4) not having synchronous or metastatic lung cancer at presentation, or any other severe lung disease.

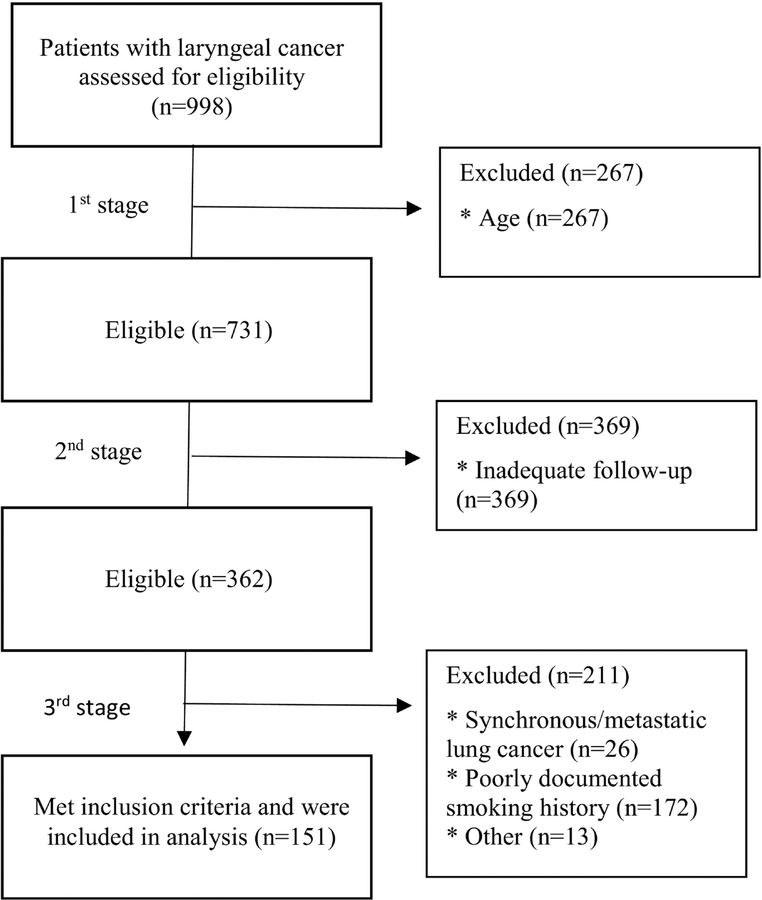

Through a search of billing records, 998 individuals with diagnosed laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma were identified during the included time period. To identify eligible patients for our study, we performed a 3-stage exclusion process (Figure 1). First, we selected patients meeting the age criterion; second, we excluded patients with follow-up shorter than 3 years; finally, we excluded patients not meeting the smoking history criterion or suffering from synchronous or metastatic lung cancer at initial presentation.

Figure 1:

Three stage exclusion protocol to identify index patients that meet USPSTF criteria for annual chest screening. Patients were excluded in three stages: 1) age, 2) inadequate follow-up, and finally 3) smoking history or synchronous lung cancer. Of 998 initial patients, 151 fully met study criteria and were included for further analysis. * Indicates the reason for exclusion.

For every patient who met all of the inclusion criteria, a review of available medical history was performed. In our institution, the electronic medical record (EMR) used to store patients data and medical history is EPIC® (Verona, Wisconsin, United States). In the EMR, we screened 1) all chest radiological exams, 2) all clinical notes to identify chest images performed and / or documented by outside providers, and 3) an additional EMR feature available in our system of databases of the largest outside imaging providers in Maryland, USA (American Radiology and Advanced Radiology), which provide a database of their imaging linked to the native EMR system. For every chest imaging study found, we recorded its type (X-ray, CT with contrast, CT without contrast, PET-CT), the ordering physician’s medical specialty, and purpose of an order (chest screening vs. evaluation of symptoms/complaints). Demographic and clinical characteristics were also recorded (sex, age, race, smoking pack-years, TNM-staging, tumor site).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 6.0, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). A p-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Following identification and exclusion protocols (Figure 1), 151 of 998 laryngeal cancer patients were included in the study. Demographic features of this population are found in Table 1. The majority of the group were men (75.7%) and included patients with early, locally advanced, and advanced LC, fairly evenly divided between glottic (38.4%) and supraglottic (45.0%) cancer.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and laryngeal cancer staging (N = 151)

| Patients (n) | Percentage1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 114 | 75.5% |

| Female | 37 | 24.5% | |

| Age (yrs) | Mean ± SD | 70 ± 6.9 | |

| Race/ethnicity | White | 100 | 66.2% |

| Black | 44 | 29.1 % | |

| Other | 6 | 4.0% | |

| Smoking history (pack yrs) | 30 – 49 | 91 | 60.3% |

| 50 – 99 | 50 | 33.1% | |

| ≥100 | 10 | 6.6% | |

| T staging (TNM2) | T1 | 42 | 27.8% |

| T2 | 38 | 25.2% | |

| T3 | 38 | 25.2% | |

| T4 | 20 | 13.3% | |

| N staging (TNM2) | N0 | 99 | 65.6% |

| N1 | 8 | 5.3% | |

| N2 | 26 | 17.2% | |

| Tumor location | glottic | 58 | 38.4% |

| supraglottic | 68 | 45.0% | |

| subglottic | 4 | 2.6% |

Totals may not equal 151, as data was not available for all patients

7th Edition of the AJCC TNM Classification (2010)

Chest imaging patterns in laryngeal cancer patients

During the study period, a total of 746 patient-years were analyzed - 332 (44.5%) patient-years in the pre-guidelines period (2010–2013) and 414 (55.5%) in the post-guidelines period (2014–2017). As the USPSTF criteria indicate the need for annual lung cancer screening, we searched for any form of chest imaging for each patient in each patient-year. Giving maximal credit to clinicians for the purposes of this study, as well as the real-world practical consideration of avoiding duplicate chest imaging, we considered every ordered chest imaging as a valid screening, irrespective of the stated purpose of an order. For example, if a CT, PET or X-ray was ordered as a part of preoperative work- up or due to a pulmonary complaint it was counted in our study protocol as a valid chest screening for that calendar year.

In both pre-guidelines and post-guidelines periods the most common lung imaging modality was x-ray, but the rate of x-rays dropped from 1.42 tests/patient-year to 0.85 tests/patient-year between these periods (p = 0.0018). This was mirrored by a significant rise in CT scans, from 0.59 tests/patient-year in the pre-guideline period to 0.77 tests/patient-year in the post-guideline period (p = 0.028). There was no statistically significant difference between number of CT scans ordered with contrast and number of CT scans ordered without contrast (Table 2). Interestingly, the rates of PET scans dropped between pre- and post-guideline periods from 0.45 tests/patient-year to 0.26 tests/patient-year (p < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Total chest imaging between 2010 and 2017 in patients with laryngeal cancer.

| Type of chest imaging | Pre-guidelines period | Post-guidelines period | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of tests [N] | Mean [N]/patient-years | Number of tests [N] | Mean [N]/patient-years | ||

| CT(+)1 | 130 | 0.39 | 217 | 0.52 | 0.0579* |

| CT(−)2 | 65 | 0.20 | 102 | 0.25 | 0.2437* |

| All CT | 195 | 0.59 | 319 | 0.77 | 0.0275* |

| PET | 151 | 0.45 | 106 | 0.26 | <0.0001* |

| X-ray | 473 | 1.42 | 353 | 0.85 | 0.0018* |

Unpaired t test with Welch’s correction

CT with contrast

CT without contrast

Annual chest imaging in laryngeal cancer patients

The USPSTF recommendations are based upon the evidence that annual chest imaging improves the survival of smokers through the early detection of lung cancer. Therefore annual chest imaging, ideally a low-dose non-contrast CT scan as per USPSTF guidelines, is essential in this high-risk group of smokers with laryngeal cancer. Out of 332 analyzed patient-years in the pre-guidelines period, only 184 (55%) included at least one chest CT (CT or PET-CT), and out of 414 patient-years in the post-guidelines period, only 246 (59%) included any CT imaging test (Table 3). There was no statistically significant difference between these groups (p= 0.2726). There was also no statistically significant difference between these groups when we compared numbers of patient-years with any radiological chest imaging (Xray, CT or PET-CT), as 248/332 (75%) patient-years in the pre- guidelines period and 314/414 (76%) in the post-guidelines period included at least one chest imaging (X-ray, CT or PET-CT; p=0.72). There is therefore no evidence that the frequency of chest imaging changed for patients with laryngeal cancer as a results of published screening guidelines for smokers.

Table 3.

Annual chest imaging in patients with laryngeal cancer

| Pre-guidelines | Post-guidelines | P-value | 2010–2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-years | 332 | 414 | 746 | |

| Patient-years with min one chest CT or PET-CT | 184 (55%) | 246 (59%) | 0.2726* | 430 (58%) |

| Patient-years with min one chest X-ray or CT or PET-CT | 248 (75%) | 314 (76%) | 0.7185* | 562 (75%) |

Unpaired t test

Annual CT chest imaging by TNM staging

There were some differences in the incidence of chest imaging when examining patients by TNM staging, but these patterns were stable across the study periods and did not change as a result of the introduction of screening guidelines (Table 4). Patients with early laryngeal cancer (T1–T2) and negative nodal status (N0) had significantly less chest imaging ordered (52% and 58%, respectively) compared to advanced laryngeal cancer (T3–T4) and positive nodal status (71% and 66%, respectively; p-value <0.0001 and 0.0004). However, in all TNM staging categories there was no difference in the rates of imaging between the pre- and post-guidelines study periods (p > 0.05 in all groups).

Table 4.

Annual chest imaging in patients with laryngeal cancer by TNM staging

| TNM-staging | Pre-guidelines (patient-years with CT chest imaging) | Post-guidelines (patient-years with CT chest imaging) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1+T2 | 93/182 (51%) | 113/216 (52%) | 0.9826* |

| T3+T4 | 78/116 (67%) | 110/156 (71%) | 0.5652* |

| N0 | 104/202 (51%) | 156/271 (58%) | 0.1894* |

| N+ | 66/88 (68%) | 63/96 (66%) | 0.1670* |

Unpaired t test

Per patient analysis of indicated screening

For the purposes of cancer screening, perhaps the most relevant data point is that each individual patient in this study, based on their smoking history rather than their history of laryngeal cancer, should have had at least one CT scan performed every year. An analysis of the annual chest screening with CT or CT-PET for each individual patient showed that in both pre- and post-guideline periods 70% of patients missed at least one year of indicated screening (Table 5). In this analysis, the number of years with CT chest exam was divided by the number of follow-up years available, for example a CT chest exam in three of four years of follow-up available for analysis would be a screening rate of 75%. Almost 20% of LC patients received no screening at all, and in both pre- and post-guideline periods approximately 50% of patients had annual CT chest imaging performed in 50% or less of analyzed follow-up years. Only 30% of patients received indicated screening in all follow-up years available for analysis.

Table 5.

Percentage of follow-up years with CT/PET chest imaging in the studied population

| % of FU years with CT/PET chest imaging | 0% | 1–49% | 50% | 51–99% | 100% | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-guidelines | 201 (21%)2 |

15 (16%) |

14 (15%) |

19 (20%) |

28 (30%) |

96 (100%) |

| Post-guidelines | 17 (14%) |

17 (14%) |

23 (20%) |

26 (22%) |

35 (30%) |

118 (100%) |

Number of patients

% of total number of patients

Specialists ordering chest scans in laryngeal cancer patients

The radiology reports or physician notes often included information about ordering physicians and the indications for the performed radiologic test. In total, 90 X-rays and 641 CTs/PETs were ordered for screening purposes (45.8 %), whereas 733 X-rays and 132 CTs/PETs were ordered for evaluation of other symptoms, such as dyspnea or suspicion for pneumonia (54.2 %). The Otolaryngologist - Head and Neck surgeons (OHNS) were the medical specialty that ordered the most chest imaging for screening purposes in both the pre- and post-guidelines periods (Table 6). However, the relative percentage of screening tests ordered by OHNS decreased in the post-guidelines period, as the analysis of trends showed that Medical Oncologists and PCPs ordered significantly more CTs with purpose of screening in the post-guidelines period compared with pre-guidelines period (p=.0025 and p=.0026, respectively). Therefore it appears that the introduction of screening guidelines for smokers did change practice patterns in these specialties.

Table 6.

Chest imaging ordered for screening purposes by ordering physicians specialization

| Chest imaging ordered for screening purposes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray | P-value | CT or PET | P-value | |||

| Pre-guidelines | Post-guidelines | Pre-guidelines | Post-guidelines | |||

| OHNS | 31 (56%) | 20 (44%) | .23561 | 169 (60%) | 162 (45%) | .00021 |

| MedOnc | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 1.0002 | 58 (21%) | 112 (31%) | .00251 |

| RadOnc | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 1.0002 | 29 (10%) | 27 (8%) | .14911 |

| PCP* | 11 (20%) | 22 (49%) | .00221 | 19 (7%) | 51 (14%) | .00261 |

| Other** | 9 (16%) | 1 (2%) | .02122 | 7 (2%) | 7 (2%) | .78692 |

| Total | 55 (100%) | 45 (100%) | - | 282 (100%) | 359 (100%) | - |

PCP – including internal medicine specialists, emergency medicine

Other: General surgery, information missing

Chi-square test,

Fisher’s exact test

Discussion

Development of lung cancer as a secondary malignancy in laryngeal cancer is one of the strongest factors adversely affecting overall survival. This is juxtaposed against the known clinical fact that early glottic cancer is a highly curable cancer and often does not include neck or chest CT as the part of initial diagnostic work-up [12,14] due to the low rates of cervical or pulmonary spread in early stage disease. However, the vast majority of patients presenting with laryngeal cancer have a significant smoking history regardless of their laryngeal cancer staging, and would be included in the evidence-based guidelines for annual lung CT screening regardless of their laryngeal cancer.

Our findings suggest that in a highly selected group of patients with laryngeal cancer with significant smoking history, who meet all the criteria for annual chest screening, the rate of recommended chest CT has not significantly changed after the introduction of USPSTF guidelines [8]. In both periods (pre- and post-guidelines) only 30% of patients had their CT chest imaging done every year. We suspect that one of the possible causes is that the aforementioned guidelines do not imply who is responsible for implementing screening in group of smokers with head and neck cancer history. It possible that PCPs are reluctant to order screening imaging, as these patients are regularly seen and followed-up by otolaryngologists- head and neck surgeons (OHNS), radiation oncologists, or medical oncologists. On the other hand, cancer specialists and surgeons might feel that implementation of the USPSTF guidelines is best left to the PCPs as part of care coordination, regardless of previous history of malignancy. Why so many patients miss their indicated screening could be the subject of future study, including an analysis of which physician specialty is most viewed by patients as ‘their physician’ for laryngeal cancer care and which is ‘their physician’ for smoking- related lung screening.

Despite the large percentage of patients missing indicated lung cancer screening, one positive trend identified in our study is that the number of X-rays ordered for screening is significantly decreasing. This is concordant with evidence-based medicine, as chest CT was proven superior to X- ray in reducing lung cancer mortality [17,18]. In our sample, the number of ordered PET-CTs also decreased significantly. The number of patient-years of patients with advanced cancer (T3,T4) in both periods was comparable (116 pt-yrs vs. 156 pt-yrs), so the most reasonable explanation is a shift in physician practice in their selection of imaging modality. What we observed in our population is that in the pre-guidelines period many of the patients had as many as 3 or 4 PET-CTs per year, whereas in the post-guidelines period the maximum number of ordered PET-CTs per year was two, which could be a reflection of an evidence-based medicine approach to annual screening.

Our study has limitations, most notably the fact that our conclusions are based on a patient group seen at one academic medical center. Nevertheless, there is no reason to suspect that our center is unique in its lack of responsiveness to the publication of new evidence-based guidelines [19, 20]. The implementation of published guidelines is often significantly delayed, if ever achieved, and multiple specialists following each patient with laryngeal cancer likely further exacerbated the problem, as physicians could reasonably assume someone else was taking care of ordering the screening. We also acknowledge the potential for selection bias as a limitation of our study. Approximately 50% of patients meeting the age criterion were excluded based on the poor quality of follow-up record. The fragmentation of care in the United States and the lack of a unified medical record means that it is possible that patients included in our study had recommended imaging outside our ability to capture in our EMR or physician notes. Finally, another factor limiting our results is unreliable documentation of smoking history. To select patients definitely meeting USPSTF criteria for annual lung screening we were forced to exclude 172 patients based on their declared smoking history who otherwise had appropriate follow-up history and fell within the target age demographic. In majority of cases, pack- years were not recorded in any form in their medical chart. As smoking history is one of the most important criterion in the introduced guidelines, accurate reporting of tobacco exposure in the standardized measure of pack-years should be a necessity in every day practice.

Conclusion

Patients with laryngeal cancer are likely to be smokers who meet the USPSTF guidelines for annual lung CT screening for the early detection of lung cancer. Unfortunately, the implementation of new lung cancer screening guidelines did not change clinical practice in the management of patients with LC and many patients do not receive recommended screening. Further study concerning potential barriers to effective evidence-based screening and coordination of care is warranted.

Financial Support:

Financial Support for this study was provided by the NIDCD Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award 1K23DC014758 (S. Best).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors have any conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

The authors whose names are listed immediately above certify that they have NO affiliations or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Reference

- 1.Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration C, Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, et al. Global, Regional, and National Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life-years for 32 Cancer Groups, 1990 to 2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(4):524–548. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis A, Kang R, Levine A, Maghami E. The New Face of Head and Neck Cancer: The HPV Epidemic. Oncology (Williston Park). 2015;29(9):616–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallo A, Degener AM, Pagliuca G, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus and adenovirus in benign and malignant lesions of the larynx. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141(2):276–281. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumann JL, Cohen S, Evjen AN, et al. Human papillomavirus in early laryngeal carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(8):1531–1537. doi: 10.1002/lary.20509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses--United States, 1997–2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(25):625–628. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15988406. Accessed February 28, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wyss A, Hashibe M, Chuang S-C, et al. Cigarette, cigar, and pipe smoking and the risk of head and neck cancers: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(5):679–690. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Humphrey L, Deffebach M, Pappas M, et al. Screening for Lung Cancer: Systematic Review to Update the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24027793. Accessed February 25, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, Aberle DR, Adams AM, et al. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Low-Dose Computed Tomographic Screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markou K, Christoforidou A, Karasmanis I, et al. Laryngeal cancer: epidemiological data from Northern Greece and review of the literature. Hippokratia. 2013;17(4):313–318. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25031508. Accessed February 28, 2019. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) Research Data (1973–2015), National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, released April 2018, based on the November 2017 submission. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dikshit RP, Boffetta P, Bouchardy C, et al. Risk factors for the development of second primary tumors among men after laryngeal and hypopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103(11):2326–2333. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sjögren EV, Snijder S, van Beekum J, Baatenburg de Jong RJ. Second malignant neoplasia in early (TIS-T1) glottic carcinoma. Head Neck. 2006;28(6):501–507. doi: 10.1002/hed.20453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farhadieh RD, Salardini A, Yang JL, Russell P, Smee R. Diagnosis of second head and neck tumors in primary laryngeal SCC is an indicator of overall survival and not associated with poorer overall survival: A single centre study in 987 patients. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101(1):72–77. doi: 10.1002/jso.21413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu Y-B, Chang S-Y, Lan M-C, Huang J-L, Tai S-K, Chu P-Y. Second Primary Malignancies in Squamous Cell Carcinomas of the Tongue and Larynx: An Analysis of Incidence, Pattern, and Outcome. J Chinese Med Assoc. 2008;71(2):86–91. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(08)70080-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu C, Liu Z, Zhu F, Li S, Jiang L. A meta-analysis: is low-dose computed tomography a superior method for risky lung cancers screening population? Clin Respir J. 2016;10(3):333–341. doi: 10.1111/crj.12222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, Aberle DR, Adams AM, et al. Reduced Lung- Cancer Mortality with Low-Dose Computed Tomographic Screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.S, Doshi D, Wisnivesky JP, Lin JJ. Attitudes About Lung Cancer Screening: Primary Care Providers Versus Specialists. Clin Lung Cancer. 2017;18(6):e417–e423. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2017.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ersek JL, Eberth JM, McDonnell KK, et al. Knowledge of, attitudes toward, and use of low- dose computed tomography for lung cancer screening among family physicians. Cancer. 2016;122(15):2324–2331. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]