Abstract

Fruits are major sources of essential nutrients and serve as staple foods in some areas of the world. The increasing human population and changes in climate experienced worldwide make it urgent to the production of fruit crops with high yield and enhanced adaptation to the environment, for which conventional breeding is unlikely to meet the demand. Fortunately, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) technology paves the way toward a new horizon for fruit crop improvement and consequently revolutionizes plant breeding. In this review, the mechanism and optimization of the CRISPR system and its application to fruit crops, including resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses, fruit quality improvement, and domestication are highlighted. Controversies and future perspectives are discussed as well.

Subject terms: Genetic engineering, Molecular engineering in plants

Introduction

Fruits are major sources of fibers, vitamins, and minerals worldwide1. In some parts of Asia, Africa, and South America, banana, breadfruit, and date fruit also serve as staple foods2–4. Fruit crops are at high risk under climate change5. To increase the chances of a steady fruit supply, our ancestors domesticated wild plant species into cultivated crops. Following the “rediscovery” of Mendel’s laws in 1900, breeders started selecting and crossing superior plants6. However, conventional breeding has major shortcomings. First, it largely depends on existing natural allelic variations and is thus inefficient for obtaining the desired characteristics by random mixing of tens of thousands of genes5. Although conventional breeding has increased crop productivity, it is often accompanied by loss of fitness and genetic diversity7, and it is a rather time-consuming practice that could hardly ensure a sufficient food supply for the rapidly growing human population around the world8. Therefore, continuous technological innovation is required to meet the increasing demands of consumers9.

Genetic engineering techniques have numerous applications in fruit crops, as they allow improvement of important agronomic traits such as biotic and abiotic stress tolerance and fruit quality. During the past two decades, several fruit crops have been modified using these techniques. In contrast to conventional breeding, recombinant DNA technology allows transfer of the desired genes from any organism, plant or microorganism into fruit crops, extending the opportunities for fruit yield enhancement by offering new genotypes and phenotypes for breeding purposes, and ultimately improving fruit quality as well as enhancing shelf life. Thus, genetic engineering has been ranked as the fastest developing technology in agriculture10. The organisms obtained by recombinant DNA technology are termed “genetically modified” (GM). In 1994, the transgenic “Flavr Savr tomato” was approved for commercial growth in the United States (US) by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The modification it contained allowed a slowing of its ripening process and prevented it from softening after picking. The GM papaya authorized for marketing can resist ring spot virus attacks and show enhanced productivity. Eighty percent of Hawaiian papaya produced today is genetically engineered, and no alternative method is available11.

However, the development of new GM crops is largely affected by regulatory-approval processes because the purpose of the approval system is preventing harm to human health and the environment, as well as avoiding economic losses12. These regulations also help ensure consumer confidence in GM crop biosafety13. As a result, the costs of obtaining approval for new GM crops can be very high, and the regulatory requirements may also delay product marketing14. Jefferson et al.15 have argued that these stringent regulations can result in unnecessary barriers to the introduction of new GM crops. Thus, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) technology may be a better choice: in 2016, a CRISPR-edited mushroom escaped US regulation as it fell outside the GM organisms legislation by not containing foreign DNA16. In 2017, the FDA approved the marketing of a false flax with increased oil content and a drought-tolerant soybean17, indicating that the CRISPR-edited crops were not under the same stringent regulations as traditional GM crops and that the CRISPR technology would definitely revolutionize the pace of crop breeding18.

Genome editing has been revolutionized by the development of CRISPR technology

The discovery of CRISPR in the prokaryote immune system

The CRISPR system is a sophisticated adaptive immune mechanism present in bacteria and Archaea for defense against invading bacteriophages and exogenous plasmids19. It was first discovered in the genome of Escherichia coli in 198720 and officially named by the Dutch scientist who identified CRISPR-associated (Cas) genes21. In 2005, three different research groups simultaneously found that the short sequences of many CRISPR spacers were highly homologous with sequences originating from extra chromosomal DNA22–24, indicating a relationship between CRISPR and specific immunity. Nearly a decade later, CRISPR-Cas was successfully engineered into an efficient tool to edit human, animal, and plant genomes25,26, extensively boosting its application in fields as diverse as pharmacology, animal domestication, and food science27.

A complete CRISPR-Cas locus comprises a CRISPR array that harbors short repetitive elements intercalated with invader DNA-targeting spacers, an AT-rich leader sequence, and an operon of Cas genes encoding the Cas proteins28. Based on the different participating Cas proteins, CRISPR-Cas systems can be categorized into three main types: type I and type III systems use a large multi-Cas protein complex for binding and targeting29,30, while the type II system requires only a single protein, the CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9), for RNA-guided double-stranded DNA recognition and cleavage using its two distinct domains, RuvC and HNH31. The simplicity of the type II CRISPR (i.e., of the CRISPR-Cas9 system) enabled remarkable progress in genome engineering32.

The mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9

In general, the action of the CRISPR-Cas9 system can be divided into three stages in response to invading foreign DNA33,34: (i) acquisition stage—the invading DNA is identified and a spacer sequence derived from the target DNA is inserted into the host CRISPR array to establish immunological memory; (ii) expression stage—the Cas9 protein is expressed, and the CRISPR array is transcribed into a precursor RNA transcript (pre-crRNA). A non-coding trans-activating CRISPR RNA (crRNA) then hybridizes to the pre-crRNA and Cas9 protein and processes them into mature RNA units known as crRNAs; and (iii) interference stage—the mature crRNA guides the Cas9 protein to recognize the appropriate DNA target, leading to the cleavage and degradation of the invading foreign DNA.

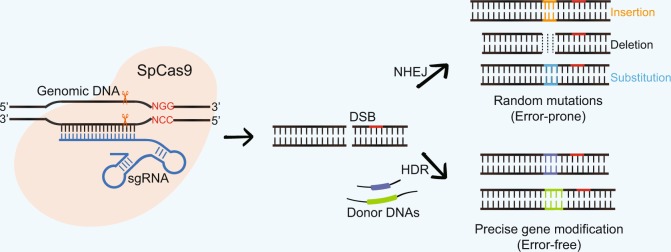

The Cas9 protein cuts the DNA to generate a double-strand break (DSB), triggering cellular DNA repair mechanisms (Fig. 1). In the absence of a homologous repair template, the error-prone non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) pathway is activated and introduces random insertions/deletions or even substitutions at the DSB site, generally resulting in the disruption of gene function. Alternatively, if donor DNA template homologous to the sequence surrounding the DSB site is available, the error-free homology-directed repair (HDR) pathway is initiated, leading to mutations that perform precise gene modification, including gene knock-in, deletion, or mutation35. At present, the most commonly used Cas9 protein comes from Streptococcus pyogenes (Sp)36. To exploit this system for genome editing, synthetic single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) are required to construct the CRISPR-Cas9 expression cassettes. The Cas9 protein is then guided to specific genomic sites by the sgRNAs that recognize the NGG-type protospacer adjacent motif and targets DNA sequences through Watson–Crick base pairing37 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome engineering in plants.

The sgRNA directs the SpCas9 protein to bind genomic DNA through a 20-nucleotide sequence and further guides it to introduce a DSB. This DSB causes random mutations when repaired by the error-prone NHEJ pathway or precise gene modification when repaired by the error-free HDR pathway. CRISPR, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat; Cas, CRISPR-associated; DSB, double-strand break; HDR, homology-directed repair; NHEJ, non-homologous end-joining; sgRNA, single-guide RNA

The optimization of the CRISPR-Cas system in plants

Since the CRISPR-Cas system was successfully engineered to edit plant genomes in 2013, numerous efforts have been made to transform it into a more powerful tool. At present, CRISPR-Cas has multiplex editing capability, that is, it edits more than one gene at a time38. In addition, CRISPR-Cas can target not only the open reading frame (ORF)39 and untranslated region40 of one coding gene but also non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) including long ncRNA41 and microRNA42, as well as promoter regions43. Single-base substitutions at genomic targets without requiring DSBs have also been achieved44. Here, we describe the optimization of the CRISPR-Cas system regarding the diversified development of Cas proteins, the optimization of Cas promoters, and the empowerment of sgRNAs with multiplexing capability (Table 1).

Table 1.

Optimization of the CRISPR-Cas system in plants

| Name | From | Function | Crop species | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas proteins | ||||

| St1Cas9 | Streptococcus thermophilus | Size is smaller; recognizes longer PAMs (“NNAGAA” or “NNGGAA”) | Arabidopsis | 45 |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | Size is smaller; recognizes longer PAMs (“NNGGGT” or “NNGAA”) | Arabidopsis; tobacco | 45,46 |

| SpCas9-VQR | Streptococcus pyogenes | Recognizes “NGA” PAM | Rice | 47 |

| SpCas9- VRER | Streptococcus pyogenes | Recognizes “NGCG” PAM | Rice | 47 |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | Acidaminococcus sp. BV3L6 (As); Francisellanovicida (Fn); Lachnospiraceae bacterium ND2006 (Lb) | Recognizes “TTTN” or “TTN” PAMs; targets DNA to introduce a 5′ overhang; guided by a shorter crRNA; exhibits little off-target activity | Arabidopsis; maize; rice; soybean; tobacco | 48–51 |

| Cas13a (C2c2) | Leptotrichiashahii | Targets single-stranded RNA with PFS of A, U, or C | Rice; tobacco | 52,53 |

| nCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | Cas9 nickase contains a mutation in either of the two nuclease domains of Cas9 protein. It induces SSBs | Arabidopsis; rice; tomato | 54–56 |

| dCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | Deficient Cas9 contains mutations in both nuclease domains of Cas9 protein. without cleavage activity. The dCas9-based regulator can be developed when fused with transcriptional activators or repressors | Arabidopsis; maize; rice; tobacco; wheat | 56–59 |

| Promoters | Preferential expression | Crop species | Refs. | |

| Cas promoters | ||||

| YAO | Tissues undergoing active cell division including the shoot apical and root meristem, embryo sac, embryo, endosperm, and pollen | Arabidopsis; citrus | 60,61 | |

| SPL | Sporogenous cells and microsporocytes | Arabidopsis | 62 | |

| EC1.1/EC1.2 | Egg cells and one-cell stage embryos | Arabidopsis | 63,64 | |

| ICU2 | Meristematic regions | Arabidopsis | 65 | |

| EF1α, hisH4 | Meristematic and reproductive tissues | Arabidopsis | 66 | |

| MGE | Meiosis stage | Arabidopsis | 67 | |

| DMC1 | Meiocytes | Arabidopsis; maize | 68,69 | |

| RPS5A | At all developmental stages | Arabidopsis | 70 | |

| Strategy | Crop species | Refs. | ||

| sgRNAs | ||||

| Assemble multiple sgRNA expression cassettes into CRISPR-Cas vector | Arabidopsis; maize; Populus; rice; tobacco; tomato | 71–75 | ||

| Produce numerous sgRNAs from a single polycistronic gene via the endogenous tRNA-processing system | Maize; potato; rice; tomato; wheat | 76–80 | ||

PAM protospacer adjacent motif, sgRNA single-guide RNA, CRISPR-Cas clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat-CRISPR-associated, tRNA transfer RNA, PFS protospacer flanking sequence, SSBs single-strand breaks, crRNA CRISPR RNA

Applications of CRISPR-Cas9 in fruit crops

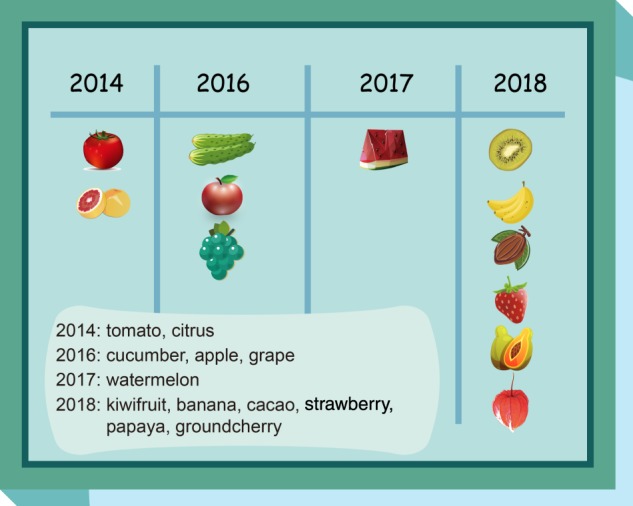

Duane Green has defined a fruit crop as a perennial, edible crop where the economic product is the true botanical fruit or derived from it81. Some plants, grown primarily as annuals, such as tomatoes, cucumbers, and melons, are also considered fruit crops82. Due to its easily achieved germplasm resources, simple diploid inheritance, efficient breeding, short growing period, ease of genetic transformation, and extensive research, tomato acts as a model for fruit biology1. Here, we summarize the applications of the CRISPR-Cas9 system in tomato and other fruit crops (Fig. 2 and Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Timeline of the first application of the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat-CRISPR-associated (CRISPR-Cas9) system in fruit crops

Table 2.

Current applications of CRISPR-Cas9 in fruit crops

| Crop species | Target genes | Target traits | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance to biotic stresses | |||

| Tomato | CP and Rep of virus | Resistance against tomato yellow leaf curl virus | 83 |

| Tomato | DCL2 | Susceptibility to potato virus X, tobacco mosaic virus, and tomato mosaic virus | 84,85 |

| Tomato | DMR6 | Resistance against downy mildew | 86 |

| Tomato | MLO1 | Resistance against powdery mildew | 87 |

| Tomato | PMR4 | Resistance against powdery mildew | 88 |

| Tomato | Solyc08g075770 | Susceptibility to Fusarium wilt disease | 89 |

| Tomato | MAPK3 | Susceptibility to gray mold disease | 90 |

| Tomato | JAZ2 | Resistance against bacterial speck disease | 91 |

| Banana | ORF region of virus | Resistance against banana streak virus | 92 |

| Cucumber | eIF4E | Resistance against cucumber vein yellowing virus, zucchini yellow mosaic virus, and papaya ring spot mosaic virus | 93 |

| Grape | MLO7 | Resistance against powdery mildew | 94 |

| Grape | WRKY52 | Resistance against gray mold disease | 95 |

| Cacao | NPR3 | Resistance against Phytophthora tropicalis | 96 |

| Papaya | alEPIC8 | Resistance against Phytophthora palmivora | 97 |

| Citrus | LOB1 promoter | Resistance against citrus canker | 98,99 |

| Apple | DIPM1, 2, 4 | Resistance against fire blight disease | 94 |

| Resistance to abiotic stresses | |||

| Tomato | BZR1 | Decrease in heat stress tolerance | 100 |

| Tomato | CBF1 | Decrease in chilling stress tolerance | 101 |

| Tomato | MAPK3 | Decrease in drought stress tolerance | 102 |

| Watermelon | ALS | Resistance against herbicide | 103 |

| Fruit quality improvement | |||

| Tomato | CLV3, lc | Fruits with increasing locule numbers | 104 |

| Tomato | PSY1 | Yellow-colored tomato | 105 |

| Tomato | MYB12 | Pink-colored tomato | 106 |

| Tomato | ANT2 (gene insertion) | Purple-colored tomato | 107 |

| Tomato | PL | Long-shelf life tomato | 108 |

| Tomato | ALC | Long-shelf life tomato | 109 |

| Tomato | MPK20 | Repression of genes controlling sugar metabolism | 110 |

| Tomato | ANT2 (gene insertion) | Increase in anthocyanin content | 107 |

| Tomato | GAD2, GAD3 | Increase in GABA content | 111 |

| Tomato | GABA-TP1, GABA-TP2, GABA-TP3, CAT9, SSADH | Increase in GABA content | 112 |

| Tomato | SGR1, LCY-E, Blc, LCY-B1, LCY-B2 | Increase in lycopene content | 113 |

| Tomato | ALMT9 | Decrease in malate content | 114 |

| Fruit crop domestication | |||

| Tomato | AGL6 | Production of parthenocarpic fruit | 115 |

| Tomato | IAA9 | Production of parthenocarpic fruit | 116 |

| Tomato | ARF7 | Production of parthenocarpic fruit | 117 |

| Tomato | MBP21 | Generation of “jointless” fruit stem | 118 |

| Tomato | GAI | Generation of dwarf tomato plants | 119 |

| Tomato | BOP1, BOP2, BOP3 | Early flowering with simplified inflorescences | 120 |

| Tomato | SP, SP5G, CLV3, WUS, GGP1 | Introduction of traits associated with morphology, flower and fruit production, and ascorbic acid synthesis | 121 |

| Tomato | SP, OVATE, MULT, FAS, CycB | Introduction of traits associated with morphology, flower number, tomato size and number, and lycopene synthesis | 122 |

| Tomato | SP5G | Generation of loss of day-length-sensitive tomato plants | 123 |

| Cucumber | WIP1 | Generation of gynoecious plant | 124 |

| Groundcherry | SP, SP5G, CLV1 | Introduction of traits associated with morphology, flower production, and fruit size | 125 |

| Kiwifruit | CEN4, CEN | Generation of a compact plant with rapid terminal flower and fruit development | 126 |

CRISPR-Cas clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat-CRISPR-associated, ORF open reading frame, GABA γ-aminobutyric acid

Current applications of CRISPR-Cas9 in tomato

In 2014, the CRISPR-Cas9 system was first applied in tomato. Argonaute 7 was knocked out resulting in wiry phenotypes; the first leaves of mutants had leaflets without petioles and subsequently formed leaves lacking laminae127. Since then, numerous publications on CRISPR-Cas9 application in tomato have been published. We classified these publications into the following four groups: resistance to biotic stresses, resistance to abiotic stresses, improvement of tomato fruit quality, and domestication of tomato.

Resistance to biotic stresses

Biotic stresses include viruses, bacteria, fungi, and insects, all of which can attack plants and cause damage128. CRISPR-Cas9 technology has been employed to obtain disease-resistant plants129 since its successful application for obtaining stable transgenic lines in 2013. Since then, CRISPR-Cas9 has been used against viral, fungal, and bacterial infection, which causes severe losses in tomato130,131.

For viruses, two strategies have been used. One consists of designing sgRNAs and targeting the virus genome directly through sequence complementation, and the other consists of modifying the tomato genes that confer antiviral characteristics. Tashkandi et al.83 used the CRISPR-Cas9 system to engineer tomato plants resistant to the tomato yellow leaf curl virus by targeting the coat protein and replicase loci of the genome. The transgenic tomato showed efficient viral interference and accumulated less viral genomic DNA than the wild-type (WT) plants. This kind of immunity remained active across multiple generations, indicating the utility of the CRISPR-Cas9 system for cultivating durable virus resistance plants. CRISPR-Cas9 technology has also been used to knock out crucial genes involved in resistance pathways, aiming to test whether these genes can confer immunity against viruses. Tomato Dicer-like 2 (DCL2) genes were targeted, and the dcl2 mutants displayed viral symptoms when infected by potato virus X, tobacco mosaic virus, and tomato mosaic virus, suggesting that DCL2 is involved in the defense mechanism against RNA viruses84,85.

Fungi are accountable for multiple diseases, including mildew, smut, rust, and rot, which can cause dramatic losses in crop yield and quality130. Downy and powdery mildews inflict severe economic losses in tomato. In Arabidopsis thaliana, downy mildew resistant 6 (DMR6), which belongs to the 2-oxoglutarate Fe(II)-dependent oxygenase superfamily, participates in salicylic acid homeostasis, and its overexpression results in enhanced susceptibility to downy mildew132. Researchers have used the CRISPR-Cas9 system to inactivate the DMR6 ortholog in tomato and found that dmr6 mutants showed disease resistance against various pathogens, including Pseudomonas syringae, Phytophthora capsica, and Xanthomonas spp., without significant detrimental effects86. Mildew resistant locus O 1 (Mlo1), which encodes a membrane-associated protein, confers susceptibility to the fungi causing powdery mildew disease. Nekrasov et al.87 generated the tomato loss-of-function mlo1 mutant using CRISPR-Cas9 technology and found that the mutant was fully resistant to the powdery mildew fungus Oidium neolycopersici. Notably, the authors segregated the transfer DNA (T-DNA) by selfing T0 transformants, and among the progeny, they identified mlo1 T-DNA-free mutants, which were regarded as transgene-free crops87. Powdery mildew resistance 4 (PMR4), which encodes a callose synthase, also leads to resistance against O. neolycopersici88. Another well-known tomato fungal pathosystem is Fusarium oxysporum131, which can cause Fusarium wilt disease. The yield of tomato fruit is negligible in highly infected plants. The Solyc08g075770 gene has been identified to function in Fusarium wilt tolerance, and CRISPR-Cas9 knockout transgenic plants exhibited disease susceptibility89. Botrytis cinerea is an airborne plant pathogen that causes gray mold disease, resulting in serious economic losses in both pre- and postharvest stages. Tomato is susceptible to postharvest infection by B. cinerea133. Mitogen-activated protein kinase 3 (MAPK3) has been shown to confer resistance to B. cinerea by using CRISPR-Cas9 technology90.

Due to undetectable asymptomatic infections and a lack of suitable agricultural chemicals, plant pathogenic bacteria are hard to control, and using genetic resistance against these pathogens is the most efficient strategy130. Pseudomonas syringae is the causative agent of the bacterial speck disease in tomato plants, negatively affecting their productivity and marketability. Because Jasmonatezim domain protein 2 (JAZ2) contributes to the defense against P. syringae in A. thaliana134, researchers used CRISPR-Cas9 to generate tomato dominant JAZ2 repressors lacking the C-terminal jasmonate associated (Jas) domain (JAZ2Δjas). These JAZ2Δjas repressors provide resistance to P. syringae, indicating that a CRISPR-Cas9-based strategy for fruit crop protection can be implemented in the field91.

Resistance to abiotic stresses

According to Charles Darwin's evolutionary theory, it is not the most intellectual or strongest species that survives, but the one that is able to adapt to and adjust best to the changing environment in which it finds itself135. Abiotic stresses such as drought, flooding, heat, and chilling, especially those under a climate change scenario, pose high risks to species, especially crops136. Traditional breeding techniques have greatly increased crop yield, but with the growing demand for food, new approaches are needed to further improve crop production, and CRISPR-Cas9 technology is the most promising137.

Brassinazole resistant 1 (BZR1) regulates brassinosteroid (BR) response and participates in BR-mediated developmental processes. Its ortholog in tomato also controls BR response. BZR1 is also involved in thermotolerance by regulating the Feronia (FER) genes, as verified by both CRISPR-bzr1- and BZR1-overexpressing lines100. Because tomato is a chilling-sensitive crop, its fruit quality is easily damaged due to chilling stress. Li et al.101 found that C-repeat binding factor 1 (CBF1) protects plants from cold injury, as the cbf1 mutant generated by CRISPR-Cas9 exhibited more severe chilling-injury symptoms with higher electrolyte leakage than WT plants. MAPK3, which participates in resistance against gray mold disease90, is also involved in tomato drought response by protecting cell membranes from oxidative damage102.

Improvement of tomato fruit quality

Fruit quality can be defined based on external and internal characteristics. The external quality factors are fruit size, color, and texture, all easily detected with the naked eye. Internal fruit quality attributes, including the levels of nutrients (such as sugar and vitamin) and bioactive compounds (such as lycopene, anthocyanin, and malate), need to be measured by instruments138.

In tomato fruit, the number of locules derived from the flower carpels has the greatest effect on tomato fruit size, contributing as much as 50% to the total variance in fruit enlargement. Locule number is controlled by multiple quantitative trait loci (QTL), a few of which have been identified139. Scientists at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory used CRISPR-Cas9 technology to rapidly generate larger tomato fruits by destructing the classical CLAVATA-WUSCHEL (CLV-WUS) stem cell circuit140. Eight sgRNAs were designed to target the promoter region of the CLV3 gene, and transgenic plants produced more organs and larger fruits than WT plants. The researchers also recreated a known fruit size QTL, locule number (lc) in tomato, generating fruits with increasing locule number104. Color and texture are also important aspects of consumer perception of fresh tomatoes141. Consumers from different areas have different color preferences. For instance, European and American consumers prefer red tomatoes, while in Asia, pink-colored tomatoes are more popular142,143. Researchers have successfully cultivated yellow105, pink106, and purple107 tomatoes by targeting phytoene synthase 1 (PSY1), MYB transcription factor 12 (MYB12), and Anthocyanin 2 (ANT2), respectively. Modifying texture characteristics for a prolonged shelf life has long been a challenge for breeders. The inactivation of ripening inhibitor (RIN) or DNA demethylase 2 (DML2) by CRISPR can lead to incomplete ripening fruits with long shelf life144,145. However, these fruits usually fail to develop full color, resulting in poor flavor and reduced nutritional value. Hence, obtaining fruits that exhibit good shelf life without affecting other quality aspects is crucial. Two research groups have reported successful harnessing of fruit softening by silencing pectate lyase (PL) and alcobaca (ALC) without reducing tomato organoleptic and nutritional quality108,109, suggesting that the CRISPR system might be an excellent tool for fruit crop improvement.

Regarding internal fruit quality, much effort has been made to increase the levels of nutrients and bioactive compounds. Carbohydrates and vitamins are vital nutrients because they provide energy. Several genes are involved in the synthesis and metabolism of sugar and carotenoids (provitamin A carotenoid can be absorbed and converted to vitamin A in the human body). For example, knocking out mitogen-activated protein kinase 20 (MPK20) disrupted the expression of several genes that control sugar metabolism at both the transcript and protein levels110. Bioactive compounds are defined as “extra nutritional constituents that typically occur in small quantities in foods” and usually play roles in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer146. Anthocyanin147, malate114, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)111, and lycopene113 are considered bioactive compounds, and CRISPR-Cas9 technology has been applied to produce anthocyanin-, GABA- and lycopene-enhanced tomato fruits by modulating the expression of key genes in their metabolic pathways107,111–113. The key gene that determines tomato malate content, aluminum-activated malate transporter 9 (ALMT9), has also been identified using CRISPR-Cas9114.

Domestication of tomato

Domestication of plants mostly affects the genes controlling plant morphology (seed size, dispersal mechanism, and plant architecture) and physiology (timing of germination, flowering, and ripening)148,149. To achieve the ideotype, classical breeding or modern “rewilding” crop breeding have introduced alleles from wild relatives into cultivated species. However, these techniques are time-consuming. An alternative strategy is direct manipulation of wild crops at the gene level to domesticate them de novo and harness their adaptation to adverse environments150. This de novo domestication has been substantially accelerated by the CRISPR-Cas9 technology.

Parthenocarpy, a fertilization-independent seedless fruit development, is regarded as a desirable agronomic trait in fruit crops: (i) it is advantageous for stable crop yield in fluctuating environments; (ii) it saves energy when separating the seeds from processed products for industrial purposes; and (iii) consumers prefer seedless over seeded fruits115–117. Klap et al.115 confirmed that a mutation in agamous-like 6 (AGL6) is responsible for parthenocarpic fruit production under heat stress conditions; because the mutant is of normal weight and shape, without homeotic changes, AGL6 is an attractive gene for parthenocarpy. Elevated gibberellin or auxin signaling can induce parthenocarpy without fertilization. The mutants produced by the knock out of indole-3-acetic acid inducible 9 (IAA9) and auxin response factor 7 (ARF7), both involved in the auxin signaling pathway, produced seedless fruits, which is a characteristic of parthenocarpic tomato116,117. The joint is a weak region of the stem that allows the fruit to drop from the plant. Wild species benefit from dropping fruit because this process contributes to seed dispersal, but because they use picking manipulators, farmers prefer to have fruit hanging on the plant. Breeders have been trying to obtain a mutant that eliminates the flower abscission zone (by which unfertilized flowers or ripe fruit are shed from the plant) and provides a “jointless” fruit stem151,152. Roldan et al.118 developed the MADS-box protein 21 (MBP21) loss-of-function mutant mbp21 exhibiting the jointless phenotype using CRISPR-Cas9 technology118. Fruits are easier to pick, and nutrients are transported over shorter distances from the roots to the leaves in dwarf plants compared with normal plants. Dwarf plants are also more likely to survive when exposed to strong winds. Heritable dwarf tomato plants have been generated by inactivating the gibberellic-acid insensitive (GAI) gene, and these plants can be useful in windy environments. However, the reduced fruit weight and seed number issues of these dwarf mutants need to be solved first119. Plant productivity depends on flowers, and inflorescence architecture determines flower production. CRISPR-Cas9 technology was used to silence the tomato blade-on-petiole (BOP) gene to test whether it has the same function as its homolog in A. thaliana (leaf complexity and organ abscission), which affects inflorescence architecture. Notably, the CRISPR-bop1/2/3 triple mutant flowered faster than the WT, but with extremely simplified inflorescences120.

Domestication of wild tomato species for commercial cultivation usually requires numerous phenotypes to be changed, including fruit setting and size, ripening synchrony, flowering and day-length sensitivity, and nutrient content121. Two research groups have recently devised a CRISPR-Cas9 technology that combines agronomically desirable traits with useful traits present in wild lines. One group targeted six loci of five genes critical for the productivity of present tomato lines, enabling the de novo domestication of wild Solanum pimpinellifolium whose morphology was altered, together with the size, number, and nutritional value of its fruits122. The other group introduced desirable traits into S. pimpinellifolium by editing coding sequences, cis-regulatory regions, or upstream ORFs of genes associated with morphology, flower and fruit production, and ascorbic acid synthesis121.

Sensitivity to day-length limits the geographical distribution of crops. Therefore, modification of the photoperiod response can help accelerate crop domestication processes. The loss of the day-length-sensitive tomato mutant produced by knocking out self-pruning 5G (SP5G) showed a quick burst of flower production that translated into an early fruit yield123.

Current applications of CRISPR-Cas9 in other fruit crops

The use of CRISPR-Cas9 technology is not limited to tomato. It has also been successfully applied to several other fruit crops, including strawberry153, banana154, grape155, apple156, watermelon157, and kiwifruit158. As a model organism, strawberry is often used for the functional analysis of specific genes. For instance, targeting R2R3 MYB transcription factor 10 (MYB10) leads to the generation of loss-of-coloration fruits159,160. Zhou et al.153 used CRISPR-Cas9 to target auxin response factor 8 (ARF8) and identified that arf8 homozygous mutants show faster seedling growth than WT plants. The tomato MADS-box gene 6 (TM6) is reported to play a predominant role in stamen development161. To characterize its function in strawberry, the CRISPR-Cas9 system was applied to an octoploid species, and the phenotypic analysis of tm6 mutants revealed severe defects in their anthers, indicating that TM6 played an essential role in flower development162. In addition, the CRISPR-Cas9 strategy was used to investigate the biological role of YUCCA 10 (YUC10) in auxin synthesis during strawberry fruit development. When YUC10 was knocked out, a significant reduction in free auxin was observed in yuc10 mutants163. In addition to the functional study in strawberry, an increasing number of researchers are focusing on CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing for improvement of other fruit crops. Here, we summarize the recent applications of CRISPR-Cas9 to other fruit crops considering the following aspects: resistance to biotic stresses, resistance to abiotic stresses, and domestication of fruit crops (Table 2).

Resistance to biotic stresses

In tropical and subtropical countries, the banana streak virus is a major challenge in banana breeding92. As mentioned above, one strategy for improving resistance to viruses is targeting their genomes with CRISPR-Cas9. Tripathi et al.92 used this system to inactivate the endogenous banana streak virus and found that 75% of the edited plants remained asymptomatic in comparison to the non-edited control. Plant RNA viruses require a host factor, such as the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), to maintain their life cycle. If the factor is inactivated, viral infectivity is disrupted. A virus-resistant cucumber mutant was developed using CRISPR-Cas9 to disrupt the function of eIF4E. As expected, the eif4e mutant exhibited immunity to cucumber vein yellowing virus, zucchini yellow mosaic virus, and papaya ring spot mosaic virus93. Fungal diseases can cause drastic losses in grapevine yield and grape berry quality. Two genes, mildew resistance locus O 7 (MLO7) and WRKY transcription factor 52 (WRKY52), are known to be involved in Erysiphe necator and B. cinerea resistance, respectively. Two research groups validated the functions of these genes using CRISPR-Cas9. Both loss-of-function mutants showed increased immunity94,95. This technology was also used in cacao and papaya to increase resistance against Phytophthora tropicalis and Phytophthora palmivora96,97. Citrus canker, caused by Xanthomonas citri, is a severe disease among most commercial citrus cultivars and is responsible for substantial economic losses worldwide. Two recent publications98,99 have reported the use of CRISPR-Cas9 for generating citrus plants resistant to citrus canker by targeting the promoter region of the lateral organ boundaries 1 (LOB1) gene in citrus; the mutated lines showed high degrees of resistance to X. citri infection. Similarly, in apple protoplasts, the genes encoding DspA/E-interacting proteins (DIPM1, DIPM2, and DIPM4) were knocked out to improve resistance against Erwinia amylovora94. Date palm is an important fruit crop in desert agriculture. Due to its large and complex genome and high frequency of single-nucleotide polymorphisms, the application of CRISPR-Cas9 is a challenging task, and therefore, few genetic improvement studies have been performed. However, Satter et al.164 presented a generalized stepwise and basic strategy for the theoretical implications of CRISPR-Cas9, addressing its potential applications in date palm.

Resistance to abiotic stresses

Field watermelons are severely threatened by weeds, but the use of herbicides also affects their growth. Therefore, herbicide-resistant watermelons should be obtained, which is difficult to achieve via traditional breeding. In recent years, CRISPR-mediated single-nucleotide conversion has been used to develop herbicide-resistant rice56. To introduce this new base-editing system in watermelon, Tian et al.103 selected acetolactate synthase (ALS), a gene in which point mutations confer a high level of herbicide resistance. The transgene-free als mutants and WT plants were treated with the herbicide tribenuron, and while all WT plants were severely damaged, the als mutants were not, suggesting the successful establishment of a CRISPR base-editing system and herbicide-resistant watermelons103.

Domestication of fruit crops

Gynoecious lines benefit cucumber breeding, as they allow earlier generation of hybrids, higher yield, and more concentrated fruit set; eliminate the requirement for artificial emasculation; and reduce the labor cost of crossing compared to monoecious lines. WIP domain-containing protein 1 (WIP1) inhibits carpel development in cucumber, and the loss-of-function wip1 mutant displays a gynoecious phenotype, bearing only female flowers in upper nodes124. Lemmon et al.125 domesticated an orphan crop, groundcherry, a wild Solanaceae grown in Central and South America. Using CRISPR-Cas9, three orthologs of tomato (self-pruning (SP), SP5G, and CLV1) that control plant architecture, flower production, and fruit size, respectively, were introduced into groundcherry, thereby improving these major productive characters in this crop. This successful application will accelerate the domestication of orphan crops by introducing known agronomic traits from distantly related model crops125. Kiwifruit is a recently domesticated fruit crop with large potential for improvement. By inactivating centroradialis 4 (CEN4) and CEN, which have been validated as repressors of flowering, the original climbing woody perennial was transformed into a compact plant with rapid terminal flower and fruit development126.

Concluding remarks

CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized crop breeding since its first application in 2013. The major breakthroughs were the generation of disease-resistant and environment-adaptive fruit crops, as well as improvement of fruit quality. Notably, the DNA-free delivery of preassembled CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins has been conducted in plant protoplasts of A. thaliana, rice, tobacco, lettuce, wheat, and potato165–168. Plants originating from this technology might be considered non-GM crops. This characterization would open the door for the development of fruit crops with superior phenotypes and allow their commercialization and marketing even in countries where GM crops are unacceptable169. In April 2016, the FDA indicated that the CRISPR-edited mushroom could enter the market without oversight, making it the first CRISPR-edited organism to receive such authorization from the US government16,170. In 2017, the FDA allowed the marketing of false flax, with enhanced omega-3 oil, and drought-tolerant soybean, clearly indicating that CRISPR-edited plants can be cultivated and sold free from regulation17 and thereby providing great confidence to research focusing on the application of CRISPR to fruit crops.

However, the growth of CRISPR-edited crops faces sociopolitical challenges, including public acceptance and government regulation171. Although transgene-free organisms edited by CRISPR-Cas9 are not currently regulated in the US, whether to govern the use of CRISPR technologies is still being discussed in China and Japan172. According to the decision of Europe’s highest court earlier in 2018, gene-edited crops should be subject to the same stringent regulations that govern conventional GM organisms, which is a major setback for proponents, including many scientists173. With further advances in CRISPR technology and the establishment of an evaluation system, more countries might be willing to foster an optimistic and inclusive attitude toward CRISPR-edited crops. As researchers, in addition to further investigating CRISPR technology to ensure maximum benefit while minimizing risks, we need to be concerned with public acceptance. Most importantly, the basic aspects of this technology need to be explained sufficiently well to facilitate rational public discourse, increasing public confidence in the safety and advantages of CRISPR-edited crops. Governments might then express a laissez faire attitude after gaining strong public trust.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFD0400901) and National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (31622050 and 31672208) to H.Z. T.W. was supported by a fellowship from the Chinese Scholarship Council (201706350174).

Author contributions

T.W. and H.Z. planned the manuscript outline. T.W. wrote the draft and created the figures and tables. H.Z. and H.Z. revised and proofread the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Giovannoni J, Nguyen C, Ampofo B, Zhong S, Fei Z. The epigenome and transcriptional dynamics of fruit ripening. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2017;68:61–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042916-040906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramdath DD, Isaacs RL, Teelucksingh S, Wolever TM. Glycaemic index of selected staples commonly eaten in the Caribbean and the effects of boiling v. crushing. Br. J. Nutr. 2004;91:971–977. doi: 10.1079/BJN20041125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vayalil PK. Date fruits (Phoenix dactylifera Linn): an emerging medicinal food. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2012;52:249–271. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2010.499824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh B, Singh JP, Kaur A, Singh N. Bioactive compounds in banana and their associated health benefits— a review. Food Chem. 2016;206:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karkute SG, Singh AK, Gupta OP, Singh PM, Singh B. CRISPR/Cas9 mediated genome engineering for improvement of horticultural Crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:01635. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hickey JM, et al. Genomic prediction unifies animal and plant breeding programs to form platforms for biological discovery. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:1297–1303. doi: 10.1038/ng.3920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer RS, Purugganan MD. Evolution of crop species: genetics of domestication and diversification. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013;14:840–852. doi: 10.1038/nrg3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tester M, Langridge P. Breeding technologies to increase crop production in a Changing world. Science. 2010;327:818–822. doi: 10.1126/science.1183700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bigliardi B, Galati F. Innovation trends in the food industry: the case of functional foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013;31:118–129. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2013.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parmar N, et al. Genetic engineering strategies for biotic and abiotic stress tolerance and quality enhancement in horticultural crops: a comprehensive review. 3 Biotech. 2017;7:239. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-0870-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bawa AS, Anilakumar KR. Genetically modified foods: safety, risks and public concerns—a review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013;50:1035–1046. doi: 10.1007/s13197-012-0899-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gould, F. et al. in Genetically Engineered Crops: Experiences and Prospects (eds Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources) Ch. 6 (National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2016). [PubMed]

- 13.Millstone E, Stirling A, Glover D. Regulating genetic engineering the limits and politics of knowledge. Issues Sci. Technol. 2015;31:23–26. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falck-Zepeda J, et al. Estimates and implications of the costs of compliance with biosafety regulations in developing countries. GM Crops Food. 2012;3:52–59. doi: 10.4161/gmcr.18727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jefferson DJ, Graff GD, Chi-Ham CL, Bennett AB. The emergence of agbiogenerics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:819–823. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J, Kim J. Bypassing GMO regulations with CRISPR gene editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:1014–1015. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waltz E. With a free pass, CRISPR-edited plants reach market in record time. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36:6–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt0118-6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaidi SS, Mukhtar MS, Mansoor S. Genome editing: targeting susceptibility genes for plant disease resistance. Trends Biotechnol. 2018;36:898–906. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sternberg SH, Richter H, Charpentier E, Qimron U. Adaptation in CRISPR-Cas systems. Mol. Cell. 2016;61:797–808. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishino Y, Shinagawa H, Makino K, Amemura M, Nakata A. Nucleotide sequence of the iap gene, responsible for alkaline phosphatase isozyme conversion in Escherichia coli, and identification of the gene product. J. Bacteriol. 1987;169:5429–5433. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.12.5429-5433.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jansen R, Embden JDAV, Gaastra W, Schouls LM. Identification of genes that are associated with DNA repeats in prokaryotes. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;43:1565–1575. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolotin A, Ouinquis B, Sorokin A, Ehrlich SD. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindrome repeats (CRISPRs) have spacers of extrachromosomal origin. Microbiology. 2005;151:2551–2561. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mojica FJM, Díez-Villaseñor CS, García-Martínez JS, Soria E. Intervening sequences of regularly spaced prokaryotic repeats derive from foreign genetic elements. J. Mol. Evol. 2005;60:174–182. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pourcel C, Salvignol G, Vergnaud G. CRISPR elements in Yersinia pestis acquire new repeats by preferential uptake of bacteriophage DNA, and provide additional tools for evolutionary studies. Microbiology. 2005;151:653–663. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27437-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shan Q, et al. Targeted genome modification of crop plants using a CRISPR-Cas system. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:686–688. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cong L, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaboli S, Babazada H. CRISPR mediated genome engineering and its application in industry. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2018;26:81–92. doi: 10.21775/cimb.026.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hille F, Charpentier E. CRISPR-Cas: biology, mechanisms and relevance. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Ser. B. 2016;371:20150496. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nam KH, et al. Cas5d protein processes pre-crRNA and assembles into a cascade-like interference complex in subtype I-C/Dvulg CRISPR-Cas system. Structure. 2012;20:1574–1584. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rouillon C, et al. Structure of the CRISPR interference complex CSM reveals key similarities with cascade. Mol. Cell. 2013;52:124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gasiunas G, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V. Cas9-crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:E2579–E2586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208507109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doudna JA, Charpentier E. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science. 2014;346:1258096. doi: 10.1126/science.1258096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amitai G, Sorek R. CRISPR–Cas adaptation: insights into the mechanism of action. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;14:67–76. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2015.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang H, La Russa M, Qi LS. CRISPR/Cas9 in genome editing and beyond. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2016;85:227–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yin K, Gao C, Qiu J. Progress and prospects in plant genome editing. Nat. Plants. 2017;3:17107. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2017.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marraffini, L. A. in Streptococcus pyogenes: Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations [Internet] (eds Ferretti, J. J., Stevens, D. L. & Fischetti, V. A.) Ch. 11 (University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, 2016). [PubMed]

- 37.Liu X, Xie C, Si H, Yang J. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in plants. Methods. 2017;121–122:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donohoue PD, Barrangou R, May AP. Advances in industrial biotechnology using CRISPR-Cas systems. Trends Biotechnol. 2018;36:134–146. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang W, Wersch S, Tong M, Li X. TIR-NB-LRR immune receptor SOC3 pairs with truncated TIR-NB protein CHS1 or TN2 to monitor the homeostasis of E3 ligase SAUL1. New Phytol. 2018;221:2054–2066. doi: 10.1111/nph.15534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mao Y, et al. Manipulating plant RNA-silencing pathways to improve the gene editing efficiency of CRISPR/Cas9 systems. Genome Biol. 2018;19:149. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1529-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li R, Fu D, Zhu B, Luo Y, Zhu H. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of lncRNA1459 alters tomato fruit ripening. Plant J. 2018;94:513–524. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang H, et al. CRISPR/cas9, a novel genomic tool to knock down microRNA in vitro and in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:22312. doi: 10.1038/srep22312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seth K, Harish Current status of potential applications of repurposed Cas9 for structural and functional genomics of plants. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016;480:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.10.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hess GT, Tycko J, Yao D, Bassik MC. Methods and applications of CRISPR-mediated base editing in eukaryotic genomes. Mol. Cell. 2017;68:26–43. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steinert J, Schiml S, Fauser F, Puchta H. Highly efficient heritable plant genome engineering using Cas9 orthologues from Streptococcus thermophilus and Staphylococcus aureus. Plant J. 2015;84:1295–1305. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaya H, Mikami M, Endo A, Endo M, Toki S. Highly specific targeted mutagenesis in plants using Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:26871. doi: 10.1038/srep26871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu X, et al. Expanding the range of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in rice. Mol. Plant. 2016;9:943–945. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee K, et al. Activities and specificities of CRISPR/Cas9 and Cas12a nucleases for targeted mutagenesis in maize. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019;17:362–372. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tang X, et al. A CRISPR–Cpf1 system for efficient genome editing and transcriptional repression in plants. Nat. Plants. 2017;3:17018. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2017.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim H, et al. CRISPR/Cpf1-mediated DNA-free plant genome editing. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14406. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Endo A, Masafumi M, Kaya H, Toki S. Efficient targeted mutagenesis of rice and tobacco genomes using Cpf1 from Francisella novicida. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:38169. doi: 10.1038/srep38169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aman R, et al. RNA virus interference via CRISPR/Cas13a system in plants. Genome Biol. 2018;19:1. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1381-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abudayyeh OO, et al. RNA targeting with CRISPR-Cas13. Nature. 2017;550:280–284. doi: 10.1038/nature24049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mikami M, Toki S, Endo M. Precision targeted mutagenesis via Cas9 paired nickases in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016;57:1058–1068. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcw049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fauser F, Schiml S, Puchta H. Both CRISPR/Cas-based nucleases and nickases can be used efficiently for genome engineering in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2014;79:348–359. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shimatani Z, et al. Targeted base editing in rice and tomato using a CRISPR-Cas9 cytidine deaminase fusion. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017;35:441–443. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zong Y, et al. Precise base editing in rice, wheat and maize with a Cas9-cytidine deaminase fusion. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017;35:438–440. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang F, et al. EIN2 mediates direct regulation of histone acetylation in the ethylene response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:10274–10279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707937114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Piatek A, et al. RNA-guided transcriptional regulationin planta via synthetic dCas9-based transcription factors. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2015;13:578–589. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang F, LeBlanc C, Irish VF, Jacob Y. Rapid and efficient CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in citrus using the YAO promoter. Plant Cell Rep. 2017;36:1883–1887. doi: 10.1007/s00299-017-2202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yan L, et al. High-efficiency genome editing in Arabidopsis using YAO promoter-driven CRISPR/Cas9 system. Mol. Plant. 2015;8:1820–1823. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mao Y, et al. Development of germ-line-specific CRISPR-Cas9 systems to improve the production of heritable gene modifications in Arabidopsis. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016;14:519–532. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wolter F, Klemm J, Puchta H. Efficientin planta gene targeting in Arabidopsis using egg cell-specific expression of the Cas9 nuclease of Staphylococcus aureus. Plant J. 2018;94:735–746. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang Z, et al. Egg cell-specific promoter-controlled CRISPR/Cas9 efficiently generates homozygous mutants for multiple target genes in Arabidopsis in a single generation. Genome Biol. 2015;16:144. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0715-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hyun Y, et al. Site-directed mutagenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana using dividing tissue-targeted RGEN of the CRISPR/Cas system to generate heritable null alleles. Planta. 2015;241:271–284. doi: 10.1007/s00425-014-2180-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Osakabe Y, et al. Optimization of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing to modify abiotic stress responses in plants. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:26685. doi: 10.1038/srep26685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eid A, Ali Z, Mahfouz MM. High efficiency of targeted mutagenesis in Arabidopsis via meiotic promoter-driven expression of Cas9 endonuclease. Plant Cell Rep. 2016;35:1555–1558. doi: 10.1007/s00299-016-2000-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xu P, Su H, Chen W, Lu P. The application of a meiocyte-specific CRISPR/Cas9 (MSC) system and a suicide-MSC system in generating inheritable and stable mutations in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:01007. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Feng C, et al. High-efficiency genome editing using admc1 promoter-controlled CRISPR/Cas9 system in maize. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018;16:1848–1857. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tsutsui H, Higashiyama T. pKAMA-ITACHI vectors for highly efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017;58:w191. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcx098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yu T, et al. Genome-wide identification of long non-coding RNA targets of the tomato MADS box transcription factor RIN and function analysis. Ann. Bot. 2019;123:469–482. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcy178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Char SN, et al. An Agrobacterium-delivered CRISPR/Cas9 system for high-frequency targeted mutagenesis in maize. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017;15:257–268. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ma X, et al. A robust CRISPR/Cas9 system for convenient, high-efficiency multiplex genome editing in monocot and dicot plants. Mol. Plant. 2015;8:1274–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fan D, et al. Efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis in populus in the first generation. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:12217. doi: 10.1038/srep12217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gao J, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis in Nicotiana tabacum. Plant Mol. Biol. 2015;87:99–110. doi: 10.1007/s11103-014-0263-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hashimoto R, Ueta R, Abe C, Osakabe Y, Osakabe K. Efficient multiplex genome editing induces precise, and self-ligated type mutations in tomato plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:00916. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nakayasu M, et al. Generation of α-solanine-free hairy roots of potato by CRISPR/Cas9 mediated genome editing of the St16DOX gene. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018;131:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li C, et al. Expanded base editing in rice and wheat using a Cas9-adenosine deaminase fusion. Genome Biol. 2018;19:59. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1443-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Qi W, et al. High-efficiency CRISPR/Cas9 multiplex gene editing using the glycine tRNA-processing system-based strategy in maize. BMC Biotechnol. 2016;16:58. doi: 10.1186/s12896-016-0289-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xie K, Minkenberg B, Yang Y. Boosting CRISPR/Cas9 multiplex editing capability with the endogenous tRNA-processing system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:3570–3575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420294112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rieger, M. in Introduction to Fruit Crops (ed. Rieger, M.) Ch. 1 (Food Products Press, Boca Raton, 2006).

- 82.Miller AJ, Gross BL. From forest to field: perennial fruit crop domestication. Am. J. Bot. 2011;98:1389–1414. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1000522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tashkandi M, Ali Z, Aljedaani F, Shami A, Mahfouz MM. Engineering resistance against Tomato yellow leaf curl virus via the CRISPR/Cas9 system in tomato. Plant Signal. Behav. 2018;13:e1525996. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2018.1525996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang Z, et al. A novel DCL2-dependent miRNA pathway in tomato affects susceptibility to RNA viruses. Gene. Dev. 2018;32:1155–1160. doi: 10.1101/gad.313601.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang T, et al. Tomato DCL2b is required for the biosynthesis of 22-nt small RNAs, the resulting secondary siRNAs, and the host defense against ToMV. Hortic. Res. 2018;5:62. doi: 10.1038/s41438-018-0073-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Thomazella, D., Brail, Q., Dahlbeck, D. & Staskawicz, B. CRISPR-Cas9 mediated mutagenesis of a DMR6 ortholog in tomato confers broad-spectrum disease resistance. BioRxiv10.1101/064824 (2016).

- 87.Nekrasov V, et al. Rapid generation of a transgene-free powdery mildew resistant tomato by genome deletion. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:482–486. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00578-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Koseoglou, E. Wageningen University, http://edepot.wur.nl/422311 (2017).

- 89.Prihatna C, Barbetti MJ, Barker SJ. A novel tomato Fusarium Wilt tolerance gene. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:1226. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang S, et al. Knockout of SlMAPK3 reduced disease resistance to Botrytis cinerea in tomato plants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018;66:8949–8956. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b02191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ortigosa A, Gimenez-Ibanez S, Leonhardt N, Solano R. Design of a bacterial speck resistant tomato by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing ofSlJAZ2. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019;17:665–673. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tripathi JN, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 editing of endogenous banana streak virus in the B genome of Musa spp. overcomes a major challenge in banana breeding. Commun. Biol. 2019;2:46. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0288-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chandrasekaran J, et al. Development of broad virus resistance in non-transgenic cucumber using CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016;17:1140–1153. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Malnoy M, et al. DNA-free genetically edited grapevine and apple protoplast using CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1904. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wang X, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated efficient targeted mutagenesis in grape in the first generation. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018;16:844–855. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fister AS, Landherr L, Maximova SN, Guiltinan MJ. Transient expression of CRISPR/Cas9 machinery targeting TcNPR3 enhances defense response in Theobroma cacao. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:268. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gumtow R, Wu D, Uchida J, Tian M. A Phytophthora palmivora extracellular cystatin-like protease inhibitor targets papain to contribute to virulence on papaya. Mol. Plant Microbe. 2018;31:363–373. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-06-17-0131-FI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jia H, Orbovic V, Jones JB, Wang N. Modification of the PthA4 effector binding elements in type I CsLOB1 promoter using Cas9/sgRNA to produce transgenic Duncan grapefruit alleviating XccΔpthA4:dCsLOB1.3 infection. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016;14:1291–1301. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Peng A, et al. Engineering canker-resistant plants through CRISPR/Cas9-targeted editing of the susceptibility gene CsLOB1 promoter in citrus. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017;15:1509–1519. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yin Y, et al. BZR1 transcription factor regulates heat stress tolerance through FERONIA receptor-like kinase-mediated reactive oxygen species signaling in tomato. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018;59:2239–2254. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcy146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Li R, et al. Reduction of tomato-plant chilling tolerance by CRISPR-Cas9-mediated SlCBF1 mutagenesis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018;66:9042–9051. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b02177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wang L, et al. Reduced drought tolerance by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated SlMAPK3 mutagenesis in tomato plants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017;65:8674–8682. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b02745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tian S, et al. Engineering herbicide-resistant watermelon variety through CRISPR/Cas9-mediated base-editing. Plant Cell Rep. 2018;37:1353–1356. doi: 10.1007/s00299-018-2299-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rodríguez-Leal D, Lemmon ZH, Man J, Bartlett ME, Lippman ZB. Engineering quantitative trait variation for crop improvement by genome editing. Cell. 2017;171:470–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Filler Hayut S, Melamed Bessudo C, Levy AA. Targeted recombination between homologous chromosomes for precise breeding in tomato. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15605. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Deng L, et al. Efficient generation of pink-fruited tomatoes using CRISPR/Cas9 system. J. Genet. Genom. 2018;45:51–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Čermák T, Baltes NJ, Čegan R, Zhang Y, Voytas DF. High-frequency, precise modification of the tomato genome. Genome Biol. 2015;16:232. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0796-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Uluisik S, et al. Erratum: Corrigendum: genetic improvement of tomato by targeted control of fruit softening. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:1072. doi: 10.1038/nbt1016-1072d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yu Q, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-induced targeted mutagenesis and gene replacement to generate long-shelf life tomato lines. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:11874. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12262-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chen L, et al. Evidence for a specific and critical role of mitogen-activated protein kinase 20 in uni-to-binucleate transition of microgametogenesis in tomato. New Phytol. 2018;219:176–194. doi: 10.1111/nph.15150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nonaka S, Arai C, Takayama M, Matsukura C, Ezura H. Efficient increase of ɣ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) content in tomato fruits by targeted mutagenesis. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:7057. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06400-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Li R, et al. Multiplexed CRISPR/Cas9-mediated metabolic engineering of γ-aminobutyric acid levels in Solanum lycopersicum. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018;16:415–427. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Li X, et al. Lycopene is enriched in tomato fruit by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated multiplex genome editing. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:559. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ye J, et al. An inDel in the promoter of Al-activated malate transporter9 selected during tomato domestication determines fruit malate contents and Aluminum tolerance. Plant Cell. 2017;29:2249–2268. doi: 10.1105/tpc.17.00211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Klap C, et al. Tomato facultative parthenocarpy results from SlAGAMOUS-LIKE 6 loss of function. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017;15:634–647. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ueta R, et al. Rapid breeding of parthenocarpic tomato plants using CRISPR/Cas9. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:507. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00501-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hu J, Israeli A, Ori N, Sun T. The interaction between DELLA and ARF/IAA mediates crosstalk between gibberellin and auxin signaling to control fruit initiation in tomato. Plant Cell. 2018;30:1710–1728. doi: 10.1105/tpc.18.00363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Roldan MVG, et al. Natural and induced loss of function mutations in SlMBP21 MADS-box gene led to jointless-2 phenotype in tomato. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:4402. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04556-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tomlinson L, et al. Using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in tomato to create a gibberellin-responsive dominant dwarf DELLA allele. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019;17:132–140. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Xu C, Park SJ, Van Eck J, Lippman ZB. Control of inflorescence architecture in tomato by BTB/POZ transcriptional regulators. Gene Dev. 2016;30:2048–2061. doi: 10.1101/gad.288415.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Li T, et al. Domestication of wild tomato is accelerated by genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36:1160–1163. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zsögön A, et al. De novo domestication of wild tomato using genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36:1211–1216. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Soyk S, et al. Variation in the flowering gene SELF PRUNING 5G promotes day-neutrality and early yield in tomato. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:162–168. doi: 10.1038/ng.3733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hu B, et al. Engineering non-transgenic gynoecious cucumber using an improved transformation protocol and optimized CRISPR/Cas9 system. Mol. Plant. 2017;10:1575–1578. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lemmon ZH, et al. Rapid improvement of domestication traits in an orphan crop by genome editing. Nat. Plants. 2018;4:766–770. doi: 10.1038/s41477-018-0259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Varkonyi‐Gasic Erika, Wang Tianchi, Voogd Charlotte, Jeon Subin, Drummond Revel S. M., Gleave Andrew P., Allan Andrew C. Mutagenesis of kiwifruit CENTRORADIALIS ‐like genes transforms a climbing woody perennial with long juvenility and axillary flowering into a compact plant with rapid terminal flowering. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2018;17(5):869–880. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Brooks C, Nekrasov V, Lippman ZB, Van Eck J. Efficient gene editing in tomato in the first generation using the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated9 system. Plant Physiol. 2014;166:1292–1297. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.247577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Langner T, Kamoun S, Belhaj K. CRISPR crops: plant genome editing toward disease resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2018;56:479–512. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080417-050158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Arora L, Narula A. Gene editing and crop improvement using CRISPR-Cas9 system. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:1932. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Borrelli VMG, Brambilla V, Rogowsky P, Marocco A, Lanubile A. The enhancement of plant disease resistance using CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:1245. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.R C, HS A. Resistance-gene-mediated defense responses against biotic stresses in the crop model plant tomato. J. Plant Pathol. Microbiol. 2017;08:404. doi: 10.4172/2157-7471.1000404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Zeilmaker T, et al. Downy mildew resistant 6 and DMR6-like oxygenaSE 1 are partially redundant but distinct suppressors of immunity in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2015;81:210–222. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Yu W, Zhao R, Sheng J, Shen L. SlERF2 is associated with methyl jasmonate-mediated defense response against Botrytis cinerea in tomato fruit. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018;66:9923–9932. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b03971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Gimenez-Ibanez S, et al. JAZ2 controls stomata dynamics during bacterial invasion. New Phytol. 2017;213:1378–1392. doi: 10.1111/nph.14354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Darwin, C. (ed.). On the Origin of Species 6th edn (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2009).

- 136.Mushtaq M, et al. CRISPR/Cas approach: a new way of looking at plant–abiotic interactions. J. Plant Physiol. 2018;224–225:156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Haque E, et al. Application of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technology for the improvement of crops cultivated in tropical climates: recent progress, prospects, and challenges. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:617. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Satpute MR, Jagdale SM. Color, size, volume, shape and texture feature extraction techniques for fruits: a review. Int. Res. J. Engin. Technol. 2016;4:703–708. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Li H, et al. Tomato transcription factor SlWUS plays an important role in tomato flower and locule development. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:457. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Ma X, et al. Different roles for RNA silencing and RNA processing components in virus recovery and virus-induced gene silencing in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2015;66:919–932. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Oltman AE, Jervis SM, Drake MA. Consumer attitudes and preferences for fresh market tomatoes. J. Food Sci. 2014;79:S2091–S2097. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Lin T, et al. Genomic analyses provide insights into the history of tomato breeding. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:1220–1226. doi: 10.1038/ng.3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Ballester AR, et al. Biochemical and molecular analysis of pink tomatoes: deregulated expression of the gene encoding transcription factor SlMYB12 leads to pink tomato fruit color. Plant Physiol. 2009;152:71–84. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.147322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Lang Z, et al. Critical roles of DNA demethylation in the activation of ripening-induced genes and inhibition of ripening-repressed genes in tomato fruit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E4511–E4519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705233114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Ito Y, Nishizawa-Yokoi A, Endo M, Mikami M, Toki S. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of the RIN locus that regulates tomato fruit ripening. Biochem. Bioph. Res. Commun. 2015;467:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.09.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Kris-Etherton PM, et al. Bioactive compounds in foods: their role in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. Am. J. Med. 2002;113:71–88. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00995-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Meng X, et al. Physiological changes in fruit ripening caused by overexpression of tomato SlAN2, an R2R3-MYB factor. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2015;89:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Zeder MA. The domestication of animals. J. Anthropol. Res. 2012;68:161–190. doi: 10.3998/jar.0521004.0068.201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Zeder, M. A. in Documenting Domestication: New Genetic And Archaeological Paradigms 1st edn (eds Zeder, M. A., Bradley, D. G., Emshwiller, E. & B. D. Smith) Ch. 13 (University of California Press, Berkeley, 2006).

- 150.Zsögön A, Cermak T, Voytas D, Peres LEP. Genome editing as a tool to achieve the crop ideotype and de novo domestication of wild relatives: case study in tomato. Plant Sci. 2017;256:120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Soyk S, et al. Bypassing negative epistasis on yield in tomato imposed by a domestication gene. Cell. 2017;169:1142–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Ledford H. Fixing the tomato: CRISPR edits correct plant-breeding snafu. Nature. 2017;545:394–395. doi: 10.1038/nature.2017.22018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Zhou J, Wang G, Liu Z. Efficient genome editing of wild strawberry genes, vector development and validation. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018;16:1868–1877. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Kaur N, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated efficient editing in phytoene desaturase (PDS) demonstrates precise manipulation in banana cv. Rasthali genome. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2018;18:89–99. doi: 10.1007/s10142-017-0577-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Nakajima I, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis in grape. PLos ONE. 2017;12:e177966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Nishitani C, et al. Efficient genome editing in apple using a CRISPR/Cas9 system. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:31481. doi: 10.1038/srep31481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Tian S, et al. Efficient CRISPR/Cas9-based gene knockout in watermelon. Plant Cell Rep. 2017;36:399–406. doi: 10.1007/s00299-016-2089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Wang Z, et al. Optimized paired-sgRNA/Cas9 cloning and expression cassette triggers high-efficiency multiplex genome editing in kiwifruit. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018;16:1424–1433. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Tang T, et al. Development and validation of an effective CRISPR/Cas9 vector for efficiently isolating positive transformants and transgene-free mutants in a wide range of plant species. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:1533. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Xing S, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-introduced single and multiple mutagenesis in strawberry. J. Genet Genom. 2018;45:685–687. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2018.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Roque E, et al. Functional specialization of duplicated AP3-like genes in Medicago truncatula. Plant J. 2013;73:663–675. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Martín-Pizarro C, Triviño JC, Posé D. Functional analysis of the TM6 MADS-box gene in the octoploid strawberry by CRISPR/Cas9-directed mutagenesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2019;70:885–895. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Feng J, et al. Reporter gene expression reveals precise auxin synthesis sites during fruit and root development in wild strawberry. J. Exp. Bot. 2019;70:563–574. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Sattar MN, et al. CRISPR/Cas9: a practical approach in date palm genome editing. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1469. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Zhang Y, et al. Efficient and transgene-free genome editing in wheat through transient expression of CRISPR/Cas9 DNA or RNA. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12617. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Woo JW, et al. DNA-free genome editing in plants with preassembled CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:1162–1164. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Liang Z, et al. Efficient DNA-free genome editing of bread wheat using CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14261. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]