Abstract

Synthetic CRISPR-Cas transcription factors enable the construction of complex gene expression programs, and chemically-inducible systems allow precise control over the expression dynamics. To provide additional modes of regulatory control, we have constructed a chemically-inducible CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) system in yeast that is mediated by recruitment to MS2-functionalized guide RNAs. We use reporter gene assays to systematically map the dose dependence, time-dependence, and reversibility of the system. Because the recruitment function is encoded at the level of the guide RNA, it is straightforward to target multiple genes and independently regulate expression dynamics at individual targets. This approach provides a new method to engineer sophisticated, multi-gene programs with precise control over the dynamics of gene expression.

Keywords: Gene expression, Synthetic biology, CRISPR-Cas, Protein-protein interactions, RNA

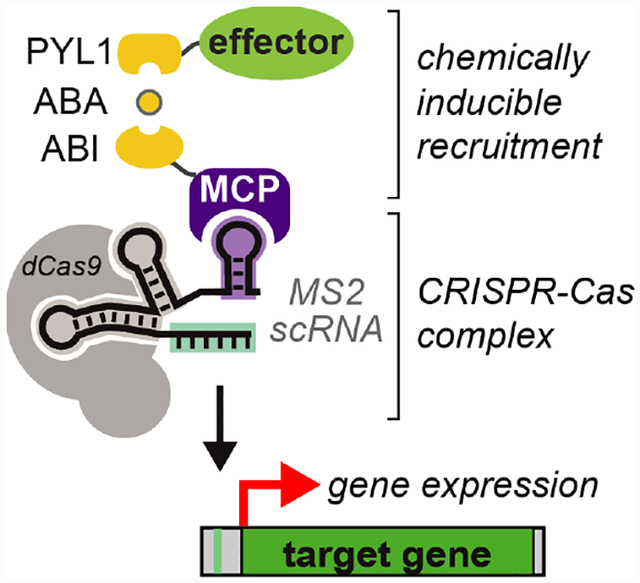

Graphical Abstract

Chemically-inducible recruitment to the CRISPR-Cas complex enables control of transcriptional dynamics. Recruitment is mediated by chemical dimerization domains that link effector proteins to an RNA binding domain. Each guide RNA encodes the gene target and the effector protein to be recruited, which enables independent control of gene expression timing at distinct gene targets.

Biological systems control the expression of many different genes simultaneously, and the timing and amplitude of gene expression is often subject to precise regulatory control. Recent advances in biological and chemical tools have enabled the construction of synthetic systems that can mimic key features of these endogenous biological systems. For example, the CRISPR-Cas system allows programmable control at multiple gene targets, using a catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9), a single guide RNA (sgRNA) to target DNA, and an associated effector protein to regulate transcription.[1] Further, chemically-inducible systems that control the assembly, stability, or activity of the CRISPR-Cas complex can be used to regulate the timing of gene expression.[2–11]

We have constructed a straightforward method to target multiple genes and independently regulate expression dynamics at distinct targets. We use modified sgRNAs, termed scaffold RNAs (scRNAs), that are extended with hairpin sequences to recruit RNA binding proteins which are in turn fused to a chemically-inducible transcriptional effector.[12] By encoding both the gene target and the identity of the effector protein to be recruited, these scRNAs allow different gene targets to be regulated by different effector proteins. Here we demonstrate that recruitment of a transcriptional activator to the scRNA can be mediated by the abscisic acid (ABA)-inducible ABIPYL1 interaction,[13] which has previously been used to recruit effectors directly to dCas9 fusion proteins.[2] Using this system, we show independent regulation of two genes in yeast, one with an ABA-dependent scRNA for CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) with dynamic control and one with an ABA-independent sgRNA that mediates CRISPRi-based repression. Analogous systems have been engineered with orthogonal dCas9 or TALE proteins;[2–4] our system achieves a similar function with a single dCas9 and orthogonality encoded at the RNA level.

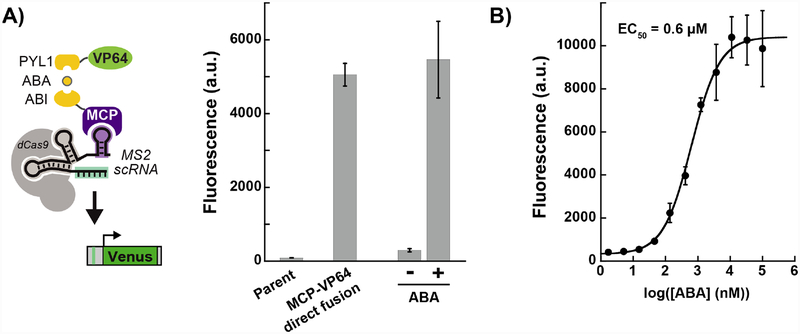

To construct a chemically-inducible CRISPRa system in which recruitment is mediated by interactions with the guide RNA, we engineered two effector protein fusions: MCP-ABI and PYL1-VP64. The RNA binding protein MCP interacts with the MS2 hairpins presented on the scRNA and VP64 serves as the transcriptional activator. Addition of ABA recruits PYL1-VP64 to MCP-ABI (Figure 1A). Recruitment of VP64 to a CRISPR-Cas complex targeted upstream of a Venus fluorescent reporter gene should result in transcriptional activation.[12] When the MCP-ABI and PYL1-VP64 constructs were delivered to a reporter yeast strain with dCas9 and an MS2 scRNA, we observed ABA-dependent Venus reporter expression, comparable to that observed when MCP and VP64 are fused directly (Figure 1A). In the absence of ABA, Venus expression is low, although it is detectable above the background fluorescence in the parent yeast strain, suggesting that there may be some modest ABA-independent recruitment of VP64. By varying the concentration of ABA, we observed dose-dependent reporter gene expression with an EC50 of 0.6 μM (Figure 1B), a concentration ~10X lower than EC50 values previously reported with ABA in mammalian cells.[2,13] ABA-mediated gene activation produces a homogenous population-level response in which intermediate ABA levels produce intermediate levels of gene expression (Supporting Figure S1), in contrast to some inducible yeast expression systems that exhibit switch like behavior.[14]

Figure 1.

Chemically-induced recruitment to the CRISPR-Cas complex activates reporter gene expression in yeast. A) ABA-inducible recruitment of VP64 to the CRISPR-Cas complex via the RNA binding protein MCP activates gene expression. Cultures were incubated for 4 hrs with 100 μM ABA. Treatment with DMSO (i.e. -ABA) does not activate gene expression. ABA-induced activation is comparable to that observed with a direct MCP-VP64 fusion protein. B) Dose-response after 5 hr induction with ABA. The parent strain for this experiment was yDCB03, which was transformed with the MS2 scRNA plasmid pJZC588_TET (see Supporting Information). The constitutive MCP-VP64 control strain was generated by transforming the same scRNA into strain yJZC06. Fluorescence levels are given in arbitrary units (a.u.). Values are median ± SD for three measurements.

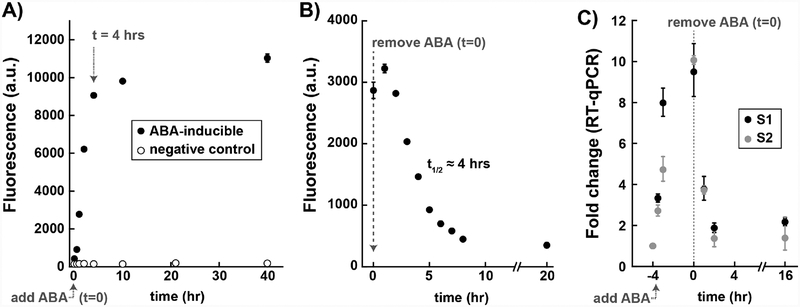

To characterize the dynamics of ABA-induced gene expression, we measured timecourses for reporter gene activation after addition and removal of ABA. After addition of ABA, we observed a steady increase in fluorescent reporter protein level over the first 4 hours before reaching a plateau that remained relatively stable up to at least 40 hours (Figure 2A). After removal of ABA, we observed a decrease in fluorescent reporter protein level with a t1/2 of ~4 hours (Figure 2B). To directly measure mRNA levels, we performed RT-qPCR. After removal of ABA, we observed a 2.5-fold decrease in Venus reporter mRNA at 1 hr, and nearly complete loss at 2 hrs (Figure 2C). This behavior is consistent with typical yeast mRNAs, which degrade with half-times <30 min,[15] and suggests that ABA-mediated transcription stops relatively quickly after removal. Because fluorescent proteins derived from GFP are quite stable,[16] the fluorescent reporter protein persists for several hours after the mRNA has degraded.

Figure 2.

Dynamics of gene activation and inactivation. A) Timecourse for Venus fluorescent reporter protein levels after stimulation with 100 μM ABA. The negative control is a yeast strain with a guide RNA lacking the MS2 hairpin that recruits MCP-ABI. B) Timecourse for Venus fluorescent reporter protein levels after removal of ABA. Cells were incubated with 500 nM ABA for 4 hrs, followed with ABA removal by the dilution of cells into fresh media. Fluorescence levels are given in arbitrary units (a.u.). Values are median ± SD for three measurements (A) or two measurements (B). C) Timecourse for Venus mRNA levels before and after removal of ABA. Cells were incubated with 500 nM ABA for 4 hrs, followed with ABA removal by dilution. Expression levels from RT-qPCR were calculated using the ΔΔCT method[29] from three technical replicates each for the target gene (Venus) and the reference gene (ACT1). Error bars represent standard deviations for ΔΔCT, with the upper bound 2−(ΔΔCt -stdev) and lower bound 2−(ΔΔCt + stdev). S1 and S2 are independent biological replicates. These experiments were performed with strain yDCB03 transformed with the MS2 scRNA plasmid pJZC588_TET. See Figure S2 in Supporting Information for additional washout experiments performed at higher ABA concentrations; at all ABA concentrations we observed similar results using dilution or centrifugation to remove ABA.

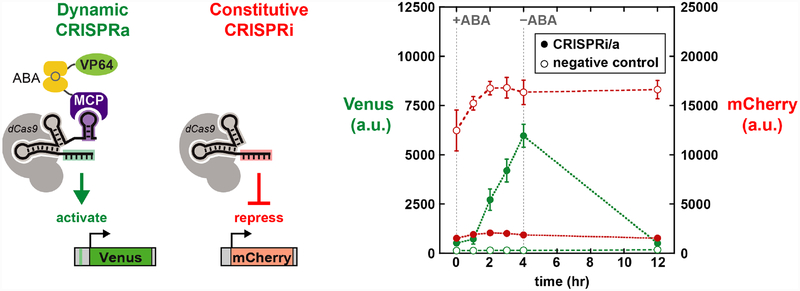

The ability to dynamically regulate gene expression with effector protein recruitment via the guide RNA allows us to encode multi-gene programs in which the timing of gene expression can be independently regulated at each gene target. Because each guide RNA encodes the gene target and the function to be executed at that target, a guide that is regulated by ABA-inducible recruitment will result in distinct gene expression dynamics versus a guide that constitutively regulates its target. To demonstrate this mode of regulation, we used a dual-reporter yeast strain with weak Venus expression and strong mCherry expression. We integrated dCas9, MCP-ABI, and PYL1-VP64 into the yeast genome and delivered two guide RNAs: one MS2 scRNA for ABA-inducible Venus expression and one unmodified sgRNA to repress mCherry by a CRISPRi mechanism. With both guide RNAs expressed, adding and removing ABA produced a dynamic pulse of Venus expression while mCherry remained constitutively repressed (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Independent control of expression dynamics at two genes. The CRISPR-Cas system controls expression of both Venus and mCherry reporter genes. The Venus-targeting MS2 scRNA recruits VP64 in the presence of ABA to activate reporter gene expression. The mCherry-targeting sgRNA constitutively represses its gene target by a CRISPRi-mechanism. Cells were induced with 500 nM ABA for 4 hrs, followed with ABA removal by the dilution of cells into fresh media. Closed symbols (●) are for cells expressing both a Venus-targeting MS2 scRNA and an mCherryrepressing sgRNA. Open symbols (○) are for negative control cells with a Venus-targeting guide RNA lacking the MS2 hairpin. Green symbols are Venus fluorescence levels and red symbols are mCherry fluorescence levels. See Figure S3 in Supporting Information for controls with each individual guide RNA expressed separately. The parent strain for this experiment was yDCB24 (see Supporting Information). Fluorescence levels are given in arbitrary units (a.u.). Values are median ± SD for three measurements.

Using chemically-inducible synthetic transcription factors to regulate the amplitude and timing of gene expression has powerful applications for both studying and engineering the transcriptome.[17] Our method uses the ABA system for chemically-induced dimerization together with RNA binding proteins to mediate recruitment of effector proteins to the CRISPR-Cas complex. This approach is complementary to recent work demonstrating that RNA-mediated recruitment to the CRISPR-Cas complex can be chemically controlled with other small molecule regulators: either rapamycin for recruitment or trimethoprim for a degradation-domain strategy.[6,9] As we have demonstrated here, RNA-mediated recruitment strategies allow straightforward implementation of transcriptional programs where distinct gene targets are regulated independently. Conceptually similar approaches have been demonstrated using orthogonal dCas9 or TALE proteins in mammalian cells.[2–4] While our system was prototyped in yeast, it should be straightforward to implement in mammalian cells, as all of the component parts have been used in mammalian systems.[2,12] Further, we envision direct applications in yeast for dynamic control of gene expression programs in both research and biotechnology applications.[18]

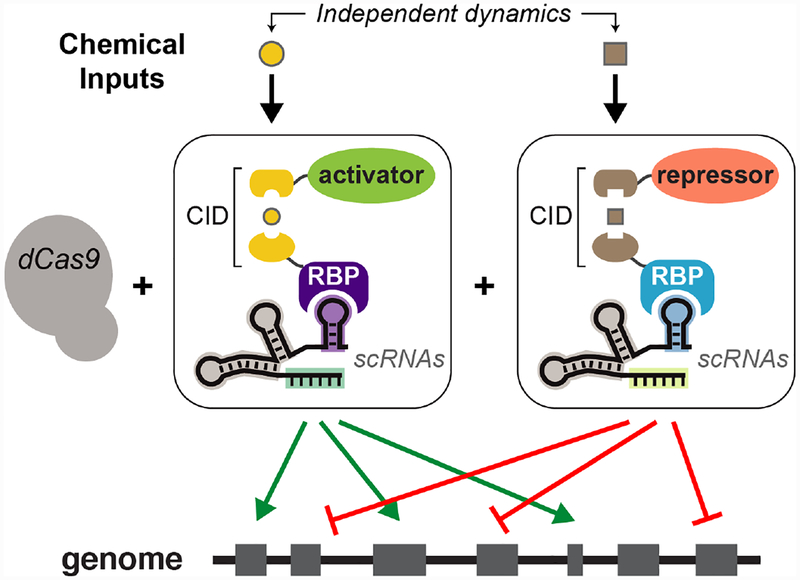

The system we demonstrate here uses a single chemically-inducible recruitment module, so that only one set of gene targets is dynamically regulated while another set can be constitutively controlled. A potential advantage of scRNA-based recruitment is that many different RNA-protein interactions have been used successfully with the CRISPR-Cas system;[12,19–22] pairing distinct RNA-protein interactions with orthogonal chemically-induced recruitment systems[23] could dramatically expand the scope and capabilities of CRISPR-Cas-mediated transcriptional regulatory networks (Figure 4). To achieve such a system, future experiments will test additional chemical recruitment modules with the CRISPR-Cas system in yeast. These modules could be paired with the VP64 activator to independently control gene activation dynamics for two sets of genes. Alternatively, introducing additional types of effectors, such as the repressor MxiI,[24,25] could enable independent dynamic control of both activation and repression.

Figure 4.

Orthogonal chemically-induced dimerization (CID) modules will enable the construction of complex, multi-gene expression programs where different sets of genes can be dynamically regulated independently.

Experimental Section

Materials.

The ABI and PYL1 fragments used to construct MCP-ABI and PYL1-VP64 expression plasmids were a gift from Stanley Qi (Addgene plasmid #84239).[2] Complete sequences of these constructs are included in the Supporting Information. The plasmid used to express two guide RNAs for simultaneous targeting of the Venus and mCherry reporter genes was constructed as described.[26] All other plasmids used in this work were described previously.[12]

Yeast strain construction and analysis.

Yeast (S. cerevisiae) transformations were performed using the standard lithium acetate method.[27] The parent yeast strain for all experiments was SO992 (W303; MATa ura3 leu2 trp1 his3). The Venus reporter strains were generated from yJZC02,[12] which contains a genomically-integrated Tet-On Venus reporter. Complete descriptions of plasmids and yeast strains are provided in the Supporting Information.

After transformations of chemically inducible CRISPR components, yeast strains were grown overnight at 30 °C in the appropriate media (SD Complete or SD -Ura). For time dependent activation experiments, overnight cultures were diluted 1:50 in media containing 100 μM ABA (Sigma-Aldrich, #A1049) and grown for the stated time points. For dose-dependence experiments, overnight cultures were diluted 1:50 in media containing the stated concentration of ABA and grown for 5 hours at 30 °C. 50 μg/mL cycloheximide was then added to halt protein translation,[28] and cells were analyzed by flow cytometry as described below.

For time dependent ABA washout experiments, overnight cultures were diluted 1:50 into media containing ABA and grown for 4 hours. Cultures were subsequently diluted in SD Complete media to a final concentration of ≤5 nM ABA and shaken at 30 °C. At each timepoint, yeast protein translation was stopped with 50 μg/mL cycloheximide and then pelleted by centrifugation, aspirated, and re-suspended in 500 μL SD Complete media containing 50 μg/mL cycloheximide. For the timecourses in Figure 2B&C, an ABA concentration of 500 nM (close to the observed EC50) was chosen for these experiments so that a 1:100 dilution would be sufficient to wash out ABA. It was possible to wash out ABA concentrations up to at least 10 μM using this method (Supporting Figure S2). As an alternative to dilution, ABA can be washed out by centrifuging the cells, discarding the supernatant, washing once with SD Complete media without ABA, centrifuging again and resuspending in SD Complete (Figure S2).

Yeast cell fluorescence was analyzed by flow cytometry using a BD LSRII instrument. We gated for single cells using the SSC-A vs. FSC-A plot. When analyzing fluorescence histograms, in some cases there was a small population of non-fluorescent cells (typically 5–15% of the population) that resulted in a bimodal distribution of fluorescence values (Supporting Figure S1). This population was observed in constitutively active and ABA-induced samples and most likely results from a population of dead or quiescent cells. In these cases, we excluded the non-fluorescent population to accurately report the median fluorescence value for the responsive population.

RT-qPCR.

For RT-qPCR experiments, cells were incubated with 500 nM ABA for four hours. ABA was then removed by dilution into fresh media as described above. At the indicated timepoints before and after ABA removal, cells (~3.5 OD∙mL) were pelleted by centrifugation, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. Total RNA was extracted using an Aurum Total RNA Mini Kit (Bio-Rad) after treatment with zymolyase (Zymo Research). 0.5 μg of RNA was converted to cDNA using iScript reverse transcriptase (Bio-Rad) in 20 μL reactions. qPCR was performed using SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) with a 56 °C annealing temperature and 10 μL reaction volumes. qPCR reactions were performed in triplicate on a CFX Connect (Bio-Rad) using 0.25 ng of cDNA, 250 nM primer concentration, and 15 s extension time. ACT1 was used as a reference gene for normalization. Control samples without reverse transcriptase were analyzed to confirm the absence of gDNA contamination. Primer sequences are listed in the Supporting Information. Expression levels for the Venus reporter gene were calculated relative to ACT1 using the ΔΔCT method.[29]

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Career Award at the Scientific Interface from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (J.G.Z.) and NIH R35 GM124773 (J.G.Z.). We thank members of the Zalatan lab for helpful comments and suggestions.

References

- [1].Xu X, Qi LS, J. Mol. Biol 2019, 431, 34–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gao Y, Xiong X, Wong S, Charles EJ, Lim WA, Qi LS, Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 1043–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bao Z, Jain S, Jaroenpuntaruk V, Zhao H, ACS Synth. Biol 2017, 6, 686–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Nomura W, Matsumoto D, Sugii T, Kobayakawa T, Tamamura H, Biochemistry 2018, 57, 6452–6459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zetsche B, Volz SE, Zhang F, Nat. Biotechnol 2015, 33, 139–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Braun SMG, Kirkland JG, Chory EJ, Husmann D, Calarco JP, Crabtree GR, Nat. Commun 2017, 8, 560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chen T, Gao D, Zhang R, Zeng G, Yan H, Lim E, Liang F-S, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 11337–11340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Khakhar A, Bolten NJ, Nemhauser J, Klavins E, ACS Synth. Biol 2016, 5, 279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Maji B, Moore CL, Zetsche B, Volz SE, Zhang F, Shoulders MD, Choudhary A, Nat. Chem. Biol 2017, 13, 9–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Shrimp JH, Grose C, Widmeyer SRT, Thorpe AL, Jadhav A, Meier JL, ACS Chem Biol 2018, 13, 455–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gangopadhyay SA, Cox KJ, Manna D, Lim D, Maji B, Zhou Q, Choudhary A, Biochemistry 2019, 58, 234–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zalatan JG, Lee ME, Almeida R, Gilbert LA, Whitehead EH, La Russa M, Tsai JC, Weissman JS, Dueber JE, Qi LS, Lim WA, Cell 2015, 160, 339–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Liang F-S, Ho WQ, Crabtree GR, Sci. Signaling 2011, 4, rs2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hawkins KM, Smolke CD, J. Biol. Chem 2006, 281, 13485–13492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wang Y, Liu CL, Storey JD, Tibshirani RJ, Herschlag D, Brown PO, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 5860–5865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Li X, Zhao X, Fang Y, Jiang X, Duong T, Fan C, Huang CC, Kain SR, J. Biol. Chem 1998, 273, 34970–34975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Jusiak B, Cleto S, Perez-Pinera P, Lu TK, Trends Biotechnol 2016, 34, 535–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Nielsen J, Keasling JD, Cell 2016, 164, 1185–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mali P, Aach J, Stranges PB, Esvelt KM, Moosburner M, Kosuri S, Yang L, Church GM, Nat. Biotechnol 2013, 31, 833–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Konermann S, Brigham MD, Trevino AE, Joung J, Abudayyeh OO, Barcena C, Hsu PD, Habib N, Gootenberg JS, Nishimasu H, Nureki O, Zhang F, Nature 2015, 517, 583–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Shechner DM, Hacisuleyman E, Younger ST, Rinn JL, Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 664–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Cheng AW, Jillette N, Lee P, Plaskon D, Fujiwara Y, Wang W, Taghbalout A, Wang H, Cell Res 2016, 26, 254–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Fegan A, White B, Carlson JCT, Wagner CR, Chem. Rev 2010, 110, 3315–3336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gilbert LA, Larson MH, Morsut L, Liu Z, Brar GA, Torres SE, Stern-Ginossar N, Brandman O, Whitehead EH, Doudna JA, Lim WA, Weissman JS, Qi LS, Cell 2013, 154, 442–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gander MW, Vrana JD, Voje WE, Carothers JM, Klavins E, Nat. Commun 2017, 8, 15459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zalatan JG, Methods Mol. Biol 2017, 1632, 341–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gietz RD, Schiestl RH, Nat. Protoc 2007, 2, 31–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Belle A, Tanay A, Bitincka L, Shamir R, O’Shea EK, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 13004–13009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD, Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.